Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

678 - Ajiss19-1 - Book Reviews - Perspectives On Islamic Law Justice and Society

Загружено:

muzhaffar_razakОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

678 - Ajiss19-1 - Book Reviews - Perspectives On Islamic Law Justice and Society

Загружено:

muzhaffar_razakАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Book Reviews

145

on the fabrication of prophetic traditions. According to I. Goldziher, J. Schacht and G.H.A. Juynboll, these reports were a late artificial elaboration gradually projected back to the Prophets era. These opinions appear to be still admitted by a majority of scholars. However, I have missed some reference to W. Hallaq, H. Motzki, D. Powers, and U. Rubin, who have recently questioned them.

Delfina Serrano Ruano C.S.I.C. Instituto de Filologia, Departamento de Estudios Arabes Madrid, Spain

Perspectives on Islamic Law, Justice and Society

R .S. Khare, ed. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1999. 207 pages. This short, 207 page book is a refreshing overview of Islamic legal principles and new trends within Islamic societies. Though Islamic law has often been viewed as a sluggish monolith, it is actually a rather dynamic field. R.S. Khare has assembled a number of distinguished academics to discuss Islamic law, not as a homogenous entity, but rather in light of the reality: that Islamic law is multi-faceted, varied, highly regional and must be viewed in light of historical changes. Thus, this collection of essays focuses upon the manner in which Islamic law, as an organic law, is constantly reconciling historically changing socio-economic conditions with modernity and technology. The collection is organized in three parts. The first part outlines the concept of Islamic law, formal legal institutions and traditional Islamic scholarship. The second portion of the book focuses on the regionalism of Islamic law and the manner in which the colonial period had a provocative impact upon the evolution and endurance of certain Islamic legal institutions. The final portion of the collection uses two interesting cases in which modernity and technology are problematizing and calling for a fundamental rethinking of seemingly basic principles. The unifying theme of the essays is the manner in which Islamic societies today are dealing with modernity and the manner in which technological advancements and global changes affect Islamic societies and concepts within Islamic law. Though at times the collection seems fragmented due to the different disciplines of the authors, this variety allows for a solid and nuanced understanding of the issues.

146

The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 19:1

The first essay, The Ideal and Real in Islamic Law, by Abdulaziz Sachedina, offers a solid introduction to the Muslim perspective of Shari`ah, from tracing the means by which it was derived to explaining the complexities of public law in Islam, and the epistemological crisis in Muslim societies that must reconcile the manner in which the nation-state system has divided laws into categories of secular and religious. Concerned less with the substance of Islamic law, Sachedina focuses more upon the methodology behind the formation of Islamic law; a process that was bound to an ideal of Medinan society but was also profoundly influenced by practical concerns. While Sachedina concentrates upon the relationship between human beings and God, anthropologist Lawrence Rosen focuses upon the interhuman connections that form Islamic law in his essay Justice in Islamic Culture and Law. Rosen seeks to make the logic of Arab/Islamic legal systems digestible to western audiences, by rooting the logic in the context of the societies from which laws and norms arise. He argues that the concept of intentionality in Arab societies is different from that of western societies due to the context of bargained-for relationships that are central to the definition of the person in Arab culture. Though Rosens approach to Islamic societies is clearly from a position that seeks to bridge a cultural divide, I believe he insists on a far greater divide than actually exists. The contexts of human relationships that Rosen emphasizes as a means to understand the eastern perspective is also central to Anglo-American laws. John Simmons essay, grounded in western legal philosophy, serves as a thoughtful critique of Rosens argument. In Fault, Objectivity, and Classical Islamic Justice, Simmons focuses upon Rosens founding assumptions, commenting on the differences and similarities between Islamic and Anglo-American moral/legal theories. While Rosen contends that Islamic societies (and therefore Islamic law) see fault and responsibility as primarily objective, Simmons believes that, much like the Anglo-American tradition, Islamic law views fault by objective and subjective standards. The second portion of the book, with its focus on Islamic law as a historical phenomenon, explores the effect of the colonial period on Islamic law in India and Algeria. Michael Andersons well-researched article, Legal Scholarship and the Politics of Islam in British India, explores the manner in which colonization affected Islamic legal thought, eventually relegating Islamic law primarily to the realm of personal status issues. He provocatively asserts that colonial administrators may never have changed Islamic legal arrangements quite so profoundly as when they were trying to

