Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cable 167: UN High Commissioner On Human Rights Report On Colombia

Загружено:

Andres0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

30 просмотров8 страницThis is a 2004 US embassy report summarizing the findings of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights (UNHCHR), who was investigating Colombian compliance with previous recommendations of the UNHCHR.

Оригинальное название

Cable 167: UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Report on Colombia

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документThis is a 2004 US embassy report summarizing the findings of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights (UNHCHR), who was investigating Colombian compliance with previous recommendations of the UNHCHR.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

30 просмотров8 страницCable 167: UN High Commissioner On Human Rights Report On Colombia

Загружено:

AndresThis is a 2004 US embassy report summarizing the findings of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights (UNHCHR), who was investigating Colombian compliance with previous recommendations of the UNHCHR.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 8

Wikileaks Note: The full text of this cable is not

available.

ID: 14143

Date: 2/20/2004 17:20

RefID: 04BOGOTA1748

Origin: Embassy Bogota

C O N F I D E N T I A L SECTION 01 OF 03 BOGOTA

001748

SUBJECT: UNHCHR REPORT ON COLOMBIA

Classified By: Charge Milton Drucker for reasons

1.5 (b&d)

¶1. (C) Summary: The Office of the UN High

Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) in Colombia

is finalizing its report for Geneva on the GOC's

compliance with its 27 human rights

recommendations. The report is likely to

criticize the GOC for slow and uneven

implementation of the recommendations and its

refusal to implement two, or possibly three,

recommendations. Nevertheless, it will recognize

that the GOC fulfilled one recommendation,

accomplished substantial progress in another, and

achieved varying progress in half a dozen others.

A group of foreign missions seeking to help

the GOC fulfill the recommendations believes that

UNHCHR's compliance assessment may give the GOC

insufficient credit on several recommendations, and

has encouraged the GOC to draft its own assessment

for distribution in Geneva. End Summary.

¶2. (C) The Colombia office of the UN High

Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), under

director Michael Fruhling, is putting the finishing

touches on its evaluation of the GOC's

compliance with 27 human rights recommendations

made in the office's 2002 human rights report and

issued in March 2003. The office will make public

in early March its official report on the

recommendations, prior to the UN Human Rights

Commission's annual meeting in Geneva. In meetings

with foreign embassies, Fruhling has criticized the

GOC for waiting too long to engage seriously on

implementing the recommendations and for its uneven

commitment to them. The Ministry of Defense and

Office of the Prosecutor General (“Fiscalia”) have

been particular laggards, he maintains. Of the 27

recommendations, 20 are directed at the executive

branch, four at the independent Fiscalia, and three

at illegal armed groups. According to Fruhling,

the executive branch has fulfilled one

recommendation, accomplished substantial progress

in a second, achieved varying progress in half a

dozen others, and rejected two or three.

¶3. (C) Fruhling intends to propose in Geneva that

the UNHCHR be given a mandate to develop a second

set of recommendations, drawn from the current 27,

that would guide his office's work for the next 12

months. Colombian Vice president Francisco Santos,

who has the lead on human rights within the GOC,

would prefer to discard the current set of

recommendations and replace them with more general

goals that would allow greater operational

flexibility. According to Santos, the current

recommendations place too much emphasis

on taking bureaucratic steps and not enough on

addressing fundamental human rights problems.

¶4. (C) The European Union and some individual

European countries have emphasized the need for the

GOC to comply fully with the 27 recommendations, in

some cases putting such a premium on compliance

with the recommendations that they overlook real

improvements achieved by the Uribe administration

in reducing violence and human rights crimes

in Colombia. Many Colombian human rights NGOs

critical of Uribe and his Government have

vociferously advanced the view that the GOC's

uneven compliance with the recommendations

demonstrates a lack of commitment to human rights.

¶5. (C) To assist the GOC with the implementation

of the recommendations, seven embassies accredited

to Colombia -- Brazil, the Netherlands, Spain,

Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the U.S. -- have

formed an informal working group known locally as

the G-7. Over the last two months, G-7

representatives have met with Fruhling and Santos,

both separately and together. Predictably, these

meetings have highlighted differences between the

GOC's and UNHCHR's assessments of the Government's

compliance with several of the recommendations.

