Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Measuring The Success of Strategic Initiatives

Загружено:

Veer SilharИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Measuring The Success of Strategic Initiatives

Загружено:

Veer SilharАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 29

Chapter Four: Measuring the Success

of Strategic Initiatives

LEARNING OUTCOMES

4.1. Compare efficiency IT metrics and effectiveness IT 4.3. List and describe four types of effectiveness IT

metrics. metrics.

4.2. List and describe five common types of efficiency 4.4. Explain customer metrics and their importance to

IT metrics. an organization.

I

n an effort to offer detailed information to all layers of management, General

Electric Co. (GE) invested $1.5 billion in employee time, hardware, software,

and other technologies to implement a real-time operations monitoring sys-

tem. GE’s executives use the new system to monitor sales, inventory, and savings

across its 13 different global business operations every 15 minutes. This allows GE

to respond to changes, reduce cycle times, and improve risk management on an

hourly basis instead of waiting for month-end or quarter-end reports. GE estimates

that the $1.5 billion investment will provide a 33 percent return on investment over

the five years of the project.13

Organizations spend enormous sums of money on IT to compete in today’s fast-

paced business environment. Some organizations spend up to 50 percent of their

total capital expenditures on IT. To justify expenditures on IT, an organization must

measure the payoff of these investments, their impact on business performance,

and the overall business value gained.

Efficiency and effectiveness metrics are two primary types of IT metrics. Effi-

ciency IT metrics measure the performance of the IT system itself including

throughput, speed, availability, etc. Effectiveness IT metrics measure the impact IT

has on business processes and activities including customer satisfaction, conver-

sion rates, sell-through increases, etc. Peter Drucker offers a helpful distinction be-

tween efficiency and effectiveness. Drucker states that managers “Do things right”

and/or “Do the right things.” Doing things right addresses efficiency—getting the

most from each resource. Doing the right things addresses effectiveness—setting

the right goals and objectives and ensuring they are accomplished.14

Effectiveness focuses on how well an organization is achieving its goals and ob-

jectives, while efficiency focuses on the extent to which an organization is using its

resources in an optimal way. The two—efficiency and effectiveness—are definitely

interrelated. However, success in one area does not necessarily imply success in the

other.

BENCHMARKING—BASELINING METRICS

Regardless of what is measured, how it is measured, and whether it is for the sake

of efficiency or effectiveness, there must be benchmarks, or baseline values the sys-

tem seeks to attain. Benchmarking is a process of continuously measuring system

results, comparing those results to optimal system performance (benchmark val-

ues), and identifying steps and procedures to improve system performance.

Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology 29

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 30

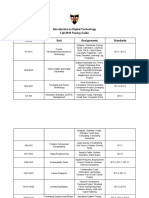

Consider e-government worldwide as an illustra-

Efficiency Effectiveness

tion of benchmarking efficiency IT metrics and effec-

1. United States (3.11) 1. Canada tiveness IT metrics (see survey results in Figure 1.19).

2. Australia (2.60) 2. Singapore From an effectiveness point of view, Canada ranks

3. New Zealand (2.59) 3. United States

number one in terms of e-government satisfaction of

its citizens. (The United States ranks third.) The sur-

4. Singapore (2.58) 4. Denmark

vey, sponsored by Accenture, also included such attri-

5. Norway (2.55) 5. Australia butes as CRM practices, customer-service vision, ap-

6. Canada (2.52) 6. Finland proaches to offering e-government services through

7. United Kingdom (2.52) 7. Hong Kong multiple-service delivery channels, and initiatives for

8. Netherlands (2.51) 8. United Kingdom identifying services for individual citizen segments.

9. Denmark (2.47) 9. Germany

These are all benchmarks at which Canada’s govern-

ment excels.15

10. Germany (2.46) 10. Ireland

In contrast, the United Nations Division for Public

Economics and Public Administration ranks Canada

FIGURE 1.19 sixth in terms of efficiency IT metrics. (It ranked the United States first.) This par-

Comparing IT Efficiency ticular ranking based purely on efficiency IT metrics includes benchmarks such as

and Effectiveness the number of computers per 100 citizens, the number of Internet hosts per 10,000

Metrics for citizens, the percentage of the citizen population online, and several other factors.

