Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cross Cultural Analysis of The Use and Perceptions of Web Based Learning Systems

Загружено:

Minh ToanИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cross Cultural Analysis of The Use and Perceptions of Web Based Learning Systems

Загружено:

Minh ToanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Computers & Education

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/compedu

Cross cultural analysis of the use and perceptions of web Based learning systems

Jorge Arenas-Gaitn a,1, Patricio E. Ramrez-Correa b, *, F. Javier Rondn-Catalua a,1

a b

University of Seville, Dep. Administracin de Empresas y Marketing, Av. Ramon y Cajal 1, 41018 Sevilla, Spain Universidad Catolica del Norte, Escuela de Ingeniera Comercial, Larrondo 1281, 1781421 Coquimbo, Chile

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history: Received 16 June 2010 Received in revised form 4 September 2010 Accepted 27 March 2011 Keywords: Cross-cultural projects Computer-mediated communication Post-secondary education Distance education and telelearning

a b s t r a c t

The main objective of this paper is to examine cultural differences and technology acceptances from students of two universities, one is from a European country: Spain, and the other is in Latin America: Chile. Both of them provide their students with e-learning platforms. The technology acceptance model (TAM) and Hofstedes cultural dimensions are the tools used to measure the acceptance and use of web-based learning platforms and cultural diversity of respondents, respectively. In summary, we can afrm that the sample of tertiary Spanish and Chilean students are culturally different with regard to some of Hofstedes dimensions, but their behavior of acceptance of e-learning technology globally matches according to the TAM model. This study provides relevant implications for on-line courses managers who have tertiary students from different nationalities. 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction Rather than replacing traditional classroom teaching, e-learning complements it and thousands of on-line courses are being offered by universities and colleges world-wide in this way. E-Learning, also known as Web-based learning is dened as an Internet-enabled learning process (Gunasekaran, Mcneil, & Shaul, 2002).It has been crucial to make learning methods become more portable and exible (Zhang & Nunamaker, 2003). And these characteristics are even more important in modern higher education. E-learning adoption by university students is growing at a world-wide level. However, courses completely on-line (without traditional classroom teaching) are less than 5%, and the number of students enrolled in at least a course with relevant on-line contents is ranged between 30 and 50% (OECD, 2005). However, the diverse cultural origins of tertiary students may derive from different perceptions and evaluations of similar e-learning systems. But, given a common purpose and using technology that may minimize cultural differences, is it possible for universities to overcome some of the cultural barriers to tertiary e-learning? What is the inuence of culture on how university students learn and on the technology used to deliver learning solutions in an efcient and effective manner? Designing and implementing e-learning systems in a multi-culture environment is a challenge for tertiary learning institutions. In an increasingly globalized world the presence of students from different nationalities enrolled in the same courses is actually a fact. Furthermore, the growing competence of colleges and universities trying to attract new students will negatively affect the reputation of those educational institutions do not address these multi-cultural issues properly. Another important matter is related to the impact to the learning effectiveness of multi-cultural students of the design and implementation of e-learning systems. The implications of this study point out all these ideas and will help tertiary educational institutions managers to face theses challenges in a more efcient way. As Nathan (2008) points out technical and hard scientic information such as engineering, anatomy, physiology, mathematics, etc., travel well for the simple reason that location and cultural context do not change the basic content of the information and knowledge being presented. But in social sciences the standardization of e-learning could be more difcult because of cultural aspects. Some authors (Raza & Murad, 2008) think that e-learning sets up a new global social opportunity to transcend regional, racial and national prejudices. According to these ideas, a strong controversy about the inuence of cultural differences in e-learning exists. The importance of considering cultural differences of students that use Web-based learning platforms is an incipient research stream. The signicance of this topic deals with the

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 56 51 209 844; fax: 56 51 209 707. E-mail addresses: jarenas@us.es (J. Arenas-Gaitn), patricio.ramirez@ucn.cl (P.E. Ramrez-Correa), rondan@us.es (F. Javier Rondn-Catalua). 1 Tel.: 34 95 455 4427; fax: 34 95 455 6989. 0360-1315/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.03.016

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

1763

necessity of knowing if e-learning platforms should be accepted, used and perceived in the same manner by all students or national differences should have to be taken into account. This work derives from the conuence of three current research lines. The rst, as we argued above, raise with the use of e-learning platforms in higher education from universities around the world. Some recent studies above this topic are Ngai, Poon, and Chan (2007); Blazic, Law, and Arh (2007); Raza, Kausar, and Paul (2007); and Raza and Murad (2008); Ebner, Lienhardt, Rohs, and Meyer (2010); Law, Lee, and Yu (2010); Hourigan and Murray (2010), Paechter, Maier, and Macher (2010). In the second research stream, the theoretical framework that provides technology acceptance model is used as a tool to study adoption and use of e-learning platforms by university students. There is an important number of studies about this subject, such as Saad, Nebebe, and Tan (2007), Van Raaij and Schepers (2008), Zhang, Zhao, and Tan (2008), Chang and Tung (2008), Halawi and McCarthy (2008), Liaw (2008), Liu, Liao, and Pratt (2009) and Park (2009). In the third line of research, the key element that differentiates our work is to add to the two previous views the adoption of a cross-cultural approach. This approach examines similarities and differences caused by national cultures in the adoption of e-learning technology by college students. Although there are studies that have addressed e-learning from a cross cultural approach (Phuong-Mai, Terlouw, and Pilot (2005), Teng (2007), Hannon and DNetto (2007), and Elenurm (2008), there is clearly a lack of jobs that combine the three proposed lines (Grandon, Alshare, & Kwun, 2005). This paper is structured in the following way. Firstly, the research objectives and literature review are presented. Secondly, a model is proposed. Thirdly, analysis and results of the study are exposed. Finally, the discussion and conclusions are explained. 2. Research objective The main objective of this paper is to examine cultural differences and technology acceptances from students of two universities, one from Spain and the other from Chile. Both of them provide their students e-learning platforms. The TAM model (extended with some TAM2 and TAM3 constructs) and Hofstedes cultural dimensions (including the new ones published in 2008) are the tools used to measure the acceptance and use of web-based learning platforms and cultural diversity of respondents, respectively. In order to achieve this main objective two research questions have to be answered. The rst is to contrast if cultural differences between the Spanish and Chilean samples exist. Spain is a European country member of the European Union and Chile is a Latin-American country associated to Mercosur. To do this, the sample was divided into two groups: Spaniards and Chileans. First of all, Hofstedes dimensions were calculated for each subsample. Then an Independent-Samples T Test procedure was applied. The second secondary aim is to compare the same TAM model in both samples trying to study the acceptation of e-learning platforms in both universities. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) path model approach to Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) has been applied to test this second objective. 3. Literature Review In this section three parts are developed. Firstly, a brief literature review about e-learning in higher education is provided. Secondly, Hofstedes cultural dimensions are explained and analyzed. And nally, TAM models and their applications to e-learning are exposed briey. 3.1. E-Learning in higher education E-learning is becoming an increasingly important part of higher education in many different areas of knowledge. According to Tavangarian, Leypold, Nlting, and Rser (2004) E-learning comprises all forms of electronically supported learning and teaching, which are procedural in character and aim to effect the construction of knowledge with reference to individual experience, practice and knowledge of the learner. Information and communication systems, whether networked or not, serve as specic media to implement the learning process. The rst courses over the Web started to emerge in 1995 and there has been a rapid expansion of on-line learning since then. One of the main reasons for the widespread use of on-line learning in many institutions is that most students now have access to the Internet. The University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, Canada, offered its rst credit courses delivered entirely over the Internet to distance education students in 1996. The same year Murray Goldberg developed a software package called WebCT designed to enable Web-based courses to be offered over the Internet (Bates, 2005). In order to support e-learning, various Web-based learning systems have been developed for colleges and universities. Such as the Web Course Homepage System (WebCH), Blackboard Learning System, the System for Multimedia Integrated Learning (Smile) and Web Course Tools (WebCT), are some of the latest waves of technology-based pedagogical tools (Ngai et al., 2007). However, Web-based learning must take into consideration that education has activated a shift from the teaching paradigm to the learning paradigm. As a result, students are becoming more independent from the teacher. Unfortunately, much of the development of Web-based learning is carried out without a true understanding of issues that are proper to Web-based learning (Hadjerrouit, 2006). In general, Internet-based activities have been incorporated into regular face-to-face classes as an added resource, without reducing classroom time, but in many cases teachers have reduced the number of face-to-face classes (Bates, 2005). For lecturers and students, the implications of e-learning are extensive. Increasingly universities must provide quality and exibility to meet the diverse needs of students this will inevitably involve tailoring courses to suit differing educational needs and aspirations. Another implication of virtual learning is the increase of international competition for students by many universities, of distance methods of delivery and of new communication tools. These are very useful mechanisms that facilitate the internationalization of higher education (ONeill, Singh, & ODonoghue, 2004). For this reason there are an increasing number of students of different countries and cultures enrolled in the same courses. This fact brings into consideration the issue of cultural differences in accepting and reacting to new teaching technologies. Major cultural differences have been found in students with regard to traditions of learning and teaching. In many countries, there is a strong tradition of the authoritarian role of teachers and the transmission of information from teachers to students. Thus, teachers need to be aware of language, cultural or epistemological differences of their students, especially in distance classes (Bates, 2005). However, no differences between students from culturally and nearby countries from Central Europe have been found by Blazic et al. (2007) with regard to the assessment of an e-learning portal. Furthermore, e-learning reects the new dynamic response to the needs of a knowledge society

