Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

KLD From Gin Girls To Scavengers

Загружено:

ShipShapeОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

KLD From Gin Girls To Scavengers

Загружено:

ShipShapeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

From Gin Girls to Scavengers

Women in Raniganj Collieries

In the beginning, the coal mining industry employed women from the adivasi and lower caste

communities in various stages of production. Their role continued to be significant as long as

technology remained labour-intensive and collieries were small and surface-bound. The

expansion of the industry and increasing mechanisation saw a decline in women’s

participation. This paper based on research in the Raniganj coalbelt in eastern India describes

how the work of resource extraction becomes gendered, the growing marginalisation of

women, and their increasing alienation from access to environmental resources and their

transformation into illegitimate and invisible beings.

KUNTALA LAHIRI-DUTT

I were surface-bound. The participation of as the adivasis and low ranking castes,

Introduction women in mines has declined remarkably and women have remained largely ex-

in last three decades of the industry’s cluded in spite of a multitude of pro-

C

oal mining in India carried a sym nationalised existence, and this exclusion grammes. Exclusion of women workers

bolic significance at one time. It has occurred at the lowest level – the from the coal mines, therefore, has a caste

represented the new modern numbers of white-collar office employees dimension.

economy that began to flourish in Bengal included in the official statistics on Cultural identities such as caste and

during the British rule. It fuelled the engines gender divisions of coal workers have ethnicity are inextricably intertwined in

of not only the Raj steamships but also the probably increased. Obviously, here is a India with class divisions, a fact that

Nehruvian model of postcolonial industri- problematic that needs looking into; put necessitated the rethinking of the assump-

alisation in India [Chakrabarty 1992] at a simply, who are being excluded? At whose tion of a singular, monolithic working class

high cost to the environmental and social cost? Where are the excluded women [Guha 1982-97; Chakrabarty 1989]. The

stability of these resource-rich regions. going? complexity that gender introduces in this

Like the plantations, collieries manifest The participation of local, poor, adivasi relationship have been brought into focus

almost all the symptoms of colonial and lower caste women in coal mining is by several experts [Fernandes 1997 for

modernity that descended on feudal eco- not comparable to the modes in which example]. Decline in the numbers of women

nomic relations and production systems: women in colonial Bengal were exposed workers in non-traditional roles outside of

private investment and the involvement of to modernity. In Kolkata, women of upper homes such as that as a miner in collieries

indigenous capital, import of labour from caste or elite families were learning with is an interesting problem to study; collieries

other parts of the country to build up a the patronage of both Indian and English are where women had at once interfaced

reserve of ‘captive labour’, a low level of social reformers, how to read and write, with men, with overlapping spheres of

technology, and its nature of a secondary and how to interact with men in spaces activities. From gin girls to scavengers has

enclave (described so first by Rothermund other than the domestic [Karlekar 1991; been a declining trajectory for the status

and Wadhwa in 1978) meant to serve the 1986]. At around the same time in Raniganj of women miners. Tracing that path brings

primary metropolitan enclave. collieries adivasi women were working out how the state and international agen-

The special feature of coal mining was shoulder to shoulder with men in com- cies, aided by a rigidly patriarchal state

the participation of women workers in the pletely different circumstances. Standing have worked together in defining a place

labour force, initially as part of a family noted (1991) that Bengali women, with the for women in a gendered resource economy.

labour system but also on individual ca- exception of a small professional group This place is at a lower level, secondary

pacity in later stages as certain castes (like from the upper class, have conventionally to the needs and struggles of men, in Indian

the bauris for example) came to be seen taken little part in waged work. The sepa- collieries.

as ‘traditional coal cutters’ by British ration of ‘ghar’ and ‘bahir’, the home and Mining is widely perceived as a uniquely

administrators [Paterson 1910]. Women the outside world, was so complete in male world where the separation of men

miners mostly came from adivasi1 and middle class, colonial Bengal [Chatterjee and women’s lives is virtually total

lower castes traditionally inhabiting [see 1993] that there not many instances of [McDowell and Massey 1984]. It is be-

Risley 1891 for more on the ethnic region- women working together with men as in lieved to be a dangerous, dirty, risky and

alisation in Bengal] this sal-forested jungle the collieries. On the other hand, the hazardous job in which men go down the

mahal tract of the Radh. Their roles in the exclusion that is taking place now some- mines everyday to earn bread for their

resource extraction process were signifi- what represents in a microcosm the post- families, endangering their lives, and

cant as long as the techniques remained colonial development scenario in which sharing risks that contribute to a particular

basic and labour intensive, and collieries the poor and indigenous peoples such form of male solidarity and also endow the

Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001 4213

manual labour with attributes of mascu- women clubbed together in official data now suffers from a chronic high un-

linity. The unequal economic and social as ‘women workers in the mining sector’. employment.

relationships between men and women Above all, I have described how the

imposed by the social organisation of marginalised poor adivasi woman has II

mining increase the subordinate position become invisible to policy-makers as the Coal Mines of Raniganj

of women in collieries both directly and absence of alternative means of livelihood

indirectly. in a viable environment has forced them Coal mining in India until independence

In this paper I am trying to understand into scavenging and hence turned them took place almost entirely in eastern India.

how the natural resource extraction pro- into illegitimate people. I emphasise that The history of coal mining in Raniganj,

cess becomes gendered in the first place, the increasing marginalisation of women particularly in the early days of the indus-

what happens when women find them- miners in the post-colonial or the post- try, is synonymous with the way modern

selves excluded from the mainstream nationalisation period has to be seen be- development has unfolded its trajectory in

economy, how difficult their survival yond the economic changes taking place India. Local folk tales tell of a river-borne

becomes in the face of a rapidly deterio- within the country or the industry. It has exchange trade of salt and coal between

rating environment denying them access to be put in the specific regional historical the Bengal plain and coast, and the Radh

to the basic resources, and how the pre- perspective and examined in terms of the region of Raniganj. However, the need for

vailing perceptions about men and changes occurring in that context. The fuelling the industrial-urban engine during

women’s spheres of work held by the exclusion of women miners and the trans- the British Raj and later a ‘planned’

International Labour Organisation (ILO), formation of the labour force into a economy of India actually gave rise to

the trade unions and the state create predominantly male, immigrant work- collieries. Raniganj, with its counterpart

gender polarisation at home and in the ing class represents a gender politics. Jharia in Bihar, had been the only supplier

workplace. This paper describes the exclu- National and international discourses of coal in India for about 100 years since

sion of women from the coal mining produced by the state, ILO and the trade coal was first struck by Suetonius Grant

industry in trying to unravel the relation- unions tend to conceptualise ‘the working Heatley and John Summer, two employees

ships between the various social, economic class’ as a unitary category transcending of the East India Company in 1774. They

and political factors operating in produc- both cultural and gender differences, worked on six mines, three of which were

ing this exclusion. and they juxtapose this unitary conception at Chinakuri, Aituria and Damodar – all

The research presented here was done to the ‘special interests’ of women work- located well within the Raniganj coalbelt.

over a period of seven years between 1993- ers to protect them from what they see as Initially the Company showed little inter-

2000 during which two other research a job for men. Marginalisation from the est in further exploiting the potential of

projects funded by the environment and formal sector also has a long-drawn coal mining in India [Akhauri 1969]. So

forests ministry, government of India, were impact on the livelihoods of women, as much was the reluctance that Heatley was

carried out on the region. These projects in mining regions the environmental per- even transferred – a rather common colo-

involved repeated and extended visits to formance of the India state has usually nial instrument of punishment – to a re-

the coal mining and other settlements in been abysmal. A deterioration and de- mote district to discourage his mining en-

Raniganj, meetings with the trade union cay in the subsistence resources even- thusiasm.

leaders, mine managers, workers and their tually denies basic survival opportuni- Coal mining in Raniganj remained spo-

families, and other local women. Repeated ties to the poorer women [Parpart 1995; radic in nature as long as it was not realised

interviews provided important insights into Venkateswaran 1995]. that instead of transporting British coal

women’s subjective experience of local- The research concentrates on a specific to India by steamships, it is economical

level environmental changes. Besides this region – the Raniganj coalbelt which is the to extract this resource in India itself

interview material, I have used historical oldest coal mining region located in the [Murty and Panda 1988]. This simple

information from printed sources avail- Burdwan district of West Bengal about economics generated much enthusiasm

able in libraries as well as with individuals. 250 km northwest of metropolitan Calcutta. in opening new collieries at random. The

Statistics from census reports were con- Mining in this old colliery region is still British emerged as the main investors

sulted as well as data from Eastern almost the only livelihood provider among when by the second part of 19th century

Coalfields Limited (ECL) and Coal India many dying industries, overcrowding, coal mining picked up in the region.

