Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Efficacy of Interactive White Boards MEIT503 Sept 10 FINAL

Загружено:

junebaby74Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Efficacy of Interactive White Boards MEIT503 Sept 10 FINAL

Загружено:

junebaby74Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Making an argument: Examining the efficacy of Interactive Whiteboards and ancillary technologies in the Post-Compulsory context: What factors

are inhibiting adoption?

The

efficacy

of

Interactive Whiteboards

(IWBs)

in

post-compulsory

educational contexts is surprisingly unsubstantiated. There is a burgeoning body of research within the Primary and Secondary sectors, which examine the usefulness of these innovations in a variety of disciplines and age ranges, but there is no analogue within the HE and FE environments. Partially this is undoubtedly a

consequence of their being no strategic imperative on these sectors to roll out IWBs. Primary and Secondary schools received 25 million of funding specifically to equip classrooms with IWBs in 2004 (DfES 2004). Resultantly, within the UK, 70% of Primary and Secondary Schools are believed to have boards; No comparable data is available for the post-compulsory sectors, but penetration is currently significantly below this level.

This study will concern itself not just with the numbers, but also attempt to assay the perceived and potential pedagogic value of these boards, and ascertain the degree of training currently provided within the sector to facilitate their

successful use. As such it is a binary study; The first part of the essay will be predicated on my proposing a hypothesis, and the second part will focus on the construction and utility of a test mechanism to ascertain its validity. There may also

be specific cultural issues pertaining to the adoption and incorporation of these and

other technologies within the Higher and Further Education contexts, and these also warrant consideration herein. Hopefully the results of the survey will articulate any cultural and/or pedagogic issues which are impeding take up, but it is equally possible that with historically a far less proscriptive funding regimen, it is simply the case that HE and FE procurement priorities have been focused elsewhere. It is also my contention that in many cases HE Colleges are well equipped in terms of units, but as these were often installed without a commensurate training programme to express their pedagogic value and assuage staff anxieties concerning the utilisation of technology within their lessons, they are under used.

Additionally, in the incorporation of Classroom Technologies in HE there is typically scant consideration of the ways in which culturally the value of these tools can be demonstrated, resulting in the under use (and ultimately obsolescence) of expensively procured resources. BECTA, the body providing strategic advice on the procurement and utilisation of Classroom Technologies within the Compulsory and FE milieu advise that teaching staff can maximise the pedagogical impact of IWBs by investing time in training to become confident users, exploring the full range of capabilities of whiteboards and collaborating and sharing resources with other teachers(BECTA ICT Research 2003). As we will see, the extent to which this guidance is adhered to is variable across all sectors, and indeed negligible within the HE setting. I will consider some of the most prevalent models of change agency and diffusion of innovation in exploring ways of mitigating cultural resistance to the

adoption of IWBs and other Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) tools.

Firstly, a brief orientation in what Interactive Whiteboards are, and what they are for. To paraphrase the JISCs Briefing for Senior Managers in HE and FE, an IWB is a ..large physical display panel that can function as an ordinary whiteboard, a projector screen, an electronic copy board or as a computer projector screen on which the computer image can be controlled by touching or writing on the surface of the panel instead of using a mouse or keyboard (TechLearn 2005). They have a myriad of advantages over conventional whiteboards, not least the capacity to incorporate highly visual interfaces which communicate learning graphically and in real time, and utilising media that are often highly flexible and, crucially, interactive. As a very crude example, an IWB can display the rotation of an object in space in a way that simply isnt possible using chalk.

They afford the user the opportunity to manipulate on-screen data easily and effectively. Additionally, being digital media any interactions can be recorded and edited/amended afterwards, or made available to others in a variety of formats (e.g. presented online, e-mailed as a WMV file etc). They also allow teaching and support staff to easily and rapidly create customised learning objects from a range of existing content and adapt it to the needs of the class in real time. When combined with an ancillary technology like a Voting Kit, they allow the teacher to take and exhibit a snapshot of group understanding which enables the skilled facilitator the opportunity to amend the lesson in real time, allowing them to either remediate or develop interesting tangents. This degree of interactivity can also make a

traditionally didactic learning experience (like receiving a lecture) far less passive for the participant.

In the first instance, I will make a critical review of the literature available (overwhelmingly from research conducted within KS 1-4 contexts), then move on to review the strategic imperatives underpinning and incentivising the mobilisation of these units in the classroom. I will then analyse the results of a survey conducted with teaching and support staff in the post-compulsory (i.e. Further and Higher Education) sectors, and assess how cognate these results are with the experiences documented elsewhere. The survey will look at ways in which IWBs (and

associated classroom technologies) are currently being utilised, and assay the perceived pedagogic benefit within these environments. The survey will be made available as both a web-based tool (using a piece of proprietorial software called Survey Monkey) or in a word document issued via e-mail; It will be disseminated to all pertinent lists chronicling HE and FE support networks covered by the JISC Regional Support Centre South West.

Within the KS 1-4 milieu, research indicates perceptions of the effectiveness of IWBs varies considerably, as does discernible impact of their use (quantified via the possibly spurious indicator of SATS results). Rollout of the boards themselves is piecemeal, and largely dependant on the funding source (Glover and Miller 2006), but the degree to which IWBs have been assimilated into teaching is broadly considered to be negligible. In Secondary Schools for instance, the introduction of IWBs has led to significant pedagogic change by some technologically competent teachers in some secondary schools but there is a marked difference in the pace of change from school to school(Glover and Miller 2006).

This could be because Teachers within this particular sector have not received sufficient training, or, as McCormick & Scrimshaw indicate, it may be that staff are not sufficiently acculturated into the broader potentialities for pedagogic amelioration offered by IWBs and other classroom technologies (McCormick and Scrimshaw 2001). As Glover and Miller again point out, ..potential may not be realised unless technology is more than an aid to efficiency, or an extension devicePedagogic change is necessary so that the technology becomes a transformative device to enhance learning(Glover and Miller 2006). Particularly in respect of IWBs, it can be posited that in order for these technologies to be fully utilised as learning and teaching media, teachers need to fully appreciate the opportunities for interactivity and collaboration offered. IWBs have the capacity to be much more than passive presentational devices; They can become active conduits for high quality, mutual learning experiences. Beeland corroborates this assertion by remarking in his study of Secondary age pupils that ..school and technology leaders need to be aware of the potential these whiteboards have for increasing student achievement through increased student engagement(Beeland 2001).

It is noteworthy therefore that in the guidance given with Circular 173/2004 (Interactive Whiteboard Initiative for Primary/Secondary sectors sponsored by the then Department for Education and Skills) such advice as was provided on the utility of these innovations was entirely mediated towards whole class delivery: When using this technology the emphasis is on effective whole class strategies, including teacher modelling, exposition and demonstration, prompting, probing and promoting

questioning, class discussions managed by the teacher, opportunities to predict, test and confirm and bringing the class together to reinforce key points emerging from individual and group work. It is the use of these effective teaching strategies alongside the use of the interactive whiteboard that results in the greatest gains(DfES 2004). This assertion is not substantiated in the call by any references to indicative research, and surely presents a rather solipsistic view of the potential of IWBs, negating at a stroke their capacity to facilitate and enhance small group work, or even work with individuals.

