Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Chaudhry 2007-Fictitiousuniversalism CS

Загружено:

ponkarooИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Chaudhry 2007-Fictitiousuniversalism CS

Загружено:

ponkarooАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

This article was downloaded by: [London School of Economics &] On: 06 July 2011, At: 10:58 Publisher:

Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Citizenship Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccst20

Fictitious universalism and substantive equality: A comment

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry

a a

Associate Professor of Political Science, 210 Barrows Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA, 94720, USA Available online: 16 Nov 2007

To cite this article: Kiren Aziz Chaudhry (1999): Fictitious universalism and substantive equality: A comment, Citizenship Studies, 3:3, 391-395 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13621029908420723

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Citizenship Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1999

Fictitious Universalism and Substantive Equality: A Comment

KIREN AZIZ CHAUDHRY This short comment highlights the political and conceptual substantinist feminist critiques of liberal citizenship.

Downloaded by [London School of Economics &] at 10:58 06 July 2011

The liberal notion of citizenship rests on the fiction of stripped down individuals who enjoy uniform and equal rights defined and enforced by a neutral state. Feminist challenges to this concept of citizenship can be roughly divided into two categories. The first highlights the ways in which the workings of the institutions of the state and the substance of the law in practice do not afford equal treatment to women. The second emphasizes the ways in which the very presumption of uniformity across gender, religious, cultural and national boundaries conceals and misrepresents substantive differences in the lived experiences of citizens Such that the practice of 'equal' law actually results in different degrees of representation and citizenship. Feminists arguing from these two positions disagree not only on the question of whether universal notions of citizenship are feasible and useful, but also on whether the legal realm can (or, for that matter, should) be separated from substantive experiences of power and identity. They differ on what it is, exactly, that should be included in the realm of 'citizenship'; and on whether or not the fiction of the disembodied individual is a useful tool in thinking about rights at all. Judging from the papers in this volume, with the possible exception of Suad Joseph's essay on Lebanon, the second mode of critique has triumphed. My aim here is examine the potential pitfalls of this approach. I want not simply to trace the outlines of political defeat in the substantivist position but also to suggest that citizenship need not necessarily encompass and embody the totality of our human experience. And perhaps, even, that such a condition might be even more oppressive than the fictitious individual in the liberal state. Of course, none of the societies discussed in this volume even aspire to that condition and this, in itself, is something that is not necessarily intellectually uninteresting or politically irrelevant. Grewal's argument that universalist discourses of human rights and citizenship reflect and institutionalize disequilibria in international power that undercut issues of socio-economic justice while enshrining bourgeois preoccupations with

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry, Associate Professor of Political Science, 210 Barrows Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. 1362-1025/99/030391-05 1999 Taylor & Francis Ltd 391

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry domestic violence and rape is perhaps the strongest statement of the substantivist position. An emphasis on the universal rights of women is politically suspect because '... gendering is done by multiple agents in a society and in widely divergent ways'. Thus, a generalized gender-based reading of a single notion of 'human rights' could potentially support the ideological agendas of majoritarian religious groups (such as the Hindu nationalists) and of the hegemonic process of economic globalization. With India in mind, Grewal argues that the substantive interests of women living in societies with group-based family law systems are therefore not best served through a uniform civil code but by intra-group efforts to reform religious laws to the benefit of women in ways that conform to the culturally divergent ways in which oppression is experienced. One can hardly argue with this prescription except to say that such internal reform has, historically, been exceedingly difficult for it asks the weakest members of a society to singlehandedly reshape the legal machine and the values that oppress them. I return to this point in my discussion of Suad Joseph's paper on Lebanon. Where Gurewal easily locates the pernicious impulse of universalizing agendas in international disequilibria of power, Hale, Ong and Moallem explore the interplay of struggles over political inclusion and exclusion as they occur within majority Muslim societies. The quest to achieve functional modernity while maintaining a distinctive Islamic identity has a long history in the Muslim world. Hale, Moallem and Ong are all concerned with how the construction of rights as attributes of groups or of individuals mediates secular and religious versions of nationalism, yet they have radically different views on the role of political Islam in changing articulations of citizenship. Ong's essay on the 'reasoning sisters' of Malaysia expresses most clearly the tensions between the oppositional and disciplinary aspects of contemporary Islamist discourses. Ong describes the paradoxical interplay between a religious elite seeking to control the social and sexual behavior of women and the deployment of Islamist discourses by Muslim feminists asserting the moral equality of women. The rationality claim of feminist Islamistsas 'reasoning sisters'is thus more deeply radical than a claim to legal equality because it subverts the foundational cultural belief that the control of women is necessary because of their irrational proclivities. Ong's analysis raises the fascinating question of whether citizenship rights need to be built on moral and substantive equality or on legal equality and certainly the one does not guarantee the other. At the same time, however, it is unclear how she weighs the relative success of oppositional Islam and Islam as a set of disciplinary practices. Feminist Islamism coexists with Islamic values (discipline, thrift) deployed by elites to withstand and overcome the challenges of global economic integration through a construction of cultural citizenship in a capitalist state. It is unclear how Ong reconciles the successful strategies of the Islamist feminists with the notion that cultural citizenship as a deeply conservative force; or how she perceives the opposition between clerics and technocratic elites in a regime where the state was deeply implicated in the legal, economic and political means of clerical ascent through its distribution of state-owned assets and other public resources. Whatever the balance between the conservative and liberatory potentials in Malaysian Islamism, Ong fails to ask, let alone 392

