Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Warren E Buffett 2008 Case

Загружено:

Anuj Kumar GuptaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Warren E Buffett 2008 Case

Загружено:

Anuj Kumar GuptaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

WARREN E BUFFETT, 2008 Yiorgos Allayannis Warren Buffett, the legendary Omaha based investor, acted quickly on January

23, 2008, when his company Berkshire Hathaway Inc., bought a 3% stake in the Swiss reinsurance giant Swiss Re. In addition, Berkshire Hathaway purchased a 20% stake in Swiss Res property and casualty exposure over the next five years.1 On the one hand, some analysts saw this action by the Oracle of Omaha as a signal to move quickly in a sector (financials) and a company (Swiss Re) that, though beaten down, might present a substantial opportunity (Exhibit 1). On the other hand, some analysts were surprised that Buffett invested in Swiss Re, given his earlier investment in General Re, one of Swiss Res competitors. They were also surprised by the investment in Swiss Res property and casualty business in light of the soft pricing cycle that the sector was currently in.2 For Swiss Re, this move clearly meant support for its capital, as the company intended to continue its stock buyback program in fact, after the deal was announced, Swiss Re declared a (Swiss francs) CHF 1.75 billion (USD 1.6 billion) stock buyback, on top of a CHF 6 billion buyback the year before (with CHF 2.7 billion of that amount already repurchased). Referring to Berkshires investment, Jacques Aigrain, Swiss Res CEO, noted, They have full freedom to buy or sell as they wish. We are extremely proud to have them as shareholders.3 Although Swiss Res stock soared 10% following the announcement, it had subsided by the end of the trading day, closing up only 3.7%. By his own admission, Warren Buffett had been lollygagging around, unable to find good investment opportunities for his almost USD 50 billion in cash during the past year or so.4 He had gotten back into the market the previous month, spending USD 6 billion to acquire NRG, a Dutch insurer, and 60% of Marmon, a holding company that had a variety of industrial segments, including a company manufacturing rail cars. Marmon was owned by Chicagos well known Pritzker family, and the sale allowed some family members to monetize their investments and diversify. These recent acquisitions notwithstanding, a large amount of Berkshire Hathaways cash was dormant, earning little compared with what investors had come to expect from Warren Buffett and his company. If he could not find an attractive opportunity, the cash would continue to sit idle, earning subpar returns. But Buffett was famous both for his patience and his ability to make a quick move at the most auspicious moment. The Swiss Re deal was thus characteristic of Buffetts investments. Yet now that success had brought him ample capital, he faced the problem of putting capital to work. It was not unlike the problem faced by many large corporations: how to control and manage growth. Although not entirely new to him, the challenge had never been more complex. And critics were quick to question whether a stake in Swiss Re would significantly help 1 Haig Simonian and Francesco Guerrera, Buffett Move Boosts Swiss Re, Financial Times, 24 Jan 2008 2 Judy Greenwald, Berkshire Buys Stake in Swiss Re, Business Insurance, 28 Jan 2008 3 Simonian and Guerrera, Buffett Move Boosts Swiss Re 4 Francesco Guerrera, Lollygagging Ends with Classic Buffett Deal, Financial Times, 24 Jan 2008

