Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

66

Загружено:

Lee Sum YinИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

66

Загружено:

Lee Sum YinАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Internationalisation and the Role of University Networks Proceedings of the 2009 EMUNI Conference on Higher Education and Research

Portoro, Slovenia, 25-26 September

DEVELOPING A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ON INTERNATIONALIZATION OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN SERBIA Jelena Vapa-Tankosic, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Economics and Management Engineering, University Business Academy 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia E mail: jvapa@libero.it

Marko Cari, Associate Professor Faculty of Economics and Management Engineering University Business Academy 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia E mail: macaric@yahoo.com Abstract The purpose of the present study is to establish a conceptual framework on internationalization of higher education in Serbia. Internalization process in higher education must support the Serbias pre-accession process for European Union membership. The setting of the conceptual framework is an integral part of an effective internalization process. This paper suggests that a conceptual framework should be based on the process of reshaping internal higher education structure and the application of the Bologna Process. On the way of reshaping internal higher education structure the internalization should be embedded in the culture, policy, planning and organizational process of the institutions. The analysis encompasses the main elements for the development of the model of internalization with an aim of facilitating the mobility and employability of Serbian students and researchers while supporting the economic development of the region.

Keywords: internalization, framework, higher education, Serbia.

INTRODUCTION

Economic and cultural globalization has imposed new challenges for the system of higher education. Yet, traditionally higher education was more internationally open because of its immersion in knowledge in line with basic freedoms of the Single Market free movement of capital, goods, services, and persons.

Every research university is part of a single worldwide network and as a result, research is more internationalized than ever before. In today global knowledge economies, higher education institutions are the key subjects that strive to implement a wide range of crossborder relationships and continuous global flows of people, information, knowledge, technologies, products and financial capital.

In an analysis of mission statements from universities throughout the world, global themes tend to dominate and the majority of universities in industrialized countries address the issue of increased international integration and the emergence of a so-called global community. Research universities are intensively linked within and between the global cities that constitute the major nodes of a networked world (Castells, 2001; McCarney, 2005).

Key analyses of internationalization in higher education point to a broad range of international dimensions in higher education (de Wit 2002; van der Wende 2001; Altbach, Teichler 2001; OECD 2004; Knight 2004). Internationalization is generally defined as increasing crossborder activities amidst persistence of borders and universities are increasingly required to provide an education that fosters global knowledge, skills and languages in order to perform professionally and socially in an international and multicultural environment. The most comprehensive definition is found in Knight (1999) "internationalization of higher education is the process of integrating an international/intercultural dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of the institution." (p. 16).

As per the term internationalization, it has been employed regarding several themes (Teichler 2007, p. 10-11) as the physical mobility, prevalently of students, but also of academic staff and occasionally administrative staff and it is included in programs aiming to promote internationalization. Various programs for the support of student mobility were established with the hope, that cognitive enhancement would be accompanied with attitudinal change: 2

growing global understanding, more favorable views of the partner country, a growing empathy with other cultures, etc.

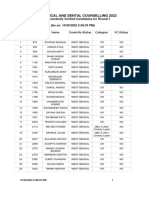

Table 1. Most Important Aspects of Internationalization

The main advantages of internalization of HE are increased mobility, trust, contact and knowledge. The particular benefits of internalization for transition countries as Djanaeva (2001) underlined include entering into the world system of academic research and innovation; increasing the mobility of students, faculty, and staff; participating in international accreditation and credit transfer; revitalizing the nation's economy; democratizing the administration of colleges and universities; broadening our understanding of academic freedom; and learning new approaches to a range of issues and problems, both academic and administrative.

1. INTERNALIZATION POLICY OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN EUROPE

Cooperation across Europes internal borders is becoming an integral part of the daily life of national universities and other higher education institutions. In 1997 the Council of Europe signed an agreement in Lisbon for a multilateral legal framework to improve international recognition of higher education and periods of study. The Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education in the European Region is known as The Lisbon Convention.

The Bologna process was launched in 1999 by 30 countries to create convergence between higher education systems as the European countries had their specific higher education systems, where degrees and academic years were inconsistent. This was aimed at establishing a single integrated framework as a European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and the international recognition of qualifications by member countries by:

National quality assurance agencies; Uniform degree structures; The adoption of a common credit transfer system; 3

A common way of describing the qualification (Diploma Supplement); A focus on lifelong learning.