In their study of the use of the IWB in Literacy lessons within the Primary classroom, Smith et al. suggest a link between students physical interaction with the board and opportunities for interaction and discussion and assert that teachers may need to consider how this can be achieved (Smith 2006); In other words, if the incorporation of IWBs is to foster a higher degree of teacher-pupil and pupil-pupil interaction within the classroom, teaching staff need to develop a new approach to pedagogy which is predicated on the degree of access students are allowed to the hallowed board itself. If implemented, this would represent a major cultural shift, away from a Sage on the Stage delivery style, to a Guide on the Side model, with teachers facilitating a more Socratic dialogue in the classroom, contingent on a degree of discourse predicated on pupil interaction with the IWB. Ostensibly at least, this appears antithetical to the prior DfES covenant, which enshrines the teachers role in the established didactic and transmissive mode, delivering facts to passive classroom recipients.

This perspective is not consistent with the fundamental principles of education espoused by such luminaries as Vygotsky and Bruner, whose theories of cognitive development focus pre-eminently on the idea that social interaction defines the learning experience. Vygotskys concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is also predicated on the notion that social interaction is obligatory for successful learning to take place. The ZPD is the level of development than can be realised when children (he didnt extend his theory to adults) connect socially, predominantly with their peer group but also with adult teachers: "Every function in the child's cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological). This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals." (Kearsley 2009) This constructivist view of learning is refined by Vygotsky from ideas first postulated by his predecessor Jean Piaget, whose theory of genetic epistemology encapsulated the view that the edifices on which cognition where built (assimilation and accommodation) where contingent on ..a constant effort to adapt to the environment through social interaction (Kearsley 2009). More recently, Jerome Bruner has contributed to this school of thought through his writings on Instructional Design which, although divergent in the sense that he has no adherence to the concept of stage learning postulated by Piaget, concur with the idea that social interaction and dialogue are essential; Learning is an active process, in which learners construct new ideas based on their current level of understanding in collaboration with their contemporaries.

Other academics have developed theories of interaction for the Digital age which transcend the teacher-pupil/pupil-pupil paradigm. Michael G Moore for

instance is the progenitor of a three stage model which also incorporates LearnerContent Interaction. Moore asserts that this is the mode of delivery wherein most Adult education resides. This is the mode where learners talk to themselves, and without it there cannot be education, since it is the process of intellectually interacting with content that results in changes in the learners understanding, the learners perspective, or the cognitive structures of the learners mind. Historically this type of interaction has defined the distant learning experience, although it could be argued that in the new milieu of refined web technologies such as VoIP or Web Conferencing, this is no longer the case. Whilst this mode of interaction is not

unique to the modern epoch, modern classroom technologies such as IWBs have ramifications for this interplay. Moore contends that ..Educators need to organize programmes to ensure maximum effectiveness of each type of interaction, and ensure they provide the type of interaction which is most suitable for the various teaching tasks of different subject areas, and for learners at different states of development. Although this excerpt is from an essay focusing on contact modes within the realm of distance education, it is very much applicable to the pedagogical choices modern educators should consider (Moore 1989). More recently, the

concept of learner-interface interaction has been posited. Theorists of this school argue that a students skill with the communication medium..is positively correlated with success in that course. In order to gain any meaning from the course content, the students must be literate in the communication mediums rules of

interaction(Kelsey and Dsouza 2004). This assertion may seem self evident, but the resulting dynamic faces two ways; Students need to enhance their learning

literacies to engage most effectively with incipient media, but staff also have an obligation to avail themselves of suitable knowledge and skills to effectively address the varying learning needs and aptitudes of their students.

It may be that the true worth of IWBs will not be realised (or realisable) until this cultural shift is actuated. This will be a long struggle, as their still appears to be a perception that technology constitutes a threat rather than an opportunity; in the words of John and Wheeler, ..a Trojan horse designed to destabilise conventional teaching and deprofessionalise them (John and Wheeler 2008). Within the Primary and Secondary School environment, John and Wheeler stratify teachers into 4 categories which encapsulate the diversity of reaction to the incorporation of Technology. These (in ascending order of keenness!) are Enthusiasts, Pragmatists, Traditionalists and Refuseniks. Evidently, Enthusiasts attempt to fully integrate

new technologies into their teaching; Pragmatists recognise the potential of technology and seek an accommodation with it; Traditionalists recognise the latent potential of ICT but can perceive it as a threat to their professional knowledge and identity. Finally, Refuseniks, as the name suggests, ..are so critical of new

technology and teachers possible dependence on it that they resist its use and refuse to engage with its pedagogical potential. A BECTA study in 2004 (Jones 2004) articulated clearly some of the common barriers to cultural change in the incorporation of classroom technologies, and I would wager that many of the reasons cited correspond with reasons cited in Higher and Further Education; Hopefully the survey results will elucidate further.

The reasons for resistance to acculturation cited in this report are primarily Lack of confidence, Lack of competence, Lack of Technical Support and Lack of time. Teachers apparently often perceive students to possess more familiarity and proficiency in the use of technology than they exhibit, and resultantly believe this diminishes their perceived professional competence in the eyes of their pupils. This may be down to specific and highly contemporaneous issues pertaining to the accretion in inter-generational digital acculturation suggested by Mark Prensky. Prensky believes that .. as a result of this ubiquitous environment and the sheer volume of their interaction with it, todays students think and process information fundamentally differently from their predecessors. These differences go far further and deeper than most educators suspect or realizeit is very likely that our students brains have physically changed and are different from ours as a result of how they grew up (Prensky 2001). In other words, the population can be

quantified in terms of Digital Immigrants (i.e. those who did not grow up interfacing with a panoply of ubiquitous digital technologies) and Digital Natives (i.e. those who did!), and the single biggest problem facing education today is that our Digital Immigrant instructors, who speak an outdated language (that of the pre-digital age), are struggling to teach a population that speaks an entirely new language(Prensky 2001).

Its easy to be seduced by the solipsistic logic of this logic of this argument, but some recent evidence has suggested that in a scholarly context, although students are comfortable with technology, they dont necessarily know how best to apply it, or how to use it to maximum utility outside of a narrowly circumscribed personal/social agenda. For instance, the JISC Information Behaviour of the

10

Researcher of the Future report scrutinized the

web skills of the Google

Generation (analogous to Prenskys Digital Natives) and found that in actuality young learners lacked the critical and analytical skills required to assess the academic veracity of the information that they find on the web. Whilst they

possessed the basic searching skills and demonstrated confidence and familiarity with Computers, they had apparently not been schooled in critically assaying the plethora of materials available; Given the exponential proliferation and dubious provenance of many such allegedly academic materials on the web, the report further concluded that ..young people are dangerously lacking information skills. Well-funded information literacy programmes are needed, it continues, if the UK is to remain as a leading knowledge economy with a strongly-skilled next generation of researchers (JISC 2008). There are also those who disparage Prenskys concept of Digital Nativitism; Some of the grandiose claims made in his discourse are repudiated by Mark Bullen, who contends that ..the digital native or net generation discoursepresents a simplistic and superficial picture of an entire generation and ignores the complexity of technology use and its relationship to context (Bullen 2009). Bullen and others cite as a criticism the lack of evidence Prensky has

accumulated to substantiate these assertions.