Buffett continue his 30 year winning streak. Considering the changes taking place in the world around him, would he be better served by abandoning his customary practice of value investing, as exemplified by his purchase of Swiss Re, and pursuing growth in other ways? Despite Buffetts apparent desire to uphold his traditional investment strategies, Berkshire Hathaway would inevitably change, and for distinctly organic reasons. In Berkshires 2006 Annual Report, Buffett essentially ran an ad for a candidate to succeed me as Berkshires chief investment officer when the need for someone to do that arises, adding, I feel terrific, and according to all measurable indicators, am in excellent health. Not quite attributing this state of affairs to his infamous diet, he joked, Its amazing what Cherry Coke and hamburgers will do for a fellow. The right person would be genetically programmed to avoid serious risks, including those never before encountered. Other talents would include independent thinking, emotional stability, and a keen understanding of both human and institutional behavior. The successful candidate would then conduct a study of Buffett and Berkshire and be ready to takeover should anything happen.5 Recent Investment Moves In April 2007, Buffett made what was thought to be his first investment in railroads, buying a 10% stake in Burlington Northern Santa Fe. The investment was widely believed to have been motivated by a marked global increase in energy demand. Railroads provided a cleaner way to transport commodities than did trucks, and thus stood to benefit from any growth in energy demand. What was surprising about this investment was that, unlike many of Buffetts investments in fundamentally good stocks that had been beaten down for one reason or another, Burlington Northern seemed to have been on the upswing, trading in the high 80s from the low 50s two years earlier, in April 2005. In late December 2007, in the midst of the sub-prime mortgage crisis, Buffett announced a small investment of USD 105 million to fund Berkshire Hathaway Assurance Corporation (BHAC), a start up bond insurance company that would insure bonds issued by cities, counties, and states to finance schools, roads, and other public projects. The public was largely unfamiliar with this old and somewhat mysterious sector of public financing, whereby states, cities and counties often financed public works projects through the issuance of bonds. Demand for these bonds tended not to be as high as that for bonds of publicly traded corporations because investors worried about the possibility of default in the public sector, which was significantly less transparent than publicly traded corporations. In order to assuage these fears of default risk in public entities, bond insurers needed capital (of which Buffett had plenty) and a stellar credit rating (AAA), which BHAC was also expected to have. Nevertheless, BHAC faced many risks, including transparency issues and the possibility that public entities would overspend and Berkshire would have to foot the bill (a moral hazard problem). Buffett had taken a wait and see approach with the new business, seeding it with initial capital that would allow it to underwrite potentially around USD 16 billion in new business under moderate

5 Berkshire Hathaway, Annual Report (2006); Carol Loomis, Buffett seeks a New Buffett, Fortune (1 Mar 2007)

leverage. I comparison the two leading bond insurance companies, MBIA and Ambac Assurance, insured a combined USD 700 billion in municipal debt.6 Buffetts entrance into the bond insurance sector was typical Buffett. Shortly before he made his move, MBIA and Ambac Assurance had been caught in the sub-prime mortgage crisis, having significantly underwritten such structured products as sub-prime mortgage backed securities. With the weakening housing market leading to mortgage defaults, there was a dramatic revaluation of these complex structured securities. As a result, MBIAs and Ambacs shares were down for 2007, by 74% and 72%, respectively. The losses threatened the firms coveted AAA ratings, which rating agencies suggested might be difficult to sustain without new infusions of capital.7 Buffett had suggested that he would not underwrite structured products, in line with his well known mantra that one should be in investing only in things that you understand. Buffett had missed the tech run-up of the late 1990s by sticking to his mantra, and judging from Berkshires overally performance, it was clear that doing so had cost him little. Buffetts investing in bond insurance highlighted the importance of the sector and exemplified some of his investment acumen and philosophy, as expressed in the 2006 Annual Report to Berkshires shareholders: Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful. It was both an opportunistic and a well conceived move. His bet was that municipalities would see him as a sure thing, and though they might be forced to pay a premium price to insure their bonds with him instead of some other insurer, bond holders would ultimately be willing to accept them for a lower yield (cost) than if they had been insured by someone without Buffetts reputation. Furthermore, Buffett stood to benefit from the current troubles of the bond insurers, especially if their credit ratings were downgraded. Buffett was revered for consistently capitalizing on such situations. At the same time, the capital initially provided for BHAC was not especially large, given Berkshire Hathaways scale, which made some wonder why Buffett was unwilling to enter this new territory more forcefully. Did he think that the current players in the market were too big to fail? In other words, might there be some government intervention in the works that would help his competitors recover? Was he unsure of his own ability to run that particular business? Or was he simply being conservative, in line with his other mantra: avoid risk? Nevertheless, some believed that BHAC augured yet more success for Buffett. Donald Light, a senior analyst who tracked the insurance industry for Boston based Celent, a financial research and consulting firm, said simply, I learned a long time ago: Do not bet against Warren Buffett.8

