Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Public Perception of Science and Technology in A Periphery Society: A Critical Analysis From A Quantitative Perspective - Vaccarezza

Загружено:

Can BayraktarИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Public Perception of Science and Technology in A Periphery Society: A Critical Analysis From A Quantitative Perspective - Vaccarezza

Загружено:

Can BayraktarАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Science Technology & Society http://sts.sagepub.

com/

The Public Perception of Science and Technology in a Periphery Society: A Critical Analysis from a Quantitative Perspective

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza Science Technology Society 2007 12: 141 DOI: 10.1177/097172180601200107 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sts.sagepub.com/content/12/1/141

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Science Technology & Society can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sts.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sts.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://sts.sagepub.com/content/12/1/141.refs.html

>> Version of Record - May 11, 2007 What is This?

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

141

The Public Perception of Science and Technology in a Periphery Society: A Critical Analysis from a Quantitative Perspective

LEONARDO SILVIO VACCAREZZA

In this article a series of variables referred to the general publics valuations of science and technology are analysed. These valuations refer to different dimensions of science and technologyas a utility of scientific knowledge, their legitimacy, their bond with the cultural matrix of everyday life. The analysis is based on information from a survey carried out in a great urban conglomerate of a little scientific developing country, Argentina. We see that valuation variables discriminate the public according to their positive or negative responses about science, but that there is no evident association between them. We consider one variable in particular dividing the public into those who are trustful and those who are cautious regarding the advances of science, and we see how it is related to other significations of valuation. The pre-eminence of positions of ambivalence or contradiction in the populations perception regarding this topic is discussed. A factor analysis is presented that comprises these variables and that presents a set of valuation orientations towards science as a result. Finally, it is interesting to see how education and the level of understanding of scientific knowledge affect the publics valuation, which questions the basic supposition of the tradition of public understanding studies.

THERE HAS BEEN a significant development in studies on the public perception of science and technology in advanced countries in the last fifteen years, motivated by different interests: political, cognitive, educational, professional and even commercial. This has given risen to a set of perspectives that, although contradictory in many aspects, are all concerned

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza is Researcher, Instituto de Estudios Sociales de la Ciencia y la Tecnologa, Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Argentina. E-mail: leonvaca@unq.edu.ar. Science, Technology & Society 12:1 (2007) SAGE PUBLICATIONS LOS ANGELES/LONDON/NEW DELHI/SINGAPORE DOI: 10.1177/097172180601200107

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

142

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

about the relation of non-experts with the expert knowledge produced in the institutionalised framework of science and technology. Thus, those who focus this question on scientific literacy as a function of scientific education in educational institutions deal with the question of what to teach and with what objectives (Fourez 1997; Shamos 1995) within the concept of good citizen (Lee and Roth 2003). From another perspective, the concept of public understanding of science (PUS) established by the tradition of national surveys to measure the publics level of understanding of scientific knowledge, interest in scientific issues, and attitudes referred to science and technology goes about this question not only in order to help overcome the increasing gap between science and the public (Bensaude-Vincent 2001) for a higher participation of the individual in the contemporary world, but also in order to strengthen the social legitimacy of science. The studies that criticise the PUS perspectives aim to question the implicit superiority of science on technical decisions with social consequences, and, specially, on the consideration of the technological risk. From a perspective directly influenced by the social studies on science, the objective is to analyse science just as common sense knowledge is analysed, to articulate its construction with the local senses in which science is produced, which is influenced by the cultural contents of the society where science is constructed. The attention on the nonexperts knowledge based on experience and on the signification given by them to expert knowledge in local processes of negotiation of technical decisions opened a new promising grounds for studies on the relation between the understanding of science and technology by lay people and the social use of expert knowledge (Collins and Evans 2002; Irwing 2001; Wynne 1995; Yearley 2000). These lines of inquiry have been consolidated in empirical studies, which in general have been carried out in developed contexts, that is local or national environments in which science is produced. This means there is a dense framework of relations of knowledge (Dagnino and Thomas 1999) among several types of social actors, and proximity between the responsible experts and lay users, which implies, in the case of the latter, a clearer awareness that scientific and technological knowledge is the product of their own society. It is not possible to discard that the social perception of science and technology within non-developed contexts should be influenced by an effect of absence of local scientific and technological production. In developed countries the relation between the core set of technological decisions with public effect and the user public is

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

143

closer (as identification of the institutional sites where those decisions are taken and as recognition of scientists and technicians involved), so the relation between qualified experts and the experience of non-experts (Collins and Evans 2002) finds a more structured social space. On the other hand it could be stated that the social perception of scientific knowledge as a cultural product and of science as an institution of modern society is a component of the globalised culture, spread through internationalised mass media and through uniform technologies, not much affected by hybridisation processes in local situations. Thus, the public perception of science will not be presenting significant differences between central and periphery countries with intermediate development, which are similarly subject to the use of international technology and to the discourses involved in public controversies about the activities and impacts of science and technology. In spite of the different perspectives of analysis, it can be said that the studies on the public perception of science and technology constitute a field of not stable knowledge types, with important theoretical gaps and inaccuracies, and with widely recognised methodological weaknesses. Apart from the dispersion of topics and conceptual frameworks, we should also mention the question of universal and local knowledge on this matter in other words, the differences of this phenomenon between social contexts that are clearly divergent in terms of the centreperiphery dimension. Thus, there is a new field of inquiry in which uncertainties are higher. In this work we will not go along this line that requires a comparative strategy. In turn, we will analyse some indicators of valuation made by the public about science and technology in a context of their lower institutionalisation, compared to the situation in central developed contexts. By doing so, we think we may be contributing to broadening the scope on this topic by making an analysis corresponding to a context that is not often investigated by specialised research. The analysis presented is based on information from a survey carried out in the urban conglomerate of Greater Buenos Aires, which applies some internationally used indicators.1 These quantitative studies have been criticised for the lack of subtlety of the indicators to identify its significations among respondents (Davison et al. 1997; Michael 2002; Wynne 1995). It should be taken into account that the surveys carried out by national or supranational entities of scientific policy have paid attention to three types of PUS components: knowledge, attentiveness and attitudes (Miller et al. 1998). The definition of these general concepts, as well as the sub-dimensions they consist of and the indicators formulated

