Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

3876352

Загружено:

최두영Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

3876352

Загружено:

최두영Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Utility Privatisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case Study of Water Author(s): Kate Bayliss Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal

of Modern African Studies, Vol. 41, No. 4 (Dec., 2003), pp. 507-531 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3876352 . Accessed: 30/12/2011 05:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern African Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

J. of ModernAfricanStudies,41, 4 (2003), PP- 507-531. ? 2003 Cambridge University Press DOI: Io.Io7/Soo22278Xo3oo4415 Printed in the United Kingdom

Utility priva tisa tion in Sub-Saharan Africa: a case study of water

Kate Bayliss*

ABSTRACT

Over the past twenty years, the focus of developmentpolicy has shiftedfrom the state to the privatesector. Privatisation now centralto utilityreformin much of is SSA. This paper sets out developments in water privatisationand reviews the evidence regardingits impact. Water privatisationhas been carriedout to some degree in at least fourteen countriesin the region, and many other governments are at various stages in the privatisationprocess. However, in some cases privatisation has been difficultto achieve, and a few countrieshave successfullyprovided water under public ownership. Evidence on the impact of privatisation indicates that the performanceof privatisedutilities has not changed dramatically, but that enterpriseshave continued to perform well, or not so well, depending both on their statewhen they were privatisedand on the widereconomic context. The evidence points to internal improvements in terms of financial management. However, governmentsface considerabledifficultiesin attracting investors and regulatingprivate utilities. Furthermore,privatisationfails to addresssome of the fundamentalconstraintsaffectingwater utilitiesin SSA, such as finance, the politicisednature of service delivery,and lack of access for the poor. A preoccupationwith ownershipmay obscure the wider goals of reform.

INTRODUCTION

The last two decades have witnessed a transformationin development

policy, as state-led practices have become increasingly discredited and growing emphasis has been placed on the private sector. As part of this trend, privatisation has become a cornerstone of reform programmes

which are adopting a 'market-oriented'policy agenda. Despite the repolicy throughout sub-SaharanAfrica (SSA). While many governments

have taken steps to implement privatisation programmes, progress has

* University of Greenwich, London.

alignment from structural adjustment to poverty reduction as the focus of the developmentframework the late 199Os,privatisation remainsa core in

508

KATE BAYLISS

been slower than was anticipated in the early I98os, and for a long period such programmes only featured smaller-scale enterprises. Now, due in part to donor pressure, governments are beginning to privatise larger enterprises and address the more contentious sales. In much of the region, the record of the public sector has been far from impressive and there has been much optimism about the benefits of private enterprise. However, the privatisation of such strategic industries has raised a number of concerns. Firstly, these enterprises are usually monopolistic and, in the absence of competition, require effective regulation if private ownership is to be beneficial for the wider economy. However, in much of the region state institutions are weak and this limits regulatory capacity. Secondly, the scale of operations in these sectors usually means that the participation of a foreign investor is essential. However, the region is widely perceived as risky by investors, and privatisation requires concerted efforts to attract investment, particularly as so many countries are adopting the same policies simultaneously. Finally, the control and operation of such enterprises is often politically charged. Privatisation does not remove the political nature of these activities, and may do little to ease the involvement of politicians in key sectoral decisions. This paper analyses developments in water privatisation in SSA, a region in which in 2000 only 57 % of the population had access to safe water (Unicef 2002). Hence there is an urgent need to improve service delivery. Water privatisation is increasingly widespread and is now on the agenda in most countries. The paper sketches the background, and then examines what privatisation has taken place in the region. This is followed by an analysis of the findings from case studies on the impact of water privatisation. The final sections consider the lessons learned and policy implications. The paper highlights some positive experiences with state ownership in the water sector, and shows that privatisation has had limited benefits, indicating that ownership is not the defining criterion for performance, and that focusing on privatisation as the centrepiece of water policy may obscure more significant constraints to sector reform.

BACKGROUND

Privatisation in SSA has lagged behind the rest of the world (Megginson & Netter 2001). Kayizzi-Mugerwa (2002) identifies four phases in African privatisation. The first was a stalemate with the slow privatisation of small enterprises, which was the situation in most countries until the late 1980s. The second phase he terms the 'path of least resistance', where governments embarked on rapid privatisation of small firms, but hesitated when

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

509

it came to larger enterprises. Eventually the stock of small firms ran out and the larger enterprises had to be dealt with, giving rise to stage three 'breaking resistance' - reflecting the position of most SSA countries in the first half of the I99os. At this stage, privatisation was accepted and the machinery for implementation was in place, but institutional and political obstacles prevented the privatisation of larger firms. The fourth and final phase was a 'fully fledged privatisation effort', where all utilities were up for sale. Few countries, he says, have reached this stage. This classification is borne out by the experience of many countries in the region. For example, privatisation in Nigeria was at first limited to small firms with low capital intensity (Ariyo & Jerome 1999). In Cameroon, progress was slowed by a mutually reinforcing pattern of lack of commitment with lack of capability (van de Walle 1994). In Tanzania, slow progress was attributed to asset valuation procedures as well as the bureaucratic process surrounding the whole privatisation process (Temu & Due 1998). In Mozambique, privatisation was initially slow and consisted of smaller enterprises, but escalated dramatically in terms of rate and scale in the 199os (Castel-Branco et al. 2001). Now many countries are privatising utilities, mainly under the guidance of international donors (Bayliss 2002). To some extent this is due to poor performance under public ownership (although not all public sectors have had bad results). In the water sector, for example, in many cases leakage levels have been high due to aging infrastructure and illegal connections. There are weak billing and revenue collection mechanisms, and in some cases public sector organisations fail to pay their water bills and the tariff structure has failed to recoup costs. In Tanzania, World Bank advisers suggest that only about 8 % of all water produced was being billed (Wateraid Privatisation is usually part of a wider reform process to improve 2002). performance. Other aspects of reform include tariff adjustment, ringfencing of finances, and the introduction of performance contracts where the enterprise is required to meet specific targets. Electricity and water industries have in many cases been 'unbundled', whereby the enterprise is divided into separate operational units. In the electricity sector, state utilities have been broken up according to their function in the supply chain, so that separate entities are responsible for the generation, distribution and transmission of electricity. In the water sector, state operations have been split between the ownership and the operation of the water supply network. The objective of such unbundling is to improve transparency and accountability. This approach has also served to isolate areas of operation that are relatively straightforward to privatise. In electricity, the private sector is predominantly involved in the generation of electricity which it

510

KATE BAYLISS

sells to the national grid. Some countries have begun privatisation of electricity distribution enterprises, but in most cases the transmission network is retained by the state (see Bayliss 2001). In water, the private sector usually assumes control of the operation of the water supply network, while the state retains ownership of the assets and responsibility for capital investment. The term privatisation encompasses a spectrum of contractual arrangements between the government and the private sector, ranging from a management contract through to divestiture (i.e. ownership transfer).' One factor that distinguishes the different arrangements is the degree to which risk is transferred to the private sector. For example, with a management contract the private firm assumes relatively little risk, operating the enterprise for a fixed remuneration. When it comes to leases and concessions, the government retains ownership of the assets and the private investor operates them. The distinction between a lease and concession is a hazy one and the terms are often used interchangeably, but usually the distinction rests on which party is responsible for investment in infrastructure. With a lease it is the government, while with a concession it is the private investor. However, the division of responsibility between government and investor over maintenance and investment has been a key source of disagreement in privatisation contracts (see below).

WHAT HAS BEEN PRIVATISED?

