Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Inventory Balance Sheet: Inventory Valuation For Investors: FIFO and Lifo

Загружено:

ranotabbsИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Inventory Balance Sheet: Inventory Valuation For Investors: FIFO and Lifo

Загружено:

ranotabbsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Are you one of those investors who doesn't look at how a company accounts for its inventory?

For many companies, inventory represents a large (if not the largest) portion of assets and, as such, makes up an important part of the balance sheet. It is, therefore, crucial for investors who are analyzing stocks to understand how inventory is valued. (In times of economic distress and reduction in consumer spending, businesses always look for ways to increase profits. find out more, in Inventory Valuation For Investors: FIFO And LIFO.) What is Inventory? Inventory is defined as assets that are intended for sale, are in process of being produced for sale or are to be used in producing goods. The following equation expresses how a company's inventory is determined: Beginning Inventory + Net Purchases - Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) = Ending Inventory In other words, you take what the company has in the beginning, add what it has purchased, subtract what's been sold, and the result is what remains. How do We Value Inventory? The accounting method that a company decides to use to determine the costs of inventory can directly impact the balance sheet, income statement and statement of cash flow. There are three inventory-costing methods that are widely used by both public and private companies: First-In, First-Out (FIFO) This method assumes that the first unit making its way into inventory is the first sold. For example, let's say that a bakery produces 200 loaves of bread on Monday at a cost of $1 each, and 200 more on Tuesday at $1.25 each. FIFO states that if the bakery sold 200 loaves on Wednesday, the COGS is $1 per loaf (recorded on the income statement) because that was the cost of each of the first loaves in inventory. The $1.25 loaves would be allocated to ending inventory (appears on the balance sheet).

, (LIFO) This method assumes that the last unit making its way into inventory is sold first. The older inventory, therefore, is left over at the end of the accounting period. For the 200 loaves sold on Wednesday, the same bakery would assign $1.25 per loaf to COGS, while the remaining $1 loaves would be used to calculate the value of inventory at the end of the period.

This method is quite straightforward; it takes the weighted average of all units available for sale during the accounting period and then uses that average cost to determine the value of COGS and ending inventory. In our bakery example, the average cost for inventory would be $1.125 per unit, calculated as [(200 x $1) + (200 x $1.25)]/400. An important point in the examples above is that COGS appears on the income statement, while ending inventory appears on the balance sheet under current assets. (For more insight, see Reading The Balance Sheet.) Why is Inventory Important? If inflation were nonexistent, then all three of the inventory valuation methods would produce the exact same results. When prices are stable, our bakery would be able to produce all of its loafs of bread at $1, and FIFO, LIFO and average cost would give us a cost of $1 per loaf. Unfortunately, the world is more complicated. Over the long term, prices tend to rise, which means the choice of accounting method can dramatically affect valuation ratios. If prices are rising, each of the accounting methods produce the following results: FIFO gives us a better indication of the value of ending inventory (on the balance sheet), but it also increases net income because inventory that might be several years old is used to value the cost of goods sold. Increasing net income sounds good, but remember that it also has the potential to increase the amount of taxes that a company must pay. LIFO isn't a good indicator of ending inventory value because the leftover inventory might be extremely old and, perhaps, obsolete. This results in a valuation that is much lower than today's prices. LIFO results in lower net income because cost of goods sold is higher. Average cost produces results that fall somewhere between FIFO and LIFO.

(Note: if prices are decreasing, then the complete opposite of the above is true.) One thing to keep in mind is that companies are prevented from getting the best of both worlds. If a company uses LIFO valuation when it files taxes, which results in lower taxes when prices are increasing, it then must also use LIFO when it reports financial results to shareholders. This lowers net income and, ultimately, earnings per share. (Cashvalue has always provided consumers with a tax-free avenue of growth within the policy that could be accessed at any time, for any reason. Find out more, in Insurance: Avoiding The Modified Endowment Contract Trap.) Example Let's examine the inventory of Cory's Tequila Co. (CTC) to see how the different inventory valuation methods can affect the financial analysis of a company.

