Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

A Review of The End of Poverty by JDS - Clive Hamilton

Загружено:

manawatitiИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Review of The End of Poverty by JDS - Clive Hamilton

Загружено:

manawatitiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A review of The End of Poverty by Jeffrey Sachs (Penguin)

Clive Hamilton The Age, 2 July 2005 This book could be subtitled, My Amazing Adventures as an International Economic Guru. Having saved Bolivia from the perils of hyperinflation (when he was just 30) and rescued Poland and Russia from the deadweight of communism, our superhero has now set himself the biggest challenge of all delivering the world from the curse of poverty. Jeffrey Sachs is a Harvard-trained economist who has become something of an academic superstar with his unusual mix of neoliberal economics and willingness to attack the IMF for its dogmatism and the Bush Administration for its lack of concern for the poor and bullying approach to world affairs. As a result he has been embraced by many who dislike Bush and the IMF but have no understanding of economics and power politics. The foreword to the book was written by rock celebrity turned poverty campaigner Bono, and never were a more oleaginous and self-obsessed thousand words penned. According to Bono, the marriage of placards and markets was a natural one and he tells the story of how he and Jeffrey bonded over their mutual determination to abolish poverty in Africa while flying first-class over that benighted continent. Of Sachs he writes: In time, his autograph will be worth a lot more than mine. Gosh, surely he will never be that famous! The warm reception given to this book by people who should know better is a testament to the decline of political understanding among progressives after two decades of neoliberal victories. A bleeding heart is a good complement to, but no substitute for, a hard-headed analysis of social structure and the deployment of power. In Jeffrey Sachs Harvard meets MTV. One cant help thinking that Western colonialism has morphed into a new way of disempowering the Third World: if only we in the West can find it in our hearts then we can abolish poverty. I know, lets have a rock concert and all the young people will realise that the answer lies in their hands. But stripped of the narcissism, what is Sachs answer to global poverty? How can he support his claim that extreme poverty can be eliminated by 2025? Sachs has developed a new sub-discipline called clinical economics. Each failed economy is unique and its ailments must be carefully diagnosed before a prescription suited to the condition can be written. Sachs includes helpful checklists to diagnose the causes of economic decline and formulate a cure for the malady. He says that his new economics was developed by observing his wife Sonias clinical practice of paediatrics. An economy is like a human body, he argues, and only an economic doctor willing to understand its complex workings can cure it. Of course, economies are not in any sense like bodies, not even in their complexity; if we want a

medical analogy, a better one might be a dysfunctional hospital run by a drug company with a commercial interest in perpetuating illness. Sachs clinical economics is little more than standard neoclassical economics. Just like the IMF colleagues he likes to attack (many of whom he says he trained), Sachs believes above all that the answer lies in markets. For all of the encomiums written by well-meaning but nave enthusiasts praising Sachs for tempering his economic theory with real world experience, Sachs cannot escape his training. In US graduate schools in economics, the free market is king. Its not just an analytical framework, its a worldview that gets into the bones of every graduate. At one point Sachs recounts how in the 19th century the East Indies and the West Indies did not benefit from the opening of trade with the West and quotes Adam Smith to the effect that the maldistribution of the gains from trade was due not to trade itself but to the military advantage that Europe had over the natives. Thats the problem with trade, foreign investment and privatisation; the theorems of the textbooks are always turned into reality by actual people with their own interests. One could make the same analysis about the maldistribution of the benefits of the recent US-Australia Free Trade Agreement and indeed the world trading system managed by the WTO. Somehow the poor countries always seem to get screwed, whether it be through multinational drug companies destroying local firms making cheap drugs, Third World food producers unable to get access to lucrative Western markets or corrupt elites skimming profits at every turn. In The End of Poverty Sachs details how he has applied his clinical economics around the world. He is happy to claim the successes the recipe for Polands transition to a market economy was tapped out by Sachs late one night in a Warsaw newspaper office. For good measure he claims to have raised a billion dollar currency stabilisation fund in a week. But he denies responsibility when things go badly wrong, as they did in Russia. When Russia accepted Sachs shock therapy the results were disastrous. The economy collapsed in the early 1990s resulting in mass poverty, destitution and a sharp and unprecedented increase in the death rate. Although he claims the privatisation process happened after he had cut his links with Russia, many of the nations principal productive assets fell into the hands of crooks, triggering an economic and social catastrophe that Russia is still trying to cope with. Undoubtedly Sonia has medical indemnity insurance to cover her for any mistakes; her husband, per contra, seems infallible. Sachs praises the anti-globalisation movement for being well-meaning but chastises it for attacking global corporations. Its not their fault, he insists; its our fault for not providing the right guidelines. The apogee of this dangerous naivety comes in his claim that oil companies like ExxonMobil should not be blamed for global warming. Climate change occurs because government isnt doing its job. It is as if Sachs has systematically wiped from his consciousness the vast accumulation of evidence that ExxonMobil in effect determines US government policy on climate change. But in the textbooks we find