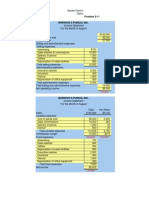

Table I lists the major water privatisation contracts in SSA to the end of 2002. Of the eighteen ongoing contracts, three are management contracts for two to five years, awarded in 2001/2, while the longer-term concession contracts run for up to 50 years. Twelve of the contracts have been awarded since I999, suggesting that the pace of privatisation is increasing. C6te d'Ivoire stands out as something of an anomaly, in that it privatised its water in 1960, nearly 30 years before the next privatisation which was in Guinea in 1989. Francophone countries have privatised more than the rest of SSA, possibly because of links with France, where most of the world's private water business originates. The contracts are dominated by three French MNCs - Saur, Suez and Vivendi - which also dominate private water sector activity in most of the world (Hall 2002). Africa is particularly important to Saur, where the company earned about one fifth of its revenue in 2001 (Weimer 2002). The company has four long-term contracts (CAR, C6te d'Ivoire, Senegal and South Africa), as well as Guinea (although this may be due to finish imminently). It is also involved in separate electricity projects in C6te d'Ivoire and Guinea. Vivendi has three big contracts, in Chad, Gabon and Niger,

WATER

PRIVATISATION TABLE I

IN AFRICA

511

Water privatisation contracts in sub-Saharan Africa, December

Date 2002 Country Congo (Brazzaville) Contract duration and type Short-term management contract prior to award of 25 year management contract 2 year management contract 5 year management contract io year renewable contract for water and electricity supply 5 year management contract 30 year concession (management contract initially) 20 year lease 50 year lease Maputo and Motola: 15 years 3 other cities: 5 years 30 year lease 30 year lease 20 year concession 1o year lease io year lease 25 year lease 15 year lease 1o year lease Contract started in 1960, renegotiated for 20 years in 1987

2002

Lead Company Biwater

2002 2001 2001 2001 2000 2000 1999 1999 1999 1999 1997 1996 1993 1992 1991 1989 1960

Uganda Burkina Faso Niger South Africa Chad Mali Cape Verde Mozambique South Africa (Nelspruit) South Africa (Dolphin Coast) Gabon Senegal South Africa (Stutterheim) South Africa (Queenstown) Central African Rep Guinea C6te d'Ivoire

Suez - Ondeo Vivendi Vivendi Suez Vivendi Saur Aguas de Portugal/EdP Aguas de Portugal Biwater/NUON Saur Vivendi Saur Suez Suez Saur Saur Saur

Source:PSIRU database www.psiru.org; Biwater press release, October 2002, for Congo-Brazzaville.

all acquired in the past five years. Suez has just one long-term contract, Queenstown in South Africa; its other contracts are short term (South Africa, 5 years; Uganda, 2 years), and they now have two construction contracts in the water sector (Burkina Faso, Senegal). Despite the French dominance, two other firms have managed to move into the region. In March 2002, the UK firm Biwater won a contract in Congo, and the Portuguese government's Aguas de Portugal (AdP) has contracts in Cape Verde and Mozambique. The table shows that in some cases, rather than unbundling the separate components of the electricity and water services, these have been sold as a single, combined enterprise. Four of the enterprises privatised are joint electricity and water utilities (Cape Verde, Chad, Gabon and Mali). This can provide economies of scale, but also ensures that the enterprise is

512

KATE BAYLISS

of sufficient size to be of interest to investors, as was the case, for example, with the sale of the water and electricity utility in Gabon (Samuel 1999). Guinea is the only contract which has run its course. The io-year contract expired in 1999, although it has been renewed on an annual basis. The contract did not run smoothly and prices have escalated. The government subsequently signed an interim one-year lease contract. However, efforts to negotiate a new 15-year lease contract broke down, and the government asked for World Bank assistance with an interim organisational arrangement and with organising a competitive tender for the water utility SEEG (Societei d'Exploitation d'Eaux Guinee). The World Bank (2001) appears to be unhappy with the breakdown in negotiations: 'After more than Io years of private management of water operations in Guinea, the outcome of these negotiations represents a serious drawback to one of the first established private public partnerships in the sector, and in the region. Delays in paying Government's water consumption is still one of the main issues in the sector.' For the government, however, the high prices charged under the concession were not acceptable. According to Guinea's national radio in January 2001, the existing lease arrangement was to be replaced by a new privatisation in the hope that such a measure might bring prices down. 'After more than io years of contract operations between the two firms, it was realised that the consumer was paying too high a price for pipe borne water' (PANA 30.1.2001). In a move reminiscentof re-nationalisation, SONEG, the public sector owner of the water infrastructure, was reportedly intending to assume water management in urban centres (ibid.). So far privatisation has been carried out to some degree in at least fourteen countries in SSA. A number of other governments are at various stages in the privatisation process. Some countries have been attempting to privatise for years but without success. Table 2 lists developments in countries which were in the process of privatising at the end of 2002. Some governments intended to privatise but have found the process interminably slow. Despite lengthy negotiations, privatisation processes have been running for years, sometimes with no conclusion in sight. These experiences demonstrate the difficulties that privatisation presents. In Tanzania, for example, privatisation of the poorly performing Dar es Salaam Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DAWASA) was one of the preconditions given for Tanzania to qualify for the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative of the World Bank and the IMF (PANA 6.8.2002). The government began the privatisation process in 1997, when international operators were invited to pre-qualify, but no contract was awarded and a subsequent bidding round for a lease contract took place in 1999. Two

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

513

TABLE

2 2002)

Planned privatisations (December

Burundi

Nigeria

Rwanda Uganda

Privatisation ministerreportedin February2002 that the privatisation of the National Water and Power Distributionand ProductionCompany (REGIDESO)was in an advancedstage.a World Bank is assistingwith establishinga regulatoryframeworkfor privatising the water sector througha concessioncontract;b February2002, the in governmentof Nigeria receiveda 14person delegationof potentialinvestorsin the water sector from the UK.c Managementcontractfor the electricityand water utility,Electrogaz,scheduled

to be completed in 2002.d

Zambia Kenya

Malawi Ghana

Tanzania Guinea-Bissau Sources:

Ugandan water authorityhas a managementcontractwith Suez subsidiary, Ondeo, with a view to eventuallyestablishinga lease arrangement separatingresponsibilitiesfor operatingthe water supplyfrom developing the infrastructure.e World Bank is assistingwith the privatisation the LusakaWater and of Sewerage Company.b World Bank is developingplans for privatisingwater supplyand sewerage in Mombassaand the coastal regionb well as providingtechnical as assistancefor the preparationof a privatisationstrategyfor the water supply and seweragein Nairobi.b World Bank is providingassistancefor an assessmentof the options for private involvementin the water sector in Blantyreand Lilongwe.b Bids invited for two leases for the nationalwater supplywhich has been divided into two 'businessunits'; one lease will run for 30 years and one for 10 years./Private operatorsare expected to be in place by March 2003. In 2002, bids were receivedfrom Biwater(UK) and Gauff (Germany)for the dollar-basedcontract.Suez and Vivendi both withdrew,despite pre-qualifying.a Revised privatisation plans reportedin 2002.g

a PANA 28.2.2002; b World Bank PPIAF; c News 12.2.2002; Afriica d AP Worldstream 15.12.2001; e Klahanie & Tanner 2001;

f ISODEC (IntegratedSocial Development Centre),Accra, Ghana 2002. 'Why we must stop water in privatisation Ghana.' www.isodec.org.gh;

g AfricaEnergy& Mining 27.2.2002.

companies (Saur and Vivendi) submitted bids, but their financial bids were found to be non-compliant. Bidding was then re-launched in 2001. This time there were too few bidders (Wateraid 2002). In 2002, two bids were

received, from Biwater (UK) and Gauff (Germany),and two companies

withdrew (Suez and Vivendi). A contract was finally awarded in 2003, six years after the initial pre-qualification process. In practice, privatisation has meant reaching a balance between expectations from privatisation and the commercial reality of international investors. Where this balance cannot be achieved, efforts to privatise have

