Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Broyhill Letter - Part Duex (Q2-11)

Загружено:

Broyhill Asset ManagementИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Broyhill Letter - Part Duex (Q2-11)

Загружено:

Broyhill Asset ManagementАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

S E C O N D Q U A RT E R 2 0 1 1

THE BROYHILL LETTER

Historical experience tends to support the proposition that a sufciently determined Fed can peg or cap Treasury bond prices and yields at other than the shortest maturities. The most striking episode of bond-price pegging occurred during the years before the Federal Reserve-Treasury Accord of 1951. Prior to that agreement, which freed the Fed from its responsibility to x yields on government debt, the Fed maintained a ceiling of 2-1/2 percent on long-term Treasury bonds for nearly a decade . . . The Fed was able to achieve these low interest rates despite a level of outstanding government debt (relative to GDP) signicantly greater than we have today, as well as ination rates substantially more variable . . . Interestingly, though, the Fed enforced the 2-1/2 percent ceiling on long-term bond yields for nearly a decade without ever holding a substantial share of longmaturity bonds outstanding. Ben Bernanke, Deation: Making Sure It Doesnt Happen Here (2002) The rare occasions of liquidity traps are very different from typical economic recessions. Consequently, they require a unique monetary policy response. Economic theory tells us that in such circumstances monetary policy should aim to lower the real, or ination-adjusted, rate of interest by temporarily allowing ination to rise above its long-run path . . . The higher ination would decrease the real interest rate, raising the opportunity cost of holding money. This would provide an incentive for banks and corporations to release funds for investment and in the process spur job creation. Chicago Fed President Charles Evans (2010)

Executive Summary

Policymakers have put all their eggs in a basket that has never been stress tested, hatched from a chicken that no one has seen for a century. Unconventional has become conventional, especially in terms of monetary policy. But current policy is unlikely to be as effective in supporting aggregate demand as economic theory would suggest. The transmission mechanism to the real economy is broken. In a Balance Sheet Recession, monetary policy is hopeless, so scal policy is required to ll the gap in private sector demand. Decit spending is harmful when it fails to enhance long term productivity or to produce a future stream of cash ows capable of servicing the increased debt load. But an intelligent scal response is one of the few weapons in our arsenal for dealing with a protracted downturn. Needless to say, Cash for Clunkers does not t our denition of intelligent. We need smart policies from strong leaders such as investment in infrastructure, incentives for research and development, a simplied and predictable tax policy, and heaven forbid someone actually address our long term entitlement liabilities! While consumers desire to pay down debt is positive for the long term health of the economy, the lack of new credit hampers the economys ability to recover through the normal post-recession cyclical channels. As such, government spending is required to articially support economic growth while the private sector rebuilds its balance sheet and is once again able to support healthy levels of credit creation. Fiscal policy is the only way to deal with a large output gap. Frontloaded Fiscal Austerity is counterproductive and would only serve as a deationary shock to aggregate demand - especially if the developed worlds economies pursue it at the same time (dont look now, but this is exactly the policy being jammed down Europes throat today). History warns that when governments stop stimulus too soon, recessionary forces reassert themselves. Poorly timed decit reductions can reduce GDP and prompt a drop in tax revenues, translating into bigger decits, more cuts, less taxes, etc. (i.e. Southern Europe). This is the type of self-reinforcing cycle policy makers have nightmares about. Unfortunately, maintaining scal stimulus for the entire duration of a Balance Sheet Recession is politically impossible. There are many, many years of deleveraging ahead of us.

Lower for Longer

We have long believed that the path of least resistance for interest rates is down, at least until the deleveraging process has run its course. In other words, demand for credit will remain muted until the private sector reduces its debt to more manageable levels. Fiscal decits are not crowding out private sector borrowing because the private sector doesnt want

