Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Immnunity

Загружено:

Folukemi IkhaleaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Immnunity

Загружено:

Folukemi IkhaleaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

http://www.dawodu.com/ijalaiye1.

htm

Sovereign Immunity Under International Law Under international law, foreign heads of state, whether monarchs or presidents, embody in their persons the sovereignty of their states and when they visit or pass through the territory of another sovereign and independent country, they are wholly exempted from the local jurisdiction, both civil and criminal. The monarch or president will be covered by this immunity even if he enters into a contract of marriage under a fictitious name. Hence in Mighell v. Sultan of Johore, the Sultan of Johore in India, whilst visiting England became engaged to a young English woman to whom he disclosed his untrue identity as that of Albert Baker. The Sultan, having failed to fulfill his promise of marriage, the lady attempted to sue him for breach of promise of marriage. It was held by the British Court that a ruler of an independent sovereign state, Johore, having been so regarded for that purpose, the ruler was immune from legal process unless he decided to wave his immunity and to submit to jurisdiction. There is one crucial issue to the sovereign immunity being touted in favour of Governor Alamieyeseigha. This crucial issue relates to the status of component units of federal state. The right answer would seem to have been provided by Lord Denning in the case of Mellenger v. New Brunwick Development Corporation. In this case, Lord Denning emphasised that "Since under the Canadian Constitution, each provincial government, within its own sphere, retained its independence and autonomy under the Crown ... It follows that the Province of New Brunswick is a sovereign state in its own right and entitled, if it so wishes, to claim sovereign immunity". Also, Article 28 of The European Convention of state Immunity 1972, provides that constituent states of a federal state do not enjoy immunity ipso facto, although this general principle is subject to the proviso that federal state parties may declare by ratification of the convention that their constituent states may invoke the benefits of (sovereign immunity) and may carry out the obligations of the convention. It is, therefore, strongly submitted that each of the 36 states of Nigeria does

not constitute an "independent sovereign state" and its governor cannot, therefore, claim "sovereign immunity" in international law. Afterwards, the rationale for independent sovereign immunity in international law is "par in parem non habet imperium". This means that since the independent sovereign states of the world are equal, one sovereign power cannot exercise jurisdiction over another sovereign power. It cannot, therefore, be over-emphasised that since each of the 36 states of Nigeria is neither independent nor sovereign, it cannot operate on the same footing as independent and sovereign states under international law. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was, therefore, right in its recent statement that in Nigeria, "immunities for governors and their deputies do not extend beyond Nigerian shores". It is, however, submitted that the governor of any of the 36 states of Nigeria visiting another country as the Representative of the President of Nigeria, ought to enjoy sovereign immunity in a representative capacity during the period of the representation. Consequently in that case, the immunity enjoyed by such a governor should not be higher but only similar to the immunity enjoyed by a diplomatic envoy. In international law, the person of a diplomatic agent is inviolable and he is immune from any form of arrest or detention and from all criminal proceedings. It is his duty to respect the criminal law and police regulations of the country, but if he breaks them, the only action that may normally be taken against him is a diplomatic complaint to his government or, in an extreme case, a demand for his withdrawal as a persona non grata. It is possible of course in international law for a sovereign state to waive expressly or impliedly the immunity of a diplomatic representative within the jurisdiction of the receiving state. A fortiori, the President of a country may, for good cause, decide to waive the immunity enjoyed by a governor of a state representing him in another country if such a governor engages in an act that is contrary or inimical to the policy of the government of his home country. In the instant case, even if it is conceded that the Governor of Bayelsa State obtained permission from President Obasanjo before travelling abroad, and even if it can be inferred from such a permission that immunity is thereby conferred on him during his absence abroad, President Obasanjo is still morally bound to waive such immunity in respect of money-laundering perpetrated by him since the war against corruption is currently the main focus of his administration. In this connection, it has rightly been observed: "Under the presidential system, the personality of the President, his style,

preferences and dislikes will make a great imprint on the direction government policy goes. Thus, it is the perception of the President about what is crucial to the country that will, in most cases, become the main focus of the administration". Indeed, it can be inferred from a recent statement of President Obasanjo that he had already given a nod to the arrest of Governor Diepreye Alamieyeseigha by the British police for money-laundering activities. The arrest was made on Thursday, September 15, 2005. In this connection, President Obasanjo was quoted as saying that "no Nigerian was above the law and that the campaign in Nigeria against corruption in high places was bearing fruits". President Obasanjo further stated: "There had been no other instance in the history of Nigeria where top government officials were arrested over corruption while they were still in office as it is being done now". In other words, President Obasanjo welcomed the arrest of the Bayelsa Governor as an evidence of the potency of his anti-corruption crusade. It appears that President Obasanjo's support for the arrest and detention of Governor Alamieyeseigha must have been partly influenced by a strong petition addressed to the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) by some citizens of Bayelsa State against the governor, revealing that some members of his family had looted from the Bayelsa's government treasury the following huge sums of money: 1,043,655.79 USD; 173,365.41 Great Britain Pound; and 556,455,893.34 Naira. Coincidentally, President Obasanjo's stand has been further vindicated by the information recently credited to Alhaji Nuhu Ribadu (Chairman of (EFCC) that Governor Alamieyeseigha allegedly owns many houses in London estimated at 10 million British Pounds. Conclusion The case of Governor Alamieyeseigha has brought to the fore the discussion as to whether it is desirable to continue to retain in the Nigerian Constitution Section 308 which confers immunity on the President, the Vice-President and the governors of the 36 states of the federation. In my considered judgment, the immunity conferred by Section 308 has done more harm than good since it has been used by some of the officials

