Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

A Revolution

Загружено:

Akachi OkoroИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Revolution

Загружено:

Akachi OkoroАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A revolution (from the Latin revolutio, "a turn around") is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes

place in a relatively short period of time. Its use to refer to political change dates from the scientific revolution occasioned by Copernicus' famous De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium Revolutions have occurred through human history and vary widely in terms of methods, duration, and motivating ideology. Their results include major changes in culture, economy, and socio-political institutions.

Tanzania's educational revolution

Tanzania inherited an elitism educational system but broadened it to create ample opportunities for its citizens. Most Africans were illiterate before independence, but this has been reduced to a minority of 35 percent and that number is still falling. Tanzania still plans to eradicate illiteracy, as well as ensuring full primary education to all Tanzanian children, improving the quality of education, and stressing science and technology in its schools. Access at all levels has dramatically increased since 1961. The Ugandan invasion caused massive diversions of expenditures and set back literacy campaigns and the expansion of educational opportunities. Despite this, primary education is now offered to almost every student, and secondary chances are expanding fast with the help of private schools. A growing gap between rich and poor students needs to be watched carefully, as does recurrent textbook shortages, low teacher salaries, and regional inequalities that persist. Swahili has grown in prominence since the Germans elevated it to the medium of instruction in their colonial schools. It is still the major medium of instruction at most levels of Tanzania's educational system. University populations are growing very fast, and Tanzania may soon be in a position to attract high tech industries because of the number of qualified engineers, computer programmers, and skilled workers that it is producing. Tanzania truly earned the World Bank's assessment of it as a "rising star" and a nation to watch, despite on-going problems.

Tanzania abolished tuition fees in 2002, and school attendance surged from 59% to 95% today. But growth has bought its own, unforeseen difficulties.

Enrolment at primary schools nationwide has leapt from 59% in 2000 to 95.4% today, putting the impoverished country well on course to achieve the second millennium development goal (MDG) of primary school education for all by 2015. Zainabu is living proof of an African success story. But it's not quite that simple. Campaigners say the true figure is lower than the official statistics suggest, especially in remote rural areas. They note that half of pupils will fail to qualify for secondary school, with 3,000 girls a year dropping out due to pregnancy. The progress has come with a lesson in the law of unintended consequences. Enrolment has grown so fast in Tanzania that the school system is creaking with overcrowded classrooms, shortages of books, teachers and toilets, and reports of corporal punishment being used to keep order. In short, it seems that quality has been sacrificed for quantity. Zainabu, for example, is in a class of 93, though she doesn't seem to mind. But she does have complaints: "We want food at school during the day because some of the class are too young to deal with hunger a long time. They can't concentrate on lessons." No meals are provided here at the 873-pupil Kizuiani school in Bagamoyo. Its annual intake doubled instantly when fees were abolished. There is now a ratio of more than 100 pupils per teacher and a shortage of 90 desks. New toilets were constructed with the help of ActionAid. In Tanzania, parents are still expected to contribute to teaching materials, uniforms and even classroom construction. Still, it's not enough. Mwakibinga says he has come across classes of 200 pupils where quality inevitably suffers. "What do you from expect from a classroom of 200 children, even if the teacher works like a donkey? What if the 200 children have no books?" The national teacher-pupil ratio has climbed from 1:41 in 2000 to 1:51 today. New teacher training colleges, including some in the private sector, have opened in a bid to meet the demand, but some trainees are allegedly rushed through in three or four months. The profession also suffers from low public esteem. One teacher, Florence Katabazi, 37, says: "I chose teaching and to this day people think I'm a failure. People say, 'I want my son to be a doctor or lawyer, not a teacher,' It's shameful to be a teacher. Everyone runs away from the profession. If they want to be an accountant, they just use teaching as a bridge. At the end of the day we've got 10,000 half-baked teachers and only 400 good ones." Tanzania has been reminded of the old saw: be careful what you wish for. The gap between ambition and reality is revealed by a stark statistic: the pass rate for the primary school leaving exam is just 49.4%. But

Tabitha Friday is determined to be among them. After her father died, she went to live with her aunt, and now at the age of 18 is determined to get the primary school education she never had.