514

KATE BAYLISS

failed. It is not always easy to attract investors and, where consumers have low incomes, water contracts will fail to meet the commercial viability criteria of MNCs. For example, in Cameroon, it was reported in May 2000 that the utility, SNEC, had been sold to Suez, which was the only company that submitted a bid. The government had had to privatise at speed to meet conditions set by donors for the receipt of aid (Reuters 16.5.2000). However, some two years later the negotiations stalled. It was reported that the price put forward was considered by the government to be too low.2 In 1999, the UK company Biwater, after extensive negotiation, withdrew from a water privatisation project in Zimbabwe on the grounds that local consumers could not afford tariffs that were sufficient to generate an adequate commercial return for the company. According to the then Biwater country manager for Zimbabwe, Richard Whiting, 'from a social point of view, these kinds of projects are viable but unfortunately from a 10.12.1999). Independent private sector point of view they are not' (Zimbabwe Once contracts are in place they are rarely terminated, but there are some cases. In The Gambia, a Io-year contract with a subsidiary of Generale des Eaux (now known as Vivendi) was terminated following a military coup. From the start, relations between the private operator and the government were tense. The situation deteriorated further after the 1994 coup, when the private operator initiated an aggressive campaign to disconnect non-payers (Kerf 2000). In 1995, the new government was reported to have arrested staff under allegations of contractual failures (Financial Times 22.3.1995). In July 2001, the government of Kenya suspended a controversial water contract with a Vivendi subsidiary. Critics were concerned that the company was to make a substantial profit3 from installing a new billing system, while investing nothing in infrastructure during the project's Io-year duration. Although, in response to protests, Vivendi agreed to contribute a further $150 million in expansion, repair and maintenance of the network, there was still further criticism of the project, this time from the World Bank on the grounds that it was expensive and had not been competitively tendered (East African20.8.2001). In South Africa, the contract for Fort Beaufort (Nkonkobe) water was nullified in December 2001, effectively cancelling the contract with Suez subsidiary, WSSA, six years after it was awarded. There had been ongoing difficulties with payment for the contract (Bayliss et al. 2002), which was terminated when it emerged that required procedures had not been adhered to. According to the lawyer for Nkonkobe council, the court found the contract was invalid as it had not been published first for comment by members of the public, and approval from the local government MEC was

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

515

online 15.I2.2001). Outside the extreme case of a never obtained (Dispatch military coup, as in The Gambia, the cases of Kenya and South Africa indicate that even where there are difficulties with the contract, termination hinges on procedural irregularities. Often the drive for privatisation stems in part from the disappointing performance of the public sector in the supply of water. However, this experience is not universal and in some parts of SSA water has been provided effectively by the public sector. (This is not to say, however, that these will not be privatised.) Botswana, Namibia and Burkina Faso all demonstrate that public provision of water does not necessarily result in inefficiency and over-staffing. In Botswana the Water Utilities Corporation (WUC) substantially increased the proportion of the population with access to safe water over the period from i970 to 1998.4 The WUC operates on commercial principles and sets tariffs which allow a 'fair' return on its services and assets employed. The corporation maintains a policy of cross-subsidy to ensure that domestic consumers at the lowest band have access to water supplies. The board members are appointed by the minister of mineral resources and water affairs.5 The Namibian Water Corporation Ltd (NamWater) started operating as a fully government owned company on I April 1998. By 2000, the company recorded an operating profit just two years after restructuring, when it had not been expected to break even for five years. This was achieved by increasing debt collection and cutting costs. Total employee numbers were reduced from 1,180 to 975. For the staff who remained, wages and benefits increased, working conditions improved and staff development programmes were introduced. NamWater receives a government subsidy which will be phased out over a period of five years. In 2000, the company redesigned the tariff structure on a zone basis to enable cross subsidy. All surpluses are accumulated into a fund which is used to finance capital development renewal expenditure and reduces the need for external borrowing (NamWater 2000). The water utility in Burkina Faso, ONEA, was restructured between 1990 and 1998. The process aimed to create a commercially viable enterprise, while expanding service to the poor and low-income areas, with a commitment to ensuring that low-income groups did not pay more for services than connected households. The water utility has since recorded impressive indicators. Coverage reached 85-6 %, Unaccounted-for-Water (UFW) was 18 %, collection was above 95 %, metering was 10o %, and cost recovery was at 96 % of all costs (Werchota 2001). While the public provision of water has been problematic in many countries, this is not always the case as the above examples demonstrate. Some public sector utilities

516

KATE BAYLISS

have performed well while others have not. This is not to say that public or private ownership is the solution, but that the quality of enterprise performance cannot be predetermined on the basis of ownership.

WHAT HAS BEEN THE IMPACT OF PRIVATISATION?

Although many countries are planning to privatise, there has been little research into the effects of water privatisation. This section reviews evidence on the impact of privatisation, and relies heavily on the few case studies that have been carried out in sub-Saharan Africa (outside South Africa). These have been in Guinea (Menard & Clarke 2ooob; Brook & Gabon (Tremolet Locussol 2001); C6te d'Ivoire (Menard & Clarke 2000oooa); & Neale 2002); Senegal and C6te d'Ivoire (Tremolet et al. 2002) and C6te d'Ivoire, Senegal, and Guinea (Kerf 2000). Data on water services are notoriously unreliable, and this section sets out to isolate general trends rather than specifics. The evidence from these case studies shows, broadly, that privatisation has not performed miracles but that enterprises continue to perform well, or not so well, depending on their state when they were privatised and the wider economic context. Furthermore, all countries had difficulties with regulation, and politics remained influential. The following sections assess the available evidence, with respect to pricing, performance, regulation, risk and political exposure. Pricing The reform of water pricing is not inherently linked to privatisation, although the two often form part of a wider reform process. While privatisation may be associated with marginal-cost pricing, there is no a priori reason why privatised water cannot be subsidised, or why a public sector water company cannot be self-financing. Tariff setting is usually the responsibility of government. The method of pricing depends on the objectives of the water agency and the government. In general, crosssubsidisation across user groups is common (Renzetti 2000). While privatisation is unlikely to affect the structure of the water tariff, it may have an impact on pricing levels. Privatisation may affect prices if it has an impact on costs. Privatisation may reduce costs if it results in greater productive efficiency. However, effective regulation is essential to ensure that the benefits of such gains reach consumers and not just shareholders. Furthermore, the need for investors to earn a commercial return may put upward pressure on prices. Privatisation may also affect prices if investors want assurance of revenue

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

517

stability without having to rely on government subsidies. Hence contracts may provide for Automatic Tariff Adjustment, where factors that affect costs (such as inflation and currency depreciation) may be passed on to consumers. For example, an Automatic Tariff Adjustment is planned for the Ghanaian water privatisation (Weissman 2002). However, the pricing issue is complex as increasing prices may reduce demand, and thus have an adverse impact on the overall revenue position. Prices may be increased before privatisation as part of the reform process in order to make the enterprises more attractive to investors. If prices subsequently fall it is difficult to be clear about the overall privatisation impact. In Gabon, for example, prices were increased in the build-up to privatisation. Vivendi then won the contract on the basis of a proposed 17-25% price reduction and prices have since fallen (Tremolet & Neale but it is not clear how much they were increased in the first place. In 2002) C6te d'Ivoire, the water contract was considerably revised when it was renegotiated in 1987. As part of the renegotiations, the private operator agreed to reduce its remuneration by 20 %, which was passed on to end consumers (Menard & Clarke 2000a), suggesting that pricing has more to do with the bargaining strengths of different parties than costs. In Guinea, prices rose to unaffordable levels as a result of water privatisation and this had a significant impact on other policy outcomes. Before privatisation prices were very low at $o.12 per cubic metre (pcm). They were expected to increase to $0.76 before falling to $o.68. However prices rose by more than expected, reaching $0o.83 pcm in 1996. As a result, there was a steep fall in collections and a rise in inactive connections. Prices were higher than average prices in Africa and Latin America, and it became difficult even for wealthy people to pay. It is not entirely clear why prices rose so much, but there appear to be a number of contributory causes related to privatisation. Costs were high because of low labour productivity, a large presence of expatriate staff and considerable bad debt. The pressure from the regulator to control these costs was weak - the government did not renegotiate a reduction of the lease contractor rate or revise the cost indexation formula (Brook & Locussol 2001). The huge price increase seemed to undermine the bidding process which was won on the strength of a low bid tariff. Perfomance This section assesses the impact of privatisation on key performance indicators before considering some of the underlying reasons for such outcomes in the following sections. The historical and economic context in

