Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Micah T. Lewin - Guidelines For Philosophical Writing (Sept 2017)

Загружено:

KARLO MARKO VALLADORESОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Micah T. Lewin - Guidelines For Philosophical Writing (Sept 2017)

Загружено:

KARLO MARKO VALLADORESАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Guidelines for Philosophical Writing Professor Micah T.

Lewin

Writing a philosophy paper will be quite a bit different than writing you may have done for other courses or in other

parts of your life. Standards for philosophical writing are particularly demanding and exacting. Philosophical

writing requires clarity, precision, consistency, detailed analysis of issues, charitable reconstruction/consideration of

other authors’ positions, rigorous argument for your own position (using well-reasoned justifications and examples),

anticipation of potential objections, and consideration of plausible alternatives to one’s own views all within a

tightly-organized, well-structured, and easy-to-follow essay. This will take some time and effort to master. But

happily, all of these skills can be put to use outside of philosophy class: the rigorous demands of crafting

philosophical essays can shape you into a better, more persuasive writer.

For further guidance, please have a look at the helpful resources on of my undergraduate teachers, Professor Jim Pryor of NYU,

kindly provides on his website: http://www.jimpryor.net/teaching/guidelines/writing.html

On Reading Philosophy: http://www.jimpryor.net/teaching/guidelines/reading.html

On Terms/Methods for Philosophical Arguments: http://www.jimpryor.net/teaching/vocab/

Guidelines for Philosophical Writing

(A) Good Philosophical Writing begins with Good Philosophical Reading.

a. Go back and re-read: closely re-examine the relevant readings and class materials with an eye to the essay

prompt you will be addressing.

b. Take notes: these should help you in charitably reconstructing other authors’ view in providing the relevant

exposition for your own paper.

(B) Compose a Detailed Outline or Plan for your Paper.

a. Outlines help you see if there are any gaps in your reasoning or argument.

b. An outline also helps you improve the structure and flow of your paper: you have a bird’s-eye-view of the way

the pieces of the essay fit together (or don’t yet fit together, so you can fix it).

c. Break your argument down into intelligible pieces/sections and make sure you are following the expectations

of the “Structuring Your Paper” section below (F).

(C) Write Several Drafts of Your Paper: Write, Revise, Rework, & Rewrite, and then again…

a. Your first draft will unlikely be fully satisfactory.

b. Give yourself some time away from your just-completed draft of the paper; then come back and look at it

critically with fresh eyes.

c. Imagine your target audience for the paper are the most highly critical, uninterested, unknowledgeable readers

you can think of.

i. In the writing/revising process, I find it is most helpful to imagine that your essay will be read by the

most highly critical, uninterested, unknowledgeable reader you can think of.

ii. (For me, I think of waking up my unforgiving, grumpy father late at night to look over my paper.)

iii. Your paper should be sufficiently clear, comprehensible, plausible, and convincing to appease even

that kind of harsh, uncharitable reader. If that “nightmare reader” would be able to understand your

essay, follow its line of thought, and find it plausible and strongly-enough argued, then you have

probably done your job well.

iv. So, when you re-read/revise your paper, imagine reading it from the perspective the most harsh,

uninterested, unknowledgeable critic out there.

v. Expecting your audience to be such “nightmare readers” is an exercise in preparing for the worst.

Preparing for the worst possible audience will make your writing much easier to follow and your

arguments much stronger even for more typical readers.

d. Revising, reworking, and rewriting a couple of times will vastly improve the clarity, precision, strength, and

quality of your final draft. Use this guide and the Philosophy Paper Grading Rubric during the revision/rewrite

process.

