Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jump Ahead and Take The Risk

Загружено:

fauno_ScribdИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jump Ahead and Take The Risk

Загружено:

fauno_ScribdАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

17-01-2011

EBSCOhost

Record: 1 Title: Author(s): Source: Peer Reviewed: ISSN: Descriptors: Jump Ahead and Take the Risk. Rudaitis, Cheryl, Comp. Teaching Music, v2 n5 p34-35 Apr 1995. N/A 1069-7446 Classroom Techniques, Discovery Learning, Educational Theories, Elementary Education, Harmony (Music), Improvisation, Learning Activities, Music Education, Music Techniques, National Programs, Orff Method, Rhythm (Music), Teacher Attitudes, Teacher Behavior, Teaching Methods, Tempo (Music), Elementary Education Arts Education National Standards, Orff (Carl) Maintains that nothing requires more meticulous preparation than guiding and supervising lessons in discovery and improvisation. Discusses the discovery learning techniques of the Orff-Schulwerk method of music instruction. Includes a teaching example based on the National Standards for Arts Education. (CFR) Theme issue topic: "Focus on Improvisation." Journal availability: Music Educators Natl. Conference, 1806 Robert Fulton Dr., Reston, VA 220914348. English Teachers; Practitioners Reports - Descriptive; Guides - Classroom - Teacher; Journal Articles Not available from ERIC CIJFEB1996 1996 EJ512725 ERIC

Identifiers: Abstract:

Notes:

Language: Intended Audience: Publication Type: Availability: Journal Code: Entry Date: Accession Number: Database:

Full Text Database: Section: Focus on IMPROVISATION GENERAL MUSIC

JUMP AHEAD AND TAKE THE RISK

"Nothing requires more meticulous preparation than guiding and supervising lessons in discovery and improvisation." American Orff teachers agree with this statement by Wilhelm Keller. They will tell you that the seeds for creating music extemporaneously should be sown in preschool and kindergarten, when instructors begin familiarizing students with the elements of music. But student preparedness, though important, is not enough; it is the teacher who holds the trump card in student improvisation success.

web.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?hid

1/4

17-01-2011

EBSCOhost

Steve Calantropio, general music teacher at the Cherry Hill School in River Edge, New Jersey, says it's especially important to prepare an improvisation lesson well. "If a teacher lacks confidence in the lesson, the students will not want to take the plunge," he said. "The kids will also have trouble focusing, which could lead to behavioral problems. The bottom line is that lessons in improvisation should not be improvised." For improvisation to work in the classroom, the teacher must be willing to take risks and be open to a broad range of possibilities, according to Carol Erion, American Orff-Schulwerk Association president. She says that because the training and experience of many teachers did not include improvisation, they may feel uncomfortable improvising with their students. If this is the case, Erion advises teachers to seek out opportunities to work on this skill. Experimenting with the voice or their instrument of choice and taking Orff teacher training courses are two suggestions. In Orff training, teachers build improvisation skills by starting with single elements and narrow parameters and gradually expanding the possibilities. With these kinds of experiences, it is easy for teachers to design sequential lessons in improvisation for their students. While the thought of teaching improvisation may be a little intimidating, the benefits to students are many, asserts Doug Goodkin, a music teacher at The San Francisco School in San Francisco, California. "Since improvisation is the jumping-off place from imitation to creation, it directly involves the student in the music-making process. Improvisation can provide the student with a sense of ownership and pride in his or her work. When a student improvises, all the lights are on--thinking, hearing, feeling, and doing. Because they're so completely engaged, most students love to improvise. However, improvisation also means jumping ahead and taking a risk in front of one's peers. Some students--shy children and middle school students--prefer the safety and comfort of the right answer." Another important function of improvisation is assessment. Goodkin says, "It's possible for a student to cram for a test, take it the next day, do well, and then forget the material he or she has learned. Improvisation is an honest assessment tool, exposing the extent of the student's understanding of the musical ideas and skills introduced by the teacher." Judith Thomas, an Orff-Schulwerk specialist at Upper Nyack Elementary School in Nyack, New York, says a teacher should begin teaching improvisation by modeling the desired technique and then inviting the class to try it. "The teacher must show confidence and warmth," she stressed. "If the teacher projects any vibes of tension, the class will pick up on those right away." ORFF Teachers Have Their Students improvise movements, rhythms, melodies, songs, and different harmonic accompaniments. Language and poetry are often the center from which the improvisations develop. As Goodkin describes the process: "I might begin my first class asking each child's name and then expressing it in a variety of ways--clapping or patting the rhythm, gesturing, or speaking it expressively--with the group imitating. After sufficient imitation, I ask, 'Does anyone else have an idea of how to play this