Downloaded by [London School of Economics &] at 10:58 06 July 2011

Fictitious Universalism and Substantive Equality answer, the question of why Islam and not some other ideational framework provides the language of legitimate debate on social issues at this particular juncture of history. If Ong's discussion places women in a public sphere where Islam negotiates cultural citizenship and Islamic capitalism in an increasingly interdependent global economy, Sondra Hale's analysis underscores the importance of Islamic citizenship as a potential source of national unity in a society torn by a seemingly interminable civil war. By distinguishing between the identities of 'Arab' and 'Muslim', the Sudanese regime not only constructs a cultural identity that is at once more inclusive (of various non-Arab tribes) and more exclusive (of the Christians), it also articulates an identity for the female citizen that liberates her from oppressive Arab customs, thus equating Islam with modernity. Free and equal in the new Islamic state, Sudanese women are also available for military mobilization and recruitment into the war against the secessionist south. Ong and Hale suggest that cultural nationalism in Sudan and Malaysia is not just a way of bypassing critical perspectives on capitalism and avoiding the identification of class-based divisions in society, for all successful nationalisms do just that. Rather, they point to the ways in which the quite obviously conservative impulses of Islamist cultural nationalism negotiate basic processes of nation-building and capitalism while simultaneously opening up spheres for radical critique and citizenship for women. While both present a subtle and nuanced appreciation of the tensions inherent in this accommodation, it needs to be stated that the seemingly benigneven liberatoryspheres that apparently open to women in Islamistdominated discourses only do so in the context of a prior abandonment of the goal of equal citizenship and, more importantly, do not necessarily constitute permanent avenues for negotiating citizenship. There is, in short, no guarantee that the besieged Sudanese regime will not revoke its 'progressive' version of female citizenship once conditions change, or that the technocratic elite in Malaysia will cease to need the 'reasoning sisters' in their (quite friendly) tussle with the Islamist clerics. The danger in abandoning struggles for legal equality based on the fiction of the decontextualized individual and the gender-neutral law-giving state is precisely that the bargain of cultural rights in post-colonial societies is notorious for its vulnerability to manipulation and obsolescence. A full recognition that legal equality in citizenship is imperfect and lacks substantive remedies for culturally entrenched differences between men and women does not, in other words, conflict with the desirable (but apparently abandoned) aim of achieving legal equality. What expresses itself as a tension in the essays by Ong and Hale takes the full form of advocacy in Moallem's discussion of gendered citizenship in Iran during the brutal secularist period of the Pahlavis and, again, after the consolidation of the Islamic regime in the early 1980s. Moallem begins with the commonplace observation that the creation of a uniform 'individual' in both these episodes of defining citizenship actually requires a subversion of the robust and variegated terrain of individual identity. In promoting modernism as Westemism the secularizing Shah created a 'hegemonic masculinity' that forced men to abandon religious identities while simultaneously creating a homogeneous category of (de-veiled) modern Iranian women. Secular citizenship in its initial rendition was 393

