Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jan.12 Cases

Загружено:

Jonathan Paolo DimaanoИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jan.12 Cases

Загружено:

Jonathan Paolo DimaanoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

[G.R. No. 130656. June 29, 2000] PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs.

ARMANDO REANZARES* also known as ARMANDO RIANZARES, accused-appellant.* DECISION BELLOSILLO, J.: This case is with us on automatic review of the 26 May 1997 Decision[1] of the Regional Trial Court of Tanauan, Batangas, finding accused ARMANDO REANZARES also known as "Armando Rianzares" guilty of Highway Robbery with Homicide under PD 532[2] and sentencing him to the extreme penalty of death. He was also ordered to pay the heirs of his victim Lilia Tactacan P172,000.00 for funeral, burial and related expenses, P50,000.00 as indemnity for death, P1,000.00 for the cash taken from her bag, and to reimburse Gregorio Tactacan P2,500.00 for the Seiko wristwatch taken from him. The facts, except as to the identity of accused Armando Reanzares, are undisputed. Spouses Gregorio Tactacan and Lilia Tactacan owned a sari-sari store in San Miguel, Sto. Tomas, Batangas. On 10 May 1994 at around 8:10 in the evening, the Tactacan spouses closed their store and left for home in Barangay San Roque, Sto. Tomas, Batangas on board their passenger-type jeepney. As Gregorio was maneuvering his jeep backwards from where it was parked two (2) unidentified men suddenly climbed on board. His wife Lilia immediately asked them where they were going and they answered that they were bound for the town proper. When Lilia informed them that they were not going to pass through the town proper, the two (2) said they would just get off at the nearest intersection. After negotiating some 500 meters, one of the hitchhikers pointed a .38 caliber revolver at Gregorio while the other poked a balisong at Lilia's neck and ordered Gregorio to stop the vehicle. Two (2) other persons, one of whom was later identified as accused Armando Reanzares, were seen waiting for them at a distance. As soon as the vehicle stopped, the accused and his companion approached the vehicle. Gregorio was then pulled from the driver's seat to the back of the vehicle. They gagged and blindfolded him and tied his hands and feet. They also took his Seiko wristwatch worth P2,500.00. The accused then drove the vehicle after being told by one of them, "Sige idrive mo na."[3] Gregorio did not know where they were headed for as he was blindfolded. After several minutes, he felt the vehicle making a u-turn and stopped after ten (10) minutes. During the entire trip, his wife kept uttering, "Maawa kayo sa amin, marami kaming anak, kunin nyo na lahat ng gusto ninyo." Immediately after the last time she uttered these words a commotion ensued and Lilia was heard saying, "aray!" Gregorio heard her but could not do anything. After three (3) minutes the commotion ceased. Then he heard someone tell him, "Huwag kang kikilos diyan, ha," and left. Gregorio then untied his hands and feet, removed his gag and blindfold and jumped out of the vehicle. The culprits were all gone, including his wife. He ran to San Roque East shouting for help.[4] When Gregorio returned to the crime scene, the jeepney was still there. He went to the drivers seat. There he saw his wife lying on the floor of the jeepney with blood splattered all over her body. Her bag containing P1,200.00 was missing. He brought her immediately to the C. P. Reyes Hospital where she was pronounced dead on arrival.[5] At the time of her death Lilia Tactacan was forty-eight (48) years old. According to Gregorio, he was deeply depressed by her death; that he incurred funeral, burial and other related expenses, and that his wife was earning P3,430.00 a month as a teacher.[6] Dr. Lily D. Nunes, Medical Health Officer of Sto. Tomas, Batangas, conducted a post-mortem examination on the body of the victim. Her medical report disclosed that the victim sustained eight (8) stab wounds on the chest and abdominal region of the body. She testified that a sharp pointed object like a

long knife could have caused those wounds which must have been inflicted by more than one (1) person, and that all those wounds except the non-penetrating one caused the immediate death of the victim.[7] Subsequently, two (2) Informations were filed against accused Armando Reanzares and three (3) John Does in relation to the incident. The first was for violation of PD 532 otherwise known as the Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery Law of 1974 for allegedly conspiring, with intent to gain and armed with bladed weapons and a .38 caliber revolver, to rob and carry away one (1) Seiko wristwatch owned by Gregorio Tactacan and P1,000.00 cash of Lilia Tactacan, and on the occasion thereof, killed her. The second was for violation of RA 6539, An Act Preventing and Penalizing Carnapping, for taking away by means of violence and intimidation of persons one (1) passenger-type jeepney with Plate No. DBP 235 owned and driven by Gregorio Tactacan and valued at P110,000.00. Only the accused Armando Reanzares was arrested. The other three (3) have remained unidentified and at large. The accused testified in his defense and claimed that he could not have perpetrated the crimes imputed to him with three (3) others as he was in Barangay Tagnipa, Garchitorena, Camarines Sur, for the baptism of his daughter Jessica when the incident happened.[8] His father, Jose Reanzares, corroborated his story. Jose claimed that the accused borrowed P500.00 from him for the latter's trip to Bicol although he could not say that he actually saw the accused leave for his intended destination.[9] To bolster the alibi of the accused, his brother Romeo Reanzares also took the witness stand and alleged that he saw the accused off on 9 May 1994, the day before the incident. Romeo maintained that he accompanied the accused to the bus stop that day and even helped the latter carry his things to the bus. He however could not categorically state where and when the accused alighted or that he in fact reached Bicol.[10] On 26 May 1997 the trial court found the prosecutions evidence credible and ruled that the alibi of the accused could not prevail over his positive identification by complaining witness Gregorio Tactacan. The court a quo declared him guilty of Highway Robbery with Homicide under PD 532 and sentenced him to death. It further ordered him to pay the heirs of Lilia Tactacan P50,000.00 as indemnity for death, P172,000.00 for funeral, burial and related expenses, and P1,000.00 for the cash taken from her bag. The accused was also ordered to reimburse Gregorio Tactacan P2,500.00 for the Seiko wristwatch taken from him.[11] But the trial court exonerated the accused from the charge of carnapping under RA 6539 for insufficiency of evidence. The accused insists before us that his conviction for Highway Robbery with Homicide under PD 532 is erroneous as his guilt was not proved beyond reasonable doubt. He claims that the testimony of private complainant Gregorio Tactacan, who implicated him as one of the perpetrators of the crime, is incredible. He maintains that Gregorio failed to identify him because when the latter was questioned he stated that he did not know any of the culprits. He also claims that in the publication of Hotline by Tony Calvento in People's Tonight, Gregorio even asked the readers to help him identify the malefactors. The trial court observed that Gregorio Tactacan testified in a categorical, straightforward, spontaneous and frank manner, and was consistent on cross-examination. Indeed, Gregorio might not have immediately revealed the name of accused Armando Reanzares to the police authorities when he was first investigated but the delay was not an indication of a fabricated charge and should not undermine his credibility considering that he satisfactorily explained his reasons therefor. According to him, he did not immediately tell the police about the accused because he feared for the safety of his family as his neighbors told him that they saw some people lurking around his house on the day of the incident. Moreover, he was advised not to mention any names until after the burial of his wife. No ill motive could be attributed to him for implicating the accused. If at all, the fact that his wife died by reason of the incident even lends credence to his testimony since his natural interest in securing the conviction of the guilty would deter him from implicating persons other than the real culprits, otherwise, those responsible for the perpetration of the crime would escape prosecution. To further undermine the credibility of Gregorio, the accused underscores Gregorio's refusal to be subjected to a lie detector test. We cannot subscribe to this contention as the procedure of ascertaining the

