Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Open Market Operations

Загружено:

Jayanta SaudИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Open Market Operations

Загружено:

Jayanta SaudАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Open market operations (also known as OMO) is the buying and selling of government bonds on the open market

by a central bank. It is the primary means of implementing monetary policy by a central bank. The usual aim of open market operations is to control the short term interest rate and the supply of base money in an economy, and thus indirectly the total money supply. This involves meeting the demand of base money at the target interest rate by buying and selling government securities, or other financial instruments. Monetary targets such as inflation, interest rates or exchange rates are used to guide this implementation.[1][2]

Contents

[hide]

1 Process 2 Possible targets of open market operations 3 How open market operations are conducted

3.1 USA 3.2 Eurozone 3.3 Switzerland

4 See also 5 References 6 External links

[edit]Process Since most money is now in the form of electronic records rather than cash, open market operations are conducted simply by electronically increasing or decreasing ('crediting' or 'debiting') the amount of base money that the bank has in its reserve account at the central bank. Thus, the process does not literally require new currency. (However, this will increase the central bank's requirement to print currency when the member bank demands banknotes, in exchange for a decrease in its electronic balance.) When there is an increased demand for base money, action is taken in order to maintain the short term interest rate (that is, to increase the supply of base money). The central bank goes to the open market to buy a financial asset such as government bonds, foreign currency, gold, or seemingly nonvolatile (until the 2008 financial fallout) MBS's [3] (Mortgage Backed Securities). To pay for these assets, bank reserves in the form of new base money (for example newly printed cash) is transferred to the sellers bank, or to seller if it is a bank, and the sellers account is credited. Thus, the total amount of base money in the economy has increased. Conversely, if the central bank sells these

assets in the open market, the amount of base money that the buyer's bank holds decreases, effectively destroying base money. [edit]Possible

targets of open market operations

Under inflation targeting, open market operations target a specific short term interest rate in the debt markets. This target is changed periodically to achieve and maintain an inflation rate within a target range. However, other variants of monetary policy also often target interest rates: the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank use variations on interest rate targets to guide open market operations.

Besides interest rate targeting there are other possible targets of open markets operations. A second possible target is the contraction of the money supply, as was the case in the U.S. in the late 1970s through the early 1980s under Fed Chairman Paul Volcker.

Under a currency board open market operations would be used to achieve and maintain a fixed exchange rate with relation to some foreign currency.

Under a gold standard, notes would be convertible to gold, so there would be no open market operations. However, open market operations could be used to keep the value of a fiat currency constant relative to gold.

A central bank can also use a mixture of policy settings that change depending on circumstances. A central bank may peg its exchange rate (like a currency board) with different levels or forms of commitment. The looser the exchange rate peg, the more latitude the central bank has to target other variables (such as interest rates). It may instead target a basket of foreign currencies rather than a single currency. In some instances it is empowered to use additional means other than open market operations, such as changes in reserve requirements or capital controls, to achieve monetary outcomes.

[edit]How [edit]USA

open market operations are conducted

Further information: Monetary policy of the USA In the United States, as of 2006 the Fed sets an interest rate target for the Fed funds (overnight bank reserves) market. When the actual Fed funds rate is higher than the target, the New York Reserve Bank will usually increase the money supply via a repo (effectively borrowing from the dealers' perspective; lending for the Reserve Bank). When the actual Fed funds rate is less than the target, the Bank will usually decrease the money supply via a reverse repo (effectively lending from the dealers' perspective; borrowing for the Reserve Bank). In the U.S., the Federal Reserve (Fed) most commonly uses overnight repurchase agreements (repos) to temporarily create money, or reverse repos to temporarily destroy money, which offset temporary changes in the level of bank reserves.[4] The Fed also makes outright

purchases and sales of securities through the System Open Market Account (SOMA) with its manager over the Trading Desk at the New York Reserve Bank. The trade of securities in the SOMA changes the balance of bank reserves, which also affects short term interest rates. The SOMA manager is responsible for trades that result in a short term interest rate near the target rate set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), or create money by the outright purchase of securities.[5] Very rarely will it permanently destroy money by the outright sale of securities.[citation needed] These trades are made with a group of about 22 (currently 18 as an immediate aftermath of 08/09 credit crisis) banks or bond dealers who are called primary dealers. Money is created or destroyed by changing the reserve account of the bank with the Fed. The Fed has conducted open market operations in this manner since the 1920s, through the Open Market Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee. The open market operation is also a means through which inflation can be controlled because when treasury bills are sold to commercial banks these banks can no longer give out loans to the public for the period and therefore money is being reduced from circulation. [edit]Eurozone The European Central Bank has similar mechanisms for their operations; it describes its methods as a four-tiered approach with different goals: beside its main goal of steering and smoothingEurozone interest rates while managing the liquidity situation in the market the ECB also has the aim of signalling the stance of monetary policy with its operations. Broadly speaking, the ECB controls liquidity in the banking system via Refinancing Operations, which are basically repurchase agreements,[6] i.e. banks put up acceptable collateral with the ECB and receive a cash loan in return. These are the following main categories of refinancing operations that can be employed depending on the desired outcome:

The regular weekly main refinancing operations (MRO) with maturity of one week and, the monthly longer-term refinancing operations (LTRO) provide liquidity to the financial sector, while ad-hoc

"fine-tuning operations" (in the form of reverse or outright transactions, foreign exchange swaps and the collection of fixed-term deposits) aim to smooth interest rates caused by liquidity fluctuations in the market and

"structural operations" are used to adjust the central banks' longer-term structural positions vis-avis the financial sector.

