Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

If I Leave Here Tomorrow: Pathways

Загружено:

Brad KingАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

If I Leave Here Tomorrow: Pathways

Загружено:

Brad KingАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

PATHWAYS

by RHETT UMPHRESS

To my mom, who will be there for me no matter where I go.

took a seat in the office, if thats what you could call it. I could stretch out my 6-foot, 2-inch frame and touch both walls. Add in the desk, computer, a few chairs and a bookshelf, and there wasnt a lot of room to work with. Do you have an idea where you want to go for college, my high school advisor asked. She was a small-framed woman but held herself with a large sense of authority. It had been three years since I had any meaningful conversation with her. As I entered my senior year at Bloomington North High School in Indiana in August 2003, she now wanted to know what my plans were. No, I really didnt know what awaited me at the end of the school year, I thought. College was always on the agenda. I had received straight As all through high school without maximum exertion. The four years after high school would be spent in classrooms, I just hadnt given much thought to where those classrooms would be and what Id be doing in them. All my other friends had plans beginning to unfold. They had sent applications and essays already. The admissions staff at their favorite colleges the University of Washington-St. Louis, Stanford University, even my hometowns Indiana University knew who they were and why they wanted to go to school there. Few people outside of the walls of my high school had ever heard of me. Of course, I couldnt say that to my guidance counselor. Those kinds of comments elicit long meetings, for which I had no particular stomach. Instead, I mumbled something about starting to look, hoping to end the conversation as soon as possible. Undaunted, the adviser went on, telling me about the importance of upcoming deadlines and how I needed to start sending applications. All I really wanted was to get back to class. The future was hard, but classes

were easy. I loved being in the classroom. I loved to learn new things, and after I gave the advisor a vague promising of starting my search, she released me back into the wild. * * *

It was always cold at the end of the marching band season. But the season wasnt supposed to be ending before the really bitter cold set in. As we prepared for the regionals performance at Jeffersonville High School, located in the southeast corner of Indiana, my schools band expected to qualify for state finals. Wed qualified the year before based on our strong musical performance, and we thought we had mastered the visual components enough to ensure we would not be ending our season on this cold, October night. Yet an unfortunate placement being required to perform early in the day and hoping our score would hold up meant it would be difficult to be among the top five ensembles out of the 20 groups performing. Hours after wed marched off the football field and the final band performed, we sat, together, on the cold metal bleachers, hoping to hear our schools name called. Gone were the underdog thoughts. We werent just happy to be there; we came to prove we belonged. Minutes later, the announcers friendly tenor boomed over the loudspeakers around the stadium. He read the list of names, a list that didnt include us, and we sat. We hadnt been picked. Four months of hard work felt pointless at that moment. Silently. I watched members from the other schools hug and celebrate, rejoicing in the fact that their season went on as our came crashing to an end. I thought marching in the RCA Dome home, at the time, to NFLs Indianapolis Colts franchise was going to be the reward for four years of hard work and development. Instead, I had to know that my last competition was on a random high school football field. A feeling of numbness washed over me. We walked back to the buses that would return us home, that would bring me home for the last time as a member of the marching band, and I didnt want to admit that it was over. I wanted to find a way to keep performing, to keep my music career going before high school ended. After every performance, we waited for Mr. Wilson, the marching band director, to get our final scores and judges comments. It was a chance to unwind as we hung around the buses and equipment van. This time, the band split into different groups: the seniors and the rest of the band.

The larger group were laughing and gossiping, the typical banter of high school students. Many had already moved on from the disappointment of the moment. For many of the seniors, me included, there was no interest in joining the fun and games. The numb feeling continued to pervade me as I was forced to face the reality that I was at the end of competitive marching the primary activity to which I had devoted my high school days. After avoiding the thoughts of the future for so long, I would have to address what would come after this. There was nothing else to do otherwise. Ms. Stockhouse, another band director, came over to me, checking if I was okay. I admitted that I was sad that I would not be able to march anymore. There always chances to march in college, she said. My closest friends were all giving up their instruments at the end of the school year, and I just figured that I would too. This was the first time I had ever thought about playing beyond high school. I felt as if I hadnt given enough time to music to feel that I had fulfilled my path with it. I had to find a way to keep the music playing. * * *