E-Government Therefore, while Canada lags behind in IT efficiency, it is the premier e-government

Initiatives provider in terms of effectiveness.16

Governments hoping to increase their e-government presence would bench-

mark themselves against these sorts of efficiency and effectiveness metrics. There

is a high degree of correlation between e-government efficiency and effectiveness,

although it is not absolute.

THE INTERRELATIONSHIPS OF EFFICIENCY AND EFFECTIVENESS

IT METRICS

Efficiency IT metrics focus on the technology itself. The most common types of

efficiency IT metrics include:

■ Throughput—the amount of information that can travel through a system at

any point in time.

■ Speed—the amount of time a system takes to perform a transaction.

■ Availability—the number of hours a system is available for use by customers

and employees.

■ Accuracy—the extent to which a system generates the correct results when

executing the same transaction numerous times.

■ Web traffic—including a host of benchmarks such as the number of page-

views, the number of unique visitors, and the average time spent viewing a

Web page.

■ Response time—the time it takes to respond to user interactions such as a

mouse click.

While these efficiency metrics are important to monitor, they do not always

guarantee effectiveness. Effectiveness IT metrics are determined according to an

organization’s goals, strategies, and objectives. Here, it becomes important to con-

sider the strategy an organization is using, such as a broad cost leadership strategy

(Wal-Mart for example), as well as specific goals and objectives such as increasing

new customers by 10 percent or reducing new product development cycle times to

six months. Broad, general effectiveness metrics include:

■ Usability—the ease with which people perform transactions and/or find in-

formation. A popular usability metric on the Internet is degrees of freedom,

which measures the number of clicks to get to desired information or process-

ing capabilities.

30 Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 31

■ Customer satisfaction—as measured by such benchmarks as satisfaction sur-

veys, percentage of existing customers retained, and increases in revenue dol-

lars per customer.

■ Conversion rates—the number of customers an organization “touches” for

the first time and convinces to purchase its products or services. This is a pop-

ular metric for evaluating the effectiveness of banner, pop-up, and pop-under

ads on the Internet.

■ Financial—such as return on investment (the earning power of an organiza-

tion’s assets), cost-benefit analysis (the comparison of projected revenues and

costs including development, maintenance, fixed, and variable), and break-

even analysis (the point at which constant revenues equal ongoing costs).

In the private sector, eBay is an organization that constantly benchmarks its

information technology efficiency and effectiveness. In 2003, eBay posted impres-

sive year-end results with revenues increasing 74 percent while earnings grew 135

percent. Maintaining constant Web site availability and optimal throughput per- eBay’s Web site

formance is critical to eBay’s success.17

Jupiter Media Metrix ranked eBay as the Web

site with the highest visitor volume (efficiency) in

2003 for the second year in a row, with an 80 per-

cent growth from the previous year. eBay averaged

4.5 million unique visitors during each week of

the holiday season that year with daily peaks ex-

ceeding 5 million visitors. To ensure constant

availability and reliability of its systems, eBay im-

plemented ProactiveNet, a performance measure-

ment and management-tracking tool. The tool al-

lows eBay to monitor its environment against

baseline benchmarks, which helps the eBay team

keep tight control of its systems. The new system

has resulted in improved system availability with a

150 percent increase in productivity as measured

by system uptime.18

Do not forget to consider the issue of security

while determining efficiency and effectiveness IT

metrics. When an organization offers its cus-

tomers the ability to purchase products over the

Internet it must implement the appropriate secu-

rity—such as encryption and Secure Sockets Lay-

ers (SSLs; denoted by the lock symbol in the lower right corner of a browser window

and/or the “s” in https). It is actually inefficient for an organization to implement

security measures for Internet-based transactions as compared to processing non-

secure transactions. However, an organization will probably have a difficult time at-

tracting new customers and increasing Web-based revenue if it does not implement

the necessary security measures. Purely from an efficiency IT metric point of view,

security generates some inefficiency. From an organization’s business strategy

point of view, however, security should lead to increases in effectiveness metrics.