S E C O N D Q U A RT E R 2 0 1 1

to borrow. Rather, scal decits are facilitating the private sectors desire to save more, deleveraging their balance sheets. The private sector in the developed world needs to get its nancial house in order. And the only way that can happen in the near term, without increasing the risk of a deationary depression, is for the governments of the developed world to run large decits. One gauge we are monitoring for progress is the Household Financial Obligations Ratio (FOR), a broad measure of debt payments relative to disposable personal income. While the FOR has fallen from its Q1-08 peak, a move towards its early 80s low would be more indicative of a secular low. Unfortunately, a big slug of the improvement in the ratio to date has come from government transfer payments, which have temporarily boosted disposal personal income. Excluding transfer payments, the FOR has declined by a fraction of the magnitude illustrated above and remains well above both its long term average and prior lows. Much lower levels are needed to provide a base to build upon. Understanding the mechanics of a Balance Sheet Recession is critical to understanding why large government debts can coexist with low interest rates. Put simply, the amount of money borrowed by the government to offset the contraction in private sector credit is by denition equivalent to the excess savings in the system. Yields on government debt are likely to stay Lower for Longer. The greatest irony in all of this hysteria is that those who are shrieking the loudest about the prospect for rising yields fail to understand why interest rates might rise in the current environment. Despite massive debt levels, private sector deleveraging, deation risks, etc., the only thing that got interest rates moving higher in the 1940s was an economic recovery! Budget decits have a meager 40% correlation to bond yields, while Fed policy and ination command 80% to 90% correlations with the treasury market. And the Fed has repeatedly told us they have no intention of raising rates for a long, long time. Interestingly, when Heli-Ben gave his What If speech in November 2002, he mentioned that in a 0% world, he would target long term rates to mitigate deation risks. He specically cited how the Fed established an explicit ceiling on the long bond yield of 2.5% in the decade to 1951. Interesting. Interest rates are best explained by the ebb and ow of economic data and have a positive correlation with LEIs which grows still stronger when ination pressures are subdued. Yields are falling because the outlook for growth is deteriorating. Bond yields surged in 2009 alongside rising LEIs and hopes of a sustainable recovery. Bond yields plummeted in the spring of 2010, as those hopes were shattered. Beyond the short term cyclical ow of economic data, interest rates should trend lower for the next few years as experience supports the view that recessions are deationary by nature. In the 11 recessions since 1950, CPI declined on average for roughly 29 months after the recession ended. Considering the structural differences inherent in an extended deleveraging process, wed expect a much more extended decline this time around.

2

S E C O N D Q U A RT E R 2 0 1 1

Size Matters

Given our massive debt bubble, even minor rises in interest rates create enormous difculties in debt service. The result is a global economy much more sensitive to changes in interest rates. Because debt burdens are a function of the rate of interest and the quantity of debt, when debt levels are high, smaller changes in interest rates have a larger impact on debt service burdens and on the economy. The choking point of rising rates on the economy has become lower and lower over time. In other words, greater and greater levels of debt act as larger and larger speed bumps for economic growth. Put simply, with an ever increasing weight of debt on our shoulders it takes successively smaller hiccups in yields, to break the economys back. In 1989, when rates rose to 9.5%, they popped the commercial real estate bubble and caused the S&L crisis. In 1999, the tech bubble burst as rates approached 6.5%. And in June of 2006, interest rates at 5.25% triggered a collapse of the residential property market and brought about the Great Recession. We believe the next choking point for the economy is likely to be signicantly lower than the previous ones, given the massive surge in public and private sector debt loads and the looming threat of debt deation.

Source: Bienville Capital Management

Deation, deleveraging, and risk-aversion will likely continue for longer than most expect. This toxic mix, combined with Bernankes desire to keep rates low, should result in progressively lower yields down the road and bodes very well for long term bonds. The average long term Treasury rate from 1870 is 4.3% while the average annual ination rate over this period is 2.1%. If ination goes to zero (or negative), then the long term bond yield should fall toward 2% (or lower). At current yields, we believe long term bonds offer an attractive hedge against continued deleveraging. After falling dramatically during the recession, nominal GDP ended the 30s where it started, so there was no growth for the entire period. Long term US Treasury rates dropped from 3.6% in 1929 to 1.9% in 1941 and the US stock market declined 62% over the entire period. In Japan, nominal GDP remained at for 20 years, even though debt as a percentage of GDP went from 50% to 200%. During this time, interest rates fell from 5.7% in 1989 to below 1% last year and the Nikkei was down over 77% over this period. The US situation today is not too different from Japans in 1990 yes there are differences, but many similarities, and most importantly, our solutions are nearly identical to what Japan tried. Japan has wound up with 2 decades of deation and a 10 year yield that hit 1% for the rst time in 1998.