By the spring of 2004, I was standing in the post office with two envelopes, finalizing a very difficult choice. Id taken the advice of Ms. Stockhouse. Instead of giving up my instrument, Id decided that I wasnt quite ready to quit music just yet. I had spent the past few months auditioning at music schools and had finally been chosen by Ball State University, a mid-sized Midwestern university nestled between Indianapolis and Ft. Wayne. However, I was standing in the fluorescent-lit post office, about to drop off one envelope to notify BSU that I would not be attending the school in the fall, despite being selected to join the School of Music where I would have pursued music education. Simultaneously, I dropped the envelope that finalized my admission to Indiana University. As I walked out of the post office and across the parking lot toward my red, 1980s Ford Taurus, a numbness washed over me. Entering the car, I looked over at the girl in the passenger seat my girlfriend, Katie. I had turned down Ball States offer because of her. She tried to be comforting, but her attempts were unsuccessful. The best choice for us, she said, was to attend IU together. While it may have been good for our relationship, the letter I was mailing to Ball State would end my dream of being a musician. While I could dabble in music as a hobby at IU, one of the top music programs in the country, I

wouldnt have the opportunity to join the School of Music there. I wouldnt make the cut. Just before I sent my decision in, I pleaded with Katie to reconsider. I told her that we could make it work, that the two hours between universities wasnt insurmountable. When forced to make a choice, though, I was going to pick her. I had found someone willing to be with me, and the thought of losing her and going somewhere new was too much for me to handle. Being completely alone was a worse fate than giving up music. So I lied. I said that IU made sense for me. To justify it to others, I would say that I needed to broaden my horizons and continue to explore. It was easier that way, a tactic Id deployed with my guidance counselor and countless others in between. Im not a fighter. I dont like confrontation. But there were no lies in the car, and tears came flooding out. My girlfriend didnt understand. She couldnt understand, because I never told her. I never told anybody. Id simply floated through life, avoiding confrontation, avoiding decisions. Although I had given up on pursuing music, I didnt know what else to do with my college career. So other than a few core classes math and public speaking I enrolled in music courses at Indiana. * * *

Less than four months later, I was headed to my first music theory class, due to a loophole in IUs scheduling that allowed me to take 100-level courses despite not being accepted to the School of Music. The auditorium-style room was dimly lit, with enough light to read your notes and navigate the stairs while not taking away from the focus of the room down front, where the professor would lead the lecture. The room held 150 people, but this class had 100 students, so gaps of empty seats were scattered throughout the room. I didnt know anyone, having not taken part in orientation or any of the other chances to meet and greet with fellow students. Orientation was divided by majors, so while I was intermixed with the exploratory, or undecided, students, the rest of the musicians were mingling. I was living at home, so meeting new friends in the dorms was out too. Instead, I found a lonely corner of the room with enough space to ensure I wouldnt be forced into conversation. In my head, it was me against the class. I was convinced that being the best student in that class would prove I belonged, that I was as good as some of the best college musicians in the country. It wouldnt prove much, though. No matter how good I did in the class, I would never be welcomed into the School

