Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Fdi

Загружено:

Dinesh SharmaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Fdi

Загружено:

Dinesh SharmaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Dineshsharma 3092@gmail.

com

Battling huge vacancies, piling inventories and lacklustre rentals, the Indian real estate is looking forward to retail FDI as a savior, expecting a windfall following the entry of global giants looking for more retail space for expansion. As overseas chains line up to grab the biggest retail pie, experts see most developers dusting up shelved projects and trying out newer revenue and business models as they unexpectedly get to choose from a wider basket of brands. Facts speak for themselves. Close to 18.3 million square feet of retail space is expected to come in 2011, highest since 2005, and push up vacancies to 24% during the current fiscal from 18% in 2010, according to data by Jones Lang LaSalle India, a real estate research firm. Though absorption, too, would be higher at 12.1 million square feet, there would still be surplus space. Of this 12.1 msf, about 4.7 msf has already been absorbed in the first half. Pankaj Renjhen, Managing Director Retail Services, Jones Lang LaSalle India, says oversupply in many large cities present a huge opportunity for the foreign brands to take up space almost immediately. DLF, the countrys largest developer, was the first to latch on the opportunity by announcing Rs 3,000 crore investments in malls. In the next three to five years, the sector will grow and consumers will benefit. The supply chain issue will also be addressed by the industry adequately. We will invest Rs2,000 crore to Rs3,000 crore in the next five years, DLF Vice-Chairman Rajiv Singh says. Experts see more such announcements soon. Pranay Vakil, Chairman, Knight Frank India, says, Developers have been sitting on the fence waiting for this clearance. I surely see big developers coming up with retail projects. Out of 346 mall projects that are at various stages, about 15 were dropped in the past few years, most of them in Bangalore, according to Jones Lang LaSalle data. Most global research firms agree the country has long been on the radar for investment by foreign brands. Industry sources said Indian developers are likely to form joint ventures with foreign brands, which could entail a complete mall-management package from the developers side. FDI in retail is also seeing up opening a new segment in the retail space. Developers are expected to develop standalone structures and lease them out to long-format players like Wal-Mart that prefer to occupy an individual structure rather than setting up shop in malls. Also, developers would be spoilt for choice while picking up the brands.

DI in retail isnt going to be manna. It wont lead to deluge in FDI inflows. It wont stem rupee depreciation. It wont dampen food inflation. It wont lead to a revolution in retail trade and make it organised . But nor will be it be a bane that will drive kirana stores into oblivion. Outside TV studio debates, truth is never in black-and-white. As a shade of grey, the present decision is no more than the thin edge of liberalisation . All liberalisation is good for consumers. The colour of competition (national versus foreign) doesnt matter. There is choice, better quality and better service. There is downward pressure on prices. Post-1991 , this elementary proposition of economics has been empirically vindicated whenever competition has been allowed to seep in. There is no reason for consumers to be exploited by kirana stores, just as there is no reason for consumers to be exploited by the Future Group, Shoppers Stop or Vishal Retail. Having said this, there is also another elementary proposition . Perfect competition is a figment of imagination. It doesnt exist. The world is one of unfair and restrictive business practices. Hence, we need competition policy instruments . So far, thrust of competition policy intervention has been on manufacturing and some services. Retail trade hasnt figured prominently . While that focus has to change, this isnt an argument against opening up. Acrossthe-board opening up is infinitely preferable to selective and segmented opening up. Selective liberalisation distorts markets and allows opportunities for arbitrage. Take this business of opening up wholesale cash-andcarry . Who has this benefited? It hasnt helped consumers, at least not directly. It has helped hotels and so-called kirana stores, anyone who obtained a licence or got access to one. Why did we first allow 51% FDI in single-brand retail and why are we now opting for 100%? Who has benefited from this transition in policy between 2006 and 2011? There are foreign single-brand retailers who will now rework their joint ventures and jack up foreign equity to 100%. There are Indian joint venture partners who are cash-starved. The beneficiaries will thus be Indian joint-venture partners who will sell off 49% equity. Single-brand or multi-brand , wholesale (cash-and-carry ) or retail are artificial distinctions . We should simply have had 100% across-the-board . At some future date, Indian jointventure partners will benefit again when FDI multi-brand equity is jacked up to 100%. Other than this, geographical segmentation remains. Why should liberalisation be restricted to one-million-plus cities? Do consumers elsewhere not deserve choice? As it is, as public subsidies go, there are pronounced pro-urban biases. We will pamper them more through this new policy.