Downloaded by [London School of Economics &] at 10:58 06 July 2011

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry thus constructed on a cultural emasculation of both men and women. During the Revolution these hegemonic identities were disrupted only to be reintroduced through locational dichotomies constructed during the eight-year war with Iraq, and cemented into new homogenized Muslim citizens. Gender differences and more democracy, apparently, go hand in hand. Moallem's essay raises explicitly the question of whether we can (and should) look to the realm of citizenship to express the depth of our individuality in its evolving complexity and constructive specificity. If citizenship always requires the inherently violent subversion of most things that distinguish us from each other, does that mean that we cannot reasonably, profitably and collectively posit uniformity in the limited sphere of legal citizenship rights, reserving the full force of our uniqueness for a different realm? Moreover, is the homogeneity of the Westernized citizen that the Shah sought to impose on Iranian men and women through de-veiling really comparable to the much more explicitly gendered citizenship of post-Revolutionary Iran where women are literally missing from the public realm? In a world where culture is often upheld as the last bulwark of resistance against the homogenizing impulses of global capitalism and Western imperialism, these studies of the gender and citizenship illuminate the everyday negotiations and occasional victories of women living increasingly on the margins of a political debate in which their claims to equality have been all but jettisoned. We can recognize this condition only if we avoid the impulse to paint all modernity with the same brush of violent dehumanization. Indeed, the capacity to think politically rests precisely on being able to differentiate between different renditions of modernity and appreciate the glaring differences in the way the state constructs female citizenship. If each such construction of citizenship is brutal and oppressive, it does not necessarily suggest political equivalence. Moreover, it is crucial to recognize the deep political ambiguities in contemporary cultural nationalisms for the discursive strategies of anti-imperialism in the international arena might well be (and often are) deployed to subjugate, control and discipline any number of social and political groups domestically. I began my comments with the observation that feminism posed two broad categories of challenges to liberal notions of citizenship. In concluding with Suad Joseph's essay of patrilineality as a substructure of patriarchy in Lebanon, I hope to clearly illustrate of the pitfalls of taking the second mode of substantive critique to its logical conclusion. Joseph's essay is an illuminating review of the ways that patrilineality is both foundational to Lebanese religious subcultures and the ways that the state has used patrilineality to systematize ideas of citizenship. Apparently lamenting this systematization as a process of shrinking options for negotiating in different legal and social realms, Joseph shows how a legal system with numerous subdivisions based on religious distinctiveness generates mechanisms for reinforcing religious categories. Clerics in control of fashioning and enforcing family law encourage religious purity and condemn mixed marriages. Feminine experiences of citizenship, then, vary radically depending on the religious lineage of the woman in question. In substantive terms' the law conforms to the cultural and religious norms in which any particular woman lives, shaping each aspect of her rights and 394

Downloaded by [London School of Economics &] at 10:58 06 July 2011

Fictitious Universalism and Substantive Equality responsibilities as a citizen in ways different from women belonging to other religious groups. Joseph's aim is clearly to connect this plethora of citizenships to what she calls the 'substructure' of patriarchy, but her account raises the question of whether there actually is such a thing as 'citizenship' in Lebanon. The family laws that define various kinds of citizenship for Suni, Shi'a, Maronite and Druze women may well be substantively connected to their real lived experiences as members of a particular religious community, but this very fact means, also, that efforts to change the status of women in any of these legal traditions immediately comes up against the iron bedrock of patrilineality in much the same way that Muslim women trying to reshape their legal code in Grewal's India would face the foundational structures that oppress them. It is banal but perhaps necessary to mention that Lebanon is also a society where precisely the institutions and power structures that underpin and uphold this variegated notion of rights and entitlements that were responsible for a civil war that eclipsed any discussion about citizenship for decades, throwing groups into a conflict that was so protracted and bloody that 'Lebanon' achieved the dubious distinction of becoming a metaphor for civil violence. It is easy to couple the observation that liberal citizenship is based on the dual fiction of the homogenous individual and legal equality with unending examples of the substantive vacuity and even the violence of the real lived experiences of that very form of citizenship. Perhaps critical thinking about gender and citizenship in Islamic and Islamist countries can begin by asking why cultural nationalism and cultural citizenship have emerged as the dominant discursive strategy in so many societies today and by examining the novel barriers cultural citizenship poses for seeking legal equality. Only with that achievement in hand can we, cautiously, work to define and fight for substantive equality as women.

