Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Bandits, Rebels or Criminals - African History and Western Criminology (Review Article)

Загружено:

Kudus AdebayoИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Bandits, Rebels or Criminals - African History and Western Criminology (Review Article)

Загружено:

Kudus AdebayoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

International African Institute

Bandits, Rebels or Criminals: African History and Western Criminology (Review Article) Author(s): Stanley Cohen Reviewed work(s): Source: Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 56, No. 4, Crime and Colonialism in Africa (1986), pp. 468-483 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1160001 . Accessed: 25/01/2012 05:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and International African Institute are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Africa: Journal of the International African Institute.

http://www.jstor.org

Africa, 56 (4), 1986

BANDITS, REBELS OR CRIMINALS: AFRICAN HISTORY AND WESTERN CRIMINOLOGY (REVIEW ARTICLE)

Stanley Cohen

It has long been a cliche in the social sciences to talk about the insulation of disciplines and sub-disciplines from each other. We all know what it is like to study a phenomenon - poverty, crime, the family - from within one academic paradigm and then come across a quite different view of the 'same' phenomenon. The result is usually self-pity: 'If only I had known what they were up to' or 'If only they knew what I was up to'. For Africanists - or any other field where subject matter rather than disciplinary boundaries provides some collective identity (conferences, journals, teaching) this, I assume, is less of a problem. A subject such as crime in colonial Africa would naturally attract sociologists, anthropologists and historians who would have little excuse for not knowing what each other meant by, say, 'colonialism'. For those of us in the strange business of criminology, however, the problem of insulation has been endemic, chronic and the subject of much rumination. Ever since its emergence as a separate body of knowledge and power at the end of the nineteenth century criminology has claimed a monopoly over its selfconstituted subject matter and also an 'interdisciplinary' character which embraces unto itself sociology, psychology, criminal law, psychiatry and much else. The faith of positivist criminology was that there was a 'thing' out there crime - whose existence and pathological nature were self-evident. The causes of this phenomenon were then to be uncovered through the paradigm of the natural sciences and its pathology ameliorated through a combination of technology and benevolence. The mid-1960s onslaught on conventional criminology from interactionist sociology of deviance, labelling theory and then various new, radical, critical or Marxist criminologies - was to challenge this positivist faith and also to open up the subject to the mainland of the social sciences. The results' have been exciting, confusing and - like most such intellectual movements - extremely uneven. At its centres of power the old criminology remains unchanged. And while the new criminology imported all sorts of ideas from the mainland, its own productions remain unknown to other social scientists. All this leads me to the purpose of this review: to see how two recent books about crime in Africa - Donald Crummey (ed.), Banditry, Rebellion and Social Protest in Africa, and Yves Brillon, Crime, Justice and Culture in Black Africa2 - might look from the perspective of recent criminology. The books could hardly be more different. Donald Crummey's quite excellent collection consists of seventeen papers by historians all sympathetic to popular/radical/history-frombelow; all are interested in criminality only in its relationship to resistance, rebellion and protest and all are inspired one way or the other by Hobsbawm's classic characterisation of the social bandit. Yves Brillon's study of crime and justice in Africa comes from a Western (French-Canadian) criminologist not particularly influenced by the new criminology nor much interested in the political significance of crime, but using the insights of anthropology to free himself from ethnocentrism.

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

469

Let me first give a highly condensed account of those hidden developments in criminologywhich should be of interestto Crummeyand his fellow historians.

POLITICSIN THE NEW CRIMINOLOGY

The dominant thrust of the new criminologies was to reverse the positivist separationof crime from the state, that is, to introducepolitics into criminology. The dual victory of the bourgeois state and of criminology itself had been to constitute the criminalquestion as belonging to a realmof knowledgeand power not partof the normalpoliticalprocessof democracy.By the end of the nineteenth century this victory was complete: welfare, justice, punishment, treatmentand criminology were not 'politics'.3 The crime/stateseparationwas challengedfrom two directionsrelevantto this review.The first was theoretically'cleaner'and relativelyunproblematic: insist to (in conventionalDurkheimian terms)on the relativenatureof crimeand deviance; to rejecttherefore,any reification crimeas the productof a universalaetiological of sequence;to directattentionawayfrombehaviourand towardsdefinition,reaction and social control. At the micro level this meant accountingfor the construction, application and effects of deviant and stigmatic labels. At the macro level this meant explainingthe origins of laws and punishments- convertingcriminology, in effect, into the sociologyof law. For Marxiststhe projectwas to createa political economy of law and punishment. For Foucault - an overwhelminginfluence in recent years - the problem was to locate the whole discourse of crime in terms of the birth of the state and of the 'human sciences' themselves. These interests find little equivalent attention among Crummey'shistorians: their object is behaviour, not definition. More obviously relevant is the second of the new criminology's political directions:not only explaining the (obvious) politics of law, but tryingto decodethe politicalmeaningsof criminalactionitself. The point here was to repudiatethe dominant positivist image of criminals as determined, beings, drivento actionby forcesbeyondtheir control. pathological An alternativeimage was proposed:criminalityas more meaningful,rationaland intentional. At the extreme - and here is where the theoreticaltroubles start the criminal emerges as a crypto-politicalactor, crime becomes an embryonic form of social protest. This replacementof images was part of a wider 'deviant (Pearson,1975):the 1960s' culturalrevolutionsagainstconventional imagination' cognitive boundaries and moral authorities. Vandals, soccer hooligans, sex offenders, drug takers, even schizophrenicsall became candidates(unwittingly in most cases) for attributionof meaning and political significance. Romantic, sentimental and misguided as this enterprise might now sound ('Homage to Catatonia',as it was dismissedby a latercritic)it allowedimportantcomparisons and insights. And it opened up the field to outside influences. One such influence was the new social history. It was at this point that E. P. Thompson, Hobsbawm and Rude were 'discovered' and adopted (no doubt without their blessing) by the new criminology. For surely the enterprise of rescuingtoday'sdeviantsfromthe wastebinof socialpathologywas exactlyparallel to these historians'attempts to rescue machine breakers,food rioters, poachers and smugglers from - in E. P. Thompson's ringing phrase - 'the enormous condescension of posterity'. For criminologists the lesson from this revitalised social history was that crime was central to understandingthe historical trans-