Limited (CIL) – the government compa- decaying agriculture and severe environ- Transport to the main market in Calcutta

nies in charge of mining in the region – mental problems such as land subsidences was difficult as it depended on the Damodar

and other actors in the industry such as and surface and subsurface coalfires. It and Ajoy, both seasonal rivers with low

directorate general of mines safety (DGMS) has a high level of urbanisation – above navigability and tendency to monsoonal

and the trade unions. 67 per cent of its population live in some flooding. The name ‘Koilaghat’ (coal

Official data usually club all women in 38 mining towns and other urban centres point) in Calcutta strand still testifies to

the industry as one group leading to prob- of various sizes [Lahiri-Dutt 1996]. The coal transport by rivers from the Raniganj

lems of understanding the nature of their region received massive government region.

jobs; so it was not of much help. In coal investments since the Second Five-Year Three factors provided the initial stimuli

mining, as I have shown here, a specific plan period and there were hopes that it for growth of coal mining industry – the

group of women participated traditionally; would be transformed into ‘the Ruhr of abolition of East India Company’s trading

exclusion means these women are being India’ [Chaudhuri 1971]. However, none monopoly in 1813; opening of the Raniganj

denied a role in the production process; of the industries set up by the government mine under European supervision; and the

not the urban, educated, middle class has been quite successful and the region introduction of railways in 1855 [Munsi

4214 Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001

1980] to facilitate coal transport to the collieries) had the largest number of women Indian Mines Act, initiated first in 1901,

market in Calcutta. miners. restricted the age of employment of chil-

By the time of Hunter’s famous visit to dren in mines. In 1929 and finally in 1935

the region it was ‘practically treeless’ III the Mines Act entirely prohibited com-

[Hunter 1872, reprinted in 1973], and a Gin Girls pany owners to employ women in under-

change in the region’s social fabric had ground work. Such orders were issued

become notable. Indigenous entrepreneurs The term ‘gin girls’ reminds one of a again in 1946, and then a complete ban

eventually came to dominate coal produc- technology of coal production that existed in 1952 that stated that women miners will

tion; as many as 13 of the 17 companies in the early days of the industry. Till the be employed only in surface work during

were owned by Indian operators in early early part of 20th century, shafts were the day shifts [Coal Handbook 1997].

part of the 20th century [Bhattacharyya sunk every few hundred feet and quarries These acts restricted the period of work

1985]. Prince Dwarkanath Tagore’s Carr, were often opened below the high water from 16 to 12 to 10 and eventually 8 for

Tagore and Company was merged with mark whenever an outcrop was found near underground workers and 9 for surface

Gilmore Humfrey and Co to form the a waterway. The mining appliances, tools workers. The acts/measures were presented

Bengal Coal Company that soon became and methods were simple. For example as a means of ‘protecting’ women from

the largest operator. In 1860, the 50 coal was brought from the face to pit bottom an unsafe job such as mining. The state

collieries of Bengal Coal Company pro- in head baskets, usually by women. There assumed its traditional benevolent role

duced 99 per cent of Indian coal. The low it was put into larger baskets (6-7 maund through its commitment to the protection

levels of technology and capital invest- or about 250 kg) and wound to the surface of women. The legislation tell us that

ment ensured that local zamindars2 could by a winding engine, called a ‘gin’ (an women miners were perceived by the state

make an easy entry into the industry abbreviation also used in other industries as one group that needs to be ‘protected’

[Rothermund and Wadhwa 1978]. As mine such as cotton). Women worked the ‘gins’, from the hazardous mining work. However,

owners concentrated on underground re- sometimes in groups of more than 20. they had the impact of reducing women’s

sources, and left the surface cultivation Small ‘beam’ engines were occasionally work participation; in 1901 women formed

rights to local people, there were fewer employed to do the combined work of about 48 per cent to total mineworkers in

conflicts with agriculture than at present, pumping and winding and were manned Raniganj. Of these women, 65 per cent

and instances of displacement from land- by three women. Steel tipped curved pieces worked in underground collieries. The

based occupations were fewer. of iron were used as picks with blunt proportion remained more or less the

The land laws of India gradually began wedges and hammers and one inch round same till 1921 (38 and 60 per cent on

to change so that the mining companies crowbars. surface and underground, respectively).

started to gain control of both surface and Around 1920s, women miners were The proportion of women miners decreased

sub-surface rights of the land as operations employed in a variety of operations in from such high levels to around 20 percent

became much larger in size in the early collieries. As steam engines ‘phased out’ in postcolonial India.

20th century [Manindra 1946]. As long as gin girls, and collieries came to be owned The data in Table I show that the par-

coal mining was ‘extensive’ in nature, by Indian entrepreneurs, women ended up ticipation of women in collieries was

technology did not undergo any decisive working as kamins on surface as well as somewhat significant till about 1930s.

changes, the units of production did not in underground mines. However, eventu- The second world war provided exigen-

grow in size, and mines of similar size ally women workers got large-scale em- cies that forced the mining companies to

were added to each other to increase pro- ployment as ‘loaders’ who lifted and trans- flout these acts/measures and women

duction, women miners continued to take ported the coal cut by their male partners continued to be employed in large num-

a significant role in the industry. – father, brother or husband [Roy bers in production to meet wartime de-

The coal mining industry was brought Chaudhuri 1996]. This ‘family labour’ mands. However, the net effect was that

under state ownership in several phases system was suitable in view of the primi- women became ‘unofficial’ employees, as

during 1971-73 [Kumarmangalam 1973]. tive techniques used in the shallow open there are very few quantitative data avail-

The private owners were given compen- cast mines, locally called ‘pukuriya khads’ able on their participation during this time.

sation and expelled from ownership, but as well as the inclines. The period between 1947-71 is another

the labour relationship they had instituted The technology of coal production in hazy area with regard to official statistics;

continued in the collieries. All minerals India began to change in response to greater

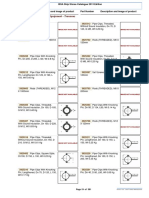

were classified into two categories – major demands by 1920s. This meant the re- Table 1: Proportion of Women Workers

in Eastern Indian Collieries(1901-96)

and minor, and all major minerals includ- placement of open cast mines by deeper

ing coal were brought under state control. shafts, which were considered ‘unsuitable’ Year Female Male Percentage of

Female to Total

India is now the third largest coal producer for women. This technological shift and

of the world with an annual production of resultant exclusion of women workers took 1901 26,520 55,682 47.6

place at several scales; at the international 1921 70,831 115,982 61.1

about 299 million tons which is about 68 1935 67,899 122,454 55.5

per cent of total energy resources of the level by several ILO measures – the 1919 1951 45,668 128,936 35.4

country [Coal 1999]. The entire coal mining Convention on Night Work (Women), the 1961 41,457 134,928 30.7

1973 31,181 138.587 22.5

industry was put under the umbrella 1935 Convention on Underground Work 1980 16,094 169,136 9.7

organisation Coal India Limited (CIL). Of (Women) – restricted women workers from 1990 12,875 165,829 7.2

its several regional subsidiaries, the working in both shifts and from working 1996 9,879 151,855 6.1

collieries of the Eastern Coalfields Lim- in underground mines [ILO 1999, 1997, Source: Compiled from Seth (1940), DGMS and

ited (ECL, controlling the Raniganj 1996, 1988]. At the national level, the ECL Reports.

Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001 4215

this was the period of ‘company’ raj when 1999a]. The new technologies have not William Jones, one of the British entre-

local and non-local entrepreneurs had re- been developed indigenously. Many of preneurs to invest in coal mining, was the

placed local zamindar-owners in many the newly opened mechanised mines are first to employ local adivasi and lower

Raniganj collieries. The feudal relation- usually worked with foreign assistance – caste labour around the middle of 19th

ship between labour and colliery-owners both financial and technical. The conven- century. So easily were they absorbed in

was transformed into a more cash-oriented tional board and pillar system of mining their new occupations that the British

relationship, and the mining companies’ still accounts for 95 per cent of the un- administrator of Burdwan district, Paterson,

primary objective became to increase derground production in Raniganj. With reported in 1910 in the Imperial Gazetteer

production at any cost to supplement the such developments as shaft-sinking techno- that two-thirds of the total workforce in

industrial dreams of planned development logy, deployment of longwall and other the mining industry was ‘locally born’. Of

of modern India. heavy capital equipment underground, the different local adivasis, the bauris were

The image of the coal worker invoked and the introduction of dragline-based the first to bring their women into the

by both the state and trade unions is in- open cast mining, women have been as- collieries and their contribution in the early

variably a masculine one. Women have signed mostly unskilled tasks, whereas development of Indian coal mining indus-

become invisible, persona non grata in the there has been no attempt to impart train- try was quite significant. The santhals,

coal mining industry. Their role has de- ing and skills so as to enable them to kols, koras and bhuinyas also joined the

clined at an alarming rate during the last adjust to the reorganisation of work. Women mining workforce along with their women.

two and a half decades under the state- now occupy a marginal position in the These are the people that are at the bottom

ownership of coal mining industry. During Indian coal industry because they have of a caste divided society – mostly lower

this period the Indian coal mining industry been made redundant in the labour process caste groups and adivasis who were being

has been characterised by two trends – [Ghosh 1984]. sucked into the mainstream colonial

increasing mechanisation to improve pro- economy and society through the coal

duction through technologies such as IV mining industry. Upper caste women

dragline and shovel for the open cast mines Family Labour and Women usually stayed away from the colliery work.

and longwall for underground mines, and Women of different local castes and

increased thrust on open cast mining to When Heatley opened his first mine communities participated in varying pro-

compensate for what CIL perceives as loss- in 1774, he had invited experts from portions in coal mining as seen from

making underground mines [Lahiri-Dutt England besides employing the local labour. Table 2.

Civic Professionalism and Global Regionalism:

Justice, Sustainability and the ‘Scaling up’

of Community Participation

Rockefeller Humanities Fellowships, 2002-2003

University of Kentucky

The Appalachian Center and the Committee on Social Theory of the University of Kentucky

announce a three-year program of resident fellowships on globalization, democracy, equity

and sustainability. We are particularly interested in scholars from the global South —

especially Asia, Latin America, Africa, Pacific rim.

Deadline is February 1, 2002 for applications for fellowships in 2002-2003.

Application materials can be found on the UK Appalachian Center website

www.appalachiancenter.org or contact: Nyoka Hawkins, (859) 257-8265,

nyoka@pop.uky.edu, Appalachian Center, University of Kentucky, 624 Maxwelton

Court, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0347 USA. Tel: 859-257-4852. Fax: 859-257-3903.

4216 Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001

To British visitors A A Purcell and J period never to come back. Paku Mejhen, century proves the fact. It also indicates

Hollsworth (as mentioned in Sinha, 1975) whose Santhal adivasi ancestors had lived how changing techniques of production as

such family labour systems appeared en- in the region for generations, remembers well as changing production relations

tirely ‘different’ from that ‘in our collieries’ how ‘Bilaspuris’ and ‘Gorakhpuris’ (labour altered the social-ethnic composition of

where miners had already organised as an from Bilaspur in Central Province and labour in collieries. When the state itself

industrial working class. Collectively, Gorakhpur in north India) were brought in became the owner of resource extraction,

Indian coal miners still had rather strong to work in collieries and kept in ‘labour its labour policy did not undergo signifi-

traditional rural roots and occupational depots’. The manager used to send the cant changes from the ‘company’ owners.

loyalties. The local adivasi and semi-adivasi sardar (leader of workers, a foreman) to Trade unions – there are at least six

labour often used to leave the collieries a depot to get a few additional hands as recognised unions operating in the Raniganj

during the rains to work in the agricultural soon as there was a labour shortage. The region now – were delighted at the time

fields, and this interfered with mining CRO received commission from the com- of nationalisation but they too soon settled

operations. In addition, there was the panies in return of labour supply. in their new role of bargainer with the state,

adivasi’s love for freedom (that is often Gorakhpuris, of course, began to perma- apparently oblivious of subtle nuances of

not mentioned in such studies, for ex- nently live in Raniganj as working con- caste and gender in the workforce.

ample, see Read, 1931). In spite of work- ditions began to improve in post-colonial There are many accounts of coal mining

ing as miners, the adivasis never allied times when trade unions began to wield in Raniganj in colonial records. One such

with the British in the empire building their full weight. Paku calls each coolie was written in 1915 by Colond Frank J

project and hence periodically withdrew dhaora by its cultural name even now; to Agabeg, the general manager of Apcar and

from collieries. her it is always a santhal bastee, kora, Company, the pioneering coal mining

The family system of labour operated nunia, Gorakhpuri or a Central Province concern in the Raniganj region. He de-

well for several social reasons too – the (CP) dhaora. Most of the adivasis, how- scribed how Asansol, now a major urban

adivasi sentiments of family attachment, ever, responded to the import of migrant centre, had then just started to develop

and the unwillingness of women to carry labourer by leaving the collieries to work and Raniganj was the most important

coal for men of another caste. Above all, in plantations in North Bengal or Assam. mining town. Barakar town was the western

the dominant economic reason was that Gradually a large segment of the workers terminus for the East Indian Railway,

it provided uninterrupted maintenance in the collieries become typically immi- whereas Ondal had a large railway siding.

of work schedule. Trade unions believe grant and male, caste Hindus from north Collieries located at a distance from the

that the system was an exploitative one; or central India. Some adivasi women like railway transported their coal by bullock

as women as one single unit of production Paku’s grandmother still carried on, though carts across dirt tracks. Only those adja-

did not receive equal wages to men. their contribution in the resource extrac- cent to the railway lines had sidings for

Collieries began to employ ‘upcountry tion process was increasingly being deval- loading and unloading of coal. The cost

labour’ (normally originating out of two ued in more ways than one. of such infrastructure construction was

simultaneous migrations – one from the Another major factor of the exodus of borne by the companies themselves. The

western districts of Bihar, Gaya, Patna, adivasi labour was the introduction of Bengal-Nagpur Railway eventually ex-

Sahabad, Saran and Muzaffarpur while new technology. The changeover from tended the subsidiary lines to the less

the other from the adjoining eastern opencast and inclines to shaft or pit mining accessible collieries and thus an intricate

districts of United Province – later Uttar after 1920s required far greater initial network of ‘company lines’ grew up in

Pradesh – such as Azamgarh, Balia, capital investment and consequently, the Raniganj.

Ghazipur, Benaras, Jaunpur and Bilaspur) interests of the colliery owners to secure What was the view from below? Paku

to create their own captive workforce. a stable and skilled labour force grew con- describes the hierarchical colliery life which

Thekadars (contractors) brought hard- siderably. In the capitalist production placed women workers like her great

working able-bodied males from eastern process that collieries adopted, local grandmother at the bottom:

Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and even Madhya adivasis with their first commitment to In the colliery, managershaheb was the

Pradesh. Intra-state voluntary migration land were not considered by mine-owners boss. Borobabu was under him, translated

was initially comparatively smaller in as a stable and dependable labour force. his instructions and in case of any trouble

volume, possibly due to the ravages left However, instead of encouraging the dis- controlled the situation. The manager-

by frequent bargi (Maratha raiders) attacks sociation of land and labour, the ‘compa- shaheb would shout, ‘borobabuko bulao’

from the western states of India [Guha nies’ tried to maintain a semi-feudal

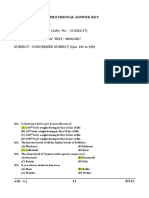

1955]. A statutory body called the Coalfield zamindari style of functioning, and adopted Table 2: Ethnic Division of Women

Recruiting Organisation (CRO) was intro- a recruitment policy with the objective of Miners in Raniganj, between the Wars

duced to maintain, often forcibly, the supply offering a homestead to captive labour

Castes Women/100 Castes Women/100 Men

of labour to the mines [Mahindra 1946]. supply. The colliery workers, like other Men of Their of Their Caste

Tales of how labourers were kept in chains rural-based workers in Indian industries Casts

in the coolie-barracks have now become (see for example, De Haan and Sen, 1999 Doms 111.0 Kurmis 67.5

part of the folklore in Raniganj. Work was for more discussions on the cultural Jolahs 59.4 Bauris 55.8

at least for 12 hours and cash wages could rootedness of industrial labour force in Mallahs 79.5 Rajputs 27.2

never compensate for a kind of work that Bengal) neither economically nor ethni- Beldars 102.0 Goalas 24.5

these agricultural people could never cally belonged to the same class. The Santhals 87.9 Telis 45.5

Bhuiyas 80.1

identify with. Many of the upcountry labour withdrawal of adivasi labour from Indian

left the mines after their 11 month contract collieries during late 19th and early 20th Source: Seth (1940), p. 129.

Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001 4217

(call the borobabu)! Gomostababu man- has in several ways excluded them entirely However, the trade unions have remained

aged the coolleys and kamins, gudambabu from the power to determine their own insensitive to either the declining numbers

looked after the store, hazribabu took lives. Three factors have contributed in the of women workers in collieries or the fact

attendance, loadingbabu supervised coal differential gender impact of coal produc- that this exclusion means a certain group

loading, and batibabu distributed the lights. tion: gender segregation in the workplace, of women are left out. As institutions they

We santhals did all the dirty and heavy jobs the less secure and more sporadic forms are male-dominated and, while some trade

– our men cut the coal and women loaded of employment relations which exist for unions have added women-related is-

it in baskets. We grew up on collieries; in women workers, and the very nature of sues to their ‘list of workers’ demands’,

our family my great grandmother was the technology as a social relation which is their policies have not placed women at

first to go into the khadan with my great

necessarily conditioned by gender rela- the forefront of these agendas. Women

grandfather.

tions. Women still participate in mining, workers are thus excluded at the level of

Later, more babus (clerks) came to including coal mining, in India and else- leadership and policy, and even if women

occupy middle-positions between the where in the world, but their roles remain are members they are discouraged to

malkata (coal cutters) and the manager in significant as long as the resource process participate in union meetings. The belief

collieries. The bijlibabu for instance ap- remains low-technology. In the Raniganj in a monolithic working class is shared by

peared with the advent of electricity in region, the introduction of underground all trade unions whether leftist or not,

collieries before the second world war. mining restricted women to surface work, subsuming gender issues within class in-

So came compassbabu (surveyor), machines restricted them to unskilled work, terests. This is neither surprising nor

miningbabu and inchajbabu (in-charge). the process of mechanisation generally unusual; McDowell and Massey (1994)

This structure has remained more or less reduced their opportunities in the coal have showed how in the colliery settle-

unchanged till now excepting the fact mining sector, and a degraded environ- ments of Durham, England, gender seg-

that some white collar jobs have come ment truncated the alternative subsis- regation in the coal mining industry had

up for women in colliery offices. Men now tence bases in agriculture, forestry, fish- led men to view themselves as industrial

operate the machines that have replaced ing and such other primary productions proletariat but enjoying the ownership of

women workers from surface and under- which have traditionally provided em- their home.4

ground jobs, and there have been very few ployment to local women. Union activity in India has been de-

attempts to impart technical skills to the Sitting in her ‘rehabilitation’ home Aduri scribed as being shaped by a gendered

woman who enters the collieries as ‘com- Ruidas, an evictee, a person displaced by discourse that looks at women as a ‘spe-

pensation’ cases after the death of the the World Bank-aided large open cast cial’ category externalised from the gen-

husband. project at Sonepur Bazaari, was talking to eral interests of workers [Basu 1992]. In

me. She explained in a few words how a Raniganj too, the Colliery Majdoor Sabha

V woman becomes a scavenger. takes pride in their mass movements and

Into Scavengers: Women and When the mining company takes the land how women ‘participate’ in these move-

Resources on lease, it pays compensation to the owner ments, but it never goes beyond that. The

of the land, and gives them jobs too. No active participation of women in leading

Each change in production technology one pays attention to what happens to or key roles in trade unions has not always

within the industry also had a gender people like us who had worked on that been welcomed by male trade unionists in

impact: the changes effectively excluded land. Who collected the twigs and branches other sectors [Akerkar 1995]. Mining is an

and marginalised women, the extent of ex- and fruits from the bagan (orchards)? Who overwhelmingly male world in terms of

clusion depending on how men’s interests, used the ponds for our daily water needs? power and domination; men are perceived

needs and hopes are disproportionately Not only the owner of the land but we too. to be risking their lives to earn the bread

represented.3 Therefore, the impacts of What will happen to us? What use do have for their families. Labour leaders are

technology changes have been experienced of a brick house? Shall we eat it? vociferous that the family wage system

differently by women than men in collieries. The trade unions have come a long way was more exploitative; but generally refuse

Since much of these changes was not in the Raniganj region from the old days to engage in a debate on the declining

autonomous and used indiscriminately of long working hours, lack of security and numbers of women in the collieries. A

without paying attention to its suitability frightful conditions as described by Dange senior union leader noted during an inter-

to the region [Lahiri-Dutt 1999b], they (in 1945). They have indeed earned for the view: ‘in a poor country like ours, let men

have failed to stimulate other sectors of workers many benefits they presently enjoy, get the jobs first’, reflecting the conven-

the regional economy. On the other hand, and have in turn made getting a job in tional wisdom that since ‘important’ eco-

the obsession with the import of techno- collieries a highly attractive proposition – nomic problems such as mass labour

logical input has had major impacts on the far better than what was described by the retrenchment, mine closures and losses

regional environment and destroyed the government of India in a 1967 survey due to lack of productivity are intense, a

natural resource bases and the livelihood report on labour conditions. Instead of debate on the position of women workers

sources of poorer, rural communities. The treating ‘family’ as a unit of production can only be of secondary significance.

absence of opportunities in other sectors to devalue women’s work, trade unions Women’s right to work is also compro-

of the economy in mining regions such as have earned equal wages for women and mised by the voluntary retirement scheme

Raniganj, especially the loss of commons men in mining work. Ensuring that a widow (VRS) which is used to get rid of ‘redun-

and the decline in agriculture, have further gets the job of her deceased husband on dant’ workers.

affected women. In Raniganj, women’s compassionate grounds was also the In India the displacement of women from

banishment from the male world of ‘work’ achievement of trade unions. the industrial workforce and the subse-

4218 Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001

quent construction of a male working class do not protest about the union’s reluctance ration of ‘home’ and the ‘workplace’ is

has not been limited to the coal-mining to entertain them, she said, “we are always now complete in the Raniganj collieries.

sector only. Jhabvala first showed in 1985 ready for action, but first think before Women are protected within the family,

how retrenched women workers from shouting. If the leaders are enraged, we work being a mode of access to a public

cotton mills of Ahmedabad in west India will be in big trouble. So we keep quiet”. space, a forum for combative actions to

were pushed into lower paying and inse- When I probed further, she said, “Look ensure equal rights. But are they, in reality?

cure jobs. Banerjee (1991, 1992) too noted at Prakashbabu (the local trade union What happens after they have been pro-

the lack of political protection of women leader) – he is just like other babus in tected from the dirty, dangerous mining

by unions. Baud (1991) has demonstrated colliery. How can he look after my inter- jobs?

that in case of women workers in the est?” What we have here is a double dose

Coimbatore textile industry in south India, of exclusion, and a chain reaction of impacts VI

gender segregation is most marked in the that multiply and accelerate to immense Changes in Resource Base

mill sector where regulation and trade union proportions. and Gender

activity is more evident. In coal mining Not surprisingly, the only patronising

too, trade unions are less responsive to initiative came from the establishment Mining by its very nature is an unsus-

women workers than their male members’ itself. In 1997, Coal India encouraged the tainable activity from the ecological point

interests. The attitude to the women workers formation of an organisation called of view. Mining in India is also unsustain-

is condescending and in their ‘noble’ efforts ‘Women in Public Sector’ (WIPS) with the able economically; if environmental costs

to ‘protect’ the weak women, the trade objective of optimising the full potential are taken into account, even the most

unions often fail to look after women’s of its women employees and to play a productive of mines would not seem ter-

issues and interest in a substantive way. catalytic role in improving the status of ribly attractive. That in spite of the exist-

Fernandes (1997, 1999) has shown how women. However, the organisation is a ence of innumerable laws and measures to

the politics of gender, class and culture city-based one with white-collar women monitor, mining in India completely alters

produces notions about the spheres of workers. It has so far limited itself in holding and destroys the local ecology has been

work of women and men in Calcutta jute academic seminars instead of establishing proven by innumerable studies [see Dhar

mills. a dialogue with the trade unions and the and Thakur 1995 for a sample]. The overall