one box for firms and another for government and the only flow of money is from government to firms to buy staplers. Like all of us he wants capitalism to have a more human face, except that the institutions best suited to compelling capitalism to be more humane have been under sustained and effective attack by the advocates of the free market, including Sachs, for two decades. In the sixties and seventies a flourishing debate about poverty and development saw the emergence a school of economists and other experts who understood intimately the impact of poverty in the Third World and what it would take to solve the problem. They supported capitalism but were not one-eyed fans of the market. But reading Sachs you would think that he alone discovered the problem of underdevelopment. The great thinkers of development studies Paul Streeton, Michael Lipton, Fernando Cardoso receive no mention at all from Sachs. Even the venerable Amartya Sen, who was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on poverty and development, attracts only one dismissive reference. Sachs ignorance of intellectual history is matched by his lack of generosity. Like his fellow economists who control the institutions of global economic management, Sachs is a cheerleader for Enlightenment rationality. Yet time and again he must give awkward acknowledgment to the fact that the power of a few is enough to cancel out any amount of rationality. But for Sachs power is never a structural feature of the world. Its something that somehow ends up in the hands of rogue Third World dictators or corrupt CEOs; the bad apple theory of power. How the Russian oil barons must smile into their wine glasses and give thanks to Jeffrey Sachs political naivety. As each chapter recounting his exploits passes, the reader begins to wonder whether Sachs imagines himself to be not so much a skilled healer as a messiah. Not even the most brilliant doctor pretends that only he or she can solve all ills, yet the underlying message of The End of Poverty is that the author alone has the solution to the worlds problems. No wonder he has found comfort in the company of superannuated pop stars more familiar than anyone with raging egos and shameless self-promotion.

Clive Hamilton is Executive Director of The Australia Institute and co-author of Affluenza (Allen & Unwin 2005).

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sickness is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us from Pandemics or ItselfОт EverandThe Sickness is the System: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us from Pandemics or ItselfРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- Thesis Gloria AlvarezДокумент73 страницыThesis Gloria AlvarezRoger Vila100% (2)

- Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree WorldОт EverandSocialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree WorldРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (25)

- Solution:: Purchases, Cash Basis P 2,850,000Документ2 страницыSolution:: Purchases, Cash Basis P 2,850,000Jen Deloy50% (2)

- The Culture of Narcissism American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations by Christopher LaschДокумент304 страницыThe Culture of Narcissism American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations by Christopher Laschlansel347807193% (15)

- The Failure of Laissez Faire Capitalism and Economic Dissolution of the WestОт EverandThe Failure of Laissez Faire Capitalism and Economic Dissolution of the WestРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4)

- Application Form EMPLOYEES CAR LOAN SCHEME (New/Reconditioned Car)Документ4 страницыApplication Form EMPLOYEES CAR LOAN SCHEME (New/Reconditioned Car)assadОценок пока нет

- Jefrrey SachsДокумент9 страницJefrrey SachsEugeneLangОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx's Revenge - Class Struggle Grows Around The World - TIMEДокумент4 страницыKarl Marx's Revenge - Class Struggle Grows Around The World - TIMENishan ChatterjeeОценок пока нет

- The Age of MerchantsДокумент246 страницThe Age of Merchantssergio dezorziОценок пока нет

- 50 Books Reviews For CSS 2024Документ23 страницы50 Books Reviews For CSS 20242k20ghulammurtazaОценок пока нет

- Whither MarxismДокумент3 страницыWhither MarxismSubba RajuОценок пока нет

- The Impudence of ImpotenceДокумент2 страницыThe Impudence of ImpotenceAnthony St. JohnОценок пока нет

- Whyte White CollarДокумент263 страницыWhyte White CollarNatalia Savelyeva100% (2)

- Revolution or DisengagementДокумент5 страницRevolution or DisengagementRobert BonomoОценок пока нет

- Remember Marx For How Much He Got WrongДокумент5 страницRemember Marx For How Much He Got WrongMircea PanteaОценок пока нет

- The Suicide of A SuperpowerДокумент8 страницThe Suicide of A SuperpowerRotl RotlRotlОценок пока нет