What I am endeavouring to assert here is that whilst it may appear superficially manifest, there is not necessarily a disconnect between the teachers skills and the students requirements. If teachers cultural resistance to technology is predicated on fear of losing face, this is doubly unfortunate, as clearly HE and FE staff are well versed in the skills students need in spades if they are to utilise technology as a conduit to self-facilitated learning, although not necessarily within

11

the digital domain; If they could be encouraged and supported in utilising IWBs and other technologies to support students in developing these skills, they would be addressing an identified gap in student competence. The BECTA report also

highlights a lack of time and technical support being an impediment to take up of ICT; BECTA suggests that this could be facilitated by support staff being skilled at understanding and imbuing pedagogy as well as providing purely technical assistance i.e. being Learning Technologists rather than Technical Support staff. Within the HE context, Learning Technologists are already in post at a Faculty and/or Departmental level, so research may indicate that to some extent these problems are ameliorated; In practice however, there are often too few Learning Technologists in post to support staff intensively enough in the use of technology and the development of apt materials. Evidence from BECTA and elsewhere (e.g. Cuban et al 2001)further suggests that staff within the compulsory sector have not been granted sufficient time in which to familiarise themselves with Classroom technologies, and whilst teaching time is less of a burden within Higher Education( but probably not Further Education, where contact time is still roughly double that in HE at 25 hours per week), other pressures (e.g. research) are in the mix.

The recent report commissioned by JISC and the Higher Education Academy, Higher Education in a Web 2.0 world(JISC 2009), reiterated the need for staff to develop confidence and familiarity with technology. Commensurate with earlier

evidence reported above, it also signposts the critical priority of imbuing learners with appropriate Information Literacies for the modern age. It emphasised that staff in HE institutions need to continue to reflect on research into learning so that they are able to make fully informed choices about their teaching and assessment methods; In

12

other words, time to reflect on the ways in which technological incorporations can revise and enhance their approaches to teaching and learning. It also restated the need for HEis to support staff to become proficient users of an appropriate range of technologies and skilled practitioners of e-pedagogy, incorporating both into initial staff training and CPD programmes. This includes Senior Management Teams; Research indicated that organisations like the Leadership Foundation could be involved in developing staff in the full range of new technologies in their senior management development programmes. The report also suggested that teaching

staff could use technology to facilitate a new relationship which students, contingent on a more mutualised exchange which Web 2.0 technologies can expedite.

As previously referenced, Glover and Miller from Keele University conducted a study in 2006 to ascertain the extent to which Secondary School teachers recognised the pedagogic potential of IWBs. There study suggested that

pedagogically the technology is underdeveloped and underused, and these deficiencies were contingent on a number of factors, both pragmatic and conceptual; Physical access to the boards (and time spent rehearsing with them), and staff attitudes to these and other classroom technologies. Cognate with Rogers Diffusion of Innovation Model, there were some Missioners (or early adopters, to employ Rogers vernacular), but the majority of staff were either Tentatives or Luddites. This correlates with Rogers model, where Innovators and Early adopters constitute the minority, the majority are somewhere in the middle and there are a significant contingent of Laggards who are highly resistant to engagement. Laggards in this instance are those who see the role of IWBs as purely transmissive tools, effectively serving as a refinement of the traditional black/white board, whilst

13

Innovators (or Missioners) are seen as being committed to infusing and enthusing their peers with a readiness for the cultural change that they see these technologies catalysing. Rogers suggests that the mobilisation of Innovators/Missioners is

imperative in the broader adoption of new technologies, as they are the most instrumental in the success or failure of a new idea.

Knowles theory of Andragogy may also provide some answers relating to a lack of engagement on the part of staff. Herein Knowles uniquely proposes a theory of learning which pertains specifically to adult learners; Teachers and support staff in the context of this analysis. Andragogy has been disdained by some writers as stating the obvious, in that it starts from the assumption that adults are self-directed and expect to take responsibility for decisions. Essentially, this means that

instruction for adults needs to focus more on process than content, as the principle is driven by four assumptions: That Adults need to know why they need to learn something, that they need to learn experientially, that they approach learning as problem solving, and that they learn best when the topic is of immediate value. In Knowles words, ..any experience that they (adults) perceive as putting them in the position of being treated as children is bound to interfere with their learning. (Atherton 2010). Knowles has his fair share of detractors, but if we consent for the sake of argument to the concepts he espouses, they merely accentuate the possibility that Teaching staff are not engaging with the IWB (or Classroom Technology) agenda because they have not had the benefits explicitly articulated to them within their professional practice. Also, learning experientially contextually translates to using technology in teaching practice, and there are obviously risks entailed in exposing oneself publicly to possible failure in front of students.

14

What is striking in reviewing the research literature pertaining to the use of IWBs in the Primary and Secondary Classroom is the lack of data. Many papers dont seem to be contingent on a rigorous methodology; Much of the evidence presented is anecdotal, in the form of interviews and/or questionnaires. This paucity of hard evidence is highlighted in the review of literature from 2005 conducted by Smith, Higgins, Wall and Miller, and seems to persist today. There is very little quantifiable proof to corroborate claims that attainment and progression within the compulsory educational sphere have been predicated on the incorporation of Interactive Whiteboards and associated technologies. Interestingly, some

researchers are presenting a more nuanced appreciation of IWBs and their role within the visual culture potentially permeated by the adoption of classroom technologies.

In his 2008 study, Reedy asserts the possibility that these visual technologies may imply a certain type of classroom teaching, restricting negotiated discourse and entrenching the teacher as the authoritative presenter of fact, rather than as a guide and facilitator who utilises the technology to intercede between students and a body of knowledge. The pre-eminent technologies (cited as the IWB, Data Projector and PowerPoint) can combine to encourage a particular sort of presentational mindset that could be beginning to shape the classroom experienceeven though both students and teachers recognise that (they) can potentially discourage complex thinking, reasoning, and writing, and can encourage pointless animation and ostentation(Reedy 2008) . Other authors (e.g. Edwards et al 2002) have suggested that the interactive presentational features of IWBs can enhance the learning

15

experience in lessons like Mathematics, where the teacher can vividly display concepts such as rotation and transformation of angles in real time. The problem may reside not with the IWB, but with the institutional/sectoral culture, which does not encourage Teaching staff to fully explore the potential of ICT to emancipate students from a didactic, Chalk and talk style delivery mode; Reedy suggests that a lack of staff development meant that Secondary School teachers in his study did not recognise, or feel comfortable in utilising, the interactive features of the boards, and resultantly mass disengagement ensued, with the primacy of the limitedfunctionality IWB over the traditional board (leading) to some teachers rejecting the technologies altogether(Reedy 2008). This appears to be a dishearteningly

common experience, and it will be interesting to see if its mirrored within the contemporary HE/FE setting.

Interestingly, a survey conducted by the University of Newcastle in 2004 suggested that in Years 5 and 6 (KS2) Mathematics and Literacy based courses, a very significant volume of IWB resources had been created or adapted (58% of Maths lessons using IWBs and a whopping 67% of literacy lessons using IWBs) (26). It will be interesting to see how this corresponds with the HE and FE There are a plethora of free resources available for IWBs within

experience.

Primary/Secondary education (e.g. IWB.org, KentEd), many replete with lesson plans etc, although there are no non-commercial equivalents in the HE/FE sectors. The availability of free resources may account for the degree of take up/adaptation within these communities.