concerned as a licence for stealing public funds with reckless abandon. It is, therefore, strongly submitted that the section be completely expunged from the constitution so that the officials concerned will no longer have legal cover for plundering government's treasuries for their own benefits. Currently, Mr. Tafa Balogun, the former Inspector-General of Police, is being tried for official corruption. Once Section 308 of the Constitution is expunged, all the corrupt chief executive and other officials at the federal and state levels will be similarly treated. After all, what is good for the gander is good for the goose. At this juncture, it is pertinent to point out that even in modern international law, sovereign states no longer enjoy absolute immunity but only restrictive immunity as clearly shown in the celebrated case of Pinochet, the former President of Chile. Before the case of Pinochet, it was thought that a Head of State or a former Head of State was entitled to claim absolute immunity from the jurisdiction of national courts whether in criminal or civil process. Pinochet of Chile relied on this ancient rule and he initially won his case at the Divisional Court (i.e. High Court) of Britain. However, The House of Lords, Britain's highest Court, subsequently ruled on Wednesday, November 25, 1998, that the charges against Pinochet, including torture and hostagetaking, could not be considered official functions and, therefore, the immunity normally granted to a former Head of State did not apply to him. The court further stated that heads of states who have committed crimes particularly those against humanity, are responsible for those crimes and may be prosecuted anywhere. It has been persuasively and attractively argued that money-laundering activities, particularly in respect of the poor state of Bayelsa, would constitute a crime against humanity in view of the fact that in such circumstances, it would deplete or empty the state's treasury, thus, creating armies of unemployed and hungry youths who frequently resort to violence and other nefarious acts as a means of earning a livelihood. The fact that an unemployed/hungry man, more often than not, resort to violence, has been explained by Chief Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu in a way that is unanswerable: "A hungry man is an angry man; an angry man is an unreasonable man; an unreasonable man is a violent man". Also, the rule that foreign states now enjoy only restrictive sovereign immunity in the territories of one another is buttressed by the decision of the British Court of Appeal in the case of Trendtex Corporation v. Central Bank of Nigeria. In this landmark case, the court rejected the doctrine of absolute

immunity accorded sovereign states in the British Courts especially in relation to trading activities. In reaching this conclusion, the court took into account the fact that majority of states of the world now favour the principle of restrictive immunity since they now distinguished pragmatically between foreign state activities jure imperii and jure gestionis. For the former, they grant immunity, for the latter, they refuse it. The distinction between these two types of state activity rests on the assumption that an adequate distinction between public and private activities can always be made. Finally, the following must be said. As far as Nigeria is concerned, Diepreye Alamieyeseigha is still the legitimate Governor of Bayelsa State. If he absconds from the United Kingdom and suddenly reappears in Nigeria, he automatically becomes an untouchable person because he cannot be arrested by the police or prosecuted before the Nigerian court since he enjoys immunity under Section 308 of the Constitution of The Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999. However, he is currently in the United Kingdom still being charged before the British Court. His diplomatic status is yet to be determined as to whether he enjoys sovereign or diplomatic immunity before the British Court. The practice in the United Kingdom is for each Head of Mission to submit in advance to the Foreign Office the names of those persons for whom any form of diplomatic status is claimed, and if accepted, they are included in a published list to which the courts will refer from time to time. In case of doubt, the statement of the Foreign Office of Britain will be treated as conclusive on the matter, and this automatically leads in appropriate cases, to the grant of privileges and immunities. In view of the foregoing, the only cause open to Nigeria for now is to adopt an attitude of wait-and-see.