1764

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

and implies freedom and equality to access knowledge beyond cultural and social boundaries (Raza & Murad, 2008). Even Raza et al. (2007) manifest that e-learning can help in creating globally shared information structure which accepts the valid expression of information differences amongst people. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate this topic in more culturally different countries. In this research two different e-learning platforms are analyzed: WebCT (used by the University of Seville in Spain) that is a commercially available system, and Claroline (used by the Catholic University of the North in Chile). WebCT Campus Edition provides a Virtual Course Environment with a complete set of tools for course preparation, delivery, and management. Instructors have all the tools they need to prepare course materials and manage their day-to-day teaching tasks. Claroline is an Open Source E-Learning and E-Working platform allowing teachers to build on-line courses and to manage learning and collaborative activities on the web. Translated into 35 languages, Claroline has a large world-wide users and developers community. 3.2. Hofstedes cultural dimensions Cross-cultural studies have been developing in last decades. Essentially, these articles deal with studying differences in individual behavior caused by national culture. The core of these studies is culture. However, culture is difcult to dene. Based on various denitions of culture, four main characteristics have emerged (Hoecklin, 1995). First, it is a shared system of meaning, a guide that people of a same group follow in order to be able to understand each others events, behaviors and actions. Second, there is no culture absolute, that is, culture is a relative notion: the way one national culture views the world is relative to how another culture views the world. Third, culture is learned, rather than inherited. It is derived from an individuals social environment. Lastly, culture is a collective rather than an individual phenomenon. Within one culture there can be large variations in individual values and behaviors. This research line has been developed from Hofstedes (1980) article. In this work, Hofstede presented the results of his extensive study of national cultures. Based on data from 117,000 IBM employees from 40 different countries, he extracted four dimensions of culture, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. Subsequently, and in collaboration with Bond and a group of Asian scholars, a fth dimension, long term orientation was added to the framework (Hofstede & Bond, 1988). Recently, in collaboration with other authors, Hofstede has proposed an extension of his previous works adding two new dimensions: monumentalism vs. self-effacement and indulgence vs. restraint. A brief description of the seven cultural dimensions is provided according to Hofstede, Hofstede, Minkov, and Vinken (2008) (Table 1): In addition to the measurement scales proposed by Hofstede, the use of values of each dimension obtained by a large number of nations has been the most common method of comparing national cultures used in academic research. These dimensions were published in Hofstede & Bonds (1988) work. Based on this conceptual framework, cross-cultural analysis has been applied in marketing and management for a long time (Magnusson, Wilson, Zdravkovic, Zhou, & Westjohn, 2006), and recently some of it has been applied to technological (Lippert & Volkmar, 2007) and learning scopes (Elenurm, 2008; Shipper, Hoffman, & Rotondo, 2007). For some time, many articles have been showing that cross-cultural variables affect learning. Economides (2008) made a good review of this type of work. Sanchez and Gunawardena (1998) found that Hispanic adult learners showed a strong preference for collaborative over competitive activities. Computer conferencing would be appropriate since it supports group activities (discussion on a topic, problem solving, role playing, etc.). Vogel et al. (2000) found that working together in collaborative teams with students from another study background and country offers much educational value and is highly appreciated. However, Hong Kong students experienced a global team feeling and trust towards their classmates while Dutch students did not. Gunawardena, Nolla, Wilson, Lopez, Ramirez & Megchun (2001) observed that there were differences in perception of on-line group process and development between participants in Mexico and the US. There were signicant differences in perception for the Norming and Performing stages of group development. The groups also differed

Table 1 Hofstedes Cultural Dimensions. Dimension Power Distance Individualism vs. Collectivism Denition Is dened as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a society expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. Individualism stands for a society in which the ties between individuals are loose: people are expected to look after themselves and their immediate family only. Collectivism stands for a society in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in groups, which continue to protect them throughout their lifetime in exchange for unquestioning loyalty Masculinity stands for a society in which social gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life. Femininity stands for a society in which social gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life Is dened as the extent to which the members of institutions and organizations within a society feel threatened by uncertain, unknown, ambiguous, or unstructured situations. Long Term Orientation stands for a society which fosters virtues oriented towards future rewards, in particular adaptation, perseverance and thrift. Short Term Orientation stands for a society which fosters virtues related to the past and present, in particular respect for tradition, preservation of face, and fullling social obligations Indulgence stands for a society which allows relatively free gratication of some desires and feelings, especially those that have to do with leisure, merrymaking with friends, spending, consumption and sex. Its opposite pole, Restraint, stands for a society which controls such gratications, and where people feel less able to enjoy their lives. Monumentalism stands for a society which rewards people who are, metaphorically speaking, like monuments: proud and unchangeable. Its opposite pole, Self-Effacement, stands for a society which rewards humility and exibility. The Monumentalism Index will probably be negatively correlated with the Long Term Orientation Index, but it includes aspects not covered by the latter.

