Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Adoption of TQM

Загружено:

d.balajiИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Adoption of TQM

Загружено:

d.balajiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Adoption of TQM

The change plan would include tactics designed to move the relevant forces.

It is also important to note and validate any points of resistance which are, in fact, legitimate, such as the

limited amount of staff time available for TQM meetings. Klein (cited in Bennis, Benne, & Chin, 1985)

encouraged change agents to validate the role of the "defender" of the status quo and respond to

legitimate concerns raised. This will allow appropriate adaptations of the TQM process to account for

unique organizational circumstances. Sell TQM based on the organization's real needs, note legitimate

risks and negatives, and allow improvements in your own procedures. This should enhance your

credibility and show your openness to critically looking at the process.

Another way to address resistance is to get all employees on the same side, in alignment towards the

same goal. Leadership is the mechanism for this, and specific models known as transformational or

visionary leadership (Bennis & Nanus, 1985) are most effective. Research on change implementation

(Nutt, cited in Robey, 1991) has identified four methods. The first, "intervention," involves a key executive

justifying the need for change, monitoring the process, defining acceptable performance, and

demonstrating how improvements can be made. This was found to be more successful than

"participation," in which representatives of different interest groups determine the features of the change.

Participation was found to be more successful than "persuasion" (experts attempting to sell changes they

have devised) or "edict," the least successful. Transformational or visionary leadership, the approach

suggested here, is an example of the intervention approach. This would involve a leader articulating a

compelling vision of an ideal organization and how TQM would help the vision be actualized. These

principles will be discussed in more detail in a later section, as a framework for the change strategy.

A powerful way to decrease resistance to change is to increase the participation of employees in making

decisions about various aspects of the process. There are actually two rationales for employee

participation (Packard, 1989). The more common reason is to increase employee commitment to the

resultant outcomes, as they will feel a greater stake or sense of ownership in what is decided. A second

rationale is that employees have a great deal of knowledge and skill relevant to the issue at hand (in this

case, increasing quality, identifying problems, and improving work processes), and their input should lead

to higher quality decisions. A manager should consider any decision area as a possibility for employee

participation, with the understanding that participation is not always appropriate (Vroom and Yetton,

1973). Employees or their representatives may be involved in decision areas ranging from the scope and

overall approach of the TQM process to teams engaging in quality analysis and suggestions for

improvements. They may also be involved in ancillary areas such as redesign of the organization's

structure, information system, or reward system. Involvement of formal employee groups such as unions

is a special consideration which may also greatly aid TQM implementation.

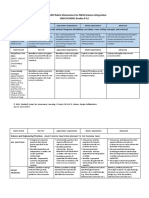

A change agent should understand that, overall, change will occur when three factors (dissatisfaction with

the status quo, desirability of the proposed change, the practicality of the change) added together are

greater than the "cost" of changing (time spent in learning, adapting new roles and procedures, etc.)

(Beckhard and Harris, 1987). This is represented in the formula in Exhibit II. Any key group or individual

will need a level of dissatisfaction with the status quo, must see a desired improved state, and must

believe that the change will have minimal disruption. In other words, the change (TQM) must be seen as

responding to real problems and worth the effort or cost in getting there. Conditions favoring change may

be created by modifying these variables. The change agent may try to demonstrate how bad things are,

or amplify others' feelings of dissatisfaction; and then present a picture of how TQM could solve current

problems. The final step of modifying the equation is to convince people that the change process, while it

will take time and effort, will not be prohibitively onerous. The organization as a whole and each person

will be judging the prospect of TQM from this perspective. A variation of this is the WIIFM principle:

"What's in it for me?" To embrace TQM, individuals must be shown how it will be worth it for them.

Dr. Fathi El-Nadi

Subscribe to Dr. Fathi's articles

(Visit Dr. Fathi's Website) Certified Crosby College TQM Instructor; Management & HR Development Senior Consultant to a number of

Egyptian & Arab enterprises across the Middle East. - Rated by The Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM) as Senior HR

Professional due to his significant contributions to prominent Multinationals in the US, The Gulf, and Egypt. - Had held senior Management,

HR, and Training positions in SOM, Johnson Wax, General Motors, and Bristol Myers Squibb. - Currently teaching Management, HR,

Strategic Management, and OB at a member of prominent private universities in Egypt. - Management & HR Development consultant to

USAID, CIDA, DANIDA & IFC on development projects in Egypt. - Professor, Strategic Management & HR Development (The Arab Academy

for Science & Technology / AUC) - Consultant & Member, The National Committee for Faculty & Leadership Development Project (FLDP), a

7 year World Bank Funded project to enhance the quality of Higher Education in Egypt. - Consultant to a number of Egyptian State

universities on Strategic Planning & Quality Improvement projects.