Figure 1.20 provides a graph depicting the interrelationships between efficiency

and effectiveness. Ideally, an organization should operate in the upper right-hand

corner of the graph, realizing both significant increases in efficiency and effective-

ness. However, operating in the upper left-hand corner (minimal efficiency with in-

creased effectiveness) or the lower right-hand corner (significant efficiency with

minimal effectiveness) may be in line with an organization’s particular strategies. In

general, operating in the lower left-hand corner (minimal efficiency and minimal

effectiveness) is not ideal for the operation of any organization.

Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology 31

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 32

FIGURE 1.20 High

The Interrelationships

between Efficiency and

Effectiveness

Optimal area

Efficiency

in which to

operate

Low

Low Effectiveness High

DETERMINING IT EFFICIENCY AND EFFECTIVENESS

Stock market analysts tend to have a bias toward financial metrics. Clearly this em-

phasis is important—however, focusing only on financial measurements is limiting

since financial metrics are only one factor that an organization can use to deter-

mine IT effectiveness. Customer metrics assess the management of customer rela-

tionships by the organization. These effectiveness metrics typically focus on a set of

core measurements including market share, customer acquisition, customer satis-

faction, and customer profitability.

Traffic on the Internet retail site for Wal-Mart has grown 66 percent in the last

year. The site has over 500,000 visitors daily, 2 million Web pages downloaded daily,

6.5 million visitors per week, and over 60,000 users logged on simultaneously. Wal-

Mart’s primary concern is maintaining optimal performance for online transac-

tions. A disruption to the Web site directly affects the company’s bottom line and

customer loyalty. The company monitors and tracks the hardware, software, and

network running the company’s Web site to ensure high quality of service, which

saved the company $1.1 million dollars in 2003.19

Customers are primarily concerned with the quality of service they receive from

an organization. Anyone using the Internet knows that it is far from perfect and

often slow. One of the biggest problems facing Internet users is congestion caused

by capacity too small to handle large amounts of traffic. Corporations are continu-

ally benchmarking and monitoring their systems in order to ensure high quality of

service. The most common quality of service metrics that are benchmarked and

monitored include throughput, speed, and availability.

A company must continually monitor these behaviors to determine if the system

is operating above or below expectations. If the system begins to operate below ex-

pectations, system administrators must take immediate action to bring the system

back up to acceptable operating levels. For example, if a company suddenly began

taking two minutes to deliver a Web page to a customer, the company would need

to fix this problem as soon as possible to keep from losing customers and ultimately

revenue.

Web Traffic Analysis

Most companies measure the traffic on a Web site as the primary determinant of

the Web site’s success. However, a lot of Web site traffic does not necessarily indi-

cate large sales. Many organizations with lots of Web site traffic have minimal sales.

A company can go further and use Web traffic analysis to determine the revenue

generated by Web traffic, the number of new customers acquired by Web traffic, any

reductions in customer service calls resulting from Web traffic, and so on. The Yan-

kee Group reports that 66 percent of companies determine Web site success solely

by measuring the amount of traffic. New customer acquisition ranked second on

the list at 34 percent, and revenue generation ranked third at 23 percent.20

32 Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 33

Analyzing Web site traffic is one way organizations can understand the effective-

ness of Web advertising. A cookie is a small file deposited on a hard drive by a Web

site containing information about customers and their Web activities. Cookies al-

low Web sites to record the comings and goings of customers, usually without their

knowledge or consent. A click-through is a count of the number of people who visit

one site and click on an advertisement that takes them to the site of the advertiser.

A banner ad is a small ad on one Web site that advertises the products and services

of another business, usually another dot-com business. Advertisers can track how

often customers click on banner ads resulting in a click-through to their Web site.

Often the cost of the banner ad depends on the number of customers who click on

the banner ad. Tracking the number of banner ad clicks is a great way to begin to

understand the effectiveness of the ad on its target audience.

Tracking effectiveness based on click-throughs guarantees exposure to target

ads; however, it does not guarantee that the visitor liked the ad, spent any substan-

tial time viewing the ad, or was satisfied with the information contained in the ad.