Masculinity vs. Femininity

Uncertainty Avoidance Long Term Orientation vs. Short Term Orientation

Indulgence vs. Restraint

Monumentalism vs. Self-Effacement

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

1765

in their perception of collectivism, low power distance, femininity, and high-context communication. Ramburuth and McCormick (2001) found that Australian and Asian international students differed signicantly in group learning, supporting the notion of Asian students being more collaborative. Chang and Lim (2002) found that culturally heterogeneous (mixed individualistic and collectivist) groups had higher reasoning levels than homogeneous collectivistic groups but lower than individualistic groups. Park (2002) investigated the learning styles of English learners (Armenian, Hong Kong, Korean, Mexican, and Vietnamese) in Californian secondary schools. He found signicant ethnic group differences. Hong Kong, Mexican, and Vietnamese students preferred group learning while Armenian and Korean students did not. Kim and Bonk (2002) found that Korean students were more social and contextually driven on-line while Finnish students were more group-focused. The US and Finnish students spent much time sharing knowledge and resources. Korean students showed a higher level of social interaction behaviors than Finnish or American students, whose social interaction behaviors were almost absent. Phuong-Mai et al. (2005) pointed out that the collectivist mentality of the Confucian heritage culture strongly supports cooperation, guarantees group success and enables the learners best performance in groups. However, not all forms of cooperative learning will surely succeed within a Confucian heritage culture environment. In a study to examine the knowledge transfer and collaboration in distributed teams, Sarker (2005) observed that members of individualistic cultures (US students) transferred/shared more knowledge than those in collectivist cultures (Thai students). The communication style preferred by cultures (high-context vs. low-context) may have a signicant impact on who is viewed as a knowledge transferor within a collaborative group. Thai students seemed to avoid extensive communication about new and difcult concepts with their remote participants. The US students were complaining about the limited and somewhat ineffective communication received from the Thai team members. Teng (2007) found that the US students had developed a better sense of community and closer relationships with their classmates. It was easier for them to make group decisions. They demonstrated more enjoyment in working in groups and showed greater satisfaction with their group performances. They agreed more that they had participated in the group projects to the best of their abilities. Also, they felt that they were more supported by their group members and had known their group members better through this project. On the other hand, Taiwanese students preferred building relationships than working in teams. A divide in the sense of importance of task completion between the two countries was observed. Multi-cultural collaborative learning does not always lead to successful outcomes. In a case study on collaborative learning in distributed US and Japanese teams, Agerup and Bsser (2004) mentioned that based on cultural differences the graduate students initiative to collaborate gradually failed. Instead of a mutual engagement that led to knowledge creation, only the lower level of a web-based coordination was reached. Furthermore, Anakwe, Kessler, and Christensen (1999) examined the impact of cultural differences on potential users receptivity towards distance learning. Findings revealed that an individuals culture affects his or her overall attitude towards distance learning. Specically, individualists motives and communication patterns t to distance learning as a medium of instruction or communication, while collectivists motives and communication patterns turn away from distance learning. Mercado, Parboteeah, and Zhao (2004) evaluate the particular challenges of designing and delivering a web course for an international user group. They integrate the burgeoning literature on on-line communication and distance education with Hofstedes (2001) taxonomy of national cultures. Hannon and DNetto (2007) found that learners from different cultures respond differently to the organizational imperatives and arrangements which are built into on-line learning technologies Grandon et al. (2005) proposed a research model based on TAM to examine factors that inuence students intentions to take on-line courses. To validate the research model, data were collected from college students in the United States and South Korea. For American students, convenience, quality, subjective norm, and perceived ease of use were signicant predictors of students intention. Only quality and subjective norms were signicant factors impacting Korean students intentions. Elenurm (2008) highlights factors supporting and inhibiting cross-cultural synergies between action learning and e-learning. Particularly, Chinese students had greater difculties adapting to the self-managing mode of teamwork than western European students. Power distance helps to explain the normative and cultural need for a hierarchy-based leadership shaped by the Confucian tradition. At the same time, Chinese students were however more systematic and workaholic in their efforts, if their role in the team was clearly specied, than students from southern Europe. One explanation of this may be linked to Asian long term orientation, and uncertainty avoidance, in the knowledge acquisition and transfer context, means that experts are eager to get exact formal descriptions of their tasks. Nathan (2008) shows how cultural differences can have a practical impact on learning methodologies. In this context, the development of global learning platforms based on technology and e-learning is a challenge. For example, WebCT can be used in different cultures and languages. The paper discussed a number of culturally-specic issues that need to be addressed in the design and development process of building a global learning system. Based on the ndings and conclusions of the investigations mentioned above, it can be afrmed that cultural differences affect the development of e-learning. According to Hofstede (1980), there are differences between cultural values of Chilean and Spanish citizens. In this context, Contreras (2003) concluded that cultural differences among Chilean and Spaniards MBA students exist. Based in the previous statement, we propose the following hypotheses: H0a. There are statistically signicant differences between the cultural values of the sample of Chilean and Spanish students. H0b. There are statistically signicant differences between Chilean and Spanish students in the relationships among the constructs of the proposed model in higher education.

3.3. E-Learning & TAM models Proposed by Fred Davis (Davis, 1989), TAM posits that individual behavior intention to use information technology is determined by the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Also, perceived ease of use is directly impacted by perceived usefulness. Since then, several

1766

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

revisions and expansions have developed the original model. The most popular developments have been TAM2 (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000) and TAM3 (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). The literature presents several studies using TAM to assess users acceptance of e-learning technology. In most of these studies, the TAM was extended using factors predictors or moderators, such as: subjective norms (Grandon et al., 2005; Lee, Cho, Gay, Davidson, & Ingraffea, 2003; Park, 2009; Van Raaij & Schepers, 2008; Yuen & Ma, 2008); computer self-efcacy (Chang & Tung, 2008; Grandon et al., 2005; Hayashi, Chen, Ryan, & Wu, 2004; Ong & Lai, 2006; Ong, Lai, & Wang, 2004; Park, 2009; Yuen & Ma, 2008); perceived playfulness (Chen, Chen, Lin, & Yeh, 2007; Roca & Gagn, 2008; Zhang et al., 2008); cognitive absorption (Liu et al., 2009; Saade & Bahli, 2005); system features (Chang & Tung, 2008; Chen et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2009; Park, 2009); computer anxiety (Van Raaij & Schepers, 2008); gender (Ong & Lai, 2006); motivational factors (Park, Lee, & Cheong, 2007; Roca & Gagn, 2008); personal innovativeness (Van Raaij & Schepers, 2008); technical support (Ngai et al., 2007); perceived credibility (Ong et al., 2004); and compatibility (Chang & Tung, 2008). Venkatesh and Bala (2008) proposed job relevance (REL) and result demonstrability (RES) as predictors of TAM in the general context of information systems. Nevertheless, we dont nd in the literature a specic validation of these propositions. The TAM model has been used successfully in the context of e-learning (Saad et al., 2007). In particular, Halawi & McCarthy (2008) suggested that students use e-learning environment (USE) if they perceive it is useful (PU) and easy to use (PEOU). Previously, Ngai et al. (2007) indicated that the perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) are the main factors affecting the attitude of university students to use e-learning (BI). Also, Hayashi et al. (2004) veried that the perceived usefulness (PU) directly affects students intention to continue using e-learning (BI). Considering the importance of a replica in a culturally different sample from those already explored, and based on these previous studies, the following hypotheses are proposed: H1a. PU is positively related to BI in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H1b. PU is positively related to BI in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. H2a. PEOU is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H2b. PEOU is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. H3a. PEOU is positively related to BI in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H3b. PEOU is positively related to BI in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. H4a. BI is positively related to USE in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H4b. BI is positively related to USE in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. Venkatesh and Bala (2008) proposed that job relevance (REL) and result demonstrability (RES) are antecedents of perceived usefulness (PU). On the other hand, the same authors suggested that perception of external control (PCE) is an antecedent of perception of ease of use (PEOU). Considering the importance of a replica in a culturally different sample explored in Venkatesh and Bala (2008), particularly in an elearning environment, the following hypotheses are proposed: H5a. REL is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H5b. REL is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. H6a. RES is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile. H6b. RES is positively related to PU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain. H7a. PCE is positively related to PEOU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Chile.

H7b. PCE is positively related to PEOU in adopting e-learning in higher education in Spain.

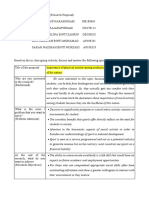

Fig. 1. Proposed model.

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774 Table 2 Hofstedes indices obtained. Power Distance (*) Spain Chile 56.04 52.98 Individualism vs. Collectivism 45.35 46.54 Masculinity vs. Femininity (*) 63.44 66.04 Uncertainty Avoidance 48.23 48.87 Long Term Orientation vs.Short Term Orientation 50.67 50.90 Indulgence 53.1 54.18

1767

Monumentalism (**) 47.61 52.86

** signicant 95%. * signicant 90%.

4. Proposed model According to the aforementioned hypotheses, as can be seen from Fig. 1, the proposed model hypothesizes that job relevance (REL) and result demonstrability (RES) are underlying determinants of perceived usefulness (PU); perception of external control (PCE) is underlying determinant of perceived ease of use (PEOU); PEOU is positively related to PU; Both PU and PEOU inuence students behavioral intentions (BI) to use the e-learning platform; while behavioral intentions, in turn, inuence actual use of the system (USE). The model core proposes that two constructs of beliefs (PU and PEOU) have indirect effects on actual use of the e-learning platform through the mediation of the behavioral intentions to use e-learning systems. Furthermore, external variables including, REL, RES, and PCE have indirect effects on behavioral intentions to use e-learning systems through the mediation of PU and PEOU. 5. Research method 5.1. Scales The measurement scales applied have been widely tested in other investigations. Specically, to measure the TAM constructs the scales proposed by Venkatesh and Bala (2008) have been adapted. Use (USE) was operationalized by asking the respondents, On average, how much time do you spend on Learn On-line each day? (In minutes) . Moreover, to measure the cultural dimensions, Values Survey Module (VSM 08) proposed by Hofstede et al. (2008) is used. The VSM 08 is a 34-item questionnaire developed for comparing culturally inuenced values and sentiments of similar respondents from two or more countries, or sometimes regions within countries. It allows scores to be computed on seven dimensions of national culture. Five of the dimensions measured are described extensively in the work of Geert Hofstede (Hofstede, 2001). They deal with key issues in national societies, known from social anthropology and cross-cultural research. These 5 dimensions have been used plentifully in many studies, showing no problems of reliability and validity. The other two dimensions are based on the work of Michael Minkov (2007). Their authors advise that they are experimental but they expect these 2 new dimensions may reveal aspects of national culture not yet covered in the Hofstede dimensions. Therefore, only the assessment model to measure constructs related to TAM is performed. Appendix A presents the items for each construct. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, except use that is a temporal measure (minutes per week). 5.2. Sample The empirical research is based on a non-probabilistic and self-selection sampling method, therefore it is a convenience sample. Specically, the data was collected in Chile and Spain from a sample of on-line questionnaires from May 14, 2009 to July 15, 2009. The on-

