Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs - Alec Hansen

Загружено:

alec_hansen7251Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs - Alec Hansen

Загружено:

alec_hansen7251Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

WHAT MOTIVATES CIVIC ENTREPRENEURS?

Profiles in Co-opetition

By Alec L. Hansen, Ph.D.1

Around the world, the phenomenon of cluster-based economic development is gaining recognition. From Silicon Valley and Connecticut, to Mexico and Morocco, economic development professionals are finding that using the competitiveness framework can revitalize regions and accelerate growth. However, many accounts of cluster development and regional competitiveness skirt around the fundamental driver of successful clusters: the role of the civic entrepreneur. These are the private sector business owners and managers who bring their vision and commitment into the arena of regional cluster development. How can we find them if we are not looking for them? Development planners and government officials who find themselves poised to launch a cluster process often approach the prospect with some trepidation. They read about private sector involvement, even private sector leadership, but then find themselves organizing meetings in which only a handful of participants are actually from the private sector, but which are nevertheless called cluster meetings. Often private sector leaders are propped up as chairpersons of committees that they are not really leading, and they founder in that role, ineffectual and frustrated. When one questions the organizers, one discovers that many of these well-intentioned officials think the notion of a private sector-led process is essentially rhetoric, and that clusters are driven by the usual cast of characters in most economic development programs planners, officials, politicians, consultants and association executives with a few business leaders included to lend legitimacy to the process. Perhaps unconsciously, they dont believe that a busy, profit-oriented business owner would choose to spearhead an economic development initiative in his or her region. Many accounts of clusters around the world gloss over the role of these private sector leaders. This article will attempt to rectify this omission, by focusing on the role of the civic entrepreneur, and considering the motivations of these remarkable individuals. With insights into what can bring out the best in potential cluster leaders, planners hoping to facilitate lasting change in their regions will be better able to support these civic entrepreneurs the individuals whose actions are ultimately most likely to result in a transformation of a regions economy.

President of the Economic Competitiveness Group, Inc., with research assistance from Kelly Cronen. Originally appeared in March-April 2002 edition of Industry Focus Magazine, Mauritius.

Copyright Alec L. Hansen 2002

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

Civic Entrepreneurs are generally CEOs and business owners, but can also be government officials, educators, union officials, or non-profit leaders. When others see problems and gridlock, civic entrepreneurs see opportunity and mobilize their communities on a path forward.2 The story of the rise of wine industry in California exemplifies the classic role of a civic entrepreneur.

How a Civic Entrepreneur can Transform a Region and an Industry

Robert Mondavi is the founder of the Napa Valley wine cluster in California, just north of San Francisco Bay. The Mondavi family was a well-established wine-making family in Northern California, owning thousands of acres. Their wines were what could best be described as jug wines, as were the other wines produced across the United States at that time. In 1962, Robert Mondavi took a trip to Europe where he was inspired by the European process of making wine. He felt that the Napa Valley region, with its intense sunlight tempered with fog near the harvest season, could also be a premier winemaking region, but that the approach to making wine would need to be completely transformed. Mondavis older brother Peter did not share his vision, and in 1966 the two split. Peter kept the estates and wineries, while Robert bought 160 acres in Napa Valley a tiny plot in a commodity business where quantity, not quality, was the traditional route to profits. Roberts goal, however, was to combine European craft and tradition with the latest American technology, management, and marketing know-how. To establish himself in the first year, he worked closely with top grape growers in the area. In doing this, he began to change the relation between growers and producers, opening up and transforming the grape growing industry. He introduced educational programs for the growers that would allow growers to understand the correlation between the quality of the grapes and the quality of the wine.3 He was also devoted to research and development, and wanted the winery to become a pioneer in research and a gathering place for the greatest minds in the industry. Mondavis vision was not just to produce the best wine in the world, but to ensure that wineries all over Napa Valley were operating at that level, because a single winery has a difficult time making a name for itself, as wine, like so many products, is known by region. His open and inclusive style was not a charitable activity, but motivated by his self interest: how could he produce and market a premier product unless growers of grapes, suppliers of barrels, label producers, agronomists in short the entire cluster surrounding him, were operating at his level? Over the next decade, his techniques spread to other winemakers, and by 1976, Mondavi and his colleagues were ready. On May 24 of that year, a few cases of wine from Napa

Henton, Melville and Walesh, Grassroots Leaders for a New Economy: How Civic Entrepreneurs Are Building Prosperous Communities, Josse Bass Public Administration Series, 1997.

