Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Rizals Last Hours

Загружено:

geejeiИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Rizals Last Hours

Загружено:

geejeiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

After the kangaroo trial, Rizal was escorted to his cell in Fort Santiago to make use of his remaining

time. His last 24 hours was his busiest life as if trying to meet the deadline. Last hours of Rizal. At 6:00 A.M., December 29, 1896, Captain Rafael Dominguez, read the death sentence to Rizal to be shot at the back by a firing squad at 7:00 A.M. in Bagumbayan. At 7:00 A.M., an hour after the reading of the death sentence, Rizal was transferred to the Prison Chapel. His first visitors were Father Miguel Saderra Mata and Father Luis Viza. At 7:15 A.M., Father Saderra left. Father Viza handed over the Sacred Heart of Jesus carved by Rizal in Ateneo. At 8:00 A.M., Father Rosell arrived to relieve Father Viza. They joined at breakfast. Lt. Luis Taviel de Andrade came and Rizal thanked him for his gallant services. At 9:00 A.M., Fathers Jose Vilaclara (teacher in Ateneo) and Vicente Balaguer (Jesuit priest in Dapitan) visited the hero. After them came the Spanish journalist, Santiago Mataix, interviewed Rizal for his newspaper El Heraldo de Madrid. From 12:00 A.M. (noon) to 3:30 P.M., Rizal was left alone in his cell. He took his lunch, after which he was busy writing. It was probably during this time when he finished his farewell poem and hid it inside his alcoholcooking stove. (Not lamp as some biographers erroneously assert) which was given to him by Paz Pardo de Tavera. At the same he wrote his last letter to B lumentrit. At 3:30 P.M., Father Balaguer returned to Fort Santiago and discussed with his about his retraction of the anticatholic ideas in his writings and membership in Masonry. At 4:00 P.M., Rizals mother arrived. He asked forgiveness, they were both crying when the guards separated them. Shortly afterwards Trinidad entered the cell to fetch her mother. As they were leaving Rizal whispered that there is something inside the alcohol cooking stove Trinidad understood. This something was Rizals farewell poem. After the departure of Dona Teodora and Trinidad, Fathers Vilaclara and Estanislao march entered the cell, followed by Father Rosell. At 6:00 P.M. Rizal received a new visitor, Don Silvino Lopez Tunon. At 8:00 P.M., Rizal had his last supper. He informed Captain Dominguez that he forgave his enemies, including the military judges who condemned him to death. At 9:30 P.M., Don Gaspar Centano, the fiscal of the Royal Audiencia of Manila, visited Rizal. As a gracious host, Rizal offered him the best chair in the cell. After a

pleasant conversation, the fiscal left with a good impression of Rizals intelligence and noble character. At 10:00 P.M., Father Belaguer to Rizal submitted the draft of the retraction sent by the anti-Filipino Archbishop Bernardino Nozaleda for signature, but he rejected it because it was too long and he did not like it. A shorter one was presented later which was prepared by Father Pio Pi, which was acceptable to Rizal. Rizal then wrote his retraction, in which he abjured Masonry and his religious ideas, which were anti-catholic. At 3:00 o clock in the morning of December 30, 1896, Rizal heard mass, confessed his sins, and took the Holy Communion. At 5:30 A.M., he took his last breakfast. After this, he wrote two letters, for his family and other one for his brother Paciano. It was also then, when his wife Josephine Bracken arrived accompanied by Josefa. (Sister of Rizal). With tears in her eyes, she bade farewell. Rizal embraced her for the last time and gave her his last gift a religious book, Imitation of Christ, which he autographed: To My Dar Unhappy Wife, Josephine. 6:00 A.M., He wrote another letter to his beloved parents, asking for forgiveness for the sorrows that he had given them, and thanking them for their sacrifices to give him a good education. At 6:30 A.M., Rizal was prepared for the execution. A trumpet sounded announcing his forthcoming execution. With four soldiers as advance guards, Rizal a few meters behind walk calmly towards his slaughter place, accompanied by Lt. Luis Taviel de Andrade, two Jesuits Priests, and followed by more soldiers behind him. He was dressed in black suit, with a black derby hat, black shoes but with white shirts and black tie. Like any execution by muskertry, muffled sound of drums rent the air, with the group marching solemnly and slowly. Near the field a large group of spectators was out probably to see how a hero dies or to make it sure that Rizal will die. As they were walking to the field, Rizal looked at the sky and made a remark to one of the priests: How beautiful it is today, Father. What morning could be more serene! How clear are Corregidor and the mountains of Cavite! On morning like this, I used to take a walk with my sweetheart. While passing through in front of Ateneo, he asked one of the fathers, if the college towers were that of Ateneos, which was affirmed by one of the priests. In the Bagumbayan Field, the group stopped and he walked slowly to where he was told to stand-on a grassy lawn between two lampposts, overseeing the shores of the beautiful Manila Bay. He took time to bid farewell to his companions, and firmly shook their hands. One of the priests blessed him and offered a crucifix for him to kiss, which he did.