In order to help understand advertising effectiveness, interactivity measures are

tracked and monitored. Interactivity measures the visitor interactions with the tar-

get ad. Such interaction measures include the duration of time the visitor spends

viewing the ad, the number of pages viewed, and even the number of repeat visits

to the target ad. Interactivity measures are a giant step forward for advertisers,

since traditional methods of advertising through newspapers, magazines, outdoor

such as billboards and buses, and radio and television provide no way to track

effectiveness metrics. Interactivity metrics measure actual consumer activities,

something that was impossible to do in the past and provides advertisers with

tremendous amounts of useful information.

The ultimate outcome of any advertisement is a purchase. Knowing how many

visitors make purchases on a Web site and the dollar amount of the purchases cre-

ates critical business information. It is easy to communicate the business value of

a Web site or Web application when an organization can tie revenue amounts and

new customer creation numbers directly back to the Web site, banner ad, or Web

application.

Behavioral Metrics

Firms can observe through click-stream data the exact pattern of a consumer’s nav-

igation through a site. Click-stream data can reveal a number of basic data points

on how consumers interact with Web sites. Metrics based on click-stream data in-

clude:

■ The number of page views (i.e., the number of times a particular page has

been presented to a visitor)

■ The pattern of Web sites visited, including most frequent exit page and most

frequent prior Web sites

■ Length of stay on the Web site

■ Dates and times of visits

■ Number of registrations filled out per 100 visitors

■ Number of abandoned registrations

■ Demographics of registered visitors

■ Number of customers with shopping carts

■ Number of abandoned shopping carts

Figure 1.21 provides definitions of common metrics based on click-stream data. To

interpret such data properly, managers try to benchmark against other companies.

For instance, consumers seem to visit their preferred Web sites regularly, even

checking back to the Web site multiple times during a given session. Consumers

tend to become loyal to a small number of Web sites, and they tend to revisit those

Web sites a number of times during a particular session.

Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology 33

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 34

FIGURE 1.21

Visitor Visitor Metrics

Web Site Metrics

Unidentified visitor A visitor is an individual who visits a Web site. An “unidentified visitor”

means that no information about that visitor is available.

Unique visitor A unique visitor is one who can be recognized and counted only once

within a given period of time. An accurate count of unique visitors is not

possible without some form of identification, registration, or

authentication.

Session visitor A session ID is available (e.g., cookie) or inferred by incoming address

plus browser type, which allows a visitor’s responses to be tracked within

a given visit to a Web site.

Tracked visitor An ID (e.g., cookie) is available which allows a user to be tracked across

multiple visits to a Web site. No information, other than a unique

identifier, is available for a tracked visitor.

Identified visitor An ID is available (e.g., cookie or voluntary registration), which allows a

user to be tracked across multiple visits to a Web site. Other information

(name, demographics, possibly supplied voluntarily by the visitor) can be

linked to this ID.

Exposure Exposure Metrics

Page exposures The number of times a particular Web page has been viewed by visitors

(page-views) in a given time period, without regard to duplication.

Site exposures The number of visitor sessions at a Web site in a given time period,

without regard to visitor duplication.

Visit Visit Metrics

Stickiness (visit The length of time a visitor spends on a Web site. Can be reported as an

duration time) average in a given time period, without regard to visitor duplication.

Raw visit depth (total The total number of pages a visitor is exposed to during a single visit to a

Web pages exposure Web site. Can be reported as an average or distribution in a given time

per session) period, without regard to visitor duplication.

Visit depth (total The total number of unique pages a visitor is exposed to during a single

unique Web pages visit to a Web site. Can be reported as an average or distribution in a

exposure per session) given time period, without regard to visitor duplication.

Hit Hit Metrics

Hits When visitors reach a Web site, their computer sends a request to the

site’s computer server to begin displaying pages. Each element of a

requested page (including graphics, text, interactive items) is recorded by

the Web site’s server log file as a “hit.”

Qualified hits Exclude less important information recorded in a log file (such as error

messages, etc.).

Evolving technologies are continually changing the speed and form of business

in almost every industry. Organizations spend an enormous amount of money on

IT in order to remain competitive. Some organizations spend up to 50 percent of

their total capital expenditures on IT investments. More than ever, there is a need

to understand the payoff of these large IT investments, the impact on business per-

formance, and the overall business value gained with the use of technology. One of

the best ways to demonstrate business value is by analyzing an IT project’s effi-

ciency and effectiveness metrics.