470

BANDITS, REBELS OR CRIMINALS

formationto capitalism. The message from Thompson on the Black Act, from Fatal Tree and,of course,fromHobsbawm's CaptainSwing,fromAlbion's primitive rebels and social bandits seemed clear enough: to listen to experiencein its own terms, from below, is to find its hidden significance. The criminologist'squestion becomes 'How would "our"hooligansappearif they were affordedthe same possibilitiesof rationalityand intelligibility say as those of EdwardThompson?' (Pearson, 1978: 134). This is not the place to look at the criticismswithin and againstradicalsocial historynor the fate of their equivalentsin the new criminology.4Enough to note the two historicalborrowingswhich criminologists fitted into their own emerging concerns.The first was to understandthe problemof definition(criminalisation) in terms of the emerging requirements of capitalist political economy - for of example, the transformation customaryrights into crime. The second was to restore(or attribute) politicalmeaningto crime.A numberof relatedideasbecome common here: boundary-blurring erosion of the boundariesbetween crime (the and politics and the disciplines used to comprehend them - Horowitz and Liebowitz, 1968);convergence similarityin behaviourand social labelling of (the certain forms of crime and marginalpolitics - Cohen, 1973); the politicisation of deviance the 'stigma contests' through which certain deviant groups seek to define themselves in political terms - Schur, 1980); and, most explicitly from social historians like Hobsbawm, equivalence (however different from political it seems - and however crude, primitive, inarticulateor even hopeless activity - crime under certainconditions serves equivalentfunctions to such recognised political forms as protest and resistance). This takes us to Crummey's volume.

AFRICAN HISTORY

For the criminologist sensitised to the political importanceof crime, Banditry, Rebellion SocialProtestin Africawill be an invaluable and source.A certainamount of decoding,though, is required.With the exceptionof the editor'scomprehensive review of the literatureand Ralph Austen's sceptical account of the relevance of Western models of resistance and heroic criminality to Africa, few of these historiansareexplicitlyconcernedwith the theoretical connectionsbetweencrime, law and the state which have so preoccupiedthe new criminology. They devote a few paragraphsto Hobsbawm and perhaps some other literature on social banditry and then - correctly - get down to the business of their history. These excellentpieces of work,then, each demandattentionin their own terms, and I am sure that I am doing some damage to their authors' intentions by extractingonly those themes of criminologicalinterest.This also means ignoring altogetherthose chapterswhere the startingpoint is not 'crime'preciselybecause these arehistoriesof clearlyidentifiedand uncontestedformsof protest,resistance and rebellion (for example, the black women's struggle againstthe OrangeFree State Pass Laws in 1913, the 1912 rebellion in Rwanda,the 1894 revolt against Italian overrule in Eritrea, or the famous Bambatharebellion). Of course, it is just the continuity (similarity?equivalence? convergence?) Africawhich colonialand post-colonial betweencrimeand politics in pre-colonial, assume.'The greatbeast'- the title of Crummey's the editorand his contributors introduction - is the uncontrolled, outraged reaction of the people: popular

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

471

violence which can only be understood 'in the light of other kinds of popular protest and politics' (p. 1). The task is to make this light clear, to rescue the beast from the 'classprejudice'which would dismiss it as disorder,anarchy,mere crime. As the editor sets them out, every element in this rescue operationby African historiansis parallelednot only in the revisionisthistoryof earlymodernEurope, but also the first phaseof revisionistcriminology:a sympathywith the underclass who sufferand resistdomination; identification that otherbeast,the leviathan an of of the modern state which claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence and then turns it against the people; the claimed relationshipbetween primary accumulation and property law, theft as 'the most primitive form of protest' (Engels). I will view these themes in the case studies of crime and social banditry and then raise some more general and methodological issues. The 'social'criminal 'Banditry','resistance','protest'and 'rebellion'are all termswhich can be defined by social science and in terms of behaviouralone (or its attendantconsciousness or subsequentconsequences).'Crime',on the other hand, is one of many possible definitions (others include 'conflict', 'dispute', 'trouble', 'deviance')which can be attachedto certain behavioursor events - but only by a legitimate authority (usually, the state). 'Crime' is infraction and not just action. Contraryto his own analysis and those of his contributors, Crummey oversimplifiesthe problemthen by statingthat 'Crimeis inherentlya formof protest, since it violates the law' (p. 3). As it stands this assertion makes no sense - in Africaor anywhereelse. There aremanyformsof crime- that is, actionsclassified as such by the state - which are not 'inherently forms of protest'. Violation of law cannot in itselfbe taken as an indicatorof protest. Crummeyis awareof this when he notes that crime may be accompaniedby many forms of consciousness and that 'class-basedlaws' engender a particularform of defiance. These two qualities- the politicalbase of the law and the type of consciousness which might accompany its infraction - are among the many we look for in claimingto connectcrimewith politics.These claimsmaybe strongand ambitious or weak and modest. Thus consider the differencesbetween these possibilities: all crime is inherently political; some crimes are political in the sense that they are informed by a particularconsciousness (such as class domination or sexual repression);crime is a primitive precursorof more sophisticatedpolitical forms (progression); crime sometimes serves the same social functions as politics crime can take on a politicalshape (politicisation); - the weakest or (equivalence); claim - crime is better understood if we place it in a political context. Each of these claims has quite different implications and imposes different standardsof proof. Without being made explicit, examples and permutationsof all of them may be found throughout Crummey's collection. Thus LarryYarak'scareful account of some twenty cases of murderand theft in the Gold Coast town of Elmina in the early nineteenth century makes only quite modest claims about the political significance of crime. His use of the criminal records(which are remarkably detailed, by the way, comparedto their modernequivalents)results in a nuancedpicture of the social divisions and class structure underthe Dutch regime.As the editorcomments,however,'Theft allows