518

KATE

BAYLISS

which privatisation is implemented has a crucial impact on the outcome of the policy. In Guinea, the water sector was in crisis before privatisation in 1989. In many ways this mirrored the country's wider economic situation. The utility was under funded and over-staffed. Collection rates were very low, and in 1987 it was estimated that only 15% of those billed paid for the water. The network was in very poor shape, with unaccounted for water (UFW) at 50% and a connection rate below 40 % (Menard & Clarke 2000b). Before privatisation, the government established SONEG - the state-owned national water authority. The lease contract was awarded to Saur (with Vivendi) which established the management company, SEEG. In Gabon, on the other hand, the water utility was performing well before privatisation. According to Frangois Wohrer (Financial Times 26.3.1997), investment officer in IFC's privatisation and financial advisory group, SEEG (the utilities of both Gabon and Guinea have the acronym SEEG) was a 'relatively wealthy company', in better shape than many African utilities. Speaking just before the contract was awarded, Wohrer said: 'They have been showing limited losses but will make a fairly decent profit in 1996 ... The company was a little messy before 1993 but there has been a nice cleaning process over the last three years. There is no overstaffing and the company is quite well managed.' The utility in Senegal was also performing well before privatisation in 1996. Water services within urban centres were well managed by the public utility, SONEES. Labour productivity was high (7 per I,ooo connections in 1994), UFW was at 30 % in 1994, and 8o % of the population had access to water (Kerf However, the company's financial position was overshadowed by 2000). low prices and non-payment by government agencies. Aside from any efforts by the investors, following privatisation the financial position of the water sector was greatly improved thanks to a World Bank loan of $247m (Tremolet et al. 2002). In C te d'Ivoire the water utility SODECI was privatised in 1960. Operational performance has until recently been very good. Table 3 collates some key findings from the various case studies on performance indicators, comparing the position before and after privatisation where data are available. 'Before' figures are not provided for C te d'Ivoire, as water was privatised in 1960. The figures need qualifying, as it is difficult to estimate them with any accuracy. Indicators may also vary depending on the timing in relation to reform. However, the data provide an insight into the general trends of pre- and post-privatisation performance. Generally, the figures indicate that in Gabon and Senegal good performance has been marginally improved, while in Guinea poor performance has continued.

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

519

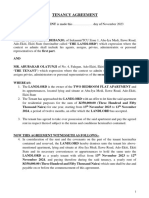

TABLE 3 Selected performance indicators: before and after privatisation

Unaccounted for water (UFW) % Before After Connections" % Before After Before Collection rates % After

Guinea Gabon Senegal

C6te d'Ivoire

50

47

14

22 16

38 49'3

47

62

75 'high'

91 -

31

8o

-

82

84

60 93 97

High from private sector,

low from public sector

a The connection rate measuresthe percentage of the total populationwith access to safe water. In

some cases, figuresreferjust to main cities. See below. Sources: Ctte d'Ivoire:Kerf 2000, Menard & Clarke2oooa, Tremolet et al. 2002; Gabon: Tremolet & Neale 2002; Guinea: Brook & Locussol 2001, Kerf 2000, Menard & Clarke 2000b; Senegal: Kerf 2000, Tremolet et al. 2002.

In Guinea, io years after the start of the lease, unaccounted for water (UFW) was still high at about 47 %. The structure of the contract meant that the private operator had little incentive to reduce UFW (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Gabon losses were reported to be on average about 14 % in 2002 (Tremolet & Neale 2002). It is not clear if this is a major improvement, but the enterprise was operating well before privatisation. In Senegal, leakage was cut from 31% to 22 %, although this was still higher than the 15% target set in the contract (Tremolet 2002). In C6te d'Ivoire, UFW has been consistently less than 20 % in Abidjan since the early i960s, and was about 16 % nationally (Menard & Clarke 2oooa). However, following recent social tensions in the country, the losses were reported to be increasing, in 2002 reaching about 23 % of water production (Tremolet 2002). Expansion of the network was limited in Guinea, increasing from about 38 % to 47 % (Brook Cowen 1999). To some extent, the increase in connections that did occur was financed by the World Bank under its Second Water Supply Project. The limited increase is due partly to the high price of water and connection costs. System expansion was also slowed by disagreements between SEEG and SONEG over who was responsible for what. The low connection rate means that water-related health problems remain a major issue due to the large number of customers who consume unsafe water (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Gabon, the private operator appears to have overshot targets for increasing the connection rate by a comfortable margin. In the capital, Libreville, the connection rate into creased from 49'3 ?% 62%. However, the company admits that this apsuccess does not mean that they invested particular energies into parent

520

KATE BAYLISS

extending services, but simply that the targets were based on initial coverage figures that were underestimated(Tremolet & Neale 2002). In Dakar, Senegal, about 80 % of the populationhad access to safe drinking water in 1994.This increasedslightlyto 82 % four years afterprivatisation (Kerf 2000). In Abidjan,C6te d'Ivoire,the connection rate declined from 81 % in 1980 to 74 % in 1986, but rose again to reach about 84 % in 1996 (Menard& Clarke2oooa). In Guinea,one of the firsteffectsofprivatisation a massiveincreasein was the extent of metering.Beforereformabout 5 %of customershad working meters. By 1996, 98 % of private customersand 0oo of administration % connections were metered. Bill collection from private customers improved initiallybut this fell when the price increased.The fall in collection rates is due to the increasein the price of water, as well as the fact that the governmentstill fails to pay its water bills (Menard& Clarke2ooob). In Gabon, customers were already paying their bills before privatisation, when levels of recoveryon monthlybilling for electricityand water were about 93 %. Accordingto the IFC advisoron the projectbefore the privatisation,'People are paying their bills quite well - this is a very high level of compliance for a developing country, and helps to explain the interestfrom bidders' (FT 26.3.1997).In Senegal, bill collection was also but good beforeprivatisation, improvedfrom 91 % to 97 %, due in part to the governmentstartingto pay its bills, as well as the adoption of a strict disconnection policy (Tremolet et al. 2002). In Cote d'Ivoire, collection rates were high from the private sector but low from the public sector. social cost in the form of However, this achievementconcealsa substantial disconnectionof non-payers(Tremolet& Neale 2002). While the performancedata indicate improvementswhen it comes to the proportionof the population with access to safe water, these figures are underminedby the existence of a high number of disconnectionsfor non-payment.In Senegal, in 2002, it was reportedthat as many as 12%of existingconnectionswere not in servicein the areaof operationin the capital, Dakar.The rate outsideDakarwas even higher (Tremoletet al. 2002). In C6te d'Ivoire, private sector customers have been routinely cut off for non-payment,even though the payment system was designed to discourage non-paymentby providinga free 'social' connection only once. In 1997,it was estimatedthat SODECI carriedout 17,000forced disconnections, and in some of SODECI's areas of operation up to 20 % of connections were reported to be inactive in 2002 (Tremolet et al. 2002). This evidence of high levels of disconnections calls into question the

conventional wisdom that, as the poor pay heavily for water if they are outside networked services (in terms of time and/or high prices from water