He then requested the commander of the firing squad to shoot him facing the firing squad, which was refused, with the commander telling him of the orders that he had to follow. He did as ordered reluctantly and turned his back and faced the sea, even as a Spanish Military doctor, Dr. Felipe Luis Castillo asked his permission to feel his pulse. Nothing could be more extraordinary that for a man facing the firing squad who will take off his life, as having a normal pulse. Rizal, who was intelligent, famous, respected, and who almost had everything during his time had no fear to die; it was a rare opportunity and he would want it in no other way. When the command Fuego! was heard, he made a supreme effort to face the firing squad, and his bulletriddled body instead turned to the right with his face facing the morning sun. it was exactly 7:03 A.M., th December 30 , 1896, when Jose Rizal died, his death was the life of the Filipinos. When he died Nationalism was born, at the prime of his life, thirty-five year of age, five months and eleven days. His Mission was accomplished!

Chapter XI: The After-Life in Memory An hour or so after the shooting a dead-wagon from San Juan de Dios Hospital took Rizal's body to Paco Cemetery. The civil governor of Manila was in charge and there also were present the members of a Church society whose duty it was to attend executions. Rizal had been wearing a black suit which he had obtained for his European trip, and a derby hat, not only appropriate for a funeral occasion because of their somber color, but also more desirable than white both for the full day's wear, since they had to be put on before the twenty-four hours in the chapel, and for the lying on the ground which would follow the execution of the sentence. A plain box inclosed the remains thus dressed, for even the hat was picked up and encoffined. No visitors were admitted to the cemetery while the interment was going on, and for several weeks after guards watched over the grave, lest Filipinos might come by night to steal away the body and apportion the clothing among themselves as relics of a martyr. Even the exact spot of the interment was intended to be unknown, but friends of the family were among the attendants at the burial and dropped into the grave a marble slab which had been furnished them, bearing the initials of the full baptismal name, Jose Protasio Rizal, in reversed order. The entry of the burial, like that of three of his followers of the Liga Filipina who were among the dozen executed a fortnight later, was on the back flyleaf of the cemetery register, with three or four words of explanation later erased and now unknown. On the previous page was the entry of a suicide's death, and following it is that of the British Consul who died on the eve of Manila's surrender and whose body, by the Archbishop's permission, was stored in a Paco niche till it could be removed to the Protestant (foreigners') cemetery at San Pedro Macati.

After Rizal's death Bracken promptly joined the revolutionary forces in Cavite province where she helped from taking care of the sick and wounded in the battlefield and boosting their morale , to helping operate reloading jigs for Mauser cartridges at the Imus arsenal under revolutionary General Pantalen Garca.

needed] [citation [1]

Imus was under threat of recapture so Bracken,

making her way through thicket and mud, moved with the operation to Maragondon, the Cavite mountain redoubt. She witnessed the Tejeros Conventionon March 22, 1897 prior to returning to Manila. She was later summoned by the Spanish Governor-General, who threatened her with torture and imprisonment if she did not leave the Islands. Owing however to her adoptive father's American citizenship, she could not be forcibly deported, but Bracken voluntarily returned to Hong Kong upon the advice of the American consul in Manila. [edit]Later life Upon returning to Hong Kong, she returned to her father's house. After his death, she married Vicente Abd, a Cebuanomestizo, who represented his father's tabacalera company in Hong Kong. A daughter, Dolores, was born to the couple on April 17, 1900. Bracken died of tuberculosis on March 15, 1902, in Hong Kong and was interred at the Happy Valley Cemetery in that country.