Downloaded by [London School of Economics &] at 10:58 06 July 2011

395

Вам также может понравиться

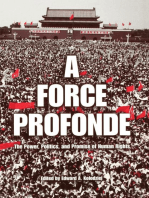

- A Force Profonde: The Power, Politics, and Promise of Human RightsОт EverandA Force Profonde: The Power, Politics, and Promise of Human RightsОценок пока нет

- On The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeДокумент8 страницOn The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeaneesОценок пока нет

- Attack On Human RightsДокумент16 страницAttack On Human RightsjazzeryОценок пока нет

- Islam and Democracy-FinalДокумент7 страницIslam and Democracy-FinalDan MarrОценок пока нет

- Feminism and Multiculturalism Mapping The TerrainДокумент27 страницFeminism and Multiculturalism Mapping The Terrainيوميات كيرا و مايا و كأي و اريانОценок пока нет

- Reply To Frow MorrisДокумент8 страницReply To Frow MorrisSimon BarberОценок пока нет

- 1-Solidarity Across Cultures PDFДокумент6 страниц1-Solidarity Across Cultures PDFachyanuddinОценок пока нет

- The EmergenceДокумент20 страницThe Emergenceusuariosdelserra1727Оценок пока нет

- Human Rights With Reference To WomenДокумент11 страницHuman Rights With Reference To WomenLydia NyamateОценок пока нет

- Civil Society in IranДокумент20 страницCivil Society in IranMoghset KamalОценок пока нет

- How Do We Accommodate Diversity in Plural SocietyДокумент23 страницыHow Do We Accommodate Diversity in Plural SocietyVictoria67% (3)

- Queerness 1ACДокумент8 страницQueerness 1ACKushal HaranОценок пока нет

- Islam and Politics 2 PDFДокумент41 страницаIslam and Politics 2 PDFNaiza Mae R. BinayaoОценок пока нет

- Body Politics: The Oxford Handbook of Gender and PoliticsДокумент3 страницыBody Politics: The Oxford Handbook of Gender and PoliticsRuxandra-Maria RadulescuОценок пока нет

- Safi Human RightsДокумент17 страницSafi Human Rightsserbaji mongiОценок пока нет

- Rhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarДокумент11 страницRhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarAlex WolfersОценок пока нет

- Dangaerous Discourses of Disability, Subjectivity and Sexuality.-68-74Документ7 страницDangaerous Discourses of Disability, Subjectivity and Sexuality.-68-74Jhonatthan Maldonado RamirezОценок пока нет

- Afropessimism K - Northwestern 2017Документ114 страницAfropessimism K - Northwestern 2017Evan JackОценок пока нет

- Ooi Kok Hin - Reading Review - Zakaria and Lipset - FinalДокумент3 страницыOoi Kok Hin - Reading Review - Zakaria and Lipset - FinalOoi Kok HinОценок пока нет

- Situations of SubtractionДокумент28 страницSituations of Subtractionsara33kingОценок пока нет

- Are Liberalism and Racial Equality IncompatibleДокумент4 страницыAre Liberalism and Racial Equality IncompatibleTALHA MEHMOODОценок пока нет

- M K Jha, Intro To Pol Theory, Lecture - 26, Citizenship 2Документ11 страницM K Jha, Intro To Pol Theory, Lecture - 26, Citizenship 2Dharmesh HarshaОценок пока нет

- Avtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismДокумент7 страницAvtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismJoana PupoОценок пока нет

- Response Paper-ExampleДокумент2 страницыResponse Paper-ExampleTasnim Tahmid TamakОценок пока нет

- Wounded AttachmentsДокумент22 страницыWounded AttachmentsMichael van der VeldtОценок пока нет

- A Look at The Intellectual, Cultural and Legal Bases of The Political and Social Project of Blacks in IraqДокумент21 страницаA Look at The Intellectual, Cultural and Legal Bases of The Political and Social Project of Blacks in IraqJalal ThiyabОценок пока нет

- Sirma Bilge - Intersectionality - Undone PDFДокумент20 страницSirma Bilge - Intersectionality - Undone PDFana carolinaОценок пока нет

- Social Construction of Nation A Theoretical ExplorationДокумент31 страницаSocial Construction of Nation A Theoretical ExplorationHansini PunjОценок пока нет

- Religion Revisited Lecture Kandiyoti June2009Документ7 страницReligion Revisited Lecture Kandiyoti June2009Lou JukićОценок пока нет

- CitizenshipДокумент6 страницCitizenshipDev Pratap singhОценок пока нет

- Age of Consent SarkarДокумент11 страницAge of Consent SarkarGade Jagadeesh ReddyОценок пока нет

- Managing Multicultural SocietiesДокумент11 страницManaging Multicultural SocietiesgarimaОценок пока нет

- "Cultural Citizenship" - Jan PakulskiДокумент31 страница"Cultural Citizenship" - Jan PakulskiPaper TigerlilyОценок пока нет

