Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Developing Effective Communication Skills: Strategies For Career Success

Загружено:

DANDY RADITYAОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Developing Effective Communication Skills: Strategies For Career Success

Загружено:

DANDY RADITYAАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Strategies for Career Success

Developing Effective Communication Skills

A practicing oncologist likely uses just Cohn suggests creating a setting in

about every medium to communicate. which “listening can be

They talk on the phone, send e-mail accommodating.” For example,

messages, converse one-on-one, don’t have a conversation when one

participate in meetings, and give verbal person is standing and one person is

and written orders. And they sitting—make sure your eyes are at the

communicate with many audiences— same level. Eliminate physical barriers,

patients and their families, referring such as a desk, between you and the

physicians, and office staff. other party. Acknowledge the speaker

with your own body language: lean

But are you communicating forward slightly and maintain eye

effectively? How do you handle contact. Avoid crossing your arms,

differing or challenging perspectives? which conveys a guarded stance and

Are you hesitant to disagree with may suggest arrogance, dislike, or

others, especially those in authority? disagreement.

Do you find meetings are a waste of

time? What impression does your When someone is speaking, put a

communication style make on the premium on “being present.” Take a

members of your group? deep breath (or drink some water to

keep from speaking) and create a

Be an Active Listener mental and emotional connection

The starting place for effective between you and the speaker. “This is

communication is effective listening. not a time for multitasking, but to

“Active listening is listening with all of devote all the time to that one person,”

one’s Cohn advises. “If you are thinking

senses,” says physician communication about the next thing you

expert have to do or, worse, the next thing you

Kenneth H. plan to say, you aren’t actively

Cohn, MD, listening.”

MBA, FACS.

“It’s listening Suspending judgment is also part of

with one’s active listening, according to Cohn.

eyes as well Encourage the speaker to fully express

as one’s herself or himself—free of interruption,

years. Only criticism, or direction. Show your

8% of interest by inviting the speaker to say

more with expressions such as “Can

Kenneth H. Cohn, you tell me more about it?” or “I’d like

MD, MBA, FACS to hear about that.”

communication is related to content—

the rest pertains to body language and Finally, reflect back to the speaker your

tone of voice.” A practicing surgeon as understanding of what has been said,

well as a and invite elaboration and clarification.

Responding is an integral part of active

consultant, Cohn is the author of Better listening and is especially important in

Communication for Better Care and situations involving conflict.

Collaborate for Success!

In active listening, through both words

and nonverbal behavior, you convey

these messages to the speaker:

• I understand your problem

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

• I know how you feel about it telephone conversation with an e-

• I am interested in what you are mail beginning, “As we discussed. .

saying ..”

• I am not judging you

For one-on-one communication, the

setting and timing can be critical to

Communication Is a Process

communicating effectively. Is a chat in

Effective communication requires

the corridor OK, or should this be a

paying attention to an entire process,

closed-door discussion? In your office

not just the content of the message.

or over lunch? Consider the mindset

When you are the messenger in this

and milieu of the communication

process, you should consider potential

receiver. Defer giving complex

barriers at several stages that can keep

information on someone’s first day

your intended audience from receiving

back from vacation or if you are aware

your message.

of situations that may be anxiety-

producing for that individual. Similarly,

Be aware of how your own attitudes,

when calling someone on the phone,

emotions, knowledge, and credibility

314 JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE • VOL. 3, ISSUE 6

©2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology

Downloaded from ascopubs.org by 114.122.9.140 on May 29, 2020 from

114.122.009.140

with the receiver might impede or alter ask initially if this is a convenient time

whether and how your message is to talk. Offer to set a specific time to

received. Be aware of your own body call back later.

language when speaking. Consider the

attitudes and knowledge of your Finally, organize content of the

intended audience as well. Diversity in message you want to communicate.

age, sex, and ethnicity or race adds to Make sure the information you are

the communication challenges, as do trying to What Not to Do When

different training backgrounds. Listening:

• Interrupt

Individuals from different cultures may

• Allow distractions

assign very different meanings to facial

expressions, use of space, and, • Judge

especially, gestures. For example, in • Criticize

some Asian cultures women learn that • Argue

it is disrespectful to look people in the • Use cliche´d phrases such as

eye and so they tend to have downcast “I know exactly howyou

eyes during a conversation. But in the feel,” “It’s not that bad,” or

United States, this body language could “You’ll feel better

be misinterpreted as a lack of interest tomorrow”

or a lack of attention.