The Copenhagen Process was launched in November 2002 by the ministers for education and vocational training of the European Union and the countries belonging to the European Economic Area (EEA) and the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), the European social partners and the European Commission. It led to the creation of major tools for increasing the transparency and recognition of knowledge, aptitudes and skills, and for the quality of the systems: the common European principles for the identification and validation of non-formal and informal learning, Europass, the European qualifications framework (EQF), the future European Credit system for Vocational Education and Training (ECVET), and the future European common quality assurance framework for vocational education and training.

In 2004, the EU launched the Erasmus Mundus (World) program to support master courses (joint/double degree programs) run by at least three institutions in three European countries and their exchanges with partner institutions in the third countries. The ERASMUS program managed by the European Commission has promoted and financed almost all student flows within the European Union (EU) and into the EU from the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe (prior to their joining the EU), the candidate countries of the Balkans, and some Mediterranean countries.

The strategy aims at the enhancement of the competitiveness of Europe (in productivity, employment, science and technology) and respect for the environment, as well as greater social cohesion and the realization of lifelong learning for all. In the past years, the funds allocated to education and training increased. In the 2007-13 period the total should exceed over 1% of the Community budget, compared to only 0.1% in 1986 after the Lisbon strategy was adopted, a new basis for policy co-operation was established, under the 'Education and training 2010 work program'.

2. HIGHER EDUCATION REFORMS IN SERBIA

The wars and their consequences cost Serbia a decade in its EU accession process. In the time of war and sanctions (1990s), the quality of university education in Serbia has declined 4

significantly. The primary causes of this situation were the lack of equipment, the loss of well-qualified staff (brain drain) and, most of all, the absence of sufficient funding. The crisis was also reflected onwards to the poor organization and management of HE and no general strategy.

The external institutional reports published in 2003 by the Ministry of Education and Sport list the major weaknesses of the existing academic system:

outdated and highly repetitive curricula, outdated teaching methodology, together with the outdated and internationally not relevant literature; highly structured mono-disciplinary program that cannot answer the market needs. Focus is placed on the theory, with practical skills and knowledge being neglected; long and rather difficult undergraduate studies, large dropout rate, too long actual study period, non-existent side exits. Too many teaching hours. No room for alternatives to traditional ex-cathedra teaching. Large number of exams;

weak and poorly organized post-graduate studies; non-existing quality control system and program and institution accreditation; the recognition of diplomas and certificates is left entirely to the faculty that seems to be the closest to covering those disciplines in question. The usual practice relies mostly upon counting the courses and years of studies and not looking for substantial differences (p. 13-14).

The Law on Higher Education (LHE), a legal basis for full implementation of the Bologna Declaration and the Lisbon Convention, came into effect on September 10th, 2005. The Law of Higher Education is fully compliant with the main principles of the Convention while other principles of the Convention are regulated by the statutory bylaws of all HE institutions.

After the election of the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE) and the election of members of the Commission for Accreditation and Quality Assurance (CAQA) the Accreditation Standards, compliant to the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the EHEA, were put in place. The implementation of the Bologna Process began from the academic year 2006/2007. The three-cycle structure prescribed by LHE is established in all higher education university institutions. The ECTS system is fully implemented in all HEIs 5

and the Diploma Supplement has been issued (automatically and free of charge) for the educational programs of the first and the second cycle.

The accreditation process comprises accreditation of all higher education institutions (institutional accreditation) and of all their study programs (program accreditation). Seven public universities (85 faculties), 6 universities established by non-state founders (43 faculties) and more than 80 Universities of Professional Studies are subject of compulsory national accreditation. Due to the limitation of CAQA resources, up to now the accreditation has been completed in more than 50% HEIs.

According to the national reports in regard to the Bologna process the accreditation of HEIs delivering first- cycle (bachelor), second-cycle (master) and third-cycle (PhD) of academic study programs started in February 2008. Up to now, 27 HEIs and 354 programs (first-cycle 130, second-cycle 152, and third cycle 72) have been already accredited. According to the Law, the process should be finished until October 2009. In parallel with academic accreditation, all faculties of universities have to obtain national accreditation for scientific research, not obligatory for HE institutions for professional studies.