- June 09Документ95 страницJune 09Marcelo AraújoОценок пока нет

- JohnGray HeresiesДокумент10 страницJohnGray HeresiesedeologyОценок пока нет

- The ThunderboltДокумент111 страницThe ThunderboltSauvikChakravertiОценок пока нет

- We Are All Very AnxiousДокумент8 страницWe Are All Very AnxiousOinkz OinkzzОценок пока нет

- Capitalism, Socialism and Nationalism: Lessons From History by Niall FergusonДокумент18 страницCapitalism, Socialism and Nationalism: Lessons From History by Niall FergusonHoover Institution100% (6)

- Against Leviathan: Government Power and a Free SocietyОт EverandAgainst Leviathan: Government Power and a Free SocietyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- Marxists and MoralityДокумент7 страницMarxists and MoralityJavier ValdezОценок пока нет

- A View From Trough - Richard Levins - Monthly ReviewДокумент9 страницA View From Trough - Richard Levins - Monthly ReviewPradeep KumarОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Socio-Economic Integration: The Civil Economy Perspective For A Participatory SocietyДокумент14 страницEnhancing Socio-Economic Integration: The Civil Economy Perspective For A Participatory SocietyChristofer AndrewОценок пока нет

- Why The Left Must Destroy Free Speech - or Be Destroyed - LewRockwellДокумент3 страницыWhy The Left Must Destroy Free Speech - or Be Destroyed - LewRockwelltokalulu8859Оценок пока нет

- Terrell HertzДокумент4 страницыTerrell HertzAndrew S. TerrellОценок пока нет

- Their Criticism Is A Form of Asymmetrical Warfare That Seeks To Undermine and Collapse The United States. Nyquist 09Документ2 страницыTheir Criticism Is A Form of Asymmetrical Warfare That Seeks To Undermine and Collapse The United States. Nyquist 09Master_HeideggerОценок пока нет

- Medicina Al Final Del ImperioДокумент3 страницыMedicina Al Final Del ImperioTano TanitoОценок пока нет

- Semiotexte Anti Oedipus - From Psychoanalysis To SchizopoliticsДокумент99 страницSemiotexte Anti Oedipus - From Psychoanalysis To SchizopoliticsOriol López Esteve100% (1)

- Foundations of A Free Society Nathaniel BrandenДокумент9 страницFoundations of A Free Society Nathaniel BrandenJoshua GonsherОценок пока нет

- The Rich in Public Opinion: What We Think When We Think About WealthОт EverandThe Rich in Public Opinion: What We Think When We Think About WealthОценок пока нет

- Max Horkheimer - The Jews and Europe (1939)Документ18 страницMax Horkheimer - The Jews and Europe (1939)Dimitri RaskolnikovОценок пока нет

- Colonized by CorporationsДокумент4 страницыColonized by Corporationslmm58Оценок пока нет

- Liberalism and Socialism Mortal Enemies or Embittered Kin 1St Edition Matthew Mcmanus Full ChapterДокумент54 страницыLiberalism and Socialism Mortal Enemies or Embittered Kin 1St Edition Matthew Mcmanus Full Chapterbertha.kamen816100% (5)

- The Pinay Circle: The Nazis Were A Bunch of Extremists That Didn T Represent Conservatives or LiberalsДокумент25 страницThe Pinay Circle: The Nazis Were A Bunch of Extremists That Didn T Represent Conservatives or LiberalsTimothyОценок пока нет

- In and Out of Crisis: The Global Financial Meltdown and Left AlternativesДокумент144 страницыIn and Out of Crisis: The Global Financial Meltdown and Left AlternativesDemokratizeОценок пока нет

- It Didn't Have to Be This Way: Why Boom and Bust Is Unnecessary—and How the Austrian School of Economics Breaks the CycleОт EverandIt Didn't Have to Be This Way: Why Boom and Bust Is Unnecessary—and How the Austrian School of Economics Breaks the CycleРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (4)

- Andrew S. Terrell - Capitalism & Globalization! Fall 2009Документ5 страницAndrew S. Terrell - Capitalism & Globalization! Fall 2009Andrew S. TerrellОценок пока нет

- Man 3.7-8 July-Aug 1935Документ8 страницMan 3.7-8 July-Aug 1935JesseCohnОценок пока нет

- Sunday, 09 May 2010: Cyrus BinaДокумент22 страницыSunday, 09 May 2010: Cyrus Binand525ulhcfoОценок пока нет

- Thomas - What Was The New DealДокумент6 страницThomas - What Was The New DealSamson FungОценок пока нет

- A Short History of Neo-Liberalism. Twenty Years of Elite EconomicsДокумент8 страницA Short History of Neo-Liberalism. Twenty Years of Elite EconomicsNATALIA CANDADO LOPEZОценок пока нет

