Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Political Law Cases

Загружено:

Emer MartinИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Political Law Cases

Загружено:

Emer MartinАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ynot v IAC 148 SCRA 659 Facts: Executive Order No.

626-A prohibited the transportation of carabaos and carabeef from one province to another. The carabaos of petitioner were confiscated for violation of Executive Order No 626-A while he was transporting them from Masbate to Iloilo. Petitioner challenged the constitutionality of Executive Order No. 626-A. The government argued that Executive Order No. 626-A was issued in the exercise of police power to conserve the carabaos that were still fit for farm work or breeding.

Issue: Whether or Not EO No. 626-A is a violation of Substantive Due Process.

Held: The challenged measure is an invalid exercise of police power, because it is not reasonably necessary for the purpose of the law and is unduly oppressive. It is difficult to see how prohibiting the transfer of carabaos from one province to another can prevent their indiscriminate killing. Retaining the carabaos in one province will not prevent their slaughter there. Prohibiting the transfer of carabao beef, after the slaughter of the carabaos, will not prevent the slaughter either.

Lozano V. Martinez 146 SCRA 323 Facts: A motion to quash the charge against the petitioners for violation of the BP 22 was made, contending that no offense was committed, as the statute is unconstitutional. Such motion was denied by the RTC. The petitioners thus elevate the case to the Supreme Court for relief. The Solicitor General, commented that it was premature for the accused to elevate to the Supreme Court the orders denying their motions to quash. However, the Supreme Court finds it justifiable to intervene for the review of lower court's denial of a motion to quash.

Issue: Whether or not BP 22 is constitutional as it is a proper exercise of police power of the State.

Held: The enactment of BP 22 a valid exercise of the police power and is not repugnant to the constitutional inhibition against imprisonment for debt. The offense punished by BP 22 is the act of making and issuing a worthless check or a check that is dishonored upon its presentation for payment. It is not the non-payment of an obligation which the law punishes. The law is not intended or designed to coerce a debtor to pay his debt. The law punishes the act not as an offense against property, but an offense against public order. The thrust of the law is to prohibit, under pain of penal sanctions, the making of worthless checks and putting them in circulation. An act may not be considered by society as inherently wrong, hence, not malum in se but because of the harm that it inflicts on the community, it can be outlawed and criminally punished as malum prohibitum. The state can do this in the exercise of its police powe

Bunting v. Oregon 243 U.S. 426 Facts of the Case A 1913 state law prescribed a 10-hour day for men and women, expanding the law regulating women's hours upheld in Muller v. Oregon. The measure also required time-and-a-half wages for overtime up to 3 hours a day. The State asserted that the law was an appropriate exercise of its police powers. Bunting failed to comply with the overtime regulations of the statute. Issue: Did the law interfere with liberty of contract protected by the Fourteenth Amendment? Held: The Court upheld the decision of the Oregon Supreme Court and found the law constitutional. Relying on the justifications made by the Oregon court and legislature, Justice McKenna dismissed Bunting's contention that the law did nothing to preserve the health of employees. The Court found that the law did not provide an unfair advantage to certain types of employers in the labor market since it regulated the hours of service for workers and not the wages that they earned. Under the Oregon statute, workers and their employers were still free to implement a wage scheme which was agreeable to both of them.

MMDA Vs. Bel-Air Village [328 SCRA 836; G.R. No. 135962; 27 Mar 2000]

Facts: Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), petitioner herein, is a Government Agency tasked with the delivery of basic services in Metro Manila. Bel-Air Village Association (BAVA), respondent herein, received a letter of request from the petitioner to open Neptune Street of Bel-Air Village for the use of the public. The said opening of Neptune Street will be for the safe and convenient movement of persons and to regulate the flow of traffic in Makati City. This was pursuant to MMDA law or Republic Act No. 7924. On the same day, the respondent was appraised that the perimeter wall separating the subdivision and Kalayaan Avenue would be demolished. The respondent, to stop the opening of the said street and demolition of the wall, filed a preliminary injunction and a temporary restraining order. Respondent claimed that the MMDA had no authority to do so and the lower court decided in favor of the Respondent. Petitioner appealed the decision of the lower courts and claimed that it has the authority to open Neptune Street to public traffic because it is an agent of the State that can practice police power in the delivery of basic services in Metro Manila.

Issue: Whether or not the MMDA has the mandate to open Neptune Street to public traffic pursuant to its regulatory and police powers.

