Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Spivak Cornell Et Al - Nussbaum and Her Critics

Загружено:

jamesbliss0Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Spivak Cornell Et Al - Nussbaum and Her Critics

Загружено:

jamesbliss0Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

The New Republic APRIL 19, 1999 Martha C. Nussbaum and Her Critics: An Exchange SECTION: Pg.

46 LENGTH: 2847 words To the editors: In a recent issue ("The Professor of Parody," February 22), as an example of gullibility in the face of obscure prose, Martha C. Nussbaum trots out a secondhand quotation where I reputedly opine that Judith Butler is "probably one of the ten smartest people on the planet." Had Nussbaum verified the quotation instead of citing a citation, she would have found a literary theory website introducing "The Grand PoohBahs: Often Named Jacques, but also Helene, Luce, Michel, and occasionally Fred" (which also features Michel Foucault's head pasted atop a Pez dispenser). The original quote: "Judith Butler's ideas are sophisticated enough that people usually simplify them in cartoonish ways. Engaging her in a profound way necessitates an understanding of an intimidating list of difficult thinkers... . Probably one of the ten smartest people on the planet, and damn her--he said admiringly--she's only 34." It's called irony. Discerning readers are welcome to join me. Without doubt, theory-minded academics often dismiss objections with unwarranted impatience. But when selfappointed defenders of clarity are unwilling to do the basic research we would require of any first-year composition student, perhaps that impatience is warranted. For the original, campy discussion of Butler (and now, Nussbaum) visit: www.sou. edu/English/IDTC/Swirl/ swirl.htm.

Warren Hedges Assistant Professor of English Southern Oregon University Ashland, Oregon To the editors: In her recent review of Judith Butler's work, Martha C. Nussbaum complains that feminists like Butler "find comfort in the idea that the subversive use of words is still available to feminist intellectuals." Her own essay is a better example of this confidence than anything written by Judith Butler. Nussbaum believes that socialconstruction theories are the same as the analysis of gender as performative. And she will not allow Butler the freedom of expanding the Austinian performative into a more than verbal category. Since she so berates Butler for being impractical, she should have reckoned that social construction of gender theories being around since Plato is not quite the same thing as an intellectual pointing out that we all make gender come into being by doing it. Butler's performative theory is not the same as Austin's and not the same as social construction theories. She is addressing conventions in use, social contract-effects, collective

"institutions" of elusive materiality, the ground of the political. No legal or political reform stands a chance of survival without tangling with conventions. As an Indian feminist theorist and activist resident in the United States and honored by the friendship of such subcontinental feminist activists as Flavia Agnes, Farida Akhter, Mahasweta Devi, Madhu Kishwar, Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, Romila Thapar, Susie Tharu, and many others, I refuse the implicit matronizing reference to "rape law in India today, which has most of the flaws that the first generation of American feminists targeted" with which Nussbaum opens her subplot of Indian feminists as an example of what Butler is not. (How are we to treat Anupama Rao's serious consideration of Butler in "Understanding Sirsgaon: Notes Toward Conceptualising the Role of Law, Caste and Gender in a Case of 'Atrocity,'" for example? Instances of the use of Butler by Indian feminist theorists can be multiplied.) This flag-waving championship of needy women leads Nussbaum finally to assert that "women who are hungry, illiterate, disenfranchised, beaten, raped ... prefer food, schools, votes, and the integrity of their bodies." Sounds good, from a powerful tenured academic in a liberal university. But how does she know? This may be her idea of what they should want. In that conviction she may want to train them to want this. That is called a "civilizing mission. " But if she ever engages in unmediated grassroots activism in the global South, rather than championing activist theorists, she will find that the gender practice of the rural poor is quite often in the performative mode, carving out power within a more general scene of pleasure in subjection. If she wants to deny this generality of gender culture and make the women over in her own image, she will have to enter their protocol, and learn much greater patience and understanding than is shown by this vicious review. "Butler's hip quietism ... collaborates with evil," Nussbaum concludes. Any involvement with counterglobalization would show how her unexamined, and equally hip, U.S. benevolence toward "other women" collaborates with exploitation. The solution, if there is any, is not to engage in abusive reviews in the pages of national journals. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities Columbia University New York, New York To the editors: We were disturbed by Martha C. Nussbaum's attack on Judith Butler in the February 22 issue of The New Republic. One element we found particularly objectionable was Nussbaum's repeated attempts to dismiss Butler as a philosopher. At one point Nussbaum claims that Butler is seen as a major thinker "more by people in literature than by philosophers." She asks whether Butler's manner of writing "belongs to the philosophical tradition at all." As one who has contributed much to bringing literature and philosophy closer together, Nussbaum's questioning of Butler's attempts are disingenuous. Furthermore, Nussbaum's move is reminiscent of those who have tried to keep feminist concerns out of philosophy on grounds " that this is just not philosophy." While Nussbaum raises some worthwhile questions, the element of vituperativeness in the essay is disturbing. Butler's contributions are not only described as "unconscionably bad" but the quietism Nussbaum claims to follow from them is said "to collaborate with evil." This rhetoric of overkill stands in striking contrast to the