34 Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology

*

haa83019_unit01 10/22/04 1:29 PM Page 35

OPENING CASE STUDY QUESTIONS

1. Formulate a strategy for how Levi’s can use efficiency IT metrics to improve its business.

2. Formulate a strategy for how Levi’s can use effectiveness IT metrics to improve its business.

Chapter Four Case: How Do You Value Friendster?

Jonathan Abrams is keeping quiet about how he is going to generate revenue from his Web

site, Friendster, which specializes in social networking. Abrams is a 33-year-old Canadian

software developer whose experiences include being laid off by Netscape and then moving

from one start-up to another. In 2002, Abrams was unemployed, not doing well financially, and

certainly not looking to start another business when he developed the idea for Friendster. He

quickly coded a working prototype and watched in amazement as his Web site took off.

The buzz around social networking start-ups has recently been on the rise. A number of

high-end venture capital (VC) firms, including Sequoia and Mayfield, have invested more than

$40 million into social networking start-ups such as LinkedIn, Spoke, and Tribe Networks.

Friendster received over $13 million in VC capital from Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, Byers, and

Benchmark Capital, which reportedly valued the company at $53 million—a startling figure for

a company that had yet to generate even a single dime in revenue.

A year after making its public debut, Friendster is one of the largest social networking Web

sites, attracting over 5 million users and receiving over 50,000 page-views per day. The ques-

tion is how do efficiency metrics, such as Web traffic and page-views, turn into cash flow?

Everyone is wondering how Friendster is going to begin generating revenue.

The majority of Abrams’s competitors make their money by extracting fees from their sub-

scribers. Friendster is going to continue to let its subscribers meet for free but plans to charge

them for premium services such as the ability to customize their profile page. The company

also has plans to extend beyond social networking to an array of value-added services such

as friend-based job referrals and classmate searches. Abrams is also looking into using his

high-traffic Web site to tap into the growing Internet advertising market.

Abrams does not appear concerned about generating revenue or about potential competi-

tion. He states, “Match.com has been around eight years, has 12 million users, and has spent

many millions of dollars on advertising to get them. We’re a year old, we’ve spent zero dollars

on advertising, and in a year or less, we’ll be bigger than them—it’s a given.”

The future of Friendster is uncertain. Google recently offered to buy Friendster for $30 mil-

lion even though there are signs, both statistical and anecdotal, that Friendster’s popularity

may have peaked.21

Questions

1. How could you use efficiency IT metrics to help place a value on Friendster?

2. How could you use effectiveness IT metrics to help place a value on Friendster?

3. Explain how a venture capital company can value Friendster at $53 million when the

company has yet to generate any revenue.

4. Explain why Google would be interested in buying Friendster for $30 million when the

company has yet to generate any revenue.

Unit 1 Achieving Business Success through Information Technology 35

*

Вам также может понравиться

- Factors Affecting Implementation of Information Systems Success and FailureДокумент11 страницFactors Affecting Implementation of Information Systems Success and FailureAvijit Dutta ShaonОценок пока нет

- 12.balanced Scorecard Case Study PDFДокумент27 страниц12.balanced Scorecard Case Study PDFandihasadОценок пока нет

- Summary of Nicole Forsgren PhD, Jez Humble & Gene Kim's AccelerateОт EverandSummary of Nicole Forsgren PhD, Jez Humble & Gene Kim's AccelerateОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Information Technology On PDFДокумент8 страницThe Impact of Information Technology On PDFzameerahmadОценок пока нет

- 2021 Strategic Roadm 732455 NDXДокумент31 страница2021 Strategic Roadm 732455 NDXMiguel EspinozaОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Accounting Information Systems: SciencedirectДокумент14 страницInternational Journal of Accounting Information Systems: Sciencedirectshubham maneОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting The Successful Implementation of ICT Projects in Government-With-Cover-Page-V2Документ11 страницFactors Affecting The Successful Implementation of ICT Projects in Government-With-Cover-Page-V2Banjani KalansooriyaОценок пока нет

- 2017 - Assessment of E-Governance Projects (Gaps - Constructs)Документ10 страниц2017 - Assessment of E-Governance Projects (Gaps - Constructs)SheenjeeОценок пока нет