Rev. 09/2017 Guidelines for Philosophical Writing, p. 1 of 4

Guidelines for Philosophical Writing Professor Micah T. Lewin

(D) Originality/Creativity

a. Your paper should show originality and creativity—in particular, in either the position/thesis you defend

and/or the arguments you provide to support your thesis (or both). Your essays are a forum to demonstrate

independent, novel, and insightful thinking, and this can come through especially in your thesis and the

arguments you present for your thesis.

b. You may also demonstrate creativity/originality in the insightful, novel way you analyze, explain, or reconstruct

background information or other philosophers’ positions/arguments.

c. You will not always or even often be able to come up with your own new philosophical position or thesis on an

issue whole-cloth.

i. Philosophy is full of timeworn debates where a huge range of potential positions on issues has long

been articulated & discussed. There isn’t a lot of completely untraveled ground.

ii. Given this, it will be difficult to come-up with a wholly novel, viable thesis for a short essay

assignment. It is difficult enough for professional Philosophers to do so!

d. Rather, what is expected is that you show independent, creative thought in how you present your thesis, the

arguments your present for it, and/or the way you and explain/analyze the subject matter/philosophical

background and others’ positions on the issue.

i. You might seek to present an existing thesis in a novel or illuminating way.

ii. You should seek to come up with original arguments, novel justifications, and new examples in

support of your thesis (even if the thesis is not wholly original).

iii. Your explanation of relevant ideas/concepts and reconstruction of others’ views about the issues in

contention can demonstrate originality.

iv. This might take the form of combining ideas from different sources in a creative or novel way.

e. Showing some independent thought and philosophical insight is a major goal of the exercise. You are

not to merely copy, parrot, quote, and/or paraphrase somebody else’s paper on the same topic. You are

expected to show some original ideas & thought. Even if you cite this author (which you should!), if you

simply (or largely) present a wholesale copy of another author’s work this is, in effect, presenting someone

else’s work as your own and as such is academically dishonest and grounds not only for a failing grade, but

also potentially for disciplinary action.

(E) Synthesis/Integrative Understanding

a. Your paper should present an integrative understanding of the subject matter, the issue in contention, other

authors positions, and your own thesis into a coherent, overarching whole (insofar as you can do so

illuminatingly and accurately).

i. Your essay should provide the reader with at least some integrative, overarching framework or

picture of the issue at hand that illuminatingly captures the subject matter as a whole.

ii. In reading your paper, the reader should not only garner an understanding of your thesis/position on

a topic. They should also get some idea of where your thesis fits in within the “philosophical

landscape” about that issue/subject matter.

1. Your paper should present itself as not only a reliable guide to what you, the author,

happens to think about an issue.

2. It should present itself as a reliable guide-map for the relevant philosophical terrain. Your

paper should educate the reader about the issue as a whole: the background

matters/concepts/ideas, alternative/opposing positions, your own position, and etc. should

all be illuminatingly mapped out.

b. It will not be easy to reliably capture such a synthetic, integrative, holistic picture of the subject matter within

your first draft. Rather, this overarching framework or guide of the philosophical terrain is more likely to

emerge over the course of outlining, drafting, revising, and re-writing your paper.

i. Such a synthesis may only emerge and become well-articulated in later drafts of your paper.

ii. Revising and re-writing your paper with fresh eyes should help you improve this integrative aspect of

your philosophical writing. It will give you a better, bird’s-eye perspective on what you’ve written and

Rev. 09/2017 Guidelines for Philosophical Writing, p. 2 of 4

Guidelines for Philosophical Writing Professor Micah T. Lewin

how well it presents an overview or map for the philosophical terrain and the place of your thesis

(versus alternative positions) therein.

(F) Structuring Your Paper

a. Your Introduction

i. Your Introduction should:

1. concisely introduce the topic of the paper.

2. contain a clear statement of your thesis (what you’ll be arguing for/your conclusion).

3. contain a clear statement of how you’ll argue for it (your argumentative plan for the paper).

ii. Your introduction should not contain excess fluff, filler, or frill: it should be to the point (topic, thesis,

plan) and as concise as possible.

b. Body of the Paper

i. Provide an explanation and analysis of the topic/issue and an exposition of the relevant background

literature.

1. Paraphrasing, or putting matters in your own words, is preferable to direct quote.

2. Explain the topic/issue being addressed and the ideas/concepts involved therein as clearly

and precisely as you can. Analyze/break down the matter into their constituent parts and

their relations.

3. Provide a clear & charitable interpretation of the relevant sections of other authors’ work,

including those you are arguing against. Do not present others’ views as straw men (a

fallacy we discussed). Your own argument is improved and strengthened to the extent that

you are able to argue against opposing views cached in their strongest possible terms.

ii. Present your own argument in a clear, precise, consistent way, avoiding argumentative fallacies.