unquestioning adulation Nussbaum gives to Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin. Given the authoritarian strains in the politics of MacKinnon and Dworkin, Butler's strong antiauthoritarianism is a useful antidote. Seyla Benhabib Professor of Government Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts Nancy Fraser Professor of Political Science and Philosophy The New School for Social Research New York, New York Linda Nicholson The State University of New York, Albany Albany, New York To the editors: Martha C. Nussbaum's review of Judith Butler takes as its premise the belief that the test of a theory's goodness is its positive political outcome. Yet we are offered no empirical evidence for this claim. Instead, we are presented with a manichean scheme which defines "good" theory as that which " is closely tethered to practical commitments," to "real" issues, to "the real situation of real women," to "real politics" and "real justice." It is irrelevant to Nussbaum's polemic that Judith Butler is on record in word and deed as a politically concerned person with "practical commitments" to "real politics," and that her writings have influenced what even Nussbaum would take to be "good" politics among Queer activists, feminist psychoanalysts, and lawyers working on women's rights. According to the logic of the argument, since Butler does not share Nussbaum's "normative theory of social justice and human dignity," Butler can only "collaborate with evil." In the guise of a serious book review, Nussbaum has constructed a self-serving morality tale in which she (along with Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin) represents historically authentic and politically efficacious feminism, while Judith Butler (and the young, Francophile, sado-masochist minions who are said to follow her) indulge in "amoral anarchist politics" or "hip quietism" and so betray feminist goals. Nussbaum conveniently omits all discussion of instances of "real" politics in her article, perhaps because the evidence is so damning to her argument. To deduce politics from theory, as Nussbaum does, is to misunderstand the operations of both. The job of theory is to open new avenues of understanding, to trouble conventional wisdom with difficult questions. The job of politics (in democratic societies, at least) is to secure some end in a contested, conflictual field. Politics and theory may inform one another at certain moments with successful or