truth by means of a lie detector test has never been accepted in our jurisdiction; thus, any findings based thereon cannot be considered conclusive. Finally, the accused chides Gregorio for supposedly suppressing a very material piece of evidence, i.e., the latter failed to present as witnesses a certain Renato and his wife who allegedly saw the holduppers running away from the crime scene. But this is only a disputable presumption under Sec. 3, par. (e), Rule 131, of the Rules of Court on evidence, which does not apply in the present case as the evidence allegedly omitted is equally accessible and available to the defense. These attempts of the accused to discredit Gregorio obviously cannot hold ground. Neither can they bolster his alibi. For alibi to be believed it must be shown that (a) the accused was in another place at the time of the commission of the offense, and (b) it was physically impossible for him to be at the crime scene.[12] In this case, the accused claims to have left for Bicol the day before the incident. To prove this, he presented his father and brother but their testimonies did not meet the requisite quantum to establish his alibi. While his father testified that the accused borrowed money from him for his fare to Bicol for the baptism of a daughter, he could not say whether the accused actually went to Bicol. As regards the claim of Romeo, brother of the accused, that he accompanied the accused to the bus stop on 9 May 1994 and even helped him with his things, seeing the accused off is not the same as seeing him actually get off at his destination. Given the circumstances of this case, it is possible for the accused to have alighted from the bus before reaching Bicol, perpetrated the crime in the evening of 10 May 2000, proceeded to Bicol and arrived there on 12 May 2000 for his daughters baptism. Thus the trial court was correct in disregarding the alibi of the accused not only because he was positively identified by Gregorio Tactacan but also because it was not shown that it was physically impossible for him to be at the crime scene on the date and time of the incident. Indeed the accused is guilty. But that the accused was guilty of Highway Robbery with Homicide under PD 532 was erroneous. As held in a number of cases, conviction for highway robbery requires proof that several accused were organized for the purpose of committing it indiscriminately.[13] There is no proof in the instant case that the accused and his cohorts organized themselves to commit highway robbery. Neither is there proof that they attempted to commit similar robberies to show the "indiscriminate" perpetration thereof. On the other hand, what the prosecution established was only a single act of robbery against the particular persons of the Tactacan spouses. Clearly, this single act of depredation is not what is contemplated under PD 532 as its objective is to deter and punish lawless elements who commit acts of depredation upon persons and properties of innocent and defenseless inhabitants who travel from one place to another thereby disturbing the peace and tranquility of the nation and stunting the economic and social progress of the people. Consequently, the accused should be held liable for the special complex crime of robbery with homicide under Art. 294 of the Revised Penal Code as amended by RA 7659[14] as the allegations in the Information are enough to convict him therefor. In the interpretation of an information, what controls is the description of the offense charged and not merely its designation.[15] Article 294, par. (1), of the Revised Penal Code as amended punishes the crime of robbery with homicide by reclusion perpetua to death. Applying Art. 63, second par., subpar. 2, of the Revised Penal Code which provides that "[i]n all cases in which the law prescribes a penalty composed of two indivisible penalties, the following rules shall be observed in the application thereof: x x x 2. [w]hen there are neither mitigating nor aggravating circumstances in the commission of the deed, the lesser penalty shall be applied," the lesser penalty of reclusion perpetua is imposed in the absence of any modifying circumstance.

As to the damages awarded by the trial court to the heirs of the victim, we sustain the award of P50,000.00 as civil indemnity for the wrongful death of Lilia Tactacan. In addition, the amount of P50,000.00 as moral damages is ordered. Also, damages for loss of earning capacity of Lilia Tactacan must be granted to her heirs. The testimony of Gregorio Tactacan, the victims husband, on the earning capacity of his wife, together with a copy of his wifes payroll, is enough to establish the basis for the award. The formula for determining the life expectancy of Lilia Tactacan, applying the American Expectancy Table of Mortality, is as follows: 2/3 multiplied by (80 minus the age of the deceased).[16] Since Lilia was 48 years of age at the time of her death,[17] then her life expectancy was 21.33 years. At the time of her death, Lilia was earning P3,430.00 a month as a teacher at the San Roque Elementary School so that her annual income was P41,160.00. From this amount, 50% should be deducted as reasonable and necessary living expenses to arrive at her net earnings. Thus, her net earning capacity was P438,971.40 computed as follows: Net earning capacity equals life expectancy times gross annual income less reasonable and necessary living expenses Net earning capacity (x) x = = = 2 (80-48) ...... 3 21.33 P438,971.40 x x [P41,160.00 P20,580.00 = Life expectancy x Gross annual income -

reasonab living ex

P20,580.

However, the award of P1,000.00 representing the cash taken from Lilia Tactacan must be increased to P1,200.00 as this was the amount established by the prosecution without objection from the defense. The award of P172,000.00 for funeral, burial and related expenses must be reduced to P22,000.00 as this was the only amount sufficiently substantiated.[18] There was no other competent evidence presented to support the original award. The amount of P2,500.00 as reimbursement for the Seiko wristwatch taken from Gregorio Tactacan must be deleted in the absence of receipts or any other competent evidence aside from the self-serving valuation made by the prosecution. An ordinary witness cannot establish the value of jewelry and the trial court can only take judicial notice of the value of goods which is a matter of public knowledge or is capable of unquestionable demonstration. The value of jewelry therefore does not fall under either category of which the court can take judicial notice.[19] WHEREFORE , the Decision appealed from is MODIFIED. Accused ARMANDO REANZARES also known as "Armando Rianzares" is found GUILTY beyond reasonable doubt of Robbery with Homicide under Art. 294 of the Revised Penal Code as amended and is sentenced to reclusion perpetua. He is ordered to pay the heirs of the victim P50,000.00 as indemnity for death, another P50,000.00 for moral damages, P1,200.00 for actual damages, P438,971.40 for loss of earning capacity, and P22,000.00 for funeral, burial and related expenses. Costs de oficio. SO ORDERED.

[G.R. No. 131829. June 23, 2000] PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. RONNIE AGOMO-O, accused, EDDY PANEZA and OSCAR SERVANDO, accused-appellants. DECISION MENDOZA, J.: This is an appeal from a decision [1] of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 23, Iloilo City, finding accusedappellants Eddy Paneza and Oscar Servando, together with accused Ronnie Agomo-o, [2] guilty of highway robbery under P.D. No. 532, and sentencing them to suffer the penalty of reclusion perpetua and to indemnify the heirs of the victim, Rodito Lasap, in the amount of P50,000.00. The information [3] against accused-appellants and their co-accused Ronnie Agomo-o charged That on or about the 22nd day of September, 1993, along the national highway, in the Municipality of San Enrique, Province of Iloilo, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the abovenamed accused, conspiring confederating and mutually helping one another, armed with a pistolized homemade shotgun and bladed weapons announced a hold-up when the passenger jeepney driven by Rodito Lasap reached Barangay Mapili, San Enrique, Iloilo, and by means of violence against or intimidation, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously, with intent to gain, take steal and carry away cash money, in the amount of FIFTY PESOS (P50.00), Philippine Currency and a wrist watch with a value of THREE THOUSAND PESOS (P3,000.00) both belonging to JOSE AMADOR, another amount of ONE HUNDRED THIRTY PESOS (P130.00) belonging to FREDDIE AGRABIO, and the amount of TWO HUNDRED PESOS (P200.00) belonging to the driver, RODITO LASAP, with a total value of THREE THOUSAND THREE HUNDRED EIGHTY PESOS (P3,380.00), Philippine Currency, to the damage and prejudice of the aforesaid persons and on the occasion of said robbery, the accused, with intent to kill shot the driver RODITO LASAP, with the firearms they were provided at that time which resulted [in] the death of Rodito Lasap and with deliberate intent to kill likewise stab one FREDDIE AGRABIO with a bladed weapon they were provided thus hitting him on the left elbow, thus commencing the commission of homicide directly by overt acts but did not perform all the acts of execution which would produce the felony by reason of some cause or accident other than their own spontaneous desistance. The prosecution evidence showed that, on September 22, 1993, at around 7:30 in the evening, a passenger jeepney driven by Rodito Lasap en route to Passi, after coming from Sitio Gomez, Barangay Abaca, San Enrique, Iloilo, was stopped by three men, among them was the accused in this case, Ronnie Agomo-o, who, armed with a gun, announced a hold-up and ordered the driver to turn off the engine. After Lasap obeyed, Ronnie Agomo-o shot him just the same.[4] That same night, Rodito Lasap died as a result of multiple gunshot wounds.[5] A passenger, Freddie Agrabio, who was seated beside the driver, transferred, out of fright, to the rear portion of the jeep. He was then told to lie face down on the floor of the vehicle. Afterwards, he was asked to hand in his wallet containing P130.00 to one of the robbers. The accused then ordered the passengers to alight from the jeepney and keep their hands up. As they were doing so, accused-appellant Paneza stabbed Agrabio, hitting him on the left elbow. Agrabio ran from the scene.[6] Another passenger of the jeepney was Jose Amador. He saw the three accused coming from the sugarcane field at Barangay Mapili. The three stopped the passenger jeepney. Eddy Paneza took Amadors wallet containing P50.00 as well as his wrist watch, all the while pointing a pinote at him. He thought it was Oscar Servando who stabbed Freddie Agrabio. When Agrabio ran, Amador also ran.[7] Amador said that he was seated behind the driver and was thus able to see the accused as the moon was bright and there was light coming from the jeepney.[8]

