Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Comment Narrative

Загружено:

Publius1776Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Comment Narrative

Загружено:

Publius1776Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Brett Seifried Narrative The Gauntlet Thrown [Opening line]

ALR Comment Narrative

The rocky course of the this regulation is rooted in the legislation which defined its environment. The BRCA, like any legislation, is the fortuitous byproduct of wrestling lobbying interests, wrangling legislative votes, and wresting compromise out of contention. To reach this compromise, of course, gaps are left unfilled1 , later to be bolstered by the expertise of an entrusted federal agency. The current literature has no shortage of models for explaining the rulemaking process: from interest group pluralism2 to civic republicanism3; from public choice

For an interesting discussion of how leaving gaps actually increases social well-being, see

William T. Mayton, The Possibilities of Collective Choice: Arrows Theorem, Article I, and the Delegation of Legislative Power to the Administrative Agencies, 1986 Duke L.J. 948, 952 (arguing that the bureaucratic nature of agencies allows for a dictatorship in technical matters and may increase social well-being).

2

E.g., Richard B. Stewart, The Reformation of American Administrative Law, 88 Harv. L. Rev.

1669 (1975).

3

E.g., Mark Seidenfeld, A Civic Republican Justification for the Bureaucratic State, 105 Harv.

L. Rev. 1551 (1992).

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

economics 4 to rationalizing substantive welfarism5 ; from positivism6 to structural political theory 7. Each is useful and each is limited. The common thread, though, of the various models of agency rule-making is a presumption of some rationality. Each model presumes, at least, that the final rules issued by the agency are the result, somehow, of a reasoned, rational, and considered development which incorporates the insights of notice-and-comment into a final, settled and universal rule. In short, the rule-making process creates rules as a result of rational decisions and insights, with the literature split as to the precise manner and motivation for a particular rule. Yet, the traditional narrative lacks, or oversteps, a logically preceding and necessary step: the Darwinian principle. This insight, the Darwinian insight, has been applied often to the

E.g., David B. Spence and Frank Cross, A Public Choice Case for the Administrative State, 89

Geo. L.J. 97 (2000).

5

E.g., Cass R. Sunstein, One Case at a Time: Judicial Minimalism on the Supreme Court, 31

(1999) (asserting that most administrative law is an effort to ensure that reasons are given for all agency action).

6

E.g.,Pablo T. Spiller, A Positive Political Theory of Regulatory Instruments: Contracts,

Administrative Law or Regulatory Specificity?, 69 S. Cal. L. Rev. 477 (1996).

7

E.g., Matthew D. McCubbins et al., Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative

Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies, 75 Va. L. Rev. 431 (1989).

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

common law 8, and broadly to the rulemaking aspects of the federal agencies. A recent rash of administrative scholarship picked up this gauntlet, and applied complexity theory to administrative law, and path dependency theory, and impossibility theory, and arrow theory, among others. Through all this new scholarship, at least one lesson becomes clear: the systemic basis of the agency has a vast, arational impact on the rules it conceives to propose. Rules evolve, or rather the ideas underlying the rules evolve9 , before a proposed rule is even

See generally Simon Deakin, Evolution for our Time: Toward a Theory of Legal Memetics, in

51 Current Legal Problems, 1, (M.D.A. Freeman ed., 2002) (tracing the history of Darwinian analysis in social science and law in particular, and the resurgence of legal darwinianism in the wake of the law and economics movements of the 1970s); compare, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Law in Science and Science in Law, 12 Harv. L. Rev. 433, 445446 (1899) (ruminating, rather unscientifically, on the scientific study of the morphology and transformation of human ideas in the law and pondering the flowering of complex legal doctrine from its rudimentary beginnings to the complex and artificial conceptions of civilized life), with Mark J. Roe, Chaos and Evolution in Law and Economics, 109 Harv. L. Rev. 641, 643 (1996) (delinking common law legal evolution from Law and Economics teleology of efficiency by explaining the possibility of local equilibriums hindering efficient development in comparative corporate law).

