Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ECRR Peter Wilson Lecture. Professor John Beddington CMG FRS Global Challenges in A Changing World. 17 February 2009

Загружено:

The Royal Society of EdinburghОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ECRR Peter Wilson Lecture. Professor John Beddington CMG FRS Global Challenges in A Changing World. 17 February 2009

Загружено:

The Royal Society of EdinburghАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

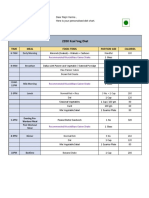

The Royal Society of Edinburgh ECRR Peter Wilson Lecture Professor John Beddington CMG FRS Global Challenges

in a Changing World

Report by Peter Barr 17 February 2009

Science to the rescue

Professor John Beddington, Chief Scientific Adviser to HM Government and Head of the Government Office for Science, believes that science and technology must play a critical role in tackling the many global challenges facing humanity through the 21st century and that the economic downturn is no time to be taking our foot off the accelerator for the investments required Listening to Professor Beddington set out these challenges, you may be forgiven for thinking the future is cancelled. He presents a stark picture of complex, interacting problems, and of transformational changes to be managed alongside these. World population is expected to rise from six billion at the start of the century to nine billion by 2050 an increase of six million people per month, mostly in developing countries. Urbanisation will accelerate. Last year, urban population overtook rural. More than a billion people live on less than 50p a day. Demand for food is projected to increase by 50% by 2030, according to the United Nations. World grain reserves are at an all-time low of 14%, down from 35% in 1986, and 75% of the major marine fish stocks are either depleted, overexploited or being fished at their biological limit. Demand for energy is projected to increase by 45% by 2030 in a business as usual scenario. Demand for water may increase by 30% by 2030. One in three people already face serious shortages in the form of physical or economic water scarcity, potentially forcing more countries to introduce charges and with the possibility of increased tensions and conflicts. The acidity of the oceans is accelerating, with Ph expected to drop by approximately 0.4 by the end of the century, due to rising CO2 emissions. Economic migration has increased from less than 80 million in 1960 to around 200 million by 2005. The worlds mega deltas are particularly vulnerable to climate change, and every year there is already around a 75% chance of one of the worlds major 136 port cities being inundated with a one-in-a-hundred-year flood.

Even some of the good news is bad. Beddington highlighted recent research which suggests that banning aerosols may have led to an increase in deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, due to an increase in droughts.

He explained too how economic growth projected for the developing world, lifting millions from poverty, would at the same time increase exponentially the demand for energy, water, food and other resources. More prosperous populations, centred increasingly in mega-cities and aspiring to the lifestyles of affluent Western nations, will require servicing, often by a rural community declining in at least relative terms. Looming over all of this is climate change and other unpredictable phenomena such as terrorism and natural disasters. Its no good having a healthy economy if the planet is killing itself for example, a 5C increase in temperature would cause a catastrophic rise in sea levels and devastate agricultural production. Unfortunately, some of our most pessimistic forecasts may not be pessimistic enough, said Beddington. For example, even the worse-case scenario for the rate of Arctic melting turned out to be not as bad as actual observations. Further research and data will be key to understanding whether short term fluctuations or more fundamental trend factors are the cause. In many areas the full impact of the changes being experienced or which are predicted, such as rising sea temperatures, is still not well understood by scientists. Whilst spending much of his RSE lecture describing the problems, Beddington talked too about solutions. He remains optimistic that science and technology can rise to the challenge, if we have the political will and invest adequately in research and in its effective exploitation. An economic downturn may not seem the best time to argue for increased investment, but Beddington believes that there are profits to be made from the crisis, and that we have no other choice. Beddington welcomed the inauguration of President Obama, because the new administration is already taking climate change more seriously, including the appointment of two Nobel Prize winners with an interest in climate change to the team of scientific advisors. Our prospects may look bleak, but Beddington seems to agree with the idea that every crisis means an opportunity. And he is very clear what this will mean: We need significant investment in science and engineering solutions to complex interrelated issues. For example, the developing world will inevitably use its massive coal reserves to generate energy, but new carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies will not only help cut emissions but also mean profits for the companies who successfully develop and market their solutions. And cleaner electricity and transport are two of the most critical issues. Reducing emissions by 80% by 2050 in the UK may seem an impossible challenge, but Beddington is confident we can reach our targets by using smart science and technology, especially if there are strong international agreements. Beddington compared a range of solutions in terms of cost benefits, suggesting that some technologies and policies are more cost-effective at reducing emissions than others. For example, better home insulation would be the cheapest and highestimpact solution, since households alone contribute about 45% to total emissions. Nuclear energy is another no-brainer for Beddington, who described it as breakeven in terms of return on investment, whilst other options such as sugar-cane biofuels generate savings. CCS is still an unproven solution which appears more expensive at the moment, but Beddington believes that it will play a crucial role in substantially lowering emissions from coal in the decades to come. For many

