Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Thomas Merton's Preface To

Загружено:

Micha Jazz0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров3 страницыThomas Merton's Preface to the Wisdom of the desert is a useful introduction to eremitism. The hermits believed there was no such thing as a "christian state" the desert hermits were not pragmatic or negative individualists, not even rebels against society. They simply believed that their values were sufficient for ruling themselves, and for fellowship.

Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Thomas Merton's preface to

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThomas Merton's Preface to the Wisdom of the desert is a useful introduction to eremitism. The hermits believed there was no such thing as a "christian state" the desert hermits were not pragmatic or negative individualists, not even rebels against society. They simply believed that their values were sufficient for ruling themselves, and for fellowship.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров3 страницыThomas Merton's Preface To

Загружено:

Micha JazzThomas Merton's Preface to the Wisdom of the desert is a useful introduction to eremitism. The hermits believed there was no such thing as a "christian state" the desert hermits were not pragmatic or negative individualists, not even rebels against society. They simply believed that their values were sufficient for ruling themselves, and for fellowship.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

HOME | Articles | Reviews | Features

ARTICLES ! Hermits in History: West

Thomas Merton's Preface to The Wisdom of the Desert

Thomas Merton published The Wisdom of the Desert in 1960, his

contribution to short works collecting favorite sayings of the

Christian desert hermits, or Desert Fathers. While the selecting was

doubtless an enjoyable task, the Preface to the little ensemble

surprisingly emerges as a clear, precise and useful introduction to

eremitism as a whole.

Merton begins his introduction by asking what the hermits sought

in going to the desert, in abandoning the cities for solitude. In a

word, "salvation," he says. But Merton carefully notes that

abandoning the cities was not only abandoning the pagan character of urban life

but also abandoning their presumeably increasing Christian presence, "when the

'world' became unofficially Christian." Merton notes that

these men seem to have thought ... that there is really no such thing as a

"Christian state." They seem to have doubted that Christianity and politics

could ever be mixed to such an extent as to produce a fully Christian society

... for ... the only Christian society was spiritual and extramundane.

Merton argues that these hermits were ahead of their time, not behind it, that they

understood what was necessary -- and unnecessary -- for establishing a new society.

The line of Merton's thought may show its age in Merton's vocabulary,

describing the hermits as the new "axial" men, as "personalists" -- but the point is

important. The hermits were not pragmatic or negative individualists, not even

rebels against society. They might be seen as "anarchists," -- and "it will do no

harm to think of them in that light." They simply believed that their values were

sufficient for ruling themselves, and for providing for humane fellowship. While

acknowledging the titular authority of bishops, these were "far away" and had little

to say about the desert for at least a century.

The hermits sought their own self, rejecting the false self "fabricated under social

compulsion in 'the world.'" They accepted dogmatic formulas of the Christian faith,

but without controversy, in their simplest and most elemental forms. But while the

monks or cenobites living in nearby monasteries also conceived of formulas as

necessary scaffolding to their spiritual growth, the hermits were entirely free to

conform only to the "secret, hidden, inscrutable will of God which might differ very

notably from one cell to another!" Merton quotes an early saying of St. Anthony:

"Whatever you see your soul to desire according to God, do that thing, and you

shall keep your heart safe."

But the quote refers specifically to the perogative of the hermit, to one

who was very alert and very sensitive to the landmarks of a trackless

wilderness. The hermit had to be a man mature in faith, humble and

detached from himself to a degree that is altogether terrible.

None other than the hermit could abide within these apparent extremes. Hence the

prescribed maturity.

He could not afford to be an illuminist. He could not dare risk attachment to

his own ego, or the dangerous ecstacy of self-will. He could not retain the

slightest identification with his superficial, transient, self-constructed self.

The hermit, above any other person, had to lose himself to a transcendent and

mysterious yet inner reality. To Merton this reality was Christ. Clearly, this Christ

was not the popularized image of icons and evocations but a transcendent being

dissolved from society and convention. How, then, could the hermit not lead a life of

simplicity, compunction, solitude, labor, poverty, charity, purity of heart? The fruit

of this self-discipline was quies, "rest." This "rest" the world -- meaning society --

could not offer.

Merton notes that the desert hermits never spoke of this quies, never distinguished

it from their way of life. They did not theorize, philosophize, or theologize. "In many

respects, therefore," declares Merton rightly, "these Desert Fathers had much in

common with Indian Yogis and with Zen Buddhist monks of China and Japan."

