Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Labor Relations - Appeals, Rules, Bond

Загружено:

Stef MacapagalАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Labor Relations - Appeals, Rules, Bond

Загружено:

Stef MacapagalАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

APPEALS, RULES, BOND

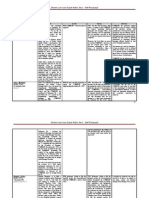

Aklan College v. Enero

FACTS: Perpetuo Enero, Arlyn Castigador, Nuena Sermon, and Jocelyn Zolina were high school teachers

employed by Aklan College. When high school students of the college handled by the said teachers held mass

actions against the principal of the high school department, the teachers were dismissed after an

administrative investigation. They filed a complaint for illegal dismissal against the school with the LA, and

the LA ruled in their favor, stating that they had indeed been illegally dismissed, and granting them

reinstatement, backwages, 13th month pay, service incentive leave pay, and moral and exemplary damages.

On appeal, the NLRC reversed the LA decision, stating that the teachers’ dismissal was valid. However, the

NLRC ordered Aklan College to pay the teachers their 13 th month pay and service incentive leave pay. Both

parties filed a motion for reconsideration, but the NLRC denied both motions for lack of merit.

Aklan College filed a petition for certiorari before the CA, seeking to partially annul the NLRC

decision insofar as it held the school liable for the payment of the dismissed teachers’ 13 th month pay and

service incentive leave pay despite the finding that they were illegally dismissed from service. The teachers

did not anymore file an appeal from the NLRC decision. The CA held that the NLRC did not commit grave

abuse of discretion in awarding the teachers 13th month pay and service incentive leave pay. However, it

modified the award to conform to the dismissed teachers’ employment history, thus even increasing the

amount awarded to each of the dismissed teachers. Aklan College appeals the CA decision.

ISSUE: W/N the CA committed grievous error when it increased the monetary awards of 13 th month pay and

service incentive leave pay in favor of the non-appealing private respondents.

NO. As a rule, a party who does not appeal from the decision may not obtain any affirmative relief from the

appellate court other than what he has obtained from the lower tribunal, if any, whose decision is brought up

on appeal. Due process prevents the grant of additional awards to parties who did not appeal. As an

exception, he may assign an error where the purpose is to maintain the judgment on other grounds, but he

cannot seek modification or reversal of the judgment or affirmative relief unless he has also appealed or filed

a separate petition. In this case, the CA is not precluded from affirming, reversing, or modifying the propriety

of payment of the 13th month pay and service incentive leave pay to the respondents. It is the propriety of the

award of these benefits which were precisely the issues raised by Aklan College in its appeal before the said

appellate court. By way of exception, the CA may reverse the decision of the lower tribunal on the basis of

grounds other than those raised on appeal in the following instances:

(1) Grounds not assigned as errors but affecting jurisdiction over the subject matter;

(2) Matters not assigned as errors on appeal but are evidently plain or clerical errors within

contemplation of law;

(3) Matters not assigned as errors on appeal but consideration of which is necessary in arriving at a just

decision and complete resolution of the case or to serve the interest of justice or to avoid dispensing

piecemeal justice;

(4) Matters not specifically assigned as errors on appeal but raised in the trial court and are matters of

record having some bearing on the issue submitted which the parties failed to raise or which the

lower court ignored;

(5) Matters not assigned as errors on appeal but closely related to an error assigned; and

(6) Matters not assigned as errors on appeal but upon which the determination of a question properly

assigned, is dependent.

1|S. Macapagal. BSU LAW 2012

The CA committed no reversible error in increasing the amounts of the 13 th month pay and the service

incentive leave pay in order to correct the error committed by the NLRC in the computation. The instant

controversy falls squarely under the third exception enumerated above. A just, fair, and complete resolution

of the case necessarily entails the correct computation of these benefits. To avoid dispensing piecemeal

justice, the full period of employment of respondents was rightfully considered by the CA in the computation

of the 13th month pay and the service incentive leave pay. The procedural lapse on the part of the NLRC in this

case in failing to take into account the number of years when the private respondents did not receive their

13th month and service incentive leave pay cannot defeat their right to receive these benefits as granted under

substantive law. The Supreme Court simply could not uphold an erroneous computation of the said unpaid

benefits. Hence, it had to re-compute, and, as a consequence, increased it.

Petition denied. CA decision affirmed.

It does not follow that since the employer is not guilty of illegal dismissal, then he is not liable for

non-payment of 13th month pay and service incentive leave pay. Illegal dismissal and non-payment of

benefits are entirely different grounds on which an employer can be held liable.