web.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?hid 2/4

17-01-2011

EBSCOhost

name?' From names, we move into chants, nursery rhymes, and poems. At the end of the process, small groups of children can take a poem away to a corner of the room and come back with their own composition that might include an original melody and accompaniment, movement, and drama." According to Calantropio, structuring improvisation is critical for student success. "Too many musical elements to pick from is worse than too few," he said. "It's important to limit how much students have to do; a rondo form usually works well." Goodkin agrees. "It's scary for students to have too wide a choice. If I ask a student to go to the middle of the room and improvise a dance, he or she will naturally be hesitant. But if I establish a form and invite a variation--as in teaching a set folk dance and then having the students substitute their own motions within the given form--the task is more manageable. Similarly, when I want students to improvise melodically, I begin with a small range of time and pitch, as in creating an eight-beat melodic pattern with three given notes." While Improvisation May Sometimes be taught as an isolated skill, Orff teachers usually integrate improvisation into the context of the music or the musical concepts the class is working on, says Erion. "Improvisation is not a separate unit in my curriculum, but is woven into the fabric of every class," Goodkin said. Thomas adds, "A knowledge of improvisation contributes to a student's overall musicality. Since improvisation is just a step away from a fixed piece, it's a little like feeling the fabric before you cut out the dress." Erion concludes, "Improvisation overlays the whole aesthetic of Orff-Schulwerk. It helps students develop the ability to 'think with the ears of a composer,' a goal of Orff-Schulwerk described by Carl Orff himself." ILLUSTRATION: Children often create music based on the rhythm patterns of names and other words. ~~~~~~~~ Compiled by Cheryl Rudaitis, MENC staff. MUSIC TEACHING EXAMPLE Grades K--4, Standard 3a Improvising melodies, variations, and accompaniments: Students improvise "answers" in the same style to given rhythmic and melodic phrases. During a review of body percussion echoes, students are invited to improvise their own rhythm patterns in response to the teacher rather than imitating exactly what they hear. After practice, the class is divided into two groups. Two classroom timpani (or hand drums) are placed opposite one another a few feet apart, and the students line up behind them. Using a third

web.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?hid 3/4

17-01-2011

EBSCOhost

drum, the teacher plays a "question" rhythm and, one at a time, the drummers "answer" by improvising a rhythm pattern that is the same length (eight beats) as the teachers "question." As students become more comfortable with their improvised rhythms, one drum is designated as the "question" and the other as the "answer." As each student comes to the head of the line, he or she takes a turn improvising the part assigned to the drum and then immediately hands the mallet to the next person in line. On another day, the students continue their question-and-answer improvisations in small groups, assigning two timbres of their choice to the question-and-answer players. The teacher next helps the students transfer question-and-answer improvisations to the recorder. Students echo the teacher in short melodic patterns, using a limited range of pitches (three to five, depending on the students' skill level). When the students are secure, the teacher encourages them to improvise their own answers rather than imitate the pattern he or she plays. Students, playing in small groups, respond with "answer" patterns or phrases to build confidence before playing individually. The instructional activity is successful when: The students improvise a new pattern rather than imitating what they hear The students exhibit understanding of phrase or pattern length, steady beat, and antecedent and consequent phrases or patterns in their improvisations Teaching example excerpted from MENC's Teaching Examples: Ideas for Music Educators (1994) Copyright of Teaching Music is the property of Sage Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

web.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?hid

4/4

Вам также может понравиться

- Grammar Outline ContentДокумент3 страницыGrammar Outline Contentfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Dorian Mode in All KeysДокумент3 страницыDorian Mode in All Keysfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Phrygian Mode in All KeysДокумент2 страницыPhrygian Mode in All Keysfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Mixolydian Mode in All KeysДокумент3 страницыMixolydian Mode in All Keysfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Missouri Motor Vehicle Power of Attorney FormДокумент1 страницаMissouri Motor Vehicle Power of Attorney Formfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Daniel Smith Extra Fine Watercolors - BLICK Art MaterialsДокумент11 страницDaniel Smith Extra Fine Watercolors - BLICK Art Materialsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Ionian Mode in All KeysДокумент2 страницыIonian Mode in All Keysfauno_Scribd100% (1)