The same report also cites that higher education in Serbia is traditionally oriented towards international collaboration with a special emphasis placed on strengthening the cooperation based on partnership and recognition of qualifications. HEIs of Serbia have had for a long time already very close relations with important research Universities form USA, Russia and China. In regard to the Bologna process and in order to increase student and staff mobility all major universities have been called to participate in mobility programs. There are also bilateral agreements on cooperation and student/staff mobility. Part of the mobilities is also carried out through international students associations (medicine, economy, pharmacy and technical sciences).

Majority of universities have adopted bylaws on student mobility and transferability of ECTS. Tempus, Erasmus Mundus and Erasmus Mundus External Windows programs have increased student and staff mobility (50 projects implemented within Tempus program) with obstacles still unfortunately related to adequate financial support and visa issue. Mobility has also been realized through research projects supported by the Ministry of Science and Technological Development. 6

The framework legislation in Serbia allows establishing joint programs and awarding joint degrees. The programs of Business administration, European studies, and Management seem to be of prevailing interest with a very few Universities that are offering it in conjunction with other European HE institutions. For now, no specific or targeted actions are taken to encourage joint programs on a national level nor there any specific support systems for students to pursue joint degree cooperation. It is a fact that the management of HE institutions themselves is interested in adoption of such programs.

3. AN INSIGHT INTO THE ISSUE OF STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT OF A INTERNATIONALISATION PROCESS

Knights (1999) developed a typology of four in order to elaborate on the approaches to internationalize. Knight (1999) presented activity approach (bringing international student body, developing or joining exchange programs) competency approach (change in the knowledge, skills, interests, values, and attitudes of different groups of in the organization), ethos approach (developing a culture and climate which facilitates internationalization) and process approach (developing an international aspects not only into academic aspects of the organization but also managerial aspect), as four basic approaches to internationalize.

The approach of Kondakci, Van den Broecke and Devos (2006) emphasizes that internationalization is not simply an issue of managing student mobility but an issue of strategic transformation of the Higher Education institutions. They argue that perceiving internationalization as a managerial issue, which touches structural-functional domains of the organization, and conceptualizing it as an organizational change process is a necessary first step toward successfully developing international dimension into core functions of a HE institutions.

Developing management practices that consider the uniqueness of each institution is crucial toward turning these organizations into effective organizations. In the internationalization process, the organizations are unlikely to identify and formally define every dimension of the change process of internationalization and the organizations continuously face with the need to modify the defined dimensions and incorporate new dimensions. The strategic plan should 7

be based on the chosen degree of internationalization and strategic planning must respond to the local campus culture, decision-making traditions, the degree of urgency, and the administrative vision, political skill, and courage at each campus (Keller, 1997, p. 163).

At the International University in Kyrgyzstan Djaneva (2001) points out to the very important fact that is quite interesting to note especially for transitional countries.

Foreign colleges exhibit a strong trend to work strategically. During our process of transforming higher education we can benefit from international experience in terms of learning and implementing the methods and systems of strategic thinking, strategic management, enhancing strategic plan development and university community's participation in this process. Our experience in empowering our faculty has revealed a strong resistance to take advantage of initiatives, a major loss of faculty commitment in decision making (due to incredibly small salaries and lack of any benefits), and an inherited tradition to be outside of the process of decision making and planning for the future. Speaking about democratization, one should mention a tradition in Western education to organize interest groups and lobby at various political levels.

To take into analysis a model of Internationalization of from the USA the Strategic Plan of Austin Peay State University (APSU) in which the Progressive scale of internalization was developed. The scale began from Isolated Implementation based on international activities currently in place and described enhancements that could be implemented by various units around the university with limited budget allocations. The second level, Cohesive Collaboration, aims to meet the goals at Level 2, which put further international activities attracting the attention of multiple parties on campus as well as some additional resources to support those efforts. The third level, Purposeful Investment, involves a commitment to augmenting internationalization and to allocating funds and resources. Building upon the prior three levels, the fourth, Actual Internationalization, reflects a diverse and multilayered approach to international education that can be a role model for other universities (p. 74-75).

4.

A BRIEF COMPARISON OF HE INTERNALIZATION IN A GLOBAL

ENVIRONMENT

Among the economically advanced large countries (US, Japan, the UK) in Europe for example, the German and French scene of internationalization is very satisfying in both successfully stimulating inwards and outwards bound mobility of students and scholars. Yet it must be noted that the internationalization is traditionally more strongly embedded in the higher education system of smaller countries in Europe (Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands or Sweden).