9

See Michael Fried, Evolution of Legal Concepts: The Memetic Perspective, 39 Jurimetrics J.

291, 30708 (1999) (explaining how legal ideas are the evolving genotype, and develop as ideas, and are expressed phenotypically as expressed legal rules in print within legal reporters, thereby demonstrating that the rule is only the expression of the evolving idea).

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

considered, and long before it is decided or codified. Further, the systemic environment may also selects toward rule proposals which can best survive scrutiny and application10. The theoretical narrative now recognizes that a natural, arational, systemic, and determinable selective pressure sets the potential courses of growth before any conscious decision is made. The rulemaking environment sets the stage for the potential rules eventual content.11 This comment will apply these recent insights to a case studythe FECs soft money

10

This principle is the foundation of the Law and Economics analytical model. In its most basic

form, the model proposes that less efficient rules will be challenged more in litigation, and therefore will be adapted or overruled. As this process works, new rules will develop which are challenged less, and thus the law moves toward a uniform, stable, and efficient legal rule regardless of the particularly of the challenge or its place or time. See Robert Cooter, et al., Liability Rules, Limited Information, and the Role of Precedent, 10 Bell Journal of Economics, 36673 (1979) (explaining the dynamic of challenges to inefficient rules leading to less challenged more efficient rules); see also George L. Priest, The Common Law Process and the Selection of Efficient Rules, 6 J. Legal Stud. 65, 65 (1977) (theorizing that, because of the systemic efficiency seeking dynamic, judges are unable to influence the content of the law to fully reflect their attitudes toward efficiency.).

11

Cf., Anthony Niblett, Richard A. Posner, and Andrei Shleifer, The Evolution of a Legal Rule,

39 J. Legal Stud. 325, 354, 355 (2010) (determining, through statistical analyses of all caselaw surrounding the Economic Loss Rule in construction contract disputes, that there was no national convergence toward a standard rule but rather localized convergences based on geographic area of suit, experience of the court dealing with the claim, relative economic power of the parties, and the status of the rules idiosyncratic variations within that jurisdiction).

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

solicitation regulations, their rejection in the Shays series of cases, and the FECs reformulation after the casesto examine if and how the Darwinian model is particularly enlightening where a regulation is subject to repeated dispute and has reached seeming equilibrium. This comment proposes that the development of federal regulations controlling the raising of soft money by federal candidates illuminates how, after recognizing the necessary condition of Darwinian selective pressure, to identify a rule at a local equilibrium point. Section I sets out the regulation and lays out a thumbnail sketch of its origins, development, varieties, and current status. This section is not a comprehensive legislative nor administrative history, but instead provides the substantive background to discuss the selective pressures that have shaped the rule. Section II lays out the Darwinian principle, its origins in biology, the subsequent use of the insight in social science and the law, and particularly the notions of local equilibria and complex system dynamics. Section III lays out the various challenges the theory must, and does, meet and then explains why the principle is a necessary condition of understanding a rule at a local peak in its development. Section IV finally applies the principles and facts discussed in the proceeding sections to synthesize a model for FECs soft money solicitation rules development, and discusses its fate at a local equilibriumwith particular emphasis on the lessons for practitioners. Section 1 The Regulation: Its Content, History, Development, and Progress.

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

In 2002, Congress, after much debate, passed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 200212 (BCRA). Among other goals, the BCRAs central purpose is to stop federal officials, candidates for federal office, and their agents from raising so-called soft money funds not subject to federal contribution limits13. Central to that purpose, the BCRA extensively and deeply amended the Federal Election Campaign Act of 197114 (FECA). In particular, the BCRA banned federal officeholders, candidates, and their agents from soliciting, receiving, directing, transferring, or spending funds in connection with an election for federal or non-federal office unless those funds comply with the amount and source restrictions in FECA15. Yet, despite this broad ban on the raising of soft money, the BCRA also explicitly authorized, under 323(e)(3), federal candidates, office holders, and their agents to attend, speak, or be a featured guest at a

12

Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107155, 116 Stat. 81 (codified

primarily in scattered sections of 2 and 47 U.S.C.).