of Music. The IU School of Music had four concert bands. The top three the Wind Ensemble, Symphonic Band and Concert Band were made up of music majors. Since I wasnt in the program, my only option was to join the AllCampus Band, a collection of students from a variety of majors who joined the ensemble in order to keep playing an instrument. After feeling overwhelmed by my music theory class, I had the opposite reaction to the All-Campus Band. While this ensemble was enough for them, I was unsatisfied by playing the same caliber of music I had in high school. There wasnt the challenge I was looking for through a college ensemble. Our weekly rehearsals in the large, concrete-filled room didnt provide the joy it had before. As I sat in my seat during the rehearsal, I was antsy more than anything. I didnt feel the challenge I had experienced while performing in high school. This was more of a tedium, a tangential connection to what I wanted to be doing. My motivation to use the ensemble for improvement didnt exist, because I didnt think I would get anything from being in the group. I had said I was going to give up music when I came to IU, but taking these classes served to scratch the itch for that career. I was always thinking about going to Ball State. I didnt enjoy living at home; it didnt feel like the college experience. Music was the only thing I could see myself doing at that moment, but I would have to leave the university if I was going to fulfill my calling. Which brought me back to Katie. For the entire school year, I tried to get her to see that I was unhappy staying in Bloomington. I longed to go to Ball State and actually be part of a program that made me feel invited. Slowly but surely, I wore her down. By the time the spring semester rolled around, she had realized that I wasnt going to stop pushing, and when I contacted Ball State to let them know I would be joining the university in the fall of 2005, I was ecstatic. I went to my advising office in the Honors College at IU, a red house that had been poorly converted into offices. Everything about the inside felt as if someone had thrown in a few desks, delegated offices to each adviser, and called it a success. I walked up the narrow staircase to my adviser. His name was Nigel, and he was from New Zealand with a heavy accent to prove it. Just hearing him talk could put a smile on your face. I told Nigel that I would be leaving the university at the end of the term and that I needed to know what paperwork would be required to finalize the process. No paperwork, he said. Thanks for letting me know. I was surprised to hear that, but it almost seemed appropriate. The university

had left no mark on me, other than a yearning for something different, and I had left no mark on it. My departure would be unnoticed; my time at the university nothing more than a few cashed checks and transferred credits. * * *

While my girlfriend had let me leave Bloomington and go to Ball State, I hadnt realized the conditions that would be put on me. I was under orders to come home every weekend, and at first, I was obedient, but the expectations were becoming unbearable. I would be invited to spend time with people on Fridays and Saturdays, but I would make up excuses as to why I wouldnt be available. I felt embarrassed by my inability to be honest about what I wanted to do and what I was doing. I wasnt making friends at Ball State because I would always disappear on the weekends, and eventually returning home to spend time with my girlfriend became more of a chore than anything else. We had been moving in different directions for a while. I wanted to fully commit to being at Ball State, while she was trying to pull me along in Bloomington even though we were hours apart. I knew that the next time I went home I would be breaking up with her. During the two-hour drive from Muncie to Bloomington on a Friday night in September, I tried to think of the perfect words to say to soften the blow. Imaginary scenarios whether it was the amicable split-up or a rage-filled conclusion played through my mind. I still cared about her, and hurting her was not what I was trying to do. I arrived in Bloomington and headed to her apartment complex. She was staying on the first floor with her roommate and dog. Two friends of ours lived next door. As I entered the apartment, I forced some casual conversation with my girlfriend and our friends before letting her know that we needed to talk. Her roommate was home, but the friends were gone so we slipped over to the neighboring apartment to get some privacy. The apartment wasnt very wide, but it stretched back a decent way. From the light of the single desk lamp that was turned on, the far side of the apartment vanished into darkness. After we both took a seat on the futon, I dropped the bombshell. I dont think we should see each other anymore. Katies first reaction was confusion, followed quickly by tears. But those quickly turned back into the familiar shouting that I had grown numb to over the years. How could you? she yelled, pacing through the apartment. As she walked

back and forth, in and out of the light, she became less of the person I had dated off-and-on for more than five years and was more of a silhouette in the dim light. I could feel her leaving my life as I watched. I, on the other hand, stayed motionless on the couch. I tried to find the words that would make things better, but they dont exist. I tried to stay stoic, not wanting to relent to her pleas for another chance. I knew that I was cutting my primary link to my hometown at this point and coming back to Bloomington would never be the same. I felt like the worst person in the world. I knew I was doing the right thing for me, but in that moment, all I could about was the fact that I had crushed someone I still cared about. Finally, I was told to leave, and I slinked out of the apartment.

