Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Construction Project Cost Escalation Factors

Загружено:

Brian LukeАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Construction Project Cost Escalation Factors

Загружено:

Brian LukeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/245298365

Construction Project Cost Escalation Factors

Article in Journal of Management in Engineering · October 2009

DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2009)25:4(221)

CITATIONS READS

82 6,280

4 authors, including:

Jennifer Shane Keith R. Molenaar

Iowa State University University of Colorado Boulder

71 PUBLICATIONS 435 CITATIONS 127 PUBLICATIONS 1,972 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Alternative Project Delivery Methods and Infrastructure Procurement View project

Project Performance View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Jennifer Shane on 21 October 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Construction Project Cost Escalation Factors

Jennifer S. Shane, A.M.ASCE1; Keith R. Molenaar, M.ASCE2; Stuart Anderson, M.ASCE3; and

Cliff Schexnayder, Dist.M.ASCE4

Abstract: Construction projects, private and public alike, have a long history of cost escalation. Transportation projects, which typically

have long lead times between planning and construction, are historically underestimated, as shown through a review of the cost growth

experienced with the Holland Tunnel. Approximately 50% of the active large transportation projects in the United States have overrun

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

their initial budgets. A large number of studies and research projects have identified individual factors that lead to increased project cost.

Although the factors identified can influence privately funded projects the effects are particularly detrimental to publicly funded projects.

The public funds available for a pool of projects are limited and there is a backlog of critical infrastructure needs. Therefore, if any project

exceeds its budget other projects are dropped from the program or the scope is reduced to provide the funds necessary to cover the cost

growth. Such actions exacerbate the deterioration of a state’s transportation infrastructure. This study is an anthology and categorization

of individual cost increase factors that were identified through an in-depth literature review. This categorization of 18 primary factors

which impact the cost of all types of construction projects was verified by interviews with over 20 state highway agencies. These factors

represent documented causes behind cost escalation problems. Engineers who address these escalation factors when assessing future

project cost and who seek to mitigate the influence of these factors can improve the accuracy of their cost estimates and program budgets.

DOI: 10.1061/共ASCE兲0742-597X共2009兲25:4共221兲

CE Database subject headings: Construction costs; Estimation; Construction management; Planning.

Introduction budgets over the time span between project initiation and the

completion of construction. The development of cost estimates

Historically large construction projects have been plagued by that accurately reflect project scope, economic conditions, and are

cost and schedule overruns 共Flyvbjerg et al. 2002兲. In too many attuned to community interest and the macroeconomic conditions

cases, the final project cost has been higher than the cost esti- provide a baseline cost that management can use to impart disci-

mates prepared and released during initial planning, preliminary pline into the design process. Projects can be delivered on budget

engineering, final design, or even at the start of construction but that requires a good starting estimate, an awareness of factors

that can cause cost escalation, and project management discipline.

共“Megaprojects need more study up front to avoid cost overruns.”

When discipline is lacking, significant cost growth on one project

2002兲. The ramifications of differences between early project cost

can raze the larger program of projects because funds will not be

estimates and bid prices or the final cost of a project can be

available for future projects that are programmed for construction.

significant. Over the time span between project initiation 共concept

development兲 and the completion of construction many factors

may influence the final project costs. This time span is normally History—Holland Tunnel Case Study

several years in duration but for the highly complex and techno-

logically challenging projects it can easily exceed 10 years. A history of past project experiences can serve one well in under-

standing the challenges of delivering a quality project on budget.

Organizations face a major challenge in controlling project

Repeatedly, the same problems cause project cost escalation and

1

much wisdom can be gained by studying the past. The Holland

Assistant Professor, Dept. of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Tunnel was, when it opened in 1927, the longest underwater tun-

Engineering, Iowa State Univ., 498 Town Engineering, Ames, IA 50011

nel ever constructed and it was also the first mechanically venti-

共corresponding author兲. E-mail: jsshane@iastate.edu

2

Associate Professor, Dept. of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural lated underwater tunnel. Its initial cost estimate was made by the

Engineering, Univ. of Colorado, UCB 428, Boulder, CO 80302. E-mail: renowned civil engineer George Washington Goethals.

Keith.Molenaar@colorado.edu A review of the Holland Tunnel project serves to highlight the

3

Professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Civil Engineering Lab Build- critical issues associated with estimating the costs of large com-

ing Room 115, Texas A&M Univ., College Station, TX 77843-3136. plex projects and the fact that even the most distinguished engi-

E-mail: s-anderson5@tamu.edu neers have trouble assessing cost drivers beyond the physical

4

Eminent Scholar Emeritus, Del E. Webb School of Construction, characteristics of a project. Many times there is no recognition of

Arizona State Univ., P.O. Box 6700, Chandler, AZ 85246. E-mail: the cost drivers operating outside the project’s physical configu-

cliff.s@asu.edu

ration.

Note. This manuscript was submitted on February 27, 2008; approved

on February 9, 2009; published online on September 15, 2009. Discus-

A joint New York and New Jersey commission in 1918 rec-

sion period open until March 1, 2010; separate discussions must be sub- ommended a transportation tunnel under the river 共“Urges new

mitted for individual papers. This paper is part of the Journal of tunnel under the Hudson.” 1918; “Ask nation to share in tunnel to

Management in Engineering, Vol. 25, No. 4, October 1, 2009. ©ASCE, Jersey.” 1918兲. The automobile was emerging as the predominate

ISSN 0742-597X/2009/4-221–229/$25.00. means of transportation and it was decided that this tunnel should

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009 / 221

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

be for vehicular traffic. As a result the tunnel would employ new $4,422,000. Holland also decided to substitute cast-steel for cast-

ventilation technologies to purge the exhaust gases produced by iron to increase the strength and safety factors of the tunnel—

the internal combustion engine. more scope creep. Last, the New Jersey ventilation shafts had to

Eleven designs were considered for the tunnel, most notably, be redesigned along with their corresponding foundations at a

one by the engineer recently responsible for finishing the Panama cost of $700,000 due to unexpected soil conditions—unforeseen

Canal, George Washington Goethals. He envisioned a single, conditions. All of these changes increased the estimate to over

bilevel tunnel with opposing traffic on each level. Goethals $42.5 million.

made a planning project cost estimate of $12 million and 3 years New funds were appropriated and it was believed that these

for construction. World War I had consumed much of the nation’s were sufficient to complete the project, but by February of 1926,

steel and iron production, so his design made use of cement there was another increase of $3,200,000 共“$3,200,000 more

blocks as the tunnel’s structural shell. His design was the front- asked for tunnel.” 1926兲. The commission explained that the new

running plan 共“Hudson vehicle tube.” 1919兲 but he had respon- costs were due to increases in labor and material costs—challenge

sibilities elsewhere and was not named chief engineer for the in controlling cost. At this time Holland died of heart failure and

project. his assistant, Milton H. Freeman, took over as chief engineer only

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Clifford M. Holland was named to head the project along with to die of pneumonia 4 months later. Ole Singstad, the designer of

a board of five consulting engineers 共“Name interstate tunnel en- the ventilation system then became chief engineer and brought the

gineers.” 1919兲. Holland came to the project with vast experience project to completion. Having three different chief engineers

in constructing subways and tunnels in New York. The cost of the within 5 months created confusion—unforeseen events. In April

project was taken to be $12 million, Goethals’ planning estimate. of 1924 water rushed into one of the tunnels from a leak forcing

Holland produced a report in February of 1920 based on his workers to make a hasty escape—more unforeseen conditions. A

analysis of the Goethals’ design of the project. His findings were final appropriation was requested in early 1927 brought the total

not what had been expected. Holland found project cost to $48,400,000. On November 13 of 1927 the tunnel

• Goethals’ width of 7.47 m would not accommodate the volume officially opened 共“Work on tunnel began 7 years ago.” 1927兲.

of traffic.

• Concrete blocks would not withstand the structural loads ex-

Flyvbjerg Study

erted on the tunnel.