- SAD Module 1 Introduction To System Analysis and DesignДокумент38 страницSAD Module 1 Introduction To System Analysis and DesignPam VillegasОценок пока нет

- Tut Sol W1 COIS20024 2011 V1Документ8 страницTut Sol W1 COIS20024 2011 V1Santhu KsskОценок пока нет

- Future of CIOДокумент15 страницFuture of CIONazeerrОценок пока нет

- 1.importance of ISДокумент35 страниц1.importance of ISAmewu Mensah EmmanuelОценок пока нет

- A Study of The Business Value of It General Controls in ChinaДокумент15 страницA Study of The Business Value of It General Controls in ChinaPuguh JayadiningratОценок пока нет

- Whitepaper+ +Next+Generation+SystemsДокумент13 страницWhitepaper+ +Next+Generation+SystemsadnanakdrОценок пока нет

- IT GOVERNANCE - Performance Measurement PDFДокумент45 страницIT GOVERNANCE - Performance Measurement PDFDimas Bhoby HandokoОценок пока нет

- A Cost Control System Development - A Collaborative Approach For Small and Medium-Sized ContractorsДокумент8 страницA Cost Control System Development - A Collaborative Approach For Small and Medium-Sized Contractorsntl9630Оценок пока нет

- Status Measured With An IT BSC Maturity ModelДокумент10 страницStatus Measured With An IT BSC Maturity Modellgg1960789Оценок пока нет

- The Critical Success Factors Study For E-Government ImplementationДокумент11 страницThe Critical Success Factors Study For E-Government ImplementationAnnisa Lisa AndriyaniОценок пока нет

- AUDCISДокумент50 страницAUDCIS뿅아리Оценок пока нет

- Questions From Chap 1 and Rugby Case Assignment 2Документ4 страницыQuestions From Chap 1 and Rugby Case Assignment 2Syeda Wahida SabrinaОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Information Technology On Accounting and Finance 1Документ12 страницThe Impact of Information Technology On Accounting and Finance 1Samsung IphoneОценок пока нет

- Audit of IT Governance Based On COBIT 5 Assessments: A Case StudyДокумент8 страницAudit of IT Governance Based On COBIT 5 Assessments: A Case StudyFaisal Fahri FerdiansyahОценок пока нет

- Citigroup Case StudyДокумент6 страницCitigroup Case StudyIrsyad AhmadiОценок пока нет

- 1.1 Literature Review: Mcconnell International'S Risk E-Business: Seizing The Opportunity of Global E-ReadinessДокумент10 страниц1.1 Literature Review: Mcconnell International'S Risk E-Business: Seizing The Opportunity of Global E-Readinesspankaj.mdn6718Оценок пока нет

- Demonstrating ROI Greg WassДокумент10 страницDemonstrating ROI Greg Wasse.RepublicОценок пока нет

- #1 Introduction To Information System - 2020Документ36 страниц#1 Introduction To Information System - 2020anshariОценок пока нет

- Evaluation of Erp Implementation On Firm Performance A Case Study of AtntДокумент8 страницEvaluation of Erp Implementation On Firm Performance A Case Study of AtntrehankalsekarОценок пока нет

- The IT Audit ResearchДокумент3 страницыThe IT Audit ResearchAnnie TranОценок пока нет

- The Challenges of Knowledge Management, Solutions and TechnologyДокумент18 страницThe Challenges of Knowledge Management, Solutions and TechnologyZahra ArdanaОценок пока нет

- At The MentionДокумент26 страницAt The MentiontazevansОценок пока нет

- Performance Measurement of Information Technology Governance: A Case StudyДокумент7 страницPerformance Measurement of Information Technology Governance: A Case StudyCosti AldalouОценок пока нет

- Aconex Report Global Industry CouncilДокумент22 страницыAconex Report Global Industry CouncilMohammad SabbaghОценок пока нет

- E GovernanceДокумент50 страницE GovernancePavani ReddyОценок пока нет

- Seven Lessons On How Technology Transformations Can Deliver ValueДокумент9 страницSeven Lessons On How Technology Transformations Can Deliver ValueVladimir KirovskiОценок пока нет

