Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Settlement 301: 49 Ibid., P. 301, Memorial of November 22,1865. 50 Ibid., P. 304, Court Decision of November 22,1865

Загружено:

nandi_scr0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

39 просмотров1 страницаThe Japanese court reluctantly agreed to allow the ports of Hyogo and Osaka to be opened for foreign trade in accordance with the London Protocol, though there was disagreement about this in 1867. As the Bakufu had not met all of the Western demands, it agreed to pay the entire Shimonoseki indemnity and negotiate a revision of tariffs. In January 1866, negotiations began regarding currency, navigation aids, and removing restrictions on trade. An agreement was finally signed in June 1866 establishing a general 5% customs duty on imports and exports and specifying rates for some items.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

26

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThe Japanese court reluctantly agreed to allow the ports of Hyogo and Osaka to be opened for foreign trade in accordance with the London Protocol, though there was disagreement about this in 1867. As the Bakufu had not met all of the Western demands, it agreed to pay the entire Shimonoseki indemnity and negotiate a revision of tariffs. In January 1866, negotiations began regarding currency, navigation aids, and removing restrictions on trade. An agreement was finally signed in June 1866 establishing a general 5% customs duty on imports and exports and specifying rates for some items.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

39 просмотров1 страницаSettlement 301: 49 Ibid., P. 301, Memorial of November 22,1865. 50 Ibid., P. 304, Court Decision of November 22,1865

Загружено:

nandi_scrThe Japanese court reluctantly agreed to allow the ports of Hyogo and Osaka to be opened for foreign trade in accordance with the London Protocol, though there was disagreement about this in 1867. As the Bakufu had not met all of the Western demands, it agreed to pay the entire Shimonoseki indemnity and negotiate a revision of tariffs. In January 1866, negotiations began regarding currency, navigation aids, and removing restrictions on trade. An agreement was finally signed in June 1866 establishing a general 5% customs duty on imports and exports and specifying rates for some items.

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 1

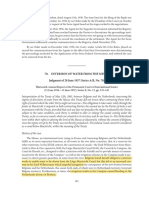

SETTLEMENT 301

the bakufu given countenance to such a policy publicly in its dealings

with the court. Backing it up, the senior bakufu officials in Kyoto,

including Keiki, formally warned the court in a joint memorial that if

Japan provoked hostilities over this issue, "we should have not the

least hope of victory. "49

Faced with this unanimity, the court gave way. The emperor gave

his consent to the treaties, commenting that "unsatisfactory provi-

sions" in them needed to be revised.'0 He refused to authorize any

action regarding Hyogo and Osaka, though the bakufu, in communi-

cating with the foreign representatives, assumed this to mean that they

could be opened in accordance with the London Protocol. There was

to be further disagreement on this subject in 1867, when the court

became aware of what had been said. No statement was made about

tariffs, which had at no time been mentioned in the Japanese discus-

sions. The fact reflects a characteristic of the treaty port system that

was common to both China and Japan at this stage: Whereas the West

saw the system in terms of commercial advantage, both Chinese and

Japanese were preoccupied with the political disabilities it imposed on

them. They made economic concessions almost without thought.

This is borne out by the bakufu's subsequent behavior. Because it

had not met all the West's demands, it accepted the necessity of

paying the whole of the Shimonoseki indemnity. Moreover, it agreed

to negotiate a revision of tariffs. When talks about this began in Janu-

ary 1866, Parkes, who took the lead in the matter on behalf of the

powers, promptly expanded them to include arrangements concerning

currency, which was still causing difficulties; the establishment of

navigation aids, such as lighthouses; and the removal of all those

restrictions on trade to which reference had been made in the London

Protocol. He refused to contemplate any further delay in the indem-

nity payments until a satisfactory agreement had been reached on

these points. This was not to be until June 25, 1866, when a conven-

tion was at last signed by Britain, France, Holland, and the United

States, to come into force at Yokohama on July 1 and a month later at

Hakodate and Nagasaki.

The convention was in effect an addendum to the 1858 treaties,

spelling out free-trade doctrine as it applied to Japanese conditions.