http://odili.net/news/source/2005/oct/14/315.html

International law, governor alamieyeseigha and sovereign immunity By Itse Sagay Friday, October 14, 2005 I have read the recent contribution of Professor David Ijalaiye on the subject of the entitlement of Governor Diepreye Alamieyeseigha to sovereign immunity, with great interest. Professor Ijalaiye is a long standing scholar of International Law and his views deserve the utmost respect. Indeed, we both taught the International Law course at the University of Ife in the early seventies and we were both joint examiners in that programme. I am therefore not surprised at all about the well researched paper published at page 73 of the Punch Newspaper of Monday 10th October 2005. 2. Understandable Errors However, inspite of his impeccable background in International Law, the paper suffers from some fundamental errors, some flowing from an improper appreciation of federalism, others from inadequate analysis of established facts and thirdly from lack of access to existing materials and the latest developments and thinking on the subject matter. The best and most brilliant of International Lawyers can be forgiven for these understandable lapses because the subject of the sovereign immunity of a federating unit (State) within a federation is obscure, rarely discussed and almost recondite (to borrow a very apt term indicating the nature of our subject matter). Indeed, University undergraduate lectures in International Law rarely ever include this subject. It was never specially discussed during my postgraduate student programme in International Law and I never specifically taught it myself in my International Law classes at Ife and Benin. State immunity was discussed. No one bothered to delve into the details of what constitutes a state for the

purposes of immunity. Now that we are suddenly and frontally confronted with it, it would appear that all available materials and precedents point in the direction of states in a federation and their Heads of State/ Government, being entitled to state and sovereign immunity. However, I must commence by pointing out the fundamental flaws and errors in Professor Ijalaiyes presentation. 3. DOMESTIC IMMUNITY In his discussion of Sovereign Immunity under Nigerian Law, Ijalaiye, relying on section 308 of our Constitution (full immunity of the President, Vice President, Governors, and Deputy- Governors) reaches the following contradictory conclusion. "In practical terms, President Olusegun Obasanjo is currently the President under the Nigerian Constitution and he enjoys sovereign immunity in that capacity. Also Alamieyeseigha, as the head of the Government of Bayelsa State enjoys some measure of immunity in that capacity. Section 308 of the constitution makes identical provisions for the immunity of the President and the Governors. There can therefore be no basis for concluding that whilst the President enjoys sovereign immunity "in that capacity", Governor Alamiesiegha who is protected by identical provisions in the same section " as head of the Government of Bayelsa State enjoys some measure of immunity in that capacity". Where in section 308 is the President granted sovereign immunity and Governors granted the down graded "some measure of immunity" What does "some measure of immunity" mean in the context of section 308 of the constitution which I now proceed to reproduce below. "(1) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this constitution, but subject to subsection (2) of this section (a) no civil or criminal proceedings shall be instituted or continued against a person to whom this section applies during his period of office; (b) a person to whom this section applies shall not be arrested or imprisoned during that period either on pursuance of the process of any court or otherwise; and (c) no process of any court requiring or compelling the appearance of a person to whom this section applies, shall be applied for or issued: (3) This section applies to a person holding the office of President or VicePresident, Governor or Deputy Governor; and the reference in this section to "period of office" is a reference to the period during which the person holding such office is required to perform the functions of the office".

It can thus be seen that there is no distinction whatsoever between the immunity granted the President and that granted a Governor under section 308. Therefore the introduction of the term sovereign immunity for the President and some measure of immunity with respect to Governors, is an extra or indeed unconstitutional importation of foreign provisions into the constitution by Ijalaiye. Infact for both the President and Governors, the correct term for the identical immunity they enjoy under our constitution is absolute immunity. (ii) Secondly, Professor Ijalaiye further states quite correctly that the President is granted the executive powers of the Federation in section 5(1) of the constitution, whilst section 5(2) of the same constitution vests the executive powers of each state in the Governor of that State. Again, very sadly Ijalaiye draws different conclusions from similar facts. For according to him, "hence for the purposes of International Law, it is only the president that enjoys "independent sovereign immunity". How on earth does such a conclusion arise from sections 5(1) and 5(2) of the constitution granting the President and Governors executive powers in their exclusive areas of authority? The Presidents executive powers are limited to the items in the Exclusive Legislative List and the Concurrent List. The Governors executive powers encompass not only those in the Concurrent Legislative List but go on to include all residual subjects, i.e., items not listed in the Exclusive and Concurrent Lists. That is why International Law describes the powers of a Federal Government as enumerative (that which has to be specifically listed) whilst a federating states powers are termed plenary. (meaning, complete, absolute). Indeed, when modern federations first emerged in 1789, with the coming together of the 13 United States Colonies, first as a confederation and subsequently as a federation, the international community looked at the new federal entity with suspicion and doubt, and whilst they acknowledged the sovereignty and individual international personality of the federating states, it was with reluctance that the international personality of the new federal state as an independent sovereign entity, was acknowledged. The present unchallenged international personality of a federal state only emerged over a period of time. 4. LOCATION OF SOVEREIGNTY IN A FEDERATION The mistake Ijalaiye made repeatedly in his otherwise admirable contribution, was the assumption that a federation has a single undivided sovereignty. That is incorrect. A federations sovereignty is split between the federal state and the federating states. Let us look at some authoritative definitions of federalism.