promising technologies, a medium to long term view of the value of investments is needed. Other positive options are re-forestation, combined heat and power plants, biomass and other renewables such as wave, wind and tidal power. To promote these solutions, we dont just need money and technological innovation but also behavioural changes, said Beddington, helped by incentives. Carbon trading may work at a national level, but individuals need more persuasion. Increasing food production by 50% in the next 30 years, at the same time as reducing agricultural energy and water consumption and managing pesticides and fertilisers more sparingly, may seem impossible, but there are grounds for hope. Grain reserves are so low that our total reserves are literally at sea at any given moment. But if we could eliminate crop losses and other wastage through the food chain, food production and food security could increase substantially, even on less land with fewer resources. At the same time, Beddington sees genetically modified crops as another key technology option with the potential to make a significant contribution. Similarly, better water management, such as recycling grey water and improving irrigation using new technologies (including nanotechnology), may mitigate the worst effects of future shortages. Some ideas, such as fertilising clouds and giant sun shades orbiting the Earth, may seem like pie in the sky, but Beddington has great hopes for fusion power and other breakthrough concepts; for instance, growing algae to increase absorption of carbon dioxide. He saw an important role too for climate models, to improve progressively our understanding of future climates. He noted at the same time the difficulties in interpreting such models, which, he explained, are inherently chaotic. Even tiny changes in inputs can lead to dramatic variations in results. The models also currently leave major uncertainties, including potential impacts on monsoons and El Nino phenomena. Dwelling for a moment on a more administrative aspect of his role, Beddington revealed that every government department has a chief scientific advisor, with the exception of the Treasury. Just as with the changing economic climate however, there are no quick fixes with science. Asked about birth control, for example, Beddington described how rapid changes in population can have a negative effect on an economy while many religions oppose contraception completely. Rather than legislating for the bedroom, societies are better off educating women, said Beddington. When it comes to climate change and other global problems, what we need is a much more holistic approach, including better communication and engagement with people. Finally, asked if it would be madness to reduce our investment in science and technology, despite the financial constraints of the credit crunch, Beddington answered resoundingly: Yes!

Opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the RSE, nor of its Fellows The Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotlands National Academy, is Scottish Charity No. SC000470