SPO1 Joely Lasap and his companions received a report of the hold-up. Some of them went to Barangay Mapili to respond to the report of the incident. At around four oclock in the morning of the following day, SPO1 Lasap and his companions found three empty shells of a 12-gauge shotgun.[9] SPO1 Lasap is a first cousin of the victim Rodito Lasap.[10] Dr. Jason Palomado of the Passi District Hospital treated Freddie Agrabio for a wound on his left elbow. The wound was two centimeters in length and two centimeters in depth. Agrabio was discharged from the hospital the following morning.[11] Dr. Palomado issued a medical certificate[12] stating that Agrabio needed treatment for a period of 9 to 30 days. On September 28, 1993, Jocelyn Agomo-o went to the San Enrique Police Station and turned over a wrist watch allegedly taken during the hold-up. The watch was eventually returned to its owner, Jose Amador. [13] The defense of the accused was alibi. Ronnie Agomo-o claimed that he was at the Provincial Hospital with his mother from September 21 to September 23, 1993 to watch over his sick brother.[14] Accusedappellant Eddy Paneza said he was in his aunts house in Rizal, Palapala, Iloilo in the morning of September 22, 1993 and that, at around 10 oclock, he accompanied his aunt, Teresa Escultero, to Brgy. Madarag, San Enrique, arriving there at three oclock in the afternoon. They went there to talk with the family of the prospective husband of his aunts daughter. Eddy Paneza slept in the grooms house and proceeded to Barangay Bawatan the following morning.[15] Teresa Escultero corroborated Eddy Panezas testimony.[16] Lastly, Ma. Elena Servando, sister-in-law of Oscar Servando, testified that on September 22, 1993, accused-appellant Oscar Servando accompanied her to Sitio Baclayan, San Enrique to gather corn. They went back home at around six oclock in the evening. They removed the corn ears from the cob and finished doing so at 11 oclock that evening. The following morning, they dried the corn until the afternoon.[17] The lower court then rendered a decision on February 5, 1997 finding the accused guilty. The dispositive portion of its decision states: WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered finding accused Ronnie Agomo-o, Eddy Paneza and Oscar Servando GUILTY beyond reasonable doubt of violating the provisions of Section 3, Paragraph (b) of Presidential Decree No. 532, otherwise known as the Anti-Piracy and AntiHighway Robbery Law of 1974, particularly the last portion thereof, and sentences them to suffer a penalty of imprisonment of Reclusion Perpetua, and to pay the heirs of Rodito Lasap civil indemnity in the amount of P50,000.00. The accused Ronnie Agomo-o, Eddy Paneza and Oscar Servando who are presently detained are entitled to be credited in full with the entire period of their preventive detention. SO ORDERED.[18] It is from this judgment that Paneza and Servando appealed. Ronnie Agomo-o did not appeal. Accusedappellants contend: I. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN FINDING ALL THE ACCUSED RONNIE AGOMO-O, EDDY PANEZA and OSCAR SERVANDO GUILTY BEYOND REASONABLE DOUBT OF VIOLATING THE PROVISIONS OF SECTION 3, PARAGRAPH (b) OF PRESIDENTIAL DECREE NO. 532, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE ANTI-PIRACY AND ANTI-ROBBERY LAW OF 1974, IN SPITE OF THE FACT THAT THERE WAS NO PROOF OF CONSPIRACY. II. THE TRIAL COURT FURTHER ERRED IN IMPOSING A PENALTY OF IMPRISONMENT OF RECLUSION PERPETUA TO ALL THE ACCUSED AND TO PAY THE HEIRS OF RODITO LASAP CIVIL INDEMNITY IN THE AMOUNT OF P50,000.00.

III. THE TRIAL COURT ERRED IN NOT ACQUITTING ACCUSED-APPELLANT OSCAR SERVANDO IN SPITE OF THE ABSENCE OF PROOF AS TO HIS PARTICIPATION. We find the appeal to be without merit. First . Accused-appellants claim that the testimony of Freddie Agrabio was incredible and highly improbable. They contend that Agrabio could not have been beside the driver when the latter was shot; otherwise, he, too, would have been injured considering his proximity to the driver.[19] That Freddie Agrabio could also have been hit is sheer speculation and conjecture and, therefore, not a valid argument against the veracity of his testimony. Freddie Agrabio could not have been hit because Rodito Lasap was shot at close range.[20] The latter was shot on the chest,[21] hence, the scattered pellets only hit that area. Moreover, Freddie Agrabio was the only one seated in front of the jeepney beside the driver.[22] Under such circumstances, the passenger could have moved away from the driver. He may have been seated next to the driver but not close enough to be within the range of the shotgun. The trial court correctly relied on the positive identification of the accused made by Freddie Agrabio and Jose Amador. No reason has been advanced why the testimonies of these witnesses should not be believed. Hence, the trial courts evaluation of the witnesses testimonies must be accorded great respect since it had the opportunity to observe and examine the witnesses conduct and demeanor on the witness stand.[23] On direct examination, Freddie Agrabio testified as follows: Q. Mr. Freddie Agrabio, on September 22, 1993, around 7:30 in the evening, more or less, could you remember where were you? A. Yes, sir. Q. Where were you? A. I was sitting in the front seat of the jeepney. Q. Why were you there? A. I was going to town. Q. Of what town? A. Passi. Q. Where did you come from? A. From Sitio Gomez. Q. What municipality? A. Sitio Gomez, Brgy. Abaca, San Enrique, Iloilo. Q. While riding on the said jeepney, could you remember if any incident that happened? A. When we arrived at the crossing Ronie Agomo-o appeared bringing with him a firearm. Q. Could you remember what crossing was that? A. Crossing [Barangay] Mapili. Q. Of what municipality is Brgy. Mapili? A. San Enrique. Q. Was Ronie Agomo-o alone? A. There were three of them. Q. Could you remember who were his other companions? A. Eddy Paneza and Servando. Q. By the way, do you know the full [name] of this certain Servando? A. I just knew him as Servando. Q. Why do you know this Ronie Agomo-o? A. Because he often drive a jeep and we often pass that place. Q. If Ronie Agomo-o is inside the courtroom, could you point out where is he? A. Yes, sir. Q. Point to him? A. He is there. (witness pointing to man seated on the accused bench who when asked [identified himself] as Ronie Agomo-o.) Q. How about this Eddy Paneza, could you point out where is he in this Court?