Goods imported into and exported from Japan were to be subject to

customs dues calculated at a general level of 5 percent, either in the

form of specified amounts or ad valorem. Some items, such as books,

49 Ibid., p. 301, memorial of November 22,1865.

50 Ibid., p. 304, court decision of November 22,1865.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Вам также может понравиться

- Settlement 299: Policy, Chaps. 8-14. Lshii, Zoteimeijilshin, Chaps. 5 and 6, Also Discusses This at LengthДокумент1 страницаSettlement 299: Policy, Chaps. 8-14. Lshii, Zoteimeijilshin, Chaps. 5 and 6, Also Discusses This at Lengthnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- History of ChinaДокумент3 страницыHistory of ChinaRaghvendra YadavОценок пока нет

- 3oo The Foreign Threat: Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008Документ1 страница3oo The Foreign Threat: Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- The Internal and External Factors Responsible For The Collapse of The Tokugawa ShogunateДокумент7 страницThe Internal and External Factors Responsible For The Collapse of The Tokugawa ShogunateAnushka DattaОценок пока нет

- Imperialism in China and BeyondДокумент11 страницImperialism in China and BeyondMarlon Joshua PacturanОценок пока нет

- The Internal and External Factors Responsible For The Collapse of The Tokugawa ShogunateДокумент4 страницыThe Internal and External Factors Responsible For The Collapse of The Tokugawa ShogunateSoumya Srijan Dasgupta96% (27)

- Maritime DelimitationДокумент7 страницMaritime DelimitationmrudulaОценок пока нет

- 12 Hongkong LJ 179Документ25 страниц12 Hongkong LJ 179kanye zhangОценок пока нет

- DMA Tokugawa Shogunate - 2Документ3 страницыDMA Tokugawa Shogunate - 2Priyam MishraОценок пока нет

- The Harris TreatyДокумент2 страницыThe Harris Treatyapi-272248497100% (1)

- The Japan House Tax Case, 1899-1905: Leases in Perpetuity and The Myth of International EqualityДокумент22 страницыThe Japan House Tax Case, 1899-1905: Leases in Perpetuity and The Myth of International EqualityĐào LêОценок пока нет

- 13 Brit YBIntl L68Документ9 страниц13 Brit YBIntl L68Yossuda RaicharoenОценок пока нет

- Japanese Civil CodeДокумент1 страницаJapanese Civil CodeEmina HoottОценок пока нет

- RingkasanДокумент24 страницыRingkasanvincentius paduatamaОценок пока нет

- Termination of Contracts in Hong KongДокумент23 страницыTermination of Contracts in Hong KongalexОценок пока нет

- Harris TreatyДокумент4 страницыHarris Treatyapi-191653274Оценок пока нет

- Assignment of JapamДокумент8 страницAssignment of JapamSajal S.KumarОценок пока нет

- Postwar Economic and Political ProblemsДокумент5 страницPostwar Economic and Political ProblemsMaslino JustinОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Maritime DelimiationДокумент25 страницJurnal Maritime DelimiationAdrie Yusuf PurwantoОценок пока нет

- Full Download Legal Environment 5th Edition Test Bank Jeffrey F Beatty PDF Full ChapterДокумент35 страницFull Download Legal Environment 5th Edition Test Bank Jeffrey F Beatty PDF Full Chaptermichaelcollinsxmsfpytneg100% (17)

- Idea of HistoryДокумент6 страницIdea of HistoryMihir KeshariОценок пока нет

- Convention of Constantinople - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент2 страницыConvention of Constantinople - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediabaknedicemОценок пока нет

- Opinion - 25 Years On Reflecting On Hong Kongs HandoverДокумент3 страницыOpinion - 25 Years On Reflecting On Hong Kongs HandoverCaio CesarОценок пока нет

- Accordo Austro Turco 1909Документ5 страницAccordo Austro Turco 1909Sao MaoОценок пока нет

- Kanae TAIJUDO - The Takeshima DisputeДокумент33 страницыKanae TAIJUDO - The Takeshima DisputeHenk CobraОценок пока нет