EDUCATIONAL REVOLUTION IN CHINA

A natural interest in learning more about education in the People's Republic of China has grown out of the reestablishment of relationships between the United States and mainland China. This study, one of a series to help inform the American educational community about significant educational developments in other countries, provides basic background information to understanding recent developments in the educational system of mainland China. Based mainly on primary source material, the study summarizes the course of the educational revolution which was initiated in China in the spring of 1966 and provides a succinct analysis of the impact of this wide ranging upheaval on the organization and conduct of the educational enterprise in that country. Data on the number of higher education institutions of various types and universities within the Peoples Republic of China are appended. While China's remarkable economic achievements attract international attention, a less advertised revolution is quietly taking place in China's higher education system. The long-term implications of this may be much more important for China's future and the world's. A small part of it I witnessed myself. Last May I visited Xiamen University on China's southern coast, overlooking Jinmen (Quemoy) and Taiwan. Established in 1921, the university's main campus still displays early 20th century Western influences. Yet its new campus, recently built from scratch within nine months on a desolate island, definitely belongs to the 21st century. Accommodating thousands of students from all over China, the new campus contains state-of-the-art buildings, classes, labs, dormitories, offices, halls and an outstanding library with advanced equipment and technologies. The students who accompanied us were conversant in English and open-minded. Of course, it was impossible to judge quality on the basis of a few hours' visit, but this visit was a signpost pointing to the course of China's higher education revolution. To a great extent, this revolution implies a reincarnation of the Western model of the comprehensive university, abandoned in 1949 when the communists seized China. For the next 30 years, China's higher education duplicated the Soviet system, with all its advantages and disadvantages. Furthermore, as a result of the political and ideological upheavals, especially the break with the Soviet Union and the Cultural Revolution, Chinese universities decayed and even closed down for about ten yearsfrom the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. With the beginning of reforms and modernization in the

late 1970s, institutions of higher education were re-opened and revived, but remained mired in past practices. Thus, a gap gradually emerged between China's growing free-market economy and opening to the outside and the more conservative and still-secluded higher education system. The system suffered from a number of problems that included central rigid planning and control; departmentalization and barriers between teaching, research and production; narrow range of studies; small universities, duplication and overlap; too much emphasis on science and engineering; lack of academic freedom; waste and low efficiency; free tuition; limited spending and investment; and low admittance rates. To be sure, China's post-Mao reforms indirectly affected the higher education system, but reforms in higher education did not begin in earnest until the late 1990s. In 1998, CCP General Secretary and PRC President Jiang Zemin called for the establishment of 100 first-class universities and 30 world-class research universities by 2020. Right now only four Chinese universities are recognized as meeting top international standards: Beijing and Qinghua (in Beijing) and Fudan and Jiaotong (in Shanghai) (Taipei Times, September 7, 2005). Entitled the 98-5 Project, the new plan has already achieved remarkable results. To begin with, the number of higher educational institutions has almost tripled, from 598 in 1978 to 1,731 in 2004. From 1978 to 1999 the average annual increase was 20; from 2000 to 2004 it was 172. In fact, the increase is even more dramatic, as over the last few years a number of smaller universities merged into larger academic institutions (all data herein, unless otherwise noted, is from China Statistical Yearbook 2005). The overall number of full-time higher education faculty more than quadrupled, from 206,000 in 1978 to 858,000 in 2004. Again, the main growth was from 2000 to 2004: an average of 98,750 were added each year (compared to an average of 11,680 from 1978 to 1999). Also, by 2004, the overall number of students in China had reached over 21 million. The share of undergraduate students was 62.5 percent, while postgraduate students accounted for less than four percent, still quite small. Of the postgraduate students, about 20 percent were studying for a Ph.D., with the remainder as masters degree students. Another indication of this revolution is that the number of new students in the higher education system has increased over ten-fold, from about 400,000 in 1978 to nearly 4.5 million in 2004. While from 1978 to 1999 the average annual intake was 82,000, from 2000 to 2004 it was 566,750. The total number of undergraduate students has increased more then 15 times, from 856,000 in 1978 to 13.3 million in 2004. While from 1978 to 1999 the average annual increase was 213,863, from 2000 to 2004 it was nearly two million. The number of those who successfully completed their undergraduate study has also