• Get pulled into responding

Choose the right medium for the emotionally

message you want to communicate. • Change the subject or move

E-mail or phone call? Personal in a new direction

visit? Group discussion at a • Rehearse in your head what

meeting? Notes in the margin or a you plan to say next• Give

typed review? Sometimes more advice

than one medium is appropriate,

such as when you give the patient

written material to reinforce what convey is not too complex or lengthy

you have said, or when you follow- for either the medium you are using or

up a the audience. Use language appropriate

for the audience. With patients, avoid

medical jargon.

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Be Attuned to Body Language— ©2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology

Your Own and Others

Many nonverbal cues such as laughing, In oncology, as in most medical

gasping, shoulder shrugging, and practices, much of the work is done by

scowling have meanings that are well teams. Communication within a team

understood in our culture. But the calls for clarifying goals, structuring

meaning of some of these other more responsibilities, and giving and

subtle behaviors may not be as well receiving credible feedback.

known.1

“Physicians in general are at a

Hand movements. Our hands are our disadvantage because we haven’t been

most expressive body parts, conveying trained in team communication,” says

even more than our faces. In a Cohn. He points out that when he was

conversation, moving your hand behind in business school, as much as 30% to

your head usually reflects negative 50% of a grade came from team

thoughts, feelings, and moods. It may projects. “But how

be a sign of uncertainty, conflict, much of my grade in medical school

disagreement, frustration, anger, or was from team

dislike. Leaning back and clasping both projects? Zero.”

hands behind the neck is often a sign of

dominance. The lack of systematic education about

how teams work is the biggest hurdle

Blank face. Though theoretically for physicians in building a team

expressionless, a blank face sends a culture, according to Cohn. “We’ve

strong do not disturb message and is a learned team behaviors from our

subtle sign to others to keep a distance. clinical mentors, who also had no

Moreover, many faces have naturally formal team training. The styles we

down turned lips and creases of frown learn most in residency training are

lines, making an otherwise blank face ‘command and control’ and the ‘pace

appear angry or disapproving. setting approach,’ in which the leader

doesn’t specify what the expectations

Smiling. Although a smile may show are, but just expects people to follow

happiness, it is subject to conscious his or her example.”

control. In the United States and other

societies, for example, we are taught to Cohn says that both of those styles

smile whether or not we actually feel limit team cohesion. “Recognizing

happy, such as in giving a courteous one’s lack of training is the first step

greeting. [in overcoming the hurdle], then

understanding that one can learn

Tilting the head back. Lifting the chin these skills. Listening, showing

and looking down the nose are used sincere empathy, and being willing to

throughout the world as nonverbal experiment with new leadership

signs of superiority, arrogance, and styles, such as coaching and

disdain. developing a shared vision for the

future are key.”

Parting the lips. Suddenly parting

one’s lips signals mild surprise,

uncertainty, or unvoiced disagreement.

Lip compression. Pressing the lips

together into a thin line may signal

the onset of anger, dislike, grief,

sadness, or uncertainty.

Build a Team Culture

NOVEMBER 2007 • jop.ascopubs.org

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Stated goals and team values. An achieving the goal. They should also

effective team is one in which everyone understand the rolesResources

of others. Some

works toward a common goal. This expectations may relate to their regular

goal should be clearly articulated. In job duties; others may be one-time

Kenneth H. Cohn: Better Communication for Better

patient care, of course, the goal is the assignments specificCare:

to the team goal.

Mastering Physician-Administrator

best patient outcomes. But a team Leadership of the team may rotate Chicago,

Collaboration. on IL, Health Administration

approach is also highly effective in the basis of expertise.