Real-estate costs being what they are, big-bang benefits for retail should actually be outside onemillion-plus cities. It gets worse if you read the Constitution . Delhi provides a framework policy. Implementation is up to states. While Seventh Schedule doesnt quite use the expression retail , production, supply and distribution of goods is Entry 27 in the State List. To the best of my understanding , this means a state may choose not to open up retail trade. It gets worse in

Sixth Schedule, since no person, who is not a member of the Scheduled Tribes resident in the district shall carry on wholesale or retail business in any commodity except under a licence issued in that behalf by the District Council . In general, deprived and backward states and regions are reluctant to open up. Thats the reason they arent mainstreamed and continue to remain deprived and backward. Stores will be in one-million-plus locations and consumers there will benefit. I have no problems with minimum threshold levels of foreign investment, or requirements that 50% has to be in back-end infrastructure. Retail today straddles assorted segments. Food is a small component, less than 10%. It doesnt have to be that way. However, reforming the agro economy involves much more than opening up FDI in retail. There are supply-side constraints . There is low productivity . There are infrastructure problems, storage and processing. There are controls on storage and distribution , APMC isnt the only one. If all that is reformed, with disintermediation, farmers should get higher prices, without consumers paying higher prices. Depending on the study and product it is higher for fruit and vegetables and lower for food grains disintermediation efficiencies are between 10% and 30%. But why should government have rights of purchase over farm produce and what does it mean? As it is, high procurement prices have driven out private grain trade. Finally, we are left with kirana stores, and this business of mandatory sourcing of 30% of purchases from MSMEs (or is it MSEs?) . No reforms are positive sum. There are gainers and losers. In this context, kirana stores will be losers. One shouldnt deny that. However, getting organised retail to work takes years and years. China is the obvious example, where organised retail penetration is still less than 10%. Kirana stores have resilience. They change their line of business. They adapt. One should have faith in that resilience. DI in retail isnt going to be manna. It wont lead to deluge in FDI inflows. It wont stem rupee depreciation. It wont dampen food inflation. It wont lead to a revolution in retail trade and make it organised . But nor will be it be a bane that will drive kirana stores into oblivion. Outside TV studio debates, truth is never in black-and-white.

As a shade of grey, the present decision is no more than the thin edge of liberalisation . All liberalisation is good for consumers. The colour of competition (national versus foreign) doesnt matter. There is choice, better quality and better service. There is downward pressure on prices. Post-1991 , this elementary proposition of economics has been empirically vindicated whenever competition has been allowed to seep in. There is no reason for consumers to be exploited by kirana stores, just as there is no reason for consumers to be exploited by the Future Group, Shoppers Stop or Vishal Retail. Having said this, there is also another elementary proposition . Perfect competition is a figment of imagination. It doesnt exist. The world is one of unfair and restrictive business practices. Hence, we need competition policy instruments . So far, thrust of competition policy intervention has been on manufacturing and some services. Retail trade hasnt figured prominently . While