¶6. (C) Although Fruhling has declined to share an

advanced draft of his report to Geneva with G-7

ambassadors, he provided the following oral

snapshot to them on February 13:

--The GOC has fulfilled the recommendation on

anti-personnel mines (13).

--The GOC has achieved significant progress in

improving the effectiveness of the Early Warning

System (1).

--The GOC has made some, but still insufficient,

progress in: protecting human rights defenders

(2); increasing protection for communities at

risk (4); implementing human rights training at

the Ministry of Defense (8); and improving the

public security forces' adherence to

international humanitarian law (12). (Note: The

Embassy believes the UNHCHR report will give

insufficient weight to the Government's

extension of state presence throughout the

country and success at reducing key indicators

of violence, including against human rights

defenders and communities at risk. Virtually

all the G-7 ambassadors criticized Fruhling for

not giving the GOC more credit for the Ministry

of Defense's human rights training. Public

security personnel continue to commit only a

small fraction of human rights violations. End

note.)

--The GOC has not assigned personnel from the

Inspector General's ("Procuraduria") and

Ombudsman's ("Defensoria") offices to all

conflictive areas (5), although international

funding had helped the GOC assign such personnel

to many remote and problematic regions. (Note:

Fruhling gives the GOC insufficient credit for

having representatives of the Ombudsman's office

in all 33 of Colombia's departments. End note.)

--The Vice President has established a Special

Committee (20) to advance investigations and

prosecutions in select human rights cases, but

progress in closing cases has been too slow.

(Note: The GOC had significantly advanced six of

the one-hundred cases by the end of 2003, and

hopes to have advanced another 15 cases by the

end of February. End note.)

--Although the GOC is negotiating with several

paramilitary organizations, neither the FARC nor

the ELN are prepared to enter into dialogue with

the Government. It is essential that the GOC's

negotiations with illegal armed groups be

guided by principles of truth, justice, and

reparations (14).

--The Inspector General ("Procuraduria") has not

taken disciplinary actions against all state

employees who in any way jeopardized the work of

human rights defenders (6). In this regard,

some public pronouncements from senior GOC

officials have been unhelpful.

--Although President Uribe has been clear on the

need to sever the public security forces' links

with paramilitaries (21), more actions need to

be taken

--The GOC has begun preparing a national plan of

action on human rights (23), but has not given

local governments and key sectors of society

(read human rights NGOs) necessary input.

--There have been positive discussions with the

Ministry of Education on incorporating human

rights education in the national curriculum (24)

and providing human rights training to judicial

entities (25), but little concrete progress has

been achieved.

--Although the Vice President's Office has

worked productively with UNHCHR, the GOC as a

whole has not taken sufficient advantage of the

office's human rights expertise (26 and 27).

--The GOC faces a major challenge in developing

policies to narrow the economic inequality gap

in Colombia (22).

--The Ministry of Defense is resisting the

requirement to suspend from duty public security

force personnel implicated in serious human

rights violations (19) by relying on what

Fruhling believes is an erroneous reading of

relevant legal

codes.

--The GOC made it clear, at the July 2003 London

Conference and subsequently, its disagreement

with recommendations calling for it not to adopt

anti-terrorism legislation giving the military

arrest powers (15) and for the independent

Inspector General's Office ("Procuraduria") to

inspect military intelligence files on human

rights defenders and publish the results (7).

Fruhling maintains that the GOC agreed to these

recommendations in March 2003 at Geneva, and

is therefore bound. (Note: The Colombian

Congress approved an anti-terrorism statute in

December and will consider implementing

legislation next session. The UNHCHR is

exploring with the Defense Ministry a possible

compromise on the review of military

intelligence files. End note.)

--The Prosecutor General's Office ("Fiscalia")

only signed in November an agreement to work

with UNHCHR, so no concrete results have been

achieved on recommendations 3, 16, 17, and 18.