- ICT Value For Money Indicators Guidance 1) IntroductionДокумент26 страницICT Value For Money Indicators Guidance 1) IntroductionHenry HoveОценок пока нет

- Dis511 Jan-Apr 2020 Introduction To Information Systems - Lect 1Документ11 страницDis511 Jan-Apr 2020 Introduction To Information Systems - Lect 1Wycliff OtengОценок пока нет

- Bab 7 Effects: Tasks, Processes and Structures: Teknologi Informasi Dan KomunikasiДокумент14 страницBab 7 Effects: Tasks, Processes and Structures: Teknologi Informasi Dan KomunikasiSyahwa RamadhanОценок пока нет

- Submitted By:-: Part - AДокумент9 страницSubmitted By:-: Part - ANiranjan DikshitОценок пока нет

- Use of The Balanced Scorecard For ICT Performance ManagementДокумент14 страницUse of The Balanced Scorecard For ICT Performance ManagementHenry HoveОценок пока нет

- CameraReadyPaperSubmission ICBMITOct2015Документ7 страницCameraReadyPaperSubmission ICBMITOct2015David BermudezОценок пока нет

- Core Model of Information Technology Governance System Design in Local GovernmentДокумент12 страницCore Model of Information Technology Governance System Design in Local GovernmentTELKOMNIKAОценок пока нет

- IT in ManagementДокумент222 страницыIT in ManagementPallu KaushikОценок пока нет

- Information Technology For Management Digital Strategies For Insight Action and Sustainable Performance 10th Edition Turban Solutions ManualДокумент35 страницInformation Technology For Management Digital Strategies For Insight Action and Sustainable Performance 10th Edition Turban Solutions Manualalexanderstec100% (9)

- Computer Application PsdaДокумент5 страницComputer Application PsdaPAWANI ASWANIОценок пока нет

- Summary MIS ArticlesДокумент11 страницSummary MIS ArticleslakjsdbfОценок пока нет

- Corrections Intelligence. Central CollaborationДокумент29 страницCorrections Intelligence. Central CollaborationJack RyanОценок пока нет

- Big Data Management and Cloud ComputingДокумент7 страницBig Data Management and Cloud Computingserkalem yimerОценок пока нет

- Cloud HypothesisДокумент17 страницCloud HypothesisrahulbwОценок пока нет

- A Study of The Effect of Organizational IQ On IT Investment and ProductivityДокумент4 страницыA Study of The Effect of Organizational IQ On IT Investment and ProductivityJean-Loïc BinamОценок пока нет

- Use of IT in ControllingДокумент19 страницUse of IT in ControllingSameer Sawant50% (2)

- The Effect of Implementation of Report Online Application On User Satisfaction and Operational PerformanceДокумент11 страницThe Effect of Implementation of Report Online Application On User Satisfaction and Operational PerformanceInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Whitepaper Roi of Devops Transformation 2020 Google CloudДокумент40 страницWhitepaper Roi of Devops Transformation 2020 Google CloudDavid Pereira (Gigabaite)Оценок пока нет

- Week 1Документ21 страницаWeek 1Yacoub Abu-dahouОценок пока нет

- A Case Study On General Electric Consumer ProductsДокумент17 страницA Case Study On General Electric Consumer ProductsTrần Lê DungОценок пока нет

- Apoyos Semana 14 SITDДокумент52 страницыApoyos Semana 14 SITDscribdjualoОценок пока нет

- Ibm Data Center StudyДокумент20 страницIbm Data Center StudyAditya Soumava100% (1)

- Atde 16 Atde210095Документ10 страницAtde 16 Atde210095Josip StjepandicОценок пока нет

- The Power To Predict and Prevent: Infrastructure Monitoring 101Документ23 страницыThe Power To Predict and Prevent: Infrastructure Monitoring 101whizboyОценок пока нет

- Module 7 The Internet Part 2Документ27 страницModule 7 The Internet Part 2Jenrose FernandezОценок пока нет

- Facebook CommerceДокумент68 страницFacebook CommerceDigital LabОценок пока нет

- DS 160 GuidelinesДокумент3 страницыDS 160 GuidelinesChandan KumarОценок пока нет