Table 3 Results from the cross-loadings procedure by PLS for Spain. Latent Variables Indicators BI1 BI2 BI3 PCE1 PCE2 PCE3 PEOU1 PEOU2 PEOU3 PEOU4 PU1 PU2 PU3 PU4 REL1 REL2 REL3 RES1 RES2 RES3 USE BI 0.84 0.88 0.80 0.27 0.28 0.36 0.37 0.36 0.32 0.28 0.34 0.22 0.27 0.29 0.16 0.09 0.14 0.43 0.34 0.23 0.17 PCE 0.27 0.31 0.34 0.79 0.85 0.84 0.55 0.51 0.49 0.50 0.35 0.23 0.22 0.26 0.18 0.09 0.11 0.34 0.19 0.20 0.09 PEOU 0.29 0.34 0.39 0.50 0.53 0.53 0.85 0.83 0.87 0.71 0.33 0.21 0.20 0.26 0.25 0.12 0.19 0.41 0.30 0.25 0.10 PU 0.26 0.28 0.30 0.33 0.31 0.16 0.38 0.22 0.22 0.15 0.84 0.86 0.85 0.77 0.46 0.41 0.36 0.30 0.38 0.45 0.29 REL 0.07 0.11 0.18 0.24 0.12 0.01 0.26 0.11 0.15 0.18 0.41 0.40 0.42 0.33 0.92 0.85 0.85 0.16 0.25 0.44 0.34 RES 0.31 0.35 0.35 0.26 0.20 0.27 0.29 0.34 0.35 0.29 0.39 0.43 0.36 0.44 0.40 0.26 0.33 0.70 0.86 0.80 0.18 USE 0.17 0.13 0.12 0.09 0.08 0.05 0.15 0.07 0.01 0.08 0.21 0.32 0.24 0.19 0.29 0.28 0.31 0.10 0.08 0.23 1.00

1768

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

Table 4 Results from the cross-loadings procedure by PLS for Chile. Latent Variables Indicators BI1 BI2 BI3 PCE1 PCE2 PCE3 PEOU1 PEOU2 PEOU3 PEOU4 PU1 PU2 PU3 PU4 REL1 REL2 REL3 RES1 RES2 RES3 USE BI 0.81 0.90 0.84 0.40 0.38 0.35 0.49 0.37 0.41 0.30 0.40 0.43 0.36 0.49 0.43 0.36 0.39 0.44 0.43 0.36 0.31 PCE 0.47 0.41 0.30 0.82 0.80 0.86 0.58 0.57 0.51 0.42 0.46 0.44 0.37 0.41 0.24 0.22 0.24 0.14 0.18 0.11 0.16 PEOU 0.30 0.41 0.47 0.49 0.43 0.59 0.89 0.87 0.89 0.78 0.43 0.48 0.46 0.51 0.33 0.23 0.29 0.23 0.26 0.18 0.22 PU 0.39 0.44 0.40 0.38 0.42 0.40 0.57 0.48 0.45 0.31 0.88 0.87 0.87 0.86 0.29 0.27 0.29 0.26 0.34 0.40 0.24 REL 0.42 0.36 0.35 0.20 0.21 0.23 0.35 0.24 0.31 0.16 0.26 0.26 0.23 0.34 0.89 0.89 0.90 0.46 0.32 0.47 0.11 RES 0.34 0.45 0.39 0.13 0.16 0.12 0.26 0.15 0.26 0.18 0.42 0.30 0.31 0.34 0.50 0.37 0.40 0.85 0.88 0.88 0.11 USE 0.25 0.24 0.30 0.21 0.13 0.08 0.22 0.15 0.22 0.17 0.20 0.28 0.19 0.19 0.15 0.06 0.08 0.06 0.13 0.09 1.00

line questionnaire was sent to students of the Catholic University of the North (Chile) and the University of Seville (Spain) that use e-learning platforms provided by these universities. The exclusion of invalid questionnaires due to duplications or empty elds provided a nal sample size of 352 students, 193 from the Spanish University and 159 from the Chilean. 52.4% of the students are men and the rest women. 52.3% of them are from Spain, 45.4% are from Chile and there are 2.3% of other nationalities: Peruvian, Mexican, Argentinean, from the USA, Polish, Italian, Belgian and Bulgarian. 94.5% of respondents think they are members of the biggest ethnic group in their respective countries. Their average age is 22, they have been studying for 4 years (on average) at the University, and 28% do tasks that impede them going to lectures. The response ratios are 34.6% and 35.33% for the Spanish and Chilean samples, respectively.

5.3. Statistical tools Various statistical tools have been applied in this research. At rst, the sample was divided into two groups: Spain with 183 cases and Chile with 159 cases. First of all, Hofstedes dimensions were calculated for each sub-sample. Then the Independent-Samples T Test procedure was applied (using SPSS software) in order to contrast if cultural differences between the Spanish and Chilean samples exist. After that, the Partial Least Squares (PLS) path model approach to Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied to test the research question (Chin, 1998; Tenenhaus, Vinzi, Chatelin, & Lauro, 2005). Specically, multi-group PLS analysis was used to compare between-group differences. SmartPLS 2.0 M3 software (Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005) was used for measurement models analysis and structural model analysis.

6. Analysis and results Hofstedes indices for both sub-samples are shown in Table 2. Signicant differences exist in 3 of the 7 dimensions (Power Distance, Masculinity vs. Femininity and Monumentalism) applying an independent sample t test. This procedure compares means for two groups of cases Spanish vs. Chilean students. SPSS was the software use for this analysis. These results partially support H0a. A PLS path model is described by two models: (1) a measurement model relating the manifest variables (MVs) to their own latent variables (LVs) and (2) a structural model relating some endogenous LVs to other LVs.

Table 5 Cronbachs a coefcient, composite reliability and AVE. Latent Variables Spain Cronbachs Alpha BI PCE PEOU PU REL RES USE 0.79 0.76 0.83 0.85 0.85 0.70 1.00 Composite Reliability 0.88 0.86 0.89 0.90 0.91 0.83 1.00 AVE 0.70 0.68 0.67 0.69 0.77 0.62 1.00 Chile Cronbachs Alpha 0.81 0.77 0.88 0.90 0.87 0.84 1.00 Composite Reliability 0.89 0.86 0.92 0.93 0.92 0.90 1.00 AVE 0.73 0.68 0.74 0.76 0.80 0.76 1.00

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774 Table 6 Latent Variable Correlations for Spain (diagonal elements are Square Roots of the AVE). Latent Variables BI PCE PEOU PU REL RES USE BI 0.84 0.37 0.41 0.34 0.15 0.40 0.17 PCE 0.82 0.63 0.32 0.15 0.29 0.09 PEOU PU REL RES