Refinancing operations are conducted via an auction mechanism. The ECB specifies the amount of liquidity it wishes to auction (called the allotted amount) and asks banks for expressions of interest. In a fixed rate tender the ECB also specifies the interest rate at which it is willing to lend money; alternatively, in a variable rate tender the interest rate is not specified and banks bid against each other (subject to a minimum bid rate specified by the ECB) to access the available liquidity.

MRO auctions are held on Mondays, with settlement (i.e. disbursal of the funds) occurring the following Wednesday. For example at its auction on 2008 October 6, the ECB made available 250 million in EUR on October 8 at a minimum rate of 4.25%. It received 271 million in bids, and the allotted amount (250) was awarded at an average weighted rate of 4.99%. Since mid-October of 2008 however, the ECB has been following a different procedure on a temporary basis, the fixed rate MRO with full allottment. In this case the ECB specifies the rate but not the amount of credit made available, and banks can request as much as they wish (subject as always to being able to provide sufficient collateral). This procedure was made necessary by the financial crisis of 2008 and is expected to end at some time in the future. [edit]Switzerland The Swiss National Bank currently targets the 3 month Swiss franc LIBOR rate. The primary way the SNB influences the 3 month Swiss franc LIBOR rate is through open market operations, with the most important monetary policy instrument being repo transactions.[7]

For the interest rate charged to banks for borrowing short-term funds directly from the Federal Reserve, see discount window. For the fees charged to merchants for accepting credit cards, see Discount Rate under Merchant Account. For discount rate as a term in investment financing, see Discounted cash flow

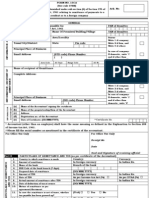

German central bank discount interest rates

The discount rate can mean

an interest rate a central bank charges depository institutions that borrow reserves from it, for example for the use of the Federal Reserve'sdiscount window.

the same as interest rate; the term "discount" does not refer to the common meaning of the word, but to the meaning in computations ofpresent value, e.g. net present value or discounted cash flow

the annual effective discount rate, which is the annual interest divided by the capital including that interest; this rate is lower than the interest rate; it corresponds to using the value after a year as the nominal value, and seeing the initial value as the nominal value minus adiscount; it is used for Treasury Bills and similar financial instruments

Contents

[hide]

1 Annual effective discount rate 2 Business calculations 3 See also 4 References 5 External links

[edit]Annual

effective discount rate

The annual effective discount rate is the annual interest divided by the capital including that interest, which is the interest rate divided by 100% plus the interest rate. It is the annual discount factor to be applied to the future cash flow, to find the discount, subtracted from a future value to find the value one year earlier. For example, suppose there is a government bond that sells for $95 and pays $100 in a year's time. The discount rate according to the given definition is

The interest rate is calculated using 95 as its base:

For every annual effective interest rate, there is a corresponding annual effective discount rate, given by the following formula:

or inversely,

where the approximations apply for small i and d; in fact i - d = id. See also notation of interest rates. [edit]Business

calculations

Businesses need to consider the discount rate when deciding whether to spend some of their profits on buying a new piece of equipment, or whether to give the profit back to their shareholders. In an ideal world, they would only buy a piece of equipment if the shareholders would get a bigger profit later. The amount of extra profit that a shareholder requires in the future in order to prefer that the company buy the equipment rather than giving them the profit now is based on the shareholder's discount rate. There is a widely used way of estimating shareholder's discount rates using share price data. It is known as the capital asset pricing model. Businesses normally apply this discount rate to their decisions about purchasing equipment by calculating the net present value of the decision

What is the meaning of Bills of Exchange?

Investor Words defines Bills of Exchange as an unconditional order issued by a person or business which directs the recipient to pay a fixed sum of money to a third party at a future date. The future date may be either fixed or negotiable. A bill of exchange must be in writing, signed and dated. It is also called a draft. The bills of exchange provide a method for the provision of credit, i.e. a loan. But it is more than that. The Bill is negotiable during its life and it can be passed by one person to another as a medium of exchange, effectively serving the purpose of money. Apart from this, at each stage that the Bill is passed on, the person who sells it guarantees the buyer against default on the loan. Thus, a bill of exchange is a kind of check or promissory note without interest and it is used primarily in international trade. If thebill of exchange is drawn on a bank, it is called a bank draft. If it is drawn on another party, it is called a trade draft. There are three parties involved in the bills of exchange - the drawer, the drawee and the beneficiary. A drawer is a person who makes or issues the bill of exchange and facilitates the drawee to pay the bill. A drawee is the person who promises to pay the money on a certain specific date.