According to Professor B.O. Nwabueze: "Federalism may be described as an arrangement whereby powers within a multi-national country are shared between a federal or central authority, and a number of regionalized governments in such a way that each unit including the central authority exists as a government separately and independently from the others, operating directly on persons and property within its territorial area, with a will of its own and its own apparatus for the conduct of affairs and with an authority in some matters exclusive of all others. In a federation, each government enjoys autonomy, a separate existence and independence of the control of any other government. Each government exists, not as an appendage of another government (e.g., of the federal or central government) but as an autonomous entity in the sense of being able to exercise its own will on the conduct of its affairs free from direction by any government. Thus, the Central government on the one hand and the State governments on the other hand are autonomous in their respective spheres". As Wheare put it, "the fundamental and distinguishing characteristic of a federal system is that neither the central nor the regional governments are sub-ordinate to each other, but rather, the two are co-ordinate and independent". In short, in a federal system, there is no hierarchy of authorities, with the central government sitting on top of the others. All governments have a horizontal relationship with each other". Now let us see how federalism is defined in International Law. In Whitemans Digest of International Law, the legal status of a federating unit (State) within a federation is defined as follows; "A federal State is a political contrivance intended to reconcile national unity and power with the maintenance of States rights. It is a union of a number or body of independent States whose territories are contiguous and whose citizens have certain affinities, either racial, ethnological or traditional, who have a common historical background or heritage, a community of economic interests, and feel a craving for spiritual and national unity, but at the same are anxious to maintain the identity and independence of their States, which are not strong enough in modern times to face external industrial competition or military menace. It is an organic union. A federal State is a distinct fact. The federating States also remain distinct facts" "A federal State is a perpetual union of several sovereign States which has organs of its own and is invested with power, not only over the memberStates, but also over their citizens. The union is based, first on an international treaty of the member-States, and, secondly, on a subsequently accepted constitution of the federal State. A federal State is said to be a real

State side by side with its member-States, because its organs have a direct power over the citizens of those member-States. This power was established by American jurists of the eighteenth century as a characteristic distinction between a federal State and confederated States, and Kent as well as Story, the two later authorities on the Constitutional Law of the United States, adopted this distinction, which is indeed kept up until to-day by the majority of writers on politics. Now if a federal State is recognized as itself a State, side by side with its member-States, it is evident that sovereignty must be divided between the federal State on the one hand, and on the other, the member-States. This division is made in this way, that the competence over one part of the objects for which a State is in existence is handed over to the Federal State, whereas the competence over one part remains with the member-States. Within its competence the federal State can make laws which bind the citizens of the member-States directly without any interference by these member-States. On the other hand, the member-States are totally independent as far as their competence reaches." (See Vol. 1, para 23 at p.308).

In the light of the split sovereignty of federations, the federating states have a certain degree of international personality and the head of State/Government of a federating State is entitled to sovereign immunity. The original independence and sovereignty of the states, nations and autonomous communities constituting the present state of Nigeria was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Nigeria in Attorney-General of the Federation v The Attorney-General of Abia State and 36 others in the following passage from the leading Judgment of Ogundare, JSC: "Until the advent of the British colonial rule in what is now known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Nigeria, for short), there existed at various times various sovereign states known as emirates, kingdoms and empires made up of ethnic groups in Nigeria. Each was independent of the other with its mode of Government indigenous to it. At one time or another, these sovereign states where either making wars with each other or making alliances, on equal terms. This position existed throughout the land now known as Nigeria. In the Niger-Delta area, for instance, there were the Okrikas, the Ijaws, The Kalabaris, the Efiks, the Ibibios, the Urhobos, the Itsekiris, etc. Indeed certain of these communities, (e.g Calabar) asserted exclusive right over the narrow waters in their area. And because of the terrain of their area, they made use of the rivers and the sea for their economic advancement in fishing and trade and in making wars too! The rivers and the sea were their only means of transportation. Trade then was not only among themselves but with foreign nations particularly the European nations who sailed to their shores for palm oil, kernel and slaves".

([2002] Vol. 16, WRN, 1 at p.68) 5. THE STATUS OF FEDERATING STATES WITHIN A FEDERATION AND IN INTERNATIONAL LAW The leading English Practitioners book in International Law, Oppenheims International Law edited by Sir Robert Jennings QC, (former President of the International Court of Justice) and Sir Arthur Watts KCMG, QC (former Legal Adviser to the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office), states as follows; "Since a federal state is itself a state, side by side with its member states, sovereignty is divided between the federal state on the one hand, and, on the other, the member states; competence over one part of the objects for which a state exists is vested in the federal state. Whereas competence over the other part remains with the member states. Within its competence the federal state can make laws which bind the citizen of the member states directly without any interference by these member states. On the other hand, the member states are totally independent as far as their competence reaches. For International law this division of competence is of interest insofar as it concerns competence in international matters. Since it is always the federal state (and not the member states) which is competent to declare war, make peace, conclude political treaties, and send and receive diplomatic envoys, the federal state is itself an international person, with all the rights and duties of a sovereign state in international law. On the other hand, the international position of the member states is not so clear. There is no justification for the view that they are necessarily deprived of any status whatsoever within the international community; while they are not full subjects of international law, they may be international persons for some purposes. Everything depends on the particular characteristics of the federation in question. Thus two member states of the Soviet Union a federal state since 1918 are separate members of the United Nations and are parties to many treaties". (See Oppenheim, Vol.1. Part 1. Peace, 9th edition, 1992, para 75, p.249. The eminent Editors of Oppenheim go on to demonstrate that federating units (states) within a federation are subjects of international law and that they and their heads of government are covered by state immunity. "The Constitution of federations may allow member states to conclude treaties. Thus Article 32 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany provides that insofar as the member states are competent to legislate they may, with the approval of the federal Government, conclude treaties with foreign states. Similarly, the member states of Switzerland retain the right to conclude treaties with foreign states as regards matters of minor interest. In the judicial settlement of disputes which have arisen