A. Yes, sir, he is also there. (witness pointing to another seated on the accused bench who when asked identified himself as Eddy Paneza) Q. How about a certain Servando you mentioned? A. He is there. (witness again pointing to another man situated on the accused bench and when asked his name identified himself as Oscar Servando) Q. After you saw this Ronie Agomo-o appeared with a shotgun and declared hold-up, what happened further? A. He instructed the driver Rodito Lasap to turn off the engine of the jeep and upon instructing Rodito he shot Rodito Lasap. Q. Was Rodito Lasap hit by Ronie Agomo-o? A. Yes, sir. Q. And what happened further? A. Then I transferred to the back portion of the jeep at the passengers area. Q. After you transferred at the back portion of the passenger jeep, what did the three (3) outlaws do, if any? A. They told us to give our money to them and not to do anything bad. COURT Q. Who ordered the passengers to turn over their money? A. The three (3) of them, Your Honor. .... Q. After the three (3) accused in this case ordered you and your companions to give your money, did you follow their order? A. Yes, sir, I gave to them my wallet. Q. Was your wallet empty at the time you gave them to the holdupper? A. There was. The money inside was P130.00. COURT Q. To whom did you give your wallet? A. I really dont know to whom I gave because I was facing down when I gave my wallet. Q. Why did you lie down? A. They told me. Q. What did they tell you? A. They told me not to do anything bad. COURT Proceed. PROSECUTOR Q. After you gave your wallet to the holdupper, what happened further, if any? A. They instructed us to alight from the jeep and kept our hands up. Q. And what happened further? A. And then Eddy Paneza stabbed me. Q. Were you hit? A. Yes, sir. COURT Q. Where? A. Here, Your Honor. (witness pointing his left elbow) Q. How many times did Eddy Paneza stab you? A. Once. After he stabbed me I ran away. Q. Were you injured? A. Yes, Your Honor. (witness showing to the Bench his left elbow with a scar) .... COURT Proceed. PROSECUTOR Q. You said that Eddy Paneza, one of the accused in this case stabbed you. Were you able to have your wound treated? A. Yes, sir. .... COURT Q. In what hospital were you treated?

A. At Passi. .... PROSECUTOR Q. After Eddy Paneza stabbed you, what happened? A. We scampered away and when I turned my back I saw Jose Amador following me. Q. Was Jose Amador one of the passengers in the said jeepney? A. Yes, sir.[24] Freddie Agrabio was steadfast in his testimony despite rigorous cross-examination by defense counsel. He further testified: CROSS EXAMINATION BY ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. You said you were sitting on the front seat when this Ronie Agomo-o appeared from the sugarcane plantation, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. Q. And immediately after Ronie Agomo-o appeared from the sugarcane plantation, he shouted hold-up, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. Q. And you were still on the front seat of the passenger jeep at the time when he announced there was hold-up, is that correct? A. I was beside the driver, at the right. Q. You mean to tell this Honorable Court that immediately he shouted hold-up, he shot the driver, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. Q. And at the time you were near the driver? A. Yes, sir. Q. You said that Ronie [Agomo-o] used a pistolized homemade shotgun, is that correct? A. I cannot identify what kind of firearm because it was dark. Q. Are you sure of that, Mr. Witness? A. Yes, sir. .... WITNESS A. I am sure that the firearm is a pistolized homemade shotgun. ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. When Ronie Agomo-o shot the driver Rodito Lasap, how far were you then sitting on the front seat with the Rodito Lasap? A. We were side by side. Q. And you saw at the time Ronie Agomo-o shot Rodito Lasap, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. Q. Where was Ronie Agomo-o at the time when he shot Rodito Lasap? A. He was at the left side of the driver. COURT Q. How far was Ronie Agomo-o from Rodito Lasap when he shot the latter? A. About one arms length. Q. You saw the accused pointed that shotgun to Rodito Lasap? A. Yes, Your Honor. Q. When you saw Ronie Agomo-o pointed that firearm to the driver, Rodito Lasap, could you tell this Court what was the distance of the tip of the barrel of the shotgun to the body of Rodito Lasap? A. The tip of the barrel is about six (6) to seven (7) inches. COURT From the body of Rodito Lasap. Proceed. ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. In what particular part of the body of Rodito Lasap did Ronie Agomo-o pointed the shotgun? A. Middle of his breast. Q. And you were situated beside Rodito Lasap, is that correct? [Q]. You did not hide when Ronie Agomo-o pointed the shotgun to Rodito Lasap? A. I was not able to move. Q. You mean to tell this Honorable Court when the firearm was fired, you were still beside Rodito Lasap, is that correct?

A. When the firearm was fire[d] I was still beside Rodito Lasap. Q. And despite the burst of the shotgun you were not injured by that particular burst? A. I was not hit. Q. The only injury which you suffered at the time was the stab wound which Eddy Paneza inflicted upon your person, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. COURT Q. What happened to Rodito Lasap when he was shot by Ronie Agomo-o? A. He laid down in the front seat. COURT Proceed. ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. How about you after the shot, what did you do? A. I transferred to the back portion of the jeep. Q. You mean to tell this Honorable Court you went down from the front seat then you transferred to the back portion of the jeep? A. No, sir, I just climbed at the back. Q. At the time of the incident, how many persons were sitting at the front seat excluding the driver? A. There were three (3) of us. Q. Who were your companions, could you remember? A. Joey and Junior. Q. And this Joey and Junior were still sitting at the front seat when Ronie Agomo-o shot Rodito Lasap together with you? A. No sir, they were not there anymore. They alighted one by one. .... Q. When you transferred at the back portion passing through the front seat back, were Joey and Junior whom you mentioned a while ago still in the front seat? A. They were not there anymore. Only Rodito Lasap was there. Q. You testified that your were divested the amount of P130.00. Who divested you of that amount? A. I cannot tell which one of them because I was facing down. Q. So you were not sure who divested you of the amount of P130.00? A. I am not sure. I could not determine who took the money. Q. When for the first time were you able to identify the accused, the three (3) accused here? A. I identified Ronie Agomo-o because I saw him come out from the sugarcane plantation. Q. When for the first time you come to know the name of Ronie Agomo-o? A. For long time already. COURT Q. How long before the incident on September 22, 1993 did you come to personally know Ronie Agomoo? A. About five (5) years. .... ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. You said you were confined at the Passi District Hospital for two (2) days, is that correct? A. Yes, [s]ir. Q. Immediately upon confinement at the Passi District Hospital, were there policemen who came to the hospital and investigated about the incident? A. Joely Lasap came to me. Q. What is his relation to Rodito Lasap? A. They are first cousins. Joely Lasap is a policeman of San Enrique. Q. And this Pat. Lasap investigated you at the said hospital, is that correct? A. Yes, sir. Q. When he investigated you, were you able to identify the three accused immediately? A. Yes, sir. .... COURT Q. You said awhile ago you came to know Ronie Agomo-o for the last five (5) years. How about Eddy Paneza, when for first time have you come to know him personally? A. I already know them, Your Honor.

.... Q. How about Oscar Servando, for how long have you known him? A. The same year. Q. You know Oscar Servando for the last five (5) years yet you were not able to know what was his first name? A. Because I forgot since my house is far away. .... ATTY. ACEBUQUE Q. When you first knew the three (3) accused for the last five (5) years, have you ever met them before the incident of September 22, 1993? A. Yes, sir. Q. How many times have you met the three (3) accused before the incident? A. Many times.[25] Jose Amador corroborated Agrabios testimony as to what transpired in the evening of September 22, 1993. He testified: Q On September 22, 1993 in the evening, where were you? A I was inside the jeep. Q Why were you there? A I am intending to go to Passi. Q Could you remember the name of the driver of that particular jeep where you were riding on that particular time? A Yes, sir. The name is Rodito Lasap. Q Could you likewise remember some of your co-passengers on that particular time? A There others I could remember but the others I could not. Q And at what particular time was that? A 7:30 oclock. Q While the jeep where you were riding was on its way to Passi, could you remember if there was an unusual incident that happened? A When we were about to cross at the crossing of Brgy. Mapili within the municipality of San Enrique going to Banate, three persons came out from the camp. COURT: Q What kind of camp was that? A The [t]hree persons came out from the sugarcane field. Q And what did they do? A And they pointed a gun saying This is hold-up. PROSECUTOR: Q How many were holding a gun? A One. Q Could you remember the person who was holding the gun on that particular time? A Yes, sir I could recall. Q Who was he? A Ronie Agomo-o. Q If Ronie Agomo-o is inside the Court, could you point out where is he? A Yes, sir. INTERPRETER: (Witness pointing to a person and when asked of his name answered Ronie Agomo-o). PROSECUTOR: Q How about his companions, could you remember them? A I could identify them when the police pointed them to me but during the incident I dont know them. Q Could you name the names of the two other companions? A Servando and Paneza. Q If these other two companions of Ronie Agomo-o are inside the Court, could you point out where are they now? A Yes, sir. Q Point to them. INTERPRETER: (The witness pointed to a man sitting on the right side of the bench, who, when asked of his name answered Paneza and at the left side answered Servando.)

