Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Roots of Yoga PDF

Загружено:

sanoopsrajОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Roots of Yoga PDF

Загружено:

sanoopsrajАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Penguin Press

Date: 18/11/2016

Designer: Freelance / Jim

Roots of Yoga

‘Yoga is to be known through yoga. Yoga arises Production Controller:

ISBN: 9780241253045

from yoga. One who is vigilant by means of

yoga delights in yoga for a long time.’ Spine Width 25.5mm

Estimated

Confirmed

Yoga is hugely popular around the world today, yet until now little

has been known of its roots. This book collects, for the first time, Format B

core teachings of yoga in their original form, translated and edited 129mm x 198mm

by two of the world’s foremost scholars of the subject. It includes

a wide range of texts from different schools of yoga, languages Paper

and eras: among others, key passages from the early Upanisads .

– –

and the Mahabharata, and from the Tantric, Buddhist and Jaina Print

traditions, with many pieces in scholarly translation for the first time. CMYK

Other (see below)

Covering yoga’s varying definitions across systems, its most important

practices, such as posture, breath control, sensory withdrawal and

Finishes

meditation, as well as models of the esoteric and physical bodies,

Roots of Yoga is a unique and essential source of knowledge. Pantone 1505C

Gloss Varnish

(Spot Matt Page Two)

Translated and edited wit h an introduction by

J AME S MAL L I N SO N an d M A R K S I N G L E TO N

Proofing Method

Digital plus wet proofs

Digital only

No further proof required.

Archive files supplied

P E N G U I N C L A S S I C S P E N G U I N C L A S S I C S Additional Instructions:

(Including spec changes)

P E N G U I N

– asana

Cover: tapkara – (the ascetic’s

posture). From a c.1830 illustrated

Penguin Literature

– –©

manuscript of the Jogapradipaka

The British Library Board

II S

SBBN

UK £10.99

N 978-0-241-25304-5

978-0-241-25304-5

Roots of Yoga

99 00 00 00 00

C L A S S I C S

99 77 88 00 22 44 11 22 55 33 00 44 55 Translated and wit h an introduction by

JAM ES M AL L I NSON and M A R K S I N G L E TON

9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_COV.indd 1 21/11/2016 14:23

Roots of Yoga

Translated and Edited

with an Introduction by

james mallinson and mark singleton

p e ngu i n b o o k s

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd iii 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

PENGUIN CLASSICS

U K | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This edition first published in Penguin Classics 2017

001

Introductions, original translations and editorial material

© James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, 2017

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translators and editors has been asserted

All rights reserved

Set in 10.25/12.25 pt Adobe Sabon

Typeset by Jouve (U K), Milton Keynes

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

isbn: 978– 0– 241– 25304– 5

www.greenpenguin.co.uk

Penguin Random House is committed to a

sustainable future for our business, our readers

and our planet book is made from Forest

Stewardship Council® certified paper.

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd iv 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

Contents

Note on the Reference System and Diacritics vii

Introduction ix

Timeline of Important Texts xxxix

ROOTS OF YOGA

1. Yoga 3

2. Preliminaries 46

3. Posture 86

4. Breath-control 127

5. The Yogic Body 171

6. Yogic Seals 228

7. Mantra 259

8. Withdrawal, Fixation and Meditation 283

9. Samādhi 323

10. Yogic Powers 359

11. Liberation 395

Glossary 437

Primary Sources 443

Secondary Literature 455

Notes 473

Acknowledgements 507

Index 511

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd v 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

Introduction1

Over the last three decades there has been an enormous increase

in the popularity of yoga around the world. The United Nations’

recent declaration of an International Day of Yoga 2 is symbolic of

yoga’s truly globalized status today. Along with this globaliza-

tion, however, has come metamorphosis: yoga has adapted to

social and cultural conditions often far removed from those of its

birthplace, and in many regions has taken on a life of its own,

independent of its Indian roots. The global diffusion of yoga

began at least a century and a half ago, since which time yoga has

continued to be refracted through many new cultural prisms, such

as New Age religion, psychology, sports science, biomedicine, and

so on. 3

In spite of yoga’s now global popularity (or perhaps, rather,

because of it), a clear understanding of its historical contexts in

South Asia, and the range of practices that it includes, is often lack-

ing. This is at least partly due to limited access to textual material.4

A small canon of texts, which includes the Bhagavadgītā, Patañ-

jali’s Yogasūtras, the Hathapradīpikā and some Upanisads, may

˙ ˙

be studied within yoga teacher-training programmes, but by and

large the wider textual sources are little known outside specialized

scholarship. Along with the virtual hegemony of a small number of

posture-oriented systems in the recent global transmission of yoga,

this has reinforced a relatively narrow and monochromatic vision

of what yoga is and does, especially when viewed against the wide

spectrum of practices presented in pre-modern texts.