There is not much organised activism colliery management. Women miners who environmental impacts of mining are

among the women coal miners; protests work in collieries are not represented at uniformly detrimental and its human con-

remain small, at individual level and all in this organisation. Moreover, the sequences especially in terms of displace-

discontinuous. Political silencing remains mining industry has so far not taken any ment of social groups either from tradi-

an important factor because of the serious initiative to identify the technical tional homes or from traditional occu-

organisational strength of the majdoor job areas where women could be employed pations leave much to be desired. The

unions. The militancy of the trade unions, or trained. changing subsistence base constitutes

at least three of them being avowed Marxist The state measures reflect a compart- another driving force behind the transfor-

organisations, is understandable. The way mentalisation of the issue of women miners mation of women’s lives in Raniganj. Such

the unions perceive their jobs is significant [Gibson-Graham 1994]. The various pro- changes often have negative effects on

too; the term ‘majdoor’ itself denotes a tective legislation developed for women women from the point of view of alterna-

male worker and the occasional cases that miners, though probably designed to tive work in a degraded environment

are taken up are indeed seen as special improve their working conditions, have [Emberson-Bain 1994; Shiva 1989; Jose

ones. Dulali lost her husband in a wall- acted as instruments to exclude them from 1989; Tauli-Corpuz 1988]. An entire range

collapse accident and applied to the com- the formal mining sector. The nationalised of issues are, therefore, connected to the

pany for her own employment. Here is company has been unwilling to recruit exclusion of women from resource extrac-

what followed in her words: women because of their special and pro- tion activity – the state and the rights of

I made rounds of colliery offices for two tected status on the one hand, and on the indigenous people, state policies regard-

years. Finally I went to the union leaders other hand the legislation has not included ing land transfer, and the rights of local

who insisted that I accept that my elder any means for the protection of employ- communities over environmental and

son may be given the job. Following ment opportunities and job security. Thus common pool resources.

their advice, I decided in favour of my the special biological attributes of women In Raniganj, the state (through the

son and now I hardly get two square meals have been at the centre of concern by the nationalised mining company) is the

a day. ‘protectors’ rather than against discrimi- largest landowner and the largest employer,

Her son has now deserted her and she nation due to cultural, social and economic besides having the ownership of all natural

lives by what she describes as ‘collecting factors [Pathak and Rajan 1992]. As a resources within its territory. As the pace

coal’ from an old abandoned mine. The result, women of those ethnic groups of coal mining increased since 1970s,

company, supposedly had stowed the that traditionally did mining jobs – usually open casts expanded and newer collieries

underground mine with sand and sealed the most disadvantaged of the lot – have opened, a rapid rate of ecological destruc-

it off. Now local people have broken off been most affected than white-collar tion took place. The specific historical

the seals and, finding that much coal is still workers. pattern of mining expansion in the Raniganj

left there and no sand has been stowed, The exclusion of women miners brings meant that there are innumerable under-

are scavenging on it. Dulali is one of them. out how an ideology of ‘protection’ con- ground voids at unknown locations.

After deliberating in her mind for a long tinues to dominate women’s active role in Since it is a densely populated and

time when I asked why women like her natural resource management. The sepa- urbanised area, land subsidence, coal seam

Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001 4219

fires, desiccation of vegetation and a less decayed over the last two and a half ‘untouchables’, in their study arguing that both

falling water table are the main environ- decades under state-ownership of the harijan and dalit are more political names

for a creature whose identity continues to

mental concerns. These are related to live- collieries. Much of the cultivation that be rooted in the concept of ritual pollution that

lihood resources of women of poor rural one sees is actually on colliery-owned is itself a part of a very elaborate theology of

communities. land and is again another form of ‘illegal’ the pure and the impure. I have used adivasi

What is seen here is a classic example activity like the scavenging for coal that throughout this paper to mean the scheduled

of feminisation of poverty, when ‘deve- goes on in old abandoned underground tribes of the region as identified by the

lopment’ itself brings about that poverty and open cast mines, and on privately Constitution of India.

2 The zamindars of Burdwan unlike those of the

[Lebra, Paulson and Everett 1984; owned land. other districts, survived with an amazing degree

Mazumdar 1978]. Rural women in The past two decades have seen a global of resilience and was able to make the

Raniganj have traditionally found employ- rethinking on what constitutes ‘develop- changeover from the old zamindari system to

ment in agriculture-related jobs. A decay- ment’. In coal mining in India, develop- the new order commonly known as permanent

ing agricultural base and falling ground ment is state development. As the bound- settlement and introduced by Lord Cornwallis

in 1793 with but a few cuts and scratches.

water tables, lack of wood, fuel, fruits aries between public and private spheres, While other zamindars also played the same

and other subsistence resources which of cash/wage work and family/household, game, the Burdwan raj initiated the process,

were usually collected from the village are created or redefined in the course of almost perfected the structure before others

commons, and near-absence of oppor- development, what are the implications for could even collectively conceive of it. Therefore,

tunities in this mono-industrial region women in the resource process? What is the Burdwan raj model of subinfeudation under

permanent settlement has been described as sui

have combined together to completely the role of the state in defining the chang- generis, the best specimen, the leading species

alienate poor adivasi and lower caste ing boundaries between public and private of what developed to be a large genus

women from the formal mining sector. and how susceptible are these boundaries [Bhattacharyya 1985]. Major changes kept

This sector absorbs women at the lower- to state control [Charlton, Everett and taking place in Burdwan region during the 19th

most strata in low-paying jobs such as Staudt 1989]? We saw that for women century: a rise in the production, prices and

manual labourers in the construction works, miners the enhancement of state control exports of foodgrains; in the rentals; in

production, prices and exports of each crops;

various small factories, brick-kilns, stone- over mining has not offered greater oppor- tenancy legislation; coal mines; railways

crushing units, as rag-pickers and as do- tunities than before. We have also revealed expansion and growth of the market in general;

mestic help, as sex-workers catering to the contradictory positions of the Indian expansion and growth of the market centres;

truck-drivers, and as workers in the flour- state with regard to gender relations in and decay of river-borne trade bringing down

ishing unauthorised coal mining and trade. collieries. Through its laws of protection a set of older settlements along it with the rise

of railways and new urban centres.

The family is no longer a valid unit of and welfare, and then exclusion from 3 It is strange how mining is commonly seen as

production; the family and the factory are livelihood bases, the state simultaneously a heavy, masculine job whereas in reality women

of no consequence to each other, and may reproduces and endangers the gender- have done the manual jobs more efficiently

even have contradictory interests. The result based division of the public and private than men. In post-industrial Britain for ex-

is a lowered, powerless status for women spheres. In this way contradictions and ample, Reverend Eddy (1854) gave a vivid

description where women stood or doubled,

who continue to get drawn to the main- inconsistencies in respect to gender

often in knee-deep water, in deep and thin

stream mining-urban-industrial economy issues become ingrained within the nature shafts of collieries: ‘females submit to labour

at the lowest level as unskilled, low-paid, of development. -29 in places which no man, or even lad could be

high-risk, illegal workers, while taking the got to labour in; they work in bad roads, up

full brunt of environmental degradation Notes to their knees in water, in a position nearly

[Lahiri-Dutt 1999c]. double; they are below till the last hour of

[A previous version of this paper was presented pregnancy; their limbs and ankles swell, and

Rothermund and Wadhwa (1978) noted as a Working Paper at the Resource Management they are prematurely brought to the grave, or

a decline of agriculture albeit of a different of Asia Pacific Project, Research School of Asia what is worse, a lingering existence.’ A 16-year

type at pre-nationalisation times – Pacific Studies, The Australian National old girl working as windlass woman is quoted

zamindars squandering money, inter- University, where I was a Visiting Fellow. I thank by Reverend Eddy as saying: ‘we wind up eight

mediaries and moneylenders benefiting these institutions for giving me an opportunity to hundred loads (a day). Men do not like the

explore beyond the disciplinary space of winding. It is too hard work for them.’ How-

from the wealth derived from agriculture, Geography. I deeply acknowledge my intellectual ever, the self-congratulatory public outcry

and the peasant at the subsistence level debt to Katherine Gibson, professor of Human that followed in Britain resulted in a double

unable to produce enough food for Geography, at The Australian National University. hardship for women as they were thrown out

market transactions. In the last three She suggested the title of the paper and many other of employment. Once again petitions were

decades of rapid expansion of mining a changes, that I hope to have incorporated. Closer placed that women may be restored to the

home, I would like to thank Sunil Basu Roy and privilege of working in the mines that they

decay in agriculture has began to ravage Haradhan Roy of Asansol and Raniganj towns,

the region’s poor peasantry, a decay re- might not starve. The net result of all this was

respectively, and Mr Joydeb Banerjee of Eastern that working conditions for women were not

lated to environmental impacts of wide- Coalfields for sharing with me their vast knowledge much improved, but they entered the mines

spread mining and inadequate policing by about the collieries of the region and its workers. more subdued, more at the mercy of the owners,

the state in enforcing good environmental In the department, I would like to thank Ms Ira more voiceless.