- Aeolian Mode in All KeysДокумент2 страницыAeolian Mode in All Keysfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Locrian Mode in All KeysДокумент2 страницыLocrian Mode in All Keysfauno_Scribd100% (1)

- Lydian Mode in All KeysДокумент2 страницыLydian Mode in All Keysfauno_Scribd100% (2)

- Gospels. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2016. (ISBN 978-1451465457)Документ7 страницGospels. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2016. (ISBN 978-1451465457)fauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Políticas de ReservaДокумент12 страницPolíticas de Reservafauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Landscape Painting With Doug ReinaДокумент1 страницаLandscape Painting With Doug Reinafauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Winsor & Newton Professional Watercolor Tubes - BLICK Art MaterialsДокумент7 страницWinsor & Newton Professional Watercolor Tubes - BLICK Art Materialsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Transcription TagsДокумент1 страницаTranscription Tagsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Transcription TagsДокумент1 страницаTranscription Tagsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Carretera Austral: 1. Chiloé IslandДокумент3 страницыCarretera Austral: 1. Chiloé Islandfauno_Scribd0% (1)

- Winsor & Newton Artists' Watercolor Brushes - BLICK Art MaterialsДокумент2 страницыWinsor & Newton Artists' Watercolor Brushes - BLICK Art Materialsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Guffey Syllabus Jesus Gospels 2018Документ14 страницGuffey Syllabus Jesus Gospels 2018fauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- SC 540 Synoptic Gospels Final Syllabus Sp2015Документ10 страницSC 540 Synoptic Gospels Final Syllabus Sp2015fauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- WYB1501HF From The Gospel To The Gospels SyllabusДокумент5 страницWYB1501HF From The Gospel To The Gospels Syllabusfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- 22200: Intro To The New Testament Sample Syllabus: Center For Student Success, NRT 154 Telephone: 502-897-4680Документ6 страниц22200: Intro To The New Testament Sample Syllabus: Center For Student Success, NRT 154 Telephone: 502-897-4680fauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Grace Communion Seminary Nt502 Gospels Short Syllabus For Fall 2015 Instructor: Michael Morrison, PHD Phone: 626-650-2363 Course DescriptionДокумент5 страницGrace Communion Seminary Nt502 Gospels Short Syllabus For Fall 2015 Instructor: Michael Morrison, PHD Phone: 626-650-2363 Course Descriptionfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- College of General Studies: Course Syllabus - Section IДокумент7 страницCollege of General Studies: Course Syllabus - Section Ifauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Synoptic Gospels: MHRB) NB DWD NB W (#Y TWDLWT HL)Документ5 страницSynoptic Gospels: MHRB) NB DWD NB W (#Y TWDLWT HL)fauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- SC-540 The Synoptic Gospels Syllabus 2018: I. Course DescriptionДокумент11 страницSC-540 The Synoptic Gospels Syllabus 2018: I. Course Descriptionfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- 4 Gospels SyllabusДокумент1 страница4 Gospels Syllabusfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Syllabus: Gospels: 06NT5200 - S 2020 A. Purpose and DescriptionДокумент6 страницSyllabus: Gospels: 06NT5200 - S 2020 A. Purpose and Descriptionfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- Bi6623 Studies in The Gospels and Acts - Sample SyllabusДокумент6 страницBi6623 Studies in The Gospels and Acts - Sample Syllabusfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- GBIB 560 GospelsДокумент13 страницGBIB 560 Gospelsfauno_ScribdОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 3rdQ EXAM TLE 10Документ2 страницы3rdQ EXAM TLE 10milaflor zalsosОценок пока нет