Dr. Fathi El-Nadi is a Platinum author on EvanCarmichael.com

Вам также может понравиться

- Quality Management (TQM)Документ4 страницыQuality Management (TQM)Mohd Nasri MuaratОценок пока нет

- Managing the Transition to TQM in 4 StepsДокумент1 страницаManaging the Transition to TQM in 4 StepsMay AliceОценок пока нет

- Role of Comms & Employee Engagement in Effective Change ManagementДокумент8 страницRole of Comms & Employee Engagement in Effective Change ManagementSavithri NandadasaОценок пока нет

- Demystifying The Legend of Resistance To ChangeДокумент8 страницDemystifying The Legend of Resistance To ChangeNader Ale EbrahimОценок пока нет

- TQM and Organizational Change and DevelopmentДокумент15 страницTQM and Organizational Change and DevelopmentKhairunisa Hida IsmailОценок пока нет

- SID#: 1031425/1 Module: Organizational Behavior: Edition P 662)Документ10 страницSID#: 1031425/1 Module: Organizational Behavior: Edition P 662)Karen KaveriОценок пока нет

- The Development Validation and Practical Application of An Employee Agility and Resilience Measure To Facilitate Organizational ChangeДокумент21 страницаThe Development Validation and Practical Application of An Employee Agility and Resilience Measure To Facilitate Organizational ChangemaginvbОценок пока нет

- OD Change at Fox AirlineДокумент7 страницOD Change at Fox AirlineTalhaFarrukhОценок пока нет

- The Role of Leadership in Conducting Successful Change ManagementДокумент7 страницThe Role of Leadership in Conducting Successful Change Managementwaleed AfzaalОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis of Change Management ModelsДокумент13 страницComparative Analysis of Change Management ModelsJesus Antonio Ordoñez CampoОценок пока нет

- Change Management Process Research PaperДокумент8 страницChange Management Process Research Papervehysad1s1w3100% (1)

- A Framework For Managing Change in OrganizationsДокумент13 страницA Framework For Managing Change in OrganizationsAbdulrahmanОценок пока нет

- Managing Change and Organizational DevelopmentДокумент16 страницManaging Change and Organizational DevelopmentMuhammad ImranОценок пока нет

- Project 111Документ25 страницProject 111Dhanashri TawareОценок пока нет

- MG302 Group Assignment (A5) S1 2021Документ13 страницMG302 Group Assignment (A5) S1 2021Regional SwamyОценок пока нет

- Change Management PaperДокумент16 страницChange Management PaperEko SuwardiyantoОценок пока нет

- 2.2 MticДокумент28 страниц2.2 MtichardikОценок пока нет

- Human Resource Management 3rd Edition Hartel Solutions ManualДокумент12 страницHuman Resource Management 3rd Edition Hartel Solutions ManualLaurenBatesardsj100% (13)

- Orginizational Change Management PDFДокумент9 страницOrginizational Change Management PDFLillian KahiuОценок пока нет

- Senai AirportkjkjdsfjДокумент19 страницSenai AirportkjkjdsfjAbram TariganОценок пока нет

- Research 2 OdДокумент20 страницResearch 2 OdPlik plikОценок пока нет

- BHR 331assignment Organisatinal Development 201800617Документ8 страницBHR 331assignment Organisatinal Development 201800617Parks WillizeОценок пока нет

- Organizational Change Case Study of GeneДокумент5 страницOrganizational Change Case Study of GeneBrinda anthatiОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4Документ12 страницChapter 4Ebsa AdemeОценок пока нет

- Organisation Change and DevelopmentДокумент5 страницOrganisation Change and DevelopmentPulkit Saini0% (1)

- History: Individuals Teams OrganisationsДокумент6 страницHistory: Individuals Teams OrganisationsNavalmeet Singh SandhuОценок пока нет

- What Is Organizational Development QUE 4Документ7 страницWhat Is Organizational Development QUE 4Chishale FridayОценок пока нет