[1] [14]

Burial record of Rizal in the Paco register. (Facsimile.) The day of Rizal's execution, the day of his birth and the day of his first leaving his native land was a Wednesday. All that night, and the next day, the celebration continued the volunteers, who were particularly responsible, like their fellows in Cuba, for the atrocities which disgraced Spain's rule in the Philippines, being especially in evidence. It was their clamor that had made the bringing back of Rizal possible, their demands for his death had been most prominent in his so-called trial, and now they were praising themselves for their

"patriotism." The landlords had objected to having their land titles questioned and their taxes raised. The other friar orders, as well as these, were opposed to a campaign which sought their transfer from profitable parishes to self-sacrificing missionary labors. But probably none of them as organizations desired Rizal's death. Rizal's old teachers wished for the restoration of their former pupil to the faith of his childhood, from which they believed he had departed. Through Despujol they seem to have worked for an opportunity for influencing him, yet his death was certainly not in their plans. Some Filipinos, to save themselves, tried to complicate Rizal with the Katipunan uprising by palpable falsehoods. But not every man is heroic and these can hardly be blamed, for if all the alleged confessions were not secured by actual torture, they were made through fear of it, since in 1896 there was in Manila the legal practice of causing bodily suffering by mediaval methods supplemented by torments devised by modern science. Among the Spaniards in Manila then, reenforced by those whom the uprising had frightened out of the provinces, were a few who realized that they belonged among the classes caricatured in Rizal's novels-some incompetent, others dishonest, cruel ones, the illiterate, wretched specimens that had married outside their race to get money and find wives who would not know them for what they were, or drunken husbands of viragoes. They came to the Philippines because they were below the standard of their homeland. These talked the loudest and thus dominated the undisciplined volunteers. With nothing divine about them, since they had not forgotten, they did not forgive. So when the Tondo "discoverer" of the Katipunan fancied he saw opportunity for promotion in fanning their flame of wrath, they claimed their victims, and neither the panic-stricken populace nor the weakkneed government could withstand them. Once more it must be repeated that Spain has no monopoly of bad characters, nor suffers in the comparison of her honorable citizenship with that of other nationalities, but her system in the Philippines permitted abuses which good governments seek to avoid or, in the rare occasions when this is impossible, aim to punish. Here was the Spanish shortcoming, for these were the defects which made possible so strange a story as this biography unfolds. "Jose Rizal," said a recent Spanish writer, "was the living indictment of Spain's wretched colonial system."

Rizal's family were scattered among the homes of friends brave enough to risk the popular resentment against everyone in any way identified with the victim of their prejudice. As New Year's eve approached, the bands ceased playing and the marchers stopped parading. Their enthusiasm had worn itself out in the two continuous days of celebration, and there was a lessening of the hospitality with which these "heroes" who had "saved the fatherland" at first had been entertained. Their great day of the year became of more interest than further remembrance of the bloody occurrence on Bagumbayan Field. To those who mourned a son and a brother the change must have come as a welcome relief, for even sorrow has its degrees, and the exultation over the death embittered their grief.

The alcohol lamp in which the farewell poem was hidden. To the remote and humble home where Rizal's widow and the sister to whom he had promised a parting gift were sheltered, the Dapitan schoolboy who had attended his imprisoned teacher brought an alcohol cooking-lamp. It was midnight before they dared seek the "something" which Rizal had said was inside. The alcohol was emptied from the tank and, with a convenient hairpin, a tightly folded and doubled piece of paper was dislodged from where it had been wedged in, out of sight, so that its rattling might not betray it.

Facsimile of the opening lines of Rizal's last verses. It was a single sheet of notepaper bearing verses in Rizal's well-known handwriting and familiar style. Hastily the young boy copied them, making some minor mistakes owing to his agitation and unfamiliarity with the language, and the copy, without explanation, was mailed to Mr. Basa in Hongkong. Then the original was taken by the two women with their few possessions and they fled to join the insurgents in Cavite. The following translation of these verses was made by Charles Derbyshire: My Last Farewell

Grave of Rizal in Paco cemetery, Manila. The remains are now preserved in an urn.

Farewell, dear Fatherland, clime of the sun caress'd, Pearl of the Orient seas, our Eden lost! Gladly now I go to give thee this faded life's best,

And were it brighter, fresher, or more blest, Still would I give it thee, nor count the cost.

That my ashes may carpet thy earthly floor, Before into nothingness at last they are blown.

On the field of battle, 'mid the frenzy of fight, Others have given their lives, without doubt or heed; The place matters not-cypress or laurel or lily white, Scaffold of open plain, combat or martyrdom's plight, 'Tis ever the same, to serve our home and country's need.

Then will oblivion bring to me no care, As over thy vales and plains I sweep; Throbbing and cleansed in thy space and air, With color and light, with song and lament I fare, Ever repeating the faith that I keep.