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

521

vendors), their willingness and ability to pay for a network connection is relatively high. In reality the poorest may be adversely affected as a tolerance of illegal connections, which could constitute a progressive subsidy,6 has been replaced by high levels of disconnection for non-payment. Although there is little technical data, researchers found that almost everyone agreed that water quality had improved in Guinea after privatisation. Customer service also improved (Menard & Clarke 2002b). In Gabon, targets regarding quality and sanctions were left vague, and were still not in place five years after the start of the contract. However, researchers consider that the water is clearer (with less turbidity) in Libreville but this is not guaranteed throughout the country (Tremolet & Neale 2002). In Senegal, SdE has exceeded targets for water quality since 1999 and customer service has improved (Tremolet et al. 2002). In C6te d'Ivoire, the utility SODECI was reported to be providing high quality water in the early I98os, and met 99 % of WHO water standards in 1997 (Menard & Clarke 2000a). However, in 2002 it was reported that performance had begun to decline and a third of the production centres, many of them in the interior, no longer met WHO standards (Tremolet et al. 2002). All theprivatised utilitiesrecorded profit.In Guinea, despite disappointing a results according to a number of criteria above, the company, SEEG, still made a profit. The financial position of the private operator improved rapidly as a result of improvements in billing and large increases in tariffs. In 1996, the company made profits of$3.2m (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Gabon, turnover has risen and since its first year of operation, SEEG has paid dividends to its shareholders. In 2000, the company reported a profit of $6.89m and in 2001 this rose to $9.67m. Dividends rose from 6-5 % of the share price in the first year to 20 % in 2ooo (Tremolet & Neale 2002). In Senegal financial results are not available (as the company is not listed on the stock exchange), but they are reported to be disappointing due to demand falling below projections, although the company is now posting stable profits (Tremolet et al. 2002). In C6te d'Ivoire, the utility SODECI has remained profitable since 1986 and profits were approaching $4m in 1996 (Menard & Clarke 2oooa). Recently, however, revenues have been stagnating and profits have been reduced. The state remains a bad payer and collection rates have gone down with the recent economic crisis (Tremolet et al. 2002). and Regulation competition Unlike, for example, telecommunications where technological advances have increased competitive pressures, the supply of water has many of the

522

KATE

BAYLISS

characteristics a naturalmonopoly, due to the expense of transporting of or duplicatingof network supplies.Network industriesin the region are small, and so even yardstickcompetitionwithin a countryis not viable. In the case of Gabon, the electricityand water suppliesare bundled together to (orat leastwere not unbundledpriorto privatisation), ensurethat the enwas of sufficientsize to be of interestto investors.In C6te d'Ivoire, terprise the same parent company, Saur, owns both the water and the electricity utilities.As there is little scope for competitionin the water sector,effective regulationis essential.However, the experienceof the case studycountries shows that this has been difficult. The inabilityof regulatorsto enforce complianceon privatecompanies is a widespreadweaknessof privatisation worldwide.However, in poorer countries,where companies are operatingmonopolies in the delivery of water - a basic need for all - and often with support from international donors, regulatoryfailingsare of greater concern. In many countriesthe weak regulatorycapacity is compounded by limited investor interest. In circumstanceswhere the governmenthas gone to considerablelengths to attract investorsyet only one or two bids are received, the threat of retenderingthe contractin the event of non-compliancehas little credibility. Weak capacity in the regulatorhas been partly responsiblefor water levels. Accordingto a 1998World prices in Guinea reachingunaffordable Bank report (cited in Menard & Clarke 2000b), audits revealed that the pricingformulaehad been wronglyapplied,resultingin overvaluedtariffs. Because of this and because of the informalprice negotiations,the private operatorwas receivingmore than twice the revenueper cubic metre than was originallyanticipated.The regulatorwas unable to force the utilityto comply with financial reporting requirements, such as separating the company's activitiesunder lease contract and public work activitiesconducted under separatecontracts.Without such separation,SEEG might be able to allocateany cost overrunsincurredin its operationalactivitiesto constructionactivitiesfor which is does not bear commercial risk (Kerf 2000). Weak regulationmade it difficultto assessrequestsfor increasesin the overalltariffandthe sharethatwent to the privateoperator.This created a situationwhere the governmentrespondedpassivelyto proposalsfrom SEEGfortariffincreases, SEEG'scommercialriskwas reducedas there and was effectivelya pass-through costs.Accordingto BrookCowen (I999), on this meant that the contractwas more like a managementcontractthan a lease in terms of the degree of risk transfer,but without the controlsthat are in place with a managementcontract.Furthermore, weak instituthe

tional framework has meant that there has been no independent body to enforce the contracts between the parties involved in the privatisation.

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

523

Instead, disagreements between operator and public sector have had to be resolved at the highest levels of government. Apart from the specific regulatory agencies, the weak judicial system has made it difficult to collect payments from consumers who refuse to pay (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Gabon, many of the contractual details for effective regulation were still not in place some five years after the start of the contract. For example, the contract required that a cost-accounting system be established within the first three years of the contract, but four years later this had not been done, making it difficult to monitor the performance of the company, particularly in the regional centres. Other tasks also remained outstanding: the preparation of an inventory of assets to be returned to the state at the end of the concession was supposed to be completed within 6 to 12 months after signing the contract. Likewise the documents on service quality were still not drawn up. As a result, there were few mechanisms available to the conceding authority to monitor and regulate service quality (Tremolet & Neale 2002). In Senegal, there have been ongoing tensions between the state holding company/regulator and the private operator, contributing to the lessthan-target progress with respect to access and UFW. Tensions persisted because of staff resentment due to the transfer of operational responsibilities to the private operator (Kerf 2000). Although detailed contracts were drawn up, a number of uncertainties led to difficult negotiations between the parties (Tremolet et al. 2002). In C6te d'Ivoire, there have been concerns about the regulator's ability to efficiently monitor SODECI's investment activities. Under the terms of SODECI's contract, projects valued below a certain threshold can be implemented without the need for competitive tenders. The company may then give undue priority to small investments or lose efficiency by dividing large investments into a series of smaller projects to avoid putting out tenders (Kerf 2000). Some evidence suggests that SODECI has been able to earn excessive profits on infrastructure-related activities (Menard & Clarke 2000a). SODECI's contract does not contain precise performance targets, and the company does not submit information on its performance to the conceding authority at regular intervals. SODECI is supposed to submit annual reports about its activities, and is liable to pay sanctions for failing to meet such performance targets, but has paid no penalties (Tremolet et al. 2002). The large number of public agencies involved in the sector with overlapping responsibilities have made it easier for SODECI to conceal information. Furthermore the system for conflict resolution as well as conflicts between ministries have increased the risk that the private sector would capture rents (Menard & Clarke 2000a).