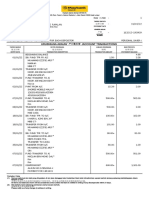

Monthly Inventory Purchases* Month January February March Total Beginning Inventory = 1,000 units purchased at $8 each (a total of 4,000 units) Units Purchased Cost/ea 1,000 1,000 1,000 3,000 $10 $12 $15 Total Value $10,000 $12,000 $15,000

Income Statement (simplified): JanuaryMarch* Item Sales = 3,000 units @ $20 each Beginning Inventory Purchases Ending Inventory (appears on B/S) *See calculation below COGS Expenses Net Income LIFO $60,000 8,000 37,000 8,000 $37,000 10,000 $13,000 FIFO $60,000 8,000 37,000 15,000 $30,000 10,000 $20,000 Average $60,000 8,000 37,000 11,250 $33,750 10,000 $16,250

*Note: All calculations assume that there are 1,000 units left for ending inventory: (4,000 units - 3,000 units sold = 1,000 units left) What we are doing here is figuring out the ending inventory, the results of which depend

on the accounting method, in order to find out what COGS is. All we've done is rearrange the above equation into the following: Beginning Inventory + Net Purchases - Ending Inventory = Cost of Goods Sold

LIFO Ending Inventory Cost = Remember that the last units in are sold first; therefore, we leave the oldest units for ending inventory.

1,000 units X $8 each = $8,000

FIFO Ending Inventory Cost = Remember that the first units in (the oldest ones) are sold first; therefore, we leave the newest units for ending inventory.

1,000 units X $15 each = $15,000

Average Cost Ending Inventory =

[(1,000 x 8) + (1,000 x 10) + (1,000 x 12) + (1,000 x 15)]/4000 units = $11.25 per unit 1,000 units X $11.25 each = $11,250

Remember that we take a weighted average of all the units in inventory. Using the information above, we can calculate various performance and leverage ratios. Let's assume the following: Assets (not including inventory) Current assets (not including inventory) Current liabilities $150,000 $100,000 $40,000

Total liabilities

$50,000

Each inventory valuation method causes the various ratios to produce significantly different results (excluding the effects of income taxes): Ratio Debt-to-Asset Working Capital Inventory Turnover Gross Profit Margin LIFO 0.32 2.7 7.5 38% FIFO 0.30 2.88 4.0 50% Average Cost 0.31 2.78 5.3 44%

To learn more about each ratio listed above, see the Ratio Analysis Tutorial. As you can see from the ratio results, inventory analysis can have a big effect on the bottom line. Unfortunately, a company probably won't publish its entire inventory situation in its financial statements. Companies are required, however, to state in the notes to financial statements what inventory system they use. By learning how these differences work, you will be better able to compare companies within the same industry. Conclusion Many companies will also state that they use the "lower of cost or market." This means that if inventory values were to plummet, their valuations would represent the market value (or replacement cost) instead of FIFO, LIFO or average cost. Understanding inventory calculation might seem overwhelming, but it's something you need to be aware of. Next time you're valuing a company, check out its inventory; it might reveal more than you thought.

Вам также может понравиться

- Understanding Financial Statements (Review and Analysis of Straub's Book)От EverandUnderstanding Financial Statements (Review and Analysis of Straub's Book)Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (5)

- Afar04 Business Combinations Mergers ReviewersДокумент17 страницAfar04 Business Combinations Mergers ReviewersPam G.100% (5)

- Determining The Monetary Amount of Inventory at Any Given Point in TimeДокумент44 страницыDetermining The Monetary Amount of Inventory at Any Given Point in TimeParth R. ShahОценок пока нет

- CPAR87 Final PB - AFARДокумент15 страницCPAR87 Final PB - AFARLJ AggabaoОценок пока нет

- Options Open Interest AnalysisДокумент27 страницOptions Open Interest Analysisgkrishnan59Оценок пока нет

- Expert Advisor and Forex Trading Strategies: Take Your Expert Advisor and Forex Trading To The Next LevelОт EverandExpert Advisor and Forex Trading Strategies: Take Your Expert Advisor and Forex Trading To The Next LevelРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Valuation of Inventories A Cost-Basis ApproachДокумент46 страницValuation of Inventories A Cost-Basis ApproachIrwan JanuarОценок пока нет

- IAS 36 Impairment of AssetsДокумент22 страницыIAS 36 Impairment of AssetsZeeshan Mahmood100% (1)