between member states of a federation, the municipal courts in question have often had recourse to rules of international law. Furthermore, member states have in a number of cases been granted immunity from jurisdiction by the courts of other countries, at least so far as concerns matters in which the member states retain their sovereign powers. Member states lacking international status may also sometimes have their own representatives abroad although they will not be diplomatic agents in the usual sense of that term". I shall of course later supply more modern and detailed examples of the current theory and practice of sovereign immunity for federating states. The two cases cited by Professor Ijalaiye on sovereign immunity are in support of the entitlement of federating states in a federation and their heads, to sovereign immunity. In Mighell v. Sultan of Jahore a 19th Century case, the Sultan who successfully claimed immunity from suit in response to an action against him for breach of promise of marriage, was the head of a tiny sultanate inside India, which was itself not yet an independent country. Yet he was held immune from British legal process and the English woman was denied a remedy. Two points need to be noted in this case. (i) Jahore was not a sovereign state. It was a territory inside colonial India. (ii) The Sultan was in Britain on a private visit and made the promise to marry the English lady under a false name. Nevertheless, the Sultan was granted immunity from suit. (See [1895] 1Q.B. 149) When a sovereign is within a foreign jurisdiction, it is irrelevant that he is there in a private capacity, because his immunity is absolute since it is ratione personae, i.e., it covers his person completely. In Mellenger v. New Brunswick Development Corporation also cited by Ijalaiye, a federating unit in Canada was granted sovereign immunity by the English Court of Appeal. We shall come to this case later. 6. INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY OF FEDERATING STATES Of all the errors contained in the Professors article, perhaps the most grave and disturbing is the suggestion or assertion that the Governor of a Nigerian State visiting another country could be regarded as representing the President and could therefore enjoy immunity in a representative capacity "during the period of representation consequently in that case, the immunity enjoyed by such a governor should not be higher but only similar to the immunity enjoyed by a diplomatic envoy". In the first place the very idea that a Governor of an autonomous and independent state sharing sovereignty within a federation with the federal

government could be a representative of the President, constitutes a major assault on federalism. The Governor of a State is directly and independently elected by his People into office. He has a separate government, territory, population, judiciary, civil service and legislature from the Federal Government. He is sovereign in his own sphere just as the President is sovereign in his own sphere. Their Governments are parallel Governments independent of each other. Under no circumstance can a State Governor represent the President inside and outside Nigeria. They are both Heads of independent Governments, as was stated in the definitions of Federalism. The Diplomat is a Federal Civil servant who is under to the Federal Government. The Laws governing his immunity are different and internationally it is the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic immunity. States and their Heads or sovereigns are not covered by this Convention. Rather, they are covered by Customary International Law. The United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and their Properties, concluded on 2nd December 2004, which shall enter into force on the 30th day following the ratification, acceptance or approval by states does not modify the absolute immunity enjoyed by Heads of State including the Head of a Federating State. Rather customary international law on state and sovereign immunity is specifically preserved by the Convention. More of this later. It is standing federalism and Constitutional law on its head to suggest or imply that the Head of the Federal Government can waive the immunity of an independent and autonomous co-government in a federation. It is a faux pas of enormous proportions and a consequence of prolonged military rule, culture and mentality. Only State Governors can waive their own immunity and that of their sub-ordinates in the States service. 7. THE PINOCHET CASE

Again, the learned Professor missed the ratio of the Pinochet case. All that case decided was that a Head of State who commits or authorizes the commission of a crime against humanity, or a war crime, or genocide, etc, can be tried for his crimes after he has left office. His immunity is therefore effective whilst he remains in office and he cannot be arrested, prosecuted or imprisoned whilst in office. Two more points about this case may be noted. 1. His loss of immunity after leaving office is limited exclusively to crimes against humanity, war crimes genocide and such major international crimes regarded as belonging to the class of rules called jus cogens, i.e. preemptory rules of International Law. For this class of crimes, his immunity ratione