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

144

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

to measure these concepts show important weaknesses. The indicators of knowledge are, then, only a set of scientific affirmations that are certified and codified (some are currently controversial), and the understanding of the scientific method is a strictly Popperian version, which neither guarantees the pretensions found in the idea of scientific literacy regarding the communication of the scientific mentality (Davis, quoted by Shamos 1995), nor the claim that lay peoples knowledge of science and technology can be considered for its utilisation (Fourez 1997). The idea of attentiveness refers to the self-valuation of the surveyed agent, subject to a simple scale of categories (very, moderate, not at all), whose significations granted by the agent are unknown and, therefore, this makes it impossible to compare these terms in the whole sample. Last, the attitudes are used without a clear theoretical orientation of what that concept means. They can be considered fixed devices in the subjects dispositions that are activated by a certain prompt (a question or exposition to a valuation phrase) to generate a conduct (response, measured by the Lickert scale). This poses two kinds of doubts: on the one hand, as in the case of the concept of attentiveness, the pretended homogeneity in the meaning subjects give to the prompts. On the other hand the validity or utility of such device to characterise valuation concepts of the subject, which is constructed in ever-changing scenes of interaction. In this regard, the attitudes derived from the behavioural tradition may be interpreted as a component of concepts like that of social representation (Moscovici and Morkov 1998), understood as a continuous construction in processes of interaction, so that it is difficult to say that attitudes keep their subjective significations unchanged. For all that has been said, the quantitative approach is very rustic in the analysis. Even so, it is legitimate to use it so long as the statistical outputs are carefully interpreted, that is we try to avoid considering the agents responses to valuation prompts as a fixed and constitutive attitude of the subject. These responses are, instead, expressed in the fleeting scene of interviews in a context of signification comprising different aspects: the historical moment full of events that affect the meaning of responses, and also the immediate context of the questionnaire and the different prompts ordered to get the subjectivity of the respondents. This makes results (the positive and negative responses in terms of appreciation of science and technology) somewhat provisory, and this should be taken into careful account when interpreting the data. On the other hand the surveys on this topic are increasingly more present in the field of scientific and technological policy, and this cannot be overlooked. All governments

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

145

have been incorporating them in their public agendas, thus following the classic path of institutional isomorphism. As such, they are instruments of power, which requires paying more attention to their use, not in order to indicate inherent conceptual and methodological weaknesses, but in order to explore the deviation and contradictions so as to generate new interpretative frameworks of the public perception of science and technology. In this work we will analyse a series of variables referred to the respondents valuations of science and technology. These valuations make reference to different dimensions of judgement on science and technology, for example, the utility of scientific knowledge, their legitimacy, their bond with the cultural matrix of everyday life. We will see that these variables divide the public according to their positive or negative responses about science, but that there is not an evident association between them. We will consider one variable in particular, classifying the public between those who are trustful and those who are cautious regarding the advance of sciences, and we will see how it is related to other significations of valuation. We will discuss if this indicates the pre-eminence of positions of ambivalence or contradiction, and we will try to formulate some hypotheses to this respect. Then we will present a factor analysis that comprises these variables and that presents a set of valuation orientations towards science as a result, and we will discuss the interpretative value of this tool in the context of the analysis. Third, we are interested in showing how educational level and the level of understanding of scientific knowledge affect the publics valuation, which will question the basic supposition of the tradition of PUS studies.

Trustful and Cautious

One question from the questionnaire formulated as Many people think that science development brings about problems to humanity. Do you think this is true? shows us two different categories depending on whether the answer is in the affirmative or negative. The first ones are referred to as cautious towards science, and those who are not afraid of its development as trustful. The sample was divided almost in halves between both options: 141 cases for the first and 145 for the second. Respondents had to justify their answer. The question was made after a set of Lickert scale prompts about valuations of science and technology that could be both

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

146

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

positive and negative, and after a set of statements on scientific knowledge that the respondent must consider as true or false. Once the question is taken into account along with the previous questions, it cannot be said that they have systematically conditioned the understanding of the prompts or the response. Of course, we did not have any argument to ensure a homogeneous meaning in the surveyed population;2 however, from a syntactic and semantic point of view, the question was made in a colloquial way and did not seem to lead to mistakes or to an interpretation bias. It may be argued that the fact of presenting the topic as an affirmative statement held by many people might have led to affirmative responses to the question. But the colloquial nature of the expression only stresses the importance of the affirmation rather than suggesting a net preference of the public. The dichotomous response to the question does not bear any statistical association with the valuations of science (or of science and technology) that are expressed through other prompts. In fact, the questionnaire included a set of affirmations of the agreementdisagreement type that made reference to different aspects: the utility of science or scientific research, the legitimacy of scientific knowledge as a cultural basis of society, the integration or strangeness of science regarding ordinary peoples everyday life, scientific knowledge as a source of risks to life, the valuation of scientific activity and of scientists as professionals. Some of these indicators were worded as positive statements towards science and others as affirmations with a negative meaning. Some of them gave responses that were focused on either of the values (agreement or disagreement) and others made a more equal discrimination. In Table 1 it is possible to see valuation indicators, showing the percentage of responses that are favourable to science and technology (whether as an agreement or disagreement response depending on the meaning with which the statement was made) for the total sample and for the group of cautious and trustful. Science and technology are highly appreciated since for 74.7 per cent of the sample it is the main cause for improvement in quality of life; it is expected to cure diseases like AIDS or cancer (92.7 per cent); its benefits are more than the prejudices it can arouse (72 per cent); science is the best resource of accurate knowledge about the world (67.8 per cent); and it prevents us from becoming an irrational society (60.7 per cent). Whats more, 58.3 per cent of the respondents think that science promises solutions but fails to fulfill the same. However, this positive valuation of science is not universal: for example, only a minority of 42.6 per cent think