524

KATE

BAYLISS

In the lease contracts described above, the government has to work closely with the private operator, both to oversee the company's operations and to carry out investment and maintenance in the water sector. Where this relationship is uncooperative, monitoring and investment activities suffer. Both Guinea and Senegal have experienced problems with poor coordination between the operational and investment activities, as well as disputes over the exact scope of maintenance and investment responsibilities and lack of accountability for overall performance. In Guinea, government and operator blame one another for the slow progress of investment (Brook Cowen 1999). The interaction between private water companies and their international parent can be difficult to regulate and may have an adverse impact on competition. In Guinea the parent companies of the private utility SEEG, Vivendi and Saur, provided technical assistance to SEEG for which they were paid 2 % of SEEG's revenues. SEEG also carried out maintenance and bid on construction contracts, but the company failed to produce separate accounts for different functions, even though these were required by the contract (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Senegal, the water company SdE has extensive transactions with its parent, Saur. At the start of the contract, when SdE was setting up computer systems and equipment, these were procured using SAUR's purchasing systems, and many purchases are still centralised via SAUR's headquarters. Most of the work for the installation of new connections was contracted to SdE through a separate contract, preventing the participation of local firms that could have competed. SdE was granted exclusivity over urban services and has obtained contracts for other activities. Thus construction companies which used to provide services to the state utility, SONEES, have been squeezed by SdE (Tremolet et al. 2002). Risk transfer Lease contracts in the water sector are designed to ensure that the risk levels that private firms face are not so high that they will be put off investing. Private operators are usually invited to take over responsibility for operating and managing the network, but are not required to invest in the infrastructure. Contracts are designed to minimise exposure of investors to commercial and currency risk. With the privatisation in Guinea, for example, it was assumed that no investor would want to take on investment and debt service risk, so a lease contract was adopted where SEEG assumed responsibility for operation and maintenance and renewal of small pipes. The risk exposure for SEEG was further reduced by the weak

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

525

regulatory capacity of the government, as the company has been able to increase its remuneration, for example to cover increases in costs, with little pressure to account for rises. In C6te d'Ivoire, the contract with SODECI was renegotiated in 1987, and the government tried to persuade the company to take on a full concession and thereby assume some responsibility for investment and debt service. SODECI refused. As a result, the new contractual arrangement gave SODECI planning responsibilities, and thus a large degree of control over investment, but it remains a lease because SODECI does not commit its own resources to implement the investment programme and to cover debt service charges; it therefore does not bear any investment-related risks (Kerf 2000). A major constraint facing investors in SSA is the declining value of the domestic currency. Where inputs are in foreign exchange and receipts in domestic currency, investors are vulnerable to considerable exchange loss. In order to address this major deterrent to foreign investment, contracts are devised to ensure that the currency risk is passed on to the government or to the consumer. In the energy sector, dollar-based power purchase agreements between the investor and the electricity utility (underwritten by a government guarantee) are common. In the water sector, contracts have provided for renegotiation of the operator's fixed fee on a number of grounds, including the value of the exchange rate. Contracts may also be based in dollars (as in Tanzania), or provide an Automatic Tariff Adjustment (as in Ghana), whereby falls in the currency value may be passed on to the consumer in the form of higher domestic prices. While these contractual arrangements ensure that the investor faces minimal currency risk, they actually fail to reduce the risk. They may even create a moral hazard, in that the investor has no incentive to contain currency exposure as payment is reimbursed. In the Asian energy sector, state electricity utilities became saddled with unsustainable debts as a result of payments due under power purchase agreements following currency devaluation (Bayliss & Hall 2000). The same may happen with the water sector. Privatisation fails to address the need to identify alternative financing arrangements. The roleofpolitics One of the core objectives of privatisation is to reduce the level of political interference in the operation of an enterprise or sector. However, political influence is to some degree inevitable in the operation of the water supply. From a welfare and social perspective the government has a responsibility to ensure that the poor have access to water. Pricing cannot be left to the

526

KATE

BAYLISS

'market' as there is not one. Furthermore, the designs of lease contracts are usually such that the government has to work with the operator on extension and maintenance of infrastructure, which means that the public sector is closely involved in the operations of the water sector. In the case studies, the influence of politics appears to have waned in some cases but not in others, suggesting that de-politicisation is not a guaranteed outcome of privatisation. The financial well-being of the water sector in many countries has been undermined by the non-payment of water bills by government agencies. After privatisation, government agencies in Senegal and Gabon now do pay their bills, while in Guinea and C6te d'Ivoire they do not. In Gabon the government continued not to pay for two years until a debt moratorium was signed in I999, whereby the government agreed to pay a proportion of its debt owed to SEEG each month. The state has since paid its bills regularly (Tremolet & Neale 2002). In Guinea and C6te d'Ivoire, however, political influence remains substantial. For the first two years of the lease, under donor pressure, the government of Guinea paid its bills regularly. But, in 1991, the government collection rate fell to less than 50 % and then dropped further to close to Io % in 1993. When government failed to pay, the private operator withheld its rental payments due to the government, thus restricting scope for future investment. The private operator in Guinea, SEEG, was allowed to disconnect government agencies that failed to pay. However, it did not. This was in part because it wanted to keep on good terms with the government that was operating in its interests. SEEG was trying to get the government to approve larger price increases and the government was represented on the board of SEEG. The absence of an independent judiciary in Guinea meant that even if disputes were resolved it would not be possible to force the government to comply. As a result, problems were resolved through informal negotiations. Thus outcomes were unpredictable, depending on key individuals, and relations between the private operator and government were tense (Menard & Clarke 2ooob).

EMERGING

LESSONS

Three main points emerge from the above discussion. First, the impact of privatisation depends on the initial state of the enterprise. Second, regulation has proved extremely difficult even where regulatory capacity is relatively advanced. Third, privatisation has been constrained by the lack of investor interest in the water sector in the region.

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

527

The case studies reveal that privatisation has had limited impact on the performance of the water utilities in Guinea, Gabon and Senegal. Guinea, which was in crisis before the start of the contract, remains in poor shape. The gains that have been achieved are in terms of short-term profitability (rapid increase in metering and profitability), or are due to investment by donors. On the other hand, both Senegal and Gabon were well run before privatisation and continue to be so. In terms of organisational structure, changes have not been dramatic. In Guinea, 'although performance has improved, many of the changes have been quite modest, especially considering the poor initial performance of the sector' (Menard & Clarke 2000b). In Gabon, the organisation of SEEG was reported to be quite similar at the time of the research to the structure at privatisation (Tremolet & Neale 2002), and in Senegal, after privatisation, company management and staffing remained stable and no major restructuring was deemed necessary (Tremolet et al. 2002: 78). Furthermore, in C6te d'Ivoire, performance standards have started to slip due to developments in the country's wider economic circumstances. This suggests that little can be expected of privatisation perse in terms of its impact on an enterprise. It is what public and private enterprises have in common within a country that determines performance, rather than the nature of ownership. Second, the failure to comply with regulation and the limited disclosure by private firms have been a major weakness of the privatisation contracts that have taken place. While firms may claim major successes, it is not always possible for observers - or even regulators - to validate these claims because of the limited availability of information. Regulators appear to have little to hand by way of sanctions against private operators. Furthermore, the threat of further eroding investor confidence makes it difficult for regulators to take action against MNCs. Asymmetries in capacity and resources further undermine the effectiveness of water regulation in SSA. Given the widespread weakness in regulation of the water sector in SSA (and elsewhere), some alternative means of accounting for the performance of MNCs in the water sector in poor countries is required. The conventional approach to regulation pre-supposes a capacity and a bargaining position which is often absent in low-income economies. Where MNCs are supplying water to some of the poorest people in the world, it is important to know that consumers are not being exploited. Some international disclosure requirements could be placed on water providers in the poorest countries. Third, in much of SSA it has been difficult to rouse investor interest. This is in part because of the problem of reconciling the conflict between the profit motive and the provision ofa social service. Such incompatibility

528

KATE BAYLISS

has recently been highlighted by water companies themselves, as for example in the withdrawal ofBiwater from Zimbabwe. Stafffrom Vivendi participated in a conference in Kampala in 2001, providing an illuminating insight into privatisation from the firm's perspective. According to the participants, private firms need to be able to generate a 'fair' profit (quotation marks added). This then limits investment to 'big cities where the GDP/ capita is not too low'. Private firms are available inasmuch as the project is bankable, and bankability comes from 'guarantees securing the flow of payments by the municipalities or Governments', and/or 'sufficient and assured revenues from the users of the service' (Bourbigot & Picot 2001). Similarly, in a recent presentation to the World Bank, J. F. Talbot (2002), CEO of Saur, one of the major investors in the water sector in SSA, raised a number of concerns regarding investment in the water sector in developing countries. He spoke of a marked increase in risk for private operators, particularly in developing countries, as well as 'an emphasis on unrealistic service levels', leading to 'limited interest in the market'. He went on to say that subsidies (which are used in industrialised countries) are needed, as service users cannot pay for the level of investment required. These remarks from investors in SSA make it clear that private firms will only be interested in profitable investments, where either the government or consumers can pay enough to generate a commercial return. Private firms do not bring finance but seek profit. Capital investments cannot be self-financing, as consumers cannot pay tariffs sufficient to finance the levels of investment required in water infrastructure. Without state (or donor) financed subsidies, it may be difficult to attract investors into lowincome economies. Africa is not an attractive investment for MNCs at present,7 and this is not just in water. In the energy sector, companies have been cutting back on developing-country activities as financial backers have imposed greater scrutiny on investments in the light of the Enron crisis. Continuing to push privatisation in these circumstances will mean that governments have to offer greater incentives to attract investors. Contracts will have to ensure that less risk is transferred to the private sector and regulation (even if it is in place) will be less enforceable, as the ultimate sanction of re-tendering will not be a valid option. Such measures may considerably undermine the benefits that privatisation is supposed to achieve.