472

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

valuable inferences about inequality in Elmina, but tells little about resistance' (p. 4). And the murdercases - which show so well the tensions and resentments between the various strata(masterand slave, traderand Dutch official) - only allowYarakto find 'an unmistakable socialdimension'(p. 33). Given the structure of the hearings before the Dutch Council, we have to be very careful about attributingmotivation:the historiancannot easily distinguish'social crime' from 'crime without qualification'. Now unless 'social' is to be given the particular meaning associated with Hobsbawm's distinction - the social bandit versus the ordinary bandit, a distinction in which 'social' really meanspolitical- it is not remarkable find to evidence for 'social crime'. All crime is social. This is not to detract from the valueof this sortof analysisbut to note thatconceptssuch as protestand resistance imply more than 'social'. A series of far more radicalclaims about the political natureof crime is found in William Freund's history of theft among the Birom tin miners of northern Nigeria. For the new criminology this is a most suggestive chapter, containing as it does variationsof all the main claims about relationshipbetween property crime and political resistance. These claims fall into two main groups. First, there is the notion that much theft arose from the Birom rejection of the capitalistnotion of property.Even if the 'persistentcommunityappropriation of tin ore' failed to achieve the ideological coherence of so much European resistanceto the capitalistinfringementof propertyrights, still it '. .. contained the germof a populist"moraleconomy"that conflictedwith the politicaleconomy of the mining companies and the state' (p. 50). The second set of claims deals with the actualhistoricalrelationships betweenperiodsof tin theft and heightened The possibilitieshere seem endless:theft politicalconsciousnessand organisation. from a primitive is the equivalent militancyand appearsbefore it (a progression of to a more sophisticatedform);theft occurs at some periods insteadof militancy; theft 'grew alongside' militancy (that is, of the Birom Political Union and the unions in the late 1940s and 1950s). Strikesin one periodapparentlyencouraged theft to expand, then at anotherperiod a decline in militancy was coupled with an extension of illicit activity. Freund is awarethat the range of these relationships(and the different ways they can be interpreted)must cast doubt on Engels's famous claim that crime was 'the earliest, crudest and least fruitful' form of rebellion. As he notes: 'The relationshipof theft to social protest, when placed in the general context of the resistanceof labour to the prerogativesof capital, is thus rathermore complex than the pure progression which Engels once proposed' (p. 59). Yes, though Freund sometimes covers over these complexities by implying that, in the long historical period he covers, tin theft continued to have the same meaning, continuedto evince the same clash betweenpopulist and statistmoraleconomies. He quotes in a footnote Peter Linebaugh'ssuggestionthat 'directappropriation' is a more accurateand less pejorativeword than 'theft' but dismisses this usage as too cumbersome. This is not, however, a matter of terminology, nor is the historical continuity implied by this contemporaryreport self-evident:

villagers do not and never have seen tin theft as a violation of any moral code which makes sense to them. Obtaining tin by theft is merely a modest recompensation for the expropriation of land and difficulties faced by Birom farmers; it expresses the belief that wealth has been appropriated unjustly by outsiders. [p. 57]

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

473

The fact that villagersdisliked even applying the word 'stealing' to what they were doing says little about the quality of this act as a form of 'social protest'. White-collarcriminals, corporateexecutives and governmentofficials - like the who Nigerianentrepreneurs stole in the Nationalisteraas a way to sharein mineral profits- also do not like being calledthieves. We cannottakethe offender'sdenial of criminality in itself as an indicator of other social meanings (such as 'expropriation','redistribution','recompensation','liberation' or 'protest'). Similar issues are raised by 'Fire on the mountain', David Prochaska's fascinatingaccountof Algerianreactionsto French colonialismat the end of the nineteenth century. This chapterwill be of particularinterest to criminologists because it is the only one which explicitly deals with definition and control as well as behaviour itself. By the same token it is the best illustration of the Thompson-Hay model: the criminalisation of customary activity and the resistance implied by subsequent violation of the law. As if in evidence of the blurred boundary between crime and politics, the editor includes this chapter in the 'Protest and Resistance' ratherthan the 'Criminality'section, though its 'crime' - setting forests alight - could be (and was) just as easily called 'arson' as the 'expropriations'of Freund's Nigerian miners could be called 'theft'. of The historicalbase of criminalisation the massiveexpropriation Algerian was lands (especially forests for cork oaks), their transferto French legal ownership and the application of a legal code with its own agencies of enforcement. One object of the sanction - and the new political economy it protected- was kcar: the controlled burning of forests which had been a fact of life for centuries of forest dwellers. Kcar was rational- part of a four-yearecological cycle in which the lower limbs of trees and underbrushwere burnt to open up clearingsin the forest - and traditional- part of complex cosmology which defined the nature of communal land. How did the Algerians respond to the combined assault on their traditional political economy by land expropriationand the applicationof the forest code? Besides writing petitions and other forms of conventional protest, they burnt the forests down: dramatic, 'monster' forest fires followed each set of expropriations.But no single explanationworks for all these forest fires - and Prochaskahas to move cautiouslythroughthe varyingaccountsprofferedby the threepartiesto the conflict.First, therewere the Algeriansthemselveswho yielded when they had to, put up with things, used subterfugeor startedfires either as consciousfornisof protestand revengeor as a continuationof the normalpractice of kcar (which sometimes led to uncontrolled fires). Second, there were those of the settlers and business interests who expressedno doubt about the political meaning of the action: the arsonistswere bandits, their torch the equivalent of the 'assassin'sambush'or the 'rebel's gun'. The threatof resistancepoweredby religious fanaticism created a powerful myth of Algerian banditry. Third, the government shared the same concerns but also understoodthat the majorityof fires originated from kcar rather than intentional sabotage. It is not a questionof weighing up one explanationagainstthe other;they form a single matrix. The French attempt to suppress kcar and its political economy (by legal codes and severe collective punishmentssuch as fines and confiscation) led the Algerians(or some of them)to respondin ways that could be called'arson', 'revenge', 'banditry', 'protest' - or 'continuation of traditional practice'. As Prochaskaexplains it, the French said: 'You can live in the forest as long as you