PROSECUTOR: Q Now after Ronie Agomo-o and his companions came out of the sugarcane field and pointed out his gun, what happened further, if any? A Paneza took away P50.00 and he also got my wrist watch. Q When Paneza took your wrist watch, was it with your consent or not? A Why should I not consent because he was holding a pinote. Q If that wrist watch be shown to you, could you still remember that wrist watch? A Yes, sir. It is my watch. Q Showing to you this wrist watch, how is this related to the one you are referring to? A This is the one. There is a name de luxe. .... Q Before Paneza took your money and your watch, what did Ronie Agomo-o and his other companions were doing at that time? A They told me to get down the jeep. Q How about the driver, what was he doing at that time? A He lay down on the chair of the jeep. Q Do you know why he lay down the jeep? A Because he lost consciousness for he was shot at the chest. COURT: Q Shot by whom? A Ronie Agomo-o shot the driver. PROSECUTOR: Q Which happened first, the shooting of Rodito Lasap by Ronie Agomo-o or the taking of your watch by Paneza? A The shooting of the driver was ahead of the taking of my watch. Q Then upon taking your watch, what did you do? A They told me to go down from the jeep. Q Did you go down from the jeep? A Yes, sir. Q Then after that? A Servando frisked my waist and then he stabbed Freddie. Q That Freddie, you refer to the person of Freddie Agrabio? A Yes, sir because he was following me. Q Then what happened further, if any? A No more because Freddie ran away and I also followed Freddie.[26] As will be noted, the testimonies of Agrabio and Amador did not fit each other in every detail. For example, while Agrabio identified Eddy Paneza as the person who stabbed him,[27] Jose Amador said it was Oscar Servando.[28] Freddie Agrabio was also confused about the type of firearm Ronnie Agomo-o used, whether it was a pistolized homemade shotgun or something else.[29] Such discrepancies, however, in the testimonies of the witnesses do not detract from their truthfulness. These apparent inconsistencies may be attributed more from an honest mistake due to fleeting memory than from a deliberate intent to prevaricate. Instead of detracting from the truthfulness of the testimonies, the inconsistencies reinforce the witnesses credibility.[30] What is important is that the testimonies of these witnesses corroborated each other in material points, to wit: (a) that the passenger jeepney they were riding on was stopped on the crossing to Barangay Mapili, San Enrique by an armed man in the person of Ronnie Agomo-o, accompanied by accused-appellants Eddy Paneza and Oscar Servando; (b) that after announcing a holdup, Ronnie Agomo-o shot Rodito Lasap, the driver of the passenger jeepney; and, (c) that the accused then divested the passengers of their money and other valuables. It is settled that so long as the witnesses testimonies agree on substantial matters, the inconsequential inconsistencies and contradictions dilute neither the witnesses credibility nor the verity of their testimonies. As this Court has held: In sum, the inconsistencies referred to by the defense are inconsequential. The points that mattered most in the eyewitnesses testimonies were their presence at the locus criminis, their identification of the accusedappellant as the perpetrator of the crime and their credible and corroborated narration of accused-

appellants manner of shooting Crisanto Suarez. To reiterate, inconsistencies in the testimonies of witnesses that refer to insignificant details do not destroy their credibility. Such minor inconsistencies even manifest truthfulness and candor erasing any suspicion of a rehearsed testimony.[31] In contrast to the clear and positive identification of Freddie Agrabio and Jose Amador, accusedappellants gave nothing but alibi and denial. They gave only self-serving testimonies, corroborated only by the testimonies of their relatives. As we have held, [a]libi becomes less plausible when it is corroborated by relatives and friends who may then not be impartial witnesses.[32] Alibi is an inherently weak defense and must be rejected when the accuseds identity is satisfactorily and categorically established by the eyewitnesses to the offense,[33] especially when such eyewitnesses have no ill motive to testify falsely.[34] In the case at bar, the defense failed to show that Freddie Agrabio and Jose Amador were motivated by ill will. Furthermore, accused-appellants defense of alibi and denial cannot be believed as they themselves admitted their proximity to the scene of the crime when the offense occurred. Eddy Paneza testified that, at the time of the incident, he was in Barangay Madarag, a town within the municipality of San Enrique[35] where the robbery took place. On the other hand, Ma. Elena Servando testified that Oscar Servando went with her to gather corn in Sitio Baclayan which is also in the municipality of San Enrique. [36] For the defense of alibi to prosper, the following must be established: (a) the presence of the accusedappellant in another place at the time of the commission of the offense; and, (b) physical impossibility for him to be at the scene of the crime.[37] These requisites were not fulfilled in this case. Considering that accused-appellants themselves admitted that they were in the same municipality as the place where the offense occurred, it cannot be said that it was physically impossible for them to have committed the crime. On the contrary, they were in the immediate vicinity of the area where the robbery took place. Thus, their defense of alibi cannot prosper. Second . Accused-appellants contend that there can be no finding of conspiracy against them because the prosecution failed to establish their participation in the killing of Rodito Lasap.[38] This argument is without merit. Conspiracy exists when two or more persons come to an agreement concerning the commission of a felony and decide to commit it. It may be inferred from the acts of the accused indicating a common purpose, a concert of action, or community of interest.[39] That there was conspiracy in the case at bar is supported by the evidence on record. Freddie Agrabio testified that after shooting the driver, the accused ordered the passengers to give their money and valuables.[40] Although Freddie Agrabio could not specify who among the three divested him of his wallet because he was lying face down on the floor of the jeepney,[41] it is clear that accused-appellants took part in the robbery. Accused-appellant Paneza did not only take valuables from the passengers but also stabbed Freddie Agrabio, hitting the latter on the left elbow.[42] Jose Amador identified both accused-appellants Eddy Paneza as the one who took his wrist watch and wallet while simultaneously pointing a pinote at him,[43] and Servando as the one who frisked his waist as he was alighting from the jeepney.[44] Clearly, therefore, accused-appellants cooperated with one another in order to achieve their purpose of robbing the driver and his passengers. [F]or collective responsibility to be established, it is not necessary that conspiracy be proved by direct evidence of a prior agreement to commit a crime. It is sufficient that at the time of the commission of the offense, all the accused acted in concert showing that they had the same purpose or common design or that they were united in its execution.[45] While only Ronnie Agomo-o shot and killed Rodito Lasap, accused-appellants cannot be exonerated. When conspiracy is established, all who carried out the plan and who personally took part in its execution are equally liable.[46] Accused-appellants must both also be held responsible for the death of Rodito Lasap. Third. Accused-appellants further assert that they cannot be convicted of highway robbery as the crime was not committed by at least four persons, as required in Article 306 of the Revised Penal Code.