unsuccessful results--the outcomes are not predictable. Historically, though, one thing is sure: when the gap between theory and politics is closed in the name of virtue, when Robespierre or the Ayatollahs or Ken Starr seek to impose their vision of the "good" on the rest of society, reigns of terror follow and democratic politics are undermined. These are situations in which, to reverse Martha Nussbaum's reasoning, too much "good" ends up as "evil," and feminism, along with all other emancipatory movements, loses its public voice. Sadly, Nussbaum's good versus evil scheme substitutes moralist fundamentalism for genuine philosophical and political debate among feminists- -and there is much to be debated these days: Are all "women" the same? Who can speak for the needs and interests of "women"? How can political action address deeply rooted conventions about gender? Judith Butler has engaged these questions with great honesty and skill. Those of us looking for ways of reflecting on the situation of feminism today understandably prefer the provocative, open theories of Judith Butler to the closed moralizing of Martha Nussbaum. Joan W. Scott Professor of Social Science Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, New Jersey To the editors: Are feminist theorists now divisible into two distinct groups, the activists and the "hip defeatists"? While Martha C. Nussbaum raises some serious issues about the relation between feminist theory and the day-to-day struggles of women around the world to achieve recognition of their dignity, her dichotomy between those feminists who are "materialists" and those of a " new symbolic type" who "believe that the way to do feminist politics is to use words in a subversive way, in academic publications of lofty obscurity and disdainful abstraction" is not only simplistic but obscures the crucial focus of second-wave feminism on the role of representations in shaping our reality. We don't think that any feminist, Judith Butler included, believes that feminist political goals can be achieved in the ways attributed by Nussbaum to this "new symbolic type." But feminists of all stripes-- as well as many other groups in the second half of this century--have long seen that questions of how we represent ourselves and are represented by others are central to the quest for justice. In her article, Nussbaum contrasts Catharine MacKinnon as the exemplar "good" activist feminist to Judith Butler, her epitome of the "bad" languageoriented feminist. Yet for both MacKinnon and Butler, feminist work is grounded in an insistence upon the material force of representations, linguistic as well as visual. Catharine MacKinnon and other antiporn feminists have taught us that pornographic images and words brutalize us as women and that resisting repression means finding ways out of these representations. Judith Butler's work, including her rightfully famous insight into the performative aspect of identity, likewise focuses on the ways in which representations have constitutive force, the way in which who we are is deeply connected with how we are represented. But whereas MacKinnon's focus on the materiality of representation has turned toward legal reform, including the creation of an innovative civil rights ordinance written with Andrea Dworkin, Butler has argued that the struggle over representations should be fought out in politics. This is a real difference between them and needs to be addressed. Feminist theorists, including one of the authors, have sought for years now to address this question of the parameters of legal reform and the possibilities of change through politics. Part of this involves a problem that has historically plagued analytic jurisprudence: How do we reconcile freedom and equality in a concept of right?

Given the stakes and seriousness of the work of these two theorists as well as the complexity that their work-and that of many, many others--seeks to address, Nussbaum's facile division of theorists into two camps is not only inaccurate, it is less than productive. Reading her essay, actually not much more than an ad feminam attack on Butler, one is indeed reminded--if ironically, if paradoxically--of David Hume, whom Nussbaum accurately characterizes as "a fine ... a gracious spirit: how kindly he respects the reader's intelligence, even at the cost of exposing his own uncertainty." Would that Martha Nussbaum had honored Hume's philosophical spirit in her own review of Judith Butler's work. Drucilla Cornell Professor of Law, Political Science, and Women's Studies Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey Sara Murphy Lecturer Gallatin School, New York University New York, New York Martha C. Nussbaum replies: Hedges's letter shows that I quoted him correctly. The larger context of his remark suggests that it may be hyperbolic; there is no sign that it is ironic. Perhaps Hedges confuses these two concepts. Spivak is wrong to say that I equate social-construction theories with the thesis that gender is performative. I said that the latter, though built on the former, was Butler's one interesting new contribution. Butler can of course expand on Austin as she likes, but my claim was that Austin's views, which in any case she misrepresents, do not help her much with the project that she is pursuing. I admire Spivak's work with tribal women: indeed I was thinking of it when I wrote that feminists in India, whatever their intellectual orientation, remain close to practical problems. But she should inquire about what I do before she makes assumptions. I have spent a lot of time during the past few years with activists and women's development projects in India. I have visited projects of many different types in different regions. I have never yet met a poor woman who told me she took pleasure in subjection, though there may be some who do. I have met countless women who struggle for access to credit, education, employment opportunities, political representation, and shelter from domestic violence. My claims about rape law in India are correct: a victim's sexual history, for example, is still relevant evidence. I believe that there is nothing " matronizing" about making American readers aware of the fine work being done in this area by activists such as Indira Jaising, for whose advice and illumination I am grateful. In my forthcoming book, Women and Human Development, my claims about women in India are amply documented, as was not possible in a brief review.

