Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Mouthpieces and The Working Saxophonist

Загружено:

Lester SimonИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Mouthpieces and The Working Saxophonist

Загружено:

Lester SimonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Mouthpieces and the Working Saxophonist

By Paul Navidad Beginning in 1998, after attending a couple of saxophone masterclasses, I became convinced-or rather, obsessed-with finding one mouthpiece for each horn, to play every style I needed (with the exception of classical, of course). Sounds like your every day, garden-variety saxophone player, right?! Well, at the time, I was a year out of graduate school, and quite the gigging fool (or as my friend Scott Strecker termed it, "musical whore"), playing any and every style that was thrown at me. I was playing in a band at a major theme park during the day, and doing all sorts of casual, corporate, club, and recording dates at night, many times never knowing what style I would be playing next, until the "leader du jour" started the next tune on the bandstand. I had no time to think about what mouthpiece would work for each style; I just needed something that was flexible enough to cover the gamut. In one masterclass, Brandon Fields gave a presentation that left a lasting impression on me. One of the main things I left with was a new philosophy about mouthpieces-a purist one at that. Simply put: round chamber, little to no baffle. Translation: hard rubber Meyer for alto, metal Otto Link for tenor.

The Mouthpiece Chamber

Someone once told me a story about mouthpiece maker Ralph Morgan, who was working for Selmer when the C* 80 came out. For those of you who don't know, the C* 80 has a square chamber. Apparently, he caused quite a stir when he asked, "When are you going to make the saxophone square?" In his own sarcastic way, Morgan makes an important point, after all, can you really put a square peg in a round hole? Think about how the airstream is physically affected by moving from a non-round chamber into a conical pipe. I'm not going to get into details the physics of the situation, because I'm sure most of you can see the logic involved. For years in school, I played primarily horseshoe-shaped chambers (Rousseau 4R, Rousseau NC-4), and used square chambers for commercial work (Yanigasawa silver-plated). I was never satisfied, because there was always some kind of inconsistency in tone, pitch, or some other parameter. There was a slight adjustment period when I made the decision to go to round chambers for everything, but once I made the change, I was much happier. I was able to blow effortlessly, without having to manipulate to get things to work. I was able to play with "one airstream," as my mentor, Leo Potts had tried to instill in me years before. The fundamentals of my playing became very pure. One thing that I've noticed about mouthpieces with a round chamber and little to no baffle is the only way they will work properly is if you are playing the saxophone correctly. So many new mouthpieces today are so "hot-rodded" for certain tonal qualities, ease of altissimo, etc., that they actually hide a lot of the faults in our playing. But put an Otto Link on your tenor, and there's nowhere to hide. If you aren't playing the horn correctly, everyone will know. Interestingly, I found out after a year of playing my Link, when I popped my Yanigasawa (square chamber) back on just for grins, I was finally able to play it properly. Compare chambers for yourself. There are lots of interesting ones out there in addition to the conventional designs (for a time, I played the Rousseau Metal Jazz mouthpiece which has an inverse trapezoidal chamber). Go into your local music store or saxophone pro shop and spend a few hours blowing through a variety of mouthpieces. If you can, bring a friend to be your sound consultant. If you are unable to find someone to go with you, solicit opinions from others in the shop, or bring some kind of recording device. Take notes on the differences in feel and sound between chambers. You will notice differences in back pressure up and down the horn, pitch variances, control issues, etc.

The Mouthpiece Baffle

As I began venturing back into the world of contemporary jazz, I began to realize that my all-purpose setups would not be ideal for use in an entire evening of fusion, funk, or other styles that put a high demand on the altissimo register. Almost everyone I consulted recommended that I switch to a mouthpiece with some kind of medium to high baffle. While I was determined to make my all-purpose set-ups work, I realized I was fighting a losing battle and began both trying out mouthpieces with all sorts of baffles. Some of you may be wondering what a baffle does. Quite simply what happens is the higher the baffle, the smaller the space just inside the tip opening. The result is an increased speed in the air entering the chamber. Typically this results in a brighter sound, and it can ease the production of altissimo pitches. On the down side, it can affect intonation for the worse, and thin out the tone. I started with short baffles that had a sharp drop off. A friend of mine even constructed a few for one of my tenor Links. While this type of baffle moved my sound in the direction I was looking at going-brighter with more edge-I didn't like the fact that my sound was markedly thinner, pitch-specifically in the upper and altissimo registers-was squirrelly, and altissimo control was inconsistent. I moved on to roll-over baffles next, and for a while I thought that they were a panacea for me. This didn't last long, as I noticed that pitch in the upper and altissimo registers was still a little squirrelly. I tried the Jody Jazz DV mouthpiece on tenor, a relatively high baffle with a straight drop off in a "V" shape into a large chamber. I was intrigued by it because it didn't necessarily feel as if there was a baffle in the mouthpiece, however, I wasn't able to get the altissimo control I sought. At this point, I gave up on baffled mouthpieces, and instead thought I could solve my problem by putting a Rico Plasticover on my alto Meyer. It didn't have the feel and control I was looking for, but I decided to deal with it. This set-up had a good sound and decent control. On tenor, I switched from my Link to a vintage pre-Hollywood Dukoff which had a big, ballsy sound, and had acceptable altissimo control. The occasional use of a Plasticover worked on this piece as well.