As is well known to those familiar with his biogrphy, Merton always chafed with his

own monasteric life -- cenobitism -- while fulfilling a grand service to his readers by

writing, a privilege that monastic life afforded him, or rather was afforded to him by

his abbots. But he never shrunk from criticizing his contemporaries. Thus Merton

states that men like the desert hermits don't exist in monasteries. Though monks

leave the society of "the world," they conform to the society into which they enter,

with its own norms and conventions, rules and penalties. While many desert

hermits were once monks, they left monastic society and established a new path of

"fabulous originality," to which nothing contemporary in Christianity can compare.

The desert hermits

neither courted the approval of their contemporaries nor sought to provoke

their disapproval, because the opinions of others had ceased, for them, to be

matters of importance. They had no set doctrine about freedom, but they had

in fact become free by paying the price of freedom.

This price was the experience of solitude and simplicity. The words and sayings of

the desert fathers are a prompt to reflection, but it was the lived experience of

solitude that truly counted for them. Hence their sayings are plain, pithy, and

trenchant, born of the experience of solitude and wrestling with the ego. Merton

affirms their "existential quality." The hermits were humble and silent, with not

much to say, which makes reading them refreshing. The secrets to their lives are

thus revealed directly in their manner of living, expressed in it, and therefore

deducible indirectly from their sayings.

Today (as much as in the past), the desert hermits are too often portrayed as

ascetic fanatics. This is entirely the conclusion of one who has not read their sayings

and tried to penetrate their values. In fact, the hermits strike the careful reader as

"humble, quiet, sensible people, with a deep knowledge of human nature." Their

world seethed in controversy but they "kept their mouths shut" -- not because they

were ignorant or opinionless but because they became like the desert, offering

nothing to the worldly but "discreet and detached silence."

Merton notes that the desert hermits were mostly "on their way" and not boasters

of arrival. They were not passionless, bloodless, or "beyond all temptation." This is

what makes their sayings and their way of life so compelling. The were laborers,

and showed genuine concern for the welfare of their fellows in charity, exhibiting

the ideal virtue of Christianity.

Isolation in the self, inability to go out of oneself to others, would mean

incapacity for any form of self-transcedence. To be thus the prisoner of one's

own selfhood is, in fact, to be in hell: a truth that Sartre, though professing

himself an atheist, has expressed in the most arresting fashin in his play No

Exit (Huis Clos).

Ultimately, charity is love, and holds the primacy over everything else in the

spiritual life. Love in fact is the spiritual life, avers Merton, meaning not sentiment,

nor mere almsgiving, nor mere identification with one's brothers and sisters

because they are like oneself. Love here presents itself in all humility and with

reverence toward the other and the other's integrity, identifying with that which is

transcendent in both oneself and another. Love presumes a death of ego in order to

accommodate the needs of charity and of others. The work of the hermits, which is

the spiritual life, can accommodate the needs of others in this way, looking to the

shortcomings of self always, and taking up the proscription of Jesus to judge no

one. In this one is free, free to pursue one's own path without obligation.

By the end of the 5th century, the monasteries of Scete and Nitria, so close to the

desert, had become "the world." Merton notes how they had virtually become cities,

with laws and penalties. "Three whips hung from a palm tree outside the church of

Scete: one to punish delinquent monks, one to punish thieves, and one for

vagrants." To this the desert hermits would profoundly demur. Thehermits

represented the "primitive anarchic desert ideal." And in the desert, in solitude, all

transgressions eventually serve to enlighten the wayward soul.

Merton completes his preface with a sketch of some important names now familiar

to the reader of the sayings: Arsenius, Moses, Anthony, Paphnutius, Pastor, John

the Dwarf. Merton's book is brief but invaluable as a start, and worth revisiting for

the familiar.

Merton concludes with a telling paragraph that is every bit as relevant today as

when he wrote it in 1960:

It would perhaps be too much to say that the world needs another movement

such as that which drew these men into the deserts of Egypt and Palestine.

Ours is certainly a time for solitaries and for hermits. But merely to reproduce

the simplicity, austerity and prayer of these primitive souls is not a complete

or satisfactory answer. We must transcend them, and transcend all those who,

since their time, have gone beyond the limits which they set. We must

liberate ourselves, in our own way, from involvement in a world that is

plunging to disaster. But our world is different from theirs. Our involvement

in it is more complete. Our danger is far more desperate. Our time, perhaps,

is shorter than we think.