However, highway robbery is now governed by P.D. No. 532, otherwise known as the Anti-Piracy and Anti-Highway Robbery Law of 1974. This law provides: Sec. 2. (e). Highway Robbery/Brigandage. The seizure of any person for ransom, extortion or other unlawful purposes, or the taking away of the property of another by means of violence against or intimidation of person or force upon things or other unlawful means, committed by any person on any Philippine Highway. In the case of People v. Puno,[47] it was held that P.D. No. 532 amended Art. 306 of the Revised Penal Code and that it is no longer required that there be at least four armed persons forming a band of robbers. [48] The number of offenders is no longer an essential element of the crime of highway robbery.[49] Hence, the fact that there were only three identified perpetrators is of no moment. P.D. No. 532 only requires proof that persons were organized for the purpose of committing highway robbery indiscriminately.[50] The robbery must be directed not only against specific, intended or preconceived victims, but against any and all prospective victims.[51] In this case, the accused, intending to commit robbery, waited at the Barangay Mapili crossing for any vehicle that would happen to travel along that road. The driver Rodito Lasap and his passengers were not predetermined targets. Rather, they became the accuseds victims because they happened to be traveling at the time when the accused were there. There was, thus, randomness in the selection of the victims, or the act of committing robbery indiscriminately, which differentiates this case from that of a simple robbery with homicide. Sec. 3(b) of the law provides: The penalty of reclusin temporal in its minimum period shall be imposed. If physical injuries or other crimes are committed during or on the occasion of the commission of robbery or brigandage, the penalty of reclusin temporal in its medium and maximum periods shall be imposed. If kidnapping for ransom or extortion or murder or homicide, or rape is committed as a result or on the occasion thereof, the penalty of death shall be imposed.[52] Since a homicide occurred during the commission of the highway robbery, the appropriate penalty to be imposed on accused-appellants would have been death. However, the crime was committed on September 22, 1993 when the imposition of the death penalty was suspended by the 1987 Constitution. Hence, the penalty next lower in degree, or reclusion perpetua, was correctly imposed by the trial court on accusedappellants Paneza and Servando. In accordance with our recent rulings,[53] the trial court correctly awarded P50,000.00 as civil indemnity in favor of the heirs of Rodito Lasap. WHEREFORE, the decision of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 23, Iloilo City is AFFIRMED. SO ORDERED.

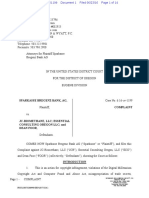

One gold bracelet P20,000.00 G.R. No. 157723 : April 30, 2009 ROMEO SAYOC y AQUINO and RICARDO SANTOS y JACOB, Petitioners, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent. DECISION TINGA, J.: This petition assails the Decision1 dated 30 January 2002 of the Court of Appeals which affirmed the Decision2 dated 25 November 1999 of the Regional Trial Court finding the accused guilty beyond reasonable doubt for violation of Presidential Decree No. 532, otherwise known as the Anti-Highway Robbery Law of 1974, and the Resolution3 dated 14 October 2002 denying the motion for reconsideration.4 The facts, culled from the records, are as follows: In the afternoon of 4 March 1999, Elmer Jaen (Jaen) was aboard a bus when a fellow passenger announced a hold-up. Three (3) persons then proceeded to divest the passengers of their belongings. Under knife-point, purportedly by a man later identified as Ricardo Santos (Santos), Jaen's necklace was taken by Santos' cohort Teodoro Almadin (Almadin). The third robber, Romeo Sayoc (Sayoc), meanwhile, reportedly threatened to explode the hand grenade he was carrying if anybody would move. After taking Jaen's two gold rings, bracelet and watch, the trio alighted from the bus. PO2 Remedios Terte (police officer), who was a passenger in the same bus, ran after the accused, upon hearing somebody shouting about a hold-up. Sayoc was found by the police officer hiding in an "ownertype" jeep. The latter instructed Jaen to guard Sayoc while she pursued the two robbers. Sayoc was then brought to the police station. A few hours later, barangay officials arrived at the police station with Santos and Almadin. They reported that the two accused were found hiding inside the house of one Alfredo Bautista but were prevailed upon to surrender. The victim's bracelet was recovered from Santos while the two rings were retrieved from Almadin. On 8 March 1999, an information was filed against the accused in the Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, which reads: Criminal Case No. Q-99-81757 That on or about the 4th day of March 1999 in Quezon City, Philippines, the above-named accused armed with [a] deadly weapon[,] conspiring, confederating with and mutually helping one another with intent to gain and by means of force and intimidation against person [sic] did then and there [willfully], unlawfully and feloniously rob one ELMER JAEN Y MAGPANTAY in the manner as follows: said accused pursuant to their conspiracy boarded a passenger bus and pretended to be passengers thereof and upon reaching EDSA Balintawak[,] a public highway, Brgy. Apolonio Samson, this city,[sic] announce the hold-up and with the use of a knife poked[,] it against herein complainant and took, robbed and carried away the following: On 30 January 2002, the Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court's decision. The appellate court viewed the alleged inconsistencies between the testimonies of the victim and the police officer as a minor variation which tends to strengthen the probative value of their testimonies. Anent the issue of illegal arrest, the appellate court concluded from evidence that Almadin and Santos voluntarily surrendered.8 In their motion for reconsideration,9 petitioners reiterated that the inconsistencies in the testimonies of the victim and the police officer refer to substantial matters, as they establish the lack of positive and convincing identification of the petitioners. On 14 October 2002, the Court of Appeals issued a Resolution denying the motion for reconsideration for lack of merit. Two gold rings 8,000.00 One Guess watch 4,000.00 Total P32,000.00 Belonging to Elmer Jaen y Magpantay in the total amount of P32,000.00 Phiippine Currency to the damage and prejudice of said offended party in the aforementioned amount of P32,000.00 Philippine Currency. CONTRARY TO LAW5 When arraigned, petitioners pleaded not guilty. After arraignment however, Almadin "jumped bail." Santos denied knowing his co-accused and his complicity in the hold-up. He declared that he was engaged in a drinking session with his kumpare Alfredo Bautista when he went up to the comfort room to relieve himself. He was suddenly dragged by the barangay officials, who hit him in the head rendering him unconscious. He was later brought to a hospital for treatment. For his part, Sayoc disclaimed knowing the other accused. He claimed to be a passenger on the said bus when the hold-up was announced. Upon seeing a person holding a gun, he immediately descended from the bus. According to Sayoc, he entered a street where vehicles were passing. As the persons who were running passed by him, he went to the side and stood up behind a wall. Soon thereafter, he was apprehended by a police officer. On 25 November 1999, the RTC rendered judgment against the petitioners and sentenced them to suffer imprisonment from twelve (12) years and one (1) day of reclusion temporal, as minimum to seventeen (17) years, four (4) months and one (1) day of reclusion temporal, as maximum. They were also ordered to pay jointly and severally the amount of P4,500.00 to the victim.6 The trial court gave full credence to the testimonies of the prosecution. It noted that the defenses raised by petitioners, which were not corroborated, cannot prevail over the clear and positive identification made by the complainant. The trial court also pointed out that the prosecution's witnesses "did not have any motive to perjure against the petitioners." Petitioners appealed to the Court of Appeals, ascribing as errors, the conclusions of the trial court on the following issues, namely: (1) the positive identification of the perpetrators; (2) the accordance of evidentiary weight to the conflicting testimonies of the victim and the police officer; (3) the disregard of evidence adduced by Sayoc; and (4) the failure to declare as illegal the arrest of Santos.7

Petitioners filed the instant petition,10 relying on the same arguments presented before the lower courts. Petitioners again raise as issues the credibility of the prosecution witnesses with respect to the identification of the perpetrators, the legality of their arrest and the failure of the judgment of conviction in stating the legal basis in support thereof.11 Settled is the rule that in criminal cases in which the penalty imposed is reclusion temporal or lower, all appeals to this Court may be taken by filing a petition for review on certiorari, raising only questions of law.12 It is evident from this petition that no question of law is proffered by petitioners. The principal issue involved is the credibility of the prosecution witnesses. It bears stressing that in criminal cases, the assessment of the credibility of witnesses is a domain best left to the trial court judge. And when his findings have been affirmed by the Court of Appeals, these are generally binding and conclusive upon this Court.13 The rationale of this rule lies on the fact that the matter of assigning values to declarations on the witness stand is best and most commonly performed by the trial judge who is in the best position to assess the credibility of the witnesses who appeared before his sala, as he had personally heard them and observed their deportment and manner of testifying during the trial.14 The findings of fact made by the trial court were substantially supported by evidence on record. Therefore, we are constrained not to disturb its factual findings. Petitioners contend that the identification made by the prosecution witnesses is not positive, clear and convincing. They argue that extreme fear, stress and anxiety may have contributed to the hazy recollection of the victim pertaining to the identification of the perpetrators. With respect to the police officer, on the other hand, petitioners insist that the former did not personally see the petitioners actually committing the crime charged. Petitioners' weak denial, especially when uncorroborated, cannot overcome the positive identification of them by the prosecution witnesses. As between the positive declarations of the prosecution witnesses and the negative statements of the accused, the former deserve more credence and weight.15 As found by the trial court, Jaen and the police officer were able to identify the petitioners, as among those who staged the robbery inside the bus, thus: Based on the testimonies of the complainant and PO1 Remedios Terte, the accused were clearly and positively identified as the three men who staged the robbery/ hold-up inside the California bus. It was Ricardo Santos who announced the hold-up after which he pointed a knife at the neck of the complainant while Teodoro Almadin divested him of his jewelry. Romeo Sayoc held everyone at bay by threatening to explode a hand grenade if anyone moved.16 Petitioners also anchor their defense on the alleged inconsistencies of the testimonies of the prosecution witnesses, such as: 1. During the direct examination, the police officer testified that she was seated on the first row at the driver's side, while on cross-examination, she stated that she was actually seated on the seventh row;17 2. On direct examination, the police officer testified that when somebody announced the holdup, the latter was seated on the right side of the bus near her, on cross-examination however, she stated that her back was turned against the person who announced the holdup;18 3. On cross-examination, the police officer stated that after the holdup, one civilian together with the victim alighted from the bus. However, the victim did not mention any civilian who got off the bus with him;19 4. The police officer averred that after the holdup, about three (3) persons proceeded towards the direction of Cubao, only to retract her statement later, to the effect that these persons turned left towards a street;20 5. During the cross-examination, the police officer witnessed a civilian calling 117 while she was running after the perpetrators. This was not mentioned in her direct-examination. Jaen, on the other hand, never mentioned such call.21