Mouthpieces and the Working Saxophonist

Part II - Mouthpieces for Specific Situations

By Paul Navidad

Consistency in Your Sax Set-ups

I had resigned myself to using my all-purpose set-ups for contemporary gigs, and was content to do so until the 2005 NAMM Show . . . I was hanging out at the Keilwerth exhibit with saxophonists Greg Vail and Wayne Mestas. Greg is wellknown in the contemporary jazz community, having played several years with the group Kilauea. Both Greg and I were trying out alto saxes, and passing them back and forth. I played on a black nickel horn, and felt I sounded good . . . that is, until I passed it to Greg and heard his sound. I realized that Greg's sound was far better suited for the contemporary arena than mine, and that I needed to find a set-up that would work for me on contemporary gigs. The great mouthpiece search was back on again. What ended up working was a long low-to-medium baffle that didn't have the appearance of a wedge, but ran the length from the tip to the chamber. It was a Beechlerbellite #7, the old fusion standby which virtually every contemporary alto player was using in the late 1980s (in fact, I purchased it in 1989). Granted, it's a very genre-specific mouthpiece, so I choose to only use it for contemporary work. However, the Meyer still serves as my all-purpose set-up, and I am able to switch between the two

mouthpieces easily. Solving the contemporary question on tenor is still an issue, however I've reached a temporary solution. My vintage Dukoff is great if I am playing an entire night of acoustic straight ahead, and can even work in a concert band or saxophone quartet context, where a dark sound is preferred, since it has no baffle. On a casual, it's a decent all-purpose set-up, and can cut the contemporary material, provided that I have a microphone. But it just doesn't do it for an entire contemporary gig. Since I was playing the Beechler on alto, I thought, "Why not play one on tenor too?" Sounds logical, right? Unfortunately, the tenor metal Beechler cut like a laser, and even the darkest sounding reed wasn't enough to tame the beast. I flew to St. Kitts in the Caribbean for a gig, and it was extremely humid. Knowing that the climate would be a factor, I brought a variety mouthpieces, reeds, and ligatures. I had some considerable down time prior to sound check to experiment. I ended up selecting a Guardala laser-trimmed Crescent (low baffle that looks like a skateboard ramp, round chamber) with Rico Plasticover reeds. It did the trick, but I ended up sacrificing the tonal spectrum in the process-the sound was very mid-rangey (lacking in lows and highs). Fortunately for me, this setup worked even better once I got back to Southern California. Again, this set-up has some similarities in feel to my vintage Dukoff, and I am able to switch between the two mouthpieces relatively easy. Moreover, this makes it comfortable to switch between alto and tenor on the same gig.

Improving Your Set-up: Selecting the Right Reed and Ligature

So what happens when you have a mouthpiece that you like for the most part, but doesn't feel totally dialed-in? Typically, I will go into a music store and pick up two of every reed model in stock and experiment. I will consult other musicians-not necessarily saxophone players-and collect opinions as to my sound. I may even record myself. Once I have selected the optimal reed, then I will experiment with different ligatures. I have a number of ligatures at home, and am pretty familiar with what each does. If the mouthpiece needs taming (i.e. the harmonics are out of control), I will use a ligature that compresses the harmonic spectrum (similar to rolling off the low and high frequencies with a graphic equalizer) such as a Rovner or Olegature. I'm not particularly fond of Rovners as they tend to deaden the resonance of the mouthpiece a bit too much, but sometimes you need that to tame a particularly bright mouthpiece. In contrast, if I need my sound to have more brilliance, then I will use a more vibrant ligature such as a Brancher or Selmer. What I like best about the Brancher is that there is very little contact with the mouthpiece, thus allowing more of the mouthpiece to vibrate. There are plenty of ligatures that fall in between, and it just depends on your preference on if you desire more control or more resonance. Other ligatures that you may want to try include the Winslow (out of production, but you can still find them), the Francois Louis Ultimate Ligature, the various models of BG, and the Bonade. Some players are fortunate to find something they like (or at least something with which they are willing to work) and use it their whole lives. For many of us however, who have to work in a multitude of capacities, the setup may be ever changing. If you can at least find a variety of equipment that is consistent and similar, you will be able to move between setups with relative ease. Best of luck to you on your journey.