6 Karen Richardson, The Buzz: Bond Insurers Brace for Buffett; Markets Major Players Already Under Pressure from Mortgage Fiasco, Wall Street Journal, 29 Dec 2003, B3 7 Yael Bizouati, Buffett Shakes Up Monolines: His Entry May Benefit the Industry but Not Existing Players, Investment Dealers Digest, 14 Jan 2008. In early 2008, Fitch Ratings placed the AAA ratings of MBIA, Ambac, and FGIC on rating watch negative. XL Capital was placed under review, and Fitch said it needed to raise $2b. The agency also warned that unless MBIA was able to obtain further capital commitments in addition to the $1b capital commitment the company had received from Warburg Pincus within 6 weeks, it would downgrade MBIAs rating by one notch, to AA+

After the fact, of course, many deals seemed obvious to many people. What was interesting about Buffett was that some of his deals made sense and were kind of obvious before the fact. What was it that he saw and others did not? What was it that made him act and others not? Was it capital or acumen or both? Or was it leadership? What baffled many Buffettologists9 about the Oracle of Omaha was his unwillingness to take any stake in the recently hit banking sector. With some banks and financial services companies losing as much as 40% of their market values since the summer of 2007 because of their involvement with complex securities linked to sub-prime mortgages, one might have thought that Buffett would be interested in Bear Stearns or Merril Lynch, but he had not been enticed by what he had seen (Exhibit 2); instead, several sovereign funds10 had stepped up: Tamasek of Singapore and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority had provided some much needed capital to Merril Lynch and Citigroup respectively, while the Chinese government had made a USD 5 billion investment in Morgan Stanley, all during the past three months. Critics observed that Buffett might have had bad memories of the Salomon Brothers deal back in 1991: He took control of Salomon Brothers (which later became part of Citigroup) in the midst of a scandal involving illegal bids in a Treasury auction and in an environment that was still recovering from the S&L crisis of the late 1980s. It took him 10 years to sell his investment in Salomon Brothers, which ended up being one of his worst performers.11 So far, we have not seen a deal that causes me to start salivating, Buffet told CNBC in December 2007. People know our phone number, and we havent seen anything we wanted to move on.12 Others noted that he already had key investments in that sector, including US Bancorp and Wells Fargo. Still, Buffetts disengagement from the financial sector begged the question whether the sovereign funds saw something that he did not. In recent years, Buffett had focused on emerging markets, in particular, China. In 2003, he bought a large stake in PetroChina, which made him its largest shareholder after Beijing. At the time, PetroChina was trading only in Hong Kong and New York. But in 2007, Buffett started selling shares in PetroChina, and by October 2007, he had sold all his positions in it. He believed that the bubble in China was too hot and that it was wise to exit when he did.13 A week after Buffett sold his stake, PetroChina had an IPO in 8 Bonded by Buffet, As Berkshire Hathaway Quietly Moves into the Business of Municipal Bond Insurance, Rivals and Bond Issuers Question the Outcome, BusinesWeek Online, 31 Dec 2007 9 This term was used broadly to refer to observers who watched Buffets every move in order to understand him 10 Government owned funds rumored to have as much as $2t in assets under management and often criticized for their lack of transparency and the political motivation behind their investment decisions 11 Francesco Guerrera and James Politi, Berkshire Caps a Week of Dazzling Dealing, Financial Times, 29 Dec 2007, 19. 12 Guerrera and Politi, Berkshire Caps a Week 13 Jason Kirby, PetroChinas Trillion Dollar Market Debut, Macleans, 19 Nov 2007, 140