Press, 2005,

reaching other goals in a physician

www.ache.org/pubs/redesign/productcatalog.

practice, such as decreasing patient Members must have resources available

waiting times, recruiting patients for a cfm?pcWWW1-2038

to accomplish their tasks, including

clinical trial, or developing a time, education and equipment needed

community education program. Every Kenneth H. Cohn: Collaborate for Success!

to reach the goal. Openly discuss what

member of the team must be committed is required to get theBreakthrough

job done andStrategies

find for Engaging Physicians,

to the team’s goal and objectives. Nurses,

solutions together as a team. and Hospital Executives. Chicago, IL, Health

Administration Press, 2006, www.ache.org/hap.cfm

Effective teams have explicit and Empowerment. Everyone on the team

appropriate norms, such as when should be empowered Suzette Haden

to work Elgin: Genderspeak: Men, Women, and

toward

meetings will be held and keeping the Gentle Art

the goal in his or her own job, in of Verbal Self-Defense. Hoboken, NJ,

information confidential. Keep in mind addition to Wiley, 1993

that it takes time for teams to mature

and develop a climate of trust and Jon R. Katzenbach, Douglas K. Smith: The Wisdom of

mutual respect. Groups do not progress Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization.

from forming to performing without New York, NY, Harper Business, 1994

going through a storming phase in

which team members negotiate Sharon Lippincott: Meetings: Do’s, Don’ts, and

assumptions and expectations for Donuts. Pittsburgh, PA, Lighthouse Point Press, 1994

behavior.2

Kenneth W. Thomas: Intrinsic Motivation at Work:

Clear individual expectations. All the Building Energy and Commitment. San Francisco, CA,

team members must be clear about Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2000

what is expected of them individually

and accept their responsibility for

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Make Meetings Work for Your Team

A good meeting is one in which team goals are

introduced or reinforced and solutions are generated.

The first rule—meet in person only if it’s the best

format to accomplish what you want. You don’t need

a meeting just to report information. Here are tips for

facilitating an effective meeting:

Don’t meet just because it’s scheduled. If there are

no issues to discuss, don’t hold the meeting just

because it’s Tuesday and that’s when you always

meet.

Use an agenda. Circulate a timed agenda beforehand

and append useful background information.

Participants should know what to expect. If it’s a short

meeting or quickly called, put the agenda on a flipchart

or board before people arrive.

Structure input. Promote the team culture by

making different individuals responsible for specific

agenda items. Follow-up on previous task

assignments as the first agenda item to hold group

members accountable for the team’s success.

Limit the meeting time. Use the timed agenda to

stay on track. If the discussion goes off on a tangent,

bring the group back to the objective of the topic at

hand. If it becomes clear that a topic needs more

time, delineate the issues and the involved parties and

schedule a separate meeting.

Facilitate discussion. Be sure everyone’s ideas are

heard and that no one dominates the discussion. If

two people seem to talk only to each other and not to

the group as a whole, invite others to comment. If

only two individuals need to pursue a topic, suggest

that they continue to work on that topic outside the

meeting.

Set ground rules up front. Keep meetings

constructive, not a gripe session. Do not issue

reprimands, and make it clear that the meeting is to

be positive and intended for updates, analysis,

problem solving, and decision making. Create an

environment in which disagreement and offering

alternative perspectives are acceptable. When

individuals do offer opposing opinions, facilitate

open discussion that focuses on issues and not

personalities.

Circulate a meeting summary before the next

meeting. Formal minutes are appropriate for some

meetings. But in the very least, a brief summary of

actions should be prepared. Include decisions reached

and assignments made, with deadlines for follow-up at

the next meeting.

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Except among friends who know you Professional Advisors: They’re

well, stay away from sarcasm in e-mail Worth It—J Oncol Pract 3:162-

messages. The receiver does not have 166, 2007

the benefit of your tone of voice and

body language to help interpret your Building and Maintaining a

communication. When delivering Referral Base—J Oncol Pract

comments that are even slightly critical, 3:227-230, 2007

it’s better to communicate in person or

in a phone call than to do so in an e-

Malpractice Insurance: What

mail. Something you wrote with good

intentions and an open mind or even You Need to Know— J Oncol

with humor can be interpreted as Pract 3:274-277, 2007

nitpicky, negative, and destructive, and

can be forwarded to others. Joining a Practice As a

Shareholder—J Oncol Pract

Because we use e-mail for its speed, it’s 3:41-44, 2007

easy to get in the habit of dashing off a

message and hitting the “send” button. spelling typos are the least of the

We count on the automatic spell-check problems in communicating

(and you should have it turned on as effectively.

your default option) to catch your

errors. But Take the time to read through your

message. Is it clear? Is it organized? Is

References it concise? See if there is anything that

1. Givens DB: The Nonverbal Dictionary of could be misinterpreted or raises

Gestures, Signs, & Body Language unanswered questions. The very speed

NOVEMBER 2007 • jop.ascopubs.org with which we dash off e-mail

messages makes e-mail the place in

which we are most likely to

©2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology

communicate poorly.

