Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Anthropology Note 1

Загружено:

একটি অণুИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Anthropology Note 1

Загружено:

একটি অণুАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

What is anthropology? What are the subjects matters of anthropology? Why it is important to study anthropology?

Anthropology Anthropology (from the Greek, anthropos, man) a term signifying that branch of science which has man for its subject. In its proper sense, it is very comprehensive, and of course includes anatomy, physiology, psychology, ethnology, history, theology, aesthetics, etc. The science of man, or natural history of mankind; in the general classification of knowledge, the highest section of zoology or the science of animals, which is itself the highest section of biology or the science of living beings. To anthropology contribute the sciences of anatomy, physiology, ethics, sociology, prehistoric archaeology; although each of these branches of investigation pursues its own subject, having no further contact with anthropology than when its research concerns man. It is the office of anthropology to collect and set forth, as completely as possible, the synopsis of mans physical and mental nature, and the theory of his course of life and action from his first appearance on the planet. Looking at mans place in nature, we see that the higher apes come nearest to him in bodily formation, and here it is the office of zoology to point out resemblances and differences, and to ascertain relations. At this point, says Professor Owen, in a paper on the bony structure of apes, every deviation from the human structure indicates with precision its real peculiarities, and we then possess the true means of appreciating those modifications by which a material organism is especially adapted to becoming the seat and instrument of a rational and responsible soul. Huxley, in comparing man with other orders of mammalians, decides There would remain then but one order for comparison that of the apes, and the question for discussion would narrow itself to this: Is man so different from any of these apes that he must form an order by himself? Or does he differ less from them than they differ from one another, and hence must he take his place in the same order with them? Here the reference plainly limits itself to the human body. The greater amount of brain in man comes nearer to explain the difference; but even that fails. In some of the senses man is quite inferior; he cannot equal the eagle in sight, the dog in scent, nor one of a dozen animals in hearing; though in the senses of tasting and feeling he may be superior to any of them. We must conclude that it is by superiority in quality, as well as in quantity, of brain, and, because of that superiority, by the possession of a highly organized language, that man has the power of co-ordination the impressions of his senses, which enables him to understand the world in which he lives, and, by understanding, to use,

resist, and rule it. That this power is a function of the brain has been fully proved in diseases of that organ, such as aphasia. This may stand among the best evidence that the brain is the principal, if not the sole, organ of mind. And anthropology study about that. Definition and Distinctive Characteristics of Anthropology Anthropology is the study of humankind. Of all the disciplines that examine aspects of human existence and accomplishments, only Anthropology explores the entire panorama of the human experience from human origins to contemporary forms of culture and social life. Anthropology is a generalizing and comparative discipline with a concern for understanding human diversity on a global scale. Anthropologists engage in empirical research with established theories, methods, and analytical techniques. They conduct field-based research as well as laboratory analyses and archival investigations. A hallmark of Anthropology is its holistic perspective understanding humankind in terms of the dynamic interrelationships of all aspects of human existence. Different aspects of culture and society exhibit patterned interrelationships (e.g., political economy, social configurations, religion and ideology). Culture cannot be divorced from biology and adaptation, nor language from culture. Contemporary societies cannot be understood without consideration of historical and evolutionary processes. Anthropological research is typically conducted via immersion within the community or context under study (including virtual communities and archaeological sites). The participant-observer method of research was developed early in the discipline of Anthropology and remains one of its cornerstones. Anthropology transcends such distinctions in research and applications as macro- and micro scale (e.g., global-local), the exotic and the familiar, the past and the present. Its distinct epistemology respects the disparities between our views of the other and their views of us.

Anthropologists typically engage in particularistic research that contributes to the big questions about the human condition: who we are as a species and a diversity of societies and cultures, how we came to be that way, and what our future prospects are. In recent decades Anthropology has become more selfreflexive and involved with communities and with social conflicts as anthropologists increasingly apply their findings to real world social issues and engage their subjects as colleagues and collaborators. Overall anthropology is a comparative science that examines human biological and cultural diversity. At its broadest, the study of who humans are and what we do. Anthropology as an Integrative Interdisciplinary Discipline: The Four Fields With its holistic perspective, Anthropology intersects the multiple approaches to the study of humankindbiological, social, cultural, historical, linguistic, cognitive, material, technological affective, and aesthetic. This interdisciplinary is integrated within Anthropology as a whole and formalized in the four major fields that compose the discipline archaeological, biological, linguistic, and socio cultural anthropologyalthough many anthropologists also conduct research across these fields. 1. Archaeological anthropologists are concerned with the evolution and historical changes to cultural and sociopolitical configurations, the materiality of human experience, and the stewardship and interpretation of cultural heritage. 2. Biological anthropologists are concerned with the physical and bicultural aspects of humans, including biological aspects of human health and well being; micro- and macro evolutionary study of the human condition; relationships to other primates; human growth and development; pathology, mortality and morbidity; and population genetics. 3. Linguistic anthropologists examine the history and structure of human languages, the relationship between