personae is down graded to immunity ratione materiae after he leaves office. This means instead of absolute personal immunity, only his official acts are covered. 2. If the offence does not belong to this category, then a head of state or government cannot even be prosecuted after he has left office. His immunity continues to be ratione personae. This comes out clearly in the following two passages from the Pinochet case, officially known as Stipendiary Magistrate and others, exparte Pinochet Ugarte (No.3) [1999] 2 All E.R. 97 at p.111-2. Lord Browne Wilkinson put the matter succinctly as follows: "It is a basic principle of international law that one sovereign state (the forum state) does not adjudicate in the conduct of a foreign state. The foreign state is entitled to procedural immunity from the processes of the forum state. This immunity extends to both criminal and civil liability. State immunity probably grew from the historical immunity of the person of the monarch. In any event, such personal immunity of the head of state persists to the present day: the head of state is entitled to the same immunity as the state itself. The diplomatic representative of the foreign state in the forum state is also afforded the same immunity in recognition of the dignity of the state which he represents. This immunity enjoyed by a head of state in power and an ambassador in post is a complete immunity attaching to the person of the head of state or ambassador and rendering him immune from all actions or prosecutions whether or not they relate to matters done for the benefit of the state. Such immunity is said to be granted ratione personae". In this case, Lord Goff also declared as follows: "There can be no doubt that the immunity of a head of state, whether ratione personae or ratione materiae, applies to both civil and criminal proceedings. This is because the immunity applies to any form of legal process. The principle of state immunity is expressed in the Latin maxim par in parem non habet imperium, the effect of which is that one sovereign state does not adjudicate on the conduct of another. This principle applies as between states, and the head of a state is entitled to the same immunity as the state itself, as are the diplomatic representatives of the state. That the principle applies in criminal proceedings is reflected in the 1978 Act, in that there is no equivalent provision in Pt III of the 1978 Act to s 16(4) which provides that Pt 1 does not apply to criminal proceedings." Therefore when the issue is that of the personal immunity of a Head of State or Government, the only restriction whatsoever other than the limited case of crimes against humanity, torture, genocide etc for which his immunity is lifted only after he has left office. Subject to that the sovereigns immunity remains absolute.

7. CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Ijalaiyes suggestion that money laundering, could be classified as a crime against humanity is a feeble and futile one in the face of the rules of International Law. This is not a matter involving conjecture,, suggestions, proposals, hypothesis etc. The position is clear and settled. Crimes against humanity are listed in Article 7 of the Statute of the International Criminal Court and money laundering is not one of them. They are (a) Murder, (b) Extermination, (c) Enslavement, (d) Deportation or forcible transfer of populations, (e) Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of International Law, (f) Torture, (g) Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity, (h) Persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religions, gender or other grounds recognized as impermissible in International Law. (i) Enforced disappearance of persons (ii) The crime of apartheid (iii) Other inhuman crimes of a similar character.

Thus crimes against humanity are limited to breaches of civil rights, as in chapter 4 of the Nigerian Constitution, and not economic, social and cultural rights as in chapter 2. At the International Law level, they are limited to violations of the rights contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) and not of the rights contained in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966). Therefore money laundering cannot by the wildest stretch of the imagination be described as a crime against humanity. You cannot re-classify an offence expost facto, the actus reus. The issue of restrictive immunity, by which states are no longer entitled to immunity in respect of trading and commercial activities (acts jure gestionis) is totally irrelevant to this case. States are generally only entitled to immunity for political and public acts (jure imperri) and not for commercial transactions (jure gestionis). These restrictions on state activities do not affect the absolute immunity still being enjoyed by the persons of sovereigns (heads of state/government), diplomatics and their families. Therefore, the Trendex Case in which the Central Bank of Nigeria was denied immunity in its cement buying transaction (commercial activity) is totally irrelevant to the present case which raises the question whether the Head of State and Government of a

state within a federation is entitled to immunity ratione personae (absolute immunity of the person) when he is in a Foreign Country. 8. FEDERATING STATES AND SOVEREIGNS IMMUNITY Now, the question still remains, what is the Legal status of a federating state in International Law, and to what extent are they and their Heads of State/Government entitled to immunity. I have already provided some information on this issue above, but there is need to further buttress it. The international status of federating unit within a federation and the entitlement to immunity of the heads of these federating units is even better expressed in the eight edition of Oppenheim"s International Law, edited by H. Lauterpacht, late Whewell Professor of International Law in the University of Cambridge and former President of International Court of Justice, in the following passage (See para 65 and p. 119) "A State in it normal appearance does possess independence all round, and therefore full sovereignty. Yet there are States in existence which certainly do not possess full sovereignty, and are therefore named not-full sovereign States. All States which are under the suzerainty or under the protectorate of another State, or are member-States of a so-called federal State, belong to this group. All of them possess supreme authority and independence with regard to a part of the functions of a State, whereas with regard to another part they are under the authority of another State. This fact explains the doubt as to whether such not full sovereign states can be international persons and subjects of the Law of Nations at all. That they cannot be full, perfect, and normal subjects of International Law there is no doubt. But it is inaccurate to maintain that they can have no international position whatever. They often enjoy in many respects the rights, and fulfill in other points the duties, of International Persons. They frequently send and receive diplomatic envoys, or at least consuls. They often conclude commercial or other treaties. Their monarchs enjoy the privileges which, according to the Law of Nations, the Municipal Laws of the different States must grant to the monarchs of foreign State. No other explanation of these and similar facts can be given except that these not-full sovereign States are in some way or another International Persons and subjects of International Law".