Cues.

http://members.aol.com/nonverbal2/diction1.htm

Finally, don’t forget to supply

appropriate contact information,

More Strategies for Career including phone numbers or alternative

Success! e-mail addresses, for responses or

questions.

Deciding About Practice

Options—J Oncol Pract 2: 187- Conclusion

190, 2006 Conflict is inevitable in times of rapid

change. Effective communication helps

The Interview: Make it Work for one avoid conflict and minimize its

You—J Oncol Pract 2:252-254, adverse consequences when it does

2006 occur. The next issue of Strategies for

Career Success will cover conflict

Employment Contracts: What to management.

Look for—J Oncol Pract 2:308-

311, 2006 DOI: 10.1200/JOP.0766501

Principles and Tactics of

Negotiation—J Oncol Pract 2. Cohn KH, Peetz ME: Surgeon frustration:

3:102-105, 2007 Contemporary problems, practical solutions.

Contemporary Surg 59:76–85, 2003.

www.healthcarecollaboration.com

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from ascopubs.org by 114.122.9.140 on May 29, 2020 from 114.122.009.140

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Journal of

Oncology

Practice

From the Editor’s Desk

Challenges and Solutions

Douglas W. Blayney, MD ..............................289

From the ASCO President

Focusing on a Shared Goal...............................290

Perspective

Standard of Care Versus Standards of Care in Oncology: A

Not So Subtle Distinction

Maurie Markman, MD................................291

Original Research

Prevalence and Predictors of Complementary Therapy Use

in

Advanced-Stage Breast Cancer Patients

Abigail M. Gross, Qin Liu, PhD, and Susan Bauer-Wu,

PhD, RN.............................................292

Cover Story

Medicare’s Coverage With Evidence Development: A

PolicyMaking Tool in Evolution ...............................296

Business of the Business

Practical Tips

Reporting National Drug Code Numbers on Medicaid

Claims

........................................................302

The Voice of ASCO

ASCO’s Clinical Practice Committee

The Internet Immigrant

Therese M. Mulvey, MD ...............................303

State Affiliate News

Responding to the Impending Realignment of Medicare

Administrative Contractors ..............................304

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Clinical Research Oncology Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Adjuvant Radiation

Minimizing Research Delays: Identifying Successful Therapy for Stages I-IIIA Resectable Non–Small-Cell Lung

Strategies to Keep a Clinical Trial Moving Cancer Guideline .......................................332

Forward .................306 American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 Update of

Weighing the Impact of the Health Insurance Portability Recommendations for the Use of Tumor Markers in

and Breast Cancer...........................................336

Accountability Act on Clinical Research ..................308 Letter to the Editor

For Your Patients QOPI, EHRs, and Quality Measurement

PLWC Resources Joel W. Goldwein, MD, and Christopher M. Rose,

Cancer and the Holidays: ASCO’s Resources for Patients

MD....340 Acknowledgment ...................................341

and Caregivers ..........................................309

Journal of Oncology Practice (ISSN 1554-7477) is published 6 times a

Contents year (January, March, May, July, September, November), by American

Society of Clinical

Oncology, 1900 Duke St, Suite 200, Alexandria, VA 22314. Periodicals

postage pending at Alexandria, VA, and at additional mailing offices.

Volume 3 Issue 6, November 2007 Publication Mail

Agreement Number pending. Editorial correspondence should be

addressed to Douglas W. Blayney, MD, Journal of Oncology Practice,

330 John Carlyle St, Suite 300, Alexandria, VA 22314; telephone, 703-

797-1900; fax, 703-684-8720; e-mail, jopsubmissions@asco.org. ©

American Society of Clinical Oncology

POSTMASTER: Send change of address to Journal of Oncology

Training and Development Practice, American Society of Clinical Oncology, 1900 Duke St, Suite

200, Alexandria, VA 22314. Nonmembers send change of address to

Focus on Staff Journal of Oncology Practice, Customer Service, 330 John Carlyle St,

Screening New Hires? Identifying Potentially Suite 300, Alexandria, VA 22314.