13

Shays v. FEC, 414 F.3d 76, 79 (D.C. Cir. 2005) (stating purpose of BCRA as to rid American

politics of two perceived evils: the corrupting influence of large, unregulated donations called soft money, and the use of issue ads' purportedly aimed at influencing people's policy views but actually directed at swaying their views of candidates.); see also, McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93, 93, 100101 (2003) (delineating a triune purpose of the BCRA, including curbing the corruption or the appearance of corruption of federal candidates and officeholders by prohibiting federal officers from soliciting soft money donations).

14 15

Federal Elections Campaign Act of 1971, Pub, L. No. 92255, 86 Stat. 3, (1972). 2 U.S.C. 441i(e)(1)(A)(B) (2006)

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

fundraising event 16 of the kind at which they are banned from soliciting. These directives created an internal tension within the statute; the FEC issued rules to mediate the uncertainty. In attempting to reconcile these provisions, the FEC first promulgated rules in July 200217. The 2002 rules provided a complete exemption from the BCRAs general solicitation ban, on the condition that the candidate not be mentioned in the event publicity documents.18 Rep. Christopher Shays, who sponsored the BCRA in the House, challenged the regulations in Shays v. FEC (Shays I).19 The district court held that the regulations were not contrary to

Congresss intent, but failed to meet the justification requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act, and thus invalid20. In the wake of Shays I, the FEC justified the 2002 rule, after new hearings, but did not change the text of the rule. With the new justification, candidates could still speak without restriction or regulation, under a complete exemption from the solicitation ban. Rep. Shays again challenged the newly justified regulations; the district court also again upheld the newly justified rule21 . However, on appeal, the D.C. Circuit court reversed the

decision, and invalidated the total exemption from the solicitation ban22. Relying on the first

16 17

2 U.S.C. 441i(e)(3) (2006).

Final Rules on Prohibited and Excessive Contributions; Non-Federal Funds or Soft Money, 67 Fed. Reg.49064, 49108 (July 29, 2002). [hereinafter 2002 Final Rule]

18 19 20 21 22

Id. Shays v. FEC, 337 F. Supp. 2d 28 (D.D.C. 2004) [hereinafter Shays I] Shays I, 337 F. Supp. 2d at 9293 Shays v. FEC, 508 F. Supp. 2d 10 (D.D.C. 2007) Shays v. FEC, 528 F.3d 914 (D.C. Cir. 2008) [hereinafter Shays III]

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

prong of Chevron23 , the court noted that the FEC had created an exception where there was none before, and ran afoul of Congress clear intent to limit exceptions to the general ban24. The FEC, the court held, had overstepped its bounds. Into the new vacuum, the FEC began a new round of proposed rulemaking in December 2009.25 The Commission proposed three new varieties of the rule.26 The first proposal would surgically strike the offensive without restriction or regulation language, but leave the rest of the rule intact. The second variety was more holistic; it struck the offensive language, and broadened the scope of the rule to cover activities at any fundraiser not just state party functions. The third variety would also strike the offensive language, but would distinguish rules for state party fundraisers from rules covering all other soft money fundraising events. After a period of notice and comment, the FEC issued rules derived from the second variety. The Commission promulgated the rules on May 5, 2010. 27 Section II Darwinian Selection, Local Equilibriums, Complex Systems, and Administrative Action. Before we can begin to model, and to understand fully, the underlying reasons for the particular development of the soft-money solicitations regulations, we must train the lights which to that development. In this section, I provide an overview of the relevant conceptual

frameworks. This overview is in no way exhaustive, and is necessarily limited to those tools