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Cultures of Apes and Other AnimalsДокумент4 страницыThe Cultures of Apes and Other AnimalsThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Enlightening The Constitutional DebateДокумент128 страницEnlightening The Constitutional DebateThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- RURAL AFFAIRS AND ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH STRATEGY FOR 2016-2021: A Response To The Scottish Government's ConsultationДокумент8 страницRURAL AFFAIRS AND ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH STRATEGY FOR 2016-2021: A Response To The Scottish Government's ConsultationThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- BBC Trust Consultation On Draft Guidelines For The Coverage of The Referendum On Independence For ScotlandДокумент2 страницыBBC Trust Consultation On Draft Guidelines For The Coverage of The Referendum On Independence For ScotlandThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Science and Higher EducationДокумент8 страницScience and Higher EducationThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Enlightening The Constitutional DebateДокумент128 страницEnlightening The Constitutional DebateThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Currency Banking and Tax Jan 2014Документ8 страницCurrency Banking and Tax Jan 2014The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Summary of DebatesДокумент4 страницыSummary of DebatesThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Scotlands Referendum Britains FutureДокумент8 страницScotlands Referendum Britains FutureThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- Welfare and Public ServicesДокумент8 страницWelfare and Public ServicesThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee Inquiry Into Scotland's Economic Future Post-2014Документ8 страницEconomy, Energy and Tourism Committee Inquiry Into Scotland's Economic Future Post-2014The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- AP14 - 03scotland's Educational and Cultural Future: A Response To The Scottish Parliament's Education and Culture CommitteeДокумент4 страницыAP14 - 03scotland's Educational and Cultural Future: A Response To The Scottish Parliament's Education and Culture CommitteeThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Our Hidden Geology and Geomorphology: Sea Bed Mapping in The 21st CenturyДокумент8 страницOur Hidden Geology and Geomorphology: Sea Bed Mapping in The 21st CenturyThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Food Scotland BillДокумент2 страницыThe Food Scotland BillThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Energy, Entropy and The Human Enterprise.Документ4 страницыEnergy, Entropy and The Human Enterprise.The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Lost at Sea The Atlantic Salmon's OdysseyДокумент5 страницLost at Sea The Atlantic Salmon's OdysseyThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Your Face Your IdentityДокумент3 страницыYour Face Your IdentityThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Tsunami Hazard - Learning From Recent EventsДокумент3 страницыTsunami Hazard - Learning From Recent EventsThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- MacCormick Lecture 2013. Mary McAleese. The Good Friday Agreement Fifteen Years On.Документ4 страницыMacCormick Lecture 2013. Mary McAleese. The Good Friday Agreement Fifteen Years On.The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- BBC Trust Service Review On News and Current AffairsДокумент2 страницыBBC Trust Service Review On News and Current AffairsThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- An Evening With Rowan WilliamsДокумент5 страницAn Evening With Rowan WilliamsThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Welfare and Public ServicesДокумент8 страницWelfare and Public ServicesThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Women, Work and Care: A Challenge For The 21st CenturyДокумент4 страницыWomen, Work and Care: A Challenge For The 21st CenturyThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Edinburgh 300 Cradle of ChemistryДокумент16 страницEdinburgh 300 Cradle of ChemistryThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Spreading The Benefits of Digital Participation - Interim ReportДокумент68 страницSpreading The Benefits of Digital Participation - Interim ReportThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Borders, Immigration and CitizenshipДокумент8 страницBorders, Immigration and CitizenshipThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Future of Scotland's BiodiversityДокумент4 страницыThe Future of Scotland's BiodiversityThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Scotland's National Marine PlanДокумент8 страницScotland's National Marine PlanThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Womens Reproductive HealthДокумент56 страницWomens Reproductive HealthThe Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Review of Sessions 2008-2009 and 2009-2010Документ511 страницReview of Sessions 2008-2009 and 2009-2010The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Soal Uas B Inggris Kelas 3 SD Semester 2 Dan Kunci JawabanpdfДокумент5 страницSoal Uas B Inggris Kelas 3 SD Semester 2 Dan Kunci JawabanpdfPipi OhitsujizaОценок пока нет

- Giving Directions 1. Look at The Map and Answer The QuestionsДокумент2 страницыGiving Directions 1. Look at The Map and Answer The QuestionsAnonymous Q21YDaSfОценок пока нет

- BritanniaДокумент5 страницBritanniaakanksha1314Оценок пока нет

- Middlebay Corporation Case StudyДокумент4 страницыMiddlebay Corporation Case StudyVince KechОценок пока нет