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

147

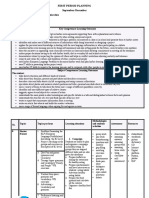

TABLE 1 Percentage of Opinions Favourable to Science and Technology Gamma Cautious Trustful Total coefficient

Prompts The main cause of the improvement in human life quality is the advance of science and technology The progress of ST will help cure diseases like AIDS, cancer, etc. The application of ST will increase work opportunities Science and technology can solve all problems Science seems to promise the solution to all evils, but in the end these promises remain unfulfilled* The benefits of science are more than the prejudices Science is the best accurate knowledge resource about the world If we neglect science, our society will be increasingly more irrational The world of science cannot be understood by ordinary people* Over time science will make it possible to understand all that happens If scientists were in charge of government policy, things would be better We attribute too much truth to science and little truth to religious faith* Science and technology do not care for the problems of the people* Science changes our way of life very quickly* There are too many issues related to ST on which not even scientists themselves can agree, and it is difficult to know if they are good or bad for humanity* ST are out of control and there is nothing we can do to stop that*

68.8 91.3 31.9 11.8

80.6 94.2 54.7 16.0

74.7 92.7 42.6 13.4

0.260 0.115 0.391 0.234

50.0 63.8 63.8 57.5 34.1 36.3 35.5 39.1 61.6 29.1

68.4 79.9 71.9 65.8 44.6 48.7 36.0 44.6 67.6 40.0

58.3 72.0 67.8 60.7 39.1 41.7 36.0 41.9 64.4 33.7

0.322 0.219 0.166 0.040 0.210 0.221 0.054 0.135 0.130 0.271

14.9 63.2

31.0 75.3

23.0 68.3

0.395 0.291

Note: *Indication of the percentage of disagreement with the statement.

the application of science and technology will increase work opportunities, while only 41.7 per cent think that over time science will enable us to understand all that happens. At the same time just 13.4 per cent dare to support the idea that science and technology can solve all problems. Most people also reject the idea of scientists charge of government

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

148

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

(only a third consider it convenient). Thus, the enthusiasm for science and technology finds its limitations in the achievement of sciences, but also in other negative valuations: 57.3 per cent of the respondents think we attribute too much truth to science and little to religious faith; 57.9 per cent think science changes our way of life very quickly; for 60.5 per cent it cannot be understood by ordinary people; and 66.2 per cent feel that there are too many issues related to ST on which not even scientists themselves can agree, and it is difficult to know if they are good or bad for humanity. Thus, it can be said that most people surveyed have expectations and a favourable valuation of science and technology, that the valuation does not lead them to have exaggerated expectationsor, in other words, that they recognise there are limits to the benefits deriving from science and technologyand that, although they do not think they advance without any control, they do so without considering other sources of knowledge like, for example, religious or the concern for keeping traditional values intact. In this regard, ordinary people tend to see science as a strange force, which is beneficial yet incomprehensible and at times turbulent. As it can be seen from Table 1, the values are relatively independent from whether respondents feel either precaution or trust. Although in all cases the positive valuation of science is higher among the trustful ones than among the cautious, the percentage differences between them and the association coefficients show there is proximity in their attitudes. For example, in spite of having the opinion that science brings about problems to humanity, 68.8 per cent of the cautious respondents consider it the main cause of the improvement in quality of life, nine of ten hope it can cure current serious diseases, almost 64 per cent think science is the best resource of knowledge and that its benefits are more than prejudices, for 57.5 per cent science is a guarantee against an irrational society, and 63.2 per cent consider its development does not represent any danger of its becoming uncontrollable. In these cases the percentage difference with trustful respondents does not exceed 16 per cent. And even among these, despite their more positive orientation towards science, many of them have a critical point of view: more than 80 per cent of the trustful ones do not believe it can solve all the problems of humanity; less than half expect that science will allow them to know all that happens in the world; 55 per cent seem to regret that science is so highly appreciated to the detriment of religious faith; 58 per cent are afraid that science and technology may change our way of life very quickly; 62 per cent think

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

149

the uncertainty about the advances of science and technology is due to scientists unresolved controversies; and, moreover, scientists are not considered to be the governmental ideal (56 per cent). In general, the coefficients of association show that there is independence between the trustful or cautious orientation and the indicators of valuation. In the case of higher coefficients, both groups concentrate their cases on the same positive or negative value of the indicator. The highest coefficient of association can be seen between the prevention trust attribute and the perception that scientific controversies give rise to uncertainties regarding the consequences of the development of science and technology (gamma = 0.395). This indicator brings up a core affirmation of the concept of risk society developed by Beck (1992), according to which a reflexive society faces the uncertainty caused, especially in the scope of environment, by the application of scientific and technological results, undermining the trust in science. The fact that the coefficient of association is low (even if it is the highest in the series) indicates that the publics concern for the lack of consensus in science is a significant dimension of reflexive modernity.3 In fact, the cautious seem uncertain about the advance of science of scientific controversies (only 14.9 per cent refute the statement about the lack of agreement between scientists as a source of uncertainty on the benefit of science for humanity). Nevertheless, among the trustful also a low proportion refute the same statement (31 per cent), that is, those who do not tend to think that science can cause problems to humanity. Even among those who trust science, most perceive a shadow of insecurity cast by the advance of knowledge. As we have seen, for 70.5 per cent of the total sample the world of science cannot be understood by ordinary people. The difficulty for lay people to understand scientific content does not help configure the image that science neglects the problems of people. In fact, 61 per cent of those who consider that science is an entity cognitively isolated from everyday life reject the affirmation that science does not care for the problems of people (the percentage for the total sample is 64.4 per cent). This leads us to an important concept: the distinction between esoterism and responsibility, which suggests that, as an expert system (Giddens 1990), far from the experience of real life, it nonetheless fulfils a responsible function in society. The distinction between lay peoples alienation of understanding and the responsible function of science becomes evident when related to another indicator of valuation: those who believe that people who cannot understand science mostly think (64 per cent) that if science

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

150

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

were neglected, we would succumb to irrationality. In this sense, not only does science care, according to the perception of the public, for the problems of people, but it also constitutes the cultural matrix essential to maintaining a rational lifestyle of modernity.