3

S E C O N D Q U A RT E R 2 0 1 1

Source: Van R. Hoisington, The Debt Deation/Ination Debate, October 2009

Source: Van R. Hoisington, The Debt Deation/Ination Debate, October 2009

Governments have tried to step in front of this process to mitigate the pain, but as we are already seeing in Europe, the public is turning its attention to cutting spending and raising taxes. A similar phenomenon is likely at home. So the economy is likely to muddle through as it de-levers, or worse, a hiccup in the recovery results in a double dip, a further crisis of condence and a deationary shock. In either case, treasury yields are likely to fall further.

Clipping Coupons

After a three century bull market in interest rates, US Treasuries remain under-owned and unloved by all but a handful of contrary investors. We would propose that such hatred for the asset class is largely driven by the entrenched perceptions developed over a series of events during an investors career. So in some ways, investors fear of rising rates is predictably irrational provided that the highest average 10 Year Treasury yields on record were experienced during the 70s, 80s and 90s, times when the perspectives of todays investors were most heavily inuenced. Market participants recall that interest rates marched higher through the 50s, 60s and 70s, followed by a steep and steady decline over the following three decades. Few have experienced an extended period of low long term interest rates, so it makes sense that few expect such an outcome today. A decade or two of Treasury yields at two to three percent would be outside of their life experience. It would not, however, be outside the realm of history as the 10 Year Government Bond Yield averaged just 3% for the 40 years before 1960. History has repeatedly shown that secular bull markets end in a state of euphoria. We see very little evidence that the bond market exhibits any of the classic characteristics of a bubble. Bill Gross advises Buy Cheap Bonds with Safe Spread and although hed probably disagree with our call on Treasuries, we think the Bond King is onto something here. With

4

S E C O N D Q U A RT E R 2 0 1 1

the Bank of Ben articially repressing yields, investors that can identify mispriced credit will likely do much better than those focused on picking stocks for the next decade. And with money markets yielding about the same as my mattress, while stashing away unknown quantities of European junk, we think managers that can nd high yield coupons with investment grade risk offer an extremely attractive risk-reward for those baby boomers burnt by equities and hopelessly seeking income for retirement. We are still seeing a lot of value in credit research on lesser-known, illiquid names. There is still a lot of opportunity out there, but investors need to do more diligent credit work and be savvier than in the go-go years, which is exactly the way it should be.

Bottom Line

Most recessions in the post-war era have been caused by tight monetary policy. Greenspan taught us when policy is loosened, demand rebounds. But this recession was the result of a credit bust. Financial crises interfere with the transmission of lower rates to private borrowers i.e. households cant or wont borrow because the value of their collateral (i.e. their homes) has dwindled. Banks are less willing and not able to lend because their capital has been eroded by bad loans. For these reasons, recoveries following nancial crises are typically weak as banking systems are repaired and balanced sheets are rebuilt. Carmen Reinhardt demonstrates that real per capita GDP growth rates are signicantly lower during the decade following severe nancial crises and the synchronous world-wide shocks. Unemployment rates are signicantly higher in the decade that follows the crises than in the decade that preceded it. For ten of the fteen episodes examined, unemployment remains perched at a level above the pre-crises values. Wed note that high and chronic unemployment is deationary. It reduces nal demand as people dont have income to spend. Research has shown that these deleveraging periods last on average seven years, but can vary signicantly based on a multitude of factors. The current crisis has been deeper, more persistent, and widespread. Consequently, interest rates in the U.S. will stay lower for much longer than most anticipate. Household deleveraging has just begun and the savings rate is likely to head higher over time, resulting in reduced demand for credit and suppressing bond yields. Investors today have the extraordinarily pleasure of navigating an environment best described by the quants as Fat Tails. In other words, the range of outcomes during a deleveraging process is extraordinarily wide so investors must get accustomed to operating outside their comfort zone. The immediate pressure in the aftermath of crisis is clearly deationary, similar to the experience of the US in the 30s or Japan in the 90s. However, it is not hard to imagine that the massive liquidity being created by the Bernanke Fed (while allegedly not targeting the dollar), could potentially undermine any credibility remaining in the system, leading to a devaluation of at money and an equally difcult battle with ination down the road. As Peter Bernholz notes in Monetary Regimes and Ination, The gures demonstrate clearly that decits amounting to 40 per cent or more of expenditures cannot be maintained. They lead to high ination and hyperinations, reforms stabilizing the value of money, or in total currency substitution leading to the same results. At present, the federal decit is running around $1 trillion, or 20% of expenditures. This is not a problem yet, but it is also not a prudent long term scal policy. Continued decits will ultimately yield substantially negative long term consequences once our savings rate fails to increase enough to absorb the new issuance. Were not there yet. That is a story for a different day. - Christopher R. Pavese, CFA