Although widely promoted across SSA, privatisation is difficult and costly to achieve in practice and the benefits may be limited. The discussion

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

529

above shows that privatisation is not a miracle cure for poor enterprise performance. It is easier to implement where a utility is performing well, while there will be less investor interest in a poorly performing utility, so that more concessions will be needed and fewer gains may be expected. Privatisation is just one of a number of reform options and needs to be considered as such. The starting point for reform should be an assessment of objectives and an evaluation of options. Privatisation may bring little from investors in the way of finance for much-needed investment in infrastructure. Much of the investment that is associated with privatisation comes from donors through the release of aid funds, and this distorts the perspective of the policy. Governments have little alternative but to privatise. Meanwhile, privatisations have been delayed for years due to weak investor interest as well as domestic opposition to the process. This 'limbo' phase can itself be destructive in terms of staff morale and access to resources. This case study in water shows that the nature of ownership does not necessarily indicate how an enterprise will perform, and privatisation fails to deal directly with some of the fundamental constraints facing utilities in SSA. While it may bring improvements in managerial efficiency, it does not bring finance on the scale needed to finance the investment required. It fails to address the problem posed by declining currency values and the need for greater domestic financing of investments. The case studies show that privatisation has not always managed to overcome the non-payment of bills by government or the reluctance of governments to increase prices. Finally, it is not clear that privatisation has improved the access of the poor to safe water. Rather than focusing reform efforts on the detail of privatisation, greater insight is needed into how and why effective performance is achieved in some circumstances and not others. Policy makers would benefit from more impartial research into cases where the economic, political, social and historical factors have created and sustained effective water polices, regardless of ownership.

NOTES I. The term Private Sector Participation (PSP) is also used, interchangeably with privatisation, to refer to private sector inputs into service delivery. 2. African Economic Outlook - Country Studies: Cameroon OECD, 31.1.2002. www.oecd.org 3. 149 % of the Ksh 12.7 billion ($169 million) collected over the period. 4. http://www.sadcreview.com/sectoralpercent2oreportspercent2o2ool/water.htm 5. http://www.newafrica.com/investment/projects/countries.asp?countrylD=7 6. Research in Colombia estimated that non-payment or illegal connections accounted for 24 % of subsidies in water and sanitation, and this subsidy was highly progressive with more than 73 % of the subsidy benefiting households in the five poorest deciles of the income distribution (cited in Estache et al. 2000).

530

KATE BAYLISS

7. Analysts have suggested that one of the reasons why the parent company of Saur, the French conglomerate Bouygues, has had difficulty in selling Saur is that a large part of Saur's customer potential is in Africa (Weimer 2002).

REFERENCES Ariyo, A. & A. Jerome. 1999. 'Privatization in Africa: an appraisal', WorldDevelopment 1: 201-13. 27, Bayliss, K. 2001. 'Privatisation of electricity distribution: some economic, social and political perspectives', University of Greenwich: Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), Report for Public Services International. Bayliss, K. 2002. 'Privatisation and poverty: the distributional impact of utility privatisation', Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics73, 4Bayliss, K. & D. Hall. 2000. 'Independent power producers: a review of the issues', University of Greenwich, PSIRU. www.psiru.org Bayliss, K., D. Hall & E. Lobina. 2002. 'Water Privatisation in Africa', University of Greenwich, PSIRU. www.psiru.org Boland, J. & D. Whittington. 2000. 'Water tariff design in developing countries: disadvantages of increasing block tariffs (IBTs) and advantages of uniform price with rebate (UPR) designs', Washington, DC: World Bank Water Resources Management. Bourbigot, M.-M. & Y. Picaud. 2001. 'Public-private partnership (PPP) for municipal water services', regional conference on The Reform of the Water Supply and Sanitation Sector in Africa, Kampala. Brook Cowen, P. 1999. 'Lessons from the Guinea water lease'. Washington, DC: World Bank Public Policy for the Private Sector, Note No. 78. Brook, P. & A. Locussol. 2001. 'Easing tariff increases: financing the transition to cost-covering water tariffs in Guinea', in P.J. Brook & S. M. Smith, eds., Contractingfor aid public services: output-based and its applications. Washington, DC: World Bank, ch. 3. Castel-Branco, C., C. Cramer & Degol Hailu. 2001. 'Privatisation and economic strategy in Mozambique'. Helsinki: UNU/WIDER Discussion Paper 2001/64. www.wider.unu.edu Estache, A., A. Gomez-Lobo & D. Leipziger. 2000. 'Utilities "privatisation" and the poor's needs in Latin America: have we learned enough to get it right?'. Conference on Infrastructure for Development: Private Solutions and the Poor. London, 31.5-2.6.2000. Hall, D. 2002. 'The water multinationals 2002 - financial and other problems'. August 2002 PSIRU report for PSI. http://www.psiru.org/reports/2002-o8-W-MNCs.doc Hemson, D. & H. Batidzirai. 2002. 'Case study: Dolphin Coast water concession', Loughborough University, Water Engineering Development Centre (WEDC), Public Private Partnerships and the Poor Series. Kayizzi-Mugerwa, S. 2002. 'Privatisation in sub-Saharan Africa: factors affecting implementation'. Helsinki: UNU/WIDER Discussion Paper No. 2002/12. Kerf, M. 2000. 'Do state holding companies facilitate private participation in the water sector?'. Washington, DC: World Bank, Private Sector Development, Policy Research Working Paper 2513. Klahanie, P. & A. Tanner. 2001. 'Overview of the Uganda water sector reform, focussing on the urban water and sanitation sub sector reform study', regional conference on The Reform of the Water Supply and Sanitation Sector in Africa, Kampala. Megginson, W. &J. Netter. 2001. 'From state to market: a survey of empirical studies on privatisation', Journal of EconomicLiterature 321-89. 39: Menard, C. & G. Clarke. 2oooa. 'Reforming water supply in Abidjan, C6te d'Ivoire: a mild reform in a turbulent environment'. Washington, DC: World Bank Country Economics Dept. Papers, No. 2377. Menard, C. & G. Clarke. 2ooob. 'A transitory regime: water supply in Conakry, Guinea'. Washington, DC: World Bank, Development Research Group. Policy Research Working Paper 2362. NamWater. 2000. NamwaterAnnual ReportI999-2ooo. Windhoek: Namibia Water Corporation Ltd. Renzetti, S. 2000. 'An empirical perspective on water pricing reforms', in A. Dinar, ed., The Political Economyof WaterPricingReforms. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press for World Bank, 123-40. Samuel, B. 1999. 'A new look at African privatisation'. Washington, DC: IFC Corporate Finance Services Department. Talbot, J. F. 200oo2. 'Is the water business really a business?', World Bank Water and Sanitation Lecture Series, 13 February. http://www.worldbank.org/wbi/B-SPAN/docs/SAUR.pdf