Shanghai, and investors drove the stock to new highs, but it soon started falling: By mid-January 2008, it was down almost 40%. Buffett had been in the news for his largest investment ever: his decision to give the bulk of his vast fortune, at the time estimated at more than USD 40 billion, to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, whose main mission was to fight diseases worldwide, including malaria, AIDS, and tuberculosis. Buffett joined Bill and Melinda Gates as a trustee of the foundation. The giving would take place in stages over a number of years, as long as at least one of the two Gateses are active in it.14 Why did he decide to leave his fortune to the Gates Foundation? He had been friends of the Gateses for a long time, and was impressed with the way they pursued their mission. But one could imagine there was more to it than that: Real leaders produce real results, and in the Gateses, Buffett recognized true leadership abilities and a selfless passion for what they did. In many ways, this act of philanthropy was Buffetts most significant investment. An in typical Buffett fashion, eschewing diversification, he made it in only one foundation. Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway Warren Buffett was the second richest man on the planet, with an estimated net worth of USD 52 billion.15 His massive fortune was the result of his investments in Berkshire Hathaway, a holding company that is, a company that invested in other companies and often had controlling stakes in them and also invested independently in stocks across a variety of sectors. Berkshire Hathaway had holdings in insurance (General Re, Geico), apparel (Fruit of the Loom), and home furnishings (RC Willey), among others, as well ass non-controlling stakes in such iconic firms as Coca-Cola, American Express, AnheuseBusch, Wells Fargo, and US Bancorp. Buffett was also famous for his insistence on living quietly in Omaha, Nebraska, and for having studies under Professor Benjamin Graham, the guru of value investing, at Columbia University in the 1950s. Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway had had an amazing run. A recent academic study that analyzed the performance of Berkshire Hathaways equity portfolio found that Berkshire Hathaway was best characterized as a large cap growth fund that had beaten the market 28 out of 31 years, a performance that placed it in the 99.99the percentile. Specifically, between 1976 and 2006, Berkshires stock portfolio beat the S&P 500 index by 14.65% and a value weighted index of all stocks by 10.91%. Overall, the authors argued that Berkshire Hathaways results were consistent with investment skill rather than luck (see Exhibit 3 for a view of Berkshire Hathaways performance in 2002-08).16 Warren Buffetts Philosophy (Investment and Otherwise)

14 Carol J. Loomis, Warren Buffet Gives it Away, Fortune, 10 Jul 2006, 56 15 The Worlds Billionaires, Forbes.com, http://www.forbes.com/lists/2007/10/07billionaires_Warren-Buffett_COR3.html (accessed 13 Mar 2008) 16 Gerald S. Martin and John Puthenpurackal, Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery: Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway (working paper American University and University of Nevada Las Vegas, 2007)

Warren Buffett was famous for value investing: identifying and investing in undervalued firms that were likely to bounce back. As evidenced by his portfolio, he also liked to invest in large companies that had consistent earnings and low debt and that operated in either oligopolistic or near-monopolistic markets. Most importantly, he liked to invest in companies that had good management teams and high quality corporate governance and that were involved in a business he could understand. Buffett was well known not only for his investment wisdom but also for his overall wisdom about life. Numerous books and articles on this aspect of Buffett17 contained the following nuggets: On the importance of working with the right people: I choose to work with every single person that I work with. That ends up being the most important factor. I dont interact with people I dont like or admire. Thats the key. Its like marrying.18 On the usefulness of applying a skill acquired in one job on another: I am a better investor because I am a businessman and a better businessman because I am an investor19. I feel the same way about managing that I do about investing: its not necessary to do extraordinary things to get extraordinary results20. On his investment philosophy and sticking to his principles even as the world was constantly changing: Rule No. 1: Never lose money. Rule No. 2: Never forget Rule No. 121. If principles can become dated, theyre not principles22. Independent, critical thinking was of paramount importance for a leader and an investor. On whether he should rely on the recommendations of brokers: Never ask a barber if you need a haircut23.