2

Harvests of Joy: How the Good Life Became Great Business, by Robert Mondavi; Harcourt, Brace & Co 1998, Page 100.

3

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

were entered in a legendary blind wine-tasting competition in Paris, organized by the famed wine merchant Steven Spurrier. When the results were tallied, Napa wines had swept the top rankings. Among the white wines, Chateau Montelenas Chardonnay captured 1st place, with other Napa wines capturing 3rd and 4th places as well. Among the red wines, Stags Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet captured first, placing ahead of Chateau Mouton-Rothschild. Such a strong showing from a previously unknown region was a phenomenal surprise. The French monopoly [on fine wines] was crushed permanently.4 In an ironic twist of fate, the shipment of crates from the Mondavi winery were delayed en route, and arrived too late to be judged. However, Mondavi had achieved his goal the recognition of Napa Valley as a premier wine-making region. Robert Mondavi wines won numerous awards in subsequent years, and his Special Reserve now sells for $200 per bottle. More importantly, the economy of the entire region has been transformed, with a quality of life unsurpassed among agricultural regions in the world.

Photo: Robert Mondavi

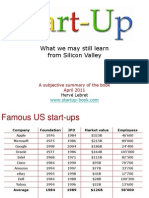

Mondavis vision, combined with the opportunity afforded by his dispute with his brother, was responsible for a revolution in an agricultural region. Are other industries similarly susceptible to the actions of a few individuals? The Interaction between Visionary and Catalyst The arrival of a leading researcher in 1956 to Palo Alto, California was another random catalytic event, one that helped tip the region around Stanford University from a panorama of apricot orchards to a landscape dotted with Apple Computers, silicon chip fabricators and software powerhouses: Silicon Valley. The visionary in this story was Fred Terman, Dean of Stanford University's Department of Electrical Engineering. His vision of close industry-university partnerships had already encouraged several spinoffs, including William Packard and David Hewlett, but the Valley had not yet taken off.

Ronn Wiegand, as quoted in The Day California Wines Came of Age, by Thane Peterson, in the Moveable Feast column in BusinessWeek Online, May 8, 2001.

4

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

The big break came when Terman convinced Dr. William Shockley, the inventor of the electronic transistor, to come to Palo Alto, rather than MIT, where the leading electronics researchers at that time were based. In 1956, Shockley Transistor Laboratory was established in the new Stanford Industrial Park, with a brain trust of young engineers from MIT and other East Coast universities. Their work was set to revolutionize the electronics industry, allowing the shift from bulky vacuum tubes to tiny circuits embedded in silicon. However, frustrated and alienated by Shockleys caustic personality, eight of the brightest of these electronics specialists left Shockley to form Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation. It became the first firm to manufacture exclusively in silicon and rapidly developed into one of the largest firms in the California electronics industry. More than 70 high-tech companies, such as Intel and Motorola, are direct or indirect descendants of Fairchild.5

The proposition behind clusterbased economic development is that there are potentially dozens of Robert Mondavis and Fred Termans in a given region leaders who have vision and access to resources that can transform their region, but who lack a catalyst.

Again, it was a combination of vision Termans and a catalyst the arrival of Shockley and the fact that he couldnt hold on to his talented colleagues that spawned the economic miracle that became Silicon Valley.6

Is it possible to replicate Mondavis success in other regions?