1769

USE

0.82 0.31 0.22 0.39 0.10

0.83 0.47 0.49 0.29

0.88 0.38 0.34

0.79 0.18

1.00

6.1. Measurement models analysis Prior to analyzing the structural model, the reliability and validity of the measurement models were measured. The individual reliability was assessed examining the loads (l) or simple correlations of the measures or indicators with their respective LVs (indicators with l ! 0.707 were accepted). Readers that want to know more about the measurement models analysis may see Barclay, Thompson, and Higgins (1995) or Carmines and Zeller (1979). Tables 3 and 4 show the results from the cross-loading procedure for Spain and Chile respectively. The reliability of the LV indicates how rigorous observed variables are measuring the same LV, Cronbachs a coefcient was used as the index of LV reliability (LV with a > 0.7 were accepted). In addition, composite reliability was calculated. The LV convergent validity was assessed by examining the average variance extracted (AVE), see Fornell and Larcker (1981) (AVE > 0.5 were accepted). Table 5 shows Cronbachs a coefcient, composite reliability and AVE by LVs. The LV discriminate validity was tested by analyzing if the square root of the AVE from each LV is greater than the correlations with the rest of the LVs (see Tables 6 and 7). 6.2. Structural model analysis Following the validity and reliability of the measurement model being supported, relationships between constructs were tested. The hypotheses were assessed by examining path coefcients (b) and their signicance levels (b >0.2 were accepted). Bootstrapping with 500 sub-samples was performed to test the statistical signicance of each path coefcient using t-tests. The variance explained (R-square) in the endogenous LV and the regression coefcients signicance (F-test) serve as indicators of the explanatory power of the model. The results of PLS analyses for the Spanish model and the Chilean model are shown in Figs. 2 and 3 respectively. The results support H1a, H1b, H2a, H2b, H3a, H3b, H4a, H4b, H5a, H5b, H6a, H6b, H7a and H7b. In order to view the model across the two countries, a multi-group PLS analysis was conducted by comparing differences in coefcients of the corresponding structural paths (Chin, 2000; Keil et al., 2000). Table 8 shows the results.The results do not support H0b. 7. Discussion The power of globalization and the effect of technology result in the acceptance of e-learning throughout the education system being inevitable (Clegg, Hudson, & Steel, 2003). Globalization is the characteristic that best denes the current environment. It is a complex phenomenon which includes different topics. Two of them can be highlighted. Firstly, the increasing timing of technological change in the eld of communications and information technology (CIT) has made a real revolution. Secondly, due to the increase of contacts between people, companies, institutions and other agents across the planet, globalization has entailed a process of homogenization of many aspects of life: education, consumption pattern, technology, culture. However, nowadays the existence of important cultural differences is patent and this is partly caused by contact multiplication. Cross-cultural studies lay on these ideas. Despite this, there is a lack of cross-cultural research that may help in explaining differences and similarities among students perceptions about online instruction. This work tries to contribute elements that help to reduce such a failure. In this sense, this study follows in the way started by Grandon et al. (2005) and followed by Roca, Chiu, and Martinez (2006) and Lee (2010). They pointed out the acceptance of technology by students based on TAM. And, of course, this is a central element of e-learning. However, this work has two important differences to previous ones. First, in order to analyze cultural differences in the respondents behavior from the two samples, the scale proposed by Hofstede et al. (2008) was applied. This aspect differs from previous work for two reasons: most research simply accepts the values published by Hofstede (1980)

Table 7 Latent Variable Correlations for Chile (diagonal elements are Square Roots of the AVE). Latent Variables BI PCE PEOU PU REL RES USE BI 0.85 0.46 0.47 0.49 0.44 0.46 0.31 PCE 0.82 0.62 0.48 0.26 0.16 0.16 PEOU PU REL RES USE

0.86 0.54 0.32 0.25 0.22

0.87 0.32 0.39 0.24

0.89 0.48 0.11

0.87 0.11

1.00

1770

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

Fig. 2. Spain Model: R Square and Path Estimate (Standard Error) of PLS Analyses.

and Hofstede & Bond (1998); and in the used scale appeared two new dimensions: Monumentalism vs. Self-Effacement and Indulgence versus Restraint. This will ensure the measure of similarities and cultural differences between the samples under study. And nally, based on TAM, this research area is wider than Grandon et al. (2005), Roca et al. (2006) and Lee (2010) because some new constructs from TAM2 and TAM3 and Hofstede have been added. Since the rapid growth of the incorporation of information technologies into learning environments, identifying critical factors related to user acceptance of technology is an important issue (Yi & Hwang, 2003). However, most literature about e-learning has tended to be descriptive and with a focus on technology rather than on theoretical contributions (Nichols, 2003). In this context, different authors indicate that user acceptance is the most important determinant of continuance intentions when using any technology, in particular, the success of an e-learning environment depends to a considerable extent on acceptance and use of the students (Roca & Gagn, 2008; Van Raaij & Schepers, 2008). Although the procedure of identifying intentions of the students and understanding the factors that inuence the beliefs of students in relation to e-learning can help to create mechanisms for attracting more students to adopt this learning environment (Grandon et al., 2005), little research has been done to verify the process of how university students adopt and use e-learning (Park, 2009). Results show cultural differences between the Spanish and Chilean students, however, both samples display a similar behavior with regard to the acceptation of e-leaning platforms. What are the implications of these results for tertiary education managers? First, we note the similarities, but above all, cultural differences that appear between samples of Chilean and Spanish students. Both Hispanic-speaking nationalities have some links based on a shared past. However, Spain is a European country and Chile is an American one. Both are two nations with signicant differences; this is evident in cross-cultural studies. The obtained results are consistent with Hofstede, who pointed out similarities and differences between the two nations. The outcomes are according to Contreras (2003), who found cultural differences between Chilean and Spanish MBA students. In agreement to data, three of the seven Hofstede dimensions are signicantly different (Power Distance, Masculinity vs. Femininity and Monumentalism). It is quite logical not to nd differences for Long Term Orientation vs. Short Term Orientation because this is a dimension created to differentiate oriental cultures. With regard to Uncertainty

Fig. 3. Chile Model: R Square and Path Estimate (Standard Error) of PLS Analyses.

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774 Table 8 Path comparison statistics between Spain and Chile. Paths BI -> USE PCE -> PEOU PEOU -> BI PEOU -> PU PU -> BI REL -> PU RES -> PU Spain 0.1661 0.6298 0.3395 0.11 0.2342 0.3242 0.3219 Chile 0.31 0.6159 0.2856 0.463 0.3309 0.0488 0.253 t-pooled 0.60484616 0.04221354 0.13562768 1.16939694 0.24855508 0.98004029 0.21502603

1771

Signicance level n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s.

Avoidance, Hofstede and Bond (1988) found similar values for Spain and Chile, showing people from these countries having a homogeneous behavior in this topic. With reference to Indulgence versus Restraint, it is a new dimension that Hofstede et al. (2008) has incorporated recently and there are no studies published about this construct. Nevertheless, the results obtained for Individualism vs. Collectivism are surprising because in our study this dimension is quite similar in both countries, but Hofstede and Bond (1988) found differences. According to this, tertiary education institutions have to consider that cultural differences in students exist even between, a priori, similar cultures. We can afrm free from doubt that students from more culturally different countries will show bigger differences. This implies that educational institutions have to make an effort in order to adapt their learning systems to this ever-increasing fact if they want to possess a good positioning in this market. At the same time, globalization is standardizing some behaviors, especially among the youth and with regard to new technologies. The results of this work reveal that both samples of students do not show a different technology acceptation model of e-learning platforms. In spite of the cultural differences, e-learning platforms are perceived similarly between both samples. This is an important fact for educational institution managers because this part of learning can be standardized and do not need to be adapted.

8. Conclusions The main objective of this paper is to examine cultural differences and technology acceptances from tertiary students from Spain and Chile using e-learning platforms. In order to achieve this main objective two research questions have to be answered. The rst is to contrast if cultural differences between the Spanish and Chilean samples exist. According to our result, the rst research question is answered in this way: there are signicant cultural differences between both samples of students according to Hofstedes dimensions. In this sense, some reections can be mentioned. On the one hand, one of the key differentiators of this work is the application of the new Hofstede et al. (2008) scale to a sample of Spanish and Chileans tertiary students. Most of the research being conducted within the framework of cross-cultural studies, just taking the scores obtained by Hofstede, or any of the other theoretical frameworks that exist: Trompenaar (1993), Schwartz (1999) or GLOBE (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman & Gupta, 2004). We have decided to adopt the proposal of Hofstede et al. (2008) due to the appearance of two new dimensions (Monumentalism vs. Self-Effacement and Indulgence versus Restraint); there are not available reference scores for these dimensions yet. In this sense, this paper presents one of the rst contributions presenting scores for these new dimensions in Spain and Chile. Moreover, as was gathered in the literature review, the cross-cultural research takes mainly as a framework Anglo-Saxon countries (USA or UK) or Asian (China). There is a clear lack of research on other geographical areas. Our work is a contribution in this issue, addressing the differences between European and other Latin American nation, both of Hispanic speakers. The second research question is to compare the same TAM model in both samples trying to study the acceptation of e-learning platforms in both types of students. According to the results obtained from Smart PLS, there are some important noticeable implications. The most important one is that there are no signicant differences between the sample of Chilean and Spanish students in every relationship of the TAM model. The general behavior in accepting e-learning platforms is quite similar for both sub-samples. With regard to on-line learning, the effects of globalization on the homogenization of tertiary students are perhaps stronger than in other types of population. University students use new technologies more frequently than other types of populations, and especially e-learning platforms because in many subjects they have to employ them compulsorily. However, the strength of the relationships among constructs differs to some extent in both samples. In both groups the strongest link is between perception of external control and perceived ease of use. But the second strongest one is between perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness for Chileans and between perceived ease of use and behavioral intention for Spaniards. There are some other differences in the relationships between both models but they are not statistically signicant. According to the previous results and answering the second research question, the acceptance of e-learning platforms for both samples of students is similar, in spite of some minor differences. In summary, we can afrm that the samples of tertiary Spanish and Chilean students are culturally different with regard to some of Hofstedes dimensions, but their behavior of acceptance of e-learning technology matches globally according to the TAM model. Finally, it is advisable to set out some limitations. Firstly, the model does not include all the TAM 3 variables. We recommend that future research could include all of them. Also, it is necessary to validate and generalize the results in future investigations. Furthermore, we must point out that the majority of individuals who participated were Spanish-speaking. The sample size did not enable us to make generalizations, and it may not hold for different nationalities. To ensure the validity and reliability of the scale proposed by Hofstede et al. (2008) samples of ten different countries at least are necessary, with fty individuals each sub-sample. We could not reach this kind of samples. Similarly, it would be interesting to include Measurement Equivalence across test samples in future research.