In regard to the USA Higher Education environment and its effect on internationalization, EIKhawas (1994) mentions four key points:

a. There is no national, governmental policy that guides campus action.

b. The main sources of advice and guidance for campus action are private.

c. The actions of each college and university with respect to international activity depend, to a substantial extent, on the decisions of institutional leaders.

d. International activities, by and large, must depend on self-financing mechanisms (p. 90).

Knight (2003) marks the general interest and activity level of Canadian universities in delivering education programs across borders is moderate to low. There is significantly more interest in the movement of students in and out of Canada than education programs. Yet she notes that this does not mean that Canada PSE institutions are not actively involved in internationalization and cross-border education. What it points to is the history and stronger orientation of Canadian institutions to international development cooperation work, which is usually characterized by capacity building and technical assistance, than to the export of education programs through franchise and twinning programs. There are instances where institutions have tried to establish a joint or double degree program as part of development/aid and mobility projects but these are few in number (p.8).

In Australian universities the prevailing model is the student mobility model and the export of higher education. In an update on the internationalization of Australian universities from the University of Melbourne (2006), it is stated that the Australian case is not one of globalization it should be regarded as a traditional import-export model for the economic benefit of Australian universities.

Kishun (2007) points out that in South Africa the most important aspect of internalization is linked to the policy and funding implications of increased emphasis on internationalization, both at the national and institutional levels. The worldwide experience is that national policies are key in providing a broad framework within which a higher education sector can strategically develop to take advantage of opportunities to internationalise. (p.10)

In 2005 Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology decided to promote a model for the strategy of internationalization of Japanese universities as they were not satisfied with the existing state. The project of International Strategy Headquarters in Universities was launched in fiscal year 2005 with funding lasting for a period of the following five years. The international strategies of the Japanese pilot universities were revealed at the public symposium at Osaka University with the most important aspects of internalization outlined:

1. organizational structure and governance

(the roles and tasks of the international

headquarters within universities, coordination between the international headquarters and faculties and administrative offices);

2. PDCA (plan-do-check-action) for the international activities (scanning the present state of its internationalization, inviting experts for the assessment of international activities and conducting surveys on faculty members, staff, and students, action plans through the process of creating a mission and master plan, defining the goals from short- to long-term);

3. acquisition of external funds;

4. formulation of and participation in the international consortia;

10

5. training and acquiring administrative staff (staff development, the active recruitment of experienced staff from the business world, and hiring staff as specialists for managing international activities);

6. internationalization at home( creating user friendly sections for international students and researchers involving general educational affairs, student services, library, and computer related facilities, effective support for international researchers and students including their families);

7. encourage Japanese students to study abroad (national universities to develop the study abroad programs);

8. development of overseas bases.

Following the project implementation in Japanese Universities it was noted that at the private universities the international education programs were linked to both the management policy and marketing strategies. The private universities have welcomed innovative study abroad programs as well as faculties and departments including their curricula, which feature international dimension, and the strong support of the corporate (management) side. There is a significant difference between private and national universities in terms of the driving force for the organizational approach to the internationalization of education, in that the major (traditional) national universities prioritize research above all other matters. (p. 230)

5. DEVELOPING AN INTERNATIONALISATION FRAMEWORK IN SERBIA

As part of the introduction of a three-tier system of academic qualifications in accordance with the Bologna agreement (bachelor, master and doctor) HE institutions in Serbia are spending considerable time and effort on the strengthening and development of cooperation with a number of universities in different parts of Europe. Internationalization is an important component in the Universitys work on quality

assurance. Research and teaching are exposed to international competition and given opportunities for cooperation should present a unique blend of inputs of different cultural experiences into higher education and research. The years of isolation and sanctions may have brought the lack of understanding of the forms of cooperation with the world while limited 11

resources may suggest that bringing international dimension into research practice may be the greatest obstacles.

International cooperation is closely connected to questions about democracy, human rights and academic freedom. The Universities should take an active interest in the integration of immigrants (ex brain drain) in Serbian society and in the adaptation of Serbian society to a multicultural reality. Abdouli (2008) points

out that the term of a complete internationalization has to be linked to the term of the real qualification and promotion of other linked sectors, especially the social and the economic sectors.