17 See, for example, Janet Lowe, Warren Buffet Speaks: Wit and Wisdom from the Worlds Greatest Investor, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2007) 18 How to Live with a Billion, Fortune 11 Sep 1989, 20 19 Robert Lanner, Warren Buffetts Idea of Heaven: I Dont Have to Work with People I Dont Like, Forbes 18 Oct 1993 20 Letter from Warren Buffett to Mr. and Mrs. William H. Gates III, 26 Jun 2006, widely circulated over the Internet and reprinted in Janet Lowe, Warren Buffett Speaks. 21 Carol J. Loomis, The Inside Story of Warren Buffett, Fortune 11 Apr 2006, 26 22 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, 1988 23 Janet Lowe, Warren Buffet Speaks

Because investing was about the future, he cautioned that one needed to be able to understand change: Anything that cant go on forever will end24. He advocated personal evolution and the ability to change without abandoning ones principles, but admitted that change might not always go smoothly: I evolved. I did not go from ape to human or human to ape in a nice even manner.25 What Lay Ahead Warren Buffett had withstood the test of time. He was in a league of his own because no one else (including other legendary investors as Peter Lynch) had had such a consistent, and lengthy, record. Throughout the years, he had shown remarkable leadership in the world of investing, even as the world around him had changed many times and often in dramatic ways. It was perhaps his ability to anticipate change that had served him so well, together with his unique timing and discipline. In tough times, Buffett had not even hesitated to take action, as his involvement with Salomon Brothers would suggest, though even he was not always right. But his insights (based on unerring instincts) were so clear and, in some ways, so obvious that one might well wonder why there were not more like him. What was it that made Warren Buffett Warren Buffett? Critics had tried to poke holes in what Buffett did, or did not do, and had also focused on who the new Buffett would be and whether the new environment of hedge funds, private equity, and sovereign funds competing for cheap assets, and thereby pushing asset prices higher, had made him lose some of his edge. In his inimitable style, Buffett responded, I can spend money faster than Imelda Marcos when things are right, referring to the former Philippine First Lady and renowned shopper.26 But things had not been right in this new environment for quite a while. And Imelda Marcos never cared about price. Exhibit 1 Swiss Res Performance, 2002-08

24 The New Establishment 10, Vanity Fair Oct 1995, 280 25 L. J. Davis, Buffett Takes Stock, New York Times Magazine 1 Apr 1990, 16 26 Karen Richardson, After the Tumult, Is It Buffett Time? Wall Street Journal, 21 Aug 2007, C1

Exhibit 2 Performance of Merril Lynch and Bear Stearns, 2002-08

Exhibit 3 Berkshire Hathaways Performance, 2002-08

Вам также может понравиться

- Case Study - Stella JonesДокумент7 страницCase Study - Stella JonesLai Kok WeiОценок пока нет

- CNBC Transcript 2006 2019 02Документ1 575 страницCNBC Transcript 2006 2019 02N BОценок пока нет

- Washington PostBuffett Analysis1Документ2 страницыWashington PostBuffett Analysis1Calvin ChangОценок пока нет

- Mark Yusko's Presentation at iCIO: Year of The AlligatorДокумент123 страницыMark Yusko's Presentation at iCIO: Year of The AlligatorValueWalkОценок пока нет

- Ruane, Cunniff & Goldfarb Investor Day 2009 - TranscriptДокумент24 страницыRuane, Cunniff & Goldfarb Investor Day 2009 - TranscriptThe Manual of IdeasОценок пока нет

- Geico Case Study PDFДокумент22 страницыGeico Case Study PDFMichael Cano LombardoОценок пока нет

- Investing in Credit Hedge Funds: An In-Depth Guide to Building Your Portfolio and Profiting from the Credit MarketОт EverandInvesting in Credit Hedge Funds: An In-Depth Guide to Building Your Portfolio and Profiting from the Credit MarketОценок пока нет

- Blackbook Project On Foreign Exchange and Its Risk Management - 237312993Документ61 страницаBlackbook Project On Foreign Exchange and Its Risk Management - 237312993Aman Tiwari75% (4)

- Bruce Berkowitz On WFC 90sДокумент4 страницыBruce Berkowitz On WFC 90sVu Latticework PoetОценок пока нет

- 1976 Buffett Letter About Geico - FutureBlindДокумент4 страницы1976 Buffett Letter About Geico - FutureBlindPradeep RaghunathanОценок пока нет