- Taylor Ma KaleДокумент13 страницTaylor Ma KaleSarphan UzunogluОценок пока нет

- Heba-Raouf Towards An Islamically Democratic SecularismДокумент12 страницHeba-Raouf Towards An Islamically Democratic SecularismAnas ElgaudОценок пока нет

- 01 - Liberalism and Multiculturalism (Barry)Документ12 страниц01 - Liberalism and Multiculturalism (Barry)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaОценок пока нет

- Rethinking The Interplay of Feminism and Secularism in A Neo-Secular AgeДокумент27 страницRethinking The Interplay of Feminism and Secularism in A Neo-Secular AgeNatalina Dass Tera LodatoОценок пока нет

- Intimate Investments: Homonormativity, Global Lockdown, and The Seductions of Empire by Anna M. AgathangelouДокумент25 страницIntimate Investments: Homonormativity, Global Lockdown, and The Seductions of Empire by Anna M. AgathangelouthemoohknessОценок пока нет

- Unit 4Документ7 страницUnit 4saurabh thakurОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Gender PoliticsДокумент4 страницыIntroduction To Gender PoliticsAlmiraОценок пока нет

- The Ambiguities Between Contention and Political Participation A Study of Civil Society Development in Authoritarian RegimesДокумент5 страницThe Ambiguities Between Contention and Political Participation A Study of Civil Society Development in Authoritarian RegimesVincentWijeysinghaОценок пока нет

- Somalia DissertationДокумент7 страницSomalia DissertationPayToWriteAPaperCanada100% (1)

- Islam and Democracy in The Middle East: The Impact of Religious Orientations On Attitudes Toward Democracy in Four Arab CountriesДокумент31 страницаIslam and Democracy in The Middle East: The Impact of Religious Orientations On Attitudes Toward Democracy in Four Arab Countriesaxilley5iliasОценок пока нет

- The Just and The Unjust - Serif MardinДокумент18 страницThe Just and The Unjust - Serif Mardinbilal.salaamОценок пока нет

- Aihwa ONG PDFДокумент27 страницAihwa ONG PDFElihernandezОценок пока нет

- SynthesisДокумент8 страницSynthesisCALIWA, MAICA JEAN R.Оценок пока нет

- Veiling and Women's Intelligibility John BornemanДокумент16 страницVeiling and Women's Intelligibility John BornemanR Hayim BakaОценок пока нет

- Canning-Rose-Gender, Citizenship and SubjectivityДокумент17 страницCanning-Rose-Gender, Citizenship and Subjectivitymesato1971Оценок пока нет

- Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology College of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Political ScienceДокумент5 страницMindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology College of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Political ScienceRochelle SabacОценок пока нет

- Sharia Beyond Theocracy and SecularismДокумент10 страницSharia Beyond Theocracy and SecularismT Anees AhmadОценок пока нет

- The Human Essence Was Secured by The Animalization of AnotherДокумент8 страницThe Human Essence Was Secured by The Animalization of AnotherIan Mackey-PiccoloОценок пока нет

- Henry Giroux EssaysДокумент14 страницHenry Giroux EssaysLejla NizamicОценок пока нет

- Islam and Democracy EssayДокумент8 страницIslam and Democracy EssayLaurie FischerОценок пока нет

- Scratching The Surface CommentaryiiiДокумент379 страницScratching The Surface Commentaryiii'Rafique Ahmed KhokharОценок пока нет

- Beyond Speaking Truth To PowerДокумент41 страницаBeyond Speaking Truth To PowerJúnia MarúsiaОценок пока нет

- Progressivism Anchored by Constitutionalism: For Dignity & HopeДокумент9 страницProgressivism Anchored by Constitutionalism: For Dignity & HopeTamirat WorkuОценок пока нет

- SEXUAL RormesДокумент19 страницSEXUAL Rormesapi-18504945Оценок пока нет

- Globalisation 01Документ9 страницGlobalisation 01mansioberoi_2009Оценок пока нет

- The Failed Experiment: Why Democracy is Struggling in Africa: World Series, #2От EverandThe Failed Experiment: Why Democracy is Struggling in Africa: World Series, #2Оценок пока нет

- McClintock Family FeudsДокумент21 страницаMcClintock Family FeudsJennifer VilchezОценок пока нет

- GRIZAL MIDTERM EXAM Short Term 2021 22 1Документ7 страницGRIZAL MIDTERM EXAM Short Term 2021 22 1Mariette Alex AgbanlogОценок пока нет