474

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

don't set fire to it'; the Algerians said: 'How can we live in the forest without setting fire to it?' We can begin our model at the point at which the traditionalbecomes defined as rule-breaking and criminalised,and then becomes (and/oris perceived to be) protest.Or we can begin with the criminalcategory (arson)which is 'really'protest but which is criminalised. Eitherway we havewhat sociologistsof deviancewould call 'deviancyamplification'or a 'controlcircuit'. That is: a spiral of control -deviance -- furthercontrol -* further deviance ... and so on, each stage with its characteristic myths and hostility. Or in Prochaska'smore familiarlanguage: a war of attrition. I will come back later to the complex interactionbeween the attributionof politicality by self and other. What is always at issue in the politics of deviance is the eventual definition of reality which the powerful succeed in imposing. A nice illustrationof the massivegap which can exist between the originalmeaning of action and the definition which the powerful prefer emerges from Allan Roberts'schapteron some 'terrorists'of the late nineteenth century:the Tabwa lion-men. His analysisdoes not raisethe same issues as Freund'sor Prochaska's because this was not a developed colonial political economy. (The editor rather obscurely refers to ' . . . a clear case of incipient criminality in the context of an incipientstate'.)The cleargap was betweenwhatRobertscallsthe missionaries' 'sublimely obtuse interpretation'(that is, their total refusal to accept that the killers were theriomorphicmen) and the range of possible explanationsof the killings. Even if this was not social banditry,the crimes had some heroic status and certainlyshouldbe understoodin their social contexts(local powerstruggles, the effect of famine, the advent of the Europeans):'the theriomorphicstrategy was availablefor use by a varietyof actorsin manydifferentcircumstances among which might be resistance to European colonizers' (p. 80). In searchof the social bandit If 'crime is inherently a form of protest' and banditry is 'simply a form of societies',then banditryis a formof protest.Once criminalitycommonto agrarian again, though, the editor'ssyllogism is contradicted both by his own comments and by the six chapters which deal with social banditry. There can be no doubt about the stimulus producedby Hobsbawm'soriginal distinction:between ordinarycriminalbanditsand social banditswho rise above predatorycrime and directtheir activitiesto redressthe wrongsof peasantsupon whom they depend for protection and support and who in turn idolise them as avengers, redistributorsand protectors. Despite the rich literature elsewhere, however, 'Africanistshave done little with bandits',notes Crummey.His volume fills this gap, though what is striking at first sight is an immediate scepticism about whether the category of social bandit is of any use at all to Africanists. In his own chapteraboutnineteenth-century EthiopianbanditryCrummeymakes a comment about the myth of the bandit Kassa which might be more general: 'We hear overtones of social banditry, but only by standing far back. As we approach they vanish' (p. 140). I sense, however, that the editor and at least most of his contributorswould still like to retain these overtones - despite their own negative evidence, which points only to unredeemed,ordinarybandits- as much as criminologistswould like 'their'criminalsto show some socialconsciousness.Only Austen is explicitly

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

475

pessimisticaboutthe whole enterpriseof'importing' Hobsbawminto Africa,and he states flatly that the concept of social bandit just does not apply. He offers, though, a typologyof heroiccriminalityin Africawhich gives crimea very explicit set of political meanings and which vindicates, he claims, Hobsbawm's project of seeing criminal deviance as the expression - in however archaica sense - of positive alternativesto dominant social values. The typology is based on the relationship between 'social crime' and the evolution of the state,'. . . beginning with a ruralsituation in which segmentary to self-helpprovidesan alternative official authorityand concludingwith the selfconscious use of criminalaction to overthrowmoderngovernments'(p. 90). The five resultanttypes are:the self-helpingfrontiersman; populist redistributor; the the professional the and underworld; picaro-trickster; the urbanguerrilla.Populist redistributionis, of course, closest to social banditrybut, accordingto Austen, is not found in African reality or folklore, and anyway is more a means of influencing the modernstate than opposing it with archaicpeasantvalues. This distinction seems to me less important than its undoubted political character. In a curious way - because he goes beyond the vague notion of 'social crime' and insists that crime expresses values which are alternativesto the dominant social order- Austen actually comes closer to expanding ratherthan restricting Hobsbawm's original project. Thus even professionalcriminals 'in both their actions and legends ... representa form of opposition to establishedorderwith its own socialmeaning'(p. 94). This mightbe true in the sense that such criminals challenge the capacity of the state to maintain its official version of the social order. It is surely not true, however, in terms of values or intentions. This type is much closer to the 'innovativecapitalists'who arecriminology'smain subjects: more 'meanly parasitical'than 'heroically radical' in Austen's terms. Austen makestwo furthergeneralpoints which aresurelyapplicableto all these histories. The first is that the social milieu of criminalevents cannot be assumed to be the same as the heroic legends which grow around them. The second is that more explicit attentionmust be given to the natureof the state. Hobsbawm, after all, identified the modern state as a minimum condition for social banditry - a stratificationsystem which transcendssegmented tribal or kinship groups. The vocabularyof deviance in Africa, Austen argues, is (was?)seldom state vs criminal or legitimate vs illegitimate acquisition of property. The substantivechapterson banditry,then, turn out to be less significant for any signs of socialbanditry- even its 'overtones'are absent- than for illustrating the opaque relationshipbetween forms of crime and phases in the development Gold Coast shows how of the state. Thus Ray Kea on pre-nineteenth-century mercantilismcreatedthe conditions for widespreadbanditryand brigandageas far back as the seventeenth century - before the arrival of colonial rule and capitalist relations of production. (A reading of current Western historical criminology sometimes gives the impression that theft is purely an artefactof capitalist political economy.) The two chapterson Ethiopia - Crummeyon the nineteenthcentury and Tim Fernyhough on the twentieth - find a somewhat different (and ironic) political significance in banditry.In a feudal-typesociety not colonised and with limited capitalist penetration, banditry became an institution dominated by the ruling class. It was a form of political competition, used to gain status, office and power (Ethiopia'sfirsttwo modernmonarchsboth cameto the thronethroughsheftenat).