language and culture, cognitive and biological aspects of language, and other symbolic forms and media of communication and reasoning. 4. Socio cultural anthropologists are concerned with human social and cultural diversity and the bases of these distinctions, be they economic, political, environmental, biological; social roles, relationships, and social transformation; cultural identity; cultural dimensions of domination and resistance; and strategies for representing and analyzing cultural knowledge. Anthropology therefore transcends what are typically perceived as intellectual boundaries separating natural science, social science, and humanities. Anthropologists conduct research, and receive grants from funding agencies, in all three major areas. While it is the case that many Anthropology departments across the country are experiencing internal divisions and visioning, four-field trained anthropologists continue to be sought for employment, especially for academic positions. Education for the 21st Century: The Need for Anthropology Anthropology students benefit from the holistic approach that intersects natural science, social science, and humanistic perspectives on the human condition. The spatial field of anthropology is global, and the temporal scale extends millions of years into the past, examining evolutionary and historical changes alongside concerns for our shared future. Anthropology students become adept at understanding the cultural, biological, environmental, and historical bases for behaviors and precepts in their own and other societies. The self-reflection that results from applying the holistic approach and comparative method provides a broadened world view, one that rejects naive ethnocentrisms and is more open to acceptance of other ways of living. Students develop as global citizens, aware of the world around them

their similarities, differences, and inequalities with other peoples or groups. Anthropology students are trained in the full suite of liberal arts skillsoral and written communication, interpersonal skills, problem-solving, research, and critical thinking needed for success in a variety of careers. These skills provide flexibility in career mobility, forming a foundation for life-long learning as employment possibilities are continually transformed. Anthropology further provides specific training in all of the skills recently identified as critical to education in the 21st century: 2 1. Nowing more about the world: global literacy, sensitivity to other cultures 2. Hinking outside the box: creative and innovative skills, finding patterns in complex and chaotic configurations; being able to cross disciplinary boundaries 3. Beoming smarter about new sources of information: being able to process and critically evaluate increasingly rapid and changing information flows; understanding different forms of representation and avenues of communication 4. Developing good people skill: communication proficiency, especially across cultural and social difference; emotional intelligence; ability to work in teams. Anthropology undergraduate students have a variety of career options because of their broad reparation and focus on fundamental knowledges and skills. The bachelors degree is an entree to professional careers in law, medicine and public health, urban planning, educational administration, international relations and business, social work, and development. MA and PhD graduates are more likely to achieve positions as anthropologists, yet their career options are also quite open. Real World Anthropology Anthropologists conduct academic and applied research as a means to understand individual human lives within larger

socio-political contexts and to ameliorate human problems. Although traditionally archaeologists made their careers within academia, over half of new Anthropology PhDs in the US are employed in non-academic settings (government, non-governmental organizations, and business firms). Anthropologists engage many different publics, including those in the private sector. Anthropologists, both academic and applied, are engaging many contemporary issues that have global, national and community implications for policy-making and advocacy for individuals and groups. The following few examples illustrate the interconnectedness of these issues and the need for the holistic, interdisciplinary, macro-micro, and long-term perspectives of Anthropology to successfully tackle them: 1. Environmental Change: Ecological Sustainability, Global Warming, Water and Land Resources, Biodiversity, Anthropogenic Landscapes 2. Health and Nutrition: Infectious Disease (e.g., HIV/Aids), Health Care Policy, Resource Depletion and Famine, Bio-medicine, Alternative Medical Practices, Impediments (age, gender, race, class) to Health Care Access 3. Globalization: Global Economies, Sovereignty, Tran nationalism, Development, Diaspora, Migration and Citizenship, Preservation of Cultural Heritage 4. Social Justice and Human Rights: Democratization, StateSociety Relations, Community Organizing, Inter-Ethnic Relations, Racism, Sexism, Cultural Minorities, Indigenous Peoples 5. Cultural Dimensions of Civil and Religious Conflict: War, Militarism, Ethnocide, Religious Movements, Displaced Peoples