• The construction methods required by Goethals’ design were Estimating problems are not limited to a particular owner or

completely untried. project type. Research has shown that project costs are consis-

• The estimated cost of construction was grossly low. tently underestimated. In one study by Flyvbjerg et al. 共2002兲, it

• The work could not be completed in 3 years. was found that this underestimation occurs in 9 out of 10 trans-

The board of consulting engineers gave unanimous support for portation infrastructure projects around the world. Flyvberg et al.

Holland’s analysis. Holland then presented a design of his own 共2002兲 has preformed numerous studies on the cost of mega

which was supported unanimously by the consulting engineers. projects and risk, particularly from the prospective of urban

Holland’s design, which was a major scope change, called for policy and planning. These studies have been widely cited by

twin cast-iron tubes. One advantage was that construction would public officials. The tone of his writing seems to imply that engi-

follow established methods of tunnel construction that had been neers deliberately underestimate the cost of projects and other

implemented for rail tunnels under the East River and further up researchers have made similar conclusions that purposeful under-

the Hudson. Holland estimated the cost at $28,669,000 共“Asks estimation of project cost occurs early in project development to

$28,669,000 for Jersey tube.” 1920兲 and construction time at 3 gain project funding 共Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Pickrell 1992兲.

1/2 years. Yet other studies such as those by the United States General Ac-

Debate about the tunnel design continued for more than a year counting Office 共GAO兲 concentrate more on identifying the

creating disagreements between the New York and New Jersey causes of project cost growth and do not blame engineers as cul-

Commissions and delaying the work—a schedule change. A dis- prits deliberately underestimating cost. The GAO reports do paint

agreement about awarding a contract on the New Jersey side fur- a picture of engineers not properly considering all of the factors

ther delayed the start of construction and added over half of a that can impact project cost 共GAO 1997, 2002兲. Not withstanding

million dollars in cost. Construction started on the New York side Flyvbjerg et al.’s 共2002兲 reading of the data, his reports are an

in October of 1920 and in late December 1921 the New Jersey excellent source of world wide data on project cost growth as he

portion of the tunnel was bid 共“Way all cleared for Jersey tunnel.” has been meticulous in his data acquisition methods.

1921兲. The mandated completion date was December 31, 1926. The data of Flyvbjerg et al. 共2002兲 indicate that worldwide

The construction schedule had now grown to 5 years. transportation construction costs are on average 28% higher than

Estimated project cost increased multiple times throughout the their estimated cost. Rail projects have the worst project underes-

early years of construction as a result of scope creep, schedule timation track record with an average cost escalation of 44.7%

delays, and inflation. Increased traffic forecast necessitate larger 共Table 1兲. Bridge projects follow at 33.8% being underestimated

entrance/exit plazas and acquisition of more right of way 共“Ve- and then road projects with an average cost escalation of 20.4%.

hicular tube is growing.” 1923兲. Then increases in material and Transportation projects on a whole are found to experience aver-

labor costs had added another $6 million to the project—inflation. age cost escalation of 27.6%. Underestimation or inaccurate cost

By the beginning of 1924, the mid-1923 reestimated costs had estimation appears to be found throughout the world, though

been increased by $14,000,000 共“Vehicular tunnel cost up North America fares better than Europe. Additionally, Flyvbjerg

$14,000,000.” 1924兲 due to functional and aesthetic factors— et al. 共2002兲 conclude that there is no indication that estimating

scope creep. More intricate roadway designs for approaches, wid- practices have improved over the past 70 years, the time period

ening of the approach roadways, and architectural treatments from which his sample was taken.

increased the costs—more scope creep. Redesign of the ventila- Cost increases have plagued the industry for years as indicated

tion system added 15.24 cm to the tunnel diameter and by the Holland Tunnel project and summarized more recently by

222 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

Table 1. Inaccuracy of Transportation Project Cost Estimates 共Flyvbjerg et al. 2002兲

All projects Europe North America

Average cost Average cost Average cost

Number escalation Number escalation Number escalation

Project type of cases 共%兲 of cases 共%兲 of cases 共%兲

Rail 58 44.7 23 34.2 19 40.8

Bridge 33 33.8 15 43.4 18 25.7

Road 167 20.4 143 22.4 24 8.4

All projects 258 27.6 181 28.7 61 23.6

Flyvbjerg et al. 共2002兲. Before researchers and industry alike can While these individual factors are widely known they have not

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

work to improve cost estimating, the factors that lead to increases been captured before in a single publication. This compilation is

in cost estimates must first be identified and classified to allow for necessary so that researchers and industry can identify global

the development of appropriate mitigation strategies. strategies to address the factors, and then methods and tools to

implement the strategies. This paper provides a framework for

categorizing factors based on internal versus external sources,

Problem which is particularly relevant to transportation projects.

Managing capital construction projects requires the coordination

of a multitude of human, organizational, technical, and natural Methodology

resources. Quite often, the engineering and construction com-

plexities of such projects are overshadowed by economic, soci- The cost escalation factors that lead to project cost growth have

etal, and political challenges. These challenges influence cost and been documented through a large number of studies. Studies have

are factors which engineers are often least equipped to appreciate. identified factors individually or by groups. Each factor presents a

Within the transportation industry, project cost escalation has at- challenge to an agency seeking to produce accurate project cost

tracted management and stakeholder attention at federal, state, estimates. As part of a larger study seeking to improve cost esti-

regional, and local levels. Facility owners in the United States mates and management of costs from project conception to bid

face a major challenge in controlling project budgets over the day, a thorough literature review was conducted to identify fac-

time span between project initiation and the completion of con- tors that influence cost estimates 共Anderson et al. 2006兲. The lit-

struction. Over this time span there are many factors that can erature review included exploration of research reports and

influence a project’s final costs. publications, government reports, news articles, and other pub-

All major projects can take years to move from planning to lished sources.

construction and for highly complex and technologically chal- Upon completion of the literature review the factors were ana-

lenging projects, the duration can easily be a decade or more. lyzed and categorized by the researchers into factors that drive the

Over that period, changes to the project scope and its definition cost increases experienced by transportation construction projects.

can occur. During the early stages of a project many factors in- This was accomplished by triangulation where multiple investi-

fluence project costs. gators or data sources suggested the same factor. This categoriza-

One study found that 50% of the large active transportation tion took the individual factors which had been identified in

projects in the United States had overrun their initial budgets previous research and established a global framework for address-

共Sinnette 2004兲. News reports of high profile project cost escala- ing the issue of project cost escalation. Upon final categorization

tion cause the public to lose confidence in the ability of agencies the cost escalation factor framework was verified through trian-

to effectively perform their responsibilities. For example, the Bos- gulation of data from interviews with more than 20 state highway

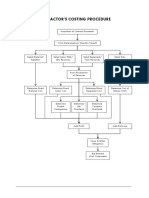

ton Big Dig was presented to the public with an estimated cost of agencies 共SHAs兲 around the nation 共Fig. 1兲. A previous project

$2.6 billion 共1982 dollars兲. As it neared completion, it was ex- that supported identification of the factors had included telephone

pected to have a total cost of $14.6 billion 共2002 dollars兲 共Board interviews with all 50 SHAs 共Schexnayder et al. 2003兲. An inter-

on Infrastructure and the Constructed Environment 2003兲. Cost view instrument was prepared and tested initially during onsite

increases trigger disruptions to programs and often downstream

projects have to be delayed or postponed indefinitely to accom-

modate higher construction cost of a single earlier project.