Tacloban Far East Marketing v. CA

FACTS: Benjamin Sabulao was hired by Tacloban Far East Marketing Corp. as a helper in its hardware

business, then as delivery truck driver. Sometime in May 2001, Sabulao allegedly asked permission to absent

himself for five days because of his grandfather’s death. When he reported back to work, he was informed

that he cannot work there anymore.

In August 2001, Sabulao filed before the LA a complaint for illegal dismissal and money claims

against Tacloban. The LA ruled in favor of Tacloban, finding that Sabulao had abandoned his work and as

such, his dismissal was valid. At the same time, Tacloban was ordered to pay Sabulao his salary differentials

and service incentive leave pay. The other money claims were denied for failure to substantiate the same. On

appeal, the NLRC reversed the LA, ruling that Sabulao had been illegally dismissed, and ordering Tacloban to

pay Sabulao his backwages and separation pay, salary differentials, and service incentive leave pay. Tacloban

filed a petition for certiorari with the CA, which merely affirmed the decision of the NLRC. Tacloban then

appealed to the SC by way of petition for review on certiorari, two months after the receipt of the decision of

the CA denying its petition.

ISSUE: W/N Tacloban was able to file a timely appeal.

NO. At the outset, it must be stated that Tacloban adopted the wrong mode of remedy in bringing the case

before the SC. It is well-settled that the proper recourse of an aggrieved party to assail the decision of the CA

is to file a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court. The Rules preclude recourse to

the special civil action of certiorari if appeal, by way of a petition for review is available, as the remedies of

appeal and certiorari are mutually exclusive and not alternative or successive. Certiorari cannot be used as a

substitute for a lost appeal. Though there are instances when certiorari was granted despite the availability of

appeal, none of these recognized exceptions was shown to be present in the case at bar. Moreover, while it is

true that the Court may treat a petition for certiorari as having been filed under Rule 45 in the interest of

substantial justice, the present petition could not be given the same leniency because it was filed beyond the

15-day reglementary period within which to file a petition for review on certiorari. The records show that the

petitioners, instead of filing a petition for review on certiorari within 15 days of their receipt of the CA

Resolution denying their petition, they waited for two months before filing the instant petition. Accordingly,

2|S. Macapagal. BSU LAW 2012

the decision of the CA had already become final and executory and beyond the purview of the SC to act upon.

The inescapable conclusion is that the present petition was filed belatedly to make up for a lost appeal.

Petition denied for lack of merit. CA decision affirmed.

In termination cases, the burden of proof rests upon the employer to show that the dismissal was for

a just and valid cause and failure to discharge the same would mean that the dismissal is not justified

and therefore illegal.

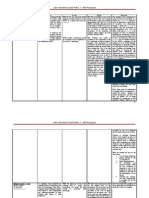

McBurnie v. Ganzon

FACTS: Andrew James McBurnie, an Australian national, signed a five-year employment contract as executive

vice president of EGI in May 1999. In November of the same year, he featured in an accident that fractured his

skull and necessitated his confinement at the Makati Medical Center. While recuperating from his injuries in

Australia, he was informed by EGI’s president that his services were no longer needed since the project he

had been hired to work on had been permanently discontinued. In October 2002, McBurnie filed a complaint

for illegal dismissal with prayer for the payment of his salary and benefits under the unexpired term of the

contract, damages, and attorney’s fees. The LA ruled in his favor, declaring his dismissal to be illegal and

ordering EGI to pay his salary and benefits for the unexpired term of the contract amounting to $985,162.00,

as well as moral and exemplary damages amounting to P2M, and attorney’s fees equivalent to 10% of the

total monetary award. Ten days after EGI received the LA’s decision, it filed a memorandum of appeal with

the NLRC and Motion to Reduce Bond, and posted the amount of P100,000.00, arguing that the awards of the

LA were null and excessive, with the premeditated intention to render the employer incapable of posting an

appeal bond and consequently deprive him of the right to appeal. The NLRC subsequently denied the motion

to reduce bond and ordered EGI to post an additional bond of P54M together with the other requirements

under Section 6, Rule VI of the NLRC Rules of Procedure within a non-extendible period of 10 days from

receipt thereof, otherwise the appeal shall be dismissed. Instead of complying with the NLRC order, EGI filed a

petition for certiorari and prohibition with the CA with prayer for issuance of a preliminary injunction and/or

temporary restraining order. A 60-day TRO was issued by the CA. However, upon the expiration of the 60-day

TRO, and EGI still failed to post additional bond, the NLRC dismissed EGI’s appeal. EGI again filed with the CA

a petition for certiorari with prayer for the issuance of a TRO and/or writ of preliminary injunction, which

was granted. The CA then issued a writ of preliminary injunction after EGI posted an injunction bond of

P10M. McBurnie assails the issuance of the writ before the SC, but was dismissed for submitting an affidavit

of service which failed to show a competent evidence of the affiant’s identity. The CA then granted EGI’s

Motion to Reduce Bond and directed it to post an appeal bond of P10M with the NLRC, which was likewise

ordered to give due course to the appeal and to conduct further proceedings. McBurnie appealed to the SC.