by Paul Navidad

Paul Navidad is active as a freelance professional musician in Southern California, but his work has taken him all over the world. He holds a Masters in Music degree with a concentration in Saxophone Performance/Jazz Studies from California State University, Long Beach. Some of his performance and recording credits include Perry Farrell, Deborah Harry, Isaac Hayes, Al Jarreau, Dave Koz, Lisa Loeb, and Lou Rawls. He has also recorded on numerous film and television soundtracks. Paul currently serves as the Director of Jazz and Commercial Music Studies at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, California. For more information on Paul Navidad, you can visit his website at www.PaulNavidad.com.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hairspray Script - RevisedДокумент8 страницHairspray Script - RevisedMariejo Gabuyo0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Something's Afoot Tig2Документ37 страницSomething's Afoot Tig2AlcindorLeadon50% (2)

- One Second and A Million Miles - The Bridges of Madison - County - JRBДокумент4 страницыOne Second and A Million Miles - The Bridges of Madison - County - JRBKFarnum Jr.0% (6)

- Saxophone History TimelineДокумент12 страницSaxophone History TimelineDaniel Cardona GiraldoОценок пока нет

- Composers Romantic Period: of TheДокумент22 страницыComposers Romantic Period: of TheAnalyn QueroОценок пока нет

- Ishmonbrownresume 2019Документ1 страницаIshmonbrownresume 2019api-233713154Оценок пока нет

- Piano AbendДокумент2 страницыPiano AbendAliYildirim100% (1)

- Newsday Pulitzer Prize WinnersДокумент42 страницыNewsday Pulitzer Prize WinnersNewsdayОценок пока нет

- Evan CraftДокумент4 страницыEvan CraftLisandra100% (1)

- Abdullah IbrahimДокумент9 страницAbdullah IbrahimhbОценок пока нет

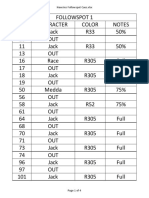

- Newsies Followspot CuesДокумент4 страницыNewsies Followspot Cuesapi-319390606Оценок пока нет

- Corcovado: Am6 G O7 ( 13) Gm7 C9Документ1 страницаCorcovado: Am6 G O7 ( 13) Gm7 C9Bruno Garotic100% (1)

- Sound ConceptsДокумент4 страницыSound Conceptsapi-201119152Оценок пока нет

- John Coltrane DevelopmentДокумент50 страницJohn Coltrane Developmentr-c-a-d100% (4)

- History of BalletДокумент6 страницHistory of BalletNexer Aguillon100% (1)

- List of Organisations Covered by Regional Office-Kolar (As On 30.09.2014) (F-Register)Документ284 страницыList of Organisations Covered by Regional Office-Kolar (As On 30.09.2014) (F-Register)mutton moonswamiОценок пока нет

- Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura The Associates of Sri CaitanyaДокумент5 страницBhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura The Associates of Sri CaitanyaJSKОценок пока нет

- Mr. CellophaneДокумент3 страницыMr. CellophaneQuinto Seccion AОценок пока нет

- A Guide To George Benjamin's Music - Music - The GuardianДокумент3 страницыA Guide To George Benjamin's Music - Music - The GuardianEtnoОценок пока нет

- 150 Most Common Regular VerbsДокумент4 страницы150 Most Common Regular VerbsyairherreraОценок пока нет

- Manuscritoa 133 - 21 - 3 EngДокумент17 страницManuscritoa 133 - 21 - 3 EngSergio Cuba100% (1)

- Garrido-Lecca, C. - Danzas Populares Andinas (Vln. & Pno.) - Sample - 10.30.14Документ6 страницGarrido-Lecca, C. - Danzas Populares Andinas (Vln. & Pno.) - Sample - 10.30.14Jesus Surco0% (2)

- Families of Musical InstrumentsДокумент8 страницFamilies of Musical InstrumentsEdgar Soller Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Comp. of PharynxДокумент10 страницComp. of PharynxrairochadelОценок пока нет

- Vienna - Society On Music Making - Ella NagyДокумент4 страницыVienna - Society On Music Making - Ella NagyPedro Lopez LopezОценок пока нет

- History of Modern DanceДокумент2 страницыHistory of Modern DanceAronAbadillaОценок пока нет

- The Jazz Essays of Theodor Adorno: Some Thoughts On Jazz Reception in Weimar GermanyДокумент26 страницThe Jazz Essays of Theodor Adorno: Some Thoughts On Jazz Reception in Weimar GermanyAnonymous WQumjQОценок пока нет

- History of Belly DanceДокумент2 страницыHistory of Belly Danceapi-250981588Оценок пока нет

- The Compositional Language of Kenny WheelerДокумент85 страницThe Compositional Language of Kenny Wheelergabitocortazar100% (4)

- Carnatic MusicДокумент59 страницCarnatic MusicPradeepKumarОценок пока нет