Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Model of Stress

Загружено:

Praveena ChaudharyИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Model of Stress

Загружено:

Praveena ChaudharyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

S Palmer et al

Model of organisational stress for use within an occupational health education/promotion or wellbeing programme A short communication

Stephen Palmer1, Cary Cooper2 and Kate Thomas3

Abstract This paper introduces a simple model of organisational stress which can be used to educate or inform employees, personnel and health professionals about the relationship between potential work-related stress hazards, individual and organisational symptoms of stress, negative outcomes and financial costs. The components of the model relate directly to a recent Health and Safety Executive publication1 which focuses on improving and maintaining employee health and wellbeing.

Key words: work-related stress, Health and Safety Executive, stress prevention, stress management, risk assessment

Introduction During the 1990s, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) published a number of documents which provided information for health and safety practitioners and employers on stress, stress research and stress prevention2,3,4. However, the guidance for employers lacked a structured approach for work-related stress prevention programmes although the publications highlighted many possible strategies, such as staff training and improving communication5. In 2001, the HSE1 published a guide for managers running units or departments with 50 or more staff (see endnote). The guide1 focused on the application of a structured approach to stress prevention by providing a five-step work-related stress risk assessment to aid diagnosis of the problem(s) and provide a framework for intervention. Unfortunately, from an educational viewpoint, the document did not include a model

of the Centre for Stress Management, London; Visiting Professor of Work Based Learning and Stress Management, National Centre for Work Based Learning Partnerships, Middlesex University. 2BUPA Professor of Organisational Psychology and Health, University of Manchester, Institute of Science and Technology, Manchester. 3Consultant Director, Centre for Stress Management, London. Correspondence to: Stephen Palmer, Centre for Stress Management, PO Box 26583, London UK SE3 7EZ. dr.palmer@btinternet.com

1Director

378

Health Education Journal 60 2001 378380 60(4)

Model of organisational stress A short communication

of stress to underpin the theory and practice advocated by the document. To help explain the new guidance to managers, personnel and health professionals, the authors of this paper developed a simple model of stress,6 based on earlier engineering models of stress, which includes the main stress-related hazards and outcomes discussed in the HSE document1. This model of stress was later launched at a major annual conference of personnel and development professionals6.

Model of Stress

The overall model of stress is self-explanatory. However, in the authors experience, the HSE have chosen seven key hazards that usually require further explanation depending upon the level of knowledge of the employees or professionals involved (see below). It is worth noting that 199596 figures for the financial cost of stress have been used in the model as these were the figures provided by the HSE in the document1. More recent figures provided by other organisations suggest that these are an under-estimate but the more conservative financial costs provided by the HSE were chosen to avoid any discord.

F urther information The HSE1 recommended a five-step stress risk assessment focuses on assessing and then addressing seven major hazards: Culture: of the organisation and how it deals with stress (for example, long hours culture); Demands: exposure to physical hazards and workload (for example, volume and complexity of work; shift work); Control: employee involvement with how they do their work (for example, control balanced

Health Education Journal 60 2001 378380 60(4)

379

S Palmer et al

against demands); Relationships: includes all work relationships (for example, bullying and harassment); Change: its management and communication to staff (for example, staff understanding why change is necessary); Role: employee understands role; jobs are clearly defined (for example, conflicting roles avoided); Support, training and factors unique to the individual: support from peers and line managers; training for core functions of job; catering for individual differences. The HSE1 assert that a proactive approach, as opposed to the more usual reactive approach, should be undertaken to tackle work-related stress. Therefore the focus should be on stress prevention by assessing and subsequent removal of the hazards and not stress management, pressure management training or employee stress counselling. Qualitative assessment methods to find out whether work-related stress is a problem can include performance appraisals, informal discussions with staff, focus groups, and return-to-work interviews. Quantitative methods include productivity data, sickness/ absence data, staff turnover and questionnaires1. However, the HSE do not recommend commercially available questionnaires as they may not be reliable or valid tests for work-related stress. The emphasis is on organisations developing their own audit tools with appropriate guidance. The risk assessment process in this document1 follows the principles explained in an earlier HSE publication7.

Conclusion The simple model of organisational stress proposed in this paper can be used as a training resource to educate and inform employees and key personnel about workrelated stress and can help to explain the new HSE guidelines on tackling work-related stress1. References 1 Health and Safety Executive, Tackling Work-Related Stress: A Managers Guide to Improving and Maintaining Employee Health and Well-being. Sudbury: HSE, 2001. 2 Cox T. Stress Research and Stress Management: Putting Theory to Work, CRR61. London: Health and Safety Executive, 1993. 3 Health and Safety Executive, Work-Related Factors and Ill Health: The Whitehall II Study, CRR266. Sudbury: HSE, 2000. 4 Health and Safety Executive, Stress at Work: A Guide for Employers. Sudbury: HSE, 1995. 5 Sutherland V, Cooper CL. Strategic Stress Management: An Organizational Approach. London: Macmillan Books, 2001. 6 Palmer S. Managing Stress. Conference paper given at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, Harrogate, UK, 25th October 2001. 7 Health and Safety Executive, 5 Steps to Risk Assessment, INDG163 (rev). Sudbury: HSE, 1998.