increased by nearly 15 times, from 165,000 in 1978 to 2,391,000 in 2004. While from 1978 to 1999, the average annual increase in graduates was 35,682, from 2000 to 2004 it was 238,750. The number of new postgraduate students has dramatically increased over 30 times, from 10,708 in 1978 to 326,286 in 2004. While from 1978 to 1999 the average annual intake was over 5,000, from 2000 to 2004 it was nearly 50,000. In fact, the total number of postgraduate students in China's higher education institutions has multiplied by an amazing 75 times, from 10,934 in 1978 to 819,896 in 2004. From 1978 to 1999 the average annual increase was 13,196; from 2000 to 2004 it was 129,664. These are perhaps the most significant figures that reflect the revolution in China's higher education. Equally, the number of those who successfully completed their postgraduate study has increased from nine in 1978 to 150,777. From 1978 to 1999 the average annual increase in postgraduates was 2,671; from 2000 to 2004 it was 23,000. In 2004, the majority of China's postgraduate students have studied either engineering (38.8 percent) or science (12.5 percent); nearly 60 percent of the doctoral students and nearly 50 percent of the masters candidates study one of these subjects. In 2004, about 56,000 engineering students successfully completed their postgraduate study. About 48,000 received their masters and about 8,000 received their Ph.D.s. The percentage for undergraduate students is somewhat lower, but still impressive. Out of a total of 13.3 million students, nearly 4.4 million, one-third, study engineering. Nearly 2.3 million undergraduates (17 percent) study managementmore than three times the number of economics students. An additional 1.16 million study science and around one million study medicine. In 2004, more than one million Chinese students successfully completed their undergraduate study in engineering (over 812,000) and science (over 207,000). Evidently, China is still considerably weaker in humanities and especially in social sciences and law. As a matter of fact, the China Statistical Yearbook does not provide any data on sociology, anthropology, political science, international relations, demography, statistics or religion. History attracts 0.5 percent of all students and Philosophy 0.1 percent. Aware of this handicap, Beijing tries to promote the idea of the comprehensive university notwithstanding its sensitivity to humanities and social sciences. Yet this imbalance is also, and perhaps mainly, an outcome of the students' preference for more practicaland profitableprofessions. Another interesting change has taken place in the number of Chinese students studying abroad. Until the beginning of reforms in the late 1970s, Chinese students had mainly studied in Soviet and East European universities. With the launch of reforms in 1978, Beijing allowed and even encouraged students to travel wherever they wanted. As early as 1978, 860 students were already studying abroad, reaching a

peak of 125,179 in 2002. Then the number began to decline reaching 114,682 in 2004. Although higher education in China has become more expensive over time, it is still considerably less expensive than studying abroad. More important, this home-study trend must also reflect the students' realization that some Chinese universities are of similar quality to Western universities. Still, Chinese students have continued to go abroad in the 2000s. The annual average for 2000-2004 was 18,923, compared to 2,631 for 1978-1999. While the number of Chinese students abroad is slowly decreasing, more and more foreign students come to study in Chinese universities. In 2004, the number reached approximately 86,000, mostly from Asia, with 60 percent from South Korea and Japan. China is interested in attracting foreign students and plans to accommodate 120,000 in 2007 (The Chronicle of Higher Education, 61:9, October 22, 2004, p. A52). Once again, foreign students come to China not only because higher education is less expensive but also because its quality is improving. Although Taiwan still slights mainland China's academic institutions and degrees, the fact that they become attractive to students is causing concern in Taiwan whose universities face a growing shortage of students, or another wave of brain-drain (Taipei Times, September 7, 2005). China's revolution in higher education reflects large-scale investment. In 2004, most higher education funds came directly from the central government (nearly 47 percent) and from tuition fees (nearly 30 percent). The rest came from other organizations that included donations and fund-raisingthe share of which in the higher education budget has been growing steadily, reflecting China's remarkable economic growth and the contribution of companies, corporations and businessmen. There has also been an exceptional increase in governmental allocation for science and research that jumped over 22 times, from the equivalent of US$660 million in 1978 to US$14.6 billion dollars in 2004. Again, this was especially evident from 2000 to 2004 when the average annual increase reached 1.85 billion dollars, compared to about 300 million dollars from 1978 to 1999. This is just the beginning of China's higher education revolution, which is a long-term plan. With its huge population, Chinas plan to increase the entrance rate of the relevant age-group (19-21) from 13.3 percent in 2001 to 23 percent in 2010, to 40 percent in 2020 and to 55 percent in 2050over a four-fold increase. Correspondingly, they plan to almost triple the number of undergraduate students between 2001 and 2050 and to quadruple the number of graduates by 2020. One planned outcome is that the share of those with higher education in the workforce is due to increase almost 10 times from 4.66 percent in 2001 to 44 percent in 2050 (Chinese Education and Society, 38:4, July-August 2005, p. 14).