- Inventory Accounting and ValuationДокумент4 страницыInventory Accounting and ValuationFathi Salem Mohammed Abdullah100% (1)

- Accounting For InventoriesДокумент9 страницAccounting For InventoriesPrince AngelОценок пока нет

- Lifo FifoДокумент3 страницыLifo FifoVenus BhattiОценок пока нет

- LIFO Vs FIFO Vs FEFO ExplainedДокумент8 страницLIFO Vs FIFO Vs FEFO ExplainedFayssal El haddad100% (1)

- What Is Last In, First Out (LIFO) ?Документ2 страницыWhat Is Last In, First Out (LIFO) ?Niño Rey LopezОценок пока нет

- Inventory Accounting Methods: Specific Identification MethodДокумент9 страницInventory Accounting Methods: Specific Identification MethodVidhya ChuriОценок пока нет

- Inventory ValuationДокумент10 страницInventory ValuationKritika RajОценок пока нет

- How Firms Value InventoryДокумент6 страницHow Firms Value InventoryShreya ChowdharyОценок пока нет

- Understand Inventory Costing Methods Like LIFO and FIFOДокумент7 страницUnderstand Inventory Costing Methods Like LIFO and FIFOgetasewОценок пока нет

- Inventory Valuation GuideДокумент43 страницыInventory Valuation GuideQuyen Thanh NguyenОценок пока нет

- DQ 1 - Due by Thursday 1/6/11: Week One (January 4, 2011 - January 10, 2011)Документ4 страницыDQ 1 - Due by Thursday 1/6/11: Week One (January 4, 2011 - January 10, 2011)starburst56Оценок пока нет

- Transcript For Lecture Video 1Документ5 страницTranscript For Lecture Video 1StaygoldОценок пока нет

- COMPARATIVE STUDY ON INVENTORY COSTING METHODS (FIFO, LIFO, AVERAGEДокумент5 страницCOMPARATIVE STUDY ON INVENTORY COSTING METHODS (FIFO, LIFO, AVERAGEAziz Bin AnwarОценок пока нет

- Chapter 08 Solution of Fundamental of Financial Accouting by EDMONDS (4th Edition)Документ133 страницыChapter 08 Solution of Fundamental of Financial Accouting by EDMONDS (4th Edition)Awais Azeemi100% (2)

- Taller Seis Acco 111Документ44 страницыTaller Seis Acco 111api-274120622Оценок пока нет

- Week 3 Chapter 5 - Inventories and Cost of Sales ACC 201 - National UniversityДокумент135 страницWeek 3 Chapter 5 - Inventories and Cost of Sales ACC 201 - National Universitymusic niОценок пока нет

- 8 (A) - Master BudgetДокумент4 страницы8 (A) - Master Budgetshan_1299Оценок пока нет

- Inventory Valuation MethodsДокумент2 страницыInventory Valuation MethodsAmin FarahiОценок пока нет

- Inventory Costing Methods: Reported By: Joanne OlivaДокумент19 страницInventory Costing Methods: Reported By: Joanne OlivaTon Nd QtanneОценок пока нет

- Lipo FifoДокумент4 страницыLipo FifoJAS 0313Оценок пока нет

- Methods InventoryДокумент12 страницMethods InventoryJocelyn LimaОценок пока нет

- 2016030f4150712chap 8 AssignmentДокумент3 страницы2016030f4150712chap 8 AssignmentReynante Dap-ogОценок пока нет

- About Inventory TopicДокумент18 страницAbout Inventory TopicXin YiiОценок пока нет

- Accounting For InventoryДокумент10 страницAccounting For InventoryHafidzi DerahmanОценок пока нет

- LIFO Method - AccountingToolsДокумент2 страницыLIFO Method - AccountingToolsMd Rakibul HasanОценок пока нет

- Comparing Different Inventory Valuation Methods: Fifo, Lifo, and WacДокумент34 страницыComparing Different Inventory Valuation Methods: Fifo, Lifo, and WacMarzelie Quanz Maricel Quintilla-QuinesОценок пока нет

- Audit Unit IIIДокумент67 страницAudit Unit IIIAbhishek JhaОценок пока нет

- Financial Accounting-Unit-4-SYMBДокумент35 страницFinancial Accounting-Unit-4-SYMBGarima KwatraОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8: Valuation of Inventories: A Cost Basis ApproachДокумент28 страницChapter 8: Valuation of Inventories: A Cost Basis ApproachChris WongОценок пока нет