- Sykes Picot AgreementДокумент4 страницыSykes Picot AgreementanushkakelkarОценок пока нет

- Case DigestsДокумент20 страницCase DigestsDenise Michaela YapОценок пока нет

- Western Policy in ChinaДокумент22 страницыWestern Policy in ChinaMila InkayzОценок пока нет

- Centrifugal ForcesДокумент9 страницCentrifugal ForcesRohit SantoshОценок пока нет

- PIL Project Sem 4Документ12 страницPIL Project Sem 4Alan JohnОценок пока нет

- Transfer of Sovereignty Over Hong KongДокумент20 страницTransfer of Sovereignty Over Hong KongDavid SilverОценок пока нет

- British Foreign Policy in SiamДокумент25 страницBritish Foreign Policy in SiamNURDAMIA DURAR BINTI GAMZURRYОценок пока нет

- Ambatielos CaseДокумент2 страницыAmbatielos Caseb2spiritОценок пока нет

- 6 Pac Rim LPoly J683Документ118 страниц6 Pac Rim LPoly J683Jazz JuniorОценок пока нет

- Kuril Islands Dispute: Case Study of Russian - Japanese Relations.Документ17 страницKuril Islands Dispute: Case Study of Russian - Japanese Relations.Jason M BootheОценок пока нет

- Cases - Treaties FullДокумент20 страницCases - Treaties FullLouem GarceniegoОценок пока нет

- Akbayan vs. AquinoДокумент2 страницыAkbayan vs. AquinoJinx JinxОценок пока нет

- 3-4-ILI - ADR Paper-III - Int. Comm. Arb. - History - Development and Meaning Etc.-1Документ111 страниц3-4-ILI - ADR Paper-III - Int. Comm. Arb. - History - Development and Meaning Etc.-1himanshi kaushikОценок пока нет

- History of Derivatives MarketsДокумент1 страницаHistory of Derivatives MarketsRajan NandolaОценок пока нет

- Worksheet 01 - Origin of HK Question (Video) - TeacherДокумент3 страницыWorksheet 01 - Origin of HK Question (Video) - Teacherwongellie912Оценок пока нет

- Akbayan vs. AquinoДокумент2 страницыAkbayan vs. AquinoEspino Emmanuel0% (1)

- Akbayan Vs Aquino DigestДокумент2 страницыAkbayan Vs Aquino DigestWarry SolivenОценок пока нет

- RevisionДокумент7 страницRevisionCynthia HuaiОценок пока нет

- Full Download Test Bank For Microeconomics and Behavior 10th Edition Robert Frank PDF Full ChapterДокумент34 страницыFull Download Test Bank For Microeconomics and Behavior 10th Edition Robert Frank PDF Full Chaptercymule.nenia.szj6100% (17)

- Sykes Picot AgreementДокумент2 страницыSykes Picot AgreementBoban MarjanovicОценок пока нет

- The Geneva Convention of 1864 and The Brussels Conference of 1874Документ10 страницThe Geneva Convention of 1864 and The Brussels Conference of 1874dauzivert6Оценок пока нет

- The European Coal and Steel Community: WWW - OvidiuioandumitruДокумент14 страницThe European Coal and Steel Community: WWW - OvidiuioandumitruLorena TudorascuОценок пока нет

- International Court of JusticeДокумент6 страницInternational Court of JusticeJP DCОценок пока нет

- Case Book of International LawДокумент49 страницCase Book of International LawMoniruzzaman Juror67% (3)

- Bowring TreatyДокумент2 страницыBowring TreatyRohitnanda Sharma ThongratabamОценок пока нет

- General Principles of International LawДокумент33 страницыGeneral Principles of International LawRaghav Pandey100% (1)

- Akbayan v. AquinoДокумент2 страницыAkbayan v. AquinoJonimar Coloma QueroОценок пока нет

- Diversion of Water From The Meus (Pcij Summary)Документ10 страницDiversion of Water From The Meus (Pcij Summary)JenicaОценок пока нет