hree-and-a-half years later, I was in the wrong place again. Id transferred to Ball State University in 2005 and joined the music education program. I enjoyed performing music, but I knew that my ability wasnt at a level where I would be able to join a symphony orchestra and there arent many other ways to make money playing the tuba. Music education seemed to make sense. I had gleaned so much from my high school band teachers that I thought I could pass the gift along. Four years of learning about what it takes to be a teacher had shown me that it wasnt as glamorous as I had envisioned through my rose-colored glasses. But by the spring of 2008, I was finishing my final undergraduate semester on campus, and I was miserable. I had no interest in teaching. Teaching felt like a tedium I just put up with. My day-to-day was more about surviving than developing skills or preparing to join the work force. The final straw was the torment I went through each time I would be put in front of a class and forced to teach. I was assigned to work at one of the middle schools in neighboring Anderson, Indiana. I was visiting the school three times per week and teaching a variety of lessons. Even though it was just a collection of 12- and 13-year-olds, I was afraid of them. I would stumble through my explanations, often having to repeat myself because of my lack of clarity. Awkward pauses as I tried to plan my way from A to B in my lessons were the norm. I wasnt ready to be a teacher, yet I was near the end anyway. In the fall, I was in my final semester as a student teacher at Muncie Central High School, just minutes away from the university at which I had spent the previous three years. Student teaching at Muncie Central made for another easy choice. The demands of the high school teachers, Bill Pritchett and Clay

Arnett, I worked with werent stringent and I didnt need to do much beyond staying out of trouble to get their modest approval. While they had come in with higher expectations, I managed to skate by with just enough effort not to feel out of my comfort zone. There were six classes for which I was responsible. At the high school, there was the third concert band, the top concert band, the jazz band and the orchestra. The middle school had the sixth- and eighth-grade bands. By the time I reached the final high school concert of the semester my final performance as a music educator and conductor I was more than ready to be done with teaching altogether. The four months that led up to this performance were extremely difficult, as I slowly counted down the days and hours until the end of my music career. I would be the first conductor for the performance, starting with the orchestra. While the lead-up to this day has been challenging, I still wanted to leave on a high mark. This had been the most meticulously planned of the programs on my part. It was December, so we were doing a largely Christmas-themed show. I ordered new music the first new pieces the ensemble had received in a while that fit around the skills of the group, whether that was highlighting the virtuosity of the lead violins or picking a jazz-style piece that allowed the percussion-oriented bass player to get a chance behind a drum set. In this three-piece performance, I let myself get lost in the music. I tried to emulate the great conductors and allowed the performance to flow through me, trusting the performers would demonstrate the acumen of our preparation. As the final notes of our last piece, a Dave Brubeck-esque version of Carol of the Bells, were played, I smiled, turned to the audience, and took a bow. I was really proud of the work my students had done. I identified the most with the orchestra. Despite only a semester of training on a stringed instrument, this was the group that I gave my most attention to. They had basically been neglected as an ensemble, so the effort I gave to them was probably the most focused interaction the group had received in a while. Perhaps I felt as out of place as they did, a lone class in a school system that didnt focus on orchestral performance, so I identified with their plight. For whatever reason, I had a sense of fulfillment training them. Even my cooperating teacher noticed, pointing out I needed to try and find the same excitement about teaching the other ensembles. After the orchestra, there was one more ensemble for me to conduct, I did do something else I rarely did: I addressed the audience. I said my public goodbye to the students and thanked their parents for giving me the chance to men-

tor their sons and daughters. I never told anyone at the school that I would be abandoning music education at the end of the term. I didnt want them to think they were responsible for that decision. By the next fall, I had abandoned music completely as a career. In my search for a new path, I was idling in Bloomington for the spring and summer of 2009. I applied to go back to Ball State, a return to the new home where I felt comfortable, this time moving to the Department of Journalism, which surprisingly welcomed me with open arms, giving me a chance when they really didnt have to. * * *

No matter where I stepped, there was mud. As the rain continued to pour from the sky, were sloshing through the recently plowed field with our laptops, cameras, and recorders. We tried to avoid the largest puddles as we looked for shelter for our equipment and ourselves. All the meanwhile, Brad King the professor to whom I was assigned for my graduate studies was barking orders, sending us back out into the near monsoon to find stories. Working on a build site for Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, which had turned into the worlds largest mud pit thanks to inches and inches of rain during the early part of the seven-day build, was going to be my baptism by fire. It was also my first chance to prove myself to Brad. He had been asked to take the lead on this project thanks to a connection between the building company and the universitys president. As his graduate assistant, his involvement meant I was tagging along as well. Despite his gruff demeanor, having Brad there was better than the alternative. He provided quite the safety net, coordinating the workflow. My primary responsibilities were updating the website, creating multimedia components such as a map of all the businesses who had donated supplies, and sending out other people to find stories and write them. My role largely kept me behind a computer screen, where I could be comfortable despite the inclement conditions. That comfort was stripped away as the week went on. Brad returned to the university, leaving me to run things from the site. My volunteer media group, which had numbered more than a dozen early in the week, trickled down to a small core of five or six as other requirements class, homework, sleep took precedent. I didnt have the bodies to throw at situations as they came up. I would have to start telling the stories. I would have to suck up my fear of