1. Pitch your claims at an appropriate level of strength, avoiding overstatements—

appropriately qualify or temper your premises and conclusions.

2. Make the considerations or reasons you present in favor of your thesis (premises), as clear,

precise, and concise as you possibly can.

3. Make it clear how your arguments lead to your thesis/conclusion. The

inferential/argumentative structure of your paper should not be a guessing game: it should

be obvious to the reader how the pieces fit together in support of your thesis/conclusion.

4. Be sure to think about how to make each example or each consideration as strong as it can

possibly be in support of your argument and thesis. Ask what each detail might do, and

whether changing, removing, or adding it strengthens your argumentative point.

iii. Conclusion: Tie up Loose Ends/Tidy-up Unfinished Business.

1. Again, no fluff: stay on point and be as concise as possible.

2. Your conclusion should at least anticipate, raise, and consider objections/alternatives to your

view.

a. What are two or three of the strongest objections, counter-arguments, or

alternative positions to your own position/argument that you can foresee?

b. Present a few of the best responses (if any) you can make to these objections or

alternatives and give a frank assessment of where this leaves your argument.

3. You might use the conclusion to also consider/be self-reflective about the actual strength of

your own argument and the degree of support you have given your thesis/conclusion.

4. You might use the conclusion to briefly consider some interesting, pertinent, or controversial

implications of your position, a full discussion of which would fall beyond the scope of the

paper/assignment.

(G) Readability

a. Make sure your writing is as easy to understand and comprehensible as it can be. Avoid overly-complex,

ornate, or overly-technical phrasing when doing so would stand in the way of comprehensibility.

b. Choose your words precisely.

Rev. 09/2017 Guidelines for Philosophical Writing, p. 3 of 4

Guidelines for Philosophical Writing Professor Micah T. Lewin

c. Be as clear as possible.

d. Make your writing as concise as possible without sacrificing clarity or important detail & nuance.

e. When you use technical vocabulary or concepts, make sure you define, explain, and employ them

appropriately/accurately.

f. Avoid overly complex sentences and phrases. Simplify and break these down into shorter pieces. Think about

what each word is doing for you, and edit out words/phrases that are unnecessary for your point to come

across.

(H) Organization

a. Your paper should have an argumentative roadmap in the introduction. Follow that roadmap in the paper.

i. It is no good to present an argumentative plan for the paper and then not follow it, or deviate from it

without explanation.

ii. Without a roadmap, your paper will be more difficult to follow and thus not as strong as it could be.

b. Your paper should employ a number of helpful transitional/organization-guiding phrases (i.e. guide/sign post

words like “first,” “next,” “last,” or etc.) throughout to let readers know they are in the argument plan.

c. As far as possible, clearly spell out the role of each paragraph and section of your paper, and simplify these as

best you can. If the point of one paragraph is too convoluted and/or multifarious your readers will likely have

difficulty following.

(I) Citing Sources

a. If you rely on materials from somewhere else, whether assigned readings or elsewhere, you must cite your

sources at the points in your paper where you use them. There is no shame in drawing upon someone else’s

ideas provided you give her or him proper credit. You must cite even when you paraphrase rather than directly

quote: if the idea, even if not the exact words, came from someone else, you must attribute that author.

b. I do not require a specific citation style or format, but the content of your citation should enable the reader to

easily find where you derived the material.

i. Citations should occur at the points in your paper where you are utilizing or drawing upon the

material you are citing. Regardless of whether you are directly quoting or paraphrasing, and

regardless of whether you are using footnotes, endnotes, or parenthetical citations, if you got the

idea from someone else, cite it where you use it. When in doubt, attribute.

ii. Merely having a Works Cited page at the end of your paper is not sufficient attribution for works your

quoted from or drew upon in your paper. It is not enough to put a works cited page at the end if you

did not note the places in your paper where you cited that material (whether parenthetically, with

footnotes, or endnotes). A Works Cited page is just a general list of references; it is not a replacement

for specific citations of works you draw upon at the points you use them in your essay.