- Kelompok 6 Chapter 6Документ11 страницKelompok 6 Chapter 6leoni pannaОценок пока нет

- Inventory Costing MethodsДокумент4 страницыInventory Costing MethodsjosiahОценок пока нет

- Fifo & LIFO: Abhay Tyagi Saket Abhinav TyagiДокумент15 страницFifo & LIFO: Abhay Tyagi Saket Abhinav Tyagiabhaytytyagi123Оценок пока нет

- Inventories and Cost of Goods SoldДокумент7 страницInventories and Cost of Goods Soldpri_dulkar4679100% (1)

- Intermediate I Chapter 8Документ45 страницIntermediate I Chapter 8Aarti JОценок пока нет

- FIFO Inventory Method GuideДокумент6 страницFIFO Inventory Method GuideVanessa Plata Jumao-asОценок пока нет

- Retail Math 101 - The Formulas You Need To Know: Beginning Inventory + Purchases - Ending Inventory CogsДокумент9 страницRetail Math 101 - The Formulas You Need To Know: Beginning Inventory + Purchases - Ending Inventory CogsPULKIT BHATIAОценок пока нет

- Inventory Practice ProblemsДокумент14 страницInventory Practice ProblemsmikeОценок пока нет

- Accounting For Manager DДокумент315 страницAccounting For Manager DPRASANJIT MISHRAОценок пока нет

- 2010-06-23 203304 Financialaccounting 2Документ6 страниц2010-06-23 203304 Financialaccounting 2pi!Оценок пока нет

- Fifo Vs LifoДокумент3 страницыFifo Vs LifoMrityunjayChauhanОценок пока нет

- LIFO or FIFO? That's The Question Case Summary and ISSUESДокумент4 страницыLIFO or FIFO? That's The Question Case Summary and ISSUESBinodini SenОценок пока нет

- Accounting for Inventories Under FIFO, LIFO, Average CostДокумент2 страницыAccounting for Inventories Under FIFO, LIFO, Average CostKev0% (1)

- What Is Asset V-WPS OfficeДокумент15 страницWhat Is Asset V-WPS OfficeGift EdigbeОценок пока нет

- FIFO and LIFOДокумент9 страницFIFO and LIFOM ASHIBUR RAHMANОценок пока нет

- Chapter 7 Inventory Problem Solutions Assessing Your Recall 7.1Документ32 страницыChapter 7 Inventory Problem Solutions Assessing Your Recall 7.1Judith DelRosario De RoxasОценок пока нет

- Fatimatuz Zahro - Ex 2 - ch06Документ2 страницыFatimatuz Zahro - Ex 2 - ch06Fatimatuz ZahroОценок пока нет

- Valuation of Inventories: A Cost-Basis ApproachДокумент36 страницValuation of Inventories: A Cost-Basis ApproachjulsОценок пока нет

- What is Break Even AnalysisДокумент5 страницWhat is Break Even AnalysisElaine MagbuhatОценок пока нет

- Inventories Valuation A Cost Basis ApproachДокумент19 страницInventories Valuation A Cost Basis Approachabshir haybeОценок пока нет

- Text5-Accounting For Materials-Student ResourceДокумент10 страницText5-Accounting For Materials-Student Resourcekinai williamОценок пока нет

- Inventory and Cost of Goods Sold Quiz - Accounting CoachДокумент3 страницыInventory and Cost of Goods Sold Quiz - Accounting CoachSudip BhattacharyaОценок пока нет

- One of The Largest Current Assets InventoryДокумент15 страницOne of The Largest Current Assets InventorySaadat ShaikhОценок пока нет

- The Last-In-First-Out Method (LIFO)Документ6 страницThe Last-In-First-Out Method (LIFO)usman159159Оценок пока нет

- Reporting and Interpreting Cost of Goods Sold and InventoryДокумент40 страницReporting and Interpreting Cost of Goods Sold and InventoryPedroОценок пока нет

- Guide to Japan-born Inventory and Accounts Receivable Freshness Control for managersОт EverandGuide to Japan-born Inventory and Accounts Receivable Freshness Control for managersОценок пока нет