I die just when I see the dawn break, Through the gloom of night, to herald the day; And if color is lacking my blood thou shalt take, Pour'd out at need for thy dear sake, To dye with its crimson the waking ray.

My Fatherland ador'd, that sadness to my sorrow lends, Beloved Filipinas, hear now my last good-by! I give thee all: parents and kindred and friends; For I go where no slave before the oppressor bends, Where faith can never kill, and God reigns e'er on high!

My dreams, when life first opened to me, My dreams, when the hopes of youth beat high, Were to see thy lov'd face, O gem of the Orient sea, From gloom and grief, from care and sorrow free; No blush on thy brow, no tear in thine eye

Farewell to you all, from my soul torn away, Friends of my childhood in the home dispossessed! Give thanks that I rest from the wearisome day! Farewell to thee, too, sweet friend that lightened my

Dream of my life, my living and burning desire, All hail! cries the soul that is now to take flight; All hail! And sweet it is for thee to expire; To die for thy sake, that thou mayst aspire; And sleep in thy bosom eternity's long night. way; Beloved creatures all, farewell! In death there is rest!

If over my grave some day thou seest grow, In the grassy sod, a humble flower, Draw it to thy lips and kiss my soul so, While I may feel on my brow in the cold tomb below The touch of thy tenderness, thy breath's warm power.

Rizal's farewell to his mother just before setting out to his execution. Let the moon beam over me soft and serene, Let the dawn shed over me its radiant flashes, Let the wind with sad lament over me keen; And if on my cross a bird should be seen, Let it trill there its hymn of peace to my ashes. For some time such belongings of Rizal as had been intrusted to Josefina had been in the care of the American Consul in Manila for as the adopted daughter of the American Taufer she had claimed his protection. Stories are told of her as a second Joan of Arc, but it is not likely that one of the few rifles which the insurgents had would be turned over to a woman. After a short experience in the field, much of it spent in nursing her sister-in-law through a fever, Mrs. Rizal returned to Manila. Then came a brief interview with the GovernorGeneral. He had learned that his "administrative powers" to exile without trial did not extend to foreigners, but by advice of her consul she soon sailed for Hongkong. Mrs. Rizal at first lived in the Basa home and received considerable attention from the Filipino colony. There was too great a difference between the freedom accorded Englishwomen and the restraints surrounding Spanish ladies however, to avoid difficulties and misunderstandings, for very long. She returned to her adopted father's house and after his death married Vicente Abad, a Cebuan, son of a Spaniard who had been prominent in the Tabacalera Company and had become an agent of theirs in Hongkong after he had completed his studies there. Two weeks after Rizal's execution a dozen other members of his "Liga Filipina" were executed on the Luneta. One was a millionaire, Francisco Roxas, who had lost his mind, and believing that he was in church, calmly spread his handkerchief on the ground and knelt upon it as had been his custom in childhood. An old

Let the sun draw the vapors up to the sky, And heavenward in purity bear my tardy protest; Let some kind soul o'er my untimely fate sigh, And in the still evening a prayer be lifted on high From thee, O my country, that in God I may rest.

Pray for all those that hapless have died, For all who have suffered the unmeasur'd pain; For our mothers that bitterly their woes have cried, For widows and orphans, for captives by torture tried; And then for thyself that redemption thou mayst gain.

And when the dark night wraps the graveyard around, With only the dead in their vigil to see; Break not my repose or the mystery profound, And perchance thou mayst hear a sad hymn resound; 'Tis I, O my country, raising a song unto thee.

When even my grave is remembered no more, Unmark'd by never a cross nor a stone; Let the plow sweep through it, the spade turn it o'er,

man, Moises Salvador, had been crippled by torture so that he could not stand and had to be laid upon the grass to be shot. The others met their death standing. That bravery and cruelty do not usually go together was amply demonstrated in Polavieja's case and by the volunteers. The latter once showed their patriotism, after a banquet, by going to the water's edge on the Luneta and firing volleys at the insurgents across the bay, miles away. The General was relieved of his command after he had fortified a camp with siege guns against the boloarmed insurgents, who, however, by captures from the Spaniards were gradually becoming better equipped. But he did not escape condemnation from his own countrymen, and when he visited Giron, years after he had returned to the Peninsula, circulars were distributed among the crowd, bearing Rizal's last verses, his portrait, and the charge that to Polavieja was due the loss of the Philippines to Spain. Float in a Rizal day parade. On the first anniversary of Rizal's execution some Spaniards desecrated the grave, while on one of the niches, rented for the purpose, many feet away, the family hung wreaths with Tagalog dedications but no name.