that focus has to change, this isnt an argument against opening up. Acrossthe-board opening up is infinitely preferable to selective and segmented opening up. Selective liberalisation distorts markets and allows opportunities for arbitrage. Take this business of opening up wholesale cash-andcarry . Who has this benefited? It hasnt helped consumers, at least not directly. It has helped hotels and so-called kirana stores, anyone who obtained a licence or got access to one. Why did we first allow 51% FDI in single-brand retail and why are we now opting for 100%? Who has benefited from this transition in policy between 2006 and 2011? There are foreign single-brand retailers who will now rework their joint ventures and jack up foreign equity to 100%. There are Indian joint venture partners who are cash-starved. The beneficiaries will thus be Indian joint-venture partners who will sell off 49% equity. Single-brand or multi-brand , wholesale (cash-and-carry ) or retail are artificial distinctions . We should simply have had 100% across-the-board . At some future date, Indian jointventure partners will benefit again when FDI multi-brand equity is jacked up to 100%. Other than this, geographical segmentation remains. Why should liberalisation be restricted to one-million-plus cities? Do consumers elsewhere not deserve choice? As it is, as public subsidies go, there are pronounced pro-urban biases. We will pamper them more through this new policy. Real-estate costs being what they are, big-bang benefits for retail should actually be outside onemillion-plus cities. It gets worse if you read the Constitution . Delhi provides a framework policy. Implementation is up to states. While Seventh Schedule doesnt quite use the expression retail , production, supply and distribution of goods is Entry 27 in the State List. To the best of my understanding , this means a state may choose not to open up retail trade. It gets worse in Sixth Schedule, since no person, who is not a member of the Scheduled Tribes resident in the district shall carry on wholesale or retail business in any commodity except under a licence issued in that behalf by the District Council . In general, deprived and backward states and regions are reluctant to open up. Thats the reason they arent mainstreamed and continue to remain deprived and backward. Stores will be in one-million-plus locations and consumers there will benefit. I have no problems with minimum threshold levels of foreign investment, or requirements that 50% has to be in back-end infrastructure. Retail today straddles assorted segments. Food is a small component, less than 10%. It doesnt have to be that way. However, reforming the agro economy involves much more than opening up FDI in retail. There are supply-side constraints . There is low productivity . There are infrastructure problems, storage and processing. There are controls on storage and distribution , APMC isnt the only one. If all that is reformed, with disintermediation, farmers should get higher prices, without consumers paying higher prices. Depending on the study and product it is higher for fruit and vegetables and lower for food grains disintermediation efficiencies are between 10% and 30%. But why should government have rights of purchase over farm produce and what does it mean? As it is, high procurement prices have driven out private grain trade.

Finally, we are left with kirana stores, and this business of mandatory sourcing of 30% of purchases from MSMEs (or is it MSEs?) . No reforms are positive sum. There are gainers and losers. In this context, kirana stores will be losers. One shouldnt deny that. However, getting organised retail to work takes years and years. China is the obvious example, where organised retail penetration is still less than 10%. Kirana stores have resilience. They change their line of business. They adapt. One should have faith in that resilience.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- ETP48300-C6D2 Embedded Power User Manual PDFДокумент94 страницыETP48300-C6D2 Embedded Power User Manual PDFjose benedito f. pereira100% (1)

- CIS2103-202220-Group Project - FinalДокумент13 страницCIS2103-202220-Group Project - FinalMd. HedaitullahОценок пока нет

- Approvals Management Responsibilities and Setups in AME.BДокумент20 страницApprovals Management Responsibilities and Setups in AME.BAli LoganОценок пока нет

- Women Empowerment 1230306631611205 2Документ18 страницWomen Empowerment 1230306631611205 2Dinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- 02 - AbapДокумент139 страниц02 - Abapdina cordovaОценок пока нет

- Job Satisfaction Project ReportДокумент76 страницJob Satisfaction Project Reportkamdica92% (51)

- Finesse Service ManualДокумент34 страницыFinesse Service ManualLuis Sivira100% (1)

- Should Always: Exercise 1-1. True or FalseДокумент7 страницShould Always: Exercise 1-1. True or FalseDeanmark RondinaОценок пока нет

- E 0522935Документ7 страницE 0522935Dinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Presented By: Dinesh Sharma Manjunath Paramesh.K IliyasДокумент10 страницPresented By: Dinesh Sharma Manjunath Paramesh.K IliyasDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Womenentrepreneurship 120201065414 Phpapp02 131116041130 Phpapp02Документ27 страницWomenentrepreneurship 120201065414 Phpapp02 131116041130 Phpapp02Dinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

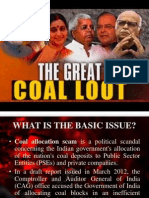

- Coal Mining ScamДокумент4 страницыCoal Mining ScamDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- ETHICS DEFINED: Normative, Descriptive and Metaethical ApproachesДокумент8 страницETHICS DEFINED: Normative, Descriptive and Metaethical ApproachesDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Business PlanДокумент26 страницBusiness PlanDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- MOTHER'S TOUCH Business PlanДокумент22 страницыMOTHER'S TOUCH Business PlanDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- MemorabaliaДокумент23 страницыMemorabaliaDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- FDI in IndiaДокумент16 страницFDI in IndiaDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- HospitalitysectorДокумент29 страницHospitalitysectorDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Tci Presentation q4 March 13Документ26 страницTci Presentation q4 March 13Dinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Presented By, Dinesh Sharma Reg. No. 121GCMA039 RvimДокумент17 страницPresented By, Dinesh Sharma Reg. No. 121GCMA039 RvimDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Coalgate 121123040002 Phpapp01Документ33 страницыCoalgate 121123040002 Phpapp01Dinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Company ProfileДокумент14 страницCompany ProfileDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Executive Summary: Industry ProfileДокумент85 страницExecutive Summary: Industry ProfileDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Projject Report On Bgs HospitalДокумент82 страницыProjject Report On Bgs HospitalDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Information Technology Act 2000 An Overview SethassociatespptДокумент86 страницInformation Technology Act 2000 An Overview SethassociatespptDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Project On KmsДокумент74 страницыProject On KmsDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Recruitment ProcessДокумент70 страницRecruitment ProcessDinesh SharmaОценок пока нет