talking to people. And I did. I met people and tried to get to know them, to get some understanding of why they would be willing to give to a family that many of them had never met. In particular, I remember meeting Monty. He was one of the hundreds of volunteers who showed up after the rain had fallen. A rural man with a bald head and thick mustache, he was a shining example of a community who came together to do something wonderful for one family. No one had to be there, yet I was constantly amazed by the number of people who wanted to give just because they thought it was the right thing to do. The rain had turned the entire work site into a muddy mess. While that caused untold horrors to the builders and their effort to put up a house in less than a week, the staging area for the build, a soybean field located directly across the street, was hardly passable either. I had to throw away a relatively new pair of tennis shoes and a few pairs of jeans at the end of the week. But thanks to people like Monty, tons of straw was donated to the site and laid out. It made walking from tent to tent a little more bearable. Getting to tell that story of a man who was so willing to find ways to help in any way possible was one of my favorite parts of the experience. I was able to pull back the curtain and help show the people who would otherwise have gone unmentioned during the airing of the episode. They were the people who made the build possible, and I had the pleasure of getting to know a few of them. I realized two things from working in the mud. I discovered the joy that could be had in telling stories and I knew that it was an experience I wouldnt get hiding behind a computer. For the first time since I left for Ball State four years earlier, it felt like things may be all right. * * *

I was at home by myself on a Friday night in December 2009 when the phone rang. I have a bad habit of not answering my cell phone if I dont know who is calling, preferring to let the voice mail act as my secretary. But tonight I picked it up. On the other end was Charlyne Berens, a professor at the University of Nebraska. She was calling on behalf of the Dow Jones News Fund to ask if I would be interested in being an intern at ESPN.com. I was stunned. The Dow Jones News Fund organizes a massive copy editing internship every summer. Eligibility is based on a test taken in early October. I had joined the copy desk at the student newspaper on my first day of graduate school, but I had been doing that for less than two months when I took the

test. My application for the entire internship program was basically on a lark. I never thought I would actually qualify. I tried to play it cool, but I devolved into a bumbling idiot for the rest of the conversation, stammering through answers about my experience up to this point, which was minimal, and expressing why I was qualified for the position, which I didnt think I was. Somehow I got through it and let her know that, yes, I would like to work for ESPN. Moving to Connecticut, even for the summer, was going to be a culture shock. I would be far away from home and would know one other person when I arrived in the state. Amy was a fellow copy editor at ESPN, who I met at a convention just a couple of months prior to my internship. Otherwise, it was a state of unknowns. For me, life is much better with structure. I dont rigidly plan out each day, but I function much better with some understanding of how things work. After a 30-minute drive from my apartment in Hartford, Connecticut, to Bristol, where ESPNs headquarters are located, I met with one of my bosses, David, and took a tour of the campus. Once the internship officially began, a pattern developed somewhat innocuously. I would go to work, spend my day working on ESPNs website, then make the half-hour drive home. I would go up into my room and shut myself in. I would spend my evenings watching television and movies while they interacted. I was too afraid to introduce myself. A lifetime of uncertainty and poor social experiences had manifested itself in this summer internship. Out of a pool of nearly 75, I had managed to make only a single friend, another lost individual who hadnt managed to fit in. But even she moved on, lured by the power of the majority to spend time with the group. I was alone again. Most nights, I sat in my room after making dinner and tried to casually look out the window at the crowd. I didnt want it to appear as if I were staring. I longed to find the energy to get to know these people, and as the summer ticked away, I knew I was running out of time. The drive from my apartment to the ESPN headquarters took 25 minutes in the morning. As someone who hates getting up in the morning, that precision is important. Adding it to the other morning tasks showering (15 minutes), getting dressed (five minutes), and grabbing breakfast (10 minutes) lets me know exactly when I had to get out of bed. Driving back was more of a crapshoot. Construction on the interstate connecting work and home tended to start right as I was getting off work around 7 p.m. If I was unlucky, it meant sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic for an extra