W. J. Bryan as an Rizal day orator. August 13, 1898, the Spanish flag came down from Fort Santiago in evidence of the surrender of the city. At the first opportunity Paco Cemetery was visited and Rizal's body raised for a more decent interment. Vainly his shoes were searched for a last message which he had said might be concealed there, for the dampness had made any paper unrecognizable. Then a simple cross was erected, resting on a marble block carved, as had been the smaller one which secretly had first marked the spot, with the reversed initials "R. P. J."

Monument at the corner of Rizal avenue, Manila. The Katipunan insurgents in time were bought off by General Primo de Rivera, once more returned to the Islands for further plunder. The money question does not concern Rizal's life, but his prediction of suffering to the country came true, for while the leaders with the first payment and hostages for their own safety sailed away to live securely in Hongkong, the poorer people who remained suffered the vengeance of a government which seems never to have kept a promise to its people. Whether reforms were pledged is disputed, but if any were, they never were put into effect. No more money was paid, and the first instalment, preserved by the prudent leaders, equipped them when, owing to Dewey's victory, they were enabled to return to their country.

Governor-General Forbes and his aide, delegate Mariano Ponce, at the unveiling of the tablet on the Rizal house.

The first issue of a Filipino newspaper under the new government was entirely dedicated to Rizal. The second anniversary of his execution was observed with general unanimity, his countrymen demonstrating that those who were seeing the dawn of the new day were not forgetful of the greatest of those who had fallen in the night, to paraphrase his own words. His widow returned and did live by giving lessons in English, at first privately in Cebu, where one of her pupils was the present and first Speaker of the Philippine Assembly, and afterwards as a government employee in the public schools and in the "Liceo" of Manila.

The last portrait of Jose Rizal's mother. With the establishment of civil government a new province was formed near Manila, including the land across the lake to which, as a lad in Kalamba, Rizal had often wonderingly looked, and the name of Rizal Province was given it. Later when public holidays were provided for by the new laws, the anniversary of Rizal's execution was in the list, and it has become the great day of the year, with the entire community uniting, for Spaniards no longer consider him to have been a traitor to Spain and the American authorities have founded a government in conformity with his teachings. On one of these occasions, December 30, 1905, William Jennings Bryan, "The Great American Commoner," gave the Rizal Day address, in the course of which he said: "If you will permit me to draw one lesson from the life of Rizal, I will say that he presents an example of a great man consecrated to his country's welfare. He, though dead, is a living rebuke to the scholar who selfishly enjoys the privilege of an ample education and does not impart the benefits of it to his fellows. His example is worth much to the people of these Islands, to the child who reads of him, to the young and old." Accepted model for the Rizal monument by the designer of the Swiss National Tell monument. The fiftieth anniversary of Rizal's birth was observed throughout the Archipelago with exercises in every community by public schools now organized along the lines he wished, to make self-dependent, capable men and women, strong in body as in mind, knowing and claiming their own rights, and recognizing and respecting those of others. His father died early in the year that the flags changed, but the mother lived to see honor done her son and to prove herself as worthy, for when the Philippine Legislature wanted to set aside a considerable sum for her use, she declined it with the true and rightfully proud assertion, that her family had never been patriotic for money. Her funeral, in 1911, was an occasion of public mourning, the Governor-General, Legislature and chief men of the Islands attending, and all public business being suspended by proclamation for the day. A capitol for the representatives of the free people of the Philippines, and worthy of the pioneer democratic government in the Orient, is soon to be erected on the Luneta, facing the big Rizal monument which will mark the place of execution of the man who gave his life to prepare his countrymen for the changed conditions.

The Rizal monument in front of the new Capitol.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Death of Jose RizalДокумент3 страницыThe Death of Jose RizalFray Relly OarОценок пока нет

- Rizal's Trial and Execution in BagumbayanДокумент12 страницRizal's Trial and Execution in BagumbayanJamella Madora75% (4)

- Rizal Arrested and Jailed in Fort SantiagoДокумент49 страницRizal Arrested and Jailed in Fort SantiagoMina Bianca Autencio83% (6)

- Exile Trial and Death Regine OragДокумент20 страницExile Trial and Death Regine OragAmare Et Servire0% (1)

- Trial and Execution of RizalДокумент3 страницыTrial and Execution of RizalJuan Emmanuel Ventura67% (9)

- Trial and Death of Jose RizalДокумент24 страницыTrial and Death of Jose RizalPatricia Denise Orquia50% (8)