The views expressed here are the current opinions of the author but not necessarily those of Broyhill Asset Management. The authors opinions are subject to change without notice. This letter is distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. This is not an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security and should not be construed as such. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. 5

Вам также может понравиться

- DC Cuts: How the Federal Budget Went from a Surplus to a Trillion Dollar Deficit in 10 YearsОт EverandDC Cuts: How the Federal Budget Went from a Surplus to a Trillion Dollar Deficit in 10 YearsОценок пока нет

- Debt Super CycleДокумент3 страницыDebt Super Cycleocean8724Оценок пока нет

- 2012: THE WEAK ECONOMY AND HOW TO DEAL WITH IT TO EMPOWER THE CITIZENSОт Everand2012: THE WEAK ECONOMY AND HOW TO DEAL WITH IT TO EMPOWER THE CITIZENSОценок пока нет

- BIS - The Real Effects of DebtДокумент34 страницыBIS - The Real Effects of DebtNilschikОценок пока нет

- China and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?От EverandChina and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?Оценок пока нет

- Hudson, M. Scenarios For Recovery - How To Write Down The Debts and Restructure The Financial SystemДокумент28 страницHudson, M. Scenarios For Recovery - How To Write Down The Debts and Restructure The Financial SystemxdimitrisОценок пока нет

- MONEY AND BANKING (School Work)Документ9 страницMONEY AND BANKING (School Work)Lan Mr-aОценок пока нет

- Us Debt and GoldДокумент16 страницUs Debt and Goldapi-240417748Оценок пока нет

- GreyOwl Q4 LetterДокумент6 страницGreyOwl Q4 LetterMarko AleksicОценок пока нет

- U.S. Government Debt: The Upward Spiral Continues: Olume EptemberДокумент23 страницыU.S. Government Debt: The Upward Spiral Continues: Olume Eptemberrichardck50Оценок пока нет

- Crisis Driven Report FullreportДокумент14 страницCrisis Driven Report FullreportcaitlynharveyОценок пока нет

- Lowe Comments On InflationДокумент12 страницLowe Comments On InflationJayant YadavОценок пока нет

- Federal DebtДокумент14 страницFederal Debtabhimehta90Оценок пока нет

- Charts and DescriptionsДокумент4 страницыCharts and Descriptionsemirav2Оценок пока нет

- The Next Economic Disaster: Why It's Coming and How to Avoid ItОт EverandThe Next Economic Disaster: Why It's Coming and How to Avoid ItОценок пока нет

- Understanding The Int'l MacroeconomyДокумент4 страницыUnderstanding The Int'l MacroeconomyNicolas ChengОценок пока нет

- According To Napier 10 2022Документ11 страницAccording To Napier 10 2022Gustavo TapiaОценок пока нет

- Hoisington 1 Quarter 2012Документ13 страницHoisington 1 Quarter 2012pick6Оценок пока нет

- Federal Deficits and DebtДокумент10 страницFederal Deficits and DebtSiddhantОценок пока нет

- R-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhouДокумент32 страницыR-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhoutegelinskyОценок пока нет

- The Great Mistake - How Academic Economists and Policymakers Wrongly Abandoned Fiscal Policy - Economic Policy InstituteДокумент4 страницыThe Great Mistake - How Academic Economists and Policymakers Wrongly Abandoned Fiscal Policy - Economic Policy InstituteRosana ZevallosОценок пока нет

- How Does Inflation Affect The Exchange Rate Between Two Nations?Документ32 страницыHow Does Inflation Affect The Exchange Rate Between Two Nations?Shambhawi SinhaОценок пока нет

- Fiscal Space: Special ReportДокумент19 страницFiscal Space: Special ReportNgô Túc HòaОценок пока нет

- A Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in The Era of Low Interest RatesДокумент51 страницаA Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in The Era of Low Interest RatesJohnclaude ChamandiОценок пока нет