1772

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

Appendix A; Items for constructs

TAM CONSTRUCTS Itemsa Behavioral Intentions(BI) BI1 BI2 BI3 Perception of External Control (PCE) PCE1 PCE2 PCE3 Perceived ease of use (PEOU) PEOU1 PEOU2 PEOU3 PEOU4 Perceived Usefulness(PU) PU1 PU2 PU3 PU4 Job Relevance (REL) REL1 REL2 REL3 Result Demonstrability (RES) RES1 RES2 RES3 USE USE

a

Assuming I had access to Learn On-line, I intend to use it Given that I had access to Learn On-line, I predict that I would use it I plan to use Learn On-line in the next months I have control over using the system I have the resources necessary to use the system Given the resources, opportunities and knowledge it takes to use the system, it is easy for me to use the system My interaction with Learn On-line is clear and understandable Interacting with Learn On-line does not require a lot of my mental effort I nd Learn On-line to be easy to use I nd it easy to get Learn On-line to do what I want it to do Using Learn On-line improves my performance in my studies Using Learn On-line in my studies increases my productivity Using Learn On-line enhances my effectiveness in my studies I nd Learn On-line to be useful in my job/studies In my studies, usage of Learn On-line is important In my studies, usage of Learn On-line is relevant The use of Learn On-line is pertinent to my various study-related tasks I have no difculty telling others about the results of using Learn On-line I believe I could communicate to others the consequences of using Learn On-line The results of using Learn On-line are apparent to me On average, how much time do you spend on Learn On-line each day? (In minutes)

All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

Cultural dimensions Itemsa m01 m02 m03 m04 m05 m06 m07 m08 m09 m10 m11 m12 m13 m14 m15 m16 m17 m18 m19 m20 m21 m22 m23 m24 m25 m26 m27 m28 Cultural Dimension Individualism Index (IDV) In choosing an ideal job, how important would it be to you to . 01. have sufcient time for your personal or home life 02. have a boss (direct superior) you can respect 03. get recognition for good performance 04. have security of employment 05. have pleasant people to work with 06. do work that is interesting 07. be consulted by your boss in decisions involving your work 08. live in a desirable area 09. have a job respected by your family and friends 10. have chances for promotion In your private life, how important is each of the following to you . 11. keeping time free for fun 12. moderation: having few desires 13. being generous to other people 14. modesty: looking small, not big 15. If there is something expensive you really want to buy but you do not have enough money . always save before buying 16. How often do you feel nervous or tense? 17. Are you a happy person? 18. Are you the same person at work (or at school if youre a student) and at home? 19. Do other people or circumstances ever prevent you from doing what you really want to? 20. All in all, how would you describe your state of health these days? 21. How important is religion in your life ? 22. How proud are you to be a citizen of your country? 23. How often, in your experience, are subordinates afraid to contradict their boss (or students their teacher?) To what extent do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements? 24. One can be a good manager without having a precise answer to every question that a subordinate may raise about his or her work 25. Persistent efforts are the surest way to results 26. An organization structure in which certain subordinates have two bosses should be avoided at all cost 27. A companys or organizations rules should not be broken - not even when the employee thinks breaking the rule would be in the organizations best interest 28. We should honour our heroes from the past Index formulab IDV 35(m04 m01) 35(m09 m06) C(ic)

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

1773

Indulgence versus Restraint Index (IVR) Long Term Orientation Index (LTO) Masculinity Index (MAS) Monumentalism Index (MON) Power Distance Index (PDI) Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

a b

IVR 35(m12 m11) 40(m19 m17) C(ir) LTO 40(m18 m15) 25(m28 m25) C(ls) MAS 35(m05 m03) 35(m08 m10) C(mf) MON 35(m14 m13) 25(m22 m21) C(mo) PDI 35(m07 m02) 25(m23 m26) C(pd) UAI 40(m20 - m16) 25(m24 m27) C(ua)

All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. C is a constant (positive or negative) that depends on the nature of the samples.