- The Last Homecoming and Trial of RizalДокумент24 страницыThe Last Homecoming and Trial of Rizaljohnmarkrodriguez83% (12)

- Death - Jose RizalДокумент12 страницDeath - Jose RizalHilary Tangog100% (1)

- Brindis by Rizal and MoreДокумент13 страницBrindis by Rizal and MoreMaeca Sisican100% (1)

- Exile in DapitanДокумент63 страницыExile in DapitanCHABELITA DAVID100% (1)

- Rizal's Life - Exile, Trial, and DeathДокумент28 страницRizal's Life - Exile, Trial, and DeathGrace Antonette Garcia Dargantes100% (1)

- Rizal - Education - UstДокумент45 страницRizal - Education - UstJamil Berja IbardolazaОценок пока нет

- Synopsis of Noli Me TangereДокумент8 страницSynopsis of Noli Me TangereLouie Alejandro100% (3)

- Rizals Darkest Winter REPORT 1Документ7 страницRizals Darkest Winter REPORT 1Cristy Marie Macapanas100% (1)

- Rizals ExecutionДокумент22 страницыRizals ExecutionJanaela100% (2)

- RIZAL Chapter 5Документ24 страницыRIZAL Chapter 5Jomarie Asilo100% (2)

- Chapter 15 - 16Документ6 страницChapter 15 - 16Danica Franco100% (3)

- Rizal PreFinalДокумент3 страницыRizal PreFinalAngelica Catalla100% (1)

- Rizal in USTДокумент14 страницRizal in USTCharina Famero50% (2)

- Summary of Rizal's Life in DapitanДокумент3 страницыSummary of Rizal's Life in DapitanScarlette Joy Coopera78% (9)

- Rizal's Life Report by Group BДокумент31 страницаRizal's Life Report by Group Bazor ahai100% (1)

- Jose Rizal'S Higher EducationДокумент15 страницJose Rizal'S Higher EducationSherilyn Villaverde Delmo100% (2)

- Rizal Summary Chapter 23 To 25Документ7 страницRizal Summary Chapter 23 To 25Regidor Petiluna0% (1)

- Rizal's EducationДокумент16 страницRizal's EducationAnne Cervantes0% (1)

- RIZALДокумент15 страницRIZALCrystalОценок пока нет

- Jose Rizal - S Education AbroadДокумент2 страницыJose Rizal - S Education AbroadHarvey Matbagan64% (11)

- Jose Rizal To Paris and BerlinДокумент32 страницыJose Rizal To Paris and BerlinMJ Dalisay Caringal100% (1)

- Jose Rizal Exile in DapitanДокумент5 страницJose Rizal Exile in Dapitanleijulia100% (3)

- Rizal's Life Exile TrialДокумент46 страницRizal's Life Exile TrialMarixanne Niña Roldan Manzano100% (1)

- Jose Rizal at The University of Santo Tomas (1877-1882)Документ20 страницJose Rizal at The University of Santo Tomas (1877-1882)Caroline Untalan AclanОценок пока нет

- Noli Me Tangere (Finish)Документ23 страницыNoli Me Tangere (Finish)Jalan EstebanОценок пока нет

- Chapter 17, RizalДокумент6 страницChapter 17, RizalCarl Johnave Manigbas Monzon50% (2)

- Rizal Exile in Dapitan 1892 1896Документ21 страницаRizal Exile in Dapitan 1892 1896Jade España De Jesus100% (1)

- UNIT III Rizal Part 1Документ35 страницUNIT III Rizal Part 1danilo pastorfideОценок пока нет

- Compare and ContrastДокумент7 страницCompare and ContrastAngelica Pagaduan100% (1)

- First Homecoming - Jose RizalДокумент22 страницыFirst Homecoming - Jose RizalEdrianne Kimberly Bon100% (5)

- 3 La SolidaridadДокумент18 страниц3 La Solidaridadjunjurunjun100% (1)

- Rizal in Berlin Chapter 7Документ6 страницRizal in Berlin Chapter 7rain_dhell80% (15)

- Rizal's Journey InfographicДокумент1 страницаRizal's Journey InfographicKrystal shane75% (4)

- Rizal in Peninsular SpainДокумент20 страницRizal in Peninsular SpainJoshua Freddison Viray0% (2)

- Chapter 8 El FiliДокумент34 страницыChapter 8 El FiliFj EsguerraОценок пока нет

- Rizal Noli Me TangereДокумент35 страницRizal Noli Me TangereKristine Cantilero100% (2)