¶

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Thomas Merton's The Wisdom of the Desert is published by New Directions (New

York, 1960), Sheldon (London, 1974), and Shambhala (Boston, 1994 and

reprinted 2004).

URL of this page: http://www.hermitary.com/solitude/merton_wisdom.html

© 2011, the hermitary and Meng-hu

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Wps Gtaw Monel b127 b164Документ2 страницыWps Gtaw Monel b127 b164Srinivasan Muruganantham67% (3)

- Squares and Square Roots Chapter Class ViiiДокумент24 страницыSquares and Square Roots Chapter Class ViiiManas Hooda100% (1)

- Ilmu KhotifДокумент28 страницIlmu KhotifAndré Martins78% (27)

- 5 Kingdoms of OrganismsДокумент13 страниц5 Kingdoms of OrganismsChoirul Anam100% (2)

- Method Statement For Painting WorksДокумент2 страницыMethod Statement For Painting Worksmustafa100% (3)

- Shadow UAV HandbookДокумент57 страницShadow UAV HandbookGasMaskBob100% (2)

- Ruger MKIIДокумент1 страницаRuger MKIIMike Pape100% (1)

- Macedonian KavalДокумент1 страницаMacedonian Kavalmikiszekely1362Оценок пока нет

- EV Connect What Is EVSE White PaperДокумент13 страницEV Connect What Is EVSE White PaperEV ConnectОценок пока нет

- Portable Manual - DIG-360Документ44 страницыPortable Manual - DIG-360waelmansour25Оценок пока нет

- Notes Ch. 4 - Folk and Popular CultureДокумент7 страницNotes Ch. 4 - Folk and Popular CultureVienna WangОценок пока нет

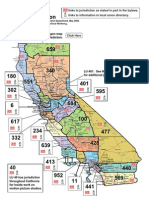

- CA InsideДокумент1 страницаCA InsideariasnomercyОценок пока нет

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science IiiДокумент3 страницыDetailed Lesson Plan in Science Iiicharito riveraОценок пока нет

- 18-039 Eia 07Документ34 страницы18-039 Eia 07sathishОценок пока нет

- Danh M C AHTN 2017 - HS Code 2017 PDFДокумент564 страницыDanh M C AHTN 2017 - HS Code 2017 PDFBao Ngoc Nguyen100% (1)

- EE 411-Digital Signal Processing-Muhammad TahirДокумент3 страницыEE 411-Digital Signal Processing-Muhammad TahirQasim FarooqОценок пока нет

- Project Report of Dhanashree Goat FarmДокумент56 страницProject Report of Dhanashree Goat FarmNandan GowdaОценок пока нет

- Block-1 BLIS-03 Unit-2 PDFДокумент15 страницBlock-1 BLIS-03 Unit-2 PDFravinderreddynОценок пока нет

- Pastor O. I. Kirk, SR D.D LIFE Celebration BookДокумент63 страницыPastor O. I. Kirk, SR D.D LIFE Celebration Booklindakirk1100% (1)

- Yamaha rx-v395 v395rds htr-5130 5130rdsДокумент55 страницYamaha rx-v395 v395rds htr-5130 5130rdsdomino632776Оценок пока нет

- 020 Basketball CourtДокумент4 страницы020 Basketball CourtMohamad TaufiqОценок пока нет

- 2014 Catbalogan Landslide: September, 17, 2014Документ6 страниц2014 Catbalogan Landslide: September, 17, 2014Jennifer Gapuz GalletaОценок пока нет

- MC 1Документ109 страницMC 1ricogamingОценок пока нет

- Quarter 4 - Week 1Документ44 страницыQuarter 4 - Week 1Sol Taha MinoОценок пока нет

- An Infallible JusticeДокумент7 страницAn Infallible JusticeMani Gopal DasОценок пока нет

- Idlers: TRF Limited TRF LimitedДокумент10 страницIdlers: TRF Limited TRF LimitedAjit SarukОценок пока нет

- 9 Quw 9 CjuДокумент188 страниц9 Quw 9 CjuJavier MorenoОценок пока нет

- Anatomia Dezvoltarii PancreasuluiДокумент49 страницAnatomia Dezvoltarii Pancreasuluitarra abuОценок пока нет

- Tools, Equipment, and ParaphernaliaДокумент35 страницTools, Equipment, and Paraphernaliajahnis lopez100% (1)

- Procrustes AlgorithmДокумент11 страницProcrustes AlgorithmShoukkathAliОценок пока нет