ISSUE 1:W/N the CA committed grave abuse of discretion by lowering the amount of bond to be posted by

EGI in the course of its appeal.

YES. While the bond may be reduced upon motion by the employer, this is subject to the conditions that (1)

the motion to reduce bond shall be on meritorious grounds; and (2) a reasonable amount in relation to the

monetary award is posted by the appellant, otherwise the filing of the motion to reduce bond shall not stop

the running of the period to perfect an appeal. The qualification effectively requires that unless the NLRC

grants the reduction of cash bond within the 10-day reglementary period, the employer is still expected to

post the cash or surety bond securing the full amount within the said 10-day period. If the NLRC does

eventually grant the motion for reduction after the reglementary period has elapsed, the correct relief would

be to reduce the cash or surety bond already posted by the employer within the 10-day period. Records show

that EGI filed their Memorandum of Appeal and Motion to Reduce Appeal Bond on the 10 th or last day of the

3|S. Macapagal. BSU LAW 2012

reglementary period. Although they posted an initial appeal bond of P100,000.00, the same was grossly

inadequate compared to the monetary awards given by the LA. Further, there is no basis in EGI’s contention

that the LA’s awards were null and excessive, and with premeditated intention to render EGI incapable of

posting an appeal bond and deprive them of the right to appeal. Moreover, the cash/surety bond requirement

does not necessitate the employer to physically surrender the entire amount of the monetary judgment. The

usual procedure is for the employer to obtain the services of a bonding company, which will then require the

employer to pay a percentage of the award in exchange for a bond securing the full amount. This observation

undercuts the notion of financial hardship as a justification for the inability to timely post the required bond.

The posting of a bond is indispensable to the perfection of an appeal in cases involving monetary

awards from the decision of the LA. The lawmakers clearly intended to make the bond a mandatory

requisite for the perfection of an appeal by the employer as inferred from the provision that an

appeal by the employer may be perfected “only upon the posting of a cash or surety bond.” The word

“only” makes it clear that the posting of a cash or surety bond by the employer is the essential and

exclusive means by which an employer’s appeal may be perfected. On the other hand, the word “may”

refers to the perfection of an appeal as optional on the part of the defeated party, but not to the

compulsory posting of an appeal bond, if he desires to appeal. Moreover, the filing of the bond is not

only mandatory but a jurisdictional requirement as well, that must be complied with in order to

confer jurisdiction upon the NLRC. Non-compliance therewith renders the decision of the LA final

and executory. This requirement is intended to assure the workers that if they prevail in the case,

they will receive the money judgment in their favor upon the dismissal of the employer’s appeal. It is

intended to discourage employers from using an appeal to delay or evade their obligation to satisfy

their employees’ just and lawful claims.

ISSUE 2:W/N the failure of EGI to comply with the requirement of posting a bond equivalent in amount to the

monetary award is fatal to their appeal.

YES. EGI, for filing its motion only on the final day within which to perfect an appeal, it cannot be allowed to

seek refuge in a liberal application of the rules. Under such circumstance, there is neither way for the NLRC to

exercise its discretion to grant or deny the motion, nor for the respondents to post the full amount of the

bond, without risk of summary dismissal for non-perfection of the appeal.

While the SC, in certain instances, allows a relaxation in the application of the rules, it never intends to forge a

weapon for erring litigants to violate the rules with impunity. The liberal interpretation and application of the

rules apply only in proper cases of demonstrable merit and other justifiable causes and circumstances, but

none obtains in this case. The NLRC had, therefore, the full discretion to grant or deny their motion to reduce

the amount of the appeal bond. The finding of the labor tribunal that EGI did not present sufficient

justification for the reduction thereof cannot be said to have been done with grave abuse of discretion. The

records show that after the motion to reduce appeal bond was denied, the NLRC still allowed EGI a new

period of 10 days from receipt of the order of denial within which to post the additional bond. Nevertheless,

EGI failed to post the additional bond and instead moved for reconsideration. On this score alone, their appeal

should have been dismissed outright for not having been perfected on time. The NLRC even bent over

backwards by entertaining the motion for reconsideration and even granted EGI another 10 days within

which to post the appeal bond. However, EGI did not take advantage of this liberality when it persistently

failed and refused to post the additional bond despite the extensions given it.