¶7. (C) During the past week, however, a majority

of G-7 representatives concluded at meeting with

Fruhling that UNHCHR gives the GOC insufficient

credit for compliance with some of the

recommendations and that in others it demands

that the GOC go beyond the language of the

recommendations. In particular, the Dutch and

Swedish Ambassadors, who are among the most

conspicuous champions of human rights within

the local diplomatic community, openly questioned

whether Fruhling has been excessively demanding in

his assessments of GOC compliance.

¶8. (C) On February 18, Vice President Santos met

with G-7 ambassadors and excoriated the draft

report Fruhling had shown him. He said that the

report was highly inaccurate in key sections; the

GOC could accept damning assessments, but

they should at least be accurate. Santos claimed

that he "did not know how to show the draft report

to President Uribe." He asked for advice.

¶9. (C) The Brazilian ambassador urged Santos to

produce a GOC drafted human rights report, noting

progress where warranted but admitting shortfalls,

for the UN Human Rights Committee meeting in

Geneva. She was supported by the other G-7

ambassadors present. The G-7 group then met at the

Swiss embassy without Santos and came to the same

conclusion. No one had much confidence, including

the Swedish ambassador, that Fruhling would modify

his report before sending it as a draft to Geneva.

Subsequently, the Swedish ambassador privately

indicated to us that he is considering recommending

that the GOS question the draft report's

assessments in Geneva -- which would be a

surprising development, given that Fruhling is a

former Swedish diplomat.

¶10. (C) Comment: The more critical stance of the

G-7 ambassadors regarding certain aspects of the

UNHCHR Colombia office's report may not translate

into a willingness to criticize it in Geneva. It

has, however, put Fruhling on notice that he runs

such a risk. End Comment.

Butenis

(Edited and reformatted by Andres for ease of

reading.)

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Cable 1045: Drug Cartels and Palm Oil Companies Target Catholic Priests in Northern ColombiaДокумент5 страницCable 1045: Drug Cartels and Palm Oil Companies Target Catholic Priests in Northern ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1039: Military Personnel Tied To Drug Trafficking Organizations in ColombiaДокумент4 страницыCable 1039: Military Personnel Tied To Drug Trafficking Organizations in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1044: Colombian Army Colonel Arrested For Involvement in "False Positive" Extrajudicial KillingsДокумент2 страницыCable 1044: Colombian Army Colonel Arrested For Involvement in "False Positive" Extrajudicial KillingsAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1043: Arrest of Mayor Reveals Ties Between Chiquita and Right Wing Paramilitaries in ColombiaДокумент3 страницыCable 1043: Arrest of Mayor Reveals Ties Between Chiquita and Right Wing Paramilitaries in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1040: 2008 Data On Violence Against Labor Activists in ColombiaДокумент2 страницыCable 1040: 2008 Data On Violence Against Labor Activists in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1038: Fallout Continues in Colombian "Parapolitics" ScandalДокумент5 страницCable 1038: Fallout Continues in Colombian "Parapolitics" ScandalAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1042: Paramilitary Drug Cartels Wage War in ColombiaДокумент5 страницCable 1042: Paramilitary Drug Cartels Wage War in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1041: Colombian President Denies Involvement in 1997 Paramiltary MassacreДокумент2 страницыCable 1041: Colombian President Denies Involvement in 1997 Paramiltary MassacreAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1034: Colombian Supreme Court Reopens Investigation Into Colombian Army Involvement in 1987 MassacreДокумент3 страницыCable 1034: Colombian Supreme Court Reopens Investigation Into Colombian Army Involvement in 1987 MassacreAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1035: New Criminal Groups Fill Void Left by Demobilized Paramiltaries in ColombiaДокумент5 страницCable 1035: New Criminal Groups Fill Void Left by Demobilized Paramiltaries in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1036: "Aguilas Negras" and The Reemergence of Paramilitary Violence in ColombiaДокумент3 страницыCable 1036: "Aguilas Negras" and The Reemergence of Paramilitary Violence in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1037: Colombian Army Linked To 2005 San Jose de Apartado MassacreДокумент3 страницыCable 1037: Colombian Army Linked To 2005 San Jose de Apartado MassacreAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1032: 2008 US Embassy Report On Violence Against Labor Activists in ColombiaДокумент3 страницыCable 1032: 2008 US Embassy Report On Violence Against Labor Activists in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1033: US Meets With Human Rights Groups To Discuss Extrajudicial Killings in ColombiaДокумент4 страницыCable 1033: US Meets With Human Rights Groups To Discuss Extrajudicial Killings in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1029: Land Seizures by Palm Oil Companies Destabilize Afro-Colombian Communities in Northern ColombiaДокумент6 страницCable 1029: Land Seizures by Palm Oil Companies Destabilize Afro-Colombian Communities in Northern ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1028: 2008 US Embassy Report On Proposed "Cooperative Security Location" in ColombiaДокумент2 страницыCable 1028: 2008 US Embassy Report On Proposed "Cooperative Security Location" in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Report 6: Iraqi Commando Unit Tied To 2005 Extrajudicial Killings in BaghdadДокумент1 страницаReport 6: Iraqi Commando Unit Tied To 2005 Extrajudicial Killings in BaghdadAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1031: Controversy Over 2008 Targeted Killing of FARC Commander in EcuadorДокумент5 страницCable 1031: Controversy Over 2008 Targeted Killing of FARC Commander in EcuadorAndresОценок пока нет