Evaluative Ambivalence or Complexity of Science and Technology

Just as we can see that the two orientations of precaution and trust towards science are not associated with the values that could be considered equivalent to other indicators of valuation, there are no significant associations among these. As we can see in the matrix in Table 2, the gamma coefficient of association only gets above 0.4 in a few relations. But even the highest of thembetween the opinion that the benefits of science are higher than the prejudices, and that science is the best resource of true knowledge (0.503)we find a high number of respondents that contradict this association: almost 50 per cent of those who think that science does not ensure more benefits than prejudices believe that even so it is the best resource of knowledge, and almost 60 per cent of those who do not agree with this preference of science maintain that its benefits are higher than the effects arising from prejudice. This distribution model with high percentages of deviations from the main diagonal of the expected association among indicators of valuation can be seen in all the variable crosses, indicating a strong ambivalence as to the meaning of science and technology for the public. There can be different explanations for the publics valuation ambivalence4 on science. According to a first hypothesis, the different indicators could reflect different prevailing values in society. Since values do not set perfectly compatible borders among them, but rather ambiguous significations in their applications, social agents tend to have preferences that are mutually incompatible. For instance, Lujn and Todt (2000) have found responses in which ethical values overlap with utility values regarding applications in biotechnology. The second hypothesis does not stress the ambiguity of valuations by the agent, but the complexity of the object of value. According to this, the discourse on science and technology would refer to a complex and extended object in such a way that each of the indicators built covers a segment of the objects signification. Considering that science brings about problems to humanity does not take its negativity to science by

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

TABLE 2 Matrix of Correlation between Valuation Indicators (gamma) 6 0.43 0.383 0.44 0.317 0.15 0.202 0.208 0.149 0.172 0.079 0.503 0.391 1 0.469 1 0.32 0.12 0.02 0.256 0.375 0.27 0.17 0.159 1 0.363 0.185 0.289 0.45 0.136 0.278 0.305 0.316 0.169 1 0.24 0.16 0.25 0.311 0.156 0.31 0.26 0.221 0.13 0.072 1 0.02 0.07 0.095 0.077 0.149 0.16 0.22 0.124 0.066 0.164 0.04 0.01 0.135 0.116 0.331 0.149 0.02 0.241 0.207 0.32 0.1 0.305 0.278 0.312 0.448 0.13 0 0.046 0.135 0.142 0.02 0.15 0.021 0.07 0.064 0.058 0.012 0.096 0.05 0.003 0.15 0.13 0.132 0.101 0.195 0.065 0.022 0.047 0.107 0.045 0.04 0.11 0.009 0.053 0.017 1 0.11 0.136 0.102 0.145 1 0.17 0.166 0.226 1 0.239 0.292 1 0.059 1 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

0.48 1

0.38 0.12 1

0.089 0.103 0.41 0.13 0.208 0.42 0.267 0.014 0.25 1 0.034 0.14 1 0.271 1

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

151

Notes: 1. The main cause of the improvement in life quality is the advance of science and technology. 2. The progress of ST will help cure diseases like AIDS, cancer, etc. 3. The application of ST will increase work opportunities. 4. Science and technology can solve all problems. 5. Science seems to promise the solution to all evils, but in the end these promises remain unfulfilled. 6. The benefits of science are more than the prejudices. 7. Science is the best accurate knowledge resource about the world. 8. If we neglect science, our society will be increasingly more irrational. 9. The world of science cannot be understood by ordinary people. 10. Over time science will make it possible to understand all that happens. 11. If scientists were in charge of the government policy, things would be better. 12. We attribute too much truth to science and little truth to religious faith. 13. Science and technology do not care for the problems of people. 14. Science changes our way of life very quickly. 15. There are too many issues related to ST on which not even scientists themselves can agree, and it is difficult to know if they are good or bad for humanity. 16. ST are out of control and there is nothing we can do to stop that.

152

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

inducing the opinion that it is not the main means of knowledge. This means that the public thinks of science as a polyhedron that may give rise to different attitudes in the same person. Third, we could support the idea that the question of science and technologymainly the firstis not a topic of exchange and social signification in everyday life. Thus, the public should not be expected to build stable and integrated significations about it on a common or socialised background of knowledge (Alfred Schtz), so that coherent and mutually exclusive ideological schemes referred to this issue could be integrated. Last, should we accept the concept of reflexive modernity, then the relationship of the public with science and technology is full of ambiguity. On the one hand science has gained ground as the base for technological solutions to societys problems and its significations have gradually moved further away from common sense (Bensaude-Vincent 2001), making expert systems act as legitimate mediators of the gap between social experience of the problem and solution (output), reducing the agents autonomy when faced with the impositions of techno-science (Giddens 1990). On the other hand the reflexivity of society regarding science and technology is presented as the perception of consequences that are undesired and unforeseen by these (Beck 1999), which questions the trust and legitimacy in these institutions. In the same sense, the ambiguity of attitudes towards science and technology can be interpreted as a consequence of technoscience phenomenon. Ziman (2000; 2003) says that the public sees a base of trust in non-instrumental science (academic science), but technoscience (science colonised by technology and utility) corrupts the cultural sense of science, and its relation with society and the public (the civil society). It could be said that the publics ambiguity derives from its perception of the tension between non-instrumental academic science and techno-science. The four hypotheses presented about the ambiguity in the publics responses to the indicators of valuation of science and technology5 are not incompatible with one another. In particular, the fourth hypothesis stresses the distance of scientific knowledge from common sense and everyday life, as does the third hypothesis, but the difference is that the latter makes more emphasis on the attitude of fear and the perception of technological risk. It can also be stated that the process of late modernisation of reflexive modernity has an influence on the valuation integration of society and makes the agents preferences more scattered. At the same time the growing complexity of science and technologyas a body of knowledge,

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

153

institutions, practices and professional types involvedgives rise to more aspects or dimensions of science and technology for the valuation scrutiny of lay people. However, we will not go deeper into the empirical analysis of these hypotheses as long as the source of information available does not make it possible, these being left as plausible explanations for further studies.