- Practice QuestionsДокумент4 страницыPractice QuestionsDimple PandeyОценок пока нет

- Assignments-Mba Sem-Ii: Subject Code: MB0029Документ28 страницAssignments-Mba Sem-Ii: Subject Code: MB0029Mithesh KumarОценок пока нет

- Graham & Harvey 2001 The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance Evidence From The FieldДокумент53 страницыGraham & Harvey 2001 The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance Evidence From The Fielder4sall100% (1)

- List of Specified Income From Designated InvestmentsДокумент3 страницыList of Specified Income From Designated InvestmentsOng Yong Xin, SeanneОценок пока нет

- Dictionary of Consulting JargonsДокумент27 страницDictionary of Consulting JargonsAkash TripathiОценок пока нет

- The Securities Law of The People's Republic of China: An OverviewДокумент24 страницыThe Securities Law of The People's Republic of China: An OverviewlauraОценок пока нет

- 2C00445Документ41 страница2C00445VijayОценок пока нет

- Micro-Econ Signature Assignment - Gavin WestДокумент4 страницыMicro-Econ Signature Assignment - Gavin Westapi-531246385Оценок пока нет

- PLEASE READ OUR FAQ FIRST - Http://bit - Ly/btcguidefaq: Best Trading Course PricelistДокумент1 страницаPLEASE READ OUR FAQ FIRST - Http://bit - Ly/btcguidefaq: Best Trading Course PricelistBillionairekaОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Corporate Finance 5th Edition Frino Test BankДокумент17 страницIntroduction To Corporate Finance 5th Edition Frino Test Bankbradleygillespieditcebswrf100% (20)

- Project Finance Tools and TechniquesДокумент104 страницыProject Finance Tools and Techniqueskapenrem2003Оценок пока нет

- Internship Report Sindh BankДокумент34 страницыInternship Report Sindh BankAl RafioОценок пока нет

- DCF Model of Bharti Airtel: AssumptionsДокумент4 страницыDCF Model of Bharti Airtel: AssumptionsHARSHIL RATHIОценок пока нет

- Evaluating System Efficiency: Money ManagementДокумент4 страницыEvaluating System Efficiency: Money ManagementPinky BhagwatОценок пока нет

- My Subscriptions Courses ACC410-Advanced Accounting Chapter 2 HomeworkДокумент29 страницMy Subscriptions Courses ACC410-Advanced Accounting Chapter 2 Homeworksuruth242Оценок пока нет

- Financial Management Guide: Investment, Financing and Dividend DecisionsДокумент34 страницыFinancial Management Guide: Investment, Financing and Dividend DecisionsLatha VarugheseОценок пока нет

- Dividends Company LawДокумент18 страницDividends Company LawKhizar Jamal SiddiquiОценок пока нет

- Depreciation MethodsДокумент21 страницаDepreciation MethodsPawan PoynauthОценок пока нет

- Market: Oncept of Market and Major Markets in An EconomyДокумент2 страницыMarket: Oncept of Market and Major Markets in An EconomyIheti SamОценок пока нет

- Role of Merchant Bankers in Capital MarketsДокумент23 страницыRole of Merchant Bankers in Capital MarketschandranilОценок пока нет

- TB - Chapter05 - RISK AND RATES OF RETURNДокумент86 страницTB - Chapter05 - RISK AND RATES OF RETURNĐặng Văn TânОценок пока нет

- Managerial Economics Questions: ProductionДокумент4 страницыManagerial Economics Questions: ProductionTrang NgôОценок пока нет

- Financial Markets and Institutions: EthiopianДокумент35 страницFinancial Markets and Institutions: Ethiopianyebegashet88% (24)

- Determinants of Dividends Policy and Dividend Policy of Companies Trend and Ratio AnalysisДокумент31 страницаDeterminants of Dividends Policy and Dividend Policy of Companies Trend and Ratio Analysissonal jainОценок пока нет

- Accounting for Business Combinations Midterm Exam ReviewДокумент4 страницыAccounting for Business Combinations Midterm Exam ReviewMica Ella San DiegoОценок пока нет

- Split 162013 190909 - 20220331Документ5 страницSplit 162013 190909 - 20220331NUR FASIHAH BINTIОценок пока нет