- House of The Rising Sun ChordsДокумент2 страницыHouse of The Rising Sun ChordsTeacherОценок пока нет

- Listening and Speaking Intro Q: Skills For Success Unit 1 Student Book Answer KeyДокумент2 страницыListening and Speaking Intro Q: Skills For Success Unit 1 Student Book Answer KeySamet Kaya71% (7)

- BlazeDTV v6.0 Manual (Black)Документ14 страницBlazeDTV v6.0 Manual (Black)sakho1Оценок пока нет

- Antenna Vsat Maintenance ProposalДокумент11 страницAntenna Vsat Maintenance ProposalRachmat HidayatОценок пока нет

- IPTV Performance Monitoring: Technical ReportДокумент42 страницыIPTV Performance Monitoring: Technical ReportHoang TranОценок пока нет

- 4minute - Sweet Suga HoneyДокумент5 страниц4minute - Sweet Suga HoneyZahid NajuwaОценок пока нет

- The Music and Musical Instruments of Japan.Документ296 страницThe Music and Musical Instruments of Japan.Maria FernandaОценок пока нет

- Group 3 TourismДокумент9 страницGroup 3 Tourismradinsa yolacdОценок пока нет

- Art Apreciation Sample QuestionsДокумент2 страницыArt Apreciation Sample QuestionsJam LarsonОценок пока нет

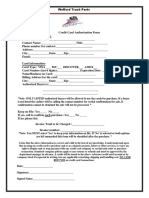

- Credit Card Authorization Form WoffordДокумент1 страницаCredit Card Authorization Form WoffordRaúl Enmanuel Capellan PeñaОценок пока нет

- License Agreement: and Non-Exclusively Licensed By: Lê PhúC Artist Name: Merz From Licensor: Cymatics LLCДокумент3 страницыLicense Agreement: and Non-Exclusively Licensed By: Lê PhúC Artist Name: Merz From Licensor: Cymatics LLCMerz100% (1)

- Foolscap FolioДокумент2 страницыFoolscap FolioSpiegel SpassОценок пока нет

- Creating A Bootable DOS CD V 1.5Документ25 страницCreating A Bootable DOS CD V 1.5DooLooОценок пока нет

- Jessie J LetrasДокумент30 страницJessie J LetrasJaymes Mour GómezОценок пока нет

- LG CM4330 PDFДокумент67 страницLG CM4330 PDFFrancisco Javier Puentes Sandoval0% (1)

- Lesson 15 - Sound Collage Project HandoutДокумент4 страницыLesson 15 - Sound Collage Project HandoutIan BurnsОценок пока нет

- O Rings ChartДокумент4 страницыO Rings ChartSuresh Kumar MittapalliОценок пока нет

- 750G HDDДокумент9 страниц750G HDDMoses AbdulkassОценок пока нет

- Ballroom DancesДокумент27 страницBallroom Dancesdevanough22Оценок пока нет

- DxdiagДокумент26 страницDxdiagvalkirion shadowОценок пока нет

- Model S Owners Manual North America en Us PDFДокумент233 страницыModel S Owners Manual North America en Us PDFJason LiОценок пока нет

- Tenge SsssДокумент114 страницTenge SsssDiana Esquillo Dela Cruz100% (3)

- Katalog PRETIS 2013Документ28 страницKatalog PRETIS 2013Mirza OglečevacОценок пока нет

- Emissary v1.0.0 User ManualДокумент9 страницEmissary v1.0.0 User ManualmarcusolivusОценок пока нет

- Unit 11 - Movies m3Документ16 страницUnit 11 - Movies m3Janet DiosanaОценок пока нет

- Hindi Book Bhavan Bhaskar Vastu ShastraДокумент80 страницHindi Book Bhavan Bhaskar Vastu ShastraCentre for Traditional Education100% (1)

- Rock Project RubricДокумент4 страницыRock Project Rubricapi-281980239Оценок пока нет

- AD&D Adventure Gamebooks Sceptre of Power PDFДокумент195 страницAD&D Adventure Gamebooks Sceptre of Power PDFWerewolf67100% (2)

- 3 VR Input DevicesДокумент47 страниц3 VR Input DevicesFENGDA WUОценок пока нет