- 3-4-ILI - ADR Paper-III - Int. Comm. Arb. - History - Development and Meaning Etc.Документ105 страниц3-4-ILI - ADR Paper-III - Int. Comm. Arb. - History - Development and Meaning Etc.himanshi kaushikОценок пока нет

- Slides For Seeing and Solving World Problems With Mundane AstrologyДокумент28 страницSlides For Seeing and Solving World Problems With Mundane AstrologyEhab Atari Abu-ZeidОценок пока нет

- E.U. Law - Course 2 - The Sources of E.U LawДокумент22 страницыE.U. Law - Course 2 - The Sources of E.U LawElena Raluca RadulescuОценок пока нет

- Vol I The Map of Europe by Treaty Showing The Various Political and Territorial Changes Which Have Taken Place Since The General Peace of 1814 by Hertslet, Edward, Sir, 1824-1902Документ856 страницVol I The Map of Europe by Treaty Showing The Various Political and Territorial Changes Which Have Taken Place Since The General Peace of 1814 by Hertslet, Edward, Sir, 1824-1902pba100% (1)

- Io6 Japan in The Early Nineteenth Century: Rangaku, Did Not Extend To His Grandson Seikei (1817-59), Who WasДокумент3 страницыIo6 Japan in The Early Nineteenth Century: Rangaku, Did Not Extend To His Grandson Seikei (1817-59), Who Wasnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Image of The Western World 99Документ3 страницыImage of The Western World 99nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- 2 PDFДокумент2 страницы2 PDFnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- 298 The Foreign Threat: Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008Документ1 страница298 The Foreign Threat: Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- 2 PDFДокумент2 страницы2 PDFnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH3Документ1 страницаAH3nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- The General AssemblyДокумент1 страницаThe General Assemblynandi_scrОценок пока нет

- ABFДокумент1 страницаABFnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Powers DeniedДокумент1 страницаPowers Deniednandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Direction of The CounsellДокумент1 страницаDirection of The Counsellnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Documents of American HistoryДокумент1 страницаDocuments of American Historynandi_scrОценок пока нет

- One Yr YouthДокумент1 страницаOne Yr Youthnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH2Документ1 страницаAH2nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- 74 1Документ1 страница74 1nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH1Документ1 страницаAH1nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH1Документ1 страницаAH1nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH1Документ1 страницаAH1nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Powers DeniedДокумент1 страницаPowers Deniednandi_scrОценок пока нет

- DgsДокумент1 страницаDgsnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH3Документ1 страницаAH3nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- ABFДокумент1 страницаABFnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- AH2Документ1 страницаAH2nandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Bandra WorliДокумент2 страницыBandra Worlinandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Pile - Point of FixityДокумент10 страницPile - Point of FixityJahid Jahidul Islam Khan89% (9)

- A Comparative Study of Various Clauses of New IS 1893 (Part 1) :2016 and Old IS 1893 (Part 1) :2002Документ8 страницA Comparative Study of Various Clauses of New IS 1893 (Part 1) :2016 and Old IS 1893 (Part 1) :2002basabi12Оценок пока нет

- Artcraft PDFДокумент1 страницаArtcraft PDFnandi_scrОценок пока нет

- ElastoДокумент4 страницыElastonandi_scrОценок пока нет

- Monetary Policy: The Economic ProblemДокумент23 страницыMonetary Policy: The Economic ProblemDOODGE CHIDHAKWAОценок пока нет

- Mine Mate 2018Документ2 страницыMine Mate 2018rudresh svОценок пока нет

- Office-2ndEd LSC SB 26597Документ33 страницыOffice-2ndEd LSC SB 26597Desi LovegoodОценок пока нет

- Oregon Revenue ForecastДокумент23 страницыOregon Revenue ForecastSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneОценок пока нет

- Fin 200 Time Value of Money Tutorial 2 Solutions 2021.Документ2 страницыFin 200 Time Value of Money Tutorial 2 Solutions 2021.Mtshidi Kewagamang100% (2)