476

BANDITS, REBELS OR CRIMINALS

These lives of plunder, outlawry and armed defiance show few links of a progressive or socially redeeming nature with the peasants who, next to the merchants,were the main victims of bandits.By providingan alternativeavenue to mobility, banditrydiffusedclass conflict. And eventuallythe sheftenat a term which conveys both a criminaland a political meaning('venalhighwayman'and 'prominent nobleman') - eventually lost its connection with the nobility and became wholly criminalised. If the Ethiopianbandits became nobles ratherthan rebels, then the Bushmen had a strangerfate. In Robert Gordon's terrible history the Bushmen - whose very name, he argues, originallymeant 'bandit' - pass from exploitationby the Cape settlers, then the German administration,to their eventual taming and 'praetorianisation': employmentby the occupyingSouth Africanarmyas trackers in pursuit of SWAPO guerrillas. Not social bandits, not noblemen, but mercenariesstudied by the army ethnologists from the Afrikaansuniversities. Any theory of the political significance of crime - whether in criminology or history - has to solve the vexed problem of the correspondence between consciousness and legitimation. That is, the relationshipbetween, on the one hand, the language, subjective meaning and motivation through which people comprehend(or describe)their own action, and, on the other, the credibilityand acceptabilityawardedto these accounts by significant others, in particularthe state and its accreditedagents of control. Very crudely, there are four logical possibilities:(i) the 'pure-political'deviant whose own account (e.g. in terms of deviant who neither 'rebellion') is accordedlegitimacy;(ii) the 'pure-ordinary' offers nor is assignedany type of political motive; (iii) the 'unknowing-political' deviant who does not show any apparent political consciousness, but who is awarded this by others (e.g. the juvenile delinquent recruited by radical deviantwhose criminologistsinto the class war);and (iv) the 'contested-political' own political account is not honouredby others (e.g. the dissenterin the Soviet Union labelled as schizophrenic). This typology is obviously very crude because of the different meanings of legitimacy here (agreement?credibility?comprehension?)and also because the range of possible 'others' is so great. Those last two contested categories have to be subdivided according to reactions from different audiences: peer group, movement or party, legal system, mass media, state or outside social scientists. Such a typology none the less allows us to visualisethe realitynegotiationwhich results from every episode of deviance and control. This, in turn, allows us to ask two questions. The first is more clearly methodological:what is the status of actors' subjectivemeanings as revealedby How can these sources(interviews,publicstatements,oralhistories)? our standard claims be checked in the light of other evidence, notably the action itself? The second question is more political: under what conditions are claims actually legitimated and offered concrete political support? In the relevanthistoricaland criminologicalliteraturethese questionshave not alwaysbeen separatedout - leaving it unclear where any case would fit into my self/other typology. In his original account, for example, Hobsbawmwas more clearly concerned with the second criterion (legitimation by others) than any questions of subjective meaning. Banditryis social protest when 'it is regarded

Consciousness and legitimation

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

477

as such by the poor who consequently protect the bandit, regardhim as their champion, idealize him and turn him into a myth' (Hobsbawm, 1959: 13). He was not much interestedin what sociologists of deviancecall 'initial motivation'. Thus, 'It does not greatlymatterwhethera manbeganhis careerfor quasi-political reasonslike Giuliano ... or whetherhe simply robs becauseit is a naturalthing for an outlaw to do' (ibid.: 19). In this case popular recognition precedes (and might then cause)changes in self-recognition.The powerful, we can assume, will always be more grudging in their recognition. Their normal interest, that is, must be to depoliticise. It was, for example,obviouslymore convenientfor successivesettlersto pathologise Bushmen crime ratherthan see it as a reactionto colonial domination.But what are we to make of this extraordinary statementGordon found in a police report about a woman who killed her three boys: 'She says that she will not bring up boys in order that they have to work for white men'? The methodologicalproblem here is to do justice to social meaning without romanticallyelevating it into something we would preferit to be. Paradoxically, it is a chapter located firmly (and properly) in the section on 'Protest and Resistance' which offers the most sensitive guide to the problem of attributing political consciousness. Leroy Vail and Landeg White take a clearly subjective source: the creation of the people themselves in the form of 200 popular songs recordedin colonial Mozambique.The songs show with greatclarityand power the people's bitter hostility to the colonial order, their awarenessof abuses of power, official violence, Portuguese prodigality.Vail and White's aim is not to show the limits of this type of popular consciousness, or even to demonstrate Eric Wolf's point that 'transcendentalideological issues appear only in a very prosaicguise'. The point ratheris to show the falsenessof the contrastin African history between 'resistance' and 'collaboration'- terms which do little justice to what people thought, how they made sense of their previous experience and the realities of colonial power. In 'elevating the peasantryto its new legitimacy' the old political vocabulary was shiftedonto the economicterrain.This allows for the elevationto 'resistance' of any activity which frustratesthe operationsof capitalism- theft, desertion, or evasion,low productivity whatever.This, they say, is to do violenceto language and to beg the question of what happens when the 'same' activity is practised by the peasantryin the new revolutionarystates. Further: Even more worryingis the naivetyof so much resistance psychology,with its Humanreactions exploitation enormously to are politicalmoralising. accompanying diverse. moment gobeyond kinds organised The we the of that resistance arepolitically ormilitarily and visible tryto deduce from behaviour attitudes, their people's perceptions andcultural 'collaboin values,we findourselves areaswheretermslike'resistance', and consciousness', consciousness' thelikelackthenecessary 'false ration', 'subjective

nuances. [p. 195]

This is a severe restriction.Vail and White are surelycorrectin noting, however, that resistanceand collaborationare not alwaysthe right or the most interesting ways of classifying behaviour:

Any competentnovelistwould have no difficultyin devisingtwenty differentnarratives describing twenty different ways of coping with exploitation and each of the twenty heroes and heroines- their days mixed up with a mixtureof semi-resistance semiand collusion - would have an equal claim on our attention. [p. 195]

478

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

Legitimacy, not consciousness, occupies Terence Ranger's excellent account of the relationshipsbetween peasants and guerrillas in the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe during the seventies. His criterion for banditry is not 'lack of coherent political motivation' but illegitimacy and criminality. He describes a long and complex struggle for legitimation in which the possibilities of bandit/criminal,social bandit and guerrilla/freedom fighter were continually at stake. In the early years the choice between politics and crime ('legitimacyand animality')was this: 'which of these men with guns representedthe people and were seen to behave like heroic men; which resortedto force againstthe people and were seen to behave like beasts?'(p. 379). To gain legitimacythe guerrillas had to adopt codes of right conduct, discipline, rules against stealing from or harassingthe people. We may extract four possibilities from Ranger's historical account: (i) the unequivocalguerrilla- who is recognisedby the party leadershipand accepted as such by the peasants; (ii) the unequivocal bandit - individuals and gangs operating under cover of the war, repudiatedby the party and feared by the peasants;(iii) the fighters who are regardedby the party as guerrillasbut who are not (yet) accordedthis legitimacy by the peasants, who see them rather as bandits(becausethey breakdisciplinary rules,get drunk,areguilty of harassment); (iv) an equivocal categoryclose to social banditry- renegadeterroristswho are accepted and helped by the peasants but not recognised by the party. When the liberationmovementcameto powerafter 1980 therewas theoretically no need for guerrillas- or social bandits. Armed groups outside the service of could only be unredeemed the state, like those operatingin partsof Matabeleland, banditsand were not claimedby any partyor liberationmovement.Yet, suggests Ranger, they were, in some areas at least, accepted by the peasants:a strange return of the social bandit.