23 24 25

Chevron v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 467 U.S. 837, 84243 (1984). Shays III 528 F.3d at 93334

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Participation by Federal Candidates and Officeholders at Non-Federal Fundraising Events, 74 Fed. Reg. 64016 (Dec. 7 2009)

26 27

Id. 11 C.F.R. 300.64 (2010)

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

which we need to utilize in our final analysis. In particular, this is an overview of the mechanism of Darwinian selection as applied to the law, the subsidiary concepts of local equilibria and stunted economy, the nature of complex system dynamics of which Darwinian selection is but one example, and the inherent nature of administrative rulemaking which places it surely and squarely within the overlapping purview of these theoretical frameworks. A. Darwinian Selection and the Law The Darwinian model of evolution by natural selection, with subsequent revisions, is the foundational and unifying theory of all biological science. Indeed, to speak of biologic theory before Darwins insight is to wax on a moot pointnatural selection is to biology what the big bang is to physics, the absolute and only starting point. Yet despite its comprehensive

explanatory power, the principle is actually a beguilingly simple one. Put succinctly, it says certain heritable mutations within a unit of selection enjoy advantages, randomly assigned through genetic variation, which allow for a differential rate of survival within a particular environments selective pressures and which thereby increase the occurrence rate of that certain heritable variety. Put simply, natural selection is the nonrandom survival of random mutation and variation as demanded by a particular environment. The best randomly adapted survive and thrive best. For this arational process to occur, three conditions must be met. First, the members of a species must vary in their morphology. Second, those variations must be heritable, i.e. the

variation of the parent must pass to the child. Third, the variations must affect the members rate of reproduction. Once these three conditions are metvariation, heritability, and survivability natural selection will inexorably occur within a population. The environment willwithout

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

concern for the particular individual, that is to say arationallybegin to select towards those variations which may survive within its confines. Despite, or more likely because of, the seeming simplicity of the theory, natural selection has a number of associated fallacies; two of these, in particular, plague legal application of the theory. behind. The teleological fallacy is the most frequent misstep, with the unitary fallacy close The teleological fallacy presumes wrongly that evolution is a perfection seeking

mechanism. This is not the case. Natural selection seeks only those forms which may survive a given condition, not those forms which would absolutely best survive all conditions. There is a reason trilobites have not significantly evolved for millennia; evolution leaves well enough alone. Alternatively, the unitary fallacy mistakenly assumes that there can be only one final result from natural selection, whether that result be the best or just well-enough. While the unitary fallacy runs parallel to the teleological fallacy, it is actually more myopic. It limits the

predicted result of natural selection to an absolute efficiency peak, and ignores the reality of local peaks and stunted economy. Despite the distinction, both fundamental fallacies, however, result from the same retroactive analytical lens. Because all evolutionary analyses are retroactive, they are predisposed toward both fallacies. Any use of the evolutionary model, then, must carefully guard against these two alluring and creeping missteps. Unsurprisingly, legal theory has, in time, fallen into both and slowly worked its way out of the mire. Since Darwins publication of The Origin of Species, and even before, those attempting to explain the law have been seduced by evolutions charm. Indeed, most early efforts to reach a total predictive model of legal development made some type of analogy, explicitly or implicitly, to the seemingly self-evident proposition that the laws development must be guided by the

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

fitness of a particular law or rule. Under the eloquent pen of Oliver Wendell Holmes, and the inventive intellect of John Henry Wigmore, and the creative ruminations of Arthur Corbin, the early evolutionary model took shape through a selective raiding of biologys revolutionary theory. These early efforts, though, were mere analogiesor perhaps more accurately metaphors which failed to strictly define their terms or mechanisms. They attempted to retroactively rationalize the laws development by explaining that the path of the law had been the only path with the law could have taken. The early literatures thesis, boiled down, was that the law developed as it has because it necessarily must have. This explanation, of course, fails to provide a useful predictive and falsifiable hypothesis, akin to a scientific hypothesis. These models lasted through the 1920s. Yet, the early models failure was in the teleological fallacy. They presumed that the development of the law meant the progress and the perfection of the law. Akin to their counterparts in the social evolutionary realmMr. Herbert Spencers Social Darwiniststhis scholarship missed a fundamental principle of natural selection: it does not demand the best overtake the well-enough. Whatever the path of a