Held: The Court held that the MMDA does not have the capacity to exercise police power. Police power is primarily lodged in the National Legislature. However, police power may be delegated to government units. Petitioner herein is a development authority and not a political government unit. Therefore, the MMDA cannot exercise police power because it cannot be delegated to them. It is not a legislative unit of the government. Republic Act No. 7924 does not empower the MMDA to enact ordinances, approve resolutions and appropriate funds for the general welfare of the inhabitants of Manila. There is no syllable in the said act that grants MMDA police power. It is an agency created for the purpose of laying down policies and coordinating with various national government

agencies, peoples organizations, non-governmental organizations and the private sector for the efficient and expeditious delivery of basic services in the vast metropolitan area.

ERMITA-MALATE HOTEL AND MOTEL OPERATORS ASSOCIATION V. CITY OF MANILA 20 SCRA 849 Wednesday, January 21, 2009 Posted by Coffeeholic Writes Labels: Case Digests, Political Law Facts: The principal question in this appeal from a judgment of the lower court in an action for prohibition is whether Ordinance No. Of the City of Manila is violating of due process clause. It was alleged that Sec. 1 of the challenged ordinance is unconstitutional and void for being unreasonable and violate of due process insofar as it would impose P6T fee per annum for first class motels and P4,500 for second class motels, that Sec. 2, prohibiting a person less than 18 years from being accepted in such hotels, motels, lodging houses, tavern or common inn unless accompanied by parents or a lawful guardian and making it unlawful for the owner, manager, keeper or duly authorized representative of such establishments to lease any room or portion thereof more than twice every 24 hours runs counter to due process guaranty for lack of certainty and for its unreasonable, arbitrary and oppressive character.

Issue: Whether or not the ordinance is violative of the due process clause?

Held: A Manila ordinance regulating the operation of hotels, motels and lodging houses is a police measure specifically aimed to safeguards public morals. As such it is immune from any imputation of nullity resting purely on conjecture and unsupported by anything of substance. To hold otherwise would be to unduly restrict and narrow the scope of police power which has been properly characterized as the most essential, insistent and the less limitable of powers extending as it does to all great public needs.

Much discretion is given to municipal corporations in determining the amount of license fees to be imposed for revenue. The mere fact that some individuals in the community may be deprived of their present business or a particular mode of earning a living cannot prevent the exercise of police power.

There is no controlling and precise definition of due process. It furnishes though a standard to which governmental action should conform in order that deprivation of life, liberty or property, in each appropriate case, be valid. The standard of due process which must exist both as a procedural and as substantive requisite to free the challenged ordinance, or any governmental action for that matter, from imputation of legal infirmity is responsiveness to the supremacy of reason, obedience to the dictates of justice. It would be an affront to reason to stigmatize an ordinance enacted precisely to meet what a municipal lawmaking body considers an evil of rather serious proportions as an arbitrary and capricious exercise of authority. What should be deemed unreasonable and what would amount to an abduction of the power to govern is inaction in the face of an admitted deterioration of the state of public morals.

The provision in Ordinance No. 4760 of the City of Manila, making it unlawful for the owner, manager, keeper or duly authorized representative of any hotel, motel, lodging house, tavern or common inn or the like, to lease or rent any room or portion thereof more than twice every 24 hours, with a proviso that in all cases full payment shall be charged, cannot be viewed as a transgression against the command of due process. The prohibition is neither unreasonable nor arbitrary,

because there appears a correspondence between the undeniable existence of an undesirable situation and the legislative attempt at correction. Moreover, every regulation of conduct amounts to curtailment of liberty, which cannot be absolute.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Law of Tort CasesДокумент203 страницыLaw of Tort Caseskuboja_joram100% (2)

- State ResponsibilityДокумент38 страницState ResponsibilityAinnabila Rosdi100% (1)

- HOLLISTER V SOETORO - JOINT MOTION - To Schedule Oral ArgumentДокумент24 страницыHOLLISTER V SOETORO - JOINT MOTION - To Schedule Oral Argumentxx444Оценок пока нет

- People Vs TudtudДокумент2 страницыPeople Vs TudtudjayОценок пока нет

- Consunji Vs Court of Appeals (Case Digest) PDFДокумент2 страницыConsunji Vs Court of Appeals (Case Digest) PDFMTCD100% (1)

- Sample Complaint For Collection For A Sum of MoneyДокумент4 страницыSample Complaint For Collection For A Sum of MoneyMatthew Witt100% (2)

- Hrs. of Baloy vs. CAДокумент1 страницаHrs. of Baloy vs. CAalliah SolitaОценок пока нет

- CSC v. SojorДокумент4 страницыCSC v. SojorKarla Bee100% (1)

- Case No. 69 - Antonio Vs ReyesДокумент1 страницаCase No. 69 - Antonio Vs ReyesMargie Marj GalbanОценок пока нет

- Tamano vs. Ortiz: Block 4Документ2 страницыTamano vs. Ortiz: Block 4Sanjeev J. Sanger100% (1)