- Hoisington Q1 2015Документ9 страницHoisington Q1 2015CanadianValue0% (1)

- BIS LeverageRootToTheCrisisДокумент5 страницBIS LeverageRootToTheCrisisHector Perez SaizОценок пока нет

- Do Budget Deficits Cause InflationДокумент8 страницDo Budget Deficits Cause InflationluminaОценок пока нет

- Follow the Money: Fed Largesse, Inflation, and Moon Shots in Financial MarketsОт EverandFollow the Money: Fed Largesse, Inflation, and Moon Shots in Financial MarketsОценок пока нет

- Does Excessive Sovereign Debt Really Hurt Growth? A Critique of This Time Is Different, by Reinhart and RogoffДокумент22 страницыDoes Excessive Sovereign Debt Really Hurt Growth? A Critique of This Time Is Different, by Reinhart and RogoffqwertyemreОценок пока нет

- GOV DEBT, DEFICITS AND ECON GROWTHДокумент7 страницGOV DEBT, DEFICITS AND ECON GROWTHmarceloleitesampaioОценок пока нет

- Carstens_SobreDesigualdadДокумент12 страницCarstens_SobreDesigualdadP ElMoОценок пока нет

- Volume 2.4 Still Bullish Apr 13 2010Документ12 страницVolume 2.4 Still Bullish Apr 13 2010Denis OuelletОценок пока нет

- Frbrich Covid19 Paper 202005 Eb PDFДокумент6 страницFrbrich Covid19 Paper 202005 Eb PDFSanchit MiglaniОценок пока нет

- Def 4Документ7 страницDef 4Guezil Joy DelfinОценок пока нет

- Deutsche Bank ResearchДокумент3 страницыDeutsche Bank ResearchMichael GreenОценок пока нет

- Agcapita July 12 2013 - Central Banking's Scylla and CharybdisДокумент5 страницAgcapita July 12 2013 - Central Banking's Scylla and CharybdisCapita1Оценок пока нет

- The New Depression: The Breakdown of the Paper Money EconomyОт EverandThe New Depression: The Breakdown of the Paper Money EconomyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- Quarterly Review and Outlook: High Debt Leads To RecessionДокумент5 страницQuarterly Review and Outlook: High Debt Leads To RecessiongregoryalexОценок пока нет

- Fiscal PolicyДокумент7 страницFiscal PolicySara de la SernaОценок пока нет

- The Looming Stagflationary Debt CrisisДокумент2 страницыThe Looming Stagflationary Debt CrisisThuy NguyenОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter (Q2-11)Документ6 страницThe Broyhill Letter (Q2-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- HIM2016Q2NPДокумент8 страницHIM2016Q2NPlovehonor0519Оценок пока нет

- Bernanke On Deflation - November 21, 2002Документ12 страницBernanke On Deflation - November 21, 2002Shyam SunderОценок пока нет

- The Inflation Doves Were Right: Bernanke Faces Tough Choices with $52T Debt OverhangДокумент14 страницThe Inflation Doves Were Right: Bernanke Faces Tough Choices with $52T Debt OverhangHan Ba Ro ShinОценок пока нет

- Investment Insights - 30-03-2008 - Quantitative Easing and Buying Toxic DebtДокумент3 страницыInvestment Insights - 30-03-2008 - Quantitative Easing and Buying Toxic DebtDemocracia real YAОценок пока нет

- Silverbullet 01Документ7 страницSilverbullet 01Matthias DtОценок пока нет

- IMF World Economic and Financial Surveys Consolidated Multilateral Surveillance Report Sept 2011Документ12 страницIMF World Economic and Financial Surveys Consolidated Multilateral Surveillance Report Sept 2011babstar999Оценок пока нет

- Cut Deficits by Cutting SpendingДокумент4 страницыCut Deficits by Cutting SpendingAdrià LópezОценок пока нет

- How India Survives High Fiscal DeficitsДокумент6 страницHow India Survives High Fiscal Deficitsandfg_05Оценок пока нет

- Two Major Issues of Fiscal Policy and Potential Harms To The EconomyДокумент10 страницTwo Major Issues of Fiscal Policy and Potential Harms To The Economysue patrickОценок пока нет

- Article On Bond Yields 26 March 2015Документ4 страницыArticle On Bond Yields 26 March 2015mitul tamakuwalaОценок пока нет