particular law, or species, it is substantially unlikely that the surviving type is the objective best for a particular environment, or even for a society as a whole. Rather, the surviving type is simply good enough to survive consistently. Put simply, progression is not progress or

perfection, it is simply the skin-of-its-teeth surviving of permutation. [Transition] After a long, Legal Realism-dealt latency, the evolutionary model resurrected itself, selectively, in the 1970s Law and Economics movement. In the hands of Paul Rubin and

George Priest, and Robert Cooter and Lewis Kornhauser, and William Landes and Richard

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative Law and

Posner, the evolutionary theory was given, at the very least, predictive teeth.28

Economics great contribution was a predictive theorem: the law tends toward the most efficient solution because inefficient laws will, necessarily, generate more litigation and, coursed over many challenges, the law will become efficient regardless of the whims or wishes of the particular judge or jury. Here again, though, the proposed theory falls into a fallacy. Law and Economics fascination with the most efficient outcome should, theoretically, demand a convergence toward a single economically fastidious rule in every litigation issue. In other

words, Law and Economics ex hypothesi falls into the unitary fallacy. Of course, this is an absurd, and inaccurate, predictionas even the Law and Economics scholars now admit. However, leaving aside its weaknesses, the Law and Economics movement, despite its myopic use of Darwins idea, did make the long first step down the short road toward a helpful evolutionary legal model.

Section 3 Challenges to the Evolutionary Model; or, Why the Revised Evolutionary Model is Insightful, Instructive, and Necessary. Section 4

28

Ironically, and notable here, the development of the evolutionary theory within the legal system is, in fact, subject to its own evolutionary analysis. Its initial condition, in the early theories, is the speciation point. Its early refinements, its 50 year latent period, its explosion in the 1970s (a punctuated equilibrium if one has ever been observed), and its final adjustment in the late 2000s presents a perfectly traceable progression from a simple organism which responds to the selective pressures of academic rigor, and heritable variation and ancestry, towards a refined, survivable theory.

Brett Seifried

ALR Comment Narrative

What Does the Evolutionary Model Say about the Progress and the Fate of Soft Money Fundraising by Federal Officials and Candidates?

Вам также может понравиться

- Columbia Law Review Association, Inc. Columbia Law ReviewДокумент35 страницColumbia Law Review Association, Inc. Columbia Law ReviewKarishma RajputОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id4490965Документ29 страницSSRN Id4490965rph9jcjwwrОценок пока нет

- 73 Geo Wash LRevДокумент35 страниц73 Geo Wash LRevmagic lОценок пока нет

- Study Guide Module 1Документ16 страницStudy Guide Module 1sweta_bajracharyaОценок пока нет

- Posner - Law, Economics, and Inefficient NormsДокумент49 страницPosner - Law, Economics, and Inefficient NormsLoretoPazОценок пока нет

- Pao Law IrrДокумент39 страницPao Law IrrMelody May Omelan ArguellesОценок пока нет

- Nature of Judicial Review TheДокумент36 страницNature of Judicial Review TheThales MarrosОценок пока нет

- Capture Theory and The Courts - 1967-1983Документ81 страницаCapture Theory and The Courts - 1967-1983Jefferson DalamuraОценок пока нет

- Veil of Ignorance Rules in Constitutional LawДокумент35 страницVeil of Ignorance Rules in Constitutional LawLuis Patricio Garcia RamosОценок пока нет

- @@@law Coordination WeingastДокумент44 страницы@@@law Coordination Weingastenzo_coppolaОценок пока нет