The cost escalation problem is faced by every transportation

agency in the country as projects evolve from a concept in the

long-range planning process, are prioritized for programming, and

are subject to detailed development prior to construction. Project

cost increases, as reflected by budget overruns during the course

of project development, are caused by a number of factors that

have been individually identified through a large number of stud-

ies and research projects. These factors, the causes behind esti-

mate problems and a lack of accuracy, differ with project

development phase and project complexity. Through identifica-

tion of critical cost escalation factors actions can be taken to Fig. 1. State highway agencies interviewed through course of

mitigate the impact of these factors on project and program costs. research

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009 / 223

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

Table 2. Cost Escalation Factors by Cause and Development Phase merous internal factors can lead to underestimation of project

Source Cost escalation factor costs during the planning and design stages of development seven

primary internal factors are well documented: bias, delivery/

Internal • Bias procurement approach, project schedule changes, engineering and

• Delivery/procurement approach construction complexities, scope changes, scope creep, poor esti-

• Project schedule changes mating, and additionally there is the issue of inconsistent appli-

• Engineering and construction complexities cation of contingencies. Cost escalation does not only occur

• Scope changes during the planning and design phases of a project. Project cost

• Scope creep growth often manifests itself during construction. Focusing early

• Poor estimating on internal factors will reduce cost growth at bid time or during

• Inconsistent application of contingencies construction 共Anderson et al. 2006兲. Internal factors that lead to

• Faulty execution the underestimation of project costs during the execution of a

• Ambiguous contract provisions project stem from poor project management and defective design

documents. More specifically, these factors can include inconsis-

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

• Contract document conflicts

External • Local concerns and requirements tent application of contingency, faulty execution, ambiguous con-

• Effects of inflation tract provisions, and contract document conflicts. Each of these

• Scope changes factors separately or in combination with others can cause signifi-

• Scope creep

cant project costs increases over time.

Bias is the demonstrated systematic tendency to be overopti-

• Market conditions

mistic about key project parameters. It is often viewed as the

• Unforeseen events

purposeful underestimation of project costs to ensure a project

• Unforeseen conditions

remains in the construction program. This underestimation of

costs can arise from the estimators’ identification with the agen-

cy’s or firm’s goals for maintaining a construction program. It can

interview with two SHAs. The revised interview instrument was also be the result of pride and a feeling that our agency is smarter

then sent to the SHAs before the interview so that they could than those others that had problems and will not succumb to the

prepare. The interviews were conducted onsite for five SHAs issues of scope changes, scope creep, poor estimating, or any of

through individual interviews and through a group “peer ex- the other factors.

change.” The remaining interviews were conducted by telephone. The project development process for some government agen-

In all cases, the researchers followed the interview protocol to cies is such that the legislature establishes a project budget by

ensure consistency in data collection. The resulting categorization legislative act and that budget is based on preliminary cost esti-

of cost escalation factors can help project owners and engineering mates. Later, if the executing agencies estimate is higher than

professionals focus their attention on the critical issues that lead the budget, the project cannot be let. As a result, engineers and

to cost estimation inaccuracy. agencies feel the pressure to estimate with an optimistic attitude

共Akinci and Fischer 1998; Bruzelius et al. 1998; Condon and

Cost Escalation Factor Classification Harman 2004; Flyvbjerg et al. 2002; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970;

Pickrell 1992兲.

The triangulation analysis considered methodologies from past Delivery/procurement approach effects the division of risk be-

studies and interviews to create a categorization for the causes of tween the agency/owner and the constructors, and when risk is

cost escalation. A better understanding of the cost escalation fac- shifted to a party who is unable to control a specific risk, project

tors is achieved through understanding the forces driving each cost will likely increase. The decision regarding which project

factor or where the factor originates. With this understanding it is delivery approach, 共e.g., design-bid-build, design-build, or build-

possible to design strategies for dealing with these cost escalation operate-transfer兲 and procurement methodology 共e.g., low bid,

factors. best value, or qualifications based selection兲 affects the transfer of

The factors that affect the estimate in each project develop- project risks. In addition to the question of risk allocation, lack of

ment phase are by nature internal and external. Factors that con- experience with a delivery method or procurement approach can

tribute to cost escalation and are controllable by the agency/owner also lead to underestimation of project costs. Many agencies and

are internal, while factors existing outside the direct control of the owners are looking to reduce project schedules to deliver much-

agency/owner are classified as external. This arrangement of fac- needed projects quickly but accelerated schedules are only

tors is shown in Table 2. The presentation order of the factors achievable at a cost. While the end results of applying different

should not be taken as suggesting a level of influence. Table 2 is procurement approaches should be beneficial, some hard lessons

constructed to provide an over arching summary of the factors. It have been learned regarding the proper allocation of risks and

summarizes the factors into logical divisions and classifications what each new contracting method entails, in terms of agency/

and helps in visualizing how project cost estimates are affected. It owner responsiveness, expectations, and time 共Harbuck 2004;

is important to note that one of the factors points to problems with New Jersey Department of Transportation 1999; Parsons Brinck-

estimation of labor and material cost, but most of the factors point erhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. 2002; Science Applications Inter-

to “influences” that impact project scope and timing. national Corporation 2002; Weiss 2000兲.

Project schedule changes, particularly extensions, caused by

budget constraints or design challenges can cause unanticipated

Internal increases in inflation cost effects even when the rate of inflation is

accurately predicted. Agencies/owners must think in terms of the

Internal factors are cost escalation factors that can be directly time value of money and recognize that there are two components

controlled by the project’s sponsoring agency/owner. While nu- to the issue: 共1兲 the inflation rate and 共2兲 the timing of the expen-

224 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

ditures. Many agencies and owners have fixed annual or biannual what is covered by contingency amounts. Contingency funds are

budgets and project schedules must often be adjusted to ensure typically meant to cover a variety of possible events and problems

that project funding is available for all projects as needed. Esti- that are not specifically identified or to account for a lack of

mators frequently do not know what expenditure timing adjust- project definition during the preparation of early planning or pro-

ments will be made 共Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed gramming estimates. Misuse and failure to define what costs con-

Environment 2003; Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/ tingency amounts cover can lead to estimate problems. In many

McGraw-Hill 1995; Callahan 1998; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; cases it is assumed that contingency amounts can be used to cover

GAO 1999; Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al. 1994兲. added scope and planners seem to forget that the purpose of the

Engineering and construction complexities caused by the contingency amount in the estimate is to cover lack of design

project’s location or purpose can make early design work very definition. Agencies and owners run into problems when the con-

challenging and lead to internal coordination problems and tingency amounts are applied inappropriately. Inconsistent appli-

project component errors. Internal coordination problems can in- cation of contingency can be both an internal factor contributing

clude conflicts or problems between the various disciplines in- to underestimation during the planning and preliminary design

volved in the planning and design of a project. Constructability stage and a contributor to cost overruns during final design or

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

problems that need to be addressed may also be encountered as construction phases of the project. During project construction,

the project develops. If these issues are not addressed appropri- contingency funds are inappropriately applied to construction

ately, cost increases are likely to occur 共Board 2003; The Big Dig: overruns and then not available for their intended purpose 共Noor

Key facts about cost, scope, schedule, and management 2003; and Tichacek 2004; Ripley 2004兲.

Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Calla- Faulty execution by an agency/owner in managing a project is

han 1998; GAO 2003; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; GAO 1997, one factor that can lead to project cost overruns. This factor can

1999, 2002; Touran et al. 1994兲. include the inability of the agency’s/owner’s representatives to

Scope changes, which should be controllable by the agent/ make timely decisions or actions, to provide information relative

owner management, can result in underestimation of project to the project, and failure to appreciate construction difficulties

costs. Such changes may include modifications in project con- caused by coordination of connecting work or work responsibili-

struction limits, alterations in design and/or dimensions of key ties 共Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed Environment

project items such as adjustments in type, size, or location of 2003; Callahan 1998; Chang 2002; Touran et al. 1994兲.

project components, as well as other increases in project elements Ambiguous contract provisions dilute responsibility and cause

共Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed Environment 2003; misunderstanding between an owner and project design and con-

Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Calla- struction contractors. Providing too little information in the

han 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck 2004; Hufschmidt and Gerin project documents can lead to cost overruns during the execution

1970; Mackie and Preston 1998; GAO 1999; Merrow 1988; of the project. When the core assumptions underlying an estimate

Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al. 1994兲. are confused by ambiguous contract provisions forecast accuracy

Scope creep is the tendency for the accumulation of many cannot be achieved 共Callahan 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck 2004;

minor scope changes to increase project costs. While individual Mackie and Preston 1998; Touran et al. 1994兲.

scope changes may have only minimal cost impacts, the accumu- Contract document conflicts lead to errors and confusion while

lation of these minor changes, which are often not essential to the bidding and later during project execution they cause change or-

intended function of the facility, can result in a significant cost ders and rework 共Callahan 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck 2004;

increase over time. Many of these minor changes are real needs Mackie and Preston 1998; Touran et al. 1994兲.

that are recognized as more is known about the project but others

are often only nonessential additions. Projects often seem to grow

naturally as the project progresses from inception through design External

development to construction. These changes can often be attrib-

uted to the different needs of the traveling public or environmen- External cost escalation factors are those factors over which the

tal compliance in the area being served 共Akinci and Fischer 1998; agency/owner has little or no direct control over their impact.

Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed Environment 2003; However, the agency/owner needs to consider them when esti-

Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Calla- mating project costs. During the planning and design phase of

han 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck 2004; Hufschmidt and Gerin project development external factors such as local government

1970; Mackie and Preston 1998; GAO 1999; Merrow 1988; concerns and requirements, fluctuations in the rate of inflation,

Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al. 1994兲. scope change, scope creep, and market conditions can lead to

Poor estimating can lead to project cost underestimation. Es- underestimation of project costs. During project construction ex-

timate documentation must be in a form that can be understood, ternal factors such as local government concerns and require-

checked, verified, and corrected. The foundation of a good esti- ments, market conditions, unforeseen events, and unforeseen

mate is the formats, procedures, and processes used to arrive at conditions can be responsible for increases in project cost. The

the cost. Poor estimation includes general errors and omissions possibility of such incidents must be considered during estimate

from plans and quantities as well as general inadequacies and preparation. Again it must be recognized that each of these ele-

poor performance in planning and estimating procedures and ments can act separately or in combination with others to cause

techniques. Errors can be made not only in the volume of material significant project cost increases.

and services needed for project completion but also in the costs of Local concerns and requirements typically include mitigation

acquiring such resources 共Arditi et al. 1985; Booz Allen & Hamil- of project impacts on the surrounding community as well as ne-

ton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Chang 2002; Harbuck gotiated scope changes or additions. Actions by the agency/owner

2004; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Merrow 1988; Pickrell 1992兲. are often required to alleviate perceived negative impacts of con-

Inconsistent application of contingencies causes confusion as struction on the local societal environment as well as the natural

to exactly what is included in the line items of an estimate and environment. Measures may include but are not limited to intro-

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009 / 225

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

ducing changes to project design, alignment, and the conduct of with a single tower. This was a fundamentally different bridge

construction operations. These steps are often taken to appease than the one Caltrans had envisioned resulting in large cost in-

the local residents, business owners, and environmental groups. creases. Agencies have serious estimate inaccuracies when scope

The required accommodation is often unknown during the early changes are imposed externally 共Board on Infrastructure and the

stages of project development. There are a multitude of examples Constructed Environment 2003; Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and

of “drastic” measures that are taken to accommodate local gov- DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Callahan 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck

ernment and citizen concerns as well as national concerns with 2004; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Mackie and Preston 1998;

two of the most notable examples being actions during the GAO 1999; Merrow 1988; Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al.

Legacy Highway project in Utah and the Big Dig in Massachu- 1994兲.

setts. In Utah environment concerns raised by the community Scope creep is similar to changes in scope; however, this is the

played a major role in delaying the project and increasing the effect of the accumulation of multiple minor scope changes.

cost. In Massachusetts the community demanded a signature Projects seem to often grow naturally as the project progresses

bridge across the Charles River. The resulting cable-stayed bridge from inception through development to construction. These

with Y-shaped towers added significantly to the projects cost. changes can often be attributed in the case of transportation and

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Local Concerns and Requirements can affect project costs dur- many other types of projects to the changing needs or growth of

ing the execution phase. Similar to the effects during the planning the population in the area to be served. Minor changes can often

and design phases, mitigation actions imposed by the local gov- occur in response to local agency or citizen requests. 共Akinci and

ernment, neighborhoods, and businesses as well as local and na- Fischer 1998; Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed Envi-

tional environmental groups during the construction of a project ronment 2003; Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-

can extend the project duration affecting inflation allowances or Hill 1995; Callahan 1998; Chang 2002; Harbuck 2004;

add direct cost. By not anticipating these changes, agencies/ Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Mackie and Preston 1998; GAO

owners can be plagued by project cost increases 共Board on Infra- 1999; Merrow 1988; Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al. 1994兲.

structure and the Constructed Environment 2003; Booz Allen & Market conditions or changes in the macro environment can

Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Callahan 1998; affect the costs of a project, particularly large projects. Often only

Chang 2002; Daniels 1998; Harbuck 2004; Hudachko 2004; large contractors or groups of contractors can work or even obtain

“Legacy Parkway: History of the Legacy Parkway.” 2004; bonding for a large project. The size of the project affects com-

Mackie and Preston 1998; GAO 1999; Merrow 1988; Parsons petition for a project and the number of bids that an agency/owner

Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. 2002; Pearl 1994; Sawyer receives for the work. Typically, the risks associated with large

1952; Schroeder 2000; “Summary of independent review commit- projects are much greater, both for the owner and contractor, and

tee findings regarding Woodrow Wilson Bridge superstructure that affects project costs. Inaccurate assessment of the market

contract” 2002; Touran et al. 1992 1994; Woodrow Wilson Bridge conditions can lead to incorrect project cost estimating. Market

project superstrucyure contract 共BR-3兲: Review of the engineer’s conditions affect the project costs during the execution phase

estimate vs. the single bid 2002兲. similar to the effects during the planning phase. Changing market

Effects of inflation is a key factor in the underestimation of conditions during the construction of a project that reduces the

costs for many projects. The time value of money can adversely number of bidders, affects the labor force, and other related ele-

affect projects when 共1兲 project estimates are not communicated ments can disrupt the project schedule and budget 关Board on In-

in year-of-construction costs, 共2兲 project completion is delayed frastructure and the Constructed Environment 2003; Booz Allen

and therefore the cost is subject to inflation over a longer duration & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Callahan 1998;

than anticipated, and/or 共3兲 the rate of inflation is greater than Chang 2002; Mackie and Preston 1998; GAO 1999; Merrow

anticipated in the estimate. Industry has varying views regarding 1988; Pearl 1994; Sawyer 1952; “Summary of independent re-

how inflation should be accounted for in project estimates and in view committee findings regarding the Woodrow Wilson Bridge

budgets. In the case of projects with short development and con- superstructure contract” 2002; Touran et al. 1994; Woodrow Wil-

struction schedules, the effect of inflation is usually minor; how- son Bridge project bridge superstructure contract 共BR-3兲: Review

ever projects having long development and construction durations of the engineer’s estimate vs. the single bid 共2002兲兴.

can encounter unanticipated inflationary effects. The cost esti- Unforeseen events are unanticipated and typically not control-

mates for the Big Dig in Boston are an example of inflation ef- lable by a project owner; these could be occurrences such as

fects. The Big Dig estimate was originally developed in 1982 floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, or other weather related incidents.

based on the Federal Highway Administration guidelines stated in Typically these are called “acts of God.” These acts can bring

the Interstate Cost Estimate manual. The procedures called for the construction to a standstill and have been known to destroy work

exclusion of inflationary factors. Inflation is a large portion of the creating the need for extensive rework or repair. Events controlled

cost overruns experienced on the project 共Akinci and Fischer by third parties that are also unforeseen include terrorism, strikes,

1998; Arditi et al. 1985; Board on Infrastructure and the Con- and changes in financial or commodity markets. These actions can

structed Environment 2003; Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and have devastating results on projects and on project costs 共Akinci

DRI/McGraw-Hill 1995; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Merrow and Fischer 1998; Arditi et al. 1985; Callahan 1998; Chang 2002;

1988; Pickrell 1992; Touran et al. 1994兲. Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Merrow 1988; Semple et al. 1994;

Scope changes, which are not controllable by the owner, can Touran et al. 1994兲.

lead to underestimation of project cost escalation. In California Unforeseen conditions are notorious for causing cost overruns.

the new east span bridge between Oakland and Yerba Buena Is- Unknown soil conditions can effect excavation, compaction, and

land was the responsibility of the California Department of Trans- structure foundations. Contaminated soils may be present. Utili-

portation 共Caltrans兲. The legislation act that funded the bridge ties are often present that are not described or described incor-

placed it under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Transportation rectly on the drawings. There are a multitude of problems that are

Commission 共MTC兲. Based on its rights by jurisdiction the MTC simply unknown during the planning and design phases and

selected an asymmetrical self-anchored suspension bridge design which can increase project cost when they become apparent

226 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

during construction 共Akinci and Fischer 1998; Arditi et al. 1985; an agency’s ability to provide successful projects.