- Chapter 13 Rizal's Visit in United StatesДокумент13 страницChapter 13 Rizal's Visit in United StatesTricia Ann Destura100% (2)

- RizalДокумент2 страницыRizalAngelie Inducil100% (1)

- Rizal's Family TreeДокумент5 страницRizal's Family TreeKyle Campos0% (1)

- Rizal - Chapter 22Документ1 страницаRizal - Chapter 22Vanryanical100% (2)

- Chapter 16 in Belgian BrusselsДокумент8 страницChapter 16 in Belgian BrusselsariahriОценок пока нет

- RC - 1st Home Coming and 2nd LeavingДокумент7 страницRC - 1st Home Coming and 2nd LeavingMervyn TanОценок пока нет

- Cast of Characters in Rizal The MovieДокумент4 страницыCast of Characters in Rizal The MovieKobe Conrad Abellera67% (3)

- The Injustice Done My MotherДокумент2 страницыThe Injustice Done My MotherDiscoverup100% (6)

- Unit-5 Homecoming and Return To EuropeДокумент11 страницUnit-5 Homecoming and Return To EuropeAlmine50% (4)

- Exile, Trial, Death FinalДокумент25 страницExile, Trial, Death FinalSherilyn Villaverde DelmoОценок пока нет

- Noli Me TangereДокумент3 страницыNoli Me TangereFilipina MendadorОценок пока нет

- Jose Rizal in LondonДокумент4 страницыJose Rizal in LondonShawn Michael Doluntap60% (5)

- Rizal Chapter 3 SummaryДокумент1 страницаRizal Chapter 3 SummaryKevin Arellano BalaticoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 10 - RizalДокумент23 страницыChapter 10 - RizalMark Angelo S. Enriquez86% (36)

- What Are The Reasons Why Rizal Decided To Go To SpainДокумент2 страницыWhat Are The Reasons Why Rizal Decided To Go To SpainAaron LaroyaОценок пока нет

- Martyrdom at Bagumbayan Prepared By: Flor A. DocusinДокумент21 страницаMartyrdom at Bagumbayan Prepared By: Flor A. DocusinGuidance & Counseling Center - CSU AndrewsОценок пока нет

- Rizal ReportДокумент4 страницыRizal ReportMylene Sunga AbergasОценок пока нет

- Rizal ReviewerДокумент13 страницRizal ReviewerRosita MaritaОценок пока нет

- Abusing DrugsДокумент1 страницаAbusing DrugsgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Psychiatric Nursing Bullets (Nle & Nclex)Документ21 страницаPsychiatric Nursing Bullets (Nle & Nclex)Richard Ines Valino100% (24)

- Ca2 Mood Disorder Q&AДокумент7 страницCa2 Mood Disorder Q&AgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Map of AsiaДокумент1 страницаMap of AsiageejeiОценок пока нет

- Normal ValuesДокумент2 страницыNormal Valuesgeejei100% (1)

- Philippine Nursing LawsДокумент2 страницыPhilippine Nursing Lawszelai0% (1)

- Filipino ScientistsДокумент5 страницFilipino ScientistsgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Normal ValuesДокумент2 страницыNormal Valuesgeejei100% (1)

- NCP PEДокумент2 страницыNCP PEgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Intro COPDДокумент2 страницыIntro COPDGemery Jade ArtatesОценок пока нет

- Complex Regional Pain SyndromeДокумент10 страницComplex Regional Pain SyndromegeejeiОценок пока нет

- Human Growth and Development TheoriesДокумент5 страницHuman Growth and Development TheoriesgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Concept MapДокумент4 страницыConcept MapgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Thyroid Cancer Pathophysio WinjДокумент4 страницыThyroid Cancer Pathophysio WinjgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Structures of The HeartДокумент6 страницStructures of The HeartgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Amniotic Fluid ColorsДокумент2 страницыAmniotic Fluid ColorsgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Disaster Managemen T ServiceДокумент12 страницDisaster Managemen T ServicegeejeiОценок пока нет

- Drug Tab YheДокумент6 страницDrug Tab YhegeejeiОценок пока нет

- MedimapДокумент1 страницаMedimapgeejeiОценок пока нет

- THE Digesti VE SystemДокумент35 страницTHE Digesti VE SystemgeejeiОценок пока нет

- Detailed Lesson Plan English VДокумент5 страницDetailed Lesson Plan English VAljon Andol Ortega100% (1)

- Semi - Detailed Lesson Plan in Music 6 - For C.OДокумент4 страницыSemi - Detailed Lesson Plan in Music 6 - For C.OZai92% (13)