16

As Ive mentioned elsewhere, there is limited research into the impact IWBs have had in Further and Higher Education. One of the most significant instances is from the BECTA funded ICT Test Bed project, which was commissioned by the DfES in 2002 to explore how ICT could be used to support the Governments wider agenda for education reform. 34 million pounds was made available to a range of providers in areas of relative socio-economic depravation, including 3 FE Colleges. The Key findings report published in 2007 found that the incorporation of ICT had a positive impact on pedagogy, but more specifically, that The interactive whiteboard is recognised as a major innovation, with many lecturers commenting positively on the impact of the whiteboard on their classes. As a consequence there is growing dependence on IWBs, and several tutors commented on the difference it makes to their teaching, to the ambience of the classroom and to the motivation of the learners(BECTA 2007). Obviously the research was attenuated to focus

specifically on the impact of classroom technologies within areas of relative poverty, but it will be interesting to see how these reflections correlate with the perceptions of staff in this survey.

One explanation for resistance to the adaptation and incorporation of IWBs and other classroom technologies in an HE environment could be the present lack of effective Change Agents. Change Agents are those key individuals within an

organisation who are charged (either of their own volition or by management) with initiating, managing or implementing change. As drivers for change, they will need to generate impact within an organisation; This means they need to have a purchase on the trust, commitment and good will of their colleagues. Caldwell points out that in driving change, the role of Managers is peremptory-In an analysis of traditional

17

models of Change agency, they are expected to encourage commitment and empower employees to be receptive to change and technological

innovation(Caldwell 2004). There have been a multiplicity of theories of Change Agency, and in Caldwells review of the literature on these models, he identifies four essential theories.

Classifying Change agents as ..an internal or external individual or team responsible for initiating, sponsoring, directing, managing or implementing a specific change initiative, project or complete change programme, he goes on to define the types as Leadership, Management, Consultancy and Team based approaches.

These are broad and heuristic definitions, but nonetheless present a useful edifice from which to consider the role of change agents pertaining to the incorporation of ICT in the FE and HE classroom. Examining each in term, the Leadership model focuses on the necessity of Leaders being identified and visible as the primary motivators for and advocates of change; They envision, initiate or sponsor strategic change of a far-reaching or transformational nature. Within HE, Senior Managers have not historically been especially engaged with the TEL agenda; Understandably, their strategic decisions are primarily contingent on financial considerations, and whilst there are fairly significant funding streams open to HE for TEL initiatives from HEFCE (usually dispersed via JISC), these are often oriented towards research. Additionally, the sector is not privy to the same dictats on strategy that either bless or curse the compulsory sectors (and the FE sector to some extent).

Resultantly, whilst there are undoubtedly residual enclaves of enthusiasm for the incorporation of pedagogically sound TEL within HE Senior Management teams,

18

these are few and far between; apocryphal promises of dramatic cost savings from eLearning turned to ashes in the wake of the failed e-Universities UK initiative, and since then Senior Managers have generally complied with the HEPI recommendation that the future of e-learning in the UK lies in the need for a bottom-up development of blended learning within departments inside our HEIs(Slater 2009). Within the FE environment, where there have been significant funding initiatives mediated via the Learning and Skills Council to incorporate Classroom Technologies (including IWBs), there is data which evidences reasonable support for adoption. For instance, when questioned, 43% of FE teaching staff felt that their College Principal was a vocal advocate of e-learning and a further 42% felt that there were strong ICT champions at senior management level. These scores signify reasonable interest in incorporation at senior levels, but could be construed as disappointing given the concomitant (and some would say disproportionate) focus on funding and strategy directed at ICT within the sector since 1999 (the period this survey considers). However, the same census group perceived that ICT was driven

forward by department heads in only 7% of colleges and was the domain of small groups and enthusiasts in another 7%. This information is available in a report commissioned by BECTA in 2006 to assess the FE sectors engagement with technology (BECTA 2006) To date, there has been no analogous survey of Senior Management perceptions in HE, so this is difficult to quantify empirically.

In a statement that would seem to corroborate the requirement for change agency to be incorporated within HE, the report also asserted that..the human infrastructure that was the most important part of e-learning strategies within HEIs not the technology. Therefore it is essential that academics (have) ownership of

19

progress in e-learning within their departments and key individuals (are) given the opportunity to drive things forward. Subsequent HEFCE guidance on TEL has

reiterated the focus on winning Hearts and Minds, rather than focusing on the tools. Their most recent strategy, Enhancing learning and teaching through the use of Technology(HEFCE 2009) emphasises the pre-eminence of institutional strategies and contexts, and concentrates on how institutions can enhance learning, teaching and assessment using appropriate technology in a way that is suited to the underlying infrastructure and practice of the institution. This mode of change would ostensibly appear to be consistent the model identified by Caldwell as the Management Model, wherein ..Change agents are conceived as middle level managers and functional specialists who adapt, carry forward or build support for strategic change within business units or key functions.

Within the FE environment, this type of role has been historically funded and performed by assigned e-Learning Champions, selected via a rigorous and extensive application process and trained and funded (i.e. having their time bought out) by the Learning and Skills Council. Consequently, 66% of Colleges identified in the BECTA survey cited above were able to offer support from these Change Agents (who were all drawn from within the roster of Teaching staff already resident within the Institution) to other staff, and contingent on this, 80 per cent of colleges were able to offer staff development programmes to support staff who wished to develop or adapt e-learning materials. Whilst there is no central fund or guidance available for

equivalent positions in Higher Education, Individual Institutions and consortia have developed similar roles. For instance, in Scotland, a variety of HE institutions have come together to remodel there assessment practices, incorporating technology to

20

steer them away from didactic exam based adjudications and make them more cognate with student expectations and the demands of lifelong learning. Within the JISC funded REAP project, e-learning champions drawn from the six disciplinary divisions are appointed, and supported by e-learning specialists, to work with core module teaching teams to review and re-engineer assessment practices (Nicol 2007).

Whilst the work of champions as proselytisers for change has undoubtedly been effective in some instances, a note of caution is sounded by the Australian Flexible Learning Network, who suggest in their report The impact of eLearning champions on embedding eLearning that ..Champions of e-learning cannot alone embed e-learning in their organisation, industry or community. To sustain e-learning, managers and policy makers must assist and build organisational cultures and work processes that support innovation and the work of e-learning champions(Jolly et al 2009). This suggests that, cognate with the earlier HEPI and HEFCE guidance on the pre-eminence of people in informing cultural change, it is necessary for management to buy in to the credo of TEL; There also needs to be a recognition that whilst technological innovation often appears to accelerate exponentially, people move more slowly, and cultural change can subsequently appear glacial by comparison.

Within his 4 model conceptualisation of Change Agents, Caldwell also suggests a Consultancy model, wherein change agents are conceived as

external or internal consultants who operate at a strategic, operational, task or process level within an organisation, providing advice, expertise, project

21

management, change programme coordination or process skills in facilitating change. Within a HE context, the best recent exemplar of this model in the UK were the HE Academy funded Benchmarking and Pathfinder programmes. In the first instance, HEis were able to bid for funds to assess their current TEL provision (not just in a Learning and Teaching context, but in all associated processes) using a variety of different methodologies. The results did not provide the Institution with a Benchmark per se (i.e. a yardstick score with which they could compare their relative performance against other Institutions); Rather it gave every tier of staff within the organisation the opportunity to map their current perceptions of their competence and utility with ICT. The exercise was consultant led, with the Higher Education Academy funding the allotted hours for the consultant to facilitate the process.