- Finshastra October CirculationДокумент50 страницFinshastra October Circulationgupvaibhav100% (1)

- The Power to Stop any Illusion of Problems: (Behind Economics and the Myths of Debt & Inflation.): The Power To Stop Any Illusion Of ProblemsОт EverandThe Power to Stop any Illusion of Problems: (Behind Economics and the Myths of Debt & Inflation.): The Power To Stop Any Illusion Of ProblemsОценок пока нет

- Economics Handout Public Debt: The Debt Stock Net Budget DeficitДокумент6 страницEconomics Handout Public Debt: The Debt Stock Net Budget DeficitOnella GrantОценок пока нет

- Financial RepressionДокумент2 страницыFinancial RepressionBudak JakartaОценок пока нет

- Stan Druckenmiller Sohn TranscriptДокумент8 страницStan Druckenmiller Sohn Transcriptmarketfolly.com100% (1)

- The Real Effects of DebtДокумент39 страницThe Real Effects of DebtCsoregi NorbiОценок пока нет

- Volume 2.2 Return of The Bond Vigilantes Feb 25 2010Документ15 страницVolume 2.2 Return of The Bond Vigilantes Feb 25 2010Denis OuelletОценок пока нет

- Around The World With Kennedy WilsonДокумент48 страницAround The World With Kennedy WilsonBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- A Brief Update On Portfolio Strategy (Nov-12)Документ8 страницA Brief Update On Portfolio Strategy (Nov-12)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Are You Smarter Than A 7th Grader (Notes)Документ37 страницAre You Smarter Than A 7th Grader (Notes)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Grave Dancer Sam ZellДокумент5 страницThe Grave Dancer Sam ZellValueWalk100% (2)

- Broyhill Letter (Aug-12)Документ8 страницBroyhill Letter (Aug-12)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Broyhill Letter (Q2-08)Документ3 страницыBroyhill Letter (Q2-08)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- HSP Thesis (May-13)Документ17 страницHSP Thesis (May-13)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Lumber Liquidators Presentation-Whitney Tilson-11!22!13Документ27 страницLumber Liquidators Presentation-Whitney Tilson-11!22!13CanadianValueОценок пока нет

- Rational Investing in Irrational MarketsДокумент70 страницRational Investing in Irrational MarketsBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Broyhill Letter (Q2-08)Документ3 страницыBroyhill Letter (Q2-08)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryДокумент4 страницыThe Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Bienville US Housing (May 2012)Документ23 страницыBienville US Housing (May 2012)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Put Me in Coach!!Документ22 страницыPut Me in Coach!!Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryДокумент3 страницыThe Broyhill Letter: Executive SummaryBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- CCH Thesis (Dec-12)Документ16 страницCCH Thesis (Dec-12)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Solid As An OAKДокумент32 страницыSolid As An OAKBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Investing Between Crises (Jun-11)Документ53 страницыInvesting Between Crises (Jun-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter (Q3-11)Документ7 страницThe Broyhill Letter (Q3-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter (Q2-11)Документ6 страницThe Broyhill Letter (Q2-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter (Q1-11)Документ7 страницThe Broyhill Letter (Q1-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Broyhill Letter (Oct-12)Документ8 страницBroyhill Letter (Oct-12)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Easy Money (Nov-11)Документ37 страницEasy Money (Nov-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Broyhill Portfolio Strategy (Apr-11)Документ42 страницыBroyhill Portfolio Strategy (Apr-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Dept of Commerce Preliminary Finding of CVDДокумент9 страницDept of Commerce Preliminary Finding of CVDBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Shorting Congress - Commentary & Strategy (January 2011)Документ6 страницShorting Congress - Commentary & Strategy (January 2011)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Broyhill Letter (Q4-10)Документ7 страницThe Broyhill Letter (Q4-10)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- Tis Mir 01.05.10Документ3 страницыTis Mir 01.05.10Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- LL - Mama Said Knock You OutДокумент17 страницLL - Mama Said Knock You OutBroyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- The Great 'Flation Debate (Nov-10)Документ33 страницыThe Great 'Flation Debate (Nov-10)Broyhill Asset ManagementОценок пока нет