half-hour as I made my way toward home at a snails pace. That extra time in the car was often a chance to decompress from the day of work. I would try to remember what had happened that day, what I planned to do with my upcoming days off. But as June turned into July and the end of the internship approached in the first week of August, my mind would turn to those wasted nights I was spending in my bedroom. I told myself that I needed to meet people, to escape the protection I had built around me. * * *

Meeting celebrities and other high-profile people was a daily occurrence at ESPN. You were never quite sure who was going to be walking around the campus or who might take a tour that passed by your desk. But at the end of the internship, just a couple of weeks before we were finished, the H.R. representatives were taking us to meet George Bodenheimer, the president of ESPN, at the Good Morning America studios in New York City. During the meeting, an intern-produced video documenting the summer was shown. Not surprisingly, I made no appearance in said video, since no one knew who I was. After the meeting, we were to navigate through Times Square to the nearby Dave and Busters for lunch. The studio was on the corner of 44th St. and Seventh Ave.; the restaurant was on 42nd between Seventh and Eighth. I didnt have anyone to walk with, so I started the trek on my own. Where I should have made a left, I turned right. It took me a couple of blocks to realize that the streets were increasing in number rather than decreasing. I had made it to 47th and Seventh and was half-lost in one of the biggest cities in the world. Quick backtracking got me back to the studio and on to the restaurant. But I was late. The 75 or so of us were crammed into a room that usually seating 50. This time, there was no corner to hide in and eat my lunch by myself. Hey, sit here. Katelin, one of the interns in post-production, had called me over to an empty seat. Grateful for the invitation, I made my way to the table and sat down. Looking around at the faces at the table, I realized how many I actually already knew, such as Megan, who was a local that I ate lunch with in the cafeteria a few times. Even scanning the room, I discovered that I had interacted with most of these people at least once. For the second time in less than an hour, I realized how foolish I had been. For the entire summer, I had been looking for some sort of invitation to be part of the club, when I had already been accepted. These friendships didnt need

a big moment where we acknowledged the relationship. We were all in this together. I had been so afraid of not making friends and/or losing friends that I had cost myself the chance to spend time with these people. I had been doing it all my life, though. Fear had overtaken me, but I would try to stop it from happening anymore. For the rest of that day, I enjoyed dinner with people, laughing at jokes, getting to live like a kid in the game room as we all amassed thousands of tickets to spend on the random trinkets offered at an arcade. Even riding back on the bus from New York City to Bristol, I was more engaged. I had a great conversation with Adam and Alex, two of my roommates for the summer, along with Joe, one of the coordinators. There didnt have to be a concern. I belonged just by joining in.

or the final 10 days of the internship, I was in my room only for sleeping and getting ready in the morning. My self-imposed exile had ended, and I started joining the rest of the interns regularly for meals at the ESPN campus and excursions around downtown Hartford. People starting leaving Connecticut on Wednesday of the final week of the internship, so Tuesday was our last hoorah in the city, a chance to celebrate the bond created during the previous 10 weeks. There was no question that I was invited to the dinner; I had become one of the group. Thirty of us invaded a high-class restaurant, taking over an entire section of the establishment. Over drinks and dinner, we reminisced and talked about where we would be going after ESPN, what it was like at our schools, and what we wanted to do after graduation. I really enjoyed reading your blog this summer, Rhett, Will, an intern from Cornell University, said. I was taken aback. I had been documenting the events of the summer through a writing regiment that required me to write every day another creation of Brad King. Will went to tout the blog to other people at the table. It was nice to know that people cared enough to read my words when I had been so awful at getting to know them. After dinner, we headed to the bar. It was my second trip there that week, as it was the regular establishment for the interns. The inside contained plenty of wood paneling. It felt as if the inside of a ski lodge had been renovated into a bar, with a large dance floor in the middle. While the first visit had been kara-