At the end of the Benchmarking round, participating institutions were invited to bid for additional funding to become Pathfinders by exploring an area of innovation in Technology Enhanced Learning where strengths (or weaknesses) were identified in the previous phase . According to the HE Academy website, ..Projects focussed on new ways of using and embedding e-Learning, with a view to organisational change (Outram 2005). Again, this was consultant led and HEA funded. At the end of both phases, reports were made publically available, enabling the entire sector to draw upon the collective experience. Consultants engaged in the process worked at a strategic, operational, task and process level to canvas opinion, inform judgment and predicate avenues of future development, acting as change agents to mobilise remedial action at all levels. The HEA vision was that not only would these individual projects initiate change within individual institutions, they would also engender a cultural change across the entire sector by clearly demonstrating the benefits of

22

technology in teaching and learning and associated processes via trusted and verifiable research methods.

Sir John Daniel, formerly Vice Chancellor of the UKs Open University, posits a model of diffusion of innovation which could potentially expedite the task of change agents. Drawing on work by Moore (1995), he uses the euphemism of a Bowling Alley to articulate a theory for inculcating cultural change. Within this metaphor, an institution moves from limited to full adoption of technology by knocking over pins of niche interest and applicability which facilitate broader cultural acceptance by demonstrating value within the wider professional environment. If successful, they also create pockets of advocacy which should allow innovation to percolate more widely. Daniel emphasises that selecting the right niches (or pins) is critical in the first instance; ..They should be areas where the new technology can make a real difference, giving them a compelling reason to adopt it(Daniel 1998). Additionally, the niche should not be so large as to overwhelm the organisation, and some thought should be given to the potential knock on (meant literally if we are embracing the bowling metaphor!) of these niches, i.e. ..some thought should go to ordering the pins so that knocking over one bowling pin increases the chances of knocking over the next(Daniel 1998). Whilst this niche based focus is necessarily focused on relatively esoteric areas of work or interest, outcomes should be sufficiently generic to demonstrate broader transferability to other prospective

paradigms; ..it should not customise each application so much that synergy with future niches is lost(Daniel 1998).

23

If we apply this hypothesis to a consideration of Interactive Whiteboards and associated classroom technologies, traditionally there has not been a great deal of consideration given within the HE context from Management to demonstrating and disseminating the value of such tools. Generally, Institutions tend to either take a Big bang approach, where they make mass procurement and provisioning decisions without considering small scale inter-organisational dry runs, or individuals make purchasing decisions within departments or faculties predicated on the enthusiasm of early adopters without formalising conduits for their experiences to be formally recorded and disseminated more widely.

There is also limited research into the capacity of IWBs to integrate effectively with coupling technologies such as Voting Systems. These units increase the

interactivity of the learning experience by enabling students to signify their beliefs or indicate their preferences during a lesson. The advantage of synergising these

technologies is that the IWB gives the teacher the opportunity to display student perceptions in real time; Resultantly, they are able in theory to adjust their lessons to react to any misperceptions and/or interesting tangents that these votes produce, or they can have renewed confidence in the belief that there lesson is on target. Votes can also obviously precipitate conversations, facilitating learning and allowing for a less formal, didactic delivery and more of a Socratic dialogue. There is little evidence of the use of Voting Kits in conjunction with IWBs in Higher and Further Education environments, but there is a significant body of research within the

Primary/Secondary sectors which warrants consideration.

24

What literature there is in the HE domain suggests the need for training and awareness raising of the potentialities of these media amongst students and staff (Mller et al, 2006). A JISC Sponsored study from the University of Hertfordshire found that ..The level of interaction between students and tutors has increased significantly and students recall of information has improved as a consequence of the utilisation of an in-class voting system, and that ..tutors and students enjoy the face-to-face sessions now freed from the chores of delivering and receiving knowledge, both are able to interact more freely and put learning and teaching more closely to the test. Tutors are, as a result, finding out more quickly (rather than too late) what needs attention, and their teaching becomes correspondingly contingent (JISC 2009). As an adjunct to the main thrust of the survey, I will be including a question which considers the utility of Voting Kits and other sister technologies to IWBs (e.g. Mimios, Personal Tablet Boards) in the target sectors. Within the

primary and secondary sectors, research conducted indicates that the combined utility of these technologies has resulted in increased interactivity by facilitating the progress of students from being passive recipients of information to active participants in class, although the level of interactivity is queried.

In their critical review of the literature previously referenced, Smith, Higgins, Wall and Miller suggestion that although perceptions on IWBs seem resoundingly positive, there is very little quantitative evidence of the actual impact of their use on attainment or achievement. This is sadly consistent with some of the claims for these and other classroom technologies sporadically offered by politicians, who are inclined to make reckless statements that appear largely unsubstantiated (e.g. the assertion by then Education Secretary Charles Clarke in 2004 that ..Whiteboard

25

technology is really motivating pupils to learn, and can ..Create a more personalised Education system and most startlingly that ..(ICT) in schools could help improve GCSE results by "half a grade" if used properly)(BBC 2004). Other researches echo the concern that whilst policy makers and manufacturers have made heady claims for these units, there is currently little examination of their impact on pedagogic practices, communicative processes and educational goals (Gillen et al, 2007).

It is my contention therefore that, having critically analysed the research, there are a number of reasons why take up of IWBs and associated technologies has been relatively limited within the HE environment. In the first instance, as we have seen, HE institutions have a great deal of autonomy with respect to spending. Historically, Universities have enjoyed tremendous independence relative to their counterparts in the compulsory sectors, wherein the funding bodies interpret government policy via prescriptive dictats on spending priorities, often centrally or regionally procured, with all the attendant cost benefits. Whilst the Higher Education Funding Council provide strategic advice, the majority of their funding is contingent on student numbers and research, and HEis have comparatively great discretion in allocating these monies. Also, unlike in the compulsory sectors where Institutions are subjected to a rigorous and independent quality assessment via OFSTED, areas of inspection for the Quality Assurance Agency (the body responsible for Quality Assurance in Higher Education) audits are negotiated with the Institution in advance of the assessment, and therefore HE Organisations are not expected to comply with a universal range of standards as establishments in the compulsory sectors are.

26

Indeed, the QAA has recently been subjected to criticism from the House of Commons Select Committee on the HE sector, which deemed the Agency to be focused ..almost exclusively on processes, not standards; Furthermore, the committee called for the QAA to be disbanded and replaced by an independent Quality and Standards Agency, more analogous in remit to OFSTED. The damning consequence was that the HE system lacked consistent national standards and this had spawned a culture in HE Senior Management where Vice Chancellors were unable to present the committee with ..a straightforward answer to the simple question of whether students obtaining first class honours degrees at different universities had attained the same intellectual standards (HoC 2009). This has meant that within sectors where a rigorous QA regimen has been in place, funding streams have been allocated not just for the procurement of technology, but provision has also been made (in principle at least) for staff to be acculturated into adapting these technologies into their working practices via training and staff development. This had been actuated via the creation of Champions, evidenced above within the FE sector and funded via national initiatives (e.g. by BECTA for multiple roll-outs of e-Learning resources under the auspices of the National Learning Network Materials programme). There is no analogue of this approach within the Higher Education milieu, and resultantly, I assert that, along with a plethora of other classroom technologies, IWBs are not being exploited to full pedagogic potential as a consequence of poor or non-existent peer-supported acculturation.