- Report 7: Iraqi "Volcano Brigade" Accused of Responsibility For 2005 Sectarian Massacre in BaghdadДокумент1 страницаReport 7: Iraqi "Volcano Brigade" Accused of Responsibility For 2005 Sectarian Massacre in BaghdadAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1030: Colombian Army Personnel Found Guilty in Massacre of US-Trained Anti-Drug UnitДокумент3 страницыCable 1030: Colombian Army Personnel Found Guilty in Massacre of US-Trained Anti-Drug UnitAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1024: 2007 US Embassy Report On Steps Taken To Address Extrajudicial Killings in ColombiaДокумент7 страницCable 1024: 2007 US Embassy Report On Steps Taken To Address Extrajudicial Killings in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1027: Colombia Captures Rebel Commander in US-Supported OperationДокумент4 страницыCable 1027: Colombia Captures Rebel Commander in US-Supported OperationAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1026: Investigations Continue in Colombian "Parapolitical Scandal"Документ5 страницCable 1026: Investigations Continue in Colombian "Parapolitical Scandal"AndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1023: Colombian Prosecutor General Faces Backlog of Extrajudicial Killing InvestigationsДокумент4 страницыCable 1023: Colombian Prosecutor General Faces Backlog of Extrajudicial Killing InvestigationsAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1020: US-Supported Targeted Killing Operations in ColombiaДокумент6 страницCable 1020: US-Supported Targeted Killing Operations in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1025: Colombian Army Officers Face Justice For 1997 Mapiripan MassacreДокумент2 страницыCable 1025: Colombian Army Officers Face Justice For 1997 Mapiripan MassacreAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1021: Colombian Army Lured Farmworkers Into "False Positive" Murder OperationДокумент4 страницыCable 1021: Colombian Army Lured Farmworkers Into "False Positive" Murder OperationAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1022: US Embassy Seeks To Restore Aid To Colombian Air Force Unit Involved in 1998 Bombing of Village in Northeastern ColombiaДокумент2 страницыCable 1022: US Embassy Seeks To Restore Aid To Colombian Air Force Unit Involved in 1998 Bombing of Village in Northeastern ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1019: Oil and Human Rights in ColombiaДокумент6 страницCable 1019: Oil and Human Rights in ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Cable 1018: The Influence of Paramilitaries On Local Elections in Northern ColombiaДокумент6 страницCable 1018: The Influence of Paramilitaries On Local Elections in Northern ColombiaAndresОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Scott Gessler Appeal of Ethics Commission Sanctions - Opening BriefДокумент56 страницScott Gessler Appeal of Ethics Commission Sanctions - Opening BriefColorado Ethics WatchОценок пока нет

- The Forrester Wave PDFДокумент15 страницThe Forrester Wave PDFManish KumarОценок пока нет