Disruptive Players.......................................310 Annual subscription rates (effective through August 31, 2007): United

States and possessions: ASCO active-allied, $50; ASCO affiliate, $50;

Focus on Quality nonmember individual US, $125; nonmember individual international,

$145; in-training US, $65; in-training international, $75; institutional US,

Physician-Level Oncology Measures ......................312 $200; institutional international, $250; single issue US, $25; single issue

international, $35.

Strategies for Career Success To receive in-training rate, orders must be accompanied by name of

affiliated institution, date of term, and the signature of

Developing Effective Communication Skills ..............314 program/residency coordinator on institution letterhead. Orders will be

billed at individual rate until proof of status is received. Current prices

IT Help Desk are in effect for back volumes and back issues. Back issues sold in

conjunction with a subscription rate on a prorated basis. Subscriptions

Selecting an Electronic Health Record for Your are accepted on a calendar-year basis. Prices are subject to change

Practice ...318 without notice. Single issues, both current and back, exist in limited

quantities, and are offered for sale subject to availability.

Partners in Cancer Care

The Physicians’ Electronic Health Record Coalition

Downloaded from ascopubs.org by 114.122.9.140 on May 29, 2020 from

Peter Basch, MD, FACP ...............................321 114.122.009.140

Current Clinical Issues

How I Treat . . .

How We Maintain Bone Health in Early-Stage Breast

Cancer

Patients on Aromatase Inhibitors

Ting Bao, MD, and Nancy E. Davidson, MD............323

Guideline Summaries

American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 Clinical

Practice

Guideline Recommendations for Venous

Thromboembolism

Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer.......326

Commentary: ASCO Clinical Practice Guidelines and

Beyond

Gary H. Lyman, MD, MPH........................330

Cancer Care Ontario and American Society of Clinical

Copyright © 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- Handouts - Week 2Документ5 страницHandouts - Week 2Keanna Yasmin AposagaОценок пока нет

- Skills in Effective CommunicationДокумент4 страницыSkills in Effective Communicationpaakwesi1015Оценок пока нет

- The Features of Effective CommunicationДокумент7 страницThe Features of Effective Communicationkawaiijoon100% (1)

- Week 5 QuizДокумент6 страницWeek 5 QuizWayne Dolorico MillamenaОценок пока нет

- Interpersonal CommunicationДокумент16 страницInterpersonal CommunicationMuhammad Zun Nooren BangashОценок пока нет

- Purp Com PrelimДокумент10 страницPurp Com Prelimhyajiko5Оценок пока нет

- Week 2 BpsДокумент19 страницWeek 2 BpsEesha waseemОценок пока нет

- Conquering Your Fear of Speaking in PublicДокумент29 страницConquering Your Fear of Speaking in PublicIrtiza Shahriar ChowdhuryОценок пока нет

- Strategies To Avoid Communication BreakdownДокумент3 страницыStrategies To Avoid Communication BreakdownSai RiveraОценок пока нет

- Oral Com-03Документ5 страницOral Com-03rhen reluyaОценок пока нет

- Maj 18 HandoutДокумент2 страницыMaj 18 HandoutMarch MarchОценок пока нет

- Talk with Confidence: A Comprehensive Guide to Effortless Communication with Anyone, Anytime, About AnythingОт EverandTalk with Confidence: A Comprehensive Guide to Effortless Communication with Anyone, Anytime, About AnythingОценок пока нет

- Copyright Jurnal 1Документ15 страницCopyright Jurnal 1Novian IlhamОценок пока нет

- Oral Communication 2 (Autosaved)Документ57 страницOral Communication 2 (Autosaved)Mohcine BenmouloudОценок пока нет

- Clear A Path For CommunicationДокумент2 страницыClear A Path For Communicationprofthadaskew4433Оценок пока нет

- Lesson 6 Oral CommДокумент2 страницыLesson 6 Oral Commtracyallenmontes48Оценок пока нет