Impressive as they are, these quantitative changes tell very little about the quality of China's higher education. Compared to other countries, China's higher educational system has one major disadvantage and two major advantages. Its main disadvantage reflects the time-honored legacy of conformity, discouraging innovation and lack of academic freedom. As much as Beijing would invest in higher education, if it does not manage to overcome these obstacles and provide a climate for fearless academic and scientific discussion, this revolution will be short-lived. At the same time, China has two formidable advantages: one is its huge population and the other is its mobilization capacity that is not bound by democratic values. Given that the ratio of talented people in the Chinese society is about the same as in other countries (and some would say it is higher), the Chinese government can feed its higher education system with millions of talented and even exceptional students for years to come. Universities throughout the world have begun to appreciate the revolution in China's higher education and to increase their academic cooperation with China, investing in China's private universitiesa new phenomenonand forming partnerships with established Chinese universities.

Вам также может понравиться

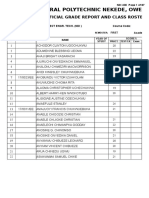

- 18e-Ee ND1 (E)Документ87 страниц18e-Ee ND1 (E)Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Teaching Outline For Special Blood of Sprinkling Service - 15.10.2021Документ1 страницаTeaching Outline For Special Blood of Sprinkling Service - 15.10.2021Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- (With SCRPTR) Covenant Day of Open Doors - 3rd .07.2022Документ2 страницы(With SCRPTR) Covenant Day of Open Doors - 3rd .07.2022Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- 2 - BYINTEK Projector 0930Документ21 страница2 - BYINTEK Projector 0930Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- EE ND2 M 1st Sem 2019Документ19 страницEE ND2 M 1st Sem 2019Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- July 2022 Sunday Service Teaching Outlines (FM)Документ2 страницыJuly 2022 Sunday Service Teaching Outlines (FM)Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- IMECS2019 MSWord TemplateДокумент6 страницIMECS2019 MSWord TemplateAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- June 2019 Sunday Teaching Outline HMДокумент2 страницыJune 2019 Sunday Teaching Outline HMAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- (David Oyedepo) Operating in The Supernatural (BookSee - Org) - 1 PDFДокумент47 страниц(David Oyedepo) Operating in The Supernatural (BookSee - Org) - 1 PDFkiran100% (9)

- Port-Harcourt Sales Report (January - June 2019) : BY: Chikezie DarlingtonДокумент27 страницPort-Harcourt Sales Report (January - June 2019) : BY: Chikezie DarlingtonAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Papa AdeboyeДокумент2 страницыPapa AdeboyeAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- EEC 123 Electrical Machine I TheoryДокумент90 страницEEC 123 Electrical Machine I TheoryVietHungCao86% (7)

- Covenant Day of FruitfulnessДокумент4 страницыCovenant Day of FruitfulnessAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Port-Harcourt Sales Report (January - June 2019) : BY: Chikezie DarlingtonДокумент27 страницPort-Harcourt Sales Report (January - June 2019) : BY: Chikezie DarlingtonAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- WITEDДокумент6 страницWITEDAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Low Cost and Effective House WiringДокумент17 страницLow Cost and Effective House WiringAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Hnd1e 2017-2018Документ43 страницыHnd1e 2017-2018Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Practical CardДокумент1 страницаPractical CardAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Sample Question On Database ManagementДокумент1 страницаSample Question On Database ManagementAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Technical Guidlines For Instrumentation RepairsДокумент38 страницTechnical Guidlines For Instrumentation RepairsAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Flowsheet Symbols and PenI Diagrams PDFДокумент30 страницFlowsheet Symbols and PenI Diagrams PDFRajeshОценок пока нет

- Transformer PDFДокумент2 страницыTransformer PDFLafin LokiОценок пока нет

- HND CodeДокумент189 страницHND CodeKrista Jackson100% (1)

- Technical Guidlines For Instrumentation RepairsДокумент38 страницTechnical Guidlines For Instrumentation RepairsAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Access 2010 Has Powerful Tools That Make It Easier To TrackДокумент16 страницAccess 2010 Has Powerful Tools That Make It Easier To TrackAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- How To Make A Simple DC MotorДокумент3 страницыHow To Make A Simple DC MotorAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- TS 112 Process and Instrument DiagramsДокумент27 страницTS 112 Process and Instrument DiagramsGeetha_jagadish30100% (1)

- LED LIGHTING Research Report AbstractДокумент14 страницLED LIGHTING Research Report AbstractAkachi Okoro0% (1)

- Analogue EEC436Документ46 страницAnalogue EEC436Akachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- Access 2010 Has Powerful Tools That Make It Easier To TrackДокумент16 страницAccess 2010 Has Powerful Tools That Make It Easier To TrackAkachi OkoroОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Doskvol AcademiaДокумент1 страницаDoskvol AcademiaAnonymous rIYNcDwlkKОценок пока нет