- Presentation 2Документ35 страницPresentation 2Ma. Elene MagdaraogОценок пока нет

- Setting Up Ansys Discovery and SpaceClaimДокумент2 страницыSetting Up Ansys Discovery and SpaceClaimLeopoldo Rojas RochaОценок пока нет

- 0607 WillisДокумент360 страниц0607 WillisMelissa Faria Santos100% (1)

- Fraud Detection and Deterrence in Workers' CompensationДокумент46 страницFraud Detection and Deterrence in Workers' CompensationTanya ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- Document 5Документ6 страницDocument 5Collins MainaОценок пока нет

- NISM Series IX Merchant Banking Workbook February 2019 PDFДокумент211 страницNISM Series IX Merchant Banking Workbook February 2019 PDFBiswajit SarmaОценок пока нет

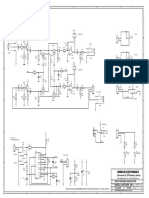

- Nobels Ab1 SwitcherДокумент1 страницаNobels Ab1 SwitcherJosé FranciscoОценок пока нет

- (John J. Miletich) Homicide Investigation An Intr PDFДокумент314 страниц(John J. Miletich) Homicide Investigation An Intr PDFCarl Radle100% (1)

- Avengers - EndgameДокумент3 страницыAvengers - EndgameAjayОценок пока нет

- SAP Project System - A Ready Reference (Part 1) - SAP BlogsДокумент17 страницSAP Project System - A Ready Reference (Part 1) - SAP BlogsSUNIL palОценок пока нет

- Sample Balance SheetДокумент22 страницыSample Balance SheetMuhammad MohsinОценок пока нет

- Filamer Christian Institute V IACДокумент6 страницFilamer Christian Institute V IACHenson MontalvoОценок пока нет

- MSF Tire and Rubber V CA (Innocent Bystander Rule-Labor LawДокумент4 страницыMSF Tire and Rubber V CA (Innocent Bystander Rule-Labor Lawrina110383Оценок пока нет

- Two-Nation TheoryДокумент6 страницTwo-Nation TheoryAleeha IlyasОценок пока нет

- Final ReviewДокумент14 страницFinal ReviewBhavya JainОценок пока нет

- List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB-2019Документ189 страницList of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB-2019Manish Bhardwaj100% (1)

- CHAPTER 12 Partnerships Basic Considerations and FormationsДокумент9 страницCHAPTER 12 Partnerships Basic Considerations and FormationsGabrielle Joshebed AbaricoОценок пока нет

- Reform in Justice System of PakistanДокумент5 страницReform in Justice System of PakistanInstitute of Policy Studies100% (1)

- IOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18Документ5 страницIOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18MiscellaneousОценок пока нет

- Sia vs. PeopleДокумент26 страницSia vs. PeopleoliveОценок пока нет

- ACTBFAR Unit 2 Partnership Part 3 Partnership Operations Study GuideДокумент3 страницыACTBFAR Unit 2 Partnership Part 3 Partnership Operations Study GuideMatthew Jalem PanaguitonОценок пока нет

- Blankcontract of LeaseДокумент4 страницыBlankcontract of LeaseJennyAuroОценок пока нет

- Research - Procedure - Law of The Case DoctrineДокумент11 страницResearch - Procedure - Law of The Case DoctrineJunnieson BonielОценок пока нет

- Nampicuan, Nueva EcijaДокумент2 страницыNampicuan, Nueva EcijaSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Co-Ownership Ong Tan v. Rodriguez GR 230404 January 31, 2018 1 Division: Tijam, JДокумент2 страницыCo-Ownership Ong Tan v. Rodriguez GR 230404 January 31, 2018 1 Division: Tijam, JApril John LatorzaОценок пока нет

- Cruz v. IAC DigestДокумент1 страницаCruz v. IAC DigestFrancis GuinooОценок пока нет

- JAbraManual bt2020Документ15 страницJAbraManual bt2020HuwОценок пока нет

- Stress and StrainДокумент2 страницыStress and StrainbabeОценок пока нет