Benhabib, Fraser, and Nicholson say that my claim that Butler is more sophist than philosopher is "disingenuous" because I have written that philosophy can derive insight from literature. This odd non sequitur might be valid if one supplied the tacit premise that sophistry is literature, or that Butler is a figure comparable to Proust and Henry James. But I see no reason to accept either of those assumptions. What I called "unconscionably bad" was not Butler's work in general, but her use of First Amendment legal materials in Excitable Speech. In that context, the phrase is appropriate. Finally, anyone who reads what I have written about MacKinnon and Dworkin will know that my attitude to them is not one of "unquestioning adulation," but rather of deeply respectful criticism. Scott misses an important distinction. I was talking not about practical activities pursued by theorists, but about theorizing in a way that gives direction to practical political efforts. Butler may well have admirable practical commitments, but this does not change the fact that what she writes as a theorist offers no helpful direction for practice. I discussed many examples of theorizing that does provide such a direction, including writings about the reform of rape law, sexual harassment law, and the concept of sex equality more generally. Nor do I see how the scare-names of the Ayatollah and Robespierre undermine the value of the work of feminists who have helped make progress in legal reform. Cornell and Murphy write an interesting letter that goes to the substance of what I actually argued. They are correct in noting that MacKinnon's thought has a significant symbolic dimension. The differences between MacKinnon and Foucault deserve a subtle investigation. I hope they will write such a study. Far from dividing thinkers into two camps, I made it clear that I respect some work in the Foucauldian-Symbolic tradition, including the work of Foucault himself. Butler doesn't seem to me a thinker of the same caliber.

Вам также может понравиться

- ASHENDEN (Ed.) Foucault Contra Habermas PDFДокумент229 страницASHENDEN (Ed.) Foucault Contra Habermas PDFLucasTrindade880% (1)

- Rethinking Power Mark HaugaardДокумент30 страницRethinking Power Mark HaugaardhareramaaОценок пока нет

- Caudill, Lacan, Science, and LawДокумент24 страницыCaudill, Lacan, Science, and LawAndrew ThorntonОценок пока нет

- Nationalist Projects and Gender Relations: Nira Yuval-Davis University of Greenwich, LondonДокумент28 страницNationalist Projects and Gender Relations: Nira Yuval-Davis University of Greenwich, LondonatelocinaОценок пока нет

- Benhabib - Moving Beyond False Binarisms On Samuel Moyn's The Last Utopia (2013)Документ14 страницBenhabib - Moving Beyond False Binarisms On Samuel Moyn's The Last Utopia (2013)Anita Hassan Ali SilveiraОценок пока нет

- Contra Voegelin: Getting Islam Straight - Charles E. ButterworthДокумент20 страницContra Voegelin: Getting Islam Straight - Charles E. ButterworthSamir Al-Hamed100% (1)

- Politics, Shamelessness and the Rise of an Exclusionary DemosДокумент16 страницPolitics, Shamelessness and the Rise of an Exclusionary DemosBenjamin ArditiОценок пока нет

- Machiavelli's Concept of VirtùДокумент31 страницаMachiavelli's Concept of VirtùalejandraОценок пока нет

- How Many Grains Make A Heap (Rorty)Документ10 страницHow Many Grains Make A Heap (Rorty)dhstyjntОценок пока нет

- Eden Review of Berkowitz and LampertДокумент2 страницыEden Review of Berkowitz and Lampertsyminkov8016Оценок пока нет

- Marx and Darwin: A Reconsideration Author(s) : Terence Ball Reviewed Work(s) : Source: Political Theory, Vol. 7, No. 4 (Nov., 1979), Pp. 469-483 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 22/04/2012 07:24Документ16 страницMarx and Darwin: A Reconsideration Author(s) : Terence Ball Reviewed Work(s) : Source: Political Theory, Vol. 7, No. 4 (Nov., 1979), Pp. 469-483 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 22/04/2012 07:24AnthriqueОценок пока нет

- Windelband, History of Philosophy, Vol. 1Документ398 страницWindelband, History of Philosophy, Vol. 1maivin2Оценок пока нет

- The Conditioning of The UnconditionedДокумент14 страницThe Conditioning of The UnconditionedanimalismsОценок пока нет

- Kulick Masochist AnthropologyДокумент20 страницKulick Masochist AnthropologyTemirbek BolotОценок пока нет

- Derrida, Declarations of IndependenceДокумент5 страницDerrida, Declarations of IndependencereditisОценок пока нет