- Education in The PhilippinesДокумент29 страницEducation in The PhilippinesJholo SicabaloОценок пока нет

- Imperial College LondonДокумент15 страницImperial College London姜晓宇Оценок пока нет

- Main List of StudentsДокумент28 страницMain List of Studentsphone2hireОценок пока нет

- Invitation Letter For Guest LectureДокумент6 страницInvitation Letter For Guest LectureGopinath Gangadhari100% (2)

- Asian Peacebuilders Scholarship (APS) : Application RequirementsДокумент4 страницыAsian Peacebuilders Scholarship (APS) : Application RequirementsRosedian AndrianiОценок пока нет

- Art 150 Syllabus SummerДокумент4 страницыArt 150 Syllabus SummerRemnantОценок пока нет

- The Iraqi Education System Described and Compared With The Dutch SystemДокумент31 страницаThe Iraqi Education System Described and Compared With The Dutch SystemAhmad AbduladheemОценок пока нет

- Rennes School of Business FAQ 2017 2018Документ6 страницRennes School of Business FAQ 2017 2018Sri YogeshОценок пока нет

- Official TranscriptДокумент4 страницыOfficial Transcriptapi-365469575Оценок пока нет

- Surendranath College: Based On Their Position in The Provisional Merit ListДокумент1 страницаSurendranath College: Based On Their Position in The Provisional Merit ListSubhajit DasОценок пока нет

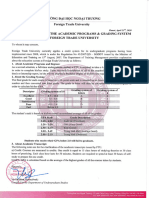

- Giải thích hệ thống điểmДокумент1 страницаGiải thích hệ thống điểmShare Tai LieuОценок пока нет

- Metrobank Foundation, Inc.-Pacific Paint (Boysen) Philippines, Inc. College Scholarship ProgramДокумент2 страницыMetrobank Foundation, Inc.-Pacific Paint (Boysen) Philippines, Inc. College Scholarship ProgramJR CaberteОценок пока нет

- UT Dallas Syllabus For mkt6310.501.07f Taught by Abhijit Biswas (Axb019100)Документ6 страницUT Dallas Syllabus For mkt6310.501.07f Taught by Abhijit Biswas (Axb019100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupОценок пока нет

- Jennifer Migliozzi Resume George WashingtonДокумент2 страницыJennifer Migliozzi Resume George Washingtonapi-284598914Оценок пока нет

- FYBA. Unit 8 Professional Ethics PDFДокумент9 страницFYBA. Unit 8 Professional Ethics PDFsrshelkeОценок пока нет

- Miami University (Viewbook)Документ9 страницMiami University (Viewbook)LancelotОценок пока нет

- "Anti-Lock Braking System ": Seminar Report OnДокумент6 страниц"Anti-Lock Braking System ": Seminar Report OnVaibhav KaleОценок пока нет

- RESUME, Sharad PaudyalДокумент2 страницыRESUME, Sharad PaudyalSharad PaudyalОценок пока нет

- Fellowship TimelineДокумент3 страницыFellowship TimelineAustin YangОценок пока нет

- Front PageДокумент5 страницFront PageSalman RazaОценок пока нет

- Law School Application RequirementsДокумент4 страницыLaw School Application RequirementsGuian LimОценок пока нет

- Martial Arts Studies Journal Issue 1Документ112 страницMartial Arts Studies Journal Issue 1Antonio Bruno100% (1)

- GCU Lahore: Information CatalogueДокумент9 страницGCU Lahore: Information CataloguenziiiОценок пока нет

- Aolkeki Memorial Scholarship: Bil Ty: ManipurДокумент5 страницAolkeki Memorial Scholarship: Bil Ty: ManipurKhizar MansooriОценок пока нет

- BEEDДокумент1 страницаBEEDNavi EscabalОценок пока нет

- MSC MBA Prospectus Final Autumn-2020 PDFДокумент47 страницMSC MBA Prospectus Final Autumn-2020 PDFMuhammad AyazОценок пока нет

- Education: Degree Subjects Institution Division YearДокумент3 страницыEducation: Degree Subjects Institution Division YearUsman MalikОценок пока нет

- MOED7013 (1) Development of Curriculum and Instruction.Документ34 страницыMOED7013 (1) Development of Curriculum and Instruction.庞超然Оценок пока нет

- AUST CV Application Form EnglishДокумент3 страницыAUST CV Application Form EnglishcateОценок пока нет