In order to meet the challenges of globalization in Serbia a more comprehensive cooperation between regional HE institutions is necessary. The regional strategy is to be based on a regional grouping of universities and institutions of higher education with an aim to cooperate in the best interest of the region. A strategy for regional internationalization involves approaching the rest of the world from a common platform of the shared regional productive partnership.

In order to make the internalization policy long-term and sustainable the University needs expertise, interest and commitment. It requires resources and a clear definition of areas of responsibility. Hiring an international coordinator should be obligatory as this objective demands constant planning including at all levels. Even the most professional international coordinator cannot make internalization happen without the involvement of faculty, staff and students.

It is essential that each University in Serbia be seen internationally as an institution with a distinct profile. While it is important to emphasize what the specific University represents as a whole the comparative advantages of each faculty, must also be highlighted in order to promote international exchange. The objective is to make the city of Belgrade, Novi Sad, Ni, Kragujevac and their universities attractive to students from all over the world and position them in the global community.

Each university first should evaluate to what extent its activities and efforts have accomplished the goals the institution set (the degree of attainment should be evaluated by itself according to its own goals). In addition, the universities should develop evaluation systems on internalization and the related methodology, procedures, and techniques. Some universities in industrialized countries describe specific evaluation methods including self12

evaluation, peer review, external evaluation, benchmarking, and questionnaire and interview surveys in their international strategies.

CONCLUSION

The internationalization of higher education in Europe is closely related to the politics, economy, culture and society within the region. The Bologna Process represents more than a structural convergence process for higher education systems and frameworks in Europe. Cooperative initiatives throughout the entire region for stimulating the convergence of higher education systems and frameworks must result in future further mobility enhancement.

The wars and their consequences cost Serbia a decade in its EU accession process. Internalization process of higher education must support the Serbias pre-accession process for European Union membership. The setting of a conceptual framework is an integral part of an effective internalization process of higher education in Serbia, as the institutions of higher education will serve as the main promoters to the global educational and research opportunities.

The findings show that the main rationales for internationalization of higher education in transition countries is the recognition of diplomas and degrees abroad, improvement of educational quality, equal partnership on the global level, equal participation of our higher education institutions in the world educational arena (education, research, debates), participation in the development of the global educators' community and better integration into the market economy in a new political and economic environment by learning from the international experience (Djanaeva, 2001).

At the organization level, Serbian HE should be pursuing unique strategies to internationalize with an aim of integrating an international dimension into teaching, research, and service functions of the institutions. Each university must have its own unique international strategy to reflect its individual characteristics and features. Based on it the institutions should carry out the international activities of education and research in a planned manner. Sustained and institutionalized internationalization process is likely to come as a result of intentional and planned change approach. 13

Table 1. Most Important Aspects of Internationalization

Most Important Aspects of Internationalization

Primary Importance

Second level of importance

Third level of importance

1. Mobility of students

3.

Mobility

of

faculty 7. Development of twinning programs

members

2. Strengthening international 4. International dimension in 8. Establishment of branch research collaboration curriculum campuses

5. International development 9. Commercial export/import projects of education programs

6. Joint academic programs

10. Extracurricular activities for international students

Source: adopted from Knight (2003b)

REFERENCES

Abdouli, T. 2008. Higher Education

Internationalization and Quality Assurance

in NorthSouth Cooperation. The International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies. 1 (2): pp. 240-258.

Altbach, P. and Teichler, U. 2001. Internationalisation and Exchanges in a Globalized University. Journal of Studies in International Education. 5 (1): pp. 5-25.

Bashir, S. 2007. Trends in International Trade in Higher Education: Implications and Options for developing Countries. The World Bank Education. Working Paper num. 6. 14

Castells, M. 2001. The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business and Society. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

De Wit, H. 2002. Internationalisation of Higher Education in the United States and Europe. Westport. CT: Greenwood. http://condor.depaul.edu/rrotenbe/aeer/v17n2/Djanaeva.pdf

Djanaeva, N. 2001. The Internationalization of higher education in Kyrgyzstan.