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES Vs HENRY T. GOДокумент2 страницыPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES Vs HENRY T. GOCandelaria QuezonОценок пока нет

- COUNTER-AFFIDAVIT (Karen Joy Henderin)Документ4 страницыCOUNTER-AFFIDAVIT (Karen Joy Henderin)Emer MartinОценок пока нет

- Sample Memorandum of AgreementДокумент4 страницыSample Memorandum of AgreementEmer Martin100% (1)

- Dela Cruz vs. Dela Cruz 419 SCRA 648Документ1 страницаDela Cruz vs. Dela Cruz 419 SCRA 648Ash MangueraОценок пока нет

- Termination Letter TagalogДокумент8 страницTermination Letter TagalogGerry MalgapoОценок пока нет

- Certification of No Available Doj RepresentativeДокумент1 страницаCertification of No Available Doj RepresentativeEmer MartinОценок пока нет

- COUNTER-AFFIDAVIT (Andres Apo)Документ2 страницыCOUNTER-AFFIDAVIT (Andres Apo)Emer MartinОценок пока нет

- Court Report PDFДокумент5 страницCourt Report PDFAinnabila RosdiОценок пока нет

- Steps For Driver's License Renewal, Just Make Sure You Bring Your Old Driver'sДокумент1 страницаSteps For Driver's License Renewal, Just Make Sure You Bring Your Old Driver'sEmer MartinОценок пока нет

- 19 SCRA 962 - Business Organization - Corporation Law - Piercing The Veil of Corporate Fiction - Fraud CaseДокумент2 страницы19 SCRA 962 - Business Organization - Corporation Law - Piercing The Veil of Corporate Fiction - Fraud CaseEmer MartinОценок пока нет

- Corpo 3Документ93 страницыCorpo 3Emer MartinОценок пока нет

- Rednotes Legal FormsДокумент26 страницRednotes Legal FormsEmer MartinОценок пока нет

- Kho VS CaДокумент2 страницыKho VS CaEmer MartinОценок пока нет

- Pale Canon 14-22Документ24 страницыPale Canon 14-22Emer MartinОценок пока нет

- Section 14Документ5 страницSection 14Emer MartinОценок пока нет

- Film Development Council Vs Colon Heritage Realty, GR No. 203754Документ12 страницFilm Development Council Vs Colon Heritage Realty, GR No. 203754Gwen Alistaer CanaleОценок пока нет

- Arguments Against Applicant Canned Questions and AnswersДокумент4 страницыArguments Against Applicant Canned Questions and AnswersDILG STA MARIAОценок пока нет

- Pangandaman v. CasarДокумент9 страницPangandaman v. CasarqwertyanonОценок пока нет

- 2019prm KCC Waiver PrintДокумент1 страница2019prm KCC Waiver Printapi-438005956Оценок пока нет

- White Eagle Covid - General DenialДокумент2 страницыWhite Eagle Covid - General DenialAnonymous Pb39klJОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court: Took No PartДокумент34 страницыSupreme Court: Took No PartTeacherEliОценок пока нет

- The Experiences of Civil Lawyers When Studying The Common Law PDFДокумент20 страницThe Experiences of Civil Lawyers When Studying The Common Law PDFKang IpanОценок пока нет

- Case DoctrinesДокумент2 страницыCase DoctrinesCarl IlaganОценок пока нет

- Latp New Resident ChecklistДокумент1 страницаLatp New Resident Checklistapi-22492260Оценок пока нет

- Child Abuse OutlineДокумент9 страницChild Abuse Outlineapi-354584157Оценок пока нет

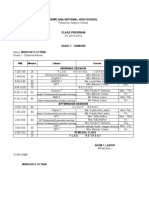

- General Class Program 2019-2020Документ111 страницGeneral Class Program 2019-2020Ian MooneОценок пока нет

- 2018 1 Amr 456Документ11 страниц2018 1 Amr 456SarannRajSomasakaranОценок пока нет

- Labor Law Set 1 Case #003 PLDT Vs NLRCДокумент5 страницLabor Law Set 1 Case #003 PLDT Vs NLRCArnold Christian LozanoОценок пока нет

- Beaulieu v. State of Minnesota - Document No. 4Документ4 страницыBeaulieu v. State of Minnesota - Document No. 4Justia.comОценок пока нет

- 13 Padua V Ranada 390 Scra 663Документ13 страниц13 Padua V Ranada 390 Scra 663sunsetsailor85Оценок пока нет

- Villalon vs. ChanДокумент4 страницыVillalon vs. ChanRocky MagcamitОценок пока нет

- Memorandum SampleДокумент6 страницMemorandum SampleEmrico CabahugОценок пока нет