oke night, a DJ was running the evening this night. Through the night, I shared shots and stories with Blake, danced with the group, posed for plenty of pictures, and saw one of the more absurd moments of the entire summer. The bar had set up a money grab in a windy booth to boost sales on what was likely a typically slow Tuesday night. While the regular way to earn a trip to the booth and some quick cash was through a raffle, the DJ had decided to hold a booty-shaking contest. This was normally a femaleonly competition, but when the audience controlled who advanced and more than half of that crowd was ESPN interns lets just say we were the superpower of the voting bloc. Fortunately, we had some rather outgoing men willing to compete, including Justin. He was from the University of South Carolina and apparently had no shame in shaking his way to victory. And we were more than willing to make sure that happens. Loud chants of Justin! Justin! rang through the bar after each song. Eventually, the contest came down to two ESPN interns: Justin and Katie from the University of Texas. While everyone liked Katie, she never had a chance, much to the dismay of the DJ. I dont know what it says about you guys that a dude just won the bootyshaking contest, he announced to the laughs and cheers of the ESPN interns. These were the silly moments I had missed during the summer, but I was grateful to take part in the shenanigans for this night. I came to regret the time I hadnt spent with them during the first part of the internship. I had let fear control me and keep me from getting to know a crowd I had a natural connection to. I realized that throughout my life, this uncertainly and fear of being rejected had dictated my life choices. My fear of losing a relationship kept me from leaving Bloomington when I needed to get out of my hometown. My worry about letting down professors and friends was my sole holdback from changing from music originally. Being afraid had taken over my life. Its completely illogical. I dont want to shut myself off from the world. Not everyone has to like me either. I was too worried about the approval of others, when I realize now that I dont have to be concerned with what other people think of me all the time. Ill never be the life of the party, the center of attention. At least, Id rather not be. But I would like to be included, and the only way to do that is to make myself available. * * *

I would leave Connecticut and return to Indiana with a new understanding of how I work and what I wanted to do with my life. If I couldnt get back to this dream job, Id find another path for myself. Returning to Ball State for one more year included working at the student newspaper, the Daily News. Despite having just a year of experience working at the paper, I found myself as one of the primary leaders. This required me to take on a duty I had sought to avoid for so long interacting with people on a near-constant basis. There was a story about a band that was set to run in the next days paper. At the last moment, I realized that one of the quotes was the band member reciting the plot to an obscure 90s movie, Empire Records. It was one of those random catches that happened because I had seen the movie years before. Going up to the features editor, I explained what the band had tried to pull and that we needed to take the story out of the paper. Yet she said no, sending me into a rage. I resorted to yelling to get my point across, but she wouldnt budge and neither would the editor-in-chief. The offending quote was removed, but the story stayed. While I had lost the battle, I realized that I wasnt afraid to express myself to another person. Instead, for \probably the first time in my life, I had to understand how to tone down my beliefs. I also came to rely on the teaching degree I had earned years before. The fear that plagued me in front of middle and high school students was gone. I enjoyed getting to instruct fellow students. I wasnt always effective, but I did the best I could to teach before I left, making that education degree no longer feel like a waste. I worked on finding a middle ground. After years of holding back, I didnt want to swing to the opposite side and turn into a raving maniac. I wanted to take things in stride, looking for the best solution possible that would appease everyone involved. When I started to feel my blood boil, I would take a moment to step back, breathe and then reevaluate the situation and how I could improve it. It felt good to finally have a sense of control over what I was doing. It had taken more than seven years, but I finally found a comfort with where I was and what I was doing. While I will leave my safety net of the university soon, I no longer feel the need for its protection. I may fall along the away, but I now have an understanding of how to pick myself up. The fear that plagued me for so long finally went away.

If I Leave Here Tomorrow by The Invictus Writers is licensed under a Creative Commons-Atrribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.thedudeman.net. Photo by Tanakawho, available through the Creative Commons License. See the original picture: http://www.flickr.com/photos/28481088@N00/2392511288/.