- Love, Logic and the Art of Negotiation: A Guide to Improving Relationship CommunicationОт EverandLove, Logic and the Art of Negotiation: A Guide to Improving Relationship CommunicationОценок пока нет

- The Power Of Communication How To Connect And Influence Others: Effective Communication Is Essential In Both Professional And Personal LifeОт EverandThe Power Of Communication How To Connect And Influence Others: Effective Communication Is Essential In Both Professional And Personal LifeОценок пока нет

- Stem 11 Persistence ModulesДокумент33 страницыStem 11 Persistence Moduleshannamaemanaog4Оценок пока нет

- Verbal and Non - Verbal Behavior in A Speech ContextДокумент12 страницVerbal and Non - Verbal Behavior in A Speech ContextkkuyyytedvbОценок пока нет

- 2ND Quarter Module Oral Communication 11Документ65 страниц2ND Quarter Module Oral Communication 11Kem KemОценок пока нет

- How To Improve Your Communicating Skills?Документ4 страницыHow To Improve Your Communicating Skills?Aldwyn Jahziel C. OngОценок пока нет

- Communication Is At The Core Of Every Business And Relationship: A Short CourseОт EverandCommunication Is At The Core Of Every Business And Relationship: A Short CourseОценок пока нет

- RBR - Act. Sheet June10Документ5 страницRBR - Act. Sheet June10reaОценок пока нет

- Open Windows Culture - The Christian's Workbook: Practical Tools to Help You Rewrite Your Culture and the Culture of Your ChurchОт EverandOpen Windows Culture - The Christian's Workbook: Practical Tools to Help You Rewrite Your Culture and the Culture of Your ChurchОценок пока нет

- Purc Finals PSA (Public Service Announcement) : What Makes A Psa Effective?Документ13 страницPurc Finals PSA (Public Service Announcement) : What Makes A Psa Effective?Dustin Delos SantosОценок пока нет

- CommunicationДокумент3 страницыCommunicationIanna Marie D TacoloyОценок пока нет

- The Complete Communication & People Skills Training: Master Small Talk, Charisma, Public Speaking & Start Developing Deeper Relationships & Connections- Learn to Talk To AnyoneОт EverandThe Complete Communication & People Skills Training: Master Small Talk, Charisma, Public Speaking & Start Developing Deeper Relationships & Connections- Learn to Talk To AnyoneОценок пока нет

- Reviewer NCM103A CommunicationДокумент7 страницReviewer NCM103A CommunicationAthaliah WalterОценок пока нет

- Oral CommДокумент28 страницOral CommStephen CatorОценок пока нет

- Listening CompetencyДокумент23 страницыListening CompetencySidra NazОценок пока нет

- Week 5 V.2Документ2 страницыWeek 5 V.2Wayne Dolorico MillamenaОценок пока нет

- EffectivePresentation Handout 1 PDFДокумент8 страницEffectivePresentation Handout 1 PDFsuci fithriyaОценок пока нет

- Pcom ActiviyДокумент4 страницыPcom ActiviyMarked BrassОценок пока нет

- Elp 2 NotesДокумент81 страницаElp 2 NotesJohn Louie IrantaОценок пока нет

- STRATEGIES TO AVOID COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN (Oral ComM3Q1)Документ4 страницыSTRATEGIES TO AVOID COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN (Oral ComM3Q1)Joshua Lander Soquita CadayonaОценок пока нет

- Langka Is GR7 Q4 LC2 EditedДокумент10 страницLangka Is GR7 Q4 LC2 EditedLARLY JOYCE M SAN FELIPEОценок пока нет

- Module 2 Oral CommunicationДокумент10 страницModule 2 Oral CommunicationCatherine PalmaОценок пока нет

- The Framework of Communication: Learning OutcomesДокумент6 страницThe Framework of Communication: Learning OutcomesAstxilОценок пока нет

- Communication Skills: Learn How to Talk to Anyone, Read People Like a Book, Develop Charisma and Persuasion, Overcome Anxiety, Become a People Person, and Achieve Relationship Success.От EverandCommunication Skills: Learn How to Talk to Anyone, Read People Like a Book, Develop Charisma and Persuasion, Overcome Anxiety, Become a People Person, and Achieve Relationship Success.Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (45)