- BerkshireHandout2012Final 0 PDFДокумент4 страницыBerkshireHandout2012Final 0 PDFHermes TristemegistusОценок пока нет

- Interviews Value Investing Guru Roger Montgomery About ValueableДокумент3 страницыInterviews Value Investing Guru Roger Montgomery About Valueableqwerqwer123100% (1)

- The 400 Richest Americans" List, and What Is The Source of His WealthДокумент16 страницThe 400 Richest Americans" List, and What Is The Source of His WealthCindy MingОценок пока нет

- RV Capital June 2015 LetterДокумент8 страницRV Capital June 2015 LetterCanadianValueОценок пока нет

- Distressed Debt InvestingДокумент5 страницDistressed Debt Investingjt322Оценок пока нет

- Michael L Riordan, The Founder and CEO of Gilead Sciences, and Warren E Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman: CorrespondenceДокумент5 страницMichael L Riordan, The Founder and CEO of Gilead Sciences, and Warren E Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman: CorrespondenceOpenSquareCommons100% (27)

- Berkshire Hathaway Audit Committee Report On Trading in Lubrizol Corporation Shares by David L. SokolДокумент18 страницBerkshire Hathaway Audit Committee Report On Trading in Lubrizol Corporation Shares by David L. SokolCNBCОценок пока нет

- SchlossДокумент188 страницSchlossEduardo FreitasОценок пока нет

- Three Hours With Warren - Complete Transcript - 2008-08-22Документ62 страницыThree Hours With Warren - Complete Transcript - 2008-08-22drunkdealmasterОценок пока нет

- Letter About Carl IcahnДокумент4 страницыLetter About Carl IcahnCNBC.com100% (1)

- Bridge With BuffetДокумент12 страницBridge With BuffetTraderCat SolarisОценок пока нет

- Profiles in Investing - Marty Whitman (Bottom Line 2004)Документ1 страницаProfiles in Investing - Marty Whitman (Bottom Line 2004)tatsrus1Оценок пока нет

- 1 L I LL I: WWW EscДокумент4 страницы1 L I LL I: WWW EscforexmastertanОценок пока нет

- Profit Guru Bill NygrenДокумент5 страницProfit Guru Bill NygrenekramcalОценок пока нет

- Value Investor Insight Play Your GameДокумент4 страницыValue Investor Insight Play Your Gamevouzvouz7127100% (1)

- Warren Buffett CNBC Transcript Feb-29-2016 PDFДокумент92 страницыWarren Buffett CNBC Transcript Feb-29-2016 PDFAndri ChandraОценок пока нет

- Schloss 2006Документ2 страницыSchloss 2006Logic Gate Capital100% (1)

- Value Investing Review of Warren Buffetts Investment Philosophy and PracticeДокумент13 страницValue Investing Review of Warren Buffetts Investment Philosophy and PracticeRoberto GonzasОценок пока нет

- In Search of The "Buffett Premium" - Free SampleДокумент22 страницыIn Search of The "Buffett Premium" - Free SampleRationalWalkОценок пока нет

- Mohnish Pabrai Chicago Meeting 2009 NotesДокумент3 страницыMohnish Pabrai Chicago Meeting 2009 NotesalexprywesОценок пока нет

- Bruce BerkowitzДокумент35 страницBruce BerkowitznewbietraderОценок пока нет

- Warren Buffett and GEICO Case StudyДокумент18 страницWarren Buffett and GEICO Case StudyReymond Jude PagcoОценок пока нет

- Buffett On ValuationДокумент7 страницBuffett On ValuationAyush AggarwalОценок пока нет

- BH 2015 AmДокумент14 страницBH 2015 Amva.apg.90100% (2)

- Graham and Doddsville - Issue 9 - Spring 2010Документ33 страницыGraham and Doddsville - Issue 9 - Spring 2010g4nz0Оценок пока нет

- Daily Journal Meeting Detailed Notes From Charlie MungerДокумент29 страницDaily Journal Meeting Detailed Notes From Charlie MungerGary Ribe100% (1)