Robert Mondavi and Fred Terman were probably not familiar with the term cluster they simply implemented a vision for their regions. The proposition behind clusterbased economic development is that there are potentially dozens of Robert Mondavis and Fred Termans in a given region leaders who have vision and access to resources that can transform their region, but who lack a catalyst to get them started.7 Where a natural catalyst is absent, a cluster-based approach, mobilized by the economic development community, can act as the catalyst, propelling these civic entrepreneurs to implement their dreams. Are there examples of such artificially accelerated clusters? What is the role of the civic entrepreneur in that environment? There are in fact numerous examples of successful entrepreneurs who made this transition as a result of a cluster development program in their region.

Mackun, Paul. "Silicon Valley and Route 128: The Two Faces of the American Technopolis" Online: Silicon Valley and IT History Site. Feb 1, 2002. Available at: http://www.netvalley.com/archives/mirrors/ sv&128.html.

5 6 7

Of course, other individuals and events contributed as well, but this was a defining moment.

What would have happened if Robert Mondavi had patched up his argument with his brother? Its possible that Napa Valley would still be producing jug wines. The buy-out agreement, which put monetary resources in the hands of a man with a vision, was a catalytic event for Napa Valley and the California wine industry. 4

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

Arizona Alan Hald is a co-founder of MicroAge, a Fortune 500 company based in Phoenix, Arizona that grew from a single a single location in 1976, selling hobby kit computers, to a systems integration powerhouse with over $4 billion in revenues. Although his company was successful, Hald felt that Arizona had become a branch plant state, attracting mainly low-wage, low-skill jobs. Without a radical new approach, the state would be unable to shake off a recent savings and loan scandal, whose impact on the real estate sector had crippled the economy. When Hald learned about a new cluster-based economic development initiative in the state, he became involved, and eventually was nominated to serve as co-chairman, along with then-Governor Symington, of the Governors Strategic Partnership for Economic Development (GSPED). Hald has served in this position tirelessly for nearly ten years, helping shape the states responses to education issues, the New Economy, and the challenges of developing eleven industry clusters. When asked in 1998 why he found the time and energy to attend so many meetings, he replied at every one of these events I also find something that helps my company an idea, a new contact, a possible connection. But there is a certain part of me that wants to do good I derive satisfaction from what were accomplishing here. If my children end up going to college in Cambridge, Massachusetts or Cambridge, England, I want them to feel that they can come back to Arizona and find a thriving economy and dynamic opportunities, as I have. I dont want my company to be the exception. Thats what keeps me going. Self interest, melded with the desire to build a strong regional economy, motivates this civic entrepreneur. The Pharmaceutical Industry At a recent conference hosted by the Council on Competitiveness in Washington, D.C., a discussion emerged on the motives of civic entrepreneurs and the question arose Why would a civic entrepreneur choose to be involved in a cluster development process? Ray Gilmartin, CEO of Merck & Co.,8 took the microphone, and gave an impassioned answer. I enjoy this work, but I dont do it out of charity. I do it because I think it will profit Merck. For example, I used to pay attention to my accounting staff when they told me that the most cost-effective place to locate our research laboratories is right next to our headquarters in Whitehouse Station, New Jersey. However, since learning about clusters of innovation, I am now building new research labs in San Diego and Southern Connecticut, so that my researchers can take full advantage of the climate of innovation in those regions. Apples in Cuauhtmoc, Mexico Oscar Armando Corral Perez owns more apple trees than anyone in the world. His orchards in Cuauhtmoc, a rural area in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, have

Gilmartin is President and CEO of Merck & Co., one of Americas leading pharmaceutical companies, based in Whitehouse Station, New Jersey. He is currently serving as Chairman of the Council on Competitiveness.

8

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records, and his delicious, high quality apples are recognized throughout Mexico. However, he knows that in order to successfully export to the United States, he will need even higher quality standards, and that his region will need to be recognized, not just his orchards. When a group of consultants from Chihuahua City9 offered their cluster development methodology, he jumped at the opportunity, and was soon asked to become co-chairman of the cluster in Cuauhtmoc.