In Britain, a bill of exchange is defined by the Bills of Exchange Act 1882 as an unconditional order in writing addressed by one person to another, signed by the person giving it, requiring the person to whom it is addressed to pay on demand or at a fixed or determinable future time a certain sum in money to or to the order of a specified person, or to the bearer. It is very much possible that you have the bills of exchange and for some or the other reason, your bills of exchange get bound, it is indeed a situation of great difficulty. Easylawyers - solicitors law firm, can help you out overcome this problem regardingcancelled cheque, returned cheque, stopped cheque, unpaid cheque clearance. Easylawyers charges 50% Bounced (dishonoured) cheque of 5,000 and below. Whereas, the fees for bounced (dishonoured) cheque of between 5,001 and above are negotiated under Conditional Fee Agreement. Hope you can get exact idea about Bills of Exchange.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Extrajudicial Settlement of Estate YlaganДокумент3 страницыExtrajudicial Settlement of Estate YlaganAustria Abiel80% (5)

- Parivarthan ModicareДокумент53 страницыParivarthan Modicareisometric_view78% (9)

- AmitДокумент16 страницAmitInderjeet RaiОценок пока нет

- Question SetДокумент3 страницыQuestion SetmyuploadsОценок пока нет

- Microfinance ProductsДокумент3 страницыMicrofinance Productsshyam patidarОценок пока нет

- Resume Sumanta NayakДокумент3 страницыResume Sumanta NayakPankaj KamraОценок пока нет

- Merchant BankeingДокумент2 страницыMerchant BankeingRajjan PrasadОценок пока нет

- Grafic Rate Credit NegociateДокумент6 страницGrafic Rate Credit NegociateCatalin PicОценок пока нет

- Khatabook Customer Transactions 08.04.2024 07.24.41.PMДокумент11 страницKhatabook Customer Transactions 08.04.2024 07.24.41.PMfaizancscmailОценок пока нет

- EPS Revolutionising TH Indian ATM Industry PDFДокумент48 страницEPS Revolutionising TH Indian ATM Industry PDFBkFromIndiaОценок пока нет

- Rick's Cabaret BMC 092711 FДокумент15 страницRick's Cabaret BMC 092711 FAndre TerrellОценок пока нет

- Money Laundering and Tax Evasion and Acceding CountriesДокумент23 страницыMoney Laundering and Tax Evasion and Acceding Countries11111Оценок пока нет

- MR Chetan Shankar Patil: Insurance AdvisorДокумент7 страницMR Chetan Shankar Patil: Insurance Advisordvs_5352_291349669Оценок пока нет

- SEO University Presentation 2012 (For Presenting) FINAL PDFДокумент42 страницыSEO University Presentation 2012 (For Presenting) FINAL PDFNaveen KarkiОценок пока нет

- Yes BankДокумент74 страницыYes BankRabia KhanОценок пока нет

- Role of SMEs in The Economy of BangladeshДокумент15 страницRole of SMEs in The Economy of BangladeshFarhad Reza67% (6)

- Valuation of Airthread Connections Questions TraductionДокумент2 страницыValuation of Airthread Connections Questions TraductionNatalia HernandezОценок пока нет

- Recharge Amount: Original Copy For Recipient - Tax InvoiceДокумент1 страницаRecharge Amount: Original Copy For Recipient - Tax InvoiceRoshan MahtoОценок пока нет

- Fabm1 q3 Mod9 TrialbalanceДокумент11 страницFabm1 q3 Mod9 TrialbalanceXedric JuantaОценок пока нет

- Effect of Monetary Policy On Real Sector of NepalДокумент6 страницEffect of Monetary Policy On Real Sector of Nepalmr_vishalxpОценок пока нет

- 15CAДокумент2 страницы15CAShant NagChaudhuriОценок пока нет

- Industrial Sickness-Causes & RemediesДокумент3 страницыIndustrial Sickness-Causes & RemediesdeepshrmОценок пока нет

- Project AssignmentsДокумент3 страницыProject AssignmentsMiruna IuliaОценок пока нет

- Rosales V CAДокумент3 страницыRosales V CADiane Dee YaneeОценок пока нет

- Final Location Survey and Other Preliminary Activities in Connection With 4th Line Between Mathura-Palwal Section (80kms)Документ63 страницыFinal Location Survey and Other Preliminary Activities in Connection With 4th Line Between Mathura-Palwal Section (80kms)sahoobdОценок пока нет

- Synopsis of Companies Act, 2013Документ10 страницSynopsis of Companies Act, 2013Ankit Srivastava0% (1)

- Pointers in AuditingДокумент3 страницыPointers in AuditingXandae MempinОценок пока нет

- Kunci TitmanДокумент98 страницKunci TitmanFadhil AlamsyahОценок пока нет

- BellonДокумент7 страницBellonValeria Rendon NoyolaОценок пока нет

- Frauds in Micro FinanceДокумент6 страницFrauds in Micro FinanceSyed MohammedОценок пока нет