Petition granted. CA decision granting motion to reduce appeal bond and ordering the NLRC to give due

course to EGI’s appeal reversed and set aside. NLRC decision dismissing EGI’s appeal for failure to perfect an

appeal reinstated and affirmed.

4|S. Macapagal. BSU LAW 2012

The right to appeal is not a constitutional right, but a mere statutory privilege. Hence, parties who

seek to avail themselves of it must comply with the statutes or rules allowing it. To reiterate,

perfection of an appeal in the manner and within the period permitted by law is mandatory and

jurisdictional. The requirements for perfecting an appeal must, as a rule, strictly be followed. Such

requirements are considered indispensable interdictions against needless delays and are necessary

for the orderly discharge of the judicial business. Failure to perfect the appeal renders the judgment

of the court final and executory. Just as a losing party has the privilege to file an appeal within the

prescribed period, so does the winner also have the correlative right to enjoy the finality of the

decision.

5|S. Macapagal. BSU LAW 2012

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- OA6 - Ronin ChallengeДокумент134 страницыOA6 - Ronin ChallengeEd Bell100% (3)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Alec Baldwin Probable Cause StatementДокумент10 страницAlec Baldwin Probable Cause StatementLaw of Self Defense100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 4Документ12 страницConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 4Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Labor Standards Digests 3Документ5 страницLabor Standards Digests 3Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Human Rights Midterms Reviewer Under Atty. PrincipeДокумент39 страницHuman Rights Midterms Reviewer Under Atty. PrincipeStef Macapagal100% (34)

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 2Документ8 страницConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 2Stef Macapagal100% (1)

- Province of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesДокумент3 страницыProvince of North Cotabato V Government of The Republic of The PhilippinesStef Macapagal91% (11)

- BANAT V COMELECДокумент3 страницыBANAT V COMELECStef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 1Документ8 страницConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 1Stef Macapagal100% (2)

- Landmark GSIS Housing CaseДокумент12 страницLandmark GSIS Housing CaseStef Macapagal0% (1)

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 6Документ6 страницConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 6Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- 11 WUP V MaglayaДокумент2 страницы11 WUP V MaglayaAthena VenencianoОценок пока нет

- Tulfo V PeopleДокумент2 страницыTulfo V PeopleStef Macapagal100% (5)

- Labor Relations - JurisdictionДокумент7 страницLabor Relations - JurisdictionStef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Election Law Case Digest Matrix 1Документ5 страницElection Law Case Digest Matrix 1Stef Macapagal100% (1)

- Agrarian Law Case Digest Matrix Set 1Документ26 страницAgrarian Law Case Digest Matrix Set 1Stef Macapagal100% (7)

- Sample EngagementДокумент3 страницыSample Engagementkcsb researchОценок пока нет

- Republic of The Philippines) City of Pasig) S.S. AffidavitДокумент1 страницаRepublic of The Philippines) City of Pasig) S.S. AffidavitMikes Ekims100% (1)

- Copy Right and Neighboring RightsДокумент48 страницCopy Right and Neighboring RightsSiddarth Sunkari100% (2)

- 2017 Petitionn For Renewal NotarialДокумент3 страницы2017 Petitionn For Renewal NotarialMario Rizon Jr.Оценок пока нет

- HUMAN RIGHTS Digests Chapter 4, Under Atty. Pete PrincipeДокумент53 страницыHUMAN RIGHTS Digests Chapter 4, Under Atty. Pete PrincipeStef Macapagal100% (4)

- 2011 NLRC Rules of Procedure Notes and CasesДокумент62 страницы2011 NLRC Rules of Procedure Notes and CasesStef Macapagal100% (3)

- Israel G. Peralta vs. Court of AppealsДокумент2 страницыIsrael G. Peralta vs. Court of AppealsArianne AstilleroОценок пока нет

- FULL Download Ebook PDF Jones Sufrins Eu Competition Law Text Cases and Materials 7th Edition PDF EbookДокумент41 страницаFULL Download Ebook PDF Jones Sufrins Eu Competition Law Text Cases and Materials 7th Edition PDF Ebookcandace.binegar878100% (33)

- Alliance for Family Foundation vs Garin: Court denies motion, affirms due process required for FDA certificationДокумент2 страницыAlliance for Family Foundation vs Garin: Court denies motion, affirms due process required for FDA certificationAli Namla100% (1)

- Labor Law Review 2011 Digests 1Документ33 страницыLabor Law Review 2011 Digests 1Stef Macapagal100% (3)