Photo: Inset:

Oscar Corral (left) showing his packaging plant to a delegation from Jordan. One of Corrals many apple brands.

Corral has worked with his fellow apple farmers on a variety of joint initiatives. Together they are producing nets to protect their fruit from hail near harvest time, to develop brand names that can be used by all producers in the region, and to involve researchers from the local university to help improve quality. While this initiative is less than two years old, it is already helping to raise incomes and employment in Cuauhtmoc. An already successful businessman is poised to move his company to the next level by leading a regional initiative. Alonso Ramos, an economic advisor to Mexicos President Fox, reports that Corrals activities have reversed the actitud de derrota (mentality of defeat) which has characterized the region until recently. The intervention of government officials is increasingly seen as something less necessary (and even annoying). Other leaders have emerged to launch production and exports of non-traditional products such as strawberries and mink pelts, leading to diversification of the economy. The success of la initicativa privada in Cuauhtmoc has also stimulated a similar approach in Delicias, the traditional rival city.

9

Alderete y Socios, Chihuahua, Mexico. www.aldereteysocios.com 6

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

Do civic entrepreneurs work only outside government? In the mid-1990s, Campeche was a low-performing state in southeastern Mexico, not far from Cancun, but more concerned about letting its sleepy economy go the way of nearby Chiapas. A dozen private sector leaders, including a baker, a hotel manager, and an architect, learned about the cluster process following a trip to Chihuahua, and determined to launch a similar process in their state. Over a two-year period, they energized new strategies and new thinking throughout the state, and the results were tangible: 12 new factories where none had existed before, a new direction for their declining shrimp industry, and high-growth exports of nontraditional fruits, vegetables, and tropical nutritional supplements. The citizenry of Campeche could have reacted to this new agenda with suspicion and resentment, shunning the visionary program of these private sector leaders. On the contrary, they saw it as such a refreshing alternative to business as usual in state government, that they elected several of these entrepreneurs to public service. The baker is today the Secretary of Economic Development, the hotel manager is Secretary of Tourism, and the architect is Governor. Want to launch a cluster process? Give civic entrepreneurs a genuine role For every account of cluster development processes supporting private sector leaders as they transform their regions, there are an equal number of well-intentioned efforts that started off with similar enthusiasm, but led nowhere. The difference often lies in the role in which private business leaders have been cast. If cluster organizers see private sector leaders as symbolically important, but too busy to get deeply involved, or only motivated by charity, cluster initiatives will be run by cluster organizers not a bad outcome, if the organizers are talented, but seldom transformational. What if cluster organizers push the envelope, and genuinely trust that a handful of private sector leaders in their region are potential Robert Mondavis? The organizers would become a catalyst for action, using cluster facilitation methods to craft events and structures that will convince industry leaders to take the plunge. Essentially, the cluster framework allows entrepreneurs to commit to realizing their economic vision sometimes a vision they have held close to the vest for many years, but had always been reluctant to implement for fear that the risks were too great. Industry leaders will commit to the process when they are convinced that their time will not be wasted, and that their leadership will be acknowledged rather than subverted by a state-driven, political agenda. By respecting the true motivation of these civic entrepreneurs, their sustained participation, and hence the successful transformation of the region, is more likely. Ultimately, most private sector leaders are willing to invest their time in cluster development because of two intertwined motivations: a drive to make the region, and hence their company, an industry leader (the profit motive), and

What Motivates Civic Entrepreneurs?

a desire to make the region sufficiently prosperous and economically diverse that his or her children will have desirable opportunities to return to after college. Cluster organizers need to be willing to make room for local business leaders, and trust the vision and initiative of these civic entrepreneurs. When private sector leaders learn about the concepts and sense tangible support from cluster organizers, the vision will unfold organically and powerfully, from the ground up.