Factor Analysis

For a set of eighteen indicators of valuation of science and technology6 a varimax factor analysis was carried out, the maximum adjustment resulting in four factors (Table 3). A first factor, which we called adherence to science and technology encompasses a series of strongly affirmative indicators of the value of science, specially in terms of the utility of knowledge (the benefits of science are more than the prejudices, the main cause of the improvement in life quality is the advance of science and technology, the progress of science and technology will help cure diseases like AIDS and cancer, and the application of ST will increase work opportunities), and of science as an essential component of culture (science is the best resource of accurate knowledge, and if we neglect science, our society will be increasingly more irrational). The perception that science cannot be understood by lay people is added to this factor with a relatively low value. Both in relation to the question of utility and to the validity of scientific knowledge as a basis of culture, this affirmation is not incompatible with the hypothesis that was discussed regarding the growing gap within the public between science and its valuation as reliable expert knowledge. A second factorwhich we called criticism to science and technology shows indicators of negative valuation or which play down the value of science. First, an expression of insecurity in knowledge due to the lack of agreement among scientists, and the perception that science often fails to fulfil the expectations people have of it. There is also the conviction that science brings about problems to humanity, and that science and technology do not address the problems of people, although this indicator shows a lower coefficient. In general, the factor represents an attitude that questions scientific and technological activity, not because of their own value, but because of the failure to fulfil promises and an adequate orientation to meet the problems of humanity.

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

TABLE 3 Factor Analysis Based on Variables of Valuation of Science and Technology 1 0.720 0.699 0.683 0.589 0.573 0.504 0.461 0.380 0.307 0.710 0.695 0.515 0.477 2 3 4

Indicators of valuation of science and technology

154 Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

The benefits of science are more than the prejudices The main cause in the improvement of life quality is the advance of ST Science is the best resource of accurate knowledge about the world If we neglect science, our society will become increasingly more irrational The progress of ST will help cure diseases like AIDS, cancer, etc. The world of science cannot be understood by ordinary people The application of ST will increase work opportunities There are too many ST issues on which not even scientists can agree, and it is difficult to know if they are good or bad for humanity Science promises the solution to all evils, but in the end these promises remain unfulfilled The development of science brings about problems to humanity Science and technology do not care for the problems of people Science and technology can solve all problems Scientific knowledge improves peoples ability to decide important things If the government policy were in charge of scientists, things would be better Over time, science will make it possible to understand all that happens We attribute too much truth to science and little truth to religious faith Science changes our way of life very quickly ST are out of control and there is nothing we can do to stop that 0.431

0.726 0.703 0.597 0.526

0.364 0.674 0.610 0.589

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

155

The third factornave optimismis shown by a set of valuations towards science that seem exaggerated, and this is expressed in different aspects. First, it is expressed through the efficacy of science to solve all problems or to understand all that happens around the world. Second, by its value as a means or instrument for the individual to manage life. Third, by means of the trust in scientific knowledge to be used as government of the state. The factor indicators consist of taking the expectations people have of science and technology to an extreme. Unlike the first factor, which evaluates both in comparative terms (it is the best resource of knowledge, it has more benefits than prejudices, it is the main cause of life quality), the third factor evaluates them in absolute terms (it will solve all the problems, it will understand all that happens) and establishes a direct relation between science and agency (it will enable me to take the important decisions, it ensures a good government). The last factorconservative oppositionoutlines a negative orientation mainly based on the rejection of science and technology, and on the fear of its consequences (it changes our way of life too quickly, or it is out of control). This negativity is supported from a system of different knowledge: religious faith. Unlike the second factor, in which the negativity was based on the inefficacy or disorientation of science to fulfil its progress function, in this case science is rejected because it goes against established life. The coefficients of the components in each factor that conceptually define it are high and significantly low in the other factors; consequently, the correlation among factors is low or non-existent. This enables us to underpin the plausibility of the interpretative concepts that were elaborated. We can see that, in general, in the correlation matrix presented earlier, the components associated with each factor have relatively high association coefficients among them (although they are always lower than gamma = 0.500). However, the covariance is not high enough to discard the existence of several cases deviating from its direction, which makes it impossible to configure the sample according to the four factors detected and to define social groups adjusted to the four orientations described. From a theoretical interpretation of the factor analysis, it could be stated that it enables to make a description of culture but not of society. In fact, it enables us to describe the valuation orientations or the significations allocated to science and technology by the public, but it does not allow us to group the members of the sample into differentiated parties. Instead, we can conclude by interpreting that the four orientations are

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

156

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

present to variable degrees in the set of individuals the surveyed public consists of. Once again, this reinforces the idea of the ambiguity previously discussed.

Valuation and Educational Level

The affirmation of educational level affecting the ability to understand scientific and technological knowledge, which in turn affects the positive valuation of science, has been established as an axiom of studies on public understanding of science based on general surveys. The first part of the affirmation is stressed by the values shown in Table 4, according to which the highest understanding of scientific knowledge is 10.5 per cent at the primary education level up to 75.6 per cent at the complete university level. Regarding the second partthe relation between the understanding of scientific knowledge and the different valuation indicators of science and technologyhowever, the data do not appear to be in accordance with it. This is clearly shown in the table.

TABLE 4 Level of Understanding of Scientific Knowledge According to Educational Level (%) Index of understanding 0 to 3 4 to 6 7 to 8 Educational level IT CT 5.3 47.4 47.4 100.1 7.7 53.8 38.5 100.0

P 47.4 42.1 10.5 100.0

IS 17.3 63.5 19.2 100.0

CS

IU 6.4 38.5 55.1 100.0

CU 2.4 22.0 75.6 100.0

11.3 64.5 24.2 100.0

Notes: P: complete primary school; IS and CS: incomplete and complete secondary education; IT and CT: incomplete and complete tertiary education; IU and CU: incomplete and complete university education.