Book Reivews

147

preserve them. According to Anderson, Anglo-Mohammadan scholarship focused more upon securing indigenous elite allegiance to the Crown than on a true understanding of Islamic tenets. Thus, the nuances and various forms of logic inherent in South Asian Islamic law as well as the diversity of Islamic schools of thought were obscured by a western paradigm of legal logic. Updating Andersons account to modern India, Tahir Mahmood explores the manner in which Islamic laws have interacted with Indian pubic laws. Freedom of religion, though formally assured, faces several legal and social problems. Mahmood bases his argument on the principle that basic Islamic values agree with the basic philosophy of Indian public law, both being grounded in humanist values. However, since the Indian Constitution needs to serve both Hindu and Muslim religio-moral values, tensions inevitably arise between the freedom of Muslims to practice their faith in a primarily Hindu state. Unfortunately, Mahmood fails to mention egregious and more dramatic tensions within Indian society that reflect vibrant anti-Muslim tensions, such as the destruction of the Barbri mosque by a mob of angry rioters and the failure of the secular states police force to protect Muslim interests. In Changing Conceptions of Marriage in Algerian Personal Status Law, Bettina Dennerlein explores the effect of French colonization on Islamic legal systems and the resultant tension between Islamic and postcolonial secular laws. Basing her work upon a historical study of legal changes between 1963 and 1990, Dennerlein focuses upon family law. She asserts that developments in Algerian personal status laws are best analyzed in light of the social field of family law because it reflects societys basic social structure. In Algerian society one can see how Islamic law, customary law and colonial reforms/secular state law vie for primacy to reflect the values of the people. All reflect different segments of Algerian national identity. The final portion of the book seeks to address new trends in the discourse of Islamic law. In Woman, Half the Man? Crisis of Male Epistemology in Islamic Jurisprudence, Abdulaziz Sachedina tackles a problem that has been plaguing both Muslim and non-Muslim feminists: Muslim womens evidentiary testimony. The fact that the testimony of two women equals that of one man seems diametrically opposed to Islams basic tenets of equality among the sexes. But his article asks a broader question than the technicalities of testimony: Is it possible for a male-dominated religious epistemology to provide an authentic interpretative voice for the female other? When male jurists rule on issues concerning both women and

148

The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 19:1

inter-gender relationships, they make gross assumptions as to the subjective female experience. Sachedina postulates that as a result, the present epistemological crisis in Islamic jurisprudence stems from the absence of female voices in Islamic legal discourse. Sachedinas article is premised upon the notion that whereas the Godhuman relations have remained more or less immutable in Shari>a, the area of inter-human relationships has demanded rethinking and reinterpretation of the normative sources like the Quran and Sunnah to deduce new directives under changed social conditions. Sachedinas essay serves as both a genealogy of Muslim jurists attitudes towards gender and an activist call to Muslim women to be participants in the legal-ethical deliberations of jurists, so as to better redefine their status in modern societies. However, Sachedina fails to address the basic cultural and religious issues that keep women from being active participants in the male-dominated ulama. The final essay, Languages of Change in Islamic Law: Redefining Death in Modernity, by Ebrahim Moosa, explores the intersection of modernity with Islamic juridical semiotics through analysis of the legal opinion of the Academy of Islamic Jurisprudence (AIJ), a transnational organization which functions under the auspices of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC). In this essay, we see themes which have been examined throughout this collection come together. Moosa investigates the historical evolution of Islamic approaches to brain death by taking into account the manner in which colonial rule, the displacement of traditional Muslim education, and technology have shaped the Shari>as approach to the permissible and the impermissible. Moosa posits that this broad dichotomy of extremes permissible and not permissible is in itself faulted. Those open to change, view such changes as permissible on the basis of social necessity or public benefit, whereas traditionalists argue that the consequences of these changes go against the implicit or literal meaning of a religio-juridical text. Moosa employs the example of brainstem death (when a person has suffered irreparable brain injuries and his/her body is artificially ventilated) as a paradigm for this epistemological crisis in the face of changing medical technologies that call into question seemingly basic findings of dead or alive. According to Moosa, the underlying tension arises because [Islamic] legal theory is largely pre-modern in its epistemological and ontological coordinates. Today, most Muslim jurists still employ a pre-modern legal framework. As a result, when challenged by novel ethical problems, modern Muslim legal opinions lack coherence and consistency.