AFRICANCRIMINOLOGY

To move from radical historiography of Africa to conventional Western criminologyof Africais less like seeing the same territorywith a different guide than using a different map altogether. Until very recently this map has come from 'comparativecriminology' (usually little more than the euphemism used when Anglo-Saxon academics look at societies other than their own). In terms of this paradigmcrime in the Third World in general, and Africa in particularis conceived wholly within modernisationtheory. In this theory the Third World is seen as simply passing through the stages completed by the West in the early phases of industrialisation;crime is a result of rapid social of and modernisation, can be explainedin terms change,the by-product over-rapid of 'universalprocesses that cross cultural lines' (such as anomie, urban drift or social disorganisation). In the last few yearsthis perspectivehas been challengedby the counter-theory of radicalcriminology.6This invertsall the assumptionsof modernisation theory: Third World developmentis not simply a retardedreplayof Western European history; the dominant processes are colonialism, imperialismand dependency; crime is 'an integralally of capitalistpenetrationinto the Third World'(Sumner, 1982: 33); colonial law creates new categoriesof crime and provides labour for capital.

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

479

Like many revisionist endeavoursin their early stages, these counter-theories have sometimes been ratherfacile - as if simply using words like 'dependency' and 'modes of production' will magically lead to understanding.The theories are also more convincing when dealing with definition (the criminalisationof customary activity, the use of law to control wage labour) than behaviour. Mahiber's recent argument, for example, that 'much of the history of crime in Third World societies is a history of political conflict precipitatedby colonial law' (Mahiber, 1985: 3) turns out to be less of a challenge to conventional criminologythan she claims.She analysesthe BlackPowermovementin Trinidad as a formof'nation building'and shows how, duringthe 1970 stateof emergency, these activities threatenedthe interests of the neo-colonialelite, leading to legal repressionand criminalisation.This case might indeed show 'that the "crimes" claimedby the Trinidad Governmentin connection with the Black Power crisis were not really crimes' (Mahiber, 1985: 183). The example is familiarenough: the powerful try to delegitimatepopulardemandsfor social change by labelling them as criminal. But this tells us very little about those forms of crime not at all associated with the boycotts, protests and other unambiguously political activities of the movement. At least, however, there is here a theory and a depicted social reality which historians would recognise. In the conventional criminology of Africa not the slightesttraceof these key questionsaboutcrime and politics will be found. They cannot easily be posed within the modernisation paradigmor by the international bodies which control the cultural capital of comparativecriminology through the United Nations and similar social defence organisations. Brillon's book emergesfrom one of the most visible organisationsin this field: the Montreal-basedInternationalCentre for ComparativeCriminology which since 1970 has carried out researchin West Africa, based in the Ivory Coast. I have criticised elsewhere (Cohen, 1982) the overall direction of this type of work:the evangelicalpeddling of made-for-export Western criminologyand the vision of social controlguidedby professionals expertswho have and paternalistic to tell backward Africansocietiesaboutthe crimeproblemwhich they don't realise they have. I noted also, though, that the Centre's actual research was not insensitive to local conditions and, at best, showed a cultural relativism and a disenchantmentwith the replication of discredited Western solutions. It is this best side which is shown in Brillon'sbook.The productof collaboration with the CriminologicalInstitute at the University of Abidjan,it startswith the candid admission: 'The criminologist is ill-equipped to analyse deviance and criminalbehaviourin the Africancountries'(p. 11). Brillon recommendsinstead a new inter-disciplinary solution:'ethno-criminology'. Two separatesocial orders must be understood. First, the traditionalAfrican systems of law and justice, basedon 'indigenousancestralpractices'and studiedby 'juridicanthropologists', and then the new penal codes, judicial proceduresand social defence policies studied by Western criminology. Little of this will be news to Africanistsand, comparedwith the sophisticated theoretical genealogy of Crummey's volume, this is elementarystuff. There is the ubiquitous assumption that the same 'evolutionary process' which took centuries in Europe and America is now 'condensed' in Africa, thus allowing the clash between two social orders to be observed. There is no overall theory of colonialism or dependency and little mention of the significance of capitalist

480

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

or penetration changesin politicaleconomy.There is no senseat all of any political struggle or conflict, let alone protest, resistanceor rebellion. Ethnographiesare cited, but aside from Bohannan's early work there is no awarenessof recent anthropological theory about law, orderand conflict resolution.And, despite his own evidence to the contrary, Brillon continues to see crime and other 'social pathologies' as indicators of anomie. Despite these theoretical shortcomings, though, this is a study from which Africanistshave much to learn. They might find little new in the substance of Brillon's chapters on criminal infractionsin traditionalAfrican societies or on traditionaljuridicsystems, but the grid of Westerncriminologywhich he places over this familiarmaterialyields a surprisinglyinterestingpicture. He classifies infractions into five types - sorcery, then crimes against public authority, life and bodily integrity, morals and patrimony- concentratingon examples such as homicidein which motivation(sorcery, theft, adultery) gives the actorimmunity becausecustomary laws do not definethem as crime.He then dealswith traditional judicialprocedures- conflict resolution,vendettas,conciliation,restitution,trial by ordeal,etc. - in terms of their emphasison compensationof the victim. This again is familiarmaterial- and Brillon does not speculate on its recent appeal to Western criminologistswho seek to abolish the punitive criminal law model in favour of 'traditional'forms of conflict resolution.7 The best partsof the book,though,deal not with traditional patternsof deviance and control,but with criminology'proper'.Using originalresearchmaterialfrom Abidjanand the rest of the Ivory Coast, supplementedby data from elsewhere in francophoneAfrica, Brillon's real subject becomes the socially constructed nature of criminal statistics. Unlike Crummey's historians, whose subject is uncritical behaviour not definition,andwho areconsistently(andsurprisingly) and about using official criminal records as actual records of behaviour, Brillon correctly refuses to see statistics as reflecting 'criminality'. The model is familiar. The state system of social control (criminal law) is overlaid and imposed on the traditionalorder. But the people continue using this traditionaljurisdictionto settle disputesand conflict:this is more accessible, more comprehensible and can be used in an opportunistic way. The result: criminal statistics which mask the 'true' volume and nature of crime. This model leads Brillon into some fruitful directions.He sees crime statistics as an index of'juridic acculturation'.The formalsystem acts as a filter (political in characterbecause it aims to incriminate behaviour which does not fit the ideology of the nation state or its economic interests).The flow of acts into the into of absorption devianceand its 'conversion' crime. systemmeansthe increasing This happens through 'regulation'and 'indication' (the definitions of modern justice achieve hegemony) and what Brillon nicely calls 'magnetism':'the new institution, its attractionstrengthenedby the coercive measures conferred by politicaland legislativepower,will direct,stealand lure clientswho were formally subject to other systems or institutions' (p. 127). Magnetism in turn depends on such banal mattersas proximityof villages to etc. courts,police deploymentpatterns,localpowerstructures, The solemnfigures of comparativecriminology then - the standardcomparisonof crime rates per 100,000 of the population- tell us little aboutcriminality.To know that in 1972 the crime ratein Zairewas 107 per 100,000 and in Ivory Coast410 and in Ghana 1072, without knowinganythingabouteach flow system, gives us only what Nils