- PTCL History, Services, Subsidiaries & SWOT AnalysisДокумент18 страницPTCL History, Services, Subsidiaries & SWOT AnalysiswaqarrnОценок пока нет

- Screenshot 2021-10-02 at 12.22.29 PMДокумент1 страницаScreenshot 2021-10-02 at 12.22.29 PMSimran SainiОценок пока нет

- Capital Asset Pricing ModelДокумент11 страницCapital Asset Pricing ModelrichaОценок пока нет

- Moi University: School of Business and EconomicsДокумент5 страницMoi University: School of Business and EconomicsMARION KERUBOОценок пока нет

- Supplement - 7 Procurement Manual: Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaДокумент8 страницSupplement - 7 Procurement Manual: Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDinuka MalinthaОценок пока нет

- Dragonshard PC GBДокумент42 страницыDragonshard PC GBWilliam ProveauxОценок пока нет

- Basic Concept of EntrepreneurshipДокумент12 страницBasic Concept of EntrepreneurshipMaria January B. FedericoОценок пока нет

- Culture GuideДокумент44 страницыCulture GuideLeonardo TamburusОценок пока нет

- Shilpa PPT FinalДокумент51 страницаShilpa PPT FinalDrakeОценок пока нет

- Gustilo Vs Gustilo IIIДокумент1 страницаGustilo Vs Gustilo IIIMoon BeamsОценок пока нет

- Educ 3 ReviewerДокумент21 страницаEduc 3 ReviewerMa.Lourdes CamporidondoОценок пока нет

- Panameterics GF 868 Flare Gas Meter PDFДокумент8 страницPanameterics GF 868 Flare Gas Meter PDFDaniel DamboОценок пока нет

- Basic Concept of Process Validation in Solid Dosage Form (Tablet) : A ReviewДокумент10 страницBasic Concept of Process Validation in Solid Dosage Form (Tablet) : A Reviewqc jawaОценок пока нет

- Demecio Flores-Martinez Petition For Review of Enforcement of Removal OrderДокумент9 страницDemecio Flores-Martinez Petition For Review of Enforcement of Removal OrderBreitbart NewsОценок пока нет

- Timesheet 2021Документ1 страницаTimesheet 20212ys2njx57vОценок пока нет

- Lessee Information StatementДокумент1 страницаLessee Information Statementmja.carilloОценок пока нет

- University of Texas at Arlington Fall 2011 Diagnostic Exam Text and Topic Reference Guide For Electrical Engineering DepartmentДокумент3 страницыUniversity of Texas at Arlington Fall 2011 Diagnostic Exam Text and Topic Reference Guide For Electrical Engineering Departmentnuzhat_mansurОценок пока нет

- Modicon Quantum - 140DDI85300Документ5 страницModicon Quantum - 140DDI85300Samdan NamhaisurenОценок пока нет

- DX DiagДокумент31 страницаDX DiagJose Trix CamposОценок пока нет

- Solved Problems: EEE 241 Computer ProgrammingДокумент11 страницSolved Problems: EEE 241 Computer ProgrammingŞemsettin karakuşОценок пока нет

- CV of Prof. D.C. PanigrahiДокумент21 страницаCV of Prof. D.C. PanigrahiAbhishek MauryaОценок пока нет

- Cache Memory in Computer Architecture - Gate VidyalayДокумент6 страницCache Memory in Computer Architecture - Gate VidyalayPAINОценок пока нет

- Aggregate Demand and Supply: A ReviewДокумент36 страницAggregate Demand and Supply: A ReviewYovan DharmawanОценок пока нет

- Environmental Pollution and Need To Preserve EnvironmentДокумент3 страницыEnvironmental Pollution and Need To Preserve EnvironmentLakshmi Devar100% (1)