- Change Management Asignment by Arslan TariqДокумент9 страницChange Management Asignment by Arslan TariqSunny AabaОценок пока нет

- Managing Change: The Process and Impact on PeopleОт EverandManaging Change: The Process and Impact on PeopleРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- ORG ORG ORG ORG Organiza Aniza Aniza Aniza Anizatio TIO TIO TIO Tion N N N Nal Renew Al Renew Al Renew Al Renew Al Renewal AL AL AL ALДокумент12 страницORG ORG ORG ORG Organiza Aniza Aniza Aniza Anizatio TIO TIO TIO Tion N N N Nal Renew Al Renew Al Renew Al Renew Al Renewal AL AL AL ALbutterfly colorfulОценок пока нет

- Managing in An Environment of Continuous ChangeДокумент8 страницManaging in An Environment of Continuous ChangeMohammad Raihanul HasanОценок пока нет

- Unity University MBA Managing Change and Innovation AssignmentTITLE Factors Influencing Organizational Change at Unity UniversityДокумент10 страницUnity University MBA Managing Change and Innovation AssignmentTITLE Factors Influencing Organizational Change at Unity Universityአረጋዊ ሐይለማርያምОценок пока нет

- Change Management in Organizations: Yenkong Jacqueline Kisob, MBAДокумент11 страницChange Management in Organizations: Yenkong Jacqueline Kisob, MBAaijbmОценок пока нет

- The_ethics_of_empowermentДокумент10 страницThe_ethics_of_empowermentmghaseghОценок пока нет

- Assignment TwoДокумент16 страницAssignment TwoRiyaad MandisaОценок пока нет

- Drm11. Management Process & BehaviourДокумент14 страницDrm11. Management Process & BehaviourThiyaga RajanОценок пока нет

- Effective Change InterventionsДокумент21 страницаEffective Change Interventionsmizelly100% (1)

- Change Management: A Process for Managing Organizational TransitionДокумент5 страницChange Management: A Process for Managing Organizational TransitionJihen NasrОценок пока нет

- Change Management For Your OrganisationДокумент5 страницChange Management For Your OrganisationJK100% (1)

- Change ManagementДокумент4 страницыChange ManagementMelai NudosОценок пока нет

- PADM12040Документ8 страницPADM12040robert muzvimweОценок пока нет

- Leading ChangeДокумент93 страницыLeading ChangeChaudhary Ekansh PatelОценок пока нет

- Change ManagementДокумент28 страницChange ManagementAbhijit DileepОценок пока нет

- Managing Human Resources: Case Study - HRD InterventionДокумент6 страницManaging Human Resources: Case Study - HRD InterventionAditi RathiОценок пока нет

- AM - M P C: ETA Odel OF Lanned HangeДокумент9 страницAM - M P C: ETA Odel OF Lanned HangeCyn SyjucoОценок пока нет

- OD Interventions At Chemcorp Improve Public Sector CorpДокумент5 страницOD Interventions At Chemcorp Improve Public Sector CorpsushmitadeepОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9-250608 043528Документ16 страницChapter 9-250608 043528GabrielОценок пока нет

- Organization Development: Growth Focus: Session 6: TSHUMRES Ateneo Graduate School of BusinessДокумент36 страницOrganization Development: Growth Focus: Session 6: TSHUMRES Ateneo Graduate School of BusinessApril OcampoОценок пока нет

- 5049 Harrison Chapter 1Документ26 страниц5049 Harrison Chapter 1Sabu VincentОценок пока нет

- Chapter Four 4. Types of Change 4.1. Planned Versus Unplanned ChangeДокумент8 страницChapter Four 4. Types of Change 4.1. Planned Versus Unplanned ChangeMelkamu TemesgenОценок пока нет

- 1Документ54 страницы1Girma BelateОценок пока нет

- Term Paper On Change ManagementДокумент4 страницыTerm Paper On Change Managementafdtzfutn100% (1)

- What Is Organizational Development?Документ3 страницыWhat Is Organizational Development?Yusra Jamil0% (1)

- OrganizationalDevelopment ReportДокумент4 страницыOrganizationalDevelopment ReportMary Alwina TabasaОценок пока нет

- Department of Education: Learning Action Cell Narrative ReportДокумент12 страницDepartment of Education: Learning Action Cell Narrative ReportCristine G. LagangОценок пока нет