Dos and Donts for Launching a Cluster

DONT

Resist the profit-motivated self-interest of the entrepreneur dont view contribution as charity work Over-steer the process

DO

Acknowledge that self-interest is needed and welcome in order to transform the regions economy Allow for an open-ended process, with the private sector leaders driving, and donors, government and academia supporting Place equal or greater emphasis on generating detailed, fact-based strategies and action plans for individual clusters, with strong champions. Strong clusters will make the Councils more practical. Start with shorter, executive-style reports, saving funds for continuous analysis throughout the project; active clusters have on-going needs for answers to specific questions about best practices and market and technology trends.

Focus exclusively on creation of high-level Council of Competitiveness

Let analysis and report-writing dominate the budget. Too many cluster projects have resulted in a pretty report but no action whatsoever

Вам также может понравиться

- The Enlightened Capitalists: Cautionary Tales of Business Pioneers Who Tried to Do Well by Doing GoodОт EverandThe Enlightened Capitalists: Cautionary Tales of Business Pioneers Who Tried to Do Well by Doing GoodРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Silicon Valley-: Origin of The TermДокумент4 страницыSilicon Valley-: Origin of The TermKanexongОценок пока нет

- The Sustainable Company: How to Create Lasting Value through Social and Environmental PerformanceОт EverandThe Sustainable Company: How to Create Lasting Value through Social and Environmental PerformanceОценок пока нет

- The AtlanticДокумент3 страницыThe AtlanticcorradopasseraОценок пока нет

- National Case Studies on Entrepreneurial Rural CommunitiesДокумент5 страницNational Case Studies on Entrepreneurial Rural CommunitiesPattemОценок пока нет

- Silicon Valley, The Triumph of Technology: Radu Daniela Adina, StudentДокумент11 страницSilicon Valley, The Triumph of Technology: Radu Daniela Adina, StudentDaniela RaduОценок пока нет

- Innovation on Tap: Stories of Entrepreneurship from the Cotton Gin to Broadway's HamiltonОт EverandInnovation on Tap: Stories of Entrepreneurship from the Cotton Gin to Broadway's HamiltonОценок пока нет

- Full Download Solution Manual For International Financial Management Eun Resnick 6th Edition PDF Full ChapterДокумент36 страницFull Download Solution Manual For International Financial Management Eun Resnick 6th Edition PDF Full Chaptersowse.lieutccli100% (18)

- Book Review: The Speed of Trust by Stephen M.R. Covey: Understanding the power of trustОт EverandBook Review: The Speed of Trust by Stephen M.R. Covey: Understanding the power of trustРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Explaining The Growth and Globalization of Silicon Valley: The Past and TodayДокумент49 страницExplaining The Growth and Globalization of Silicon Valley: The Past and Todayerdal karatasОценок пока нет

- Crisis of Character: Building Corporate Reputation in the Age of SkepticismОт EverandCrisis of Character: Building Corporate Reputation in the Age of SkepticismОценок пока нет

- Scott W Downs - Global Culture v6 11-17-14Документ4 страницыScott W Downs - Global Culture v6 11-17-14api-241511116Оценок пока нет

- The Dictatorship of Woke Capital: How Political Correctness Captured Big BusinessОт EverandThe Dictatorship of Woke Capital: How Political Correctness Captured Big BusinessРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (3)

- Globalisation A Converging Commanality CS 3Документ2 страницыGlobalisation A Converging Commanality CS 3Bolang chaiОценок пока нет

- Building Small: A Toolkit for Real Estate Entrepreneurs, Civic Leaders, and Great CommunitiesОт EverandBuilding Small: A Toolkit for Real Estate Entrepreneurs, Civic Leaders, and Great CommunitiesОценок пока нет

- Kucukkaya Evren - Intercultural Management Final AssignmentДокумент13 страницKucukkaya Evren - Intercultural Management Final AssignmentEvren KüçükkayaОценок пока нет

- Deeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven LeadershipОт EverandDeeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven LeadershipОценок пока нет

- 1.3 Entrepreneurial ClassДокумент5 страниц1.3 Entrepreneurial ClassArpit RОценок пока нет

- Bottom of the Pyramid MarketДокумент6 страницBottom of the Pyramid Marketgaia_dharaОценок пока нет