Ghosh for her assistance.]

practices. However, the deterioration of 4 That women and men are treated differently by

the natural resource base has affected even 1 I prefer to use the term adivasi meaning original trade unions is not quite uncommon. In

inhabitants over other names for subaltern Australia, for example, women workers formed

those rural women who were never di-

groupings of indigenous populations of India their own unions as early as 1912. The Harvester

rectly engaged in coal mining industry. that include tribals, untouchables, dalits and judgment there was a landmark judgment, which

Agriculture, the traditional activity that harijans. Recently, Mendelsohn and Vicziany fixed the wage for women at 54 per cent of the

women could fall back upon, has more or (1998) have retained the original term, basic male wage. The basis of this was the

4220 Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001

concept of ‘family wage’ – the notion that men British Mines’, Ladies Repository, Vol 14, No Structure of Mining Towns of West Bengal’,

had to support wife and children whereas women 7, pp 295-98. Urban India, Vol XVI, No 1, NIUA, New

had only themselves to support. This had Emberson-Bain, Atu (1994): ‘Mining Delhi, pp 107-20.

established women as a form of cheap labour Development in the Pacific: Are We Sustaining – (1999a): ‘State and the Market: An Analysis of

but at the same time given them an ‘unfair the Unsustainable?’ in Wendy Harcourt (ed), the Crisis in the Raniganj Coalbelt’, Economic

advantage’ [Metcaffe 1987]. As female labour Feminist Perspectives on Sustainable and Political Weekly, Vol XXXIV, No 41,

becomes cheaper, employers respond by trying Development, Zed Books, London. pp 2952-56.

to define more and more work as women’s Fernandes, Leela (1997): ‘Beyond Public Spaces – (1999b): ‘The Promised Land: Coal Mining and

work. Male trade unions in turn defend their and Private Spheres: The Politics of Gender, Displacement of Indigenous Communities in

interests by trying to have women expelled Family and Community in the Calcutta Jute Eastern India’, Asia-Pacific Journal on

from most areas of employment. Mills’, Feminist Studies, Vol 23, No 3. Environment and Development, Vol 6, No 1,

– (1999): ‘Displacing Women Workers on the June 1999, Bangladesh Unnayan Parishad

References Margins of Working Class Politics in the Jute (BUP), Dhaka, pp 31-46.

Mills’ in Arjan de Haan and Samita Sen (eds), – (1999c): ‘Gender Inequalities in the Mining-

Agabeg, E C (1915): ‘Labour in Bengal Coalmines’, A Case for Labour History, K. P. Bagchi and Industrial-Urban Economy of the Raniganj

Transactions of the Mining and Geological Company, Calcutta, pp 176-96. Coalbelt of West Bengal, India’ in Graham

Institute of India, Vol VIII, Calcutta. Ghosh, Anjan (1984): ‘Escalating Redundance: Chapman, Ashok Dutt and Robert Bradnock

Akerkar, Supriya (1995): ‘Theory and Practice of Dispensability of Women Labour in the Coal (eds), Urban Growth and Development in

Women’s Movement in India: A Discourse Mines of Eastern India’, Paper presented in Asia, Volume II: Living in Cities, Ashgate

Analysis’, Economic and Political Weekly, EIWIG Conference on ‘Women Technology Publishing, England, pp 167-76.

Vol. XXX, No. 17, April 29, pp WS2-23. and Forms of Production, Madras, October Mahindra, K C (1946): Indian Coalfields

Akhauri, R K (1969): Labour in Coal Industry 30-31. Committee Report, Manager of Publications,

in India, Sterling Publishers, New Delhi. Gibson-Graham, J K (1994): ‘ “Stuffed if I Know!”: New Delhi.

Bannerjee, Nirmala (1991): Indian Women in a Reflections on Post-modern Feminist Social McDowell, Linda and Doreen Massey (1984):

Changing Industrial Scenario, Sage, New Delhi. Research’, Gender, Place and Culture, Vol 1, ‘Coal Mining and Place of Women : A Case

– (1992): Poverty, Work and Gender in Urban No 2, pp 205-24. of Nineteenth Century Britain’ in Doreen

India, Centre For Studies in Social Sciences, Government of India (1967): Report on the Survey Massey and John Allen (eds), Geography

Calcutta. of Labour Conditions in the Coal Mining Matters! A Reader, The Open University,

Basu, Amrita (1992): Two Faces of Protest: Industry in India, New Delhi. Cambridge.

Contrasting Modes of Women’s Activism, Government of West Bengal (1997): Coal Mendelsohn, Oliver and Marika Vicziany (1998):

University of California Press, Berkeley. Handbook, DM’s Office, Burdwan. The Untouchables: Subordination, Poverty

Baud, Isa (1991): ‘In all its Manifestations – The Guha, R (1955): Bengal District Records: and the State in Modern India, Cambridge

Impact of Changing Technology on the Burdwan, Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta. University Press.

Division of Labour’ in Nirmala Banerjee (ed), Guha, Ranajit (ed) (1982-97): Subaltern Studies: Metcaffe, A (1987): ‘Manning the Mines:

pp 33-152. Writings on South Asian History and Society, Organising Women Out of Class Struggle’,

Bhattacharyya, Harasankar (1985): Zamindars Various Volumes, Oxford University Press, Australian Feminist Studies, Vol 4, Autumn,

and Patnidars: A Study of Subinfeudation Delhi pp 73-96.

under the Burdwan Raj, Burdwan University Hunter, W W (1872, reprinted in 1973): A Murty, B S and S P Panda (1988): Indian Coal

Press, Burdwan. Statistical Account of Bengal, Vol IV, District Industry and the Coal Miners, Discovery,

Chakrabarty, B (1992): ‘Jawaharlal Nehru and of Bardwan, Bankura and Birbhum, Trubner New Delhi.

Planning: 1938-1941’, Modern Asian Studies, and Co, London, reprinted by DK Publishing Paterson, J C K (1910): Bengal District Gazetteers:

Vol 26, No 2, pp 275-87. House, New Delhi. Burdwan, Bengal Secretariat Book Depot.,

Chakrabarty, Dipesh (1989) Rethinking Working International Labour Organisation (1988): Coal Calcutta.

Class History: Bengal 1890-1940, Oxford Mines Committee, Twelfth Session : Manpower Pathak, Zakia and Rajeswari Sunder Rajan (1992):

University Press, Delhi. Planning, Training and Retraining for Coal ‘Shahbano’ in Judith Butler and Joan Scott

Charlton, Sue Ellen M, Jana Everett and Kathleen Mining in the Light of Technological Changes, (eds), Feminists Theorise the Political,

Staudt (eds) (1989): Women, The State and Report II, International Labour Office, Geneva. Routledge, London.

Development, State University of New York – (1988a): Women Workers: Selected ILO Parpart, Jane L (1995): ‘Post-Modernism, Gender

Press, Albany. Documents, Second Edition, International and Development’ in Jonathan Crush (ed),

Chatterjee, Partha (1993): The Nation and Its Labour Office, Geneva. Power of Development, Routledge, London.

Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial – (1996): International Labour Conventions and Read, Margaret (1931): The Indian Peasant

Histories, Princeton University Press, Recommendations 1919-1951, Vol 1, Uprooted, London.

Princeton, New Jersey. International Labour Office, Geneva. Roy Chaudhury, Rakhi (1996): Gender and Labour

Chaudhuri, M R (1971): The Industrial Landscape – (1997): Sectoral Activities: Mining, International in India : The Kamins of Eastern Coalmines,

of West Bengal: An Economic Geographic Labour Office, Geneva. 1900-1940, Minerva, Calcutta.

Appraisal, Oxford and IBH Publishing, – (1999): Social and Labour Issues in Small Scale Rothermund, Dietmar and D C Wadhwa (eds)

Calcutta. Mines, International Labour Office, Geneva. (1978): Zamindars, Mines and Peasants :

Coal (1999): World Hard Coal Production, 1989- Jhabvala, Renana (1985): ‘From the Mill to the Studies in the History of an Indian Coalfield

1998 (Mt), BP Statistical Review. Streets: A Study of Retrenchment of Women and its Rural Hinterland, Manohar

Dange, S A (1945): Death Pits in Our Land: How From Ahmedabad Textile Mills’, Manushi, Publications, New Delhi.