- Whittington (2005) - James Madison Has Left The Building PDFДокумент22 страницыWhittington (2005) - James Madison Has Left The Building PDFMarcosMagalhãesОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law of Agenda ControlДокумент62 страницыConstitutional Law of Agenda ControlFrancisco Picón GutiérrezОценок пока нет

- The Many Faces of the Rule of LawДокумент24 страницыThe Many Faces of the Rule of LawHamza ButtОценок пока нет

- Legislation and Regulation OutlineДокумент60 страницLegislation and Regulation OutlineashleyamandaОценок пока нет

- Yale Law Rule of Recognition PaperДокумент34 страницыYale Law Rule of Recognition Paperchrisgoss1Оценок пока нет

- Black (2008) Constructing and Contesting Legitimacy and Accountability in Polycentric Regulatory RegimesДокумент28 страницBlack (2008) Constructing and Contesting Legitimacy and Accountability in Polycentric Regulatory Regimesbaehaqi17Оценок пока нет

- Oxford University Press Journal of Law, Economics, & OrganizationДокумент21 страницаOxford University Press Journal of Law, Economics, & OrganizationCaio RamosОценок пока нет

- On The Moral Status of The Rule of Law KramerДокумент34 страницыOn The Moral Status of The Rule of Law KramerSonsie KhatriОценок пока нет

- Scott J. Shapiro - What Is The Rule of Recognition (And Does It Exist)Документ34 страницыScott J. Shapiro - What Is The Rule of Recognition (And Does It Exist)Eduardo FigueiredoОценок пока нет

- The Forms and Limits of Adjudication AnalyzedДокумент58 страницThe Forms and Limits of Adjudication Analyzedn_es100% (1)

- UB Law Journal Article Explores Democratic Features of Common LawДокумент50 страницUB Law Journal Article Explores Democratic Features of Common LawrenatoarpcОценок пока нет

- Columbia Law Review Association, Inc. Columbia Law ReviewДокумент43 страницыColumbia Law Review Association, Inc. Columbia Law ReviewBhava SharmaОценок пока нет

- Future of State Sovereignty 2017Документ24 страницыFuture of State Sovereignty 2017Luca CapriОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id3053521Документ17 страницSSRN Id3053521igonboОценок пока нет

- Corporate Governance Law ZumbansenДокумент26 страницCorporate Governance Law ZumbansenRicardo ValenzuelaОценок пока нет

- Rule of LawДокумент64 страницыRule of Lawadom ManteОценок пока нет

- Yale Law Journal Company, IncДокумент36 страницYale Law Journal Company, IncDiogo AugustoОценок пока нет

- Error CorrectionДокумент39 страницError CorrectionAulia RahmanОценок пока нет

- Harts Concept of A Legal SystemДокумент34 страницыHarts Concept of A Legal SystemLeoAngeloLarcia0% (2)

- Constitutional Supremacy and Judicial ReasoningДокумент20 страницConstitutional Supremacy and Judicial ReasoningRoberto Javier Oñoro JimenezОценок пока нет

- The Culture of Legal Change, A Case Study of Tobacco in JapanДокумент79 страницThe Culture of Legal Change, A Case Study of Tobacco in JapanIndonesia TobaccoОценок пока нет

- Super StatutesДокумент62 страницыSuper StatutesAlexandre Fernandes SilvaОценок пока нет

- Waluchow 2007 Philosophy CompassДокумент9 страницWaluchow 2007 Philosophy CompassfvillarolmedoОценок пока нет

- Adr, Shimglina and ArbitrationДокумент29 страницAdr, Shimglina and ArbitrationMak YabuОценок пока нет

- Law As A Weapon in Social ConflictДокумент17 страницLaw As A Weapon in Social ConflictFelipe NogueiraОценок пока нет

- Justice and Legal ReasoningДокумент27 страницJustice and Legal ReasoningSiddharth soniОценок пока нет