Although the association coefficients between the levels of understanding and the evaluation indicators are low, some of them describe systematic variations depending on understanding. For example, the opinion that science is incomprehensible for ordinary people decreases, as is expected, as the level of knowledge increases. Although the majority of the people that are most informed about science think that science and technology are the main cause of the improvement in humanitys life quality, this affirmation is less frequent among them than among the less

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

157

qualified agents. The perception that the benefits of science are more than the prejudices also decreases as knowledge increases, or that science is the best resource of accurate knowledge, as well as the maybe nave valuation that over time science will enable us to understand everything, or that scientific knowledge enhances our ability to take important decisions. A more negative datum is presented by the favourable expectation of a government managed by scientists, which goes from 63.6 per cent among the less qualified to 27.6 per cent among the most informed respondents. Among those that have more scientific information, the perception that the development of science brings about problems to humanity is higher (only 27.8 per cent do not agree with this). This group of indicators reveals a more relative attitude towards science and technology among the most informed share of the population, and the same trends can be observed should the independent variable be educational level (see Table 5). On the one hand these data question the axiomatic affirmation that links knowledge of science to valuation. On the contrary, the most informed public seems to question the intrinsic goodness of scientific and technological advance. This can be clearly seen in the indicators contributing to the factor we called nave optimism (the government managed by scientists, the virtue of science to understand it all, or that science improves our ability to take important everyday decisions). However, on the other hand, the higher the level of understanding of scientific knowledge, the higher the acceptance of scientific activity as an effort made by society: for example, the higher the level, the higher the recognition that science cares for the problems of people; the lower the acceptance of the opinion that science and technology offer false promises, the higher the rejection that science is out of control. In this sense the level of understanding of the cognitive content of science and technology (and educational level) reinforces the support to science from a critical point of view and discredits the exaggerated adherence to a nave optimism. The indicator development of science brings about problems to humanity enabled us in a previous section to distinguish two groups: those that are trustful and those that are cautious of science and technology. We observed that the level of understanding of scientific knowledge has a negative influence on the share of trustful respondents. As regards educational level, relation is not so clear (Table 6).

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

TABLE 5 Positive Responses to Indicators of Valuation of ST According to Levels of Understanding of Scientific Knowledge (%)

Indicators of valuation of ST 81.8 90.9 63.6 81.8 63.6 36.4 0.0 36.4 72.7 45.5 27.3 100.0 27.3 63.6 27.3 18.2 47.8 54.5 54.5 50.0 40.9 54.5 95.5 13.6 68.2 72.7 9.1 51.1 31.8 22.7 34.1 73.2 46.3 48.8 56.1 87.8 51.2 65.9 75.6 12.2 44.4 19.5 81.8 72.7 72.7 63.6 63.6 73.2 78.0 68.3 22.0 75.6 68.2 54.5 68.2 27.3 81.8 40.9 81.8 27.3 45.5 40.9 95.5 45.5 54.5 86.4 13.6 27.8 22.7 63.6 61.0 50.0

Understanding level score 1 and 2 3 and 4 5 and 6 7 and 8 Total 61.5 76.0 69.8 70.8 37.5 69.8 29.2 66.7 45.8 45.8 49.0 92.7 38.5 63.5 71.9 12.5 42.0 27.1

Gamma 0.264

158 Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

0.423 0.466 0.368 0.042 0.025 0.192 0.359 0.126 0.480 0.004 0.584 0.197

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

The world of science cannot be understood by ordinary people The main cause of the improvement of life quality is the advance of science and technology The benefits of science are more than the prejudices Science is the best resource of accurate knowledge about the world If government policy were in charge of scientists, things would be better Science and technology do not care for the problems of people There are issues on which scientists do not agree, and it is difficult to know if they are good or bad for humanity Science promises the solution to all evils, but in the end these promises remain unfulfilled Over time science will make it possible to understand all that happens We attribute too much truth to science and little truth to religious faith The application of ST will increase work opportunities The progress of ST will help cure diseases like AIDS, cancer, etc. Science changes our way of life too quickly If we neglect science, our society will become increasingly more irrational ST are out of control and there is nothing we can do to stop them Science and technology can solve all problems The development of science brings about problems to humanity (percentage of trustful ones ) Scientific knowledge improves peoples ability to decide important things

0.298 0.133 0.136 0.477 0.426

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

159

TABLE 6 Distribution of Trustful and Cautious Respondents Regarding Science and Technology According to Educational Level (%) Educational level (grouped) I Trustful Cautious 42.3 57.7 II 58.0 42.0 III 46.9 53.1 Total 48.8 51.2

Notes: I. complete primary and incomplete secondary education; II. complete secondary and incomplete tertiary education; III. complete tertiary and complete and incomplete university education.

The gamma association coefficient between educational level and those trustful or cautious of science and technology is 0.018, while for the relation between the level of understanding of scientific knowledge and the same dependent variable its value is 0.584 (see Table 5). Consequently, educational level does not affect the orientation of prevention from or trust in science, but this does happen in the case of the level of the agents scientific information. Social attitudes and representations are built in environments of interactions (Moscovici and Morkov 1998). The construction of significations of science and technologyand among them the valuation and expectationsis built and prevails through systems of interaction in which it is especially significant to see how scientific knowledge is created and utilised. An environment of interaction in which this is relevant is university. We have observed that among respondents with incomplete university education, those who attend university show a predominance of cautious towards science, while those who do not attend university are predominantly trustful (Table 7).7

Table 7 Distribution of Trustful and Cautious Respondents with Incomplete University Education, According to Whether They Attend University Attend university Orientation towards science Trustful Cautious Total Gamma = 0.439. Yes 37.5 62.5 100.0 No 60.6 39.4 100.0 Total 47.1 52.1 100.0

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

160

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

The environment of interactionin this case, universityis a resource to explain the association of the indicator trustfulcautious with the level of understanding of scientific knowledge. Indeed, going to university nowadays is a stimulus to maintain the recall of scientific content. Literature has pointed out the effect of forgetting that content in adult life, which is removed from educational institutions (Shamos 1995). Thus, within the environment of interaction where scientific knowledge is created and utilised, it is possible to see a relatively strong tendency to strengthen precautionary attitudes towards science and technology; at the same time in this environment it is observed that there is a higher level of understanding of scientific content. Although the data are not enough to carry out a more consistent test on these affirmations, we think it leaves the door open for future explorations with significant empirical, theoretical and political consequences.