2,00,000 Indian Miners Live and Work, Asia Vol 26, No 2, pp 2-5. Risley, H H (1891, reprinted in 1998): The Tribes

Publishing House, Bombay. Karlekar, Malavika (1986): ‘Kadambini and and Castes of Bengal, Volumes I and II, Firma

De Haan, Arjan and Samita Sen (1999): A Case Bhadralok: Early Debates Over Women’s KLM, Calcutta.

for Labour History: The Jute Industry in Education in Bengal’, Economic and Political Standing, Hilary (1991): Dependence and

Eastern India, KP Bagchi and Company, Weekly: Review of Women’s Studies 21, pp Autonomy: Women’s Employment and the

Calcutta. WS 25-31. Family in Calcutta, Routledge, London.

Deshpande, S R (1946): Report of an Enquiry into – (1991): Voices From Within: Early Personal Tauli-Corpuz, Victoria (1988): ‘The Globalisation

the Conditions of Labour in the Coal Mining Narratives of Bengali Women, Oxford of Mining and its Impact and Challenges for

Industry in India, Government of India, New University Press, Delhi. Women, Third World Resurgence, No 93,

Delhi. Kumarmangalam, S M (1973): Coal Industry in May 1998.

Dhar, B B and R Thakur (eds) (1995): Mining India – Nationalisation and Tasks Ahead, Venkateswaran, Sandhya (1995): Environment,

Environment, Oxford and IBH, New Delhi. Oxford and IBH Publishing, New Delhi. Development and the Gender Gap, Sage

Eddy, Reverend T M (1854): ‘Women in the Lahiri-Dutt, Kuntala (1996): ‘Occupational Publications, New Delhi.

Economic and Political Weekly November 3, 2001 4221

Вам также может понравиться

- Sumit Sarkar - Tanika Sarkar - Women and Social Reform in Modern India - A Reader Vol 1. 1Документ476 страницSumit Sarkar - Tanika Sarkar - Women and Social Reform in Modern India - A Reader Vol 1. 1mohd amees100% (1)

- Earth and Life Science, Grade 11Документ6 страницEarth and Life Science, Grade 11Gregorio RizaldyОценок пока нет

- (QII-L2) Decorate and Present Pastry ProductsДокумент30 страниц(QII-L2) Decorate and Present Pastry ProductsLD 07100% (1)

- Catalogo Escavadeira EC27CДокумент433 страницыCatalogo Escavadeira EC27CNilton Junior Kern50% (2)

- Kuntala Article For Mining WomenДокумент18 страницKuntala Article For Mining WomenShipShapeОценок пока нет

- International Labor and Working-Class, Inc., Cambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class HistoryДокумент29 страницInternational Labor and Working-Class, Inc., Cambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class HistorysmrithiОценок пока нет

- Modern Bondage: Atyaayma in Post - Abolition MalabarДокумент22 страницыModern Bondage: Atyaayma in Post - Abolition MalabarKT RammohanОценок пока нет

- Jmra 6 3 129 131Документ3 страницыJmra 6 3 129 131Vivek KediaОценок пока нет

- Unit-8 Early Historic Societies 6th Century - 4th Century A.D.Документ8 страницUnit-8 Early Historic Societies 6th Century - 4th Century A.D.Ayush SinghalОценок пока нет

- AhonaДокумент4 страницыAhonaAsif AОценок пока нет

- Unit 28Документ8 страницUnit 28Ti XuОценок пока нет

- Ebhr 18: ReviewsДокумент3 страницыEbhr 18: ReviewsAshwin ThakaliОценок пока нет

- Weaver's MigrationДокумент34 страницыWeaver's MigrationShreya KaleОценок пока нет

- Interpreting Untouchability: The Performance of Caste in Andhra Pradesh, South IndiaДокумент24 страницыInterpreting Untouchability: The Performance of Caste in Andhra Pradesh, South IndiabhasmakarОценок пока нет

- Maria Mies - Dynamics of Sexual Division of Labour and Capital AccumulationДокумент10 страницMaria Mies - Dynamics of Sexual Division of Labour and Capital Accumulationzii08088Оценок пока нет

- Peasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990Документ6 страницPeasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990RajnishОценок пока нет

- Mining and Social Transformation in Africa - DR Deborah BrycesonДокумент16 страницMining and Social Transformation in Africa - DR Deborah BrycesonRepoa TanzaniaОценок пока нет

- Women and Work Contemp S AsiaДокумент20 страницWomen and Work Contemp S AsiaChandan BoseОценок пока нет

- Social Changes PeasantizationДокумент6 страницSocial Changes PeasantizationChetna UttwalОценок пока нет

- A. Akhyat - The of The PeasantryДокумент9 страницA. Akhyat - The of The PeasantryTeukuRezaFadeliОценок пока нет

- Harvard Univ. Agrarian Labor Conference Abstracts - 0Документ11 страницHarvard Univ. Agrarian Labor Conference Abstracts - 0Arthur RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Redressing The Stigma PDFДокумент15 страницRedressing The Stigma PDFKaRan K KHetani100% (1)

- Woman Craft WorkДокумент20 страницWoman Craft WorkShakuntla SangamОценок пока нет

- 27.post Maurayan EconomyДокумент10 страниц27.post Maurayan EconomydbzОценок пока нет

- Social Changes - Peasantization - Profileration of CastesДокумент6 страницSocial Changes - Peasantization - Profileration of CastesSaejal KapoorОценок пока нет

- Aspects of Craft Production in Pre-Modern South Kanara by Dr. Nagendra RaoДокумент22 страницыAspects of Craft Production in Pre-Modern South Kanara by Dr. Nagendra RaoRanbir Singh PhogatОценок пока нет

- CBSE Class 12 Sociology Social Change and Development in India Revision Notes Chapter 1Документ5 страницCBSE Class 12 Sociology Social Change and Development in India Revision Notes Chapter 1Ayesha NadeemОценок пока нет

- Black and White Detailed Floral Illustrations Marketing Presentation PDFДокумент52 страницыBlack and White Detailed Floral Illustrations Marketing Presentation PDFPinaki ChandraОценок пока нет

- 3790159Документ29 страниц3790159Sambuddha GhoshОценок пока нет

- Nair, Dangerous Labour Crime Work and Punishment in Kolar Gold Fields 1890 1946Документ43 страницыNair, Dangerous Labour Crime Work and Punishment in Kolar Gold Fields 1890 1946Suchintan DasОценок пока нет

- Sen Gendered ExclusionДокумент22 страницыSen Gendered ExclusionDavidОценок пока нет

- Unit-8 Ancient, Medieval and ColonialДокумент10 страницUnit-8 Ancient, Medieval and Colonialanuj dhuppadОценок пока нет

- Problems and Welfare of Our Women WorkersДокумент11 страницProblems and Welfare of Our Women WorkersYogi A SОценок пока нет

- The Diversities of Tribal Resistance in Colonial Orissa 1840s1890sДокумент10 страницThe Diversities of Tribal Resistance in Colonial Orissa 1840s1890sShay WaxenОценок пока нет

- Unit 32Документ14 страницUnit 32Jigyasa SinghalОценок пока нет

- Accumulation by Subordination: Migration-Underdevelopment in The Open EconomyДокумент8 страницAccumulation by Subordination: Migration-Underdevelopment in The Open EconomySocial Scientists' AssociationОценок пока нет

- Bengal Zamindari SystemДокумент18 страницBengal Zamindari SystemSoham Banerjee50% (2)

- Pakistan - Women in A Changing SocietyДокумент4 страницыPakistan - Women in A Changing SocietyLucifer 5292Оценок пока нет

- Meena Radha KrishnaДокумент11 страницMeena Radha KrishnaAbhilash MalayilОценок пока нет

- Traditional Embroidery of The Todas and Its Importance: Amutha.BДокумент9 страницTraditional Embroidery of The Todas and Its Importance: Amutha.BJahnvi GuptaОценок пока нет

- Ratnabali Chatterjee - Prostitution in Nineteenth Century Bengal - Construction of Class and GenderДокумент15 страницRatnabali Chatterjee - Prostitution in Nineteenth Century Bengal - Construction of Class and GenderAnkan KaziОценок пока нет

- American Oriental Society Journal of The American Oriental SocietyДокумент12 страницAmerican Oriental Society Journal of The American Oriental SocietyankitОценок пока нет