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Division Teacher Induction Program: "The Quality of An Education System Cannot Exceed The Quality of Its TeachersДокумент43 страницыDivision Teacher Induction Program: "The Quality of An Education System Cannot Exceed The Quality of Its TeachersJBSUОценок пока нет

- Lessons From The ClassroomДокумент2 страницыLessons From The Classroomina0% (1)

- Module 5Документ2 страницыModule 5prof_kt0% (1)

- Ds Resume Updated Aug 17 21Документ4 страницыDs Resume Updated Aug 17 21api-538512056Оценок пока нет

- Allied School: Maths Important Long Questions For 9th Class With Book ReferenceДокумент2 страницыAllied School: Maths Important Long Questions For 9th Class With Book ReferenceAbdul QadirОценок пока нет

- Ped 3138 Place Story - Gina Morphy-3Документ6 страницPed 3138 Place Story - Gina Morphy-3api-252825989Оценок пока нет

- UtahcorestandardsДокумент80 страницUtahcorestandardsapi-448841552Оценок пока нет

- Dr. W. Edwards Deming - The Father of The Quality EvolutionДокумент3 страницыDr. W. Edwards Deming - The Father of The Quality EvolutionVbaluyoОценок пока нет

- Materi Micro TeachingДокумент9 страницMateri Micro TeachingannisaoktavianiОценок пока нет

- Substitution Table ExplainedДокумент7 страницSubstitution Table ExplainedaimarОценок пока нет

- Parag Mahajani Corporate Profile 2013Документ3 страницыParag Mahajani Corporate Profile 2013Parag MahajaniОценок пока нет

- Treaty 7 Lesson PlanДокумент2 страницыTreaty 7 Lesson Planapi-385667945Оценок пока нет

- Tracer Survey of Agriculture GraduatesДокумент12 страницTracer Survey of Agriculture GraduateskitkatiktakОценок пока нет

- PublicationДокумент2 страницыPublicationVikki AmorioОценок пока нет

- RV 35 MMДокумент3 страницыRV 35 MMkazi wahexОценок пока нет

- Revised Lanl Cover LetterДокумент2 страницыRevised Lanl Cover Letterapi-317266054Оценок пока нет

- Jewel in The CityДокумент21 страницаJewel in The CityDr. Sarah O'Hana100% (1)

- Edu 543 Pe FieldworkДокумент11 страницEdu 543 Pe Fieldworkapi-300022177Оценок пока нет

- The Impact of Online Learning in The Mental Health of ABM StudentsДокумент3 страницыThe Impact of Online Learning in The Mental Health of ABM StudentsJenny Rose Libo-on100% (3)

- Lesson Plan: Subject: MET 410 B Professor: Marisol Cortez Written By: Gustavo Rojas, Roxana VillcaДокумент2 страницыLesson Plan: Subject: MET 410 B Professor: Marisol Cortez Written By: Gustavo Rojas, Roxana VillcaNolan RedzОценок пока нет

- Gradation As On 01 03 2022 06374aee34897b3 97522778Документ3 339 страницGradation As On 01 03 2022 06374aee34897b3 97522778Naina GuptaОценок пока нет

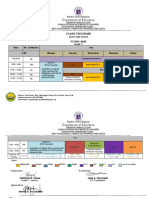

- Class Program Grade 7-10Документ9 страницClass Program Grade 7-10jake felicianoОценок пока нет

- Standardized Testing Chapter 4 BrownДокумент38 страницStandardized Testing Chapter 4 BrownYamith J. Fandiño100% (3)

- AAAP Directory-2013Документ60 страницAAAP Directory-2013Manoj KumarОценок пока нет

- Lect. 6.2 Caribbean EducationДокумент8 страницLect. 6.2 Caribbean EducationToriОценок пока нет

- As 4Документ8 страницAs 4jessie jacolОценок пока нет

- Culture UAEДокумент12 страницCulture UAEanant_jain88114Оценок пока нет

- Apprenticeship+ AdevertisementДокумент9 страницApprenticeship+ Adevertisementaltaf0987ssОценок пока нет

- East Centralite 1916-1919Документ180 страницEast Centralite 1916-1919Katherine SleykoОценок пока нет

- Everett Rogers Diffusion of Innovations Theory PDFДокумент4 страницыEverett Rogers Diffusion of Innovations Theory PDFa lОценок пока нет