- Ge Elec 1 - Chapter 1Документ4 страницыGe Elec 1 - Chapter 1Winter SongОценок пока нет

- Reviewer On Oral Communication For 2nd QuarterДокумент10 страницReviewer On Oral Communication For 2nd QuarterNiño Ryan ErminoОценок пока нет

- NCR Final SHS Oral-Com Q1 M1Документ18 страницNCR Final SHS Oral-Com Q1 M1Aaron James Quijano100% (1)

- ORAL-COMMUNICATION11 Q1 Module3Документ4 страницыORAL-COMMUNICATION11 Q1 Module3Muzically InspiredОценок пока нет

- Communication Means Talking Together: How You Can Inspire Your Team and Lead with PurposeОт EverandCommunication Means Talking Together: How You Can Inspire Your Team and Lead with PurposeОценок пока нет

- Barriers of CommunicationДокумент55 страницBarriers of CommunicationHeide Cristy PorniaОценок пока нет

- Oralcom ReviwerДокумент24 страницыOralcom ReviwerKathlene ManaigОценок пока нет

- 74 76communication BarriersДокумент4 страницы74 76communication BarrierscpayagОценок пока нет

- Communication Conversastion Skills 1234278345934814 3+com ProcessДокумент71 страницаCommunication Conversastion Skills 1234278345934814 3+com Processankurbehl1989100% (1)

- Unit 2, Business CommunicationДокумент33 страницыUnit 2, Business Communicationcoder ninjaОценок пока нет

- LSRW Skills: A Way To Enhance CommunicationДокумент4 страницыLSRW Skills: A Way To Enhance CommunicationIJELS Research JournalОценок пока нет

- The Language of Yes: How to Use Persuasive Words and Phrases to Get What You WantОт EverandThe Language of Yes: How to Use Persuasive Words and Phrases to Get What You WantОценок пока нет

- TopicДокумент18 страницTopicDestrofan GamingОценок пока нет

- ReviewerДокумент22 страницыReviewerKeena EstebanОценок пока нет

- Learning Activity Sheet (Las) : Senior High SchoolДокумент3 страницыLearning Activity Sheet (Las) : Senior High SchoolEarl Vann UrbanoОценок пока нет

- Engl7 Q4 W1-EmployingInterpesonalCommunicationStrategies Garcia V2-5-ReviewedДокумент12 страницEngl7 Q4 W1-EmployingInterpesonalCommunicationStrategies Garcia V2-5-ReviewedAlvin SevillaОценок пока нет

- Overcoming Communicati ON BarriersДокумент13 страницOvercoming Communicati ON BarriersJasmine CristobalОценок пока нет

- THE SILENT CONVERSATION: Understanding the Power of Nonverbal Communication in Everyday Interactions (2024 Guide for Beginners)От EverandTHE SILENT CONVERSATION: Understanding the Power of Nonverbal Communication in Everyday Interactions (2024 Guide for Beginners)Оценок пока нет

- CSSD Question Bank by DKДокумент18 страницCSSD Question Bank by DKKumar DineshОценок пока нет

- Intro. To Linguistics: Comparative Linguistics by Rahmi Fhonna, MaДокумент12 страницIntro. To Linguistics: Comparative Linguistics by Rahmi Fhonna, MaDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Morphology: Rahmi Fhonna, MaДокумент9 страницMorphology: Rahmi Fhonna, MaDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Syntactic Categories: Rahmi Fhonna, MaДокумент9 страницSyntactic Categories: Rahmi Fhonna, MaDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Semantics: Rahmi Fhonna, MaДокумент25 страницSemantics: Rahmi Fhonna, MaDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Oca Nurjannah 180203074Документ3 страницыOca Nurjannah 180203074DANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Grammar and Communication DoДокумент4 страницыGrammar and Communication DoDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Listen To The ConversationДокумент2 страницыListen To The ConversationDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Oca Nurjannah 180203074 PDFДокумент3 страницыOca Nurjannah 180203074 PDFDANDY RADITYAОценок пока нет

- Domestic and Foreign Policy Essay: Immigration: Salt Lake Community CollegeДокумент6 страницDomestic and Foreign Policy Essay: Immigration: Salt Lake Community Collegeapi-533010636Оценок пока нет