Of course, texts are not reflective of the totality of yoga’s

development – they merely provide windows on to particular trad-

itions at particular times – and an absence of evidence for certain

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd ix 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

x i nt roduc t ion

practices within texts is not evidence of their absence within yoga

as a whole. 5 Conversely, the appearance of new practices in texts

is itself often an indication of older innovations. Despite these

limitations, however, texts remain a unique and dependable source

of knowledge about yoga at particular moments in history, in con-

trast to often unverifiable retrospective self-accounts of particular

lineages. In addition to texts, material sources, particularly sculp-

ture and painting from the second millennium ce, provide

invaluable data for the reconstruction of yoga’s history. While we

have not addressed such sources directly here, they have informed

our analyses. Examples of our work with such sources can be

found in Diamond 2013.

In some respects this book resembles a traditional Sanskrit

nibandha (scholarly compilation) in that it gathers together a wide

variety of texts on a single topic.6 Unlike a nibandha, however,

our approach does not have a sectarian religious orientation, and

it will, we hope, be somewhat more accessible as a result. The

material is drawn from more than a hundred texts, dating from

about 1000 bce to the nineteenth century, many of which are not

well known. Although most of the passages translated here are from

Sanskrit texts, there is also material from Tibetan, Arabic, Per-

sian, Bengali, Tamil, Pali, Kashmiri, Old Marathi, Avadhi and

Braj Bhasha (late-medieval precursors of Hindi) and English

sources. This chronological and linguistic range reveals patterns

and continuities that contribute to a better understanding of

yoga’s development within and across traditions (for example,

between earlier Sanskrit sources and later vernacular or

non-Indian texts which draw on them). Where possible, we have

used the earliest available textual occurrence of a particular pas-

sage, rather than a later duplication. For this reason, perhaps

better known but derivative texts, such as the later Yoga Upa-

nisads,7 are passed over in favour of the earlier texts from which

˙

they borrow. By and large we have not included material which is

incidental to the mainstream of yoga theory and practice in South

Asia, nor do we draw on non-textual sources popularly considered

to be fundamental to yoga’s history, but which have been discred-

ited by scholarship.8 Indeed, this collection benefits enormously

from advances in historical and philological research in yoga

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd x 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

i nt roduc t ion xi

traditions over the past three decades (see ‘Yoga Scholarship’

below, p. xxii).

The yoga whose roots we are identifying is that which prevailed

in India on the eve of colonialism, i.e. the late eighteenth century.

Although certainly not without its variations and exceptions, by

this time there is a pervasive, trans-sectarian consensus throughout

India as to what constitutes yoga in practice. One of the reasons for

this is the rise to predominance of the techniques of hathayoga,

˙

which held a virtual hegemony across a wide spectrum of

yoga-practising religious traditions, including the Brahmanical

traditions, in the pre-colonial period.9 The texts included in this

collection reflect this historical development. As well as delimiting

what would otherwise be an unmanageable amount of material,

focusing on yoga as it was most commonly understood helps to

reflect the actual practices of a majority of traditions in which yoga

was undertaken. Such a focus can also help shed light on the imme-

diate predecessors of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century yogis

who helped disseminate yoga around the world.