WATER

PRIVATISATION

IN AFRICA

531

Temu, A. & J. M. Due. 1998. 'The success of newly privatized companies: new evidence from Studies 19, 2: 315-41. Tanzania', Canadian Journal of Development Tremolet, S. 2002. 'Rural water service: is a private national operator a viable business model?'. Washington, DC: World Bank, Public Policy for the Private Sector, Note 249Tremolet, S. &J. Neale. 2002. 'Emerging lessons in private provision of infrastructure services in rural areas: water and electricity in Gabon'. Washington, DC: World Bank PPIAF, Final Report, Environmental Resources Management. Tremolet, S., S. Browning & C. Howard. 2002. 'Emerging lessons in private provision of infrastructure services in rural areas'. Washington, DC: World Bank PPIAF, Final Report, Environmental Resources Management. UNICEF. 2002. Background statistics for United Nations Special Session on Children, May 2002. http://www.unicef.org/specialsession/about/sg-report.htm van de Walle, N. 1994. 'The politics of public enterprise reform in Cameroon', in B. Grosh & R. in Mukandala, eds., State-Owned Enterprises Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. Wateraid. 2002. 'Private sector participation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania'. London: WaterAid Tearfund Case Studies on Private Sector Participation. http://www.wateraid.org.uk/site/in_ depth/current_research/4I1 .asp Weimer, N. 2002. 'Rwe probably not interested in Bouygues's Saur', Bloomberg News, 6.5.2002. Weissman, R. 2002. 'The anatomy of a deal: a close look at the World Bank's plans to privatise Ghana's water system', MultinationalMonitor23, 9. Werchota, R. 2001. 'Sustainable service provision for the urban poor', Paper presented at the 27th WEDC conference, Lusaka, Zambia. World Bank. 2001. Project Information Document, Report No. PID98Ig, Guinea- Third WaterSupply and SanitationProject,Supplemental Credit.Washington, DC: World Bank. World Bank. n.d. Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). www.ppiaf.org

and Newspapers Agencies

(New York); Dispatch online (East London); Africa Energy& Mining (Paris); AfricaNews; AP Worldstream The East African (Nairobi); FT Energy Newsletters; Panafrican News Agency (PANA); Reuters; ZimbabweIndependent (Harare).

Вам также может понравиться

- GrahamAllisonThe CubanMissileCrisisДокумент28 страницGrahamAllisonThe CubanMissileCrisisJonatan BorbaОценок пока нет

- Regional Solutions Regulating Recruitment Protection African Migrant Workers Gulf Middle East ECDPM Discussion Paper 292 2020Документ28 страницRegional Solutions Regulating Recruitment Protection African Migrant Workers Gulf Middle East ECDPM Discussion Paper 292 2020최두영Оценок пока нет

- Possibility and Challenge of Smart Community in Japan: SciencedirectДокумент10 страницPossibility and Challenge of Smart Community in Japan: Sciencedirect최두영Оценок пока нет

- ROSCA Nairobi SiwanДокумент33 страницыROSCA Nairobi Siwan최두영Оценок пока нет

- Nomura RegenerativeДокумент33 страницыNomura Regenerative최두영Оценок пока нет

- 10 1111@muwo 12316Документ16 страниц10 1111@muwo 12316최두영Оценок пока нет

- Ghana Fisheries ProfileДокумент15 страницGhana Fisheries Profile최두영Оценок пока нет

- Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development - Evidence From A Field Experiment in KenyaДокумент40 страницSavings Constraints and Microenterprise Development - Evidence From A Field Experiment in Kenya최두영Оценок пока нет

- Urban Regeneration, Governance and The State: Exploring Notions of Distance and ProximityДокумент19 страницUrban Regeneration, Governance and The State: Exploring Notions of Distance and Proximity최두영Оценок пока нет

- Cracknell KenyaДокумент75 страницCracknell Kenya최두영Оценок пока нет

- Out of Africa MoneyДокумент5 страницOut of Africa Money최두영Оценок пока нет

- Mami WataДокумент19 страницMami Wata최두영100% (4)

- Cold Chain KenyaДокумент4 страницыCold Chain Kenya최두영Оценок пока нет

- China2015 PDFДокумент24 страницыChina2015 PDF최두영Оценок пока нет

- Making States Work State FailureДокумент419 страницMaking States Work State Failure최두영Оценок пока нет

- Making States Work State FailureДокумент419 страницMaking States Work State Failure최두영Оценок пока нет

- FDI Papers Book Length VolumeДокумент244 страницыFDI Papers Book Length Volume최두영Оценок пока нет

- Revisiting Hymer's Political Economy of GlobalizationДокумент42 страницыRevisiting Hymer's Political Economy of Globalization최두영Оценок пока нет

- Making States Work State FailureДокумент419 страницMaking States Work State Failure최두영Оценок пока нет

- Rise of The African Consumer-McKinsey Africa Consumer Insights Center ReportДокумент24 страницыRise of The African Consumer-McKinsey Africa Consumer Insights Center ReportMothish Chowdary GenieОценок пока нет

- Peter Raulwing The Kikkuli Text Master File Dec 2009Документ21 страницаPeter Raulwing The Kikkuli Text Master File Dec 2009최두영Оценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- A Study On Ipo MarketДокумент104 страницыA Study On Ipo MarketJay PatelОценок пока нет

- Bank of Khyber Internship Report For The Year Ended 2010Документ108 страницBank of Khyber Internship Report For The Year Ended 2010Mohammad Arif67% (3)

- GIC Report 2019 20 1Документ84 страницыGIC Report 2019 20 1a aaaОценок пока нет

- Practice Test Mid Term 1Документ9 страницPractice Test Mid Term 1Bob ColtonОценок пока нет

- Phil. Home Assurance Corp vs. CAДокумент1 страницаPhil. Home Assurance Corp vs. CACaroline A. LegaspinoОценок пока нет

- Authority To Sell FORMДокумент2 страницыAuthority To Sell FORMSuzi Garcia-RufinoОценок пока нет

- Ap Workbook PDFДокумент44 страницыAp Workbook PDFLovely Jay AbanganОценок пока нет

- Liquidity of Siddhartha Bank Limited: A Summer Project Report Submitted ToДокумент35 страницLiquidity of Siddhartha Bank Limited: A Summer Project Report Submitted Tosumeet kcОценок пока нет

- Accounting ConceptsДокумент32 страницыAccounting ConceptsSarika KeswaniОценок пока нет

- 123 PDFДокумент3 страницы123 PDFraggerloungeОценок пока нет

- TestДокумент14 страницTesthonest0988Оценок пока нет

- Case 15-5 Xerox Corporation RecommendationsДокумент2 страницыCase 15-5 Xerox Corporation RecommendationsgabrielyangОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Financial Performance Ratios for HP, IBM and DELL from 2008-2010Документ35 страницAnalysis of Financial Performance Ratios for HP, IBM and DELL from 2008-2010Husban Ahmed Chowdhury100% (2)

- Auditing 2&3 Theories Reviewer CompilationДокумент9 страницAuditing 2&3 Theories Reviewer CompilationPaupauОценок пока нет

- Strategic Cost ManagementДокумент71 страницаStrategic Cost ManagementJamaica RumaОценок пока нет

- Bank Marketing 1Документ69 страницBank Marketing 1nirosha_398272247Оценок пока нет

- RATIO HavellsДокумент22 страницыRATIO HavellsMandeep BatraОценок пока нет

- Bank StatementДокумент4 страницыBank Statementuriaswalliser.frnb1.04.4Оценок пока нет

- Itr 2 in Excel Format With Formula For A.Y. 2010 11Документ12 страницItr 2 in Excel Format With Formula For A.Y. 2010 11Shakeel sheoranОценок пока нет