- How David Sokol Lost His WayДокумент3 страницыHow David Sokol Lost His WayBisto MasiloОценок пока нет

- Buffett in Hindsight Foresight (2002)Документ8 страницBuffett in Hindsight Foresight (2002)MWGENERALОценок пока нет

- The Playing Field - Graham Duncan - MediumДокумент11 страницThe Playing Field - Graham Duncan - MediumPradeep RaghunathanОценок пока нет

- David Einhorn MSFT Speech-2006Документ5 страницDavid Einhorn MSFT Speech-2006mikesfbayОценок пока нет

- Vinall 2014 - ValuationДокумент19 страницVinall 2014 - ValuationOmar MalikОценок пока нет

- Summary New Venture ManagementДокумент57 страницSummary New Venture Managementbetter.bambooОценок пока нет

- Bibliophile Warren Buffett's Letter 1957-2017Документ165 страницBibliophile Warren Buffett's Letter 1957-2017Vishal Kedia0% (1)

- Schloss-10 11 06Документ3 страницыSchloss-10 11 06Logic Gate CapitalОценок пока нет

- Boyar ValueInvestingCongress 131609Документ71 страницаBoyar ValueInvestingCongress 131609vikramb1Оценок пока нет

- Warren Buffett - PetrochinaДокумент2 страницыWarren Buffett - PetrochinaJohn ReedОценок пока нет

- The Future of Common Stocks Benjamin Graham PDFДокумент8 страницThe Future of Common Stocks Benjamin Graham PDFPrashant AgarwalОценок пока нет

- To: From: Christopher M. Begg, CFA - CEO, Chief Investment Officer, and Co-Founder Date: July 16, 2012 ReДокумент13 страницTo: From: Christopher M. Begg, CFA - CEO, Chief Investment Officer, and Co-Founder Date: July 16, 2012 Recrees25Оценок пока нет

- Amitabh Singhvi L MOI Interview L JUNE-2011Документ6 страницAmitabh Singhvi L MOI Interview L JUNE-2011Wayne GonsalvesОценок пока нет

- Arithmetic of EquitiesДокумент5 страницArithmetic of Equitiesrwmortell3580Оценок пока нет

- Osmium Partners Presentation - Spark Networks IncДокумент86 страницOsmium Partners Presentation - Spark Networks IncCanadianValue100% (1)

- Steve Romick SpeechДокумент28 страницSteve Romick SpeechCanadianValueОценок пока нет

- PremWatsaFairfaxNewsletter7 12-20-11Документ6 страницPremWatsaFairfaxNewsletter7 12-20-11able1Оценок пока нет

- Financial Fine Print: Uncovering a Company's True ValueОт EverandFinancial Fine Print: Uncovering a Company's True ValueРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (3)

- To the Moon Investing: Visually Mapping Your Winning Stock Market PortfolioОт EverandTo the Moon Investing: Visually Mapping Your Winning Stock Market PortfolioОценок пока нет

- Competitive Advantage in Investing: Building Winning Professional PortfoliosОт EverandCompetitive Advantage in Investing: Building Winning Professional PortfoliosОценок пока нет

- Pilgrimage to Warren Buffett's Omaha: A Hedge Fund Manager's Dispatches from Inside the Berkshire Hathaway Annual MeetingОт EverandPilgrimage to Warren Buffett's Omaha: A Hedge Fund Manager's Dispatches from Inside the Berkshire Hathaway Annual MeetingРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- S.15 FINTECH Fintech and The City Sandbox 2 0 Policy and Regulatory Reform Proposals PDFДокумент34 страницыS.15 FINTECH Fintech and The City Sandbox 2 0 Policy and Regulatory Reform Proposals PDFNicolás J. Baquero M.Оценок пока нет

- HW#10 11.2 and 11.5 Implicit Diff and Application - MATH 104 - Fall 2023, Fall 2023 WebAssignДокумент1 страницаHW#10 11.2 and 11.5 Implicit Diff and Application - MATH 104 - Fall 2023, Fall 2023 WebAssignAbdullah AlaamОценок пока нет