Endnote: According to the document1 the HSE guidance is not compulsory for employers. However, if employers adhere to the guidance then they are normally doing enough to comply with the law.

380

Health Education Journal 60 2001 378380 60(4)

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Jose Rizal'S Higher EducationДокумент15 страницJose Rizal'S Higher EducationSherilyn Villaverde Delmo100% (2)

- Was Al Harith Bin Kaladah The Source of The Prophets Medical KnowledgeДокумент12 страницWas Al Harith Bin Kaladah The Source of The Prophets Medical KnowledgeSalah ElbassiouniОценок пока нет

- Sub. of IntegersДокумент4 страницыSub. of IntegersJane NuñezcaОценок пока нет

- A Community-Based Mothers and Infants CenterДокумент10 страницA Community-Based Mothers and Infants CenterRazonable Morales RommelОценок пока нет

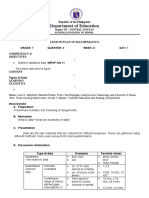

- Department of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsДокумент2 страницыDepartment of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsShiera SaletreroОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Students' Speaking SkillsДокумент6 страницEnhancing Students' Speaking SkillsWassim Kherbouche100% (1)

- Risnauli Tondang ResumeДокумент3 страницыRisnauli Tondang ResumeBoslanОценок пока нет

- States That Do Not Require The CGFNSДокумент1 страницаStates That Do Not Require The CGFNSDevy Marie Fregil Carrera100% (1)

- Chapter III: Implementing The Curriculum/Lesson 2 Level of Knowledge Learning Styles Writing Lesson Plan Level of KnowledgeДокумент8 страницChapter III: Implementing The Curriculum/Lesson 2 Level of Knowledge Learning Styles Writing Lesson Plan Level of KnowledgeNorman C. CalaloОценок пока нет

- Free Sample TOEFL Essay #3 Articles Missing + KEYДокумент2 страницыFree Sample TOEFL Essay #3 Articles Missing + KEYDobri StefОценок пока нет

- Enhancing The Reading Ability Level of Grade 1 Learners Using Downloaded, Printed Reading MaterialsДокумент37 страницEnhancing The Reading Ability Level of Grade 1 Learners Using Downloaded, Printed Reading MaterialsJANICE ANGGOTОценок пока нет

- Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Planning & Development DepartmentДокумент3 страницыGovernment of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Planning & Development DepartmentHayat Ali ShawОценок пока нет

- Relation Between ICT and DiplomacyДокумент7 страницRelation Between ICT and DiplomacyTony Young100% (1)

- TCS National Qualifier TestДокумент7 страницTCS National Qualifier TestNIKHIL GUPTAОценок пока нет

- ResourcesДокумент3 страницыResourcesapi-242658491Оценок пока нет

- The Importance of Learning and Understanding Local HistoryДокумент9 страницThe Importance of Learning and Understanding Local HistoryJessie FixОценок пока нет

- 2018 - Course Syllabus SuperLearner V2.0 Coursmos PDFДокумент17 страниц2018 - Course Syllabus SuperLearner V2.0 Coursmos PDFAli Usman Al IslamОценок пока нет

- GEC 103 - Exploring Texts and Coping With ChallengesДокумент41 страницаGEC 103 - Exploring Texts and Coping With ChallengesDale Joseph PrendolОценок пока нет

- S Upporting L Earning and T Echnology in E DucationДокумент20 страницS Upporting L Earning and T Echnology in E DucationSLATE GroupОценок пока нет

- Dream School Worksheet PDFДокумент2 страницыDream School Worksheet PDFPaula Cristina Mondaca AlfaroОценок пока нет

- اختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهДокумент31 страницаاختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهhamaidataeiОценок пока нет

- The Conqueror of Hearts by Shaykh Mustafa Kamal NaqshbandiДокумент103 страницыThe Conqueror of Hearts by Shaykh Mustafa Kamal NaqshbandiAbdul Mateen100% (1)

- Gec 6: Science, Technology & Society Handout 2: General Concepts and Sts Historical DevelopmentsДокумент8 страницGec 6: Science, Technology & Society Handout 2: General Concepts and Sts Historical DevelopmentsJoan SevillaОценок пока нет

- Icc1 Examiners Report Sept19 Final 031219 RewДокумент12 страницIcc1 Examiners Report Sept19 Final 031219 RewjyothishОценок пока нет

- 7em SocДокумент226 страниц7em Socvenkat_nsnОценок пока нет

- Organizational BehaviourДокумент5 страницOrganizational BehaviourLokam100% (1)

- Maths - Perimeter Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыMaths - Perimeter Lesson Planapi-525881488Оценок пока нет

- IMD164Документ29 страницIMD1642022488452Оценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper On Philippines System of EducationДокумент1 страницаReaction Paper On Philippines System of Educationhadassah kyleigh zhaviОценок пока нет

- DLL (Feb28 March03) Week3Документ3 страницыDLL (Feb28 March03) Week3Joy Ontangco PatulotОценок пока нет