- Solution Manual For International Financial Management Eun Resnick 6th EditionДокумент36 страницSolution Manual For International Financial Management Eun Resnick 6th Editionoleooilbarouche2uv2y100% (46)

- The Cult of the Leader: A Manifesto for More Authentic BusinessОт EverandThe Cult of the Leader: A Manifesto for More Authentic BusinessОценок пока нет

- Chap 8 1drДокумент51 страницаChap 8 1drbalutansutraОценок пока нет

- California Wine ClusterДокумент24 страницыCalifornia Wine ClusterNino Khatiashvili100% (1)

- Brand Valued: How socially valued brands hold the key to a sustainable future and business successОт EverandBrand Valued: How socially valued brands hold the key to a sustainable future and business successОценок пока нет

- Exploring A Michigan Hop CooperativeДокумент2 страницыExploring A Michigan Hop CooperativeJames CampbellОценок пока нет

- Robert Mondavi & Wine IndustryДокумент10 страницRobert Mondavi & Wine Industrypaco_burg100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0007681316300192 MainДокумент7 страниц1 s2.0 S0007681316300192 Main罗准恩 Loh Chun EnОценок пока нет

- Company Towns Concepto Historiografía Marcelo Borges Susana Torres Resumen PDFДокумент25 страницCompany Towns Concepto Historiografía Marcelo Borges Susana Torres Resumen PDFSalvemos Fábrica La TrinidadОценок пока нет

- Canadian Business' FamiliesДокумент28 страницCanadian Business' FamiliesBusiness Families FoundationОценок пока нет

- Done Deals: Venture Capitalists Tell Their StoriesДокумент438 страницDone Deals: Venture Capitalists Tell Their StoriespiscoОценок пока нет

- How Corporations Can Compete in a Changing EnvironmentДокумент20 страницHow Corporations Can Compete in a Changing EnvironmentaddreenaОценок пока нет

- CH 1 EntrepreneurshipДокумент19 страницCH 1 EntrepreneurshipGursahib Singh JauraОценок пока нет

- Nike Social ResponsibilityДокумент20 страницNike Social ResponsibilitySherlok HolmesОценок пока нет

- Start Up What We May Still Learn From Silicon Valley Lebret ShortДокумент24 страницыStart Up What We May Still Learn From Silicon Valley Lebret ShortHerve LebretОценок пока нет

- March April 2014 Edition Foreign AffairsДокумент238 страницMarch April 2014 Edition Foreign AffairszzankoОценок пока нет

- Silicon Valley's Success Brings ChallengesДокумент3 страницыSilicon Valley's Success Brings ChallengesIlham RamadhanОценок пока нет

- Opportunity in CrisisДокумент4 страницыOpportunity in CrisisSwapnil ShethОценок пока нет

- The Nature and Growth of EntrepreneurshipДокумент3 страницыThe Nature and Growth of EntrepreneurshipOronde ChaseОценок пока нет

- 08 069 Fair Trade Coffee The Mainstream Debate LockeДокумент23 страницы08 069 Fair Trade Coffee The Mainstream Debate LockeCoordom Comercio JustoОценок пока нет

- Disruptive Economy and Poverty of Knowledge Sri Lankans Have A Lot To LearnДокумент13 страницDisruptive Economy and Poverty of Knowledge Sri Lankans Have A Lot To LearnThavamОценок пока нет

- REI Booklet Print v1.2 2Документ27 страницREI Booklet Print v1.2 2Institute for Open Economic Networks (I-Open)Оценок пока нет

- GE6102 The Contemporary WorldДокумент19 страницGE6102 The Contemporary WorldEun HyeОценок пока нет

- GE6102 The Contemporary WorldДокумент9 страницGE6102 The Contemporary WorldEun HyeОценок пока нет

- America - HistoryДокумент4 страницыAmerica - HistoryRuth AsuncionОценок пока нет

- Development of Creative IndustryДокумент12 страницDevelopment of Creative IndustrygabrielamesnitaОценок пока нет