iii. In papers for my students, I personally do not care how you do your citations, stylistically. It can be a

footnote, endnote, parenthetical citation, etc., and it does not have to follow any particular rulebook

of citation format (MLA, Chicago, etc.). Note: this lenience may not apply for other professors!

iv. As a matter of what substantively goes into your citation, your citations should provide enough detail

that your reader can readily find where you got the material you are referencing or drawing

upon. Again, I, personally, do not really care how you achieve this, though others may. For instance,

if you just list a last name and a page number in a footnote/endnote/parenthetical, and then have a

Works Cited at the end to spell out what these names refer to, that's fine. Or, e.g., if you have a

scheme where your first footnote lists the whole reference, and then subsequent citations of that

work use an abbreviation to reference back to that original citation, that's fine too. As long as your

citations make it easy enough for the reader to find where you got the material (down to the

relevant page in the work you are citing—though, not if a website), that should suffice.

c. The rule is, when in doubt, attribute: always cite your sources. It is better to err on the side of over-citing than

under-citing. If you do not cite your sources, then this constitutes plagiarism, which I am bound by College

and University policy to treat as a disciplinary matter not just a grading matter. Please do not try to get away

with academic dishonesty and plagiarism: it isn’t worth it. Your own work is always the better option.

Rev. 09/2017 Guidelines for Philosophical Writing, p. 4 of 4

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

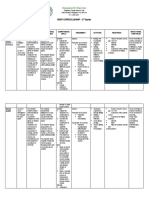

- DCM RELIGION Grade 8 2nd QuarterДокумент8 страницDCM RELIGION Grade 8 2nd QuarterKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- ENGLISH 10 ONLINE DCM-2nd QuarterДокумент5 страницENGLISH 10 ONLINE DCM-2nd QuarterKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- DCM RELIGION Grade 10 2nd QuarterДокумент6 страницDCM RELIGION Grade 10 2nd QuarterKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Seminario de San Jose: Diary Curriculum MapДокумент8 страницSeminario de San Jose: Diary Curriculum MapKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- CURRICULUM MAP Grade 7 2020-2021 2nd QuaterДокумент10 страницCURRICULUM MAP Grade 7 2020-2021 2nd QuaterKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- CURRICULUM MAP Grade 9-2ND QUARTERДокумент13 страницCURRICULUM MAP Grade 9-2ND QUARTERKARLO MARKO VALLADORES100% (2)

- A Brief Introduction To Plato's RepublicДокумент5 страницA Brief Introduction To Plato's RepublicKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Authorization: (This Form Must Be Notarized.)Документ1 страницаAuthorization: (This Form Must Be Notarized.)KARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Practical Research 2 Learning CompetenciДокумент2 страницыPractical Research 2 Learning CompetenciKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Understanding The Political Thought of Pura Villanueva KalawДокумент7 страницUnderstanding The Political Thought of Pura Villanueva KalawKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Tos1 Research and LogicДокумент5 страницTos1 Research and LogicKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Education Policies For Global Development: Project CoordinatorДокумент2 страницыEducation Policies For Global Development: Project CoordinatorKARLO MARKO VALLADORESОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- #Hyperion by John KeatsДокумент4 страницы#Hyperion by John KeatsNoor UlainОценок пока нет

- 30 Beautiful DuaДокумент7 страниц30 Beautiful DuaHassan NawazОценок пока нет

- A2 - Bizuayehu Tadesse - 510AДокумент13 страницA2 - Bizuayehu Tadesse - 510ABizuayehu TadesseОценок пока нет

- Lesson 2: Academic Texts Across The DisciplinesДокумент21 страницаLesson 2: Academic Texts Across The DisciplinesHanna MendozaОценок пока нет

- Behaviorism: by Mahnoor Shakeel Roll No:12Документ84 страницыBehaviorism: by Mahnoor Shakeel Roll No:12Mahnoor ShakeelОценок пока нет

- Life and Works of Rizal Module For Finals SY 2020-2021: Lesson 1 Self Discipline: A Call For Our LivesДокумент4 страницыLife and Works of Rizal Module For Finals SY 2020-2021: Lesson 1 Self Discipline: A Call For Our LivesJim Michael Arce CasauranОценок пока нет