- Marx's Engagement with Darwin's Evolutionary TheoryДокумент10 страницMarx's Engagement with Darwin's Evolutionary TheoryAli AziziОценок пока нет

- Fredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016Документ19 страницFredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016madspeterОценок пока нет

- Journal of Political Philosophy Volume 13 Issue 1 2005 (Doi 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2005.00211.x) Jürgen Habermas - Equal Treatment of Cultures and The Limits of Postmodern Liberalism PDFДокумент29 страницJournal of Political Philosophy Volume 13 Issue 1 2005 (Doi 10.1111/j.1467-9760.2005.00211.x) Jürgen Habermas - Equal Treatment of Cultures and The Limits of Postmodern Liberalism PDFLuna Aps MartinsОценок пока нет

- Althusser The Detour of Theory PDFДокумент112 страницAlthusser The Detour of Theory PDFCathy GoОценок пока нет

- Women's Lives - Feminist Knowledge - Feminist Standpoint As Ideology Critique - Hennessy, RosemaryДокумент22 страницыWomen's Lives - Feminist Knowledge - Feminist Standpoint As Ideology Critique - Hennessy, RosemaryElena Bolio LópezОценок пока нет

- Marx and Darwin: How their ideas shaped modern thoughtДокумент23 страницыMarx and Darwin: How their ideas shaped modern thoughtdgar78Оценок пока нет

- Performativity and Pedagogy: The Making of Educational SubjectsДокумент8 страницPerformativity and Pedagogy: The Making of Educational SubjectsPsicología Educativa LUZ-COLОценок пока нет

- David Strauss: The Confessor and WriterДокумент3 страницыDavid Strauss: The Confessor and Writerevan karpОценок пока нет

- Michael Huemer - The Problem of Authority PDFДокумент8 страницMichael Huemer - The Problem of Authority PDFJres CfmОценок пока нет

- The Age of Capital: 1848-1875 - Eric HobsbawmДокумент4 страницыThe Age of Capital: 1848-1875 - Eric HobsbawmcyloboruОценок пока нет

- Strathausen - Myth or KnowledgeДокумент23 страницыStrathausen - Myth or KnowledgeNicolás AldunateОценок пока нет

- Lefort - Politics and Human RightsДокумент24 страницыLefort - Politics and Human RightssunyoungparkОценок пока нет

- The Mismeasure of Man Gould PDFДокумент3 страницыThe Mismeasure of Man Gould PDFMarcus0% (1)

- LEVINE 1981 Sociological InquiryДокумент21 страницаLEVINE 1981 Sociological Inquirytarou6340Оценок пока нет

- Carl Schmitt, Political Romanticism, Translated by Guy Oakes, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 168 PPДокумент4 страницыCarl Schmitt, Political Romanticism, Translated by Guy Oakes, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 168 PPAlejandro FielbaumОценок пока нет

- Race in Anthropology 2011 - MacEachern PDFДокумент24 страницыRace in Anthropology 2011 - MacEachern PDFScott MacEachernОценок пока нет

- The Necessity of Freedom (A Critique of Michel Foucault) Suther JensenДокумент34 страницыThe Necessity of Freedom (A Critique of Michel Foucault) Suther JensenΓιώργος ΕγελίδηςОценок пока нет

- Conant (1998) Wittgenstein On Meaning and UseДокумент29 страницConant (1998) Wittgenstein On Meaning and UseMariane Farias100% (1)

- Bloch, Ernst "Karl Marx Death and The Apocalypse"Документ28 страницBloch, Ernst "Karl Marx Death and The Apocalypse"mkhouseОценок пока нет

- PATTON, Paul - Foucault's Subject of Power - Political Theory NewsletterДокумент13 страницPATTON, Paul - Foucault's Subject of Power - Political Theory NewsletterAlekseiОценок пока нет

- The Authenticity of The Thing-In-Itself: Kant, Brentano, and HeideggerДокумент12 страницThe Authenticity of The Thing-In-Itself: Kant, Brentano, and HeideggerFranklin Tyler FehrmanОценок пока нет

- Nature History and Aristotles Best Polis Josiah OberДокумент20 страницNature History and Aristotles Best Polis Josiah OberanОценок пока нет