27

Understanding the Use of Data:

A Survey of the perceived deployment and effectiveness of Interactive Whiteboards and Associated Technologies in the Post-Compulsory Environment:

The survey itself is consists of 10 multiple choice and 3 free text questions, in addition to collecting the basic, pre-requisite information required (e.g. name, role in organisation etc). It is designed to elicit responses which qualitatively inform my understanding of the present pedagogic role of the IWB in a post-compulsory context, as well as providing quantitative data on the logistical aspects of their use (e.g. where they are located, how many of them are available, how often they are used etc). Resultantly the multiple choice questions generally capture quantitative data (e.g. how often are they used, what size of class do you teach with them), whereas the free text questions will hopefully educe more qualitative information (e.g. has provision of an Interactive Whiteboard changed the way you teach? or Are you aware of any internal/external sources of pedagogical support for the utilisation of IWBs within your teaching and learning?). The purpose of the survey is two fold. Firstly, I am interesting in landscaping the current level and context of usage of these technologies in Higher and Further Education in the South West, and making reasonable extrapolations as to trends and congruency with national trends identified elsewhere. Secondly, I hope to use the quantative data to support my previous assertion that a lack of practical support for adoption of these technologies in Higher Education has resulted in a deficiency of appreciation of their pedagogic

28

value, and a concomitant lack of take up. I would aspire therefore to derive both inductive and deductive conclusions to confirm and construct hypotheses.

The survey was made available to Higher Education staff currently held on JISC Regional Support Centre South West Contact Lists. These include Teaching and Learning Support Staff, Teaching Staff and staff responsible for supporting the provision of Learning Resources in these sectors. The survey will be made available as a Word document to be appended to the explanatory e-mail, and I will utilise the RSCs Survey Monkey instance to make it available via the Internet, so respondents have a choice of format. Survey Monkey is, according to the companies website, an online survey tool that enables people of all experience levels to create their own surveys quickly and easily. Whilst free variants are available, the JISC Regional Support Centre South West have purchased a premium service, with enhanced functionality facilitating a deeper level of data analysis. Survey Monkey is probably the most well prevalent tool in the education sector, and it is a fairly powerful tool which enables users to conduct online surveys and manipulate the data via an intuitive interface, which also generates an attractive and user friendly form for invitees to complete. The data collected is held on the Survey Monkey Server, negating a requirement for local storage, further ameliorating data storage issues for the licence holder. Yun and Trumbo (2000) have posited the following benefits of online assessment tools: Lower cost relative to other data collection methods A supportive environment for actual development of an instrument An online data collection product that for some populations may facilitate a better response rates

29

Support for the data collection process; responses are automatically stored in the providers database with the ability for you to download the results when you wish. This eliminates the need for manual data entry (Marra and Bogue 2006).

Criticisms of Survey Monkey include the fact that whilst the interface is easy to use, as a consequence it doesnt incorporate the potential for high degrees of customisation on the part of the user. In line with recommendations from Marra and Bogue (as above), the system was extensively test driven prior to implementation, as it had been selected by the RSC from a variety of other products which had been piloted; It was found to be the most usable interface from the perspective of respondees (in trial exercises), and had sufficient data manipulation capabilities from our perspective.

Obviously the Regional Support Centre is known to the prospective respondees, as the unit has been in operation within the region since the year 2000, and I have had personal involvement with many of the individuals canvassed via our roster of Institutional Visits, Events and Fora. The RSC South West is one of 13 centres constituting a national network across the UK. Their raison dtre is to promote and facilitate the development of Technology Enhanced Learning across their target communities: Further Education, Higher Education in Further Education, Smaller HE Institutions, Adult Community Learning, Work Based Learning, Offender Learning and Specialist institutions.

Respondents had the option of responding anonymously to the survey, or they could provide varying degrees of personal data-This was a subjective

30

judgement. Obviously prior to conducing the survey I had to clarify and articulate the prospective respondees rights to privacy etc, and therefore defined an Ethics protocol to accompany the survey request, cognate with requirements mandated by the University of Plymouth. Whilst this is only a very small scale piece of research in both magnitude and scope, there are still ethical principles to be incorporated commensurate with the guidelines published in March 1995(3). In essence, these guidelines stipulate that researchers need to adhere to good practice in 6 areas. You can see the limited ethical declaration I drafted as Appendix 1 to this document. Appendix 2 of this document is a print out of the survey results as raw date; Appendix 3 displays the relevant aspects of this as pie-charts.

Firstly, potential respondees should tacitly or explicitly give their informed consent to participate in the study, with especial reference to any factors ..that might reasonably be expected to influence their willingness to take part. In the case of this research, it is highly unlikely that anyone will have their professional identity compromised through confessing a predilection for or aversion to using Interactive Whiteboards, but some of the questions implying free text responses could generate negative feedback about a respondents Institutional training provision etc (although the option of completing anonymously potentially mitigates this entirely). Also, as I am the sole protagonist in the collection and analysis of this data, I can guarantee confidentiality in the scrutiny of the results.

The second covenant is to be ..Open and honest about the research, its purpose and application. This is presumably implicit in any manner of research undertaken, and actually pertains to the prescribed, legitimate and therefore ethical

31

role of deception in certain types of scientific research; A relatively technical disjuncture that is not relevant to this sort of study. The Right to Withdraw is the third consideration; However, the caveats stipulated herein apply to experiments and interviews, and not to Questionnaires, where the sole requirement is that ..the potential respondent should be given the choice not to reply to any particular item or, indeed, the survey as a whole. Protection from harm is another criterion to be considered within the context of the ethics of the study, and whilst the method I am utilising would seem self-evidently safe (i.e. compared to the possible ramifications of ill-administered medical trails for instance), harm in this context can take more abstract forms such as detrimental reputational consequences if confidential responses are disclosed; Researchers therefore ..have to take care not to damage their informants.

The expectation of some manner of debriefing for participants is chronicled next; This essentially entails providing participants with a means of extracting value from the research for their own purposes, which could be mediated via an account of the purpose of the study at the commencement of the investigation, or (more likely in this case), a review of findings on completion. I will make this assignment accessible to respondees once it has been assessed, and make that clear in the accompanying ethical declaration. I have also prcised the aims of the study in this documentation, so potential respondees have some sense of what is trying to be achieved and how the data will accordingly be manipulated. The guidelines suggest that ..If you

promise feedback you have something positive to offer those you intend to research in terms of findings that may influence future policy and practice; However, this does

32

not necessitate total disclosure, rather that the compiler ..use summaries and give the opportunity for feedback rather than giving it regardless of need.

Finally, the Universities ethical requirements compel researchers to ensure confidentiality of participants throughout the conduct and reporting of the research. Whilst this is a thread that runs through other covenants stipulated by the University, this particular proviso pertains to considerations of privacy in more complex circumstances, i.e. where interviews are conducted and transcribed by an intermediary (e.g. a Secretary), hence the need for reports to be coded to ensure anonymity. However, it does make specific reference to circumstances where data are held on Computer, and how the Data Protection Act is applicable. Given that the survey was conducted via a web based technology (and that the information extracted is therefore held remotely on Survey Monkeys servers), I felt it prudent to make reference to the DPA in the ethical statement issued to colleagues with the questionnaire link. This means that should recipients wish to avail themselves of further information, they have been presented with the opportunity to do so.