BANDITS, REBELS OR CRIMINALS

481

Christie calls 'dead data'. The same dead data form the base of standardAfricancriminologicalresearch whose 'banality' Brillon tellingly criticises. These studies deplore the absence of adequatestatistics but, instead of using them as indicatorsof the functioning of the criminaljustice system, they go on to use this 'castrated','de-Africanized' data to replicateand elaborateall sorts of (usually out-of-date)Western theories. Thus papers are still produced such as 'The role of family structure in the of development delinquentbehaviouramongjuveniledelinquentsin Lagos'.These 'prove' that broken homes 'cause' delinquency - rather than talk about social context (of families, ruralexodus, age structures)or selection process (failureof controlagencies,degreeof isolation,exposureto officialsanctions) self-regulating or nature of the delinquency (the most common arrestbeing the illegal sale of goods on the street). Such criticism should - but, of course, won't - stop the nonsense of this type of criminological research. And historians have much to learn about criminal statisticsas indicatorsof the deploymentof social control resources.8But Brillon does not travel far enough down his own theoretical track. He claims that his ethno-criminologyallows us to 'get at' all the hidden crime which is absorbed by a parallelsystem 'which leaves no tracethat would enable us to collate, assess and quantifythese crimes' (p. 148). But this begs the policy question of why we should want to do this and the theoreticalquestion of how an act can be a crime before it has reached the system which has a monopoly on this definition.

CONCLUSION

Though apparently dealingwith the same subject- crime and violence in colonial - these booksareworldsapartfromeachother:in theory,method,audience, Africa intentions and hidden politics. Yet comparingthem is more than an exercise in the sociology of knowledge,more than a study of how intellectualdiscoursesare constructed. The problemsof an 'ethno-criminology' which has no history or politics might be obvious. But what can sophisticatedsocial historiansof Africalearn from this criminology?In one sense the real value of Crummey's volume is that it is so free from the intellectualbaggageof positivistcriminology.We directlyapproach crime and banditry through the discourses of popular history and political economy without having to pass through the terrainof pathology, determinism and punishment. Seldom would theories of differentialopportunity, subculture of violence or status frustrationhave added very much. But somethingis missing. Crime in colonialAfricaconsists not just of the high dramaof bandits, highwaymen,brigands,rebels and outlaws, but the low drama of children being arrestedfor begging on the streets or stealing food from the marketstalls. These are the people - the poorest, the weakest, the most isolated - who find themselves defined as criminals. Then there are those other dramas of magic,sorcery,ritualcrime,infanticide,personalinsult, self-defence vigilanand tism. And yet anothertype of high drama:the crimes of the multinationalsand the CIA, genocide, state crime and death squads, corruption and bribery. Now, of course it is no real 'criticism' against social historians of Africa that offencesor crimes they don't talkaboutbanal,everydaydelinquencyor traditional of the powerful. These were not their subjects. But some awarenessof the bread

482

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

and butterof criminologyand the advancesin alternative criminologymight none the less help. It might prevent the cavalier assumption that because the law is political (in the sense of originating in the demands of the political economy) then all law violation is a sign of resistance,rebellion or protest. It might help understandhow notions of individualrights, privatepropertyand personalsafety are not only understoodin terms of legal domination. It will offer some useful and models to comprehendthe dialecticbetween individualacts of rule-breaking organisedideologies and systems of social control. And, above all, it will show the intractableproblems in the concept of crime.

NOTES As a guide to the theoreticaldifferencesin criminology and the sociology of deviance, I would suggest Matza (1969) and Young (1981). Recent Marxist work is representedin Greenberg(1981). 2 Crummey's in collectionoriginated a symposiumon 'Rebellionand SocialProtestin Africa'which was held at the University of Illinois in 1982. Brillon's study was first published in French under de the title Ethnocriminologie l'Afriquenoire in 1980. A model historicalaccount(influencedby Foucault)of this transitionin Britainis Garland(1985). 4 Such an account would have to deal with a ratherstrange currenttwist in radicalcriminology. The early searchfor incipient signs of resistance,heroism and rebellion in working-class criminality is now being repudiatedin favourof a realisationof the divisive, demoralisingand anti-revolutionary character crime- the factthatthe powerlessareits mainvictims.Those earlierattemptsaredismissed of as romantic, idealist and Fanonist. This emerging 'radicalrealist' position (Young, 1986) - which also appealsto E. P. Thompson, but this time for his appreciationof the historicalvictories of the rule of law - has some fascinatingimplications for popular social history. 5 The standardtexts are Clinard and Abbott (1973), Clifford (1974) and Shelley (1981). 6 See particularlySumner (1982). 7 For a key statement,see Christie(1977). Two recent collections edited by Abel (1982) and Black (1984) contain guides to this literature. account 8 Erikson's the remains best such historical Massachusetts (1966)studyof seventeenth-century of deviance and social control.

REFERENCES Abel, R. L. (ed.). 1982). The Politics of Informal Justice, 2 vols. New York: Academic Press.

study, Brillon, Y. 1985. Crime,Justiceand Culturein BlackAfrica:an ethno-criminological de Cahierno. 3. CentreInternational Criminologie Universitede Montreal. Comparee:

Black, D. (ed.). 1984. Toward a General Theoryof Social Control. New York: Academic Press. Christie, N. 1977. 'Conflicts as property', British Journal of Criminology, 17, 1-15. Clifford, W. 1974. An Introductionto African Criminology.Nairobi: Oxford University Press. Clinard, M. B., and Abbott, D. J. 1973. Crime in Developing Countries: a comparative perspective. London: John Wiley. Cohen, S. 1973. 'Protest, unrest and delinquency convergence in labels and behaviour',

International Journal of Criminology,1, 117-28. on in S. Spitzer and R. Simon (eds.), Research Law, Devianceand Social Control,vol.