The most recent authority on this issue is the United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and their Property, concluded on December 2, 2004. Article 2 (b) defining States, classifies as States: at 2(b) (ii) "Constituent units of a federal state or political subdivisions of the state, which are entitled to perform acts in the exercise of sovereign authority and

are acting in that capacity". Law making, (Legislature) State judiciary, a civil service, directly elected Governors with sole executive powers, exclusive powers in the plenary areas of governance in their territories (health, agriculture, education, housing, environment, regional planning etc) are all indices of sovereignty. The Convention, is basically intended to codify the customary rules of International Law as they relate to acts jure imperri and jure gestionis, and in article 3, it specifically exempts diplomatic missions, Heads of State and other entities enjoying special protection under special conventions, treaties or customary International Law, from the restrictive provisions of the Convention. Thus articled 3(2) states that "The present Convention is without prejudice to privileges and immunities accorded under international law to heads of state ratione personae". In its 1991 draft, (U.N Document A/46/10) the International Law Commission (which drafted the Convention commented that this explicit exclusion was intended to preserve existing rules of customary International Law. These rules provide that heads of state are absolutely immune and that even former heads of state are entitled to immunity for their official acts. Again in Halsburys Laws of England 4th Edition, para 1549, "sovereign state" is defined as follows: "For the purposes of the rules of sovereign immunity, the term "sovereign state" applies not only to the foreign state itself, but also to the head of state personally, and to the government or any department of government including in the case of composite states, the government of a province [federating unit] of the state. It includes independent countries of the commonwealth and their sub-divisions and states under British protection". In Mellenger and Another v New Brunswick Development Corporation ([1971] 2 All E.R. 593), cited by Ijalaiye, the Plaintiffs, Canadian citizens, brought a claim against the defendant corporation, which was owned and controlled by the State of New Brunswick, a federating unit in the state of Canada. Upholding a claim of state immunity put forward by the defendant corporation, the English Court of Appeal held that it was entitled to plead immunity and set the writ aside on the following grounds: "(i) although a province (State) of Canada under the federal constitution of Canada, the province of New Brunswick retained within its own sphere its independence and autonomy and was thus a sovereign state in its own right entitled to claim sovereign immunity. (ii) the defendant corporation could avail itself of that sovereign immunity since, by the express provisions of the 1959 Act setting it up, it was in the same position as a government department; and even apart from the Act, the corporations functions as carried out in practice, showed that it was

carrying out the policy of the government of New Brunswick and was its alter ego. In coming to the above conclusion, Lord Denning M.R. stated thus: "It was suggested by counsel for the plaintiffs that Province of New Brunswick does not qualify as a sovereign state so as to invoke the doctrine of sovereign immunity. But the authorities show decisively the contrary. The British North America Act 1867 gave Canada a federal constitution. Under it the powers of government were divided between the dominion government and the provincial governments. Some of those powers were vested in the dominion government. The rest remained with the provincial governments. Each provincial government, within its own sphere, retained its independence and autonomy, directly under the Crown. The Crown is sovereign in New Brunswick for provincial powers, just as it is sovereign in Canada for dominion powers: See Maritime Bank of Canada (Liquidators) v Receiver-General of New Brunswick. It follows that the Province of New Brunswick is a sovereign state in its own right, and entitled, if it so wishes, to claim sovereign immunity".

In a concurring judgment, Salmon L.J. had this to say: "Before us the point has been taken at the last moment on behalf of the corporation that a writ cannot be issued out of the jurisdiction calling upon them to appear before the courts of this country because it is entitled to sovereign immunity. I have come to the conclusion, in spite of counsel for the plaintiffs attractive argument, that this point which was not taken before the judge is unanswerable. There can be no doubt, I think, that the government of New Brunswick is sovereign within its own sphere of influence. That appears from Maritime Bank of Canada (Liquidators) v Receiver-General of New Brunswick and also from Hodge v R.