Book Reviews

149

R.S. Khares collection of essays is thought-provoking and well organized as well as containing a diversity of viewpoints. One need not be an expert in Islamic law to understand the essays. Perspectives on Islamic Law, Justice, and Society provides remarkable depth and insight into the theological, historical, sociological and cultural aspects of Islamic law as the historically changing interpretation of a set of divine principles.

Yousra Y. Fazili American University Washington College of Law Washington, DC

Rivers of Fire: The Conflict over Water in the Middle East

Arnon Soffer. Translated by Murray Rosovky and Nina Copaken. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999. 320 pages. Addressing the UNs Second World Water Forum (May 2000), Dr. Kalus Toepfer, executive director of the United Nations Environment Program, took note of the critical importance of water in the search for world peace and prosperity. He noted, water is an indicator of poverty [and] an indicator of environmental stability. While Toepfers speech reflects the growing concern over water, Arnon Soffers Rivers of Fire focuses more closely on the socio-political ramifications of the scarcity of water in the Middle East, and highlights the urgency of international cooperation regarding the global scarcity of water. In his conclusion, he points out US strategic interests in suggesting more involvement of great powers in the problem. Written at the behest of the Israeli government, Soffers introduction immediately raises serious questions for the reader to consider regarding the growing conflicts over water rights. Whether he answers these questions fully in the chapters that follow remains an open question for those who contemplate Rivers of Fire. Soffer asks: Do the regions leaders really perceive that reality has changed and that a transition to a New Middle East is in order? May we truly allow ourselves to be misled with illusions of optimism that sweep all before them? Or should we call out Wait! Nothing has changed. Rivers of Fire was originally published in Hebrew (1992) and appears to shift major blame for the growing conflict over water rights to the Arab

Вам также может понравиться

- Subject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia UniversityДокумент12 страницSubject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia Universitymuzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- R V MohanДокумент10 страницR V Mohanmuzhaffar_razak100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- PP V Kee Ah BahДокумент9 страницPP V Kee Ah Bahmuzhaffar_razak100% (2)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Munah Binti Ali V Public ProsecutorДокумент12 страницMunah Binti Ali V Public Prosecutormuzhaffar_razak100% (3)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Fairus Nizam Bin Shueb V Public ProsecutorДокумент8 страницFairus Nizam Bin Shueb V Public Prosecutormuzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Is Public Nuisance A Tort? Thomas W. MerrillДокумент72 страницыIs Public Nuisance A Tort? Thomas W. Merrillmuzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- Vicarious LiabilityДокумент5 страницVicarious Liabilitymuzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- 1456adpating Legal CulturesДокумент294 страницы1456adpating Legal Culturesmuzhaffar_razak100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Emperor Vs Bhogilal Chimanlal Nanavati On 23 January, 1931Документ2 страницыEmperor Vs Bhogilal Chimanlal Nanavati On 23 January, 1931muzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Legal Analysis of Fraud Vitiating Consent in Sexual Assault CasesДокумент6 страницA Legal Analysis of Fraud Vitiating Consent in Sexual Assault Casesmuzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Peters - Crime and Punishment in Islamic LawДокумент235 страницPeters - Crime and Punishment in Islamic LawMihai IonitaОценок пока нет

- Westlaw Document 02-42-29Документ16 страницWestlaw Document 02-42-29muzhaffar_razakОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Moore, Stanley W. - Three Tactics. The Background in Marx, 1963Документ48 страницMoore, Stanley W. - Three Tactics. The Background in Marx, 1963carlosusassОценок пока нет

- Income Taxation Chapter1Документ50 страницIncome Taxation Chapter1Ja Red100% (1)