- New Coke Market BlunderДокумент8 страницNew Coke Market BlunderAnkit KumarОценок пока нет

- Conjunctions Prep Adv As ConnectorsДокумент14 страницConjunctions Prep Adv As Connectorsapi-2521904180% (1)

- AppositiveДокумент5 страницAppositiveBethel SuryaОценок пока нет

- Spondias Mombin: Anacardiaceae LДокумент5 страницSpondias Mombin: Anacardiaceae LMaria José PradoОценок пока нет

- Black Order Reunion PartyДокумент31 страницаBlack Order Reunion PartyCarlotta Charlie MarinoОценок пока нет

- The Digestive SystemДокумент2 страницыThe Digestive SystemAutumn GarofolaОценок пока нет

- B ING Ujian SMK Xi Semester2Документ6 страницB ING Ujian SMK Xi Semester2Lesly MalondaОценок пока нет

- Alternative Sources of Rennet for CheesemakingДокумент2 страницыAlternative Sources of Rennet for CheesemakingZyla Monica JavierОценок пока нет

- HACCPДокумент47 страницHACCPSujit Shandilya100% (1)

- Genchem KJДокумент3 страницыGenchem KJKheren D. PenidesОценок пока нет

- Rajni Verma's Diet PlanДокумент2 страницыRajni Verma's Diet PlanPiyushОценок пока нет

- Afa 1 Module 5 ActivitiesДокумент6 страницAfa 1 Module 5 ActivitiesJulius Balbin100% (2)

- Gbio 121 Week 11 19 by KuyajovertДокумент11 страницGbio 121 Week 11 19 by KuyajovertAnonymous DZY4MvzkuОценок пока нет

- Alma Matias ResumeДокумент2 страницыAlma Matias Resumeapi-339177758Оценок пока нет

- Write The Plural of The Following Nouns.: Write The Correct Pronoun According To The SentenceДокумент5 страницWrite The Plural of The Following Nouns.: Write The Correct Pronoun According To The SentenceHenry Arias SolizОценок пока нет

- L2 Happy New YearДокумент23 страницыL2 Happy New YearJulioОценок пока нет

- DMir - 1912 - 05!25!001-A Ultima ChamadaДокумент16 страницDMir - 1912 - 05!25!001-A Ultima ChamadaTitanicwareОценок пока нет

- CLASSIFYING CARBS AND NUTRIENTS FOR ENERGY AND HEALTHДокумент52 страницыCLASSIFYING CARBS AND NUTRIENTS FOR ENERGY AND HEALTHAnna SantosОценок пока нет

- Water Buffalo FAOДокумент321 страницаWater Buffalo FAOAndre BroesОценок пока нет

- Case Study Brooklyn Children's Museum 4Документ11 страницCase Study Brooklyn Children's Museum 4ไข่มุก กาญจน์Оценок пока нет

- Activity - BHEL: Swami ShreejiДокумент2 страницыActivity - BHEL: Swami ShreejiANAnD PatelОценок пока нет

- Blue Economy and ShipbreakingДокумент8 страницBlue Economy and ShipbreakingAdeen TariqОценок пока нет

- Porter's Five Force ModelДокумент20 страницPorter's Five Force Modelamitgarg46Оценок пока нет

- English 6 LPДокумент25 страницEnglish 6 LPGlenn Mar DomingoОценок пока нет

- The Complete Crafter - GM BinderДокумент26 страницThe Complete Crafter - GM BinderPhạm Quang0% (1)

- What Are Polysaccharides How To ClassifyДокумент6 страницWhat Are Polysaccharides How To ClassifyBiochemistry DenОценок пока нет

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingОт EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingОт EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (33)

- Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandОт EverandChesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (38)

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanОт EverandThe Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite CrustaceanОценок пока нет

- The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceОт EverandThe Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (11)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorОт EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (137)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseОт EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (69)