Dooris M. and Lozier G. 1990. Adapting Formal Planning Approaches: The Pennsylvania State University. In Schmidtlein, Frank A., Milton, Toby H. eds. Adapting Strategic Planning to Campus Realities. New Directions for Institutional Research No. 67: pp. 5-21. Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers: San

El-Khawas, E. (1994). Towards a Global University: Status and Outlook in the United States. Higher Education Management 6: pp. 90-98.

Hardy, C. 1991. Configuration and Strategy Making in Universities, Journal of Higher Education, 64, 4: pp. 363-393.

James, R. 2006. An update on the internationalization of Australian universities. http://www.gcn-osaka.jp/project/finalreport/6E/6-4-2e.pdf Keller, G. 1997. Examining What Works in Strategic Planning. In Peterson, Marvin W., et al (Eds.). Planning and Management for a Changing Environment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kishun, R. 2007, The Internationalisation of Higher Education in South Africa: Progress and Challenges in Journal for Studies in Higher Education Vol. 11 No. 3/4: pp. 455-469.

Knight, J. 1999. Internationalization of higher education. In J. Knight, & H. de Wit (Eds.), Quality and internationalization in higher education, Paris: OECD: pp. 13-23.

15

Knight, J. 2003a. Report on Quality Assurance and Recognition Of Qualifications in PostSecondary Education in Canada, OECD/Norway Forum on Trade in Educational Services, Managing the internationalization of post-secondary education.

Knight, J. 2003b. Internationalization of Higher Education Practices and Priorities: 2003 IAU Survey Report. http://www.unesco.org/iau/internationalisation.html

Knight, J. 2004. Internationalization Remodelled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales, Journal of Studies in International Education, 8 (1): pp. 5-31.

Knight, J. 2005. Cross-border Education: Programs and Providers on the Move. CBIE Millennium Research Monograph No. 10. Ottawa: Canadian Bureau for International Education.

Knight, J. 2006. Quality Assurance and Cross-border Education: Complexities and Challenges. http://www.gcn-osaka.jp/project/finalreport/6E/6-2e.pdf

Kondakci, Y., Y.Van den Broecke and H., Devos, G. 2006. More management concepts in the academy: internationalization as an organizational change process. Vlerick Leuven Gent Working Paper Series 2006/28.

Marginson, S. and van der Wende, M. 2007. Globalisation and Higher Education, Education Working Paper No. 8, Paris: OECD.

McCarney, P. 2005. Global Cities, Local Knowledge Creation: Mapping a New Policy Terrain on the Relationship between Universities and Cities. In G. Jones, P. McCarney and M. Skolnik (eds.), Creating Knowledge: Strengthening Nations: The Changing Role of Higher Education, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Ministry of Education and Sport of Republic of Serbia. 2003. Higher Education in Serbia and Bologna Process www.bologna-berlin2003.de/pdf/Serbia.pdf

Bologna Secretariat. 2008. Bologna Process Template for National Reports: 2007-2009. tempus.ac.yu/file_download/68 16

OECD. 2004. Internationalisation and Trade in Higher Education: Opportunities and Challenges, Paris: OECD.

Ota, H. 2006. MEXTs Support Programs for Internationalization of Japanese Universities with a Focus on Strategic Fund for Establishing International Headquarters in Universities http://www.gcn-osaka.jp/project/project-finalreport.htm Pennywell, J. and Chang, Y. 2008. Internationalization of Austin Peay State University: A Strategic Plan for the 21st Century. http://hdl.handle.net/1803/411

Qiang, Z. 2003. Internationalization of higher education: Towards a conceptual framework. Policy Futures in America 1(2): pp. 248-270.

Teichler, U.

2009. Internationalisation of higher education: European experiences, Asia

Pacific Education Review, Springer Netherlands, 10 (1): pp. 93-106.

Van der Wende, M. 2001. Internationalisation Policies: About New Trends and Contrasting Paradigms, Higher Education Policy, 14 (3): pp. 249-259.

Van der Wende, M. 2007. Internationalisation of Higher Education in the OECD countries: Challenges and Opportunities for the Coming Decade. In: Journal on Studies in International Education. Vol. 11, no. 3-4: pp. 274-290.

Van Vught, F.A., Bartelse, J., Bohmert, D., Burquel, N., Divis J., Huisman, J. &. Van der Wende, M. 2005. Institutional profiles. Towards a typology of higher education institutions in Europe. Report to the European Commission.