References

Agerup, K., & Bsser, M. (2004). A case study on collaborative learning in distributed, cross-cultural teams. Paper presented at International Conference on Engineering Education. Gainesville: Florida. Anakwe, U. P., Kessler, E. H., & Christensen, E. W. (1999). Distance learning and cultural diversity: potential users perspective. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 7(3), 224243. Barclay, D., Thompson, R., & Higgins, C. H. (1995). The partial least square (PLS) approach to Causal modeling: personal computer adoption and use as an Illustration. Technology Studies, 22, 285309. Bates, A. W. (2005). Technology, E-learning and distance education (2nd ed.). Routledge. Blazic, B. J., Law, E. L. C., & Arh, T. (2007). An assessment of the usability of an Internet-based education system in a cross-cultural environment: the case of the Interreg cross border program in Central Europe. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(1), 6675. Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences.7017, Beverly Hills. Chang, S., & Tung, F. (2008). An empirical investigation of students behavioral intentions to use the on-line learning course websites. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(1), 7183. Chang, T., & Lim, J. (2002). Cross-cultural communication and social presence in asynchronous learning processes. e-Service Journal, 1(3), 83105. Chen, Y., Chen, C., Lin, Y., & Yeh, R. (2007). Predicting college student use of E-Learning systems: An Attempt to Extend technology acceptance model. PACIS 2007 Proceedings. Paper 121. Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In George A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Chin, W. W. (2000). Frequently Asked questions Partial least squares & PLS-Graph. Home Page.[On-line]. Available at: http://disc-nt.cba.uh.edu/chin/plsfaq.htm. Clegg, S., Hudson, A., & Steel, J. (2003). The emperors new clothes: globalization and e-learning in higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 24(1), 3953. Contreras J.L. (2003). The impact of MBA education on cultural convergence: A study of Chile, Spain, and the United States. Doctoral Dissertation from Nova Southeastern University (USA). Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319340. Ebner, M., Lienhardt, C., Rohs, M., & Meyer, I. (2010). Microblogs in Higher Education - A chance to facilitate informal and process-oriented learning? Computers & Education, 55(1), 92100. Economides, A. A. (2008). Culture-aware collaborative learning. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 2(4), 243267. Elenurm, T. (2008). Applying cross-cultural student teams for supporting international networking of Estonian enterprises. Baltic Journal of Management, 3(2), 145158. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 3950. Grandon, E. E., Alshare, K., & Kwun, O. (2005). Factors inuencing student intention to adopt on-line classes: A cross-cultural study. Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges. http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/1050000/1047853/p46-grandon.pdf? key11047853&key24453844521&collGUIDE&dlGUIDE&CFID55770397&CFTOKEN31674932 (accessed Oct, 2, 2009). Gunasekaran, A., Mcneil, R. D., & Shaul, D. (2002). E-learning: research and applications. Industrial and Commercial Training, 34(2), 4453. Gunawardena, C., Nolla, P., Wilson, P., Lopez, J., Ramirez-Angel, N., & Megchun-Alpizar, R. (2001). A cross-cultural study of group process and development in on-line conferences. Distance Education, 22(1), 85110. Hadjerrouit, S. (2006). Creating Web-based learning systems: an evolutionary development methodology. In Proceedings of the 2006 informing science and IT education Joint Conference (pp. 119144), Saldford, UK. Halawi, L., & McCarthy, R. (2008). Measuring students perceptions of blackboard using the technology acceptance model: a PLS approach. Issues in Information Systems, 9(2), 95102. Hannon, J., & DNetto, B. (2007). Cultural diversity online: student engagement with learning technologies. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(5), 418432. Hayashi, A., Chen, C., Ryan, T., & Wu, J. (2004). The role of social presence and moderating role of computer self-efcacy in predicting the continuance usage of e-learning systems. Journal of Information Systems Education, 15(2), 139154. Hoecklin, L. (1995). Managing cultural Differences: Strategies for competitive Advantage. Cambridge, MA: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company. Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. H. (1988). The confucius connection: from cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4), 421. Hofstede, G. (1980). Cultures Consequences: International differences in work-related values. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., Minkov, M., & Vinken, H. (2008). Announcing a new version of the values Survey Module: The VSM 08. Retrieved September 12, 2009, Available at: http://stuwww.uvt.nl/wcsmeets/VSM08.html. Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures Consequences, comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and Organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications. Hourigan, T., & Murray, L. (2010). Using blogs to help language students to develop reective learning strategies: towards a pedagogical framework. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(2), 209225. House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership and Organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Keil, M., Tan, B. C. Y., Wei, K. K., Saarinen, T., Tuunainen, V., & Wassenaar, A. (2000). A cross-cultural study on Escalation of Commitment behavior in software projects. MIS Quarterly, 24(2), 299325. Kim, K. J., & Bonk, C. J. (2002). Cross-cultural comparisons of online collaboration. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, 8(1). available at www.mcmc.indiana.edu/ vol8/issue1/kimandbonk.html (accessed May 15, 2008). Law, K. M. Y., Lee, V. C. S., & Yu, Y. T. (2010). Learning motivation in e-learning facilitated computer programming courses. Computers & Education, 55(1), 218228. Lee, M. C. (2010). Explaining and predicting users continuance intention toward e-learning: an extension of the expectation-conrmation model. Computers & Education, 54(2), 506516. Lee, J.-S., Cho, H., Gay, G., Davidson, B., & Ingraffea, A. (2003). Technology acceptance and social networking in distance learning. Educational Technology & Society, 6(2), 5061. Liaw, S.-S. (2008). Investigating students perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: a case study of the Blackboard system. Computers & Education, 51(2), 864873. Lippert, S. A., & Volkmar, J. A. (2007). Cultural effects on technology performance and Utilization: a comparison of U.S. and Canadian users. Journal of Global Information Management, 15(2), 5690. Liu, S., Liao, H., & Pratt, J. A. (2009). Impact of media richness and ow on e-learning technology acceptance. Computers & Education, 52(3), 599607. Magnusson, P., Wilson, R. T., Zdravkovic, S., Zhou, J. X., & Westjohn, S. A. (2006). Breaking through the cultural clutter; A comparative assessment of multiple cultural and institutional frameworks. International Marketing Review, 25(2), 183201. Mercado, S. K., Parboteeah, P., & Zhao, Y. (2004). On-line course design and delivery: cross-national considerations. Strategic Change., 13(4), 183192. Minkov, M. (2007). What makes us different and similar: A New Interpretation of the world values Survey and other cross-cultural data. Soa, Bulgaria: Klasika I Stil. Nathan, P. E. (2008). Global organizations and e-learning: Leveraging adult learning in different cultures. Performance Improvement, 47(6), 1824. Ngai, E. W. T., Poon, J. K. L., & Chan, Y. H. C. (2007). Empirical examination of the adoption on WebCT using TAM. Computers & Education, 48, 250267. Nichols, M. (2003). A theory for eLearning. Educational Technology & Society, 6(2), 110, 20.

1774

J. Arenas-Gaitn et al. / Computers & Education 57 (2011) 17621774

OECD. (2005). E-learning in tertiary Education: Where do we Stand? Paris: OECD. ONeill, K., Singh, G., & ODonoghue, J. (2004). Implementing eLearning Programmes for higher education: a review of the literature. Journal of Information Technology Education, 3, 313323. Ong, C. S., & Lai, J. Y. (2006). Gender differences in perceptions and relationships among dominants of e-learning acceptance. Computers in Human Behaviour, 22(5), 816829. Ong, C. S., Lai, J. Y., & Wang, Y. S. (2004). Factors affecting engineers acceptance of asynchronous e-learning systems in high-tech companies. Information & Management, 41(6), 795804. Paechter, M., Maier, B., & Macher, D. (2010). Students expectations of, and experiences in e-learning: their relation to learning achievements and course satisfaction. Computers & Education, 54(1), 222229. Park, C. C. (2002). Cross-cultural differences in learning styles of secondary English learners. Bilingual Research Journal, 26(2), 213229. Park, N., Lee, K. M., & Cheong, P. H. (2007). University instructors acceptance of electronic courseware: an application of the technology acceptance model. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1). article 9. Park, S. Y. (2009). An Analysis of the Technology Acceptance Model in Understanding University Students Behavioral Intention to Use e-Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 12(3), 150162. Phuong-Mai, N., Terlouw, C., & Pilot, A. (2005). Cooperative learning vs Confucian heritage cultures collectivism: confrontation to reveal some cultural conicts and mismatch. Asian Europe Journal, 3(3), 403419. Ramburuth, P., & McCormick, J. (2001). Learning diversity in higher education: a comparative study of Asian international and Australian students. Higher Education, 32, 333350. Raza, A., Kausar, R., & Paul, D. (2007). The social democratization of knowledge: some critical reections on e-learning. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 1(1), 6474. Raza, A., & Murad, H. S. (2008). Knowledge democracy and the implications to information access. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 2(1), 3746. Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, A. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0 (M3). Hamburg. http://www.smartpls.de. Roca, J. C., Chiu, C. M., & Martinez, F. J. (2006). Understanding e-learning continuance intention: an extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(8), 683696. Roca, J. C., & Gagn, M. (2008). Understanding e-learning continuance intention in the workplace: a self-determination theory perspective. Computers In Human Behavior., 24(4), 15851604. Saade, R., & Bahli, B. (2005). The impact of cognitive absorption on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in on-line learning: an extension of the technology acceptance model. Information Management, 42, 317327. Saad, R. G., Nebebe, F., & Tan, W. (2007). Viability of the technology acceptance model in multimedia learning environments: comparative study. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 37, 175184. Sanchez, I., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1998). Understanding and supporting the culturally diverse distance learner. In C. C. Gibson (Ed.), Distance learners in higher education (pp. 4764). Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing. Sarker, S. (2005). Knowledge transfer and collaboration in distributed US-Thai teams. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, 10(4). article 15, available at www.jcmc. indiana.edu/vol10/issue4/sarker.html. Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48, 2347. Shipper, F., Hoffman, R. C., & Rotondo, D. M. (2007). Does the 360 Feedback process create Actionable knowledge Equally across cultures? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6(1), 3350. Tavangarian, D., Leypold, M., Nlting, K., & Rser, M. (2004). Is e-learning the Solution for Individual Learning? Journal of e-learning, 2(2), 273280. Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y.-M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 48, 159205. Teng, L. Y. W. (2007). Collaborating and communicating online: a cross-bordered intercultural project between Taiwan and the US. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 13. available at www.immi.se/intercultural/nr13/teng-2.htm (accessed May, 15, 2008). Trompenaars, F. (1993). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business. London: The Economist Books. Van Raaij, E. M., & Schepers, J. J. L. (2008). The acceptance and use of a virtual learning environment in China. Computers and Education, 50(3), 838852. Venkatesh, V., & Bala, H. (2008). Technology acceptance model 3 and a research Agenda on Interventions. Decision Sciences, 39(2), 273315. Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four Longitudinal eld studies. Management Science, 46, 186220. Vogel, D., Van Genuchten, M., Lou, D., Verveen, S., Van Eekhout, M., & Adams, T. (2000). Distributed experiential learning: the Hong Kong-Netherlands project. InProceedings 33rd Hawaii international Conference on system sciences, 1 (pp. 1052). IEEE. Yi, M., & Hwang, Y. (2003). Predicting the use of web-based information systems: self-efcacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59, 431449. Yuen, A. H. K., & Ma, W. W. K. (2008). Exploring teacher acceptance of e-learning technology. Asia-Pacic Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 229243. Zhang, D., & Nunamaker, J. F. (2003). Powering e-learning in the new millennium: an overview of e-learning and enabling technology. Information Systems Frontiers, 5(2), 207218. Zhang, S., Zhao, J., & Tan, W. (2008). Extending TAM for online learning systems: an Intrinsic motivation perspective. Tsinghua Science & Technology, 13(3), 312317.