- Gency, ST Cture: Theories of Action Versus Institutional TheoriesДокумент2 страницыGency, ST Cture: Theories of Action Versus Institutional TheoriesPesquisadora OlpefОценок пока нет

- Laungani (2002)Документ9 страницLaungani (2002)SITI ZURAIDAH BINTI MOHAMEDОценок пока нет

- Matt Stuart: Alles, Was Das Leben Bieten KannДокумент2 страницыMatt Stuart: Alles, Was Das Leben Bieten KannCilouОценок пока нет

- Shaista Younas 3088 Prose 2Документ14 страницShaista Younas 3088 Prose 2Zeeshan ch 'Hadi'Оценок пока нет

- THE Mcdonaldization of The Contemporary Society: by George RitzerДокумент15 страницTHE Mcdonaldization of The Contemporary Society: by George RitzerKen HendricОценок пока нет

- Colonialism, Modernity, and The Creation of Global InequalityДокумент2 страницыColonialism, Modernity, and The Creation of Global InequalityTanunoy CabusasОценок пока нет

- Engineering Data and Analysis - Notes 6Документ4 страницыEngineering Data and Analysis - Notes 6Chou Xi MinОценок пока нет

- Handouts in EAPP - Lesson 1 and 2 - Q2Документ2 страницыHandouts in EAPP - Lesson 1 and 2 - Q2Oci Rosalie MarasiganОценок пока нет

- Refugee Performance: Aesthetic Representation and Accountability in Playback TheatreДокумент6 страницRefugee Performance: Aesthetic Representation and Accountability in Playback TheatreCarina CoráОценок пока нет

- Contextual Action Theory in Career CounsДокумент16 страницContextual Action Theory in Career CounsIsrael Gil Aguilar LacayОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент68 страницPDFsagggasgfaОценок пока нет

- MMW MIDTERMS and FINALS REVIEWER by ChaiДокумент11 страницMMW MIDTERMS and FINALS REVIEWER by ChaiGlaiza D VillenaОценок пока нет

- Making Connections: Learner's Module For English 9 Quarter 2 Module 3Документ3 страницыMaking Connections: Learner's Module For English 9 Quarter 2 Module 3joy sumerbangОценок пока нет

- Indian Aesthetics CIAДокумент6 страницIndian Aesthetics CIAArjun Anil BhaskarОценок пока нет

- Tertullian Apology. de Spectaculis Minucius Felix (Loeb Classical Library)Документ492 страницыTertullian Apology. de Spectaculis Minucius Felix (Loeb Classical Library)ahilepeleianulОценок пока нет

- PSY10008 Learning Lesson Outline 2022Документ2 страницыPSY10008 Learning Lesson Outline 2022saraОценок пока нет

- Calvin and Hobbes #5 - Revenge of The Baby-Sat 1988-1989Документ295 страницCalvin and Hobbes #5 - Revenge of The Baby-Sat 1988-1989Balwant Rai89% (18)

- The Analogies in GitaДокумент6 страницThe Analogies in GitaSivasonОценок пока нет

- 8 Sacred Secrets - Keys To Unlock Your Womb PDFДокумент6 страниц8 Sacred Secrets - Keys To Unlock Your Womb PDFDaniela IlieОценок пока нет

- Andrew KlimanДокумент11 страницAndrew KlimanLiam MurciaОценок пока нет

- TO LAW Comprehensive Reviewer SY 2012 - 2013Документ44 страницыTO LAW Comprehensive Reviewer SY 2012 - 2013bobbyrickyОценок пока нет

- A Comparative Analysis of Existing Ancient Indian Gurukul Models For Building A Futuristic Educational PerspectiveДокумент17 страницA Comparative Analysis of Existing Ancient Indian Gurukul Models For Building A Futuristic Educational PerspectiveAnonymous CwJeBCAXpОценок пока нет

- Ecology and UtopiaДокумент19 страницEcology and UtopiaTeodora FlrОценок пока нет

- GoldenBlade 1980Документ91 страницаGoldenBlade 1980David BurrisОценок пока нет