The material represented here is largely practical in nature, not

philosophical. In general, we do not include passages on meta-

physics unless they are directly related to practice (e.g. meditation

on the elements (tattvas)). Although traditional yoga rarely, if

ever, occurs outside of particular religious and doctrinal contexts,

these contexts vary considerably, while yoga itself retains essen-

tial theoretical and practical commonalities.10 We therefore focus

mainly on the practice of yoga and not on the philosophical sys-

tems that may underpin this practice in its specific sectarian

settings. In addition, a distinction needs to be drawn between yoga

as practice, as found across a wide range of Indian traditions, and

Yoga as a doctrinal or philosophical system rooted in traditions of

exegesis (i.e. textual interpretation) that developed from the Pātañ-

jalayogaśāstra. Notwithstanding the popular notion that the

Pātañjalayogaśāstra is the fundamental text of yoga, and fully rec-

ognizing its enormous impact on practical formulations of yoga

throughout history (in particular hathayoga, with which it is some-

˙

times identified in texts),11 it is in fact a partisan text, representing

an early Brahmanical appropriation of extra-Vedic, Śramana tech-

˙

niques of yoga, such as those of early Buddhism (on which, see

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd xi 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

xii i nt roduc t ion

below p. xiii). Its long exegetical tradition is not one of practice but

of philosophy. Although this exegesis is vital to understanding the

development of metaphysical speculation in South Asia, particu-

larly in orthodox contexts, it is not our focus here, in that it does

not significantly contribute to a history of yoga practices. Those

interested in the philosophical traditions associated with the

Pātañjalayogaśāstra should consult Philipp Maas’s forthcoming

sourcebook of yoga’s ‘classical dualist philosophy’.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that this is not a manual of

yoga practice. It is a work of scholarship documenting a wide

range of yoga methods, a few of which may cause injury or illness,

and some of which may even lead to physical and/or cognitive

‘death’, if practised successfully. The reader undertakes the prac-

tices described in this book entirely at his or her own risk.

H I S TOR IC A L OV E RV I E W

Yoga in Vedic-era Sources

Prior to about 500 bce there is very little evidence within South

Asian textual or archaeological sources that points to the exis-

tence of systematic, psychophysical techniques of the type which

the word ‘yoga’ subsequently came to denote. Passages in the old-

est Sanskrit text, the fifteenth- to twelfth-century bce Rg Veda

˙

(the earliest of the four ‘Vedas’, the textual foundation of ortho-

dox, ‘Vedic’ Hinduism) indicate the use of visionary meditation

and its famous hymn to a long-haired sage (10.136) suggests a

mystical ascetic tradition similar to those of later yogis.12 The

somewhat later Atharva Veda (c. 1000 bce),13 in its description of

the Vrātya, who, like the long-haired sage, exists on the fringe of

mainstream Vedic society, mentions practices which may be fore-

runners of later yogic techniques of posture and breath-retention

(on the latter, see 4.1), and the Jaiminīya Upanisad Brāhmana

˙ ˙

(c. 800– 600 bce) teaches mantra-repetition, together with control

of the breath. But it is entirely speculative to claim, as several

popular writers on yoga have done,14 that the Vedic corpus pro-

vides any evidence of systematic yoga practice.

7TH_9780241253045_RootsOfYoga_PRE.indd xii 12/3/16 1:14:27 PM

Вам также может понравиться

- Five Element Acupuncture Theory and Clinical Applications - TCM TheoryДокумент6 страницFive Element Acupuncture Theory and Clinical Applications - TCM Theorysanoopsraj100% (1)

- Unit 3Документ16 страницUnit 3sanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 Psychophysics: Threshold, Signal Detection Theory: StructureДокумент10 страницUnit 2 Psychophysics: Threshold, Signal Detection Theory: StructuresanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- Unit 4Документ16 страницUnit 4sanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- Day 2 - Past Regression Therapy TA Script WRKSHP PDFДокумент1 страницаDay 2 - Past Regression Therapy TA Script WRKSHP PDFsanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- What Is Psychotherapy - 15 Techniques and Exercises (+PDF)Документ22 страницыWhat Is Psychotherapy - 15 Techniques and Exercises (+PDF)sanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- Kandhar Sashti Kavasam MEANINGДокумент8 страницKandhar Sashti Kavasam MEANINGsanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- 20 Important Spiritual InstructionsДокумент8 страниц20 Important Spiritual InstructionssanoopsrajОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 2015 Us CalendarДокумент28 страниц2015 Us Calendarintimate2me100% (1)

- Hanuman Mantra To Combat FearДокумент3 страницыHanuman Mantra To Combat FearVashikaran.OrgОценок пока нет

- Fairs and Festivals Part1Документ162 страницыFairs and Festivals Part1Ananya PanditОценок пока нет

- ब्रह्मान्ड पुराण संस्कृत eng bk2 ch7Документ40 страницब्रह्मान्ड पुराण संस्कृत eng bk2 ch7Mohit VaishОценок пока нет