4, pp. 85-119. Greenwood: JAI Press. Crummey, D. (ed.). 1985. Banditry, Rebellion and Social Protest in Africa. London: Heinemann. Erikson, K. T. 1966. Wayward Puritans: a study in the sociology of deviance. New York: John Wiley. Garland, D. 1985. Punishment and Welfare: a history of penal strategies. London: Gower. Greenberg, D. F. (ed.). 1981. Crime and Capitalism in Marxist Criminology. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1982. 'Western crime control models in the Third World: benign or malignant?',

BANDITS, REBELSOR CRIMINALS

483

Hobsbawm, E. J. 1959. Primitive Rebels.New York: Norton. towards Horowitz,I. L., and Liebowitz,M. 1968. 'Socialdevianceandpoliticalmarginality: a redefinition of the relationshipbetween sociology and politics', Social Problems, 15, 288-96. in the Mahiber, C. 1985. Crimeand Nation-Building the Caribbean: legacyof legalbarriers. Cambridge,Ma.: SchenkmanPublishing Co. Matza, D. 1969. BecomingDeviant. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Pearson, G. 1975. The Deviant Imagination.London: Macmillan. Crises: 1978. 'Goths and vandals- crime in history', Contemporary crime,law, social policy, 2 (2), 119-40. and Schur,E. M. 1980. ThePoliticsof Deviance: stigmacontests theusesofpower.Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. the and Shelley, L. 1981. CrimeandModernisation: impactof industrialisation urbanisation on crime. Carbondale:Southern Illinois University Press. Sumner, C. 1982. 'Crime, justice and underdevelopment: beyond modernisationtheory', in C. Sumner (ed.), Crime, Justice and Underdevelopment, 1-39. London: pp. Heinemann. Young, J. 1981. 'Thinking seriously about crime: some models of criminology', in M. in Fitzgeraldet al. (eds.), Crimeand Society:readings historyand theory,pp. 220-48. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1986. 'The failure of criminology: the need for a radical realism', in R. Mathews and J. Young (eds.), Confronting Crime, pp. 4-30. London: Sage Publications.

Resume

Bandits, rebelles et criminels: histoire africaine et criminologie occidentale

Cet articlepasseen revueles differentsthemes evoquesdans deux livresrecentsqui traitent de la criminalit6en Afrique. Le premier, Banditisme,Rebellion Protestation et Socialeen Afrique, repr6senteun recueil de dix-sept etudes historiques rassemblees par Donald Crummey sur la criminalite, le banditisme, la protestationet la rebellion dans l'Afrique coloniale.Le second, Criminalite, dansl'Afrique Noire,constitueen etude Justiceet Culture criminologiquedu crime et de la justice dans les societes africainescontemporaines. La revue commence par un bref resume de la manieredont on accordaitau crime une signification politique dans les diverses 'nouvelles' criminalit6squi se d6velopperenten Occident au cours des vingt dernieresannees. Ces themes apparaissentsous des formes similaires dans l'histoire africaine:la question de d6couvrirla signification politique du crime 'ordinaire';la cat6gorisation 'bandit social' telle qu'elle fut a l'origine suggeree du par Hobsbawm;la relationentre la motivationsubjectiveet la legitimationveritable.Tous ces themes sont presents dans le recueil de Crummey. Le livre de Brillon pr6senteun r6cit anthropologiquede la criminaliteconventionnelle en Afrique.II s'agitbeaucoupmoins d'un ecritpolitiquesur la signification la criminalite de que d'une explication de la nature socialement construite des statistiques officielles de

la criminalite.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Nature Scope and Importance of CriminologyДокумент28 страницNature Scope and Importance of Criminologyfaisal Naushad82% (11)

- Overview of Criminal InvestigationДокумент30 страницOverview of Criminal InvestigationDonbert AgpaoaОценок пока нет

- Chairperson 2009 Bar Examinations Committee: Criminal LawДокумент4 страницыChairperson 2009 Bar Examinations Committee: Criminal LawMaria Cristina MartinezОценок пока нет

- PP V de Guzman - Admissibility and RelevanceДокумент2 страницыPP V de Guzman - Admissibility and RelevanceElyn ApiadoОценок пока нет

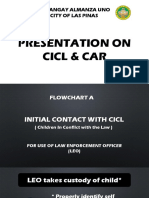

- Presentation On Cicl & Car: Barangay Almanza Uno City of Las PinasДокумент33 страницыPresentation On Cicl & Car: Barangay Almanza Uno City of Las PinasCorics Herbuela100% (1)

- Iobc-Cic-Final-Briefing-New Jan 5 2021 Final NewДокумент102 страницыIobc-Cic-Final-Briefing-New Jan 5 2021 Final NewHamsel MandaganОценок пока нет

- Social Interac Tionist Perspectives On Aggression Violence:: B. James TДокумент10 страницSocial Interac Tionist Perspectives On Aggression Violence:: B. James TIuliana OlteanuОценок пока нет

- Tokunbo and Chinco Economies in Nigeria Rethinking Encounters and Continuities in Local Economic Transformations 164-352-1-PBДокумент22 страницыTokunbo and Chinco Economies in Nigeria Rethinking Encounters and Continuities in Local Economic Transformations 164-352-1-PBKudus AdebayoОценок пока нет

- African Scholarship and Visa - Challenges For Nigerian AcademicsДокумент1 страницаAfrican Scholarship and Visa - Challenges For Nigerian AcademicsKudus AdebayoОценок пока нет

- How Not To Write A PHD Thesis - General - Times Higher EducationДокумент6 страницHow Not To Write A PHD Thesis - General - Times Higher EducationKudus AdebayoОценок пока нет

- Soyinka's Smoking Shotgun - The Later SatiresДокумент9 страницSoyinka's Smoking Shotgun - The Later SatiresKudus AdebayoОценок пока нет

- Questionare For Criminal Law 2Документ4 страницыQuestionare For Criminal Law 2Mika SantiagoОценок пока нет

- Elements of A Crime: Actus Reus: Introducing Terminology and