- Letter PahibaloДокумент4 страницыLetter PahibaloQueendelyn Eslawan BalabaОценок пока нет

- S3B The Brain Parts and FunctionДокумент1 страницаS3B The Brain Parts and FunctionNSABIMANA JANVIERОценок пока нет

- 1GДокумент2 страницы1GPaula Mae DacanayОценок пока нет

- Prediction As A Reading StrategyДокумент93 страницыPrediction As A Reading StrategySouhil BenaskeurОценок пока нет

- Amit M Agarwal Integral Calculus IIT JEE Main Advanced Fully Revised Edition For IITJEE Arihant Meerut PDFДокумент313 страницAmit M Agarwal Integral Calculus IIT JEE Main Advanced Fully Revised Edition For IITJEE Arihant Meerut PDFNikhilsai KasireddyОценок пока нет

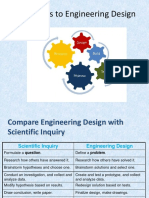

- Shift Gears To Engineering DesignДокумент14 страницShift Gears To Engineering DesignHamdan RamdanyОценок пока нет

- CommunityДокумент15 страницCommunityMerymie CastroОценок пока нет

- What Key Competencies Are Needed in The Digital Age?Документ60 страницWhat Key Competencies Are Needed in The Digital Age?marnekibОценок пока нет

- Palladio Virtuel Exhibition - ArchDailyДокумент5 страницPalladio Virtuel Exhibition - ArchDailyrajyamgarОценок пока нет

- ISO 13485 Why and HowДокумент29 страницISO 13485 Why and HowMarlin PohlmanОценок пока нет

- T.S. Eliot BiographyДокумент2 страницыT.S. Eliot BiographyWeber LiuОценок пока нет

- Business Plan Presentation RubricДокумент1 страницаBusiness Plan Presentation RubricLeopold Laset100% (4)

- Dongguk University Fellowship ProgramДокумент3 страницыDongguk University Fellowship ProgramCha CasasОценок пока нет

- Mini Research Project: Group E Mentor: Dr. Niraj ShresthaДокумент19 страницMini Research Project: Group E Mentor: Dr. Niraj ShresthaRavi BansalОценок пока нет

- Art Books 2 ListДокумент68 страницArt Books 2 ListCarina Parry100% (2)

- 00 General Inspector ResourceДокумент395 страниц00 General Inspector Resourcebooboosdad50% (2)

- Hospital Visit ReportДокумент3 страницыHospital Visit ReportRania FarranОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Accentedness in Speech and Employability of Malay English Speaking Undergraduates at IIUMДокумент24 страницыAn Analysis of Accentedness in Speech and Employability of Malay English Speaking Undergraduates at IIUMKaty AndersonОценок пока нет

- Science Unit-Wheels and LeversДокумент11 страницScience Unit-Wheels and Leversapi-535552931Оценок пока нет

- Financial Literacy and Saving Behavior of Students in Hagonoy National High School.2Документ15 страницFinancial Literacy and Saving Behavior of Students in Hagonoy National High School.2Ma Aragil Valentine Jomoc100% (1)

- The Effect of Gamification Towards The Eleventh Grade Students EngagementДокумент22 страницыThe Effect of Gamification Towards The Eleventh Grade Students EngagementDian Utami DewiОценок пока нет

- Z Fuller 16343229 102091 Drama2b 1h 2016 Assessment 2Документ26 страницZ Fuller 16343229 102091 Drama2b 1h 2016 Assessment 2api-305377750Оценок пока нет

- Pertanyaan KecuranganДокумент8 страницPertanyaan KecuranganVitra Trie SetianaОценок пока нет

- Clinical Nursing Judgment 1Документ5 страницClinical Nursing Judgment 1api-601489653Оценок пока нет

- Use Your Shoe!: Suggested Grade Range: 6-8 Approximate Time: 2 Hours State of California Content StandardsДокумент12 страницUse Your Shoe!: Suggested Grade Range: 6-8 Approximate Time: 2 Hours State of California Content StandardsGlenda HernandezОценок пока нет

- ใบสมัครงาน อังกฤษДокумент5 страницใบสมัครงาน อังกฤษTasama PungpongОценок пока нет

- Science Olympiad FlyerДокумент2 страницыScience Olympiad FlyerIra RozenОценок пока нет

- Choral Pedagogy and Vocal HealthДокумент7 страницChoral Pedagogy and Vocal Healthradamir100% (1)