- German Monograph For CannabisДокумент7 страницGerman Monograph For CannabisAngel Cvetanov100% (1)

- LittorinidaeДокумент358 страницLittorinidaeSyarif Prasetyo AdyutaОценок пока нет

- Test Statistics Fact SheetДокумент4 страницыTest Statistics Fact SheetIra CervoОценок пока нет

- Motivational Speech About Our Dreams and AmbitionsДокумент2 страницыMotivational Speech About Our Dreams and AmbitionsÇhärlöttë Çhrístíñë Dë ÇöldëОценок пока нет

- Key Performance IndicatorsДокумент15 страницKey Performance IndicatorsAbdul HafeezОценок пока нет

- Linear Space-State Control Systems Solutions ManualДокумент141 страницаLinear Space-State Control Systems Solutions ManualOrlando Aguilar100% (4)

- Spisak Gledanih Filmova Za 2012Документ21 страницаSpisak Gledanih Filmova Za 2012Mirza AhmetovićОценок пока нет

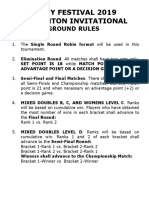

- Ground Rules 2019Документ3 страницыGround Rules 2019Jeremiah Miko LepasanaОценок пока нет

- Teuku Tahlil Prosiding38491Документ30 страницTeuku Tahlil Prosiding38491unosa unounoОценок пока нет

- Report Body of IIDFC - 2Документ120 страницReport Body of IIDFC - 2Shanita AhmedОценок пока нет

- Ergonomics For The BlindДокумент8 страницErgonomics For The BlindShruthi PandulaОценок пока нет

- Music 20 Century: What You Need To Know?Документ8 страницMusic 20 Century: What You Need To Know?Reinrick MejicoОценок пока нет

- Framework For Marketing Management Global 6Th Edition Kotler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFДокумент33 страницыFramework For Marketing Management Global 6Th Edition Kotler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFWilliamThomasbpsg100% (9)

- Statistical MethodsДокумент4 страницыStatistical MethodsYra Louisse Taroma100% (1)

- Prime White Cement vs. Iac Assigned CaseДокумент6 страницPrime White Cement vs. Iac Assigned CaseStephanie Reyes GoОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 Front Sheet: Qualification BTEC Level 5 HND Diploma in Computing Unit Number and Title Submission DateДокумент18 страницAssignment 1 Front Sheet: Qualification BTEC Level 5 HND Diploma in Computing Unit Number and Title Submission DatecuongОценок пока нет

- Business Administration: Hints TipsДокумент11 страницBusiness Administration: Hints Tipsboca ratonОценок пока нет

- Chapter 019Документ28 страницChapter 019Esteban Tabares GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Cruz-Arevalo v. Layosa DigestДокумент2 страницыCruz-Arevalo v. Layosa DigestPatricia Ann RueloОценок пока нет

- Right Hand Man LyricsДокумент11 страницRight Hand Man LyricsSteph CollierОценок пока нет

- Preliminaries Qualitative PDFДокумент9 страницPreliminaries Qualitative PDFMae NamocОценок пока нет

- Hero Cash Cash Lyrics - Google SearchДокумент1 страницаHero Cash Cash Lyrics - Google Searchalya mazeneeОценок пока нет

- Dark Witch Education 101Документ55 страницDark Witch Education 101Wizard Luxas100% (2)

- Oldham Rules V3Документ12 страницOldham Rules V3DarthFooОценок пока нет

- Desire of Ages Chapter-33Документ3 страницыDesire of Ages Chapter-33Iekzkad Realvilla100% (1)

- CLASS 12 PracticalДокумент10 страницCLASS 12 PracticalWORLD HISTORYОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Catfish ProductionДокумент5 страницLiterature Review On Catfish Productionafmzyodduapftb100% (1)

- ChitsongChen, Signalsandsystems Afreshlook PDFДокумент345 страницChitsongChen, Signalsandsystems Afreshlook PDFCarlos_Eduardo_2893Оценок пока нет

- Sophia Vyzoviti - Super SurfacesДокумент73 страницыSophia Vyzoviti - Super SurfacesOptickall Rmx100% (1)