- Judicial AuditingДокумент36 страницJudicial AuditingtalentaОценок пока нет

- C.R. Sunstein y A. Vermeule (2003) Interpretation and InstitutionsДокумент68 страницC.R. Sunstein y A. Vermeule (2003) Interpretation and InstitutionsRENATO JUN HIGA GRIFFINОценок пока нет

- Formation of Customary LawДокумент38 страницFormation of Customary LawHashimawati HashimОценок пока нет

- Capabilities and The LawДокумент17 страницCapabilities and The LawPantelis TsavalasОценок пока нет

- Justice and Legal ReasoningДокумент27 страницJustice and Legal ReasoningmartinsskylarОценок пока нет

- Sherwin.18-24.Modern Equity - CURRENTДокумент27 страницSherwin.18-24.Modern Equity - CURRENTZakariaОценок пока нет

- The Constitution MichelmanДокумент22 страницыThe Constitution MichelmanPablo AguayoОценок пока нет

- Public Policy Research Paper Series: University of Southern California Law School Los Angeles, CA 90089-0071Документ32 страницыPublic Policy Research Paper Series: University of Southern California Law School Los Angeles, CA 90089-0071horaciophdОценок пока нет

- Judicial Organization and AdministrationДокумент18 страницJudicial Organization and AdministrationlegalmattersОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 13.234.96.8 On Sun, 05 Sep 2021 17:42:36 UTCДокумент12 страницThis Content Downloaded From 13.234.96.8 On Sun, 05 Sep 2021 17:42:36 UTCsiddhant aryaОценок пока нет

- The Problem of Social Order: What Should We Count As Law?Документ12 страницThe Problem of Social Order: What Should We Count As Law?Wahyu JuniantoОценок пока нет

- Unit Objectives Learning OutcomesДокумент15 страницUnit Objectives Learning OutcomesAkash BaratheОценок пока нет

- Law Review: New York UniversityДокумент21 страницаLaw Review: New York UniversityKhallvina IzumiОценок пока нет

- The Expansion of American Administrative Law and the Safeguards of Public RegulationДокумент20 страницThe Expansion of American Administrative Law and the Safeguards of Public RegulationAmartya ChoubeyОценок пока нет

- M Tushnet, Alternative Forms of Judicial Review' (2003) 101 Michigan Law Review 2781, 2781-802Документ23 страницыM Tushnet, Alternative Forms of Judicial Review' (2003) 101 Michigan Law Review 2781, 2781-802humbertosoutonetoОценок пока нет

- Rule of LawДокумент29 страницRule of LawTamannaОценок пока нет

- Distributive and Paternalist Motives in Contract and Tort Law Wi-CompresséДокумент97 страницDistributive and Paternalist Motives in Contract and Tort Law Wi-CompresséYousra DoukkaliОценок пока нет

- Common Law and Economic EfficiencyДокумент48 страницCommon Law and Economic EfficiencyAnindya AnwarОценок пока нет

- Corporate PersonhoodДокумент47 страницCorporate PersonhoodgodardsfanОценок пока нет

- Democracy by Decree ReviewДокумент4 страницыDemocracy by Decree ReviewAnish SinhaОценок пока нет

- Waldron - The Rule of Law and The Importance of ProcedureДокумент26 страницWaldron - The Rule of Law and The Importance of ProcedurelonluviousОценок пока нет

- Mashaw Explaining Administrative ProcessДокумент33 страницыMashaw Explaining Administrative ProcessNitin PavuluriОценок пока нет

- Kina Finalan CHAPTER 1-5 LIVED EXPERIENCES OF STUDENT-ATHLETESДокумент124 страницыKina Finalan CHAPTER 1-5 LIVED EXPERIENCES OF STUDENT-ATHLETESDazel Dizon GumaОценок пока нет