I opted to use a Questionnaire to capture data, for reasons I will outline. Surprisingly, according to Wikipedia, the modern Questionnaire was devised by the Victorian polymath Sir Francis Galton, who applied statistical methods to the study of human differences and used Questionnaires and Surveys for collecting data on human communities(4). The Questionnaire I have constructed is designed to elicit Closed data (i.e. that pertaining to Quantitative analysis) as well as Open responses (i.e. Free text submissions which lend themselves to a more Qualitative analysis). There are initially a number of questions which are solely there for

33

participants to provide personal information about their name, role and Institutional location, but I have emphasised that continuation through the survey does not require disclosure here. I have specifically included extra tags on the web survey to stress this point on all aspects but the contributors job role/title; I can extract much more value from responses if I have this information, as it will help me orientate the analysis in terms of a breakdown of the perceived usage/efficacy of IWBs and associated technologies within different areas of Institutional provision and across diverse staff roles. Therefore whilst respondees are clearly not obliged to provide this information, I want to make it less obvious in context that they can ignore this question! You could extrapolate that this very mild subterfuge was successful, in as much as only 2 participants skipped this question (Job Title/Role) as opposed to 4 opting not to provide an Institution name, or 5 not furnishing personal name details (admittedly this could very well be too much of an inference to bear scientific examination!).

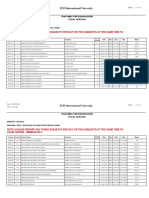

In total, 23 people responded to the survey. Aggregating numbers from across the mail lists that the request was initially sent to, as the original mail was despatched across the national RSC network, I would anticipate that in excess of 300 individuals were approached for participation. I can absolutely assert that within the footprint of the South West Regional Support Centre, 112 individuals were contacted via the JISC Mail lists serving the local HE and HE in FE Community. This means that within this catchment 25.76% of those contacted responded. This constitutes a pretty reasonable response rate, and is almost precisely consistent with date yielded in a survey conducted within the Journal of Computer-Medicated Communication in the US which found the median response rate to online surveys to

34

be 26%! (Kalman, Y et al 2002). It is impossible for me to extrapolate this kind of data for the national mail out, as I contacted staff in analogous roles across the RSC national network (13 centres) asking them to forward the survey request to salient mailing lists as a favour; Consequently, I am unable to ascertain how many lists the message was issued to, the number of individuals approached etc. However, given that the 23 responses have all come from within the coverage of the RSC South West, it seems reasonable to assume that my colleagues were either not especially conscientious in forwarding it, or the survey had such little traction when it was presented as an abstract concept (i.e. without association with my name) that no one from outside the South West catchment felt suitably enthusiastic about participating! Given this eventuality, I will assume that the survey achieved the 25.76% response rate referenced above in relation to a verifiable local distribution.

A analysis of the Job Title/Role data received will be useful in ascertaining perceptions of use and efficacy of IWBs and associated technologies across different roles. Appendix 2 constitutes the full list of 21 responses, but to

encapsulate the broad trends, 11 of these were from Management staff (i.e. those who had titled themselves with suffixes implying seniority and leadership e.g. Managers, Co-ordinators, Heads). 6 of these 11 had a Curriculum (Teaching and Learning focus) e.g. Teaching and Learning Coordinator. 3 had broader remits

implying transcendent, SMT level responsibilities (e.g. Head of Staff and Quality Services), and one managerial respondee was explicitly technical (Technology Coordinator). The last of these 11 is Head of Learning Centres, and if this

appellation is consistent with its usual application, this implies principally responsibility for Learning Resources. If this response rate is representative of the

35

level of engagement and interest in these developments amongst relatively senior staff within Institutions, it is to be celebrated; JISC have previously suggested that organisation like the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education are ideally placed to catalyse and steer strategic developments via senior management development programmes etc, so this quotient is encouraging. In my previous exposition of

Change Agency models, I have already highlighted the peremptory role Caldwell (and others) believe Senior Managers need to occupy to affect change, particularly in the leadership model where managers are the primary motivators who

...envision, initiate or sponsor strategic change of a far reaching or transformational nature. This response rate may suggest that there is an appetite amongst SMT to be engaged over these issues.

Of the remaining 10 respondees whose titles dont imply Management level responsibilities, 2 identify themselves formally as Learning Technologists. There are also Library Staff and Administrators. 3 Academic staff have also identified themselves (one a Lecturer in Biological Sciences, One a Lecturer in ICT and the other styling themselves a Principal Lecturer but not specifying a subject!). This has implications for the survey, as of the 21 respondees who furnished me with Job Title/Role information, 52% appear to occupy positions of Managerial responsibility. 27% of this subset appear to occupy Senior Management posts within their organisations. Also on this reckoning, 14% are also occupied in Academic posts, and interestingly only 2 Learning Technologists have responded. Of the entire

response pool, only 3 individuals (including these LTs) have identified themselves as occupying specifically technical roles (14%). Consequently it could be asserted that respondees come from predominantly a pedagogical/managerial incumbency

36

rather than a technical one. Whether or not this means that the survey will isolate strategic rather than operational trends in the deployment of IWBs and Associated Technologies will hopefully be discernable from an analysis of the results. As discussed in section one, BECTA have previously made inferences from data evidencing a need for more Learning Technologists to imbue pedagogy within users, as well as purely to facilitate technical operation; They found too few were in post to effectively support staff in the use of hardware in their teaching, and to help them develop the requisite confidence, competence and resource to comfortably use new bits of kit with learners who they may very well (mis)perceive as having better skills in this regard than they do. This low response rate from Learning Technologists may mean simply that they either didnt receive the survey or were not inclined to respond, but there is also a possibility that it suggests BECTAs assertion for FE is also true within the broader post-compulsory milieu, and that there simply arent enough of them.

Analysing where results came from (Question 5: Which type of Institution do you work in?), 11 of the 23 respondees come from an HE background (47.8%). This cohort can be disaggregated further, with 2 (8.7%) respondees coming from within Universities, 3 (13%) coming from within other HE Institutions and 6 (26.1%) from within HE in FE environments. In this context, I am defining HE Institutions cognate with criteria developed by the Higher Education Statistics Agency who define them as <quote>. Of the remaining 58.2% of respondees, 7 (30.4%) came from Further Education (making this area the single largest contingent), 2 (8.7%) came from Specialist Colleges and 5 (21.7%) identify themselves as Others. Representing over a fifth of respondees, this represents a significant grouping, and in retrospect I

37

believe constitutes an error in data collection in my part. This is because I gave no option for these individuals to expand on this definition and provide me with more accurate information on their affiliations. Given the constituencies covered by the Regional Support Centres, its reasonable to assume that these respondees come from Adult and Community Learning or Work Based Learning backgrounds, as these are the two major areas of support not covered by the specific categories listed in the questionnaire. However, it would have been useful to have extrapolated some

further information on the sectoral dispersion of respondees, and it would have been prudent for me to have at least split down the other category into ACL and WBL classifications. My educated hunch is that the Other contingent would then have been eliminated (as the Questionnaire was not distributed outside of the roster detailed above). This means that significantly, the majority of respondees may have come from outside the HE sector (extrapolating that the 21.7% Other element where from ACL/WBL), with 14 out of 23 respondents (60.86%), whilst of the 39.14% of respondees from an HE environment, the majority (54.5% of this subset) worked within an HE in FE milieu.