- VILLASIS (Assignment)Документ2 страницыVILLASIS (Assignment)MarvZz Villasis100% (10)

- Flipping OrthodoxiesДокумент6 страницFlipping OrthodoxiesSergiu RusuОценок пока нет

- WeTransfer On Companies and CommunitiesДокумент51 страницаWeTransfer On Companies and CommunitiescgoulartОценок пока нет

- Gilbert G. Lenssen, N. Craig Smith - Walmart 1Документ17 страницGilbert G. Lenssen, N. Craig Smith - Walmart 1Eduardo AndresОценок пока нет

- Activity 1: A Case StudyДокумент7 страницActivity 1: A Case StudyAllyssa Mae De LeonОценок пока нет

- Trade, Technology and International CompetitivenessДокумент232 страницыTrade, Technology and International CompetitivenessAndrés Felipe PeláezОценок пока нет

- Activity 1: A Case StudyДокумент7 страницActivity 1: A Case StudyAllyssa Mae De LeonОценок пока нет

- Vermont Dollars Vermont Sense (2015)Документ92 страницыVermont Dollars Vermont Sense (2015)Post Carbon Institute100% (1)

- Brand AmericaДокумент4 страницыBrand AmericadesigneducationОценок пока нет

- Fayerweather - The Internationalization of Business 1972Документ12 страницFayerweather - The Internationalization of Business 1972bejmanjin123Оценок пока нет

- Expert Business Analyst Darryl Cropper Seeks New OpportunityДокумент8 страницExpert Business Analyst Darryl Cropper Seeks New OpportunityRajan GuptaОценок пока нет

- CompactLogix 5480 Controller Sales GuideДокумент2 страницыCompactLogix 5480 Controller Sales GuideMora ArthaОценок пока нет

- Programme Report Light The SparkДокумент17 страницProgramme Report Light The SparkAbhishek Mishra100% (1)

- Variable Displacement Closed Circuit: Model 70160 Model 70360Документ56 страницVariable Displacement Closed Circuit: Model 70160 Model 70360michael bossa alisteОценок пока нет

- Complaint Handling Policy and ProceduresДокумент2 страницыComplaint Handling Policy and Proceduresjyoti singhОценок пока нет

- Photoshop Tools and Toolbar OverviewДокумент11 страницPhotoshop Tools and Toolbar OverviewMcheaven NojramОценок пока нет

- 3) Stages of Group Development - To StudsДокумент15 страниц3) Stages of Group Development - To StudsDhannesh SweetAngelОценок пока нет

- AKTA MERGER (FINAL) - MND 05 07 2020 FNLДокумент19 страницAKTA MERGER (FINAL) - MND 05 07 2020 FNLNicoleОценок пока нет

- Ralf Behrens: About The ArtistДокумент3 страницыRalf Behrens: About The ArtistStavros DemosthenousОценок пока нет

- PS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFДокумент55 страницPS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFLester LouisОценок пока нет

- EPS Lab ManualДокумент7 страницEPS Lab ManualJeremy Hensley100% (1)

- MATH2070 Computer Project: Organise Porject FoldДокумент4 страницыMATH2070 Computer Project: Organise Porject FoldAbdul Muqsait KenyeОценок пока нет

- Death Without A SuccessorДокумент2 страницыDeath Without A Successorilmanman16Оценок пока нет

- Elaspeed Cold Shrink Splices 2010Документ3 страницыElaspeed Cold Shrink Splices 2010moisesramosОценок пока нет

- 2022 Product Catalog WebДокумент100 страниц2022 Product Catalog WebEdinson Reyes ValderramaОценок пока нет

- ECON Value of The FirmДокумент4 страницыECON Value of The FirmDomsОценок пока нет

- Benchmarking Guide OracleДокумент53 страницыBenchmarking Guide OracleTsion YehualaОценок пока нет

- Trinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Документ13 страницTrinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCОценок пока нет