17

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- University List of UK: Public Affairs DirectorateДокумент6 страницUniversity List of UK: Public Affairs DirectorateMahabub Haider0% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Graduate Employability and Higher Education S Con - 2021 - Journal of HospitalitДокумент11 страницGraduate Employability and Higher Education S Con - 2021 - Journal of HospitalitANDI SETIAWAN [AB]Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- University of Mianwali: Situation VacantДокумент5 страницUniversity of Mianwali: Situation VacantMunnazaОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Compet Exam Result-XII 2022-23Документ17 страницCompet Exam Result-XII 2022-23msnupursinhaОценок пока нет

- Girls Higher Education in Germany in The 1930s PDFДокумент30 страницGirls Higher Education in Germany in The 1930s PDFRachel alexis yimОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Wbneetug MeritlistДокумент297 страницWbneetug MeritlistAa BОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- IELTS Writing Test With ExamplesДокумент27 страницIELTS Writing Test With ExamplesBonifacius RhyanОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Person Specification: Job Title: Events CoordinatorДокумент2 страницыPerson Specification: Job Title: Events CoordinatorC MОценок пока нет

- ExamДокумент6 страницExamJovertОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Stedro Asat23novДокумент63 страницыStedro Asat23novOnyekachi JackОценок пока нет

- "A Quality Function Deployment QFD Approach in Determining The Employer's Selection in KAMCO" 1Документ23 страницы"A Quality Function Deployment QFD Approach in Determining The Employer's Selection in KAMCO" 1International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Education Should Be FreeДокумент6 страницEducation Should Be Freefebty kuswantiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Edexcel SyllabusДокумент246 страницEdexcel SyllabusPavan SoniОценок пока нет

- University of Alberta Calendar 2021-2022 University of AlbertaДокумент2 страницыUniversity of Alberta Calendar 2021-2022 University of Albertapranv tezОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Final InstwiseadmДокумент311 страницFinal InstwiseadmWhite WolfОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Wbjee 2024Документ1 страницаWbjee 2024SHOUNAK BERAОценок пока нет

- Judgement 29019-2015 Hugh Court Judgement For Kerala Medical Council Dispute For Tbilisi Medical UniversityДокумент11 страницJudgement 29019-2015 Hugh Court Judgement For Kerala Medical Council Dispute For Tbilisi Medical UniversityYukti Belwal100% (1)

- Journal of Baltic Science Education, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2018Документ181 страницаJournal of Baltic Science Education, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2018Scientia Socialis, Ltd.Оценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- NucДокумент24 страницыNucOgunyinka, Emmanuel KayodeОценок пока нет

- Fakir Mohan UniversityДокумент5 страницFakir Mohan UniversityhareshОценок пока нет

- PR FinalДокумент14 страницPR FinalJieza May MarquezОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Final Internship Report of ComsatsДокумент49 страницFinal Internship Report of ComsatsMuhammad Umair100% (1)

- Philippine EducationДокумент12 страницPhilippine EducationChrystel Jade Balisacan SegundoОценок пока нет

- Provisional Merit List Publish 1st Round 03.08.2023Документ22 страницыProvisional Merit List Publish 1st Round 03.08.2023Sourav SahuОценок пока нет

- Question ID: Topic Name:Mathematics-Section AДокумент31 страницаQuestion ID: Topic Name:Mathematics-Section Alakshay bhardwajОценок пока нет

- JAM 2016 Joint Admission Test For M.Sc. 2016: Indian Institute of Technology Madras, ChennaiДокумент1 страницаJAM 2016 Joint Admission Test For M.Sc. 2016: Indian Institute of Technology Madras, ChennaiAnurag KumarОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Collaborative Desktop Publishing Results Calamba CityДокумент5 страницCollaborative Desktop Publishing Results Calamba CitySammy Figura GrubanzoОценок пока нет

- ApplicationsdgshteryДокумент7 страницApplicationsdgshterygmik02Оценок пока нет

- MNGT220 Week 5 Tutorial 3: - Strategic Positioning - The Environment - PESTEL Framework - The 5 Forces FrameworkДокумент14 страницMNGT220 Week 5 Tutorial 3: - Strategic Positioning - The Environment - PESTEL Framework - The 5 Forces FrameworkSayan BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- DAAD-Scholarship BookДокумент2 страницыDAAD-Scholarship BookHarsh GoswamiОценок пока нет