- Dharavi'S Recycling IndustryДокумент16 страницDharavi'S Recycling IndustryGanesh AlagirisamyОценок пока нет

- Porsche IPO On The Table To Push "Electrification and Digitalization Offensive"Документ2 страницыPorsche IPO On The Table To Push "Electrification and Digitalization Offensive"Maria MeranoОценок пока нет

- Micro Perspective of Tourism and Hospitality (Thc1)Документ11 страницMicro Perspective of Tourism and Hospitality (Thc1)Jomharey Agotana BalisiОценок пока нет

- How To Transfer Vehicle From One State To AnotherДокумент24 страницыHow To Transfer Vehicle From One State To AnothernpsОценок пока нет

- De Cuong Tieng Anh 7 - HK2 - UYENДокумент4 страницыDe Cuong Tieng Anh 7 - HK2 - UYENUyên TạОценок пока нет

- Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceДокумент12 страницDate Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceSiddhant A. KhankalОценок пока нет

- Bola Pelang IДокумент9 страницBola Pelang Iivan rasyidОценок пока нет

- Indonesia-Korea Medical Roadshow 2023 (Seminar Program With Speaker Info)Документ2 страницыIndonesia-Korea Medical Roadshow 2023 (Seminar Program With Speaker Info)Eko BudiarsoОценок пока нет

- Information About Indian Companies: ChennaiДокумент1 страницаInformation About Indian Companies: Chennailingeshsaikumar030Оценок пока нет

- Exercises 2 - SolutionsДокумент3 страницыExercises 2 - SolutionsbatuhanОценок пока нет

- Operations Management 12th Edition Stevenson Test BankДокумент25 страницOperations Management 12th Edition Stevenson Test BankMrDustinAllisongmer100% (42)

- Block Level Development PlanningДокумент20 страницBlock Level Development Planningyaswanth chowdaryОценок пока нет

- Intercompany Sales Problem Solving Exercises (Test Bank)Документ2 страницыIntercompany Sales Problem Solving Exercises (Test Bank)Kristine Esplana ToraldeОценок пока нет

- Banking, Customer Satisfaction & IDBI Bank Awareness: HereДокумент15 страницBanking, Customer Satisfaction & IDBI Bank Awareness: HereAyush GadeОценок пока нет

- Practical QuestionsДокумент5 страницPractical QuestionsBui Thi Lan Anh (FGW HCM)Оценок пока нет

- TRC Ar2018 en 01Документ228 страницTRC Ar2018 en 01Santhiya MogenОценок пока нет

- Sri Saraswathy A/P Sandra Raju (4181002751) TEST 2 PFS3363 12034Документ2 страницыSri Saraswathy A/P Sandra Raju (4181002751) TEST 2 PFS3363 12034SriSaraswathy100% (2)

- Banking and FinanceДокумент74 страницыBanking and FinancekimmheanОценок пока нет

- Contemporary WorldДокумент35 страницContemporary WorldtabiОценок пока нет

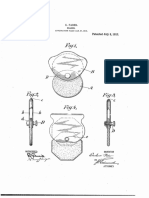

- 1,067,012. Patented July 8, 1913,: E, FaberДокумент4 страницы1,067,012. Patented July 8, 1913,: E, FaberGalo YambayОценок пока нет

- LHXXXXXXXXXXXX24Документ2 страницыLHXXXXXXXXXXXX24Dhananjay RambhatlaОценок пока нет

- Salaryslip Nov. 2022Документ1 страницаSalaryslip Nov. 2022Raj DelhiОценок пока нет

- List of Countries Forecast 2025 - DeagelДокумент3 страницыList of Countries Forecast 2025 - DeagelAbanoub100% (4)

- Basic Economic Problems and The Philippine Socioeconomic Development in The 21st CenturyДокумент3 страницыBasic Economic Problems and The Philippine Socioeconomic Development in The 21st CenturyRobert BalinoОценок пока нет

- Ac312, Assignment 1, Dela CruzДокумент4 страницыAc312, Assignment 1, Dela CruzChelsea Dela CruzОценок пока нет