- 2 Neo-Classical and Modern Management TheoriesДокумент39 страниц2 Neo-Classical and Modern Management TheoriesYASH SANJAY.INGLEОценок пока нет

- Exploring Space Project MercuryДокумент16 страницExploring Space Project MercuryBob Andrepont100% (2)

- Cv-Mario AgritamaДокумент3 страницыCv-Mario Agritamahcmms2020Оценок пока нет

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership and Their Effects On Creativity in GroupsДокумент12 страницTransformational and Transactional Leadership and Their Effects On Creativity in Groupsnamugabo dauratОценок пока нет

- Aah Disinfection For Bakery ProductsДокумент5 страницAah Disinfection For Bakery ProductsbodnarencoОценок пока нет

- Manoj Kumar M Project MB182357 PDFДокумент79 страницManoj Kumar M Project MB182357 PDFManoj KumarОценок пока нет

- Syllabus: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, NashikДокумент5 страницSyllabus: Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, NashikRuchi HumaneОценок пока нет

- Local Media392447226283119720Документ78 страницLocal Media392447226283119720Apple James Orpiza IbitОценок пока нет

- Principles of Risk Risk Management Specimen Examination Guide v2Документ10 страницPrinciples of Risk Risk Management Specimen Examination Guide v2Anonymous qAegy6GОценок пока нет

- Implementation of Wave Effects in The Unstructured Delft3D Suite FinalДокумент93 страницыImplementation of Wave Effects in The Unstructured Delft3D Suite Finalferney orejuelaОценок пока нет

- Introduction to Sociology Course OutlineДокумент5 страницIntroduction to Sociology Course OutlineRayed RiasatОценок пока нет

- DPI Report On IDEA ComplianceДокумент15 страницDPI Report On IDEA ComplianceKeung HuiОценок пока нет

- Powerpoint Math 10Документ26 страницPowerpoint Math 10nimfa c, hinacayОценок пока нет

- Federico CosenzДокумент14 страницFederico Cosenzsergio londoñoОценок пока нет

- Ngss Science Integration LDC 9-12 Rubric-3Документ6 страницNgss Science Integration LDC 9-12 Rubric-3api-318937942Оценок пока нет

- M.Sc. Mathematics Course Structure: Year First Semester U Second Semester UДокумент3 страницыM.Sc. Mathematics Course Structure: Year First Semester U Second Semester UAbhishek UpadhyayОценок пока нет

- Mba Capstone ReportДокумент11 страницMba Capstone ReportKANCHAN DEVIОценок пока нет

- Marketing Research Study MaterialДокумент38 страницMarketing Research Study MaterialNisarg PatelОценок пока нет

- University of Health Sciences Lahore: Theory Date SheetДокумент1 страницаUniversity of Health Sciences Lahore: Theory Date SheetNayabОценок пока нет

- Sciencensw4 ch00Документ9 страницSciencensw4 ch00ryan.mundanmany58Оценок пока нет

- D. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Ruparrrrrel Colleg El Colleg El Colleg El Colleg El CollegeeeeeДокумент48 страницD. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Rupa D. G. Ruparrrrrel Colleg El Colleg El Colleg El Colleg El Collegeeeeerah98Оценок пока нет

- KEY IDEAS OF ABSTRACTS, PRÉCIS AND SUMMARIESДокумент2 страницыKEY IDEAS OF ABSTRACTS, PRÉCIS AND SUMMARIESGabrielle GeolingoОценок пока нет

- Microbiologist ResumeДокумент5 страницMicrobiologist Resumecprdxeajd100% (2)

- TM Deliver A Short Oral Presentation in English RefinedДокумент74 страницыTM Deliver A Short Oral Presentation in English RefinedYohanes ArifОценок пока нет

- Breadth RequirementsДокумент2 страницыBreadth RequirementsJulian ChoОценок пока нет

- Radcliffe-Brown A. R PDFДокумент12 страницRadcliffe-Brown A. R PDFSakshiОценок пока нет

- Attitude 3Документ19 страницAttitude 3DEVINA GURRIAHОценок пока нет

- Desert Survival TestДокумент2 страницыDesert Survival TestKaran BaruaОценок пока нет

- DISS Module 1Документ9 страницDISS Module 1Damie Emata LegaspiОценок пока нет