Вам также может понравиться

- Chapter II (IForeign, Local, Synthesis)Документ11 страницChapter II (IForeign, Local, Synthesis)Ermercado60% (20)

- s10639 019 09886 3 PDFДокумент24 страницыs10639 019 09886 3 PDFKokak DelightsОценок пока нет

- Information Technology Tools Analysis in Quantitative Courses of IT-Management (Case Study: M.Sc. - Tehran University)Документ10 страницInformation Technology Tools Analysis in Quantitative Courses of IT-Management (Case Study: M.Sc. - Tehran University)Andy Poe M ArizalaОценок пока нет

- Chapter - 2 Review of LiteratureДокумент57 страницChapter - 2 Review of LiteraturePreya Muhil ArasuОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Technology in SchoolsДокумент8 страницLiterature Review On Technology in Schoolsc5eakf6z100% (1)

- E-Learning in Iran As A Developing Country: Challenges Ahead and Possible SolutionsДокумент8 страницE-Learning in Iran As A Developing Country: Challenges Ahead and Possible Solutionsmasoud5912Оценок пока нет

- Writing Web Logs in The ESL ClassroomДокумент26 страницWriting Web Logs in The ESL ClassroomAbdul FattahОценок пока нет

- The Brief & Expansive History (And Future) of The MOOC - Why Two DДокумент24 страницыThe Brief & Expansive History (And Future) of The MOOC - Why Two DSanju SahaОценок пока нет

- Attitude Towards E-Learning - The Case of Mauritian Students in Public TeisДокумент16 страницAttitude Towards E-Learning - The Case of Mauritian Students in Public TeisGlobal Research and Development ServicesОценок пока нет

- GroupworkДокумент12 страницGroupworkapi-280162162Оценок пока нет

- Latifah Abdol Latif Ramli Bahroom NG Man San Ahmad Izanee Awang and Nik Najib Nik Abdul RahmanДокумент12 страницLatifah Abdol Latif Ramli Bahroom NG Man San Ahmad Izanee Awang and Nik Najib Nik Abdul RahmanVaishnavi SindhuОценок пока нет

- Meeting The - Digital Natives - Understanding The Acceptance of Technology in Classrooms - Documento - Gale Academic OneFileДокумент15 страницMeeting The - Digital Natives - Understanding The Acceptance of Technology in Classrooms - Documento - Gale Academic OneFileFabiano SantosОценок пока нет

- CcsДокумент10 страницCcsjudithmwatetaОценок пока нет

- R - Schulte and Kraemer - Impact of New Technologies On Distance Learning StudentsДокумент14 страницR - Schulte and Kraemer - Impact of New Technologies On Distance Learning StudentsMartinОценок пока нет

- Students Perception EL TeckДокумент6 страницStudents Perception EL TeckRizky AjaОценок пока нет

- Journal of Information Techology For Teacher EducationДокумент11 страницJournal of Information Techology For Teacher EducationAhmad RizalОценок пока нет

- Barriers For Females To Pursue Stem Careers and Studies at Higher Education Institutions (Hei) - A Closer Look at Academic LiteratureДокумент23 страницыBarriers For Females To Pursue Stem Careers and Studies at Higher Education Institutions (Hei) - A Closer Look at Academic LiteratureijcsesОценок пока нет

- Njala University Department of Physics and Computer ScienceДокумент5 страницNjala University Department of Physics and Computer ScienceAlhaji Daramy0% (1)

- Literature Review About Ict in EducationДокумент5 страницLiterature Review About Ict in Educationgjosukwgf100% (1)

- E-Learning Focus of The ChapterДокумент10 страницE-Learning Focus of The ChapterGeorge MaherОценок пока нет

- eLearningChapter PreprintДокумент23 страницыeLearningChapter Preprintthaiduong292Оценок пока нет

- The Impact of E-Learning On University Students AДокумент9 страницThe Impact of E-Learning On University Students AKevin John BarrunОценок пока нет

- Learning Analytics To Understand Cultural Impacts On Technology Enhanced LearningДокумент8 страницLearning Analytics To Understand Cultural Impacts On Technology Enhanced LearningVianey Sánchez FigueroaОценок пока нет

- Collaborative International Education: Reaching Across BordersДокумент12 страницCollaborative International Education: Reaching Across BordersHANIZAWATI MAHATОценок пока нет

- Technology, Demographic Characteristics and E Learning Acceptance A Conceptual Model Based On Extended Technology Acceptance ModelДокумент18 страницTechnology, Demographic Characteristics and E Learning Acceptance A Conceptual Model Based On Extended Technology Acceptance ModelRISKA PARIDAОценок пока нет

- Modern Distance Learning Technologies in Higher Education Introduction Problems 5542Документ8 страницModern Distance Learning Technologies in Higher Education Introduction Problems 5542sally mendozaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Group 1Документ12 страницChapter 1 Group 1Bernadette FalcesoОценок пока нет

- 1 PDFДокумент18 страниц1 PDFDũng LêОценок пока нет

- Ijtel 2020 107986Документ27 страницIjtel 2020 107986pn996888Оценок пока нет

- Sciencedirect: Attitudes of Undergraduate Students To The Use of Ict in EducationДокумент7 страницSciencedirect: Attitudes of Undergraduate Students To The Use of Ict in EducationDaniel Z JucaОценок пока нет

- Does Computer Use Matter? The Influence of Computer Usage On Eighth-Grade Students' Mathematics ReasoningДокумент23 страницыDoes Computer Use Matter? The Influence of Computer Usage On Eighth-Grade Students' Mathematics Reasoninglynser chuaОценок пока нет

- 8 Krishnakumar.R Final PaperДокумент6 страниц8 Krishnakumar.R Final PaperiisteОценок пока нет

- E-Learning: The Student Experience: Jennifer Gilbert, Susan Morton and Jennifer RowleyДокумент14 страницE-Learning: The Student Experience: Jennifer Gilbert, Susan Morton and Jennifer RowleyNurul Amira AmiruddinОценок пока нет

- EJEL Volume 13 Issue 5Документ116 страницEJEL Volume 13 Issue 5Mancillas Aguayo ManuelОценок пока нет

- Paper 22Документ5 страницPaper 22Editorijer IjerОценок пока нет

- Respecting The Human Needs of Students in The Development of E-LearningДокумент14 страницRespecting The Human Needs of Students in The Development of E-LearningDanisRSwastikaОценок пока нет

- Literature Review Technology in EducationДокумент8 страницLiterature Review Technology in Educationeryhlxwgf100% (1)

- 110779-Article Text-305528-1-10-20141211Документ13 страниц110779-Article Text-305528-1-10-20141211Kibet KiptooОценок пока нет

- ETEC 500 - Article Critique #3Документ7 страницETEC 500 - Article Critique #3Camille MaydonikОценок пока нет

- Chapter II IForeign Local SynthesisДокумент10 страницChapter II IForeign Local SynthesisYnrakaela Delos ReyesОценок пока нет

- Online Education and Its Effective Practice: A Research ReviewДокумент34 страницыOnline Education and Its Effective Practice: A Research ReviewMarvel Tating50% (2)

- Literature Research - Cabalida-SantosДокумент7 страницLiterature Research - Cabalida-SantosJeralyn CABALIDAОценок пока нет

- Development and Evaluation of Cross Cultural Distance Learning ProgramДокумент6 страницDevelopment and Evaluation of Cross Cultural Distance Learning ProgramKnowledge PlatformОценок пока нет

- The E-Generation: The Use of Technology For Foreign Language LearningДокумент12 страницThe E-Generation: The Use of Technology For Foreign Language LearningÁlvaro RubioОценок пока нет