- Cherthala Pooram: Sree Karthyayani Devi TempleДокумент3 страницыCherthala Pooram: Sree Karthyayani Devi TempleHarisankar Karthika HariharanОценок пока нет

- Swami Vivekananda and Pavhari BabaДокумент6 страницSwami Vivekananda and Pavhari BabaSwami Vedatitananda100% (2)

- Varnada LagnaДокумент12 страницVarnada Lagnaanusha100% (2)

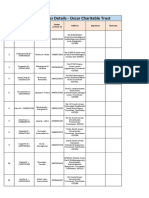

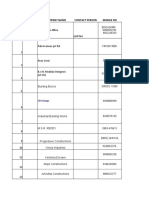

- DDU GKY Candidates Details - Oscar Charitable TrustДокумент3 страницыDDU GKY Candidates Details - Oscar Charitable TrustRaghul TОценок пока нет

- Learning Activity Sheets Arts 8, Quarter 3, Week 1 Southeast Asian ArtsДокумент10 страницLearning Activity Sheets Arts 8, Quarter 3, Week 1 Southeast Asian ArtshepidedapadoОценок пока нет

- Brahmo SamjДокумент19 страницBrahmo SamjVANSHIKA CHAUDHARYОценок пока нет

- Indian National Movement (History) Course OutlineДокумент5 страницIndian National Movement (History) Course OutlineMallela Manideep GoudОценок пока нет

- For Free Downloads Join 1Документ10 страницFor Free Downloads Join 1Sreedhar KonduruОценок пока нет

- Veerateeswarar Temple, ThiruvirkudiДокумент4 страницыVeerateeswarar Temple, ThiruvirkudiChristopher ServantОценок пока нет

- DXT - Oeaton: Case Study: Bharat BhavanДокумент21 страницаDXT - Oeaton: Case Study: Bharat BhavanKishore KumarОценок пока нет

- Speech-Head GirlДокумент1 страницаSpeech-Head GirlsssОценок пока нет

- Gheranda Samhita Chapter 7Документ2 страницыGheranda Samhita Chapter 7Poovitha100% (3)

- Bhagavad GIta PARTE 1 PDFДокумент134 страницыBhagavad GIta PARTE 1 PDFLuis Tovar CarrilloОценок пока нет

- MANDYAДокумент128 страницMANDYAGagan GowdaОценок пока нет

- Holiday List 2023 Word File - 231103 - 185520Документ2 страницыHoliday List 2023 Word File - 231103 - 185520Manju JaswalОценок пока нет

- Notre Dame Academy, MungerДокумент6 страницNotre Dame Academy, MungerPerween KhatoonОценок пока нет

- DLLE Payment Request LetterДокумент6 страницDLLE Payment Request LetterRishabh BohraОценок пока нет

- Ghaisas Eknathi Bhagwat Ch-12Документ49 страницGhaisas Eknathi Bhagwat Ch-12streamtОценок пока нет

- Candi of Indonesia: Hindu-Buddha or "Hindu-Buddhist Period" BetweenДокумент26 страницCandi of Indonesia: Hindu-Buddha or "Hindu-Buddhist Period" BetweenCraita BusuiocОценок пока нет

- EthnographyofAncientIndia PDFДокумент195 страницEthnographyofAncientIndia PDFanon_179299510Оценок пока нет

- Traveling Agent For Mail of EventДокумент30 страницTraveling Agent For Mail of EventShakshi SharmaОценок пока нет

- Kapol Vidyanidhi International School (Icse) : Annual Syllabus For 2021-2022 (Std. Ix)Документ4 страницыKapol Vidyanidhi International School (Icse) : Annual Syllabus For 2021-2022 (Std. Ix)Dheer MehtaОценок пока нет

- Bhagavad Gita Test ch.13Документ1 страницаBhagavad Gita Test ch.13johnyboyОценок пока нет

- Vedic Corpus DR Vinayak Rajat BhatДокумент34 страницыVedic Corpus DR Vinayak Rajat Bhatsrirajgirish7Оценок пока нет

- Samba ShivaДокумент3 страницыSamba Shivavaidehi emaniОценок пока нет

- Rjy XLДокумент65 страницRjy XLDIKSHA VERMAОценок пока нет