Callahan 1998; Harbuck 2004; Hufschmidt and Gerin 1970; Knowledge of the cost escalation factors that impact project

Merrow 1988; Semple et al. 1994; Touran et al. 1994兲. cost and an awareness of their potential significance is the first

step to mitigation of prospective consequences. Actions may be

taken internally to address the internal cost escalation factors,

State Highway Agency Interviews while communication, education, and engagement of external

sources will aid in managing and anticipating external cost esca-

As part of a larger study to increase consistency and accuracy in lation factors. Proactive measures to limit cost impacts may be

development of cost estimates and management of cost estimates taken to mitigate factors that occur during the planning and de-

from conception to the final engineers estimate the researchers sign phases of project development. For example, risk analysis

identified and categorized cost escalation factors. During this pro- methodologies can be used to identify uncertainties related to

cess the researchers conducted structured interview with over 20 external factors such as potential adverse site conditions. These

SHAs to discuss their cost estimating and cost estimate manage- areas of uncertainty can be translated into risks-related cost im-

pacts and associated contingencies.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

ment processes. During these interviews the SHAs were also

asked about problems and potential weaknesses of their processes One example of a preemptive action to control a cost escala-

and about cost escalation factors. All SHAs reaffirmed the iden- tion factor includes early identification of the project delivery

tified cost escalation factors. Several of the more telling com- system and procurement approach. Late identification of the

ments included: project delivery system or procurement approach can lead to un-

• Loss of experienced staff which leads to new and inexperi- warranted additional costs associated with repletion of work or

enced staff conducting estimate and estimate management ef- application of additional resources that may not have been neces-

forts which can lead to poor estimating. sary with early identification of these project characteristics.

• Environmental agencies typically do not get involved at the There is no silver bullet to achieve better project cost esti-

planning level and the lack of communication at this level can mates. The factors cannot be sorted into a definitive prioritized

influence cost escalation through several factors including en- structure as different factors have a greater affect on specific

gineering and construction complexities, delivery/procurement projects. The factors should be examined on each project indi-

approach, scope changes and scope creep. vidually. Development of thorough estimate documentation and

• The delivery/delivery approach needs to be investigated in approval processes in a cyclical process through project develop-

more detail including increased exploration of combining ment will lead to cost estimate consistency, improved accuracy,

projects. Sometimes projects that have gone through the sys- and better control of scope changes internally. Education and

tem separately end up being combined into one project at let- communication of third parties regarding the cost and schedule

ting. impacts that additions to the projects through scope creep will at

• Higher costs due to local concerns and requirements including least buffer some of the negative press that is experienced on

environmental, historic, and cultural issues, are often encoun- projects that are in the public spotlight.

tered and problems occur in identifying which projects will

experience these issues because of external impacts.

• Projects where the local government has been promoting the

project without detailed designs and once the SHA begins to Conclusions

work on concept development the costs increased substantially

leading to inconsistent application of contingencies. Eighteen cost escalation factors were identified through a com-

• Lack of consistent standards in developing estimates can lead prehensive literature review and verified through intense inter-

to poor estimating. views with over 20 transportation agencies. Identification of these

These are comments from a number of different individuals in cost escalation factors supports efforts to understand the causes of

several SHAs but they are typical of comments made during the project cost escalation. This understanding permits the develop-

interviews. ment of strategies, methods, and tools for better cost estimation

and cost estimating management. Classification of the cost esca-

lation factors empowers estimators, agency/owners, and contrac-

tors to readily identify when specific factors are impacting a

Implications project. Understanding these factors allows for appropriate ac-

tions to mitigate factor impacts. Project participants can take ac-

Singularly or in any combination the identified factors will under- tion to curtail or control the effects of these identified cost

mine a project cost estimate. The outcome of a project, whether escalation factors throughout the life of the project. However,

through cost, schedule, quality or another owner specified mea- “the key to success is to realize and understand the challenges

sure, often determines an owner’s satisfaction with a project. Any early in the planning process, to develop strategies to address

one of the 18 cost escalation factors can taint the project for the them and to establish accurate and achievable expectations”

owner, the designer, and contractor. The constant need to improve 共Capka 2004兲.

the nation’s infrastructure with the limited funds available is the

duty of many agencies. This need stems from the deterioration of

overused systems, requirements for increased safety standards,

and the growing population. Identification and understanding the Acknowledgments

factors that lead to cost escalation on all projects encourages

agencies in their efforts to perform this given duty. However, a The writers express their appreciation to the National Cooperative

deeper understanding of the process and the ability to influence Highway Research Program 共NCHRP兲, Transportation Research

projects in early project development is needed to further enhance Board, under the National Academy of Sciences for sponsoring

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009 / 227

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

this research. Publication of this paper does not necessarily indi- funding grant agreements.” United States General Accounting Office,

cate acceptance by the Academy of its contents, either inferred or GAO/RCED-99–240, 具http://www.gao.gov/archive/1999/rc99240.pdf典

specially expressed herein. The writers also thank the NCHRP 共July 17, 2009兲.

Project 8–49 Panel for their comments and direction during the GAO. 共2002兲. “Transportation infrastructure cost and oversight issues on

major highway and bridge projects.” GAO-02–702T, Washington,

research process. Additionally, the writers thank the state highway

D.C., May 1.

agency personnel who supported this research through their time

GAO. 共2003兲. “Federal-aid highways cost and oversight of major high-

and effort, without their valuable contributions this research way and bridge project—Issues and options.” GAO-03–764T, Wash-

would not have been possible. ington, D.C., May 8.

Harbuck, R.H. 共2004兲. “Competitive Bidding for Highway Construction

Projects.” 2004 Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering

References International Transactions, Association for the Advancement of Cost

Engineering International, Morgantown, W.Va.

“$3,200,000 more asked for tunnel.” 共1926兲. New York Times, New York, Hudachko, T. 共2004兲. “Legacy Parkway SEIS moving forward.” Shared

solutions, Vol. 2, Utah Transportation Authority and Utah Dept. of

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

February 10, 2.

Akinci, B., and Fischer, M. 共1998兲. “Factors affecting contractors’ risk of Transportation, Salt Lake City, Utah.

cost overburden.” J. Manage. Eng., 14共1兲, 67–76. “Hudson vehicle tube.” 共1919兲. New York Times, New York, February 25,

Anderson, S., Molenaar, K., and Schexnayder, C. 共2006兲. National Co- 11.

operative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Web-Only Document Hufschmidt, M. M., and Gerin, J. 共1970兲. “Systematic errors in cost es-

98: Final Report for NCHRP Report 574: Guidance for Cost Estima- timates for public investment projects.” The analysis of public output,

tion and Management for Highway Projects During Planning, Pro- J. Margolis, ed., Columbia, New York.

gramming, and Preconstruction, National Cooperative Highway “Legacy Parkway: History of the Legacy Parkway.” 共2004兲. 具http://

Research Program and Transportation Research Board, 具http:// www.legacyinfo.com/overview/典 共August 12, 2004兲.

onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_w98.pdf典 共Jun. 30, 2007兲. Mackie, P., and Preston, J. 共1998兲. “Twenty-one sources of error and bias

Arditi, D., Tarim Akan, G., and Gurdamar, S. 共1985兲. “Cost overruns in in transportation project appraisal.” Transport policy 5, Institute for

public projects.” Journal of Project Management, Vol. 3, No. 4, But- Transport Studies, Univ. of Leeds, U.K., 1–7.

terworth & Co. Ltd., London, 218–224. Merrow, E. W. 共1988兲. Understanding the outcomes of mega projects: A

“Asks $28,669,000 for Jersey tube.” 共1920兲. New York Times, New York, quantitative analysis of very large civilian projects, Rand, Santa

February 15, 17. Monica, Calif.