Moving beyond capturing demographic data, the next section of the Questionnaire focused on capturing quantitative data relating to the volume and usage of IWBs within the contexts described previously. In response to the question As far as you are aware, does your Institution currently have any Interactive Whiteboards?, 100% of the 19 respondees said that they were. Interestingly, 4 respondees skipped this question, and its difficult to know why given that responses were anonymous and disclosure of a lack of awareness was therefore not an issue. Consequently we cannot infer either that these 4 respondees were articulating a lack

38

of awareness which they did not want to communicate, or that in these 4 cases the Institution had no IWBs. It may be that disambiguation could have been achieved had the preface As far as you are aware been removed from the question, as this would have implied a definitive answer was required (or at least a Dont Know option could have been appended); However, the study is also mapping staff perceptions of the availability and efficacy of these units, so from this perspective their could be an implication to the fact that 4 out of 23 (17.39%) of potential respondees refrained from answering the question. It could be deduced that these respondees were not aware of the IWB allocation within their environment and did not want to expose their relative ignorance, or conversely that they were actually signalling the equivalent of a No answer in not replying. This is impossible to discern from this data.

There were 18 responses to the question How many Interactive Whiteboards does your Institution currently possess?; 38.9% of respondees believe that over 50 IWBs reside within their organisation, a significant minority. In descending order, 27.8% have 0-10, 22.2% have between 21-and 30 and 11.1% have between 41-50. However, the value of this information is negligible as obviously numbers are relative to the size of the establishment (I.e. a small enough establishment could have total classroom coverage with 10 boards). However, with the exception of the Work

Based Learning provider who responded to the survey, I am personally aware that all of the respondees work within Institutions with student numbers in the thousands, so it is fair to assume that significant penetration would be indicated by a 50 plus reckoning. In retrospect it would also have been prudent to include a free-text

39

submission after this question for respondents to advise on exactly how many units they believed were currently in situ.

I then endeavoured to ascertain whether or not these boards were fixed or movable; This is an important distinction as there are manifestly inherent implications for usage predicated on their portability. It can be reasonably inferred that static boards lend themselves to conventional classroom delivery, whilst mobile units have at least the potential to be utilised in less formally didactic environs e.g. in a simulated vocational environment such as kitchens, salons etc. extrapolations are highly speculative. Again, such

In the survey, out of 19 respondents 12

(70.6%) reported that their boards were fixed, and 7 (29.4%) reported that they had access to both. It appears from this evidence therefore that no Institutions have an entire range of exclusively portable boards.

The next question is a free text submission, attempting to educe more details concerning the location of the boards. Within the question, I gave some examples of potential venues, which may have influenced the responses, given that all but 4 of the 17 responses cited these examples (Class Room, Lecture Theatre, Training Room). In retrospect, it might have been sensible not to have offered these

exemplar categories as they are insufficiently germane to the specific environment within which the technology is housed. For example, Class Room is too generic, and does not give a designation to the specific milieu wherein a board resides; Is it a straight-forward conference style environment, assisting Chalk and talk delivery, or is it employed in a vocational classroom environment and/or utilised in a more interactive fashion? Whilst an attempt to elicit this information is made explicitly later

40

on in the study, it might have been advisable to either not have suggested specific locales within the question, or to have added an ancillary free-text box to allow respondents to elucidate upon the location e.g. in a mock School classroom environment, in a Simulated Salon environment etc.

Of the 4 respondents who did not respond with one of the suggested answers, One respondent advised that their boards were resident in their Learning Resource Centres, One in both the LRC and within a Studio Environment (implying vocational application), One in a Training Room, and One in an IT lab and Classroom environment. Of the 13 other respondents, 9 advised that their IWBs were solely resident within a Classroom environment; Two had installed them in both Classrooms and Meeting Rooms, One in Classrooms, Lecture Theatres and Meeting Rooms, and One in Classrooms and Lecture Theatres. What is interesting is that only 4 respondees (23.5%) understood that IWBs were present in Lecture Theatres. Given the usual preponderance of presentational media in these environments, it seems surprising that only 23.5% of respondents believe IWBs, with their attendant high degree of interactivity and their inherent value as pure display media, are not more heavily utilised in this context.

It is also striking that out of 23 respondees, 6 chose to skip the question (26%); I could extrapolate from this that over a quarter of respondents dont know where the boards are situated (and consequently infer that they have experienced little or no personal exposure to them). However, this figure is also congruent with the earlier finding that 7 of the respondents believed their Institutions had peripatetic boards, and therefore these boards have no fixed abode. Again with the benefit of

41

hindsight I would rephrase this question; Asking where the fixed boards were permanently located presupposes that itinerant IWBs are not utilised exclusively in a specific location irrespective of their portability, which they very possibly are. I would have gained more useful data if I had either omitted any references to fixed boards in this question, or included a supplementary question enquiring as to the most usual habitats of the roaming IWBs. As it is, I have no data relating to the typical whereabouts of mobile boards, which is a rather glaring omission, with over a quarter of respondents not being asked to account for the utility of this deployment.

The next question, How frequently do you use an Interactive Whiteboard?, received 15 answers, and 8 correspondents skipped the question. This accounts for over a third (35%) of respondents, and is difficult to account for when 19 out of 23 had earlier responded Yes, there Institution currently had Interactive Whiteboards (83%). It implies either that 4 respondents reside in Institutions which have IWBs, but dont use them, or that these 4 respondents did not want to disclose their usage. One of the 6 presented multiple-choice responses is Never, so its reasonable to suppose that if these individuals did not utilise the Boards, this would be the apposite response. I would surmise that this means that there respondents did not want to disclose their usage.

Evaluating the responses, the most regular usage was less than once a week (6, or 40%); I thought any other epoch would be unsuitably vague as most people would not really be aware of whether they used a particularly application beyond a weekly frequency (e.g. Monthly, Quarterly). 3 users (20%) have advised that they use the boards at least once a week, whilst 2 use the boards at least once

42

a day and 2 more in every lesson (i.e. 4 in total utilising them daily, or 27% of respondents). 1 user employs them for tuition in specific subjects, and an additional user apparently never uses the boards. A supplementary question solicits further details concerning use of the boards within specific subject disciplines; Even though only 1 respondent in the survey advised they use them for specialised delivery, there were 2 responses to this enquiry, namely for Software Specialist Lectures and GIS (Geographic Information System) Training. Again, with the benefit of hindsight were I revisiting this survey I would omit the criteria for a response here being contingent on an indication of specialist tuition, and just insert another question asking within which subject domain(s) the IWBs were most commonly used, prompting a free-text response. This would give me an idea of the perceived

efficacy of the units within particular disciplines; Currently the survey extrudes information on geographical context and group deployment, but not on scholarly application.

Moving on, the questionnaire makes enquiries concerning group types. Obviously multiple responses were permitted within Survey Monkey here, as I wanted to capture as much information as possible on all aspects of utilisation. 13 people responded to this question (i.e. it was skipped by 10). Revealingly, the

largest number (8, or 61.5%) utilised the technology with other staff members within their Institution (e.g. in Departmental Meetings/Training Sessions etc). 7

respondents (53.8%) used Boards in Whole class environments (e.g. Lectures), 6 (46.2%) in small groups (e.g. Tutorials and Seminars) and 1 respondent reported using the boards with individuals. Given the earlier indications of prevalence in a classroom milieu, its interesting that the majority of users exploit the technology with

43