- BISFED 2019 São Paulo Boccia Referee CourseДокумент3 страницыBISFED 2019 São Paulo Boccia Referee CourseErick NeoОценок пока нет

- The Avoidable War - Full ReportДокумент89 страницThe Avoidable War - Full ReportAkshat TennetiОценок пока нет

- Module 5 - Far - Activity-Answer KEYДокумент2 страницыModule 5 - Far - Activity-Answer KEYRhadzmae OmalОценок пока нет

- Distribution of Partnership ProfitsДокумент20 страницDistribution of Partnership ProfitsJOANNA ROSE MANALOОценок пока нет

- Habitat International: James M.W. Wong, S. Thomas NG, Albert P.C. ChanДокумент8 страницHabitat International: James M.W. Wong, S. Thomas NG, Albert P.C. ChangonzaloОценок пока нет

- 3.0 Overview of Swine Industry 1Документ21 страница3.0 Overview of Swine Industry 1Mandahay RegenОценок пока нет

- PolestarДокумент2 страницыPolestarHusseinОценок пока нет

- Marxist Fmaily EssayДокумент2 страницыMarxist Fmaily Essayapi-267952444Оценок пока нет

- Difference Between Production and ProductivityДокумент1 страницаDifference Between Production and ProductivityGiani Jacky OliverosОценок пока нет

- Ultra Tech Cement Internal AssessmentДокумент10 страницUltra Tech Cement Internal AssessmentDarsh KansalОценок пока нет

- 2017 To 2022 (Customer List)Документ3 страницы2017 To 2022 (Customer List)Min ThuОценок пока нет

- Lead QuesДокумент2 страницыLead QuesKameshwara RaoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3 IFRS 10 Consolidated Financial Statements Part 2Документ122 страницыChapter 3 IFRS 10 Consolidated Financial Statements Part 2Nanya BisnestОценок пока нет

- AGREEMEN1Документ56 страницAGREEMEN1Elah De LeonОценок пока нет

- Dissertation On Foreign Exchange RateДокумент6 страницDissertation On Foreign Exchange RatePaySomeoneToWriteYourPaperHighPoint100% (1)

- GKInvest New Account Types 2022Документ1 страницаGKInvest New Account Types 2022AJI PANGESTUОценок пока нет

- AFAR FinalsДокумент13 страницAFAR FinalsAmie Jane MirandaОценок пока нет

- MBA exam questions on business environment, managerial economics, organizational behavior, finance, and management controlДокумент8 страницMBA exam questions on business environment, managerial economics, organizational behavior, finance, and management controlrajsolankibarmer0% (1)

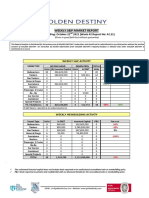

- Weekly S&P and Newbuilding Market Report SummaryДокумент7 страницWeekly S&P and Newbuilding Market Report SummarySandesh Tukaram GhandatОценок пока нет

- Financial DerivativesДокумент22 страницыFinancial Derivativesomkarmhatr2307Оценок пока нет

- Computation of Total Income Income From Salary (Chapter IV A) 1696258Документ3 страницыComputation of Total Income Income From Salary (Chapter IV A) 1696258amit22505Оценок пока нет

- Toyota Operations Management As A Competitive AdvantageДокумент8 страницToyota Operations Management As A Competitive AdvantageGodman KipngenoОценок пока нет

- 19710SP 3 BSTДокумент7 страниц19710SP 3 BSTShivansh JaiswalОценок пока нет

- Ap Macroeconomics Syllabus - MillsДокумент6 страницAp Macroeconomics Syllabus - Millsapi-311407406Оценок пока нет

- Ecodev Midterm Notes 2Документ3 страницыEcodev Midterm Notes 2Nichole BombioОценок пока нет

- Econ2122 Week 1Документ4 страницыEcon2122 Week 1Jhonric AquinoОценок пока нет

- Dynamix Luma 99acresДокумент26 страницDynamix Luma 99acresSapience RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Preparation of Financial Statements-Sole TradersДокумент5 страницPreparation of Financial Statements-Sole TradersHeavens Mupedzisa100% (1)

- Duronto AshaДокумент5 страницDuronto Ashaapi-26148947100% (1)

- SFAD Assignment 2 (23652)Документ3 страницыSFAD Assignment 2 (23652)Muhammad Raffay MaqboolОценок пока нет