“Ask nation to share in tunnel to Jersey.” 共1918兲. New York Times, New “Name interstate tunnel engineers.” 共1919兲. New York Times, New York,

York, June 29, 15. June 15, 28.

The Big Dig: Key facts about cost, scope, schedule, and management. New Jersey Dept. of Transportation. 共1999兲. “New Jersey’s modified

共2003兲. Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff. design/build program.” Progress Rep. No. 6, Department of Transpor-

Board on Infrastructure and the Constructed Environment. 共2003兲. Com- tation, N.J.

pleting the “Big Dig”: Managing the final stages of Boston’s central Noor, I., Tichacek, R.L. 共2004兲. “Contingency misuse and other risk man-

artery/tunnel project, National Academy of Engineering, Washington, agement pitfalls.” 2004 Association for the Advancement of Cost En-

D.C., National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. gineering International Transactions, Association for the

Booz Allen & Hamilton Inc. and DRI/McGraw-Hill. 共1995兲. “The transit Advancement of Cost Engineering International, Morgantown, W.Va.

capital cost index study.” Federal Transit Administration, 具http:// Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. 共2002兲. Final draft: Design-

www.fta.dot.gov/publications/reports/other_reports/publications_ build practice report, New York State Dept. of Transportation, Al-

4873.html典 共July 17, 2009兲. bany, New York.

Bruzelius, N., Flyvbjerg, B., and Rothergatter, W. 共1998兲. “Big decisions, Pearl, R. 共1994兲. “The effect of market conditions on tendering and fore-

big risk: Improving accountability in mega projects.” Int. Rev. Adm. casting.” 1994 Association for the Advancement of Civil Engineering

Sci., 64, 423–440. International Transactions, Association for the Advancement of Cost

Callahan, J. T. 共1998兲. Managing transit construction contract claims, Engineering International, Morgantown, W.Va.

Transportation Research Board, Transportation cooperative research Pickrell, D. H. 共1992兲. “A desire named streetcar: Fantasy and fact in rail

program synthesis 28, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., transit promotions and evaluation.” J. Am. Plann. Assoc., 58共2兲, 158–

1–59. 176.

Capka, J. R. 共2004兲. “Megaprojects—They are a different breed.” Public Ripley, P.W. 共2004兲. “Contingency! Who owns and manages it!” 2004

Roads, 68共1兲, 具http://www.tfhrc.gov/pubrds/04jul/01.htm典 共July 17, Association for the Advancement of Civil Engineering International

2009兲. Transactions, Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering

Chang, A. S. 共2002兲. “Reasons for cost and schedule increases for engi- International, Morgantown, W.Va.

neering design projects.” J. Manage. Eng., 18共1兲, 29–36. Sawyer, J. E. 共1952兲. “Entrepreneurial error and economic growth.” Ex-

Condon, E., Harman, F. 共2004兲. “Playing games.” 2004 Association for plorations in Entrepreneurial History, 4共4兲, 199–204.

the Advancement of Cost Engineering International Transactions, As- Schexnayder, C. J., Weber, S. L., and Fiori, C. 共2003兲. “Project cost

sociation for the Advancement of Cost Engineering International, estimating a synthesis of highway practice.” NCHRP Project 20–07/

Morgantown, W.Va. Task 152 Rep., Transportation Research Board, National Research

Daniels, B. 共1998兲. “A legacy of conflict: Utah’s growth and the legacy Council, Washington, D.C.

highway.” Hinckly J. Polit, 1, 51–60. Schroeder, D. V. 共2000兲. “Comments on Legacy Parkway FEIS and 404

“Megaprojects need more study up front to avoid cost overruns.” 共2002兲. Permit Application.” Ogden Group Sierra Club, 具http://

Enginering News Record, McGraw-Hill. www.utah.sierraclub.org/ogden/legacycom.html典 共Aug. 12, 2004兲.

Flyvbjerg, B., Holm, M. K. S., Buhl, S. L. 共2002兲. “Underestimating costs Science Applications International Corporation. 共2002兲. “2002 Survey by

in public works projects: Error or lie?” J. Am. Plan. Assn., 68共3兲, SAIC for Illinois DOT on the current use of design-build.” Federal

279–295. Highway Administration, 具http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/programadmin/

GAO. 共1997兲. “Transportation infrastructure managing the costs of large- contraacts/survey02.htm典 共February 19, 2002兲.

dollar highway projects.” GAO/RCED-97–47, Washington, D.C., Feb- Semple, C., Hartman, F. T., and Jergeas, G. 共1994兲. “Construction claims

ruary. and disputes: Causes and cost/time overruns.” J. Constr. Eng. Man-

GAO. 共1999兲. “Mass transit: Status of new starts transit projects with full age., 120共4兲, 785–795.

228 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009

J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

Sinnette, J. 共2004兲. “Accounting for megaproject dollars, public roads.” “Vehicular tunnel cost up $14,000,000.” 共1924兲. New York Times, New

Federal Highway Administration, 68共1兲, July/August, 具http:www. York, January 15, 23.

tfhrc.gov/pubrds/04jul/07.htm典 共Nov. 11, 2004兲. “Way all cleared for Jersey tunnel.” 共1921兲. New York Times, New York,

Summary of independent review committee findings regarding the Wood-

December 28, 4.

row Wilson Bridge superstructure contract. 共2002兲. March 1.

Touran, A., Bolster, P. J., and Thayer, S. W. 共1994兲. “Risk assessment in Weiss, L.L. 共2000兲. Design/build—Lessons learned to date, South Dakota

fixed guideway transit system construction.” Federal Transit Admin- Dept. of Transportation, Pierre, S.D.

istration and U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C. Woodrow Wilson Bridge project bridge superstructure contract (BR-3):

“Urges new tunnel under the Hudson.” 共1918兲. New York Times, New Review of the engineer’s estimate vs. the single bid. 共2002兲. February

York, March 18, 18. 28.

“Vehicular tube is growing.” 共1923兲. New York Times, New York, July 1, “Work on tunnel began 7 years ago.” 共1927兲. New York Times, New York,

1. November 13, 26.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by Iowa State University on 10/21/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / OCTOBER 2009 / 229

View publication stats J. Manage. Eng., 2009, 25(4): 221-229

Вам также может понравиться

- Project ControPROJl For Construction CII P6 - 5Документ52 страницыProject ControPROJl For Construction CII P6 - 5plannersuper100% (1)

- MSC BSE Course Guide 13 - 14 PDFДокумент0 страницMSC BSE Course Guide 13 - 14 PDFKamran KhanОценок пока нет

- A201-2007 - General Conditions of The Contract For Construction - 001Документ36 страницA201-2007 - General Conditions of The Contract For Construction - 001Maram SabaОценок пока нет

- eRep-BOMA BESt Assessment - Light Industrial PropertiesДокумент34 страницыeRep-BOMA BESt Assessment - Light Industrial PropertiesJurizal Julian LuthanОценок пока нет

- 4 Feasibility PDFДокумент27 страниц4 Feasibility PDFMuneeb ur rehman ansariОценок пока нет