- Schematic Electric System Cat D8T Vol1Документ33 страницыSchematic Electric System Cat D8T Vol1Andaru Gunawan100% (1)

- Whois contact details list with domainsДокумент35 страницWhois contact details list with domainsPrakash NОценок пока нет

- Product Life CycleДокумент9 страницProduct Life CycleDeepti ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- FI - Primeiro Kfir 1975 - 1254 PDFДокумент1 страницаFI - Primeiro Kfir 1975 - 1254 PDFguilhermeОценок пока нет

- Alsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualДокумент26 страницAlsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualJoão Francisco MontanhaniОценок пока нет

- Rainin Catalog 2014 ENДокумент92 страницыRainin Catalog 2014 ENliebersax8282Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 3Документ11 страницChapter 3Leu Gim Habana PanuganОценок пока нет

- Investigation of Cyber CrimesДокумент9 страницInvestigation of Cyber CrimesHitesh BansalОценок пока нет

- 6.variable V Variable F Control - Braking, Closed Loop ControlДокумент25 страниц6.variable V Variable F Control - Braking, Closed Loop ControlJanani RangarajanОценок пока нет

- Web Design Course PPTX Diana OpreaДокумент17 страницWeb Design Course PPTX Diana Opreaapi-275378856Оценок пока нет

- Booklet - CopyxДокумент20 страницBooklet - CopyxHåkon HallenbergОценок пока нет

- 14 Worst Breakfast FoodsДокумент31 страница14 Worst Breakfast Foodscora4eva5699100% (1)

- The Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerДокумент33 страницыThe Scavenger's Handbook v1 SmallerBeto TОценок пока нет

- Eurythmy: OriginДокумент4 страницыEurythmy: OriginDananjaya PranandityaОценок пока нет

- Navavarana ArticleДокумент9 страницNavavarana ArticleSingaperumal NarayanaОценок пока нет

- Climbing KnotsДокумент40 страницClimbing KnotsIvan Vitez100% (11)

- Monohybrid Cross WorksheetДокумент2 страницыMonohybrid Cross WorksheetLovie Alfonso0% (1)

- Colégio XIX de Março 2a Prova Substitutiva de InglêsДокумент5 страницColégio XIX de Março 2a Prova Substitutiva de InglêsCaio SenaОценок пока нет

- Eating Disorder Diagnostic CriteriaДокумент66 страницEating Disorder Diagnostic CriteriaShannen FernandezОценок пока нет

- Effective Instruction OverviewДокумент5 страницEffective Instruction Overviewgene mapaОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 - Programming of 8085 MicroprocessorДокумент32 страницыUnit 2 - Programming of 8085 MicroprocessorSathiyarajОценок пока нет

- 001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxДокумент2 страницы001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxTelle MarieОценок пока нет

- Design Thinking SyllabusДокумент6 страницDesign Thinking Syllabussarbast piroОценок пока нет

- Saic P 3311Документ7 страницSaic P 3311Arshad ImamОценок пока нет

- JDДокумент19 страницJDJuan Carlo CastanedaОценок пока нет

- Bell I Do Final PrintoutДокумент38 страницBell I Do Final PrintoutAthel BellidoОценок пока нет

- APP Eciation: Joven Deloma Btte - Fms B1 Sir. Decederio GaganteДокумент5 страницAPP Eciation: Joven Deloma Btte - Fms B1 Sir. Decederio GaganteJanjan ToscanoОценок пока нет

- Geraads 2016 Pleistocene Carnivora (Mammalia) From Tighennif (Ternifine), AlgeriaДокумент45 страницGeraads 2016 Pleistocene Carnivora (Mammalia) From Tighennif (Ternifine), AlgeriaGhaier KazmiОценок пока нет

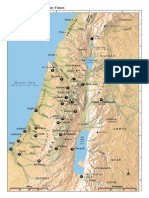

- Israel Bible MapДокумент1 страницаIsrael Bible MapMoses_JakkalaОценок пока нет