- Review of Essays on Individualism and Two Other WorksДокумент4 страницыReview of Essays on Individualism and Two Other Worksbolontiku9Оценок пока нет

- Carens Aliens and Citizens The Case For Open BordersДокумент24 страницыCarens Aliens and Citizens The Case For Open BordersSwastee RanjanОценок пока нет

- (SUNY Series in Social and Political Thought) Günther, Klaus - The Sense of Appropriateness - Application Discourses in Morality and Law (1993, State University of New York Press)Документ387 страниц(SUNY Series in Social and Political Thought) Günther, Klaus - The Sense of Appropriateness - Application Discourses in Morality and Law (1993, State University of New York Press)Agustín De LucaОценок пока нет

- Fact and Fiction in The History of Scientific Discovery PDFДокумент2 страницыFact and Fiction in The History of Scientific Discovery PDFPerlaОценок пока нет

- WRIGHT, Coling. Post-Truth, Postmodernism and Alternative Facts.Документ15 страницWRIGHT, Coling. Post-Truth, Postmodernism and Alternative Facts.Hully GuedesОценок пока нет

- Why Nozick Is Not So Easy To RefuteДокумент3 страницыWhy Nozick Is Not So Easy To Refutealienboy97Оценок пока нет

- Abu-Lughod, Writing Against CultureДокумент14 страницAbu-Lughod, Writing Against CultureCarlos Eduardo Olaya Diaz100% (1)

- A Reply To Can Marxism Make Sense of CrimeДокумент7 страницA Reply To Can Marxism Make Sense of CrimeYakir SagalОценок пока нет

- Critical Crimin OlogiesДокумент28 страницCritical Crimin OlogiespurushotamОценок пока нет

- Indigenous Experience Today SymposiumДокумент17 страницIndigenous Experience Today SymposiumJoeОценок пока нет

- Line Schjolden Suing For Justice (Tesis)Документ301 страницаLine Schjolden Suing For Justice (Tesis)Anonymous W1vBbIE4uyОценок пока нет

- Michael Ruse CVДокумент23 страницыMichael Ruse CVMichael AndritsopoulosОценок пока нет

- Bourdieu Scholastic Point of ViewДокумент13 страницBourdieu Scholastic Point of ViewFranck LОценок пока нет

- Barbara Johnson's PublicationsДокумент3 страницыBarbara Johnson's PublicationsR BОценок пока нет

- John Keane Civil Society and The StateДокумент63 страницыJohn Keane Civil Society and The StateLee ThachОценок пока нет

- SchelskyДокумент11 страницSchelskyJhan Carlo VeneroОценок пока нет

- Simon Schwartzman A Space For Science PDFДокумент154 страницыSimon Schwartzman A Space For Science PDFLucasTramontanoОценок пока нет

- Jon ELSTER (1992) - Local Justice. How Institutions Allocate Scarce Goods and Necessary BurdensДокумент291 страницаJon ELSTER (1992) - Local Justice. How Institutions Allocate Scarce Goods and Necessary BurdensJorgeОценок пока нет

- The Revolutionary Tradition and Its Lost TreasureДокумент3 страницыThe Revolutionary Tradition and Its Lost TreasureEnsari EroğluОценок пока нет

- Interview of Bernard Manin and Nadia UrbinatiДокумент18 страницInterview of Bernard Manin and Nadia UrbinatiElgin BaylorОценок пока нет

- On the Political Stupidity of JewsДокумент4 страницыOn the Political Stupidity of Jewsplouise37Оценок пока нет

- 21313213Документ37 страниц21313213Shaahin AzmounОценок пока нет

- LAPD Racial Profiling Report - ACLUДокумент59 страницLAPD Racial Profiling Report - ACLUBento SpinozaОценок пока нет

- Jared Sexton, Life With No HoopДокумент13 страницJared Sexton, Life With No Hoopjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Adorno ND EndnotesДокумент12 страницAdorno ND Endnotesjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Bliss - Hope Against HopeДокумент17 страницBliss - Hope Against Hopejamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Beverly Smith, 'Diane'Документ6 страницBeverly Smith, 'Diane'jamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Southern Exposure - Southern Black Utterances TodayДокумент64 страницыSouthern Exposure - Southern Black Utterances Todayjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Hortense Spillers, "Brother Isom"Документ14 страницHortense Spillers, "Brother Isom"jamesbliss0100% (1)