- Chapter 7Документ132 страницыChapter 7Vyrka Dinda MaurerОценок пока нет

- A Survey of Transferable Development Rights Mechanisms in New York City ResearchДокумент55 страницA Survey of Transferable Development Rights Mechanisms in New York City ResearchcrainsnewyorkОценок пока нет

- Annex 1 - Feasibility StudyДокумент186 страницAnnex 1 - Feasibility Studynicu_boevicuОценок пока нет

- Intelligent Building Automation Systems A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionОт EverandIntelligent Building Automation Systems A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionОценок пока нет

- NATSPEC BIM Object-Element Matrix v1.0 Sep 2011Документ96 страницNATSPEC BIM Object-Element Matrix v1.0 Sep 2011abc321987Оценок пока нет

- CHP Feasibility Software PackagesДокумент7 страницCHP Feasibility Software PackagessunatrutgersОценок пока нет

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Li-Yin Shen, Vivian W.Y. Tam, Leona Tam, Ying-Bo JiДокумент6 страницJournal of Cleaner Production: Li-Yin Shen, Vivian W.Y. Tam, Leona Tam, Ying-Bo JiNhan DoОценок пока нет

- API Valn StandardsДокумент406 страницAPI Valn StandardsChengОценок пока нет

- Condocs Numbering SystemДокумент0 страницCondocs Numbering SystemEhtisham HaiderОценок пока нет

- Integrated Technology 1 ProjectДокумент9 страницIntegrated Technology 1 ProjectSeno Aditya PutraОценок пока нет

- Cost Estimation TechniquesДокумент26 страницCost Estimation TechniquesKentDemeterioОценок пока нет

- Sales and Distribution ManagementДокумент86 страницSales and Distribution ManagementJaja Goles SabanalОценок пока нет

- Feasibility Study Template CH 12Документ4 страницыFeasibility Study Template CH 12tausarpaoОценок пока нет

- 5.a Cons RFP Icb Section 6 - TorДокумент68 страниц5.a Cons RFP Icb Section 6 - TorFОценок пока нет

- N - Technical Spec. 110 Rev. E (IFP) - 110-2009-19Документ273 страницыN - Technical Spec. 110 Rev. E (IFP) - 110-2009-19bbhattОценок пока нет

- Akac 2021Документ1 157 страницAkac 2021J MОценок пока нет

- Distribution Channel Management - AnДокумент36 страницDistribution Channel Management - AnSunil DasОценок пока нет

- Contract Change Order No. 12 RedactedДокумент12 страницContract Change Order No. 12 RedactedL. A. PatersonОценок пока нет

- 17 - Appendix 4 UNSW Drafting Standards July 2015Документ15 страниц17 - Appendix 4 UNSW Drafting Standards July 2015Stefan PalaghiaОценок пока нет

- Kenya Power Sector ReportДокумент19 страницKenya Power Sector ReportManuel CooperОценок пока нет

- Value Chain Management-Group 1Документ64 страницыValue Chain Management-Group 1jenice joyОценок пока нет

- Electrical Power Supply and DistributionДокумент127 страницElectrical Power Supply and DistributionSuresh KumarОценок пока нет

- Cost Estimation Electrical WorksДокумент26 страницCost Estimation Electrical WorksAli AlakhrasОценок пока нет

- MBO ProfileДокумент50 страницMBO ProfileimansaripkОценок пока нет

- 15421-PM-FSP-0002 Rev A Principal Project Requirements PDFДокумент99 страниц15421-PM-FSP-0002 Rev A Principal Project Requirements PDFgemilanglpОценок пока нет

- ILP Note On Obtrusive LightingДокумент15 страницILP Note On Obtrusive LightinganasmuhdОценок пока нет

- Toyota PresentationДокумент12 страницToyota PresentationShanoonОценок пока нет

- ResumeДокумент4 страницыResumeapi-19608934Оценок пока нет

- Benefits of Using Mobile Transformers and Mobile Substations (MTS - Report - To - Congress - FINAL - 73106)Документ48 страницBenefits of Using Mobile Transformers and Mobile Substations (MTS - Report - To - Congress - FINAL - 73106)Arianna IsabelleОценок пока нет

- Power Fuse SM 5Документ19 страницPower Fuse SM 5ferdinandz_010Оценок пока нет

- Item Code DevelopersДокумент41 страницаItem Code DeveloperszakazОценок пока нет

- FIFA Stadiumbook2011 - Lighting PDFДокумент28 страницFIFA Stadiumbook2011 - Lighting PDFLiviu PetreusОценок пока нет

- WACC Presentation UQДокумент42 страницыWACC Presentation UQDaniyaNaiduОценок пока нет

- Design Studio Reverberation Time CalculationsДокумент15 страницDesign Studio Reverberation Time CalculationsBlessing MukomeОценок пока нет

- Domestic Exterior Lighting: Getting It Right!: Guidance Note 9/19Документ6 страницDomestic Exterior Lighting: Getting It Right!: Guidance Note 9/19dkshtdkОценок пока нет

- Green Building RoadmapДокумент4 страницыGreen Building RoadmapcrainsnewyorkОценок пока нет

- ReGreen GuidelinesДокумент182 страницыReGreen GuidelinesDavid Yates100% (5)

- Polymax Accoustic Design GuideДокумент11 страницPolymax Accoustic Design GuidempwasaОценок пока нет

- State of The Art Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)Документ14 страницState of The Art Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)varun.119100% (1)

- Strategy and Project ManagementДокумент17 страницStrategy and Project ManagementMARHEWОценок пока нет

- CC2 in-SOL-160 Business and Solution Requirements - GCR10443 Freight Auto-Netting v1.0Документ16 страницCC2 in-SOL-160 Business and Solution Requirements - GCR10443 Freight Auto-Netting v1.0Ramki PОценок пока нет

- Method of MeasurementДокумент35 страницMethod of MeasurementAlexОценок пока нет

- BCSA Financial Handbook - Secured Final V2Документ0 страницBCSA Financial Handbook - Secured Final V2Difa LiuОценок пока нет

- 021 1700 023e 11e - MarineДокумент56 страниц021 1700 023e 11e - Marine김남균Оценок пока нет

- Blackbook TybmsДокумент68 страницBlackbook TybmsTonu PawarОценок пока нет

- OC IET Fellowship-Criteria v4Документ2 страницыOC IET Fellowship-Criteria v4anji201Оценок пока нет

- NEC Document For Recloser ServicesДокумент40 страницNEC Document For Recloser ServiceshbaocrОценок пока нет

- Energy Management in Public Sector Buildings Manual May 2015 PDFДокумент61 страницаEnergy Management in Public Sector Buildings Manual May 2015 PDFzukchuОценок пока нет

- Harmonic Quality in Naval ShipsДокумент6 страницHarmonic Quality in Naval Shipstkdrt2166Оценок пока нет

- StandardsДокумент74 страницыStandardsFlo Mirca0% (1)

- Criteria For Construction Project Success A Literature ReviewДокумент21 страницаCriteria For Construction Project Success A Literature ReviewJuan AlayoОценок пока нет

- Statutory Interpretation: Theories, Tools, and Trends: Valerie C. BrannonДокумент67 страницStatutory Interpretation: Theories, Tools, and Trends: Valerie C. BrannonMarjo PachecoОценок пока нет

- FinalPaper PMJДокумент16 страницFinalPaper PMJAnita GutierrezОценок пока нет

- Improving Project Budget Estimation Accuracy and Precision by Analyzing Reserves For Both Identified and Unidentified Risks PDFДокумент16 страницImproving Project Budget Estimation Accuracy and Precision by Analyzing Reserves For Both Identified and Unidentified Risks PDFPavlos MetallinosОценок пока нет

- IJSRCE23734Документ7 страницIJSRCE23734Thushara BandaraОценок пока нет

- 2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Документ102 страницы2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Veah LimОценок пока нет

- ConstructionProjectCostEscalationFactors PDFДокумент10 страницConstructionProjectCostEscalationFactors PDFhfenangadОценок пока нет