- Henry - June - Duenas, Jr. V HRET GR No. 185401Документ3 страницыHenry - June - Duenas, Jr. V HRET GR No. 185401Maddison Yu100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Shehri Story 2006Документ65 страницShehri Story 2006citizensofpakistan100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- G.R. No. 164820 December 8, 2008 VICTORY LINER, INC., Petitioner, PABLO RACE, RespondentДокумент3 страницыG.R. No. 164820 December 8, 2008 VICTORY LINER, INC., Petitioner, PABLO RACE, RespondentWonder WomanОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Chater 2Документ3 страницыChater 2Jaymark FranciscoОценок пока нет

- Secretary of Justice V. LantionДокумент1 страницаSecretary of Justice V. LantionCharlie BartolomeОценок пока нет

- Ancheta Vs AnchetaДокумент20 страницAncheta Vs AnchetaShiva100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- San Miguel V BF HomesДокумент42 страницыSan Miguel V BF HomesCarmela Lucas DietaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- Savigny.-The Jurists of Historical School Have Given A Different TheoryДокумент1 страницаSavigny.-The Jurists of Historical School Have Given A Different TheoryShubham Jain ModiОценок пока нет

- Houston Va LawsuitДокумент10 страницHouston Va Lawsuiteditorial.onlineОценок пока нет

- Dirty Hands: Jean Paul Sartre 1948Документ24 страницыDirty Hands: Jean Paul Sartre 1948SAM Rizvi67% (3)

- Autobiographical Essay ExampleДокумент6 страницAutobiographical Essay ExampletovilasОценок пока нет

- Solutions EditedДокумент2 страницыSolutions Editedpaulinavera100% (1)

- CrimPro - Farrales Vs Camarista Case DigestДокумент3 страницыCrimPro - Farrales Vs Camarista Case DigestDyannah Alexa Marie RamachoОценок пока нет

- P.D 1612-Anti Fencing LawДокумент12 страницP.D 1612-Anti Fencing LawRoemelОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Abhinav Kumar - Gandhi Vs Fanon Notes Part 2Документ6 страницAbhinav Kumar - Gandhi Vs Fanon Notes Part 2me3mori3eОценок пока нет

- Common Letter of Parliamentary, Extra-Parliamentary Parties, & Social Movements of Mauritius 22-05-23 8.00 P.MДокумент2 страницыCommon Letter of Parliamentary, Extra-Parliamentary Parties, & Social Movements of Mauritius 22-05-23 8.00 P.ML'express Maurice100% (1)

- Social, Economic and Political Thought Notes Part II Notes (Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU, J.S. MILL)Документ3 страницыSocial, Economic and Political Thought Notes Part II Notes (Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU, J.S. MILL)simplyhue100% (1)

- Formats Nomination Facility DepositorsДокумент11 страницFormats Nomination Facility DepositorsSimran Jeet SinghОценок пока нет

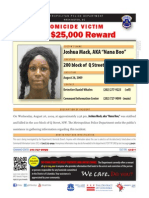

- Mack JoshuaДокумент1 страницаMack JoshuaKimberlyОценок пока нет

- Nyela Dorsey - Butler Causes of WWIДокумент11 страницNyela Dorsey - Butler Causes of WWINyela DorseyОценок пока нет

- KPMG Flash News Vinod Soni and OthersДокумент3 страницыKPMG Flash News Vinod Soni and OthersSundar ChandranОценок пока нет

- International Economic Law SummaryДокумент3 страницыInternational Economic Law SummaryKAYSHA AINAYYA SОценок пока нет

- Colonial Legacy, Women's Rights PDFДокумент22 страницыColonial Legacy, Women's Rights PDFthayaneОценок пока нет

- Robin V HardawayДокумент22 страницыRobin V HardawayJohn Boy75% (4)

- Laws and Social ChangeДокумент12 страницLaws and Social ChangeAbhidhaОценок пока нет

- CH 25 Sec 4 - Reforming The Industrial WorldДокумент7 страницCH 25 Sec 4 - Reforming The Industrial WorldMrEHsieh100% (1)

- Heirs of The Late Nestor Tria vs. Obias, 636 SCRA 91, November 24, 2010Документ25 страницHeirs of The Late Nestor Tria vs. Obias, 636 SCRA 91, November 24, 2010TNVTRLОценок пока нет

- Fstone-Richards@ucsb - Edu: Required Book and EditionДокумент7 страницFstone-Richards@ucsb - Edu: Required Book and EditionClaudia HudsonОценок пока нет