- Kipnis AdulteryДокумент40 страницKipnis Adulteryjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Bambara - What It Is I Think Im Doing AnyhowДокумент11 страницBambara - What It Is I Think Im Doing Anyhowjamesbliss0100% (9)

- Bambara - The ApprenticeДокумент12 страницBambara - The Apprenticejamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Fred Moten - Blackness and NothingnessДокумент44 страницыFred Moten - Blackness and Nothingnessdocbrown85100% (6)

- Spillers - Whatcha Gonna DoДокумент12 страницSpillers - Whatcha Gonna Dojamesbliss0100% (4)

- Frieda Ekotto - Against Representation: Countless Hours For A ProfessorДокумент5 страницFrieda Ekotto - Against Representation: Countless Hours For A Professorjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Antz Fanons Rebel Intellectual in Search of A Black CyborgДокумент14 страницAntz Fanons Rebel Intellectual in Search of A Black Cyborgjamesbliss0100% (1)

- Martinot / Sexton: The Avant Garde of White SupremacyДокумент15 страницMartinot / Sexton: The Avant Garde of White Supremacyjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Hartman Wilderson - Position of The UnthoughtДокумент20 страницHartman Wilderson - Position of The Unthoughtjamesbliss0100% (3)

- Martinot / Sexton: The Avant Garde of White SupremacyДокумент15 страницMartinot / Sexton: The Avant Garde of White Supremacyjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Sexton - The Obscurity of Black SufferingДокумент9 страницSexton - The Obscurity of Black Sufferingjamesbliss0100% (4)

- Mitchell Staeheli - Permitting ProtestДокумент18 страницMitchell Staeheli - Permitting Protestjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- JohnsonKimberley - Political HairДокумент24 страницыJohnsonKimberley - Political Hairjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Snead - Racist Traces in Postmodernist Theory and LiteratureДокумент11 страницSnead - Racist Traces in Postmodernist Theory and Literaturejamesbliss0100% (1)

- Woods - Fact of Anti BlacknessДокумент11 страницWoods - Fact of Anti Blacknessjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Wilderson - The Vengeance of Vertigo - Aphasia and Abjection in The Political Trials of Black InsurgentsДокумент41 страницаWilderson - The Vengeance of Vertigo - Aphasia and Abjection in The Political Trials of Black InsurgentsK-Sue ParkОценок пока нет

- Satcher-Troutman-Etal - What If We Were EqualДокумент7 страницSatcher-Troutman-Etal - What If We Were Equaljamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Weizman ThanatotacticsДокумент14 страницWeizman Thanatotacticsjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- From Slavery To Mass IncarcerationДокумент20 страницFrom Slavery To Mass Incarcerationco9117100% (2)

- Sexton - People of Color SocTxtДокумент26 страницSexton - People of Color SocTxtjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Sexton RacialprofilingДокумент12 страницSexton Racialprofilingjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Ahmed - Embodying Diversity Problems and Paradoxes For Black FeministsДокумент13 страницAhmed - Embodying Diversity Problems and Paradoxes For Black Feministsjamesbliss0Оценок пока нет

- Conversation With Kathy AckerДокумент11 страницConversation With Kathy AckerImpossible MikeОценок пока нет

- Andrea DWORKIN Right Wing Women The Politics of Domesticated Females 19831Документ249 страницAndrea DWORKIN Right Wing Women The Politics of Domesticated Females 19831sdflbc100% (4)

- Andrea Dworkin OmnibusДокумент232 страницыAndrea Dworkin OmnibusΣπύρος Μαρκέτος100% (3)

- Feminist QuotesДокумент6 страницFeminist QuotesQuotesОценок пока нет

- Not A Moral Issue MACKINNON PDFДокумент25 страницNot A Moral Issue MACKINNON PDFFeminismo InvestigacionОценок пока нет