- 6 BaruchelloLintner Final DraftДокумент21 страница6 BaruchelloLintner Final DraftTo-boter One-boterОценок пока нет

- Bus 5111 Discussion Assignment Unit 7Документ3 страницыBus 5111 Discussion Assignment Unit 7Sheu Abdulkadir BasharuОценок пока нет

- ERP Fit Gap AnalysisДокумент20 страницERP Fit Gap Analysiskarimmebs100% (1)

- BSBTEC601 - Review Organisational Digital Strategy: Task SummaryДокумент8 страницBSBTEC601 - Review Organisational Digital Strategy: Task SummaryHabibi AliОценок пока нет

- Working at WZR Property SDN BHD Company Profile and Information - JobStreet - Com MalaysiaДокумент6 страницWorking at WZR Property SDN BHD Company Profile and Information - JobStreet - Com MalaysiaSyakil YunusОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9Документ2 страницыChapter 9mmaОценок пока нет

- Bank Statement PDFДокумент5 страницBank Statement PDFIrfanLoneОценок пока нет

- Financial Planning and Control: Prof. Dr. Bengü VURANДокумент20 страницFinancial Planning and Control: Prof. Dr. Bengü VURANAhmet ÖzelОценок пока нет

- CIMB Strategy BriefДокумент328 страницCIMB Strategy BriefLesterОценок пока нет

- International Economics - Sample Exam Questions 2 Multiple Choice Questions (2 Points For Correct Answer, 0 For Blank Answer, - 1 For Wrong Answer)Документ3 страницыInternational Economics - Sample Exam Questions 2 Multiple Choice Questions (2 Points For Correct Answer, 0 For Blank Answer, - 1 For Wrong Answer)مؤمن عثمان علي محمدОценок пока нет

- 2 Sample Narrative Cover LettersДокумент2 страницы2 Sample Narrative Cover LettersJoban SidhuОценок пока нет

- Using Financial Statement Information: Electronic Presentations For Chapter 3Документ47 страницUsing Financial Statement Information: Electronic Presentations For Chapter 3Rafael GarciaОценок пока нет

- Sources of Capital: Owners' Equity: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinДокумент29 страницSources of Capital: Owners' Equity: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinNileshAgarwalОценок пока нет

- Solution Manual For Cornerstones of Cost Management 4th Edition Don R Hansen Maryanne M MowenДокумент46 страницSolution Manual For Cornerstones of Cost Management 4th Edition Don R Hansen Maryanne M MowenOliviaHarrisonobijq100% (78)

- The Circular Business Model: Magazine ArticleДокумент11 страницThe Circular Business Model: Magazine ArticleArushi Jain (Ms)Оценок пока нет

- DISCOUNT (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com)Документ15 страницDISCOUNT (WWW - Freeupscmaterials.wordpress - Com)k.palrajОценок пока нет

- Mpac522 GRP AssignmntДокумент4 страницыMpac522 GRP AssignmntShadreck VanganaОценок пока нет

- QuizДокумент4 страницыQuizPraveer BoseОценок пока нет

- Explain Multiproduct Breakeven Analysis. What Is The Assumption On..Документ3 страницыExplain Multiproduct Breakeven Analysis. What Is The Assumption On..Anutaj NagpalОценок пока нет

- 2019 Edp Unit 2 PDFДокумент19 страниц2019 Edp Unit 2 PDFchiragОценок пока нет

- Unit 3macroДокумент16 страницUnit 3macroAMAN KUMARОценок пока нет

- 17 (Adil Mehraj)Документ8 страниц17 (Adil Mehraj)Sakshi AgarwalОценок пока нет

- E0079 Rewards and Recognition - DR ReddyДокумент88 страницE0079 Rewards and Recognition - DR ReddywebstdsnrОценок пока нет

- 高盛IPO全套教程Документ53 страницы高盛IPO全套教程MaxilОценок пока нет

- Banking 18-4-2022Документ17 страницBanking 18-4-2022KAMLESH DEWANGANОценок пока нет

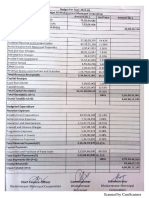

- Budget 2019-20Документ21 страницаBudget 2019-20Pranati ReleОценок пока нет

- Adm Excel EtДокумент168 страницAdm Excel EtShashank PullelaОценок пока нет

- Meaning and Definition of Audit ReportДокумент50 страницMeaning and Definition of Audit ReportomkintanviОценок пока нет

- Royal British College, Inc.: Business FinanceДокумент4 страницыRoyal British College, Inc.: Business FinanceLester MojadoОценок пока нет