- ConstructionProjectCostEscalationFactors PDFДокумент10 страницConstructionProjectCostEscalationFactors PDFhfenangadОценок пока нет

- Attachment - Costing FlowchartДокумент1 страницаAttachment - Costing FlowcharthfenangadОценок пока нет

- Citation 315732691Документ1 страницаCitation 315732691hfenangadОценок пока нет

- Off-Grid Wind Power Bill of QuantityДокумент3 страницыOff-Grid Wind Power Bill of QuantityericmuyaОценок пока нет

- Offshore Wind Farm ProjectДокумент39 страницOffshore Wind Farm ProjectAlireza Aleali89% (9)

- 2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Документ102 страницы2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Veah LimОценок пока нет

- Costs RevisedДокумент23 страницыCosts RevisedhfenangadОценок пока нет

- Unit Cost Database (v.1.4) - IntroductionДокумент51 страницаUnit Cost Database (v.1.4) - IntroductionhfenangadОценок пока нет

- 2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Документ102 страницы2 Magsaysay Bridge - Technical Specifications - Section B Special Provisions - Rev 2 - April 2019Veah LimОценок пока нет

- 2019 BCCD TocДокумент7 страниц2019 BCCD Tochfenangad0% (11)

- Sustainability 12 00905 v2Документ20 страницSustainability 12 00905 v2hfenangadОценок пока нет

- UPLEXCELДокумент13 страницUPLEXCELhfenangadОценок пока нет

- Using BPN Method For Estimating Cement Take of Grouting: ValueДокумент9 страницUsing BPN Method For Estimating Cement Take of Grouting: ValuehfenangadОценок пока нет

- Unit Cost Database (v.1.4) - IntroductionДокумент51 страницаUnit Cost Database (v.1.4) - IntroductionhfenangadОценок пока нет

- Concrete Brochure 2015Документ8 страницConcrete Brochure 2015hfenangadОценок пока нет

- Puerto Princesa Airport Updated FS Vol II Part4Документ144 страницыPuerto Princesa Airport Updated FS Vol II Part4Edna CruzОценок пока нет

- Architect's Cost EstimateДокумент27 страницArchitect's Cost EstimateNoel Malinao Cablinda0% (1)

- 2017 Cost Data Book PDFДокумент533 страницы2017 Cost Data Book PDFhfenangad50% (2)

- Economic Analysis Water Supply ProjectsДокумент29 страницEconomic Analysis Water Supply ProjectskumarsathishsОценок пока нет

- Countdown Timers For Powerpoint: Produced by Dave FoordДокумент36 страницCountdown Timers For Powerpoint: Produced by Dave FoordvidyatomОценок пока нет

- SureFlowEquipmentInc US Price List Sept2012Документ32 страницыSureFlowEquipmentInc US Price List Sept2012mihailspiridonОценок пока нет

- Handbook Foundation Form Work Rebar ConcreteДокумент216 страницHandbook Foundation Form Work Rebar ConcretebittuchintuОценок пока нет

- CSRA Sample RiskReportДокумент15 страницCSRA Sample RiskReportArturo RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Small Hydro AnalysisДокумент52 страницыSmall Hydro Analysisapi-26947710100% (2)

- Bird Consturction Company Employment Contract Letter CbsaДокумент5 страницBird Consturction Company Employment Contract Letter CbsahfenangadОценок пока нет

- Santonia Energy Inc. Candidate Questionnaire Online Interview Form 2014.Документ5 страницSantonia Energy Inc. Candidate Questionnaire Online Interview Form 2014.hfenangadОценок пока нет

- B. Spuida - Technical Writing Made EasierДокумент17 страницB. Spuida - Technical Writing Made EasieraeloysОценок пока нет

- Juliana Demoraes ResumeДокумент1 страницаJuliana Demoraes ResumejulianaОценок пока нет

- Amery Hill School Newsletter July 2016Документ24 страницыAmery Hill School Newsletter July 2016boredokОценок пока нет

- Cloud - The Future of The IT DepartmentДокумент12 страницCloud - The Future of The IT DepartmentdimastriОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 - Principles of Management Notes PDFДокумент13 страницChapter 2 - Principles of Management Notes PDFtushar kandpalОценок пока нет

- CIR V. Asalus Corp.Документ10 страницCIR V. Asalus Corp.Rene ValentosОценок пока нет

- Nalanda International School: Vadodara, IndiaДокумент15 страницNalanda International School: Vadodara, IndiaToshika AgrawalОценок пока нет

- ARCHIGRAMДокумент9 страницARCHIGRAMIndraja RmОценок пока нет

- JULY 2021: Sss Number Surname Given Name Social Security System TotalДокумент5 страницJULY 2021: Sss Number Surname Given Name Social Security System TotalRhona San JuanОценок пока нет

- Ariza Research Change Identity 2014Документ398 страницAriza Research Change Identity 2014akshayinbox86% (7)

- The Implications of Heterogeneous Sectioning in Academic Performance of Grade 10 Students in Morong National High SchoolДокумент10 страницThe Implications of Heterogeneous Sectioning in Academic Performance of Grade 10 Students in Morong National High SchoolGuest457Оценок пока нет

- Fir, It' S Objective and Effect of Delay in Fir Shudhanshu RanjanДокумент7 страницFir, It' S Objective and Effect of Delay in Fir Shudhanshu RanjanPrerak RajОценок пока нет

- GCE Computer Science: Unit H046/01: Computing Principles Advanced Subsidiary GCEДокумент18 страницGCE Computer Science: Unit H046/01: Computing Principles Advanced Subsidiary GCEfatehsalehОценок пока нет

- B1562412319 PDFДокумент202 страницыB1562412319 PDFAnanthu KGОценок пока нет

- Reflection About The Rights and Privileges of Teachers in 1987 Philippine Constitution and Magna Carta For Public SchoolДокумент2 страницыReflection About The Rights and Privileges of Teachers in 1987 Philippine Constitution and Magna Carta For Public SchoolPaulene Arcan83% (6)

- Dublin Airport Central BrochureДокумент38 страницDublin Airport Central BrochureAriel ArcillaОценок пока нет

- Sweden: Employment Law Overview 2021-2022Документ28 страницSweden: Employment Law Overview 2021-2022Zelda Craig-TobinОценок пока нет

- Understanding The Self Activity 4Документ2 страницыUnderstanding The Self Activity 4Asteria GojoОценок пока нет

- San Beda CurriculumДокумент2 страницыSan Beda CurriculumMark YoungbastardОценок пока нет

- Fishing Industry PDFДокумент25 страницFishing Industry PDFYusra AhmedОценок пока нет

- Landscape of The SoulДокумент2 страницыLandscape of The SoulsdrgrОценок пока нет

- Highway and Railroad EngineeringДокумент27 страницHighway and Railroad EngineeringFrancis Ko Badongen-Cawi Tabaniag Jr.Оценок пока нет

- 1st ContemporaryДокумент29 страниц1st ContemporaryLeah Jean VillegasОценок пока нет

- Filipino Images of The NationДокумент26 страницFilipino Images of The NationLuisa ElagoОценок пока нет

- Thesis ProposalДокумент55 страницThesis ProposalSheryl Tubino EstacioОценок пока нет

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictДокумент5 страниц(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowОценок пока нет

- KR-G12 GSM Alarm System Instruction User GuideДокумент21 страницаKR-G12 GSM Alarm System Instruction User GuideFernando SОценок пока нет

- Using Data To Drive OTIF and Retail Compliance SuccessДокумент26 страницUsing Data To Drive OTIF and Retail Compliance SuccessShivshankar HondeОценок пока нет

- Suara TEEAM 82nd Issue E-NewsletterДокумент92 страницыSuara TEEAM 82nd Issue E-NewsletterTan Bak PingОценок пока нет

- IELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayДокумент2 страницыIELTS Writing Task 2/ IELTS EssayOlya HerasiyОценок пока нет

- Camarilla City StructureДокумент1 страницаCamarilla City StructureVassilis TsipopoulosОценок пока нет