Conclusions

In this study we have explored some indicators of the valuation of science and technology by the public. This public consists of inhabitants of a modern city that is located in a periphery country, both as regards international politics and economy, and the production of science and technology. We have seen that the predominant perception confirms the advantages of scientific knowledge, evaluating it in terms of utility and grounds of modern culture, although it points out, at the same time, its limits and negative effects, considering science a strange force, beneficial but incomprehensible and turbulent for the world. In this sense, we have observed that the data reinforce the idea of trust in science as an expert system characteristic of modernity, but they also reinforce the uncertainty generated by controversies in science and in the application of technology. This enables us to classify the surveyed population in terms of the concept of risk society, which is a characteristic feature of reflexive modernity. On the other hand we have pointed out the lack of correlation among the valuation indicators, which seems to reflect an ambivalent culture towards science and technology. Although we can only account for such ambivalence as a mere disparity of judgement between positive and negative values towards science and technology, we have tried to formulate some hypotheses about its origin. The data available do not enable us to further explore these hypotheses; nevertheless, they may be used as guidelines for future research. The ambivalence can be seen in the four types

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

161

of orientations towards science and technology which has been provided to us by factor analysis. According to this, we have described two positive and two negative orientations. The first ones are differentiated due to the higher value of utility allocated to science or to a more unconditional and nave adherence to its good qualities. The negative ones comprise a critical vision of science and technology that is based on the lack of sciences commitment to society, and another vision based on the traditional perspective and that which rejects science as a disturbing factor of traditional life. These orientations coexist within the agents subjective space, giving shape to its responses, without resulting in social groups or parties among the public. Last, we questioned the positive relation between education and the valuation of science and technology. We observed that in the case of many indicators, a higher level of education or knowledge does not imply a more positive valuation of science, but that it is in fact the other way round in the case of some indicators. We also did some empirical tests, which, though weak, indicated that the valuations of science tend to be more critical in contexts where the interaction in terms of knowledge is high (universities). We suggest, then, that this should open a research line with relevant and countless theoretical and political consequences.

NOTES

1. The survey was carried out in 2002 and covered a random sample of 300 cases. A description of the study and its main comparative results with other cities of IberoAmerican countries can be found in Albornoz et al. (2003). 2. Before being applied, the questionnaire was subject to revision by a discussion group of eleven people who analysed the meaning allocated to each prompt. There was an immediate agreement about this question in particular. 3. In spite of this, some authors have indicated Becks exaggeration in considering this perception of the public particularly important in the relation between society and scientific knowledge. See Yearley (2000). 4. Ambivalence is only given an operational meaning due to the lack of association between indicators of positive and negative valuation towards science and technology. 5. We do not include methodological errors as hypotheses in the design of indicators. The fact that the ambiguity of responses has been made evident in other empirical studies allows us to avoid the methodological hypothesis (see, for example, Eurobarmetro 55.2 2001). 6. Apart from the sixteen used in the previous section, two indicators were added: the one we already used to differentiate the two basic orientations of trust and precaution, and another presented in the following affirmation: Scientific knowledge improves peoples ability to decide important things in life.

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

162

Leonardo Silvio Vaccarezza

7. The same analysis cannot be carried out at the other educational levels. In the case of those who have a complete level, attendance of educational institutions is almost nonexistent. At other incomplete levels the number of cases (either among those who do attend or among those that do not currently do so) is very low.

REFERENCES

Albornoz, Mario, Leonardo Vaccarezza, Carmelo Polino and Mara Eugenia Fazio (2003), Resultados de la Encuesta de Percepcin Pblica de la Ciencia Realizada en Argentina, Brasil, Espaa y Uruguay. Buenos Aires: RICYT/CYTEDOEI. http://www. centroredes.org.ar/documentos/files/Doc.Nro9.pdf. Beck, Ulrich (1992), Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Publications. (1999), World Risk Society. London: Polity Press-Blackwell. Bensaude-Vincent, Bernadette (2001), A Genealogy of the Incresing Gap between Science and the Public, Public Understanding of Science, 10(1), pp. 99113. Collins, H.M. and R. Evans (2002). The Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience, Social Studies of Science, 32(2), pp. 23596. Dagnino, Renato and Hernn Thomas (1999), La Poltica Cientfica y Tecnolgica en Amrica Latina: Nuevos Escenarios y el Papel de la Comunidad de Investigacin, Revista REDES, 6(13), pp. 4974. Davison, Aidan, Ian Barns and Renato Schibeci (1997), Problematic Publics: A Critical Review of Surveys of Public Attitudes to Biotechnology, Science, Technology and Human Value, 22(3), pp. 31748. Eurobarmetro 55.2 (2001), Europeans, Science and Technology. Brussels: EORG. Fourez, Grard (1997), Scientific and Technological Literacy as a Social Practice, Social Studies of Science, 27(6), pp. 90336. Giddens, Antony (1990), The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. Irwing, Alan (2001), Constructing the Scientific Citizen: Science and Democracy in Biosciences, Public Understanding of Science, 10(1), pp. 118. Lee, Stuart and Wolf-Michael Roth (2003), Science and the Good Citizen: Communitybased Scientific Literacy, Science, Technology and Human Value, 28(3), pp. 40324. Lujn, Jos L. and Oliver Todt (2000), Perceptions, Attitudes and Ethical Valuations: The Ambivalence of the Public Image of Biotechnology in Spain, Public Understanding of Science, 9(4), pp. 38392. Michael, Mike (2002), Comprehension, Apprehension, Prehension: Heterogeneity and the Public Understanding of Science, Science, Technology and Human Values, 27(3), pp. 35778. Miller, J.D., R. Pardo and F. Niwa (1998), Percepciones del Pblico Ante la Ciencia y la Tecnologa: Estudio Comparativo de la Unin Europea, Estados Unidos, Japn y Canad, Bilbao: Fundacin Banco Bilbao Vizcaya. Moscovici, Serge and Ivana Morkov (1998), Presenting Social Representation: A Conversation, Culture & Psychology, 4(3) pp. 371410. Shamos, Morris H. (1995), The Myth of Scientific Literacy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF S&T IN A PERIPHERY SOCIETY