6. The police officer testified during the direct examination that she saw Sayoc "inside" an "owner-type" jeep, only to change it later to "underneath" the vehicle.22 7. The victim testified that it took the petitioners five to ten minutes to rob him while the police officer stated that it took them about five minutes.23 The variance in the testimonies of the prosecution witnesses is too trivial to affect their credibility. This Court maintains that minor inconsistencies in the narration of a witness do not detract from its essential credibility as long as it is on the whole coherent and intrinsically believable. Inaccuracies may in fact suggest that the witness is telling the truth and has not been rehearsed as it is not to be expected that he will be able to remember every single detail of an incident with perfect or total recall. The positive identification of the petitioners as perpetrators made by the victim himself and the police officer cannot be overthrown by the weak denial and alibi of petitioners. Moreover, there is no shred of evidence to show that the police officer was actuated by improper motives to testify falsely against the petitioners. Her testimony deserves great appreciation in light of the presumption that she is regularly performing her duties. The contention of Santos that he was illegally arrested and searched deserves scant consideration. As held by the trial court, Santos was not arrested, instead, he voluntarily surrendered to the barangay officials, and no countervailing evidence to dispute this fact appears from the record. Finally, petitioners argue that the appellate court's decision failed to conform to the standards set forth in Section 14,24 Art. VIII of the 1987 Constitution and Section 2,25 Rule 120 of the Rules of Court. We are not convinced. The appellate court did not merely quote the facts presented by the trial court, it arrived at its own findings. After citing and evaluating the evidence and arguments presented by both parties, the appellate court favored the prosecution. It dealt with the issues submitted by petitioners, albeit in a concise manner. This constitutes sufficient compliance with the constitutional and statutory mandate that a decision must state clearly and distinctly the facts and law on which it is based. We disagree, however, with the penalty imposed by the lower court. The penalty for simple highway robbery is reclusion temporal in its minimum period. However, consonant with the ruling in the case of People v. Simon,26 since P.D. No. 532 is a special law which adopted the penalties under the Revised Penal Code in their technical terms, with their technical signification and effects, the indeterminate sentence law is applicable in this case. Accordingly, for the crime of highway robbery, the indeterminate prison term is from seven (7) years and four (4) months of prision mayor, as minimum, to thirteen (13) years, nine (9) months and ten (10) days of reclusion temporal, as maximum.27 WHEREFORE, this Court AFFIRMS WITH MODIFICATION the findings of fact and conclusions of law in the Decision dated 30 January 2002 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CR No. 24140, finding appellants Romeo Sayoc and Ricardo Santos guilty beyond reasonable doubt of simple highway robbery. Appellants are hereby sentenced to the indeterminate penalty of seven (7) years and four (4) months of prision mayor, as minimum, to thirteen (13) years, nine (9) months and ten (10) days of reclusion temporal, as maximum, and to pay jointly and severally the amount of P4,500.00 to the private complainant, Elmer Jaen as their civil liability, with legal interest from the filing of the Information until fully paid. Since appellants are detention prisoners, they shall be credited with the period of their temporary imprisonment. SO ORDERED.

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila SECOND DIVISION G.R. No. L-28547 February 22, 1974 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ELIAS JARANILLA, RICARDO SUYO, FRANCO BRILLANTES and HEMAN GORRICETA, accused. ELIAS JARANILLA, RICARDO SUYO, and FRANCO BRILLANTES, defendants-appellants. AQUINO, J.: This is an appeal of defendants Elias Jaranilla, Ricardo Suyo and Franco Brillantes from the decision of the Court of First Instance of Iloilo, which convicted them of robbery with homicide, sentenced each of them to reclusion perpetua and ordered them to pay solidarily the sum of six thousand pesos to the heirs of Ramonito Jabatan and the sum of five hundred pesos to Valentin Baylon as the value of fighting cocks (Criminal Case No. 11082).chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library The evidence for the prosecution shows that at around eleven o'clock in the evening of January 9, 1966, Gorriceta, who had just come from Fort San Pedro in Iloilo City, was driving a Ford pickup truck belonging to his sister, Remia G. Valencia. While he was in front of the Elizalde Building on J. M. Basa Street, he saw Ricardo Suyo, Elias Jaranilla and Franco Brillantes. They hailed Gorriceta who stopped the truck. Jaranilla requested to bring them to Mandurriao, a district in another part of the city. Gorriceta demurred. He told Jaranilla that he (Gorriceta) was on his way home.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Jaranilla prevailed upon Gorriceta to take them to Mandurriao because Jaranilla ostensibly had to get something from his uncle's place. So, Jaranilla, Brillantes and Suyo boarded the pickup truck which Gorriceta drove to Mandurriao.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Upon reaching Mandurriao, Gorriceta parked the truck at a distance of about fifty to seventy meters from the provincial hospital. Jaranilla, Suyo and Brillantes alighted from the vehicle. Jaranilla instructed Gorriceta to wait for them. The trio walked in the direction of the plaza. After an interval of about ten to twenty minutes, they reappeared. Each of them was carrying two fighting cocks. They ran to the truck.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Jaranilla directed Gorriceta to start the truck because they were being chased. Gorriceta drove the truck to Jaro (another district of the city) on the same route that they had taken in going to Mandurriao.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library It is important to note the positions of Gorriceta and his three companions on the front seat of the track. Gorriceta the driver, was on the extreme left. Next to him on his right was Suyo. Next to Suyo was Brillantes. On the extreme right was Jaranilla.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library While the truck was traversing the detour road near the Mandurriao airport, then under construction, Gorriceta saw in the middle of the road Patrolmen Ramonito Jabatan and Benjamin Castro running towards them. Gorriceta slowed down the truck after Patrolman Jabatan had fired a warning shot and was signalling with his flashlight that the truck should stop. Gorriceta stopped the truck near the policeman. Jabatan approached the right side of the truck near Jaranilla and ordered all the occupants of the truck to go down. They did not heed the injunction of the policeman.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Brillantes pulled his revolver but did not fire it. Suyo did nothing. Jaranilla, all of a sudden, shot Patrolman Jabatan. The shooting frightened Gorriceta. He immediately started the motor of the truck and