- Hardened Concrete - Methods of Test: Indian StandardДокумент16 страницHardened Concrete - Methods of Test: Indian StandardjitendraОценок пока нет

- ABBBAДокумент151 страницаABBBAJeremy MaraveОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1: The Investment Environment: Problem SetsДокумент5 страницChapter 1: The Investment Environment: Problem SetsGrant LiОценок пока нет

- Beams On Elastic Foundations TheoryДокумент15 страницBeams On Elastic Foundations TheoryCharl de Reuck100% (1)

- COVID-19's Impact on Business PresentationsДокумент2 страницыCOVID-19's Impact on Business PresentationsRetmo NandoОценок пока нет

- Module 5Документ10 страницModule 5kero keropiОценок пока нет

- Piping ForemanДокумент3 страницыPiping ForemanManoj MissileОценок пока нет

- Aci 207.1Документ38 страницAci 207.1safak kahraman100% (7)

- ATOMIC GAMING Technical Tutorial 1 - Drawing Game Statistics From Diversity Multigame StatisticsДокумент4 страницыATOMIC GAMING Technical Tutorial 1 - Drawing Game Statistics From Diversity Multigame StatisticsmiltoncgОценок пока нет

- ASME Y14.6-2001 (R2007), Screw Thread RepresentationДокумент27 страницASME Y14.6-2001 (R2007), Screw Thread RepresentationDerekОценок пока нет

- Planning For Network Deployment in Oracle Solaris 11.4: Part No: E60987Документ30 страницPlanning For Network Deployment in Oracle Solaris 11.4: Part No: E60987errr33Оценок пока нет

- Pig PDFДокумент74 страницыPig PDFNasron NasirОценок пока нет

- Summary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (22)

- How to Win Friends and Influence People: Updated For the Next Generation of LeadersОт EverandHow to Win Friends and Influence People: Updated For the Next Generation of LeadersРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (150)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverОт EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (186)

- An Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook's Battle for DominationОт EverandAn Ugly Truth: Inside Facebook's Battle for DominationРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (33)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeОт EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsОт EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (55)

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobОт EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (36)

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessОт EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (130)

- To Pixar and Beyond: My Unlikely Journey with Steve Jobs to Make Entertainment HistoryОт EverandTo Pixar and Beyond: My Unlikely Journey with Steve Jobs to Make Entertainment HistoryРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (26)

- Think Remarkable: 9 Paths to Transform Your Life and Make a DifferenceОт EverandThink Remarkable: 9 Paths to Transform Your Life and Make a DifferenceОценок пока нет

- The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesОт EverandThe War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our LivesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (8)

- Cultures of Growth: How the New Science of Mindset Can Transform Individuals, Teams, and OrganizationsОт EverandCultures of Growth: How the New Science of Mindset Can Transform Individuals, Teams, and OrganizationsОценок пока нет

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsОт EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (52)

- TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public SpeakingОт EverandTED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public SpeakingРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (209)

- Follow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipОт EverandFollow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (122)

- Brain Rules (Updated and Expanded): 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and SchoolОт EverandBrain Rules (Updated and Expanded): 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and SchoolРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (702)

- Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer AgeОт EverandDealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer AgeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (88)

- The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumОт EverandThe Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto-Hackers Is Building the Next Internet with EthereumРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (12)

- Overcoming Fake Talk: How to Hold REAL Conversations that Create Respect, Build Relationships, and Get ResultsОт EverandOvercoming Fake Talk: How to Hold REAL Conversations that Create Respect, Build Relationships, and Get ResultsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (3)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0От EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Оценок пока нет

- AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World OrderОт EverandAI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World OrderРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (398)

- Creating Competitive Advantage: How to be Strategically Ahead in Changing MarketsОт EverandCreating Competitive Advantage: How to be Strategically Ahead in Changing MarketsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- The 21 Indispensable Qualities of a Leader: Becoming the Person Others Will Want to FollowОт EverandThe 21 Indispensable Qualities of a Leader: Becoming the Person Others Will Want to FollowРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (38)