- Artisans in 18th CenturyДокумент1 страницаArtisans in 18th Centurytanya sainiОценок пока нет

- Patel Displacement OrissaДокумент3 страницыPatel Displacement OrissaTani NgangbamОценок пока нет

- History of Jharkhand MovementДокумент4 страницыHistory of Jharkhand MovementbibinОценок пока нет

- Because They Want Nice ThingsДокумент10 страницBecause They Want Nice ThingstomothyОценок пока нет

- English Literature NotesДокумент3 страницыEnglish Literature NotesMr. Rain ManОценок пока нет

- Bank Matrifocality2008 1Документ27 страницBank Matrifocality2008 1Miguel MucaveleОценок пока нет

- Peasant and Tribal MovementsДокумент17 страницPeasant and Tribal MovementsNeha GautamОценок пока нет

- Final-37-47 Watal CommunityДокумент11 страницFinal-37-47 Watal CommunityHaseeb GulzarОценок пока нет

- HOI Assignment 2Документ7 страницHOI Assignment 2ansamariya15Оценок пока нет

- Book Review CameronДокумент4 страницыBook Review CamerondentsavvyОценок пока нет

- Anti MiningДокумент5 страницAnti Miningguptavaishali564Оценок пока нет

- Dissertation First ChapterДокумент13 страницDissertation First Chapterashly thomasОценок пока нет

- Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Colonial Burma - An Exploratory Study of The Role of Nattukottai Chettiars of Tamil Nadu, 1880-1930Документ30 страницImmigrant Entrepreneurs in Colonial Burma - An Exploratory Study of The Role of Nattukottai Chettiars of Tamil Nadu, 1880-1930mjason1Оценок пока нет

- IJRSML 2018 Vol06 SP Issue 3 56 PDFДокумент4 страницыIJRSML 2018 Vol06 SP Issue 3 56 PDFDipsikha AcharyaОценок пока нет

- Position of Women in MIДокумент4 страницыPosition of Women in MIsmrithiОценок пока нет

- Economic Condition of Women in Ancient India Book TypingДокумент41 страницаEconomic Condition of Women in Ancient India Book TypingRajeshKumarJainОценок пока нет

- Interrogating Indian Nationalism in The Postcolonial Context PDFДокумент12 страницInterrogating Indian Nationalism in The Postcolonial Context PDFsverma6453832Оценок пока нет

- Atul History ProjectДокумент9 страницAtul History ProjectYadav SinghОценок пока нет

- Debate On Indian Feudalis 1Документ5 страницDebate On Indian Feudalis 1Diksha SharmaОценок пока нет

- Joshi 1985Документ30 страницJoshi 1985Om ChadhaОценок пока нет

- Rethinking Resource CurseДокумент8 страницRethinking Resource CurseShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Not A Small JobДокумент24 страницыNot A Small JobShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Book Review of City in ActionДокумент30 страницKLD Book Review of City in ActionShipShapeОценок пока нет

- NRF ViewpointДокумент5 страницNRF ViewpointShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Moving Pictures SpreadsДокумент35 страницMoving Pictures SpreadsShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Self Help Groups and Social CapitalДокумент11 страницSelf Help Groups and Social CapitalShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Coal Sector Loans & Lessons From JharkhandДокумент7 страницKLD Coal Sector Loans & Lessons From JharkhandShipShapeОценок пока нет

- EPW Illegal Dec 07Документ10 страницEPW Illegal Dec 07ShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Kosi Flood 2008Документ3 страницыKosi Flood 2008ShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Deb, Tiwari & Lahiri-Dutt On ASMДокумент17 страницDeb, Tiwari & Lahiri-Dutt On ASMShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Zillur - Lahiri-Dutt Paper On BangladeshДокумент14 страницZillur - Lahiri-Dutt Paper On BangladeshShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Women, Water and RightsДокумент24 страницыKLD Women, Water and RightsShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD State, Market & The Crisis in Raniganj CoalbeltДокумент5 страницKLD State, Market & The Crisis in Raniganj CoalbeltShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Fluid Bonds IntroductionДокумент22 страницыKLD Fluid Bonds IntroductionShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD-KR Feminist Review PapertДокумент31 страницаKLD-KR Feminist Review PapertShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD South Asian SurveyДокумент28 страницKLD South Asian SurveyShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Negotiating Water MGMNT in DVCДокумент23 страницыKLD Negotiating Water MGMNT in DVCShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Char Security South AsiaДокумент24 страницыChar Security South AsiaShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Social ChangeДокумент14 страницKLD Social ChangeShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD GeographyДокумент9 страницKLD GeographyShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Coal Sector Loans & Lessons From JharkhandДокумент7 страницKLD Coal Sector Loans & Lessons From JharkhandShipShapeОценок пока нет

- KLD Community Engagement in MiningДокумент13 страницKLD Community Engagement in MiningShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Imagining RiversДокумент6 страницImagining RiversShipShapeОценок пока нет

- A Day in BorneoДокумент10 страницA Day in BorneoShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Gendering The Field CoverДокумент1 страницаGendering The Field CoverShipShapeОценок пока нет

- A Day in BorneoДокумент10 страницA Day in BorneoShipShapeОценок пока нет

- Chapter 08 MGT 202 Good GovernanceДокумент22 страницыChapter 08 MGT 202 Good GovernanceTHRISHIA ANN SOLIVAОценок пока нет

- ISSA2013Ed CabinStores v100 Часть10Документ2 страницыISSA2013Ed CabinStores v100 Часть10AlexanderОценок пока нет

- 2 Calculation ProblemsДокумент4 страницы2 Calculation ProblemsFathia IbrahimОценок пока нет

- Previous Papers GPSC Veterinary Officer AHI Advt. No. 33 2016 17 Date of Preliminary Test 08 01 2017 Subject Concerned Subject Que 101 To 300 Provisional Key PDFДокумент18 страницPrevious Papers GPSC Veterinary Officer AHI Advt. No. 33 2016 17 Date of Preliminary Test 08 01 2017 Subject Concerned Subject Que 101 To 300 Provisional Key PDFDrRameem Bloch100% (1)

- Adsorption ExperimentДокумент5 страницAdsorption ExperimentNauman KhalidОценок пока нет

- LP MAPEH 10 1st Quarter Printing Final.Документ29 страницLP MAPEH 10 1st Quarter Printing Final.tatineeesamonteОценок пока нет

- Under Suitable Conditions, Butane, C: © OCR 2022. You May Photocopy ThisДокумент13 страницUnder Suitable Conditions, Butane, C: © OCR 2022. You May Photocopy ThisMahmud RahmanОценок пока нет

- Oral Com Reviewer 1ST QuarterДокумент10 страницOral Com Reviewer 1ST QuarterRaian PaderesuОценок пока нет

- The Chassis OC 500 LE: Technical InformationДокумент12 страницThe Chassis OC 500 LE: Technical InformationAbdelhak Ezzahrioui100% (1)

- List of Bird Sanctuaries in India (State-Wise)Документ6 страницList of Bird Sanctuaries in India (State-Wise)VISHRUTH.S. GOWDAОценок пока нет

- Model DPR & Application Form For Integrated RAS PDFДокумент17 страницModel DPR & Application Form For Integrated RAS PDFAnbu BalaОценок пока нет

- 2022 NEDA Annual Report Pre PubДокумент68 страниц2022 NEDA Annual Report Pre PubfrancessantiagoОценок пока нет

- PPT-QC AcДокумент34 страницыPPT-QC AcAmlan Chakrabarti Calcutta UniversityОценок пока нет

- Reviewer in EntrepreneurshipДокумент6 страницReviewer in EntrepreneurshipRachelle Anne SaldeОценок пока нет

- ADMT Guide: Migrating and Restructuring Active Directory DomainsДокумент263 страницыADMT Guide: Migrating and Restructuring Active Directory DomainshtoomaweОценок пока нет

- New Text DocumentДокумент13 страницNew Text DocumentJitendra Karn RajputОценок пока нет

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesДокумент1 страницаDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesKlaribelle VillaceranОценок пока нет

- Investing in Granada's Property Market - Gaspar LinoДокумент1 страницаInvesting in Granada's Property Market - Gaspar LinoGaspar LinoОценок пока нет

- History of Old English GrammarДокумент9 страницHistory of Old English GrammarAla CzerwinskaОценок пока нет

- Rwamagana s5 Mathematics CoreДокумент4 страницыRwamagana s5 Mathematics Coreevariste.ndungutse1493Оценок пока нет