drove straight home to La Paz, another district of the city. Jaranilla kept on firing towards Jabatan.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Jaranilla, Suyo and Brillantes alighted in front of Gorriceta's house. Gorriceta parked the truck inside the garage. Jaranilla warned Gorriceta not to tell anybody about the incident. Gorriceta went up to his room. After a while, he heard policemen shouting his name and asking him to come down. Instead of doing so, he hid in the ceiling. It was only at about eight o'clock in the morning of the following day that he decided to come down. His uncle had counselled him to surrender to the police. The policemen took Gorriceta to their headquarters. He recounted the incident to a police investigator.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Victorino Trespeces, whose house was located opposite the house of Valentin Baylon on Taft Street in Mandurriao, testified that before midnight of January 9, 1966, he conducted a friend in his car to the housing project in the vicinity of the provincial hospital at Mandurriao. As he neared his residence, he saw three men emerging from the canal on Taft Street in front of Baylon's house. He noticed a red Ford pickup truck parked about fifty yards from the place where he saw the three men. Shortly thereafter, he espied the three men carrying roosters. He immediately repaired to the police station at Mandurriao. He reported to Patrolmen Jabatan and Castro what he had just witnessed. The two policemen requested him to take them in his car to the place where he saw the three suspicious-looking men. Upon arrival thereat, the men and the truck were not there anymore.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Trespeces and the policemen followed the truck speeding towards Jaro. On reaching the detour road leading to the airport, the policemen left the car and crossed the runway which was a shortcut. Their objective was to intercept the truck. Trespeces turned his car around in order to return to Mandurriao. At that moment he heard gunshots. He stopped and again turned his car in the direction where shots had emanated. A few moments later, Patrolman Castro came into view. He was running. He asked Trespeces for help because Jabatan, his comrade, was wounded. Patrolman Castro and Trespeces lifted Jabatan into the car and brought him to the hospital. Trespeces learned later that Jabatan was dead.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Doctor Raymundo L. Torres, the chief medico-legal officer of the Iloilo City police department, conducted an autopsy on the remains of Patrolman Jabatan. He found: (1) Contusion on left eyebrow.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library (2) Bullet wound one centimeter in diameter, penetrating left anterior axilla, directed diagonally downward to the right, perforating the left upper lobe of the lungs through and through, bitting the left pulmonary artery and was recovered at the right thoracic cavity; both thoracic cavity was full of blood. Cause of death: Shock, hemorrhage, secondary to bullet wound. Valentin Baylon, the owner of the fighting cocks, returned home at about six o'clock in the morning of January 10, 1966. He discovered that the door of one of his cock pens or chicken coops (Exhs. A and A-1) was broken. The feeding vessels were scattered on the ground. Upon investigation he found that six of his fighting cocks were missing. Each coop contained six cocks. The coop was made of bamboo and wood with nipa roofing. Each coop had a door which was locked by means of nails. The coops were located at the side of his house, about two meters therefrom.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Baylon reported the loss to the police at Mandurriao. At about ten o'clock, a group of detectives came to his house together with the police photographer who took pictures of the chicken coops. The six roosters were valued at one hundred pesos each. Two days later, he was summoned to the police station at

Mandurriao to identify a rooster which was recovered somewhere at the airport. He readily identified it as one of the six roosters which was stolen from his chicken coop (Exh. B).chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Gorriceta, Jaranilla, Suyo and Brillantes were charged with robo con homicidio with the aggravating circumstances of use of a motor vehicle, nocturnity, band, contempt of or with insult to the public authorities and recidivism. The fiscal utilized Gorriceta as a state witness. Hence, the case was dismissed as to him.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library On February 2, 1967, after the prosecution had rested its case and before the defense had commenced the presentation of its evidence, Jaranilla escaped from the provincial jail. The record does not show that he has been apprehended.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library The judgment of conviction was promulgated as to defendants Suyo and Brillantes on October 19, 1967 when it was read to them in court. They signed at the bottom of the last page of the decision. There was no promulgation of the judgment as to Jaranilla, who, as already stated, escaped from jail (See Sec. 6, Rule 120, Rules of Court).chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library However, the notice of appeal filed by defendants' counsel de oficio erroneously included Jaranilla. Inasmuch as the judgment has not been promulgated as to Jaranilla, he could not have appealed. His appeal through counsel cannot be entertained. Only the appeals of defendants Suyo and Brillantes will be considered.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library In convicting Suyo, Jaranilla and Brillantes of robo con homicidio, the trial court assumed that the taking of the six fighting cocks was robbery and that Patrolman Jabatan was killed "by reason or on the occasion of the robbery" within the purview of article 294 of the Revised Penal Code.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library In this appeal the appellants contend that the trial court erred in not finding that Gorriceta was the one who shot the policeman and that Jaranilla was driving the Ford truck because Gorriceta was allegedly drunk. Through their counsel de oficio, they further contend that the taking of roosters was theft and, alternatively, that, if it was robbery, the crime could not be robbery with homicide because the robbery was already consummated when Jabatan was killed.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library After evaluating the testimonies of Gorriceta and Brillantes as to who was driving the truck and who shot policeman, this Court finds that the trial court did not err in giving credence to Gorriceta's declaration that he was driving the truck at the time that Jaranilla shot Jabatan.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library The improbability of appellants' theory is manifest. The truck belonged to Gorriceta's sister. He was responsible for its preservation. He had the obligation to return it to his sister in the same condition when he borrowed it. He was driving it when he saw Brillantes, Jaranilla and Suyo and when he allegedly invited them for a paseo. There is no indubitable proof that Jaranilla knows how to drive a truck.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library The theory of the defense may be viewed from another angle. If, according to the appellants, Gorriceta asked Jaranilla to drive the truck because he (Gorriceta) was drunk then that circumstance would be inconsistent with their theory that Gorriceta shot Jabatan. Being supposedly intoxicated, Gorriceta would have been dozing when Jabatan signalled the driver to stop the truck and he could not have thought of killing Jabatan in his inebriated state. He would not have been able to shoot accurately at Jabatan. But the

fact is that the first shot hit Jabatan. So, the one who shot him must have been a sober person like Jaranilla.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Moreover, as Jaranilla and his two comrades were interested in concealing the fighting cocks, it was Jaranilla, not Gorriceta, who would have the motive for shooting Jabatan. Consequently, the theory that Gorriceta shot Jabatan and that Jaranilla was driving the truck appears to be plausible.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Was the taking of the roosters robbery or theft? There is no evidence that in taking the six roosters from their coop or cages in the yard of Baylon's house violence against or intimidation of persons was employed. Hence, article 294 of the Revised Penal Code cannot be invoked.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Neither could such taking fall under article 299 of the Revised Penal Code which penalizes robbery in an inhabited house (casa habitada), public building or edifice devoted to worship. The coop was not inside Baylon's house. Nor was it a dependency thereof within the meaning of article 301 of the Revised Penal Code.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library Having shown the inapplicability of Articles 294 and 299, the next inquiry is whether the taking of the six roosters is covered by article 302 of the Revised Penal Code which reads: chanrobles virtual law library ART. 302. Robbery in an uninhabited place or in private building.-Any robbery committed in an uninhabited place or in a building other than those mentioned in the first paragraph of article 299, if the value of the property exceeds 250 pesos, shall be punished by prision correccional in its medium and maximum periods provided that any of the following circumstances is present: 1. If the entrance has been effected through any opening not intended for entrance or egress.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library 2. If any wall, roof, floor or outside door or window has been broken.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library 3. If the entrance has been effected through the use of false keys, picklocks or other similar tools.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library 4. If any door, wardrobe, chest, or any sealed or closed furniture or receptacle has been broken.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library 5. If any closed or sealed receptacle, as mentioned in the preceding paragraph, has been removed, even if the same be broken open elsewhere.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library xxx xxx xxx In this connection, it is relevant to note that there is an inaccuracy in the English translation of article 302. The controlling Spanish original reads: ART. 302. Robo en lugar no habitado o edificio particular.-El robo cometido en un lugar no habitado o en un edificio que no sea de los comprendidos en el parrafo primero del articulo 299, ... . (Tomo 26, Leyes Publicas 479). The term "lugar no habitado" is erroneously translated. as "uninhabited place", a term which may be confounded with the expression "uninhabited place" in articles 295 and 300 of the Revised Penal Code, which is the translation of despoblado and which is different from the term lugar no habitado in article 302. The term lugar no habitado is the antonym of casa habitada (inhabited house) in article 299.chanroblesvirtualawlibrary chanrobles virtual law library