- The Place of The Cry of RebellionДокумент47 страницThe Place of The Cry of RebellionAlly AsiОценок пока нет

- Application, Reflection, and ExerciseДокумент4 страницыApplication, Reflection, and ExerciseAdiraОценок пока нет

- Lugo Border TheoryДокумент27 страницLugo Border Theorysudhansus81Оценок пока нет

- Nazi Party - Wilderness YearsДокумент4 страницыNazi Party - Wilderness YearsSabsОценок пока нет

- Appropriation As Nationalism in Modern African ArtДокумент18 страницAppropriation As Nationalism in Modern African ArtohbeullaОценок пока нет

- REFUGEE LAW SEYLA BENHABIB The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2021) - 215-227Документ13 страницREFUGEE LAW SEYLA BENHABIB The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2021) - 215-227Badhon DolaОценок пока нет

- Departement of Political Science Banaras Hindu University: Revised Syllabus, 2013-2014Документ19 страницDepartement of Political Science Banaras Hindu University: Revised Syllabus, 2013-2014Vipul AggarwalОценок пока нет

- The Rise of Filipino NationalismДокумент3 страницыThe Rise of Filipino NationalismIsabel FlonascaОценок пока нет

- Cosmopolitan Democracy: Re-Evaluation of Globalization and World Economic SystemДокумент57 страницCosmopolitan Democracy: Re-Evaluation of Globalization and World Economic SystemAlex MárquezОценок пока нет

- Afrikanner NationalismДокумент16 страницAfrikanner NationalismFaelan LundebergОценок пока нет

- Yeats, Ireland and Fascism by Elizabeth CullingfordДокумент259 страницYeats, Ireland and Fascism by Elizabeth CullingfordDonnchadОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 175.176.46.131 On Sun, 17 Oct 2021 10:10:25 UTCДокумент15 страницThis Content Downloaded From 175.176.46.131 On Sun, 17 Oct 2021 10:10:25 UTCGen UriОценок пока нет

- Nationalism and Its ExplanationДокумент33 страницыNationalism and Its ExplanationFayyaz AliОценок пока нет

- Cps First Sem SyllabusДокумент15 страницCps First Sem SyllabusDanexОценок пока нет

- Unit 29 Gender/Women Under Colonialism: StructureДокумент9 страницUnit 29 Gender/Women Under Colonialism: StructureKshitij Ramesh DeshpandeОценок пока нет

- Lesson 3 A History of Global PoliticsДокумент6 страницLesson 3 A History of Global PoliticsAnnie Ruth CamiloОценок пока нет

- Unit Plans ss201Документ24 страницыUnit Plans ss201api-300964436Оценок пока нет

- Types of Terrorism: Gus MartinДокумент19 страницTypes of Terrorism: Gus MartinViolina RobuОценок пока нет

- Naciones DivididasДокумент30 страницNaciones Divididasdaniel0alonso0gonz0lОценок пока нет

- John Collins-Occupied by Memory - The Intifada Generation and The Palestinian State of Emergency-NYU Press (2004)Документ302 страницыJohn Collins-Occupied by Memory - The Intifada Generation and The Palestinian State of Emergency-NYU Press (2004)Ahmad SabbirОценок пока нет

- 03 Rizal in The Context of 19th Century Philippines - SchumacherДокумент10 страниц03 Rizal in The Context of 19th Century Philippines - SchumacherJan Kevin AntonioОценок пока нет

- Activity 2: Short Answer Essay On NATIONALISMДокумент2 страницыActivity 2: Short Answer Essay On NATIONALISMHell YeahОценок пока нет

- Political Sociology PresentationДокумент4 страницыPolitical Sociology PresentationAtalia A. McDonaldОценок пока нет

- PreviewpdfДокумент50 страницPreviewpdfDaniel QuiñonesОценок пока нет

- Text and Transformation - Refiguring Identity in Postcolonial PhilДокумент288 страницText and Transformation - Refiguring Identity in Postcolonial PhilkeiОценок пока нет

- Art Appreciation EssayДокумент8 страницArt Appreciation EssayDanielОценок пока нет

- Romantic Nationalism As Historical DramaДокумент1 страницаRomantic Nationalism As Historical DramaToufik AhmedОценок пока нет

- Croatian Ustashas and Policy Toward Minorities PDFДокумент449 страницCroatian Ustashas and Policy Toward Minorities PDFMarko Cvarak75% (4)