163

Wynne, Brian (1995), Public Understanding of Science, in Sheila Jasanoff et al., eds, Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. London: Sage Publications, pp. 36188. Yearley, Steven (2000), Making Systematic Sense of Public Discontents with Expert Knowledge: Two Analytical Approaches and a Case Study, Public Understanding of Science, 9(2), pp. 10522. Ziman, John (2000), Real Science: What it is, and what it means. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2003), Ciencia y Sociedad Civil, Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnologa y Sociedad, 1(1), pp. 17788.

Downloaded from sts.sagepub.com at Tubitak Ulakbim on October 7, 2011

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Quantitative Measurement, Reliablity, ValidityДокумент36 страницQuantitative Measurement, Reliablity, ValidityDiana Rizky YulizaОценок пока нет

- The Economics of Technical DevelopmentДокумент5 страницThe Economics of Technical DevelopmentCan BayraktarОценок пока нет

- The Hacker EthicДокумент257 страницThe Hacker EthicCan Bayraktar100% (1)

- HOBSBAWM Eric J Age of ExtremeДокумент336 страницHOBSBAWM Eric J Age of ExtremeMaxОценок пока нет

- On The Genealogy of Information - CapurroДокумент8 страницOn The Genealogy of Information - CapurroCan BayraktarОценок пока нет

- The Concept of Information - CapurroДокумент28 страницThe Concept of Information - CapurroCan BayraktarОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan in Physical EducationДокумент4 страницыLesson Plan in Physical EducationGemmalyn DeVilla De CastroОценок пока нет

- A Deep Learning Architecture For Semantic Address MatchingДокумент19 страницA Deep Learning Architecture For Semantic Address MatchingJuan Ignacio Pedro SolisОценок пока нет

- Theatre For Social Change Lesson Plan OneДокумент2 страницыTheatre For Social Change Lesson Plan OneSamuel James KingsburyОценок пока нет

- Scope and Limitation of The Study in Social Research: Research. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press. Pp. 105-114Документ11 страницScope and Limitation of The Study in Social Research: Research. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press. Pp. 105-114Cristine LaranjaОценок пока нет

- Stylistics Paper UpdatedДокумент5 страницStylistics Paper UpdatedHot Bollywood HubОценок пока нет

- Learning Log Week 1-2Документ2 страницыLearning Log Week 1-2KingJayson Pacman06Оценок пока нет

- Brief History of PsychologyДокумент3 страницыBrief History of PsychologyMaria TariqОценок пока нет

- Training and DevelopmentДокумент15 страницTraining and Developmentmarylynatimango135100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayДокумент4 страницыDaily Lesson Log: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayMark A. SolivaОценок пока нет

- Coaching ToolkitДокумент7 страницCoaching ToolkitTrebor ZurcОценок пока нет

- FS 1 Episode 7Документ4 страницыFS 1 Episode 7Mike OptimalesОценок пока нет

- Semantics exam questions and answersДокумент4 страницыSemantics exam questions and answersThiên Huy100% (1)

- G11 - Q3 - LAS - Week5 - Reading and WritingДокумент8 страницG11 - Q3 - LAS - Week5 - Reading and WritingRubenОценок пока нет

- GTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationДокумент2 страницыGTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationDanny SolvanОценок пока нет

- PRE - Lecture 2 - How To Write A Research PaperДокумент7 страницPRE - Lecture 2 - How To Write A Research PaperPaupauОценок пока нет

- Monitoring Form: Grade 12 Career Guidance ModuleДокумент2 страницыMonitoring Form: Grade 12 Career Guidance ModuleJC Rick Gel CaguisaОценок пока нет

- Edtpa Lesson 3Документ4 страницыEdtpa Lesson 3api-511022719Оценок пока нет

- Personal Development Module 4 Q1Документ17 страницPersonal Development Module 4 Q1Jay IsorenaОценок пока нет

- Derivatives of Complex Functions: Bernd SCHR OderДокумент106 страницDerivatives of Complex Functions: Bernd SCHR OderMuhammad Rehan QureshiОценок пока нет

- Giver Edguide v4bДокумент28 страницGiver Edguide v4bapi-337023605Оценок пока нет

- Design Thinking RahulДокумент2 страницыDesign Thinking RahulRahul Kumar NathОценок пока нет

- FOCUS-4 kl-12 FIRST PERIOD 2018.2019Документ5 страницFOCUS-4 kl-12 FIRST PERIOD 2018.2019ІванОценок пока нет

- Sample Quali ASMR - ManuscriptДокумент26 страницSample Quali ASMR - ManuscriptKirzten Avril R. AlvarezОценок пока нет

- Concept Map Rubric Scoring GuideДокумент1 страницаConcept Map Rubric Scoring GuideAJA TVОценок пока нет

- The Case of Big Sarge: Overcoming Depression and Low Self-WorthДокумент18 страницThe Case of Big Sarge: Overcoming Depression and Low Self-WorthDennis HigginsОценок пока нет

- OCC324 Reading ListДокумент4 страницыOCC324 Reading ListMUNIRA ALTHUKAIRОценок пока нет

- Donahue - PlaxtonMoore - Student Companion To CEL-IntroДокумент8 страницDonahue - PlaxtonMoore - Student Companion To CEL-Introkarma colaОценок пока нет

- Mathematics-guide-for-use-from-September-2020 January-2021Документ63 страницыMathematics-guide-for-use-from-September-2020 January-2021krisnaОценок пока нет

- Strategy For Teaching MathematicsДокумент202 страницыStrategy For Teaching MathematicsRishie Kumar Loganathan100% (4)