- Andrea Dworkin A Detrement To The Feminist MovementДокумент3 страницыAndrea Dworkin A Detrement To The Feminist Movementkaushik_1991Оценок пока нет

- Nussbaum ObjectificationДокумент43 страницыNussbaum ObjectificationSarah DeОценок пока нет

- MIKKOLA, Mari. Beyond Speech Pornography and Analytic Feminist PhilosophyДокумент289 страницMIKKOLA, Mari. Beyond Speech Pornography and Analytic Feminist PhilosophyLucas Santos100% (2)

- Dworkin, Andrea - Right-Wing WomenДокумент249 страницDworkin, Andrea - Right-Wing Womenvidra1709100% (1)

- Feminist Critique of Feminist Critique, Nadine StrossenДокумент93 страницыFeminist Critique of Feminist Critique, Nadine StrossencarlsbaОценок пока нет

- Heartbreak The Political Memoir of A Feminist Militant (Andrea Dworkin)Документ117 страницHeartbreak The Political Memoir of A Feminist Militant (Andrea Dworkin)drkabir100% (1)

- GDI 2015 - Feminist Jurisprudence KДокумент72 страницыGDI 2015 - Feminist Jurisprudence KMichael LiОценок пока нет

- DWORKIN, Andrea - Intercourse PDFДокумент4 страницыDWORKIN, Andrea - Intercourse PDFCarol MariniОценок пока нет

- Pornography Chapter Seven: Whores and the LeftДокумент1 страницаPornography Chapter Seven: Whores and the LeftMirela FonsecaОценок пока нет

- Ice & Fire - Andrea Dworkin PDFДокумент145 страницIce & Fire - Andrea Dworkin PDFТатьяна Керим-Заде100% (1)

- The New Womans Broken Heart - Andrea Dworkin PDFДокумент57 страницThe New Womans Broken Heart - Andrea Dworkin PDFТатьяна Керим-Заде100% (2)

- Pornography As Defamation and DiscriminationДокумент27 страницPornography As Defamation and DiscriminationEstefanía Vela Barba100% (1)

- 23 Quotes From FeministsДокумент2 страницы23 Quotes From Feminists300r100% (1)

- Take Back The Night Women On Pornography (Laura Lederer) (Z-Library)Документ372 страницыTake Back The Night Women On Pornography (Laura Lederer) (Z-Library)cher100% (1)

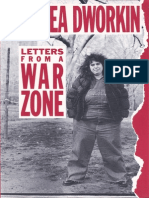

- Letters From A War Zone - Andrea Dworkin PDFДокумент338 страницLetters From A War Zone - Andrea Dworkin PDFТатьяна Керим-ЗадеОценок пока нет

- Feminism, Queer Theory and Sexual CitizenshipДокумент19 страницFeminism, Queer Theory and Sexual CitizenshipIdil Engindeniz ŞahanОценок пока нет

- The Limits of Free Speech, Pornography and The Law: Steven Balmer, JRДокумент17 страницThe Limits of Free Speech, Pornography and The Law: Steven Balmer, JRAbner Casallo TraucoОценок пока нет

- Feminist TheoryДокумент8 страницFeminist TheoryHaley Elizabeth Harrison50% (2)

- AJODA Paper Less Dpi SinglesДокумент100 страницAJODA Paper Less Dpi Singlesmadlib492Оценок пока нет

- Spivak Cornell Et Al - Nussbaum and Her CriticsДокумент6 страницSpivak Cornell Et Al - Nussbaum and Her Criticsjamesbliss0100% (2)

- Our Blood: Prophesies And-Discourses On Sexual Politics 1976Документ140 страницOur Blood: Prophesies And-Discourses On Sexual Politics 1976KuroiTheDevilman100% (1)

- Andrea Dworkin's Radical Feminist Critique of PornographyДокумент8 страницAndrea Dworkin's Radical Feminist Critique of PornographyTrina Nileena BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- Feminist's BooksДокумент12 страницFeminist's Booksheather heather100% (2)

- 30 Womens Rts LRep 543Документ24 страницы30 Womens Rts LRep 543Ayushi TiwariОценок пока нет