- This Prospectus Is Important and Requires Your Immediate AttentionДокумент67 страницThis Prospectus Is Important and Requires Your Immediate Attentionmartin shineОценок пока нет

- Lecture 33 Credit+Analysis+-+Corporate+Credit+Analysis+ (Ratios)Документ33 страницыLecture 33 Credit+Analysis+-+Corporate+Credit+Analysis+ (Ratios)Taan100% (1)

- Investment AlternativesДокумент32 страницыInvestment AlternativesMadihaBhattiОценок пока нет

- Universiti Teknologi Mara Common Test 1: Confidential AC/AUG 2015/MAF253Документ6 страницUniversiti Teknologi Mara Common Test 1: Confidential AC/AUG 2015/MAF253Bonna Della TianamОценок пока нет

- Application of Fibonacci Numbers On Technical Analysis of Eur/Usd Currency PairДокумент10 страницApplication of Fibonacci Numbers On Technical Analysis of Eur/Usd Currency PairMohammad ArnoldОценок пока нет

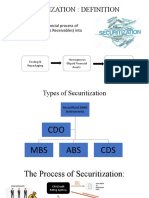

- SECURITIZATIONДокумент5 страницSECURITIZATIONASHISH KUMARОценок пока нет

- Pointers MKTG60Документ3 страницыPointers MKTG60Shan Sai BuladoОценок пока нет

- Rule of 69 - Meaning, Benefits, Limitations and MoreДокумент4 страницыRule of 69 - Meaning, Benefits, Limitations and MoreCandy DollОценок пока нет

- Farming AafsДокумент178 страницFarming AafsKezza Marie LuengoОценок пока нет

- AmatsДокумент3 страницыAmatsAldrin LiwanagОценок пока нет

- Aaafx Bonus T&C v1Документ3 страницыAaafx Bonus T&C v1alvin allesandroОценок пока нет

- E StatementДокумент10 страницE StatementMahendra LakkavaramОценок пока нет

- Clifford Chance Client Briefing IIFM MCM Agreement 16-Nov-2014Документ3 страницыClifford Chance Client Briefing IIFM MCM Agreement 16-Nov-2014karim meddebОценок пока нет

- MFM Chap-01Документ17 страницMFM Chap-01VEDANT XОценок пока нет

- Dabba TradingДокумент2 страницыDabba Tradingkushal90Оценок пока нет

- A Study On Portfolio ManagementДокумент3 страницыA Study On Portfolio ManagementEditor IJTSRDОценок пока нет

- Relevant Provisions of Companies ActДокумент19 страницRelevant Provisions of Companies Actrthi04Оценок пока нет

- Sol. Man. - Chapter 10 She 1Документ5 страницSol. Man. - Chapter 10 She 1Nikky Bless LeonarОценок пока нет

- NNFX Strategy Flow ChartДокумент2 страницыNNFX Strategy Flow ChartruwanzОценок пока нет

- Case Study AnswerДокумент3 страницыCase Study AnswerJAY MARK TANOОценок пока нет

- Quiz Black Scholes ModelДокумент3 страницыQuiz Black Scholes ModelMark AdrianОценок пока нет

- A2 Form MotherДокумент1 страницаA2 Form MotherStarОценок пока нет

- Impact of Latency On Forex TradingДокумент4 страницыImpact of Latency On Forex TradingalirahebiОценок пока нет

- Reliance Industries DCFДокумент35 страницReliance Industries DCFChirag SharmaОценок пока нет

- 506B Legal Aspects of Finance and Security LawsДокумент2 страницы506B Legal Aspects of Finance and Security LawsManthanОценок пока нет

- Basel II Capital Accord Report at SBPДокумент48 страницBasel II Capital Accord Report at SBPAamir Raza100% (1)

- Resume Joana de S Saad 1688571509Документ2 страницыResume Joana de S Saad 1688571509Hola HoolaОценок пока нет