Now the Canadian Federation and the Nigerian Federation are similar types of federation and the English Courts cannot apply one principle to New

Brunswick Canada and the opposite to Bayelsa State of Nigeria. Furthermore there are numerous other cases, English and otherwise confirming the right of a state within a federation and its Head of State/Government to immunity, which need not be paraded in a newspaper article. But the conclusion to which a careful and comprehensive enquiry into this matter leads inevitably to, is that Governor Depreye Alamieyeseigha, is entitled to absolute immunity ratione personae in England, and should be released immediately with apologies, to return to his State and People. Ijalaiye is an emeritus professor of law at the Obafemi Awolowo University, (OAU), Ile-Ife, Osun State.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- A Winning Formula: Debrief For The Asda Case (Chapter 14, Shaping Implementation Strategies) The Asda CaseДокумент6 страницA Winning Formula: Debrief For The Asda Case (Chapter 14, Shaping Implementation Strategies) The Asda CaseSpend ThriftОценок пока нет

- Mercury 150HPДокумент5 страницMercury 150HP이영석0% (1)

- Heat TreatmentsДокумент14 страницHeat Treatmentsravishankar100% (1)

- Alternator: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент8 страницAlternator: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAsif Al FaisalОценок пока нет

- AkДокумент7 страницAkDavid BakcyumОценок пока нет

- SMK Techno ProjectДокумент36 страницSMK Techno Projectpraburaj619Оценок пока нет

- Data Mining - Exercise 2Документ30 страницData Mining - Exercise 2Kiều Trần Nguyễn DiễmОценок пока нет

- Descriptive Statistics - SPSS Annotated OutputДокумент13 страницDescriptive Statistics - SPSS Annotated OutputLAM NGUYEN VO PHIОценок пока нет

- VISCOROL Series - Magnetic Level Indicators: DescriptionДокумент4 страницыVISCOROL Series - Magnetic Level Indicators: DescriptionRaduОценок пока нет

- Department of Labor: 2nd Injury FundДокумент140 страницDepartment of Labor: 2nd Injury FundUSA_DepartmentOfLabor100% (1)

- CSA Report Fahim Final-1Документ10 страницCSA Report Fahim Final-1Engr Fahimuddin QureshiОценок пока нет

- IP Based Fingerprint Access Control & Time Attendance: FeatureДокумент2 страницыIP Based Fingerprint Access Control & Time Attendance: FeaturenammarisОценок пока нет

- Majalah Remaja Islam Drise #09 by Majalah Drise - Issuu PDFДокумент1 страницаMajalah Remaja Islam Drise #09 by Majalah Drise - Issuu PDFBalqis Ar-Rubayyi' Binti HasanОценок пока нет

- Dr. Li Li Prof. Feng Wu Beijing Institute of TechnologyДокумент20 страницDr. Li Li Prof. Feng Wu Beijing Institute of TechnologyNarasimman NarayananОценок пока нет

- Manuscript - Batallantes &Lalong-Isip (2021) Research (Chapter 1 To Chapter 3)Документ46 страницManuscript - Batallantes &Lalong-Isip (2021) Research (Chapter 1 To Chapter 3)Franzis Jayke BatallantesОценок пока нет

- E Nose IoTДокумент8 страницE Nose IoTarun rajaОценок пока нет

- DR-2100P Manual EspДокумент86 страницDR-2100P Manual EspGustavo HolikОценок пока нет

- IOSA Information BrochureДокумент14 страницIOSA Information BrochureHavva SahınОценок пока нет

- Dreamweaver Lure v. Heyne - ComplaintДокумент27 страницDreamweaver Lure v. Heyne - ComplaintSarah BursteinОценок пока нет

- A CMOS Current-Mode Operational Amplifier: Thomas KaulbergДокумент4 страницыA CMOS Current-Mode Operational Amplifier: Thomas KaulbergAbesamis RanmaОценок пока нет

- MEMORANDUMДокумент8 страницMEMORANDUMAdee JocsonОценок пока нет

- We Move You. With Passion.: YachtДокумент27 страницWe Move You. With Passion.: YachthatelОценок пока нет

- Automatic Stair Climbing Wheelchair: Professional Trends in Industrial and Systems Engineering (PTISE)Документ7 страницAutomatic Stair Climbing Wheelchair: Professional Trends in Industrial and Systems Engineering (PTISE)Abdelrahman MahmoudОценок пока нет

- EASY DMS ConfigurationДокумент6 страницEASY DMS ConfigurationRahul KumarОценок пока нет

- Lenskart SheetДокумент1 страницаLenskart SheetThink School libraryОценок пока нет

- Pthread TutorialДокумент26 страницPthread Tutorialapi-3754827Оценок пока нет

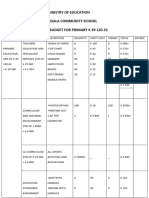

- Ministry of Education Musala SCHДокумент5 страницMinistry of Education Musala SCHlaonimosesОценок пока нет

- Small Signal Analysis Section 5 6Документ104 страницыSmall Signal Analysis Section 5 6fayazОценок пока нет

- Creative Thinking (2) : Dr. Sarah Elsayed ElshazlyДокумент38 страницCreative Thinking (2) : Dr. Sarah Elsayed ElshazlyNehal AbdellatifОценок пока нет

- Bea Form 7 - Natg6 PMДокумент2 страницыBea Form 7 - Natg6 PMgoeb72100% (1)