Although practitioners in other disciplines are also examining these same issues, anthropologists take into consideration how these topics and problems are embedded within material and institutional structures. Anthropologists consider the worldviews, practices, and the cultural, physical, and institutional constraints of the peoples affected. They seek workable empirically derived bottom up rather than top down solutions to local problems that can have global impacts.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

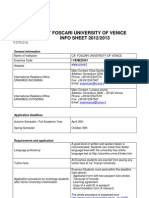

- Ca' Foscari University of Venice INFO SHEET 2012/2013: General InformationДокумент4 страницыCa' Foscari University of Venice INFO SHEET 2012/2013: General InformationCalum RiachОценок пока нет

- College Emcee ScriptДокумент10 страницCollege Emcee ScriptMa. April L. GuetaОценок пока нет

- Swapna SopДокумент4 страницыSwapna Sopapi-141009395Оценок пока нет

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4v90.002.10s Taught by Duane Buhrmester (Buhrmest)Документ3 страницыUT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4v90.002.10s Taught by Duane Buhrmester (Buhrmest)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupОценок пока нет

- Abdeen Mohamed Aslam: ObjectivesДокумент3 страницыAbdeen Mohamed Aslam: ObjectivesZitheeq UmarОценок пока нет

- Enroll GsДокумент6 страницEnroll GsGek CagatanОценок пока нет

- Subject: Applying For The Post of Programme Assistant at Euro Mediterranean Human Rights NetworkДокумент2 страницыSubject: Applying For The Post of Programme Assistant at Euro Mediterranean Human Rights NetworkSagyan Regmi RegmiОценок пока нет

- Mphil, PHD Aut-21Документ90 страницMphil, PHD Aut-21waqar Ahmed0% (1)

- University of TechnologyДокумент7 страницUniversity of Technologykev sevОценок пока нет

- Bulan Campus: Class ProgramДокумент43 страницыBulan Campus: Class ProgramSheryl BartolayОценок пока нет

- ESE 2015 Meit Order Final Result English F PDFДокумент13 страницESE 2015 Meit Order Final Result English F PDFAnonymous jJvtJmattBОценок пока нет

- Doon University, Dehradun: A State University of Uttarakhand GovernmentДокумент3 страницыDoon University, Dehradun: A State University of Uttarakhand GovernmentNidhi MehraОценок пока нет

- Wiley Online Library Journals List 20: Eal Sales Data SheetДокумент185 страницWiley Online Library Journals List 20: Eal Sales Data SheetOprean IrinaОценок пока нет

- CU-Boulder - CUBIC ProgramДокумент13 страницCU-Boulder - CUBIC ProgramHeather OwensОценок пока нет

- Dbatu - Academic - Calender-2021 - 22 Revised Ug and PG EngineeringДокумент3 страницыDbatu - Academic - Calender-2021 - 22 Revised Ug and PG EngineeringShubham JadhavОценок пока нет

- Juliette ForestДокумент1 страницаJuliette ForestWbush14Оценок пока нет

- Task 3: Essay EDUC113 Introduction To ICT For Teachers Jemma Cotgrave 32009625Документ5 страницTask 3: Essay EDUC113 Introduction To ICT For Teachers Jemma Cotgrave 32009625api-458249320Оценок пока нет

- Call LetterДокумент1 страницаCall LetterJoyshree GhoshОценок пока нет

- A Complete Guide To Study in ChinaДокумент34 страницыA Complete Guide To Study in ChinaRaafi ChОценок пока нет

- J Chamberlain CVДокумент7 страницJ Chamberlain CVapi-361249533Оценок пока нет

- Prospectus 2014 PDFДокумент214 страницProspectus 2014 PDFAnonymous dGIwc6mecОценок пока нет

- BrownДокумент7 страницBrownMaddyBaОценок пока нет

- Academic Stem StrandДокумент7 страницAcademic Stem StrandJhoe Anne B. LimОценок пока нет

- Truth and Pwer, Monks and Technocrats - WallaceДокумент22 страницыTruth and Pwer, Monks and Technocrats - WallaceAlejandro CheirifОценок пока нет

- Ugc Report VjtiДокумент98 страницUgc Report VjtiDIPAK VINAYAK SHIRBHATEОценок пока нет

- Selection List R 4 Web 01012020Документ701 страницаSelection List R 4 Web 01012020Only Entertainment100% (1)

- Du Iba Bba Brochure 2012-2013Документ26 страницDu Iba Bba Brochure 2012-2013William Grant0% (1)

- Accenture Registration PendingДокумент17 страницAccenture Registration PendingDru ReОценок пока нет

- Ed 197Документ4 страницыEd 197Nelyn Joy Castillon - EscalanteОценок пока нет