- ATS TemplateДокумент1 страницаATS TemplateYuvarajОценок пока нет

- HTML5 Application Development Fundamentals PDFДокумент297 страницHTML5 Application Development Fundamentals PDFNeoff2240% (1)

- INTERNSHIP PRESENTATION - Harshitha - 2020Документ17 страницINTERNSHIP PRESENTATION - Harshitha - 2020Sanitha MichailОценок пока нет

- Creative Writing: Quarter 2 - Module 4 The Different Orientations of Creative WritingДокумент25 страницCreative Writing: Quarter 2 - Module 4 The Different Orientations of Creative WritingPHEBE ANTIQUINA86% (7)

- Smart Connector Users GuideДокумент140 страницSmart Connector Users GuideNike NikkiОценок пока нет

- Ahmed Elsayed Salem ResumeДокумент2 страницыAhmed Elsayed Salem ResumeAhmed_Salem_966Оценок пока нет

- Mis Assignment Case StudyДокумент20 страницMis Assignment Case StudyMwai Wa KariukiОценок пока нет

- Pos Laju Track Trace Information System-2Документ19 страницPos Laju Track Trace Information System-2Naim AhmadОценок пока нет

- Automated Library Management SystemДокумент12 страницAutomated Library Management SystemHarshal ShendeОценок пока нет

- Copyright LawДокумент21 страницаCopyright LawBelle MadreoОценок пока нет

- Vacation Rental Marketing Checklist: Here's What You Need To Succeed in Marketing Your Vacation RentalДокумент17 страницVacation Rental Marketing Checklist: Here's What You Need To Succeed in Marketing Your Vacation RentalMuse ManiaОценок пока нет

- Top 10 Science Magazines, Publications & Ezines To Follow in 2019Документ1 страницаTop 10 Science Magazines, Publications & Ezines To Follow in 2019Mehmet ZiysОценок пока нет

- OFFICIAL PRAGMATIC PLAY ONLINE LOGINdtjwv PDFДокумент4 страницыOFFICIAL PRAGMATIC PLAY ONLINE LOGINdtjwv PDFpeakbamboo58Оценок пока нет

- AssignmentДокумент6 страницAssignmentPhoebe BongОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Web EngineeeringДокумент112 страницChapter 1 Web EngineeeringSushant NandwaniОценок пока нет

- Cer2015 Proceedings01 PDFДокумент306 страницCer2015 Proceedings01 PDFDanica PirslОценок пока нет

- Multi Farm Sharepoint 2013 PDFДокумент1 страницаMulti Farm Sharepoint 2013 PDFRodrigo PeluffoОценок пока нет

- The Six Simple Principles of Viral Marketing: by Dr. Ralph F. Wilson, E-Commerce ConsultantДокумент2 страницыThe Six Simple Principles of Viral Marketing: by Dr. Ralph F. Wilson, E-Commerce Consultantanjaliap15Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To Digital Technology Fall 2018 Pacing Guide Dates Unit Assignments StandardsДокумент3 страницыIntroduction To Digital Technology Fall 2018 Pacing Guide Dates Unit Assignments StandardsTiffanyОценок пока нет

- Measuring The Degree of Corporate Social Media Use PDFДокумент19 страницMeasuring The Degree of Corporate Social Media Use PDFsocialmedia3Оценок пока нет

- Hawaii Legislature Website Guide Capitol - Hawaii.gov: A Gateway To The CapitolДокумент8 страницHawaii Legislature Website Guide Capitol - Hawaii.gov: A Gateway To The CapitolHNNОценок пока нет

- Web Tracker Integration GuideДокумент12 страницWeb Tracker Integration GuideEmmanuel Peña FloresОценок пока нет

- It3401 Web Essentials SyllabusДокумент2 страницыIt3401 Web Essentials SyllabusBala SubramanianОценок пока нет

- Bring Your Own LaptopДокумент5 страницBring Your Own LaptopSalsabila BalqisОценок пока нет

- Social Media PolicyДокумент8 страницSocial Media PolicyJeff MorrisОценок пока нет

- Security Baseline For Web HostingДокумент4 страницыSecurity Baseline For Web Hostingss rajanОценок пока нет

- OSINTДокумент49 страницOSINTMARCUS VINICIUSОценок пока нет