- Labor Relations - Certificate of Non-Forum ShoppingДокумент2 страницыLabor Relations - Certificate of Non-Forum ShoppingStef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Lina v. PanoДокумент2 страницыLina v. PanoStef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Labor Relations - PrescriptionДокумент5 страницLabor Relations - PrescriptionStef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- R T - R D R, J - (237 SCRA 324) : Taxation Law Digests For Cases Suggested by ExcellentДокумент9 страницR T - R D R, J - (237 SCRA 324) : Taxation Law Digests For Cases Suggested by ExcellentStef Macapagal100% (1)

- Election Law Case Digest Matrix 2Документ6 страницElection Law Case Digest Matrix 2Stef Macapagal100% (1)

- Labor Standards Digests 4Документ3 страницыLabor Standards Digests 4Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Labor Standards Digests 1Документ9 страницLabor Standards Digests 1Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Labor Standards Digests 2Документ4 страницыLabor Standards Digests 2Stef MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 3Документ11 страницConstitutional Law Case Digest Matrix Set 3Stef Macapagal100% (1)

- Plastic Waste Management Rules 2016 PDFДокумент6 страницPlastic Waste Management Rules 2016 PDFPratul ChoudhuryОценок пока нет

- Meg Whitman Pledge Donation FormДокумент1 страницаMeg Whitman Pledge Donation FormNicholasQ2Оценок пока нет

- Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) of Name & Gender Update Request Under Exception Handling ProcessДокумент6 страницStandard Operation Procedure (SOP) of Name & Gender Update Request Under Exception Handling ProcessMaulik PatelОценок пока нет

- Leonel Hernandez OpinionДокумент38 страницLeonel Hernandez OpinionErika EsquivelОценок пока нет

- Chapter 5 - Introduction To Differential Analysis of Fluid MotionДокумент4 страницыChapter 5 - Introduction To Differential Analysis of Fluid MotionBin RenОценок пока нет

- Jon Hamm Penis Picture FilingДокумент21 страницаJon Hamm Penis Picture FilingLaw&CrimeОценок пока нет

- Republic Act No. 9829 An Act Establishing The Pre-Need Code of The PhillpplnesДокумент19 страницRepublic Act No. 9829 An Act Establishing The Pre-Need Code of The PhillpplnesKhalee SiОценок пока нет

- PNB Records Inspection Rights of Minority ShareholderДокумент9 страницPNB Records Inspection Rights of Minority ShareholderJM GuevarraОценок пока нет

- Pro Reo Principle: Gatchalian, G.R. No. L-12011-14 (1958) ) in Dubio Pro ReoДокумент4 страницыPro Reo Principle: Gatchalian, G.R. No. L-12011-14 (1958) ) in Dubio Pro ReoMikaela DeguitoОценок пока нет

- A Reaction Paper About Issues and Problems in Public Governance Related To Ethics and AccountabilityДокумент11 страницA Reaction Paper About Issues and Problems in Public Governance Related To Ethics and AccountabilityjosephcruzОценок пока нет

- Ebook PDF Successful Contract Administration PDFДокумент41 страницаEbook PDF Successful Contract Administration PDFtheodore.brooke313100% (31)

- TCONT600AF11MA/TCONT602AF22MA Programmable Comfort Control: Owner'S GuideДокумент28 страницTCONT600AF11MA/TCONT602AF22MA Programmable Comfort Control: Owner'S GuideJesus DavalosОценок пока нет

- Philippine Politics GuideДокумент2 страницыPhilippine Politics GuidePaul Martin EscalaОценок пока нет

- Sandisk Storage Malaysia Sdn. BHDДокумент1 страницаSandisk Storage Malaysia Sdn. BHDJtech Connection EnterpriseОценок пока нет

- Unit 4Документ8 страницUnit 4SYLVINN SIMJO 1950536Оценок пока нет

- CombinedДокумент18 страницCombinedDeepak BishnoiОценок пока нет

- North Tampa Bass Club Bylaws 2024Документ8 страницNorth Tampa Bass Club Bylaws 2024api-90663565Оценок пока нет

- Gashem Shookat Baksh vs. CA, 219 SCRA 115Документ5 страницGashem Shookat Baksh vs. CA, 219 SCRA 115Ariza ValenciaОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 144214 - Villareal v. RamirezДокумент5 страницG.R. No. 144214 - Villareal v. RamirezKimmy May Codilla-AmadОценок пока нет

- Ethics Assignment 15 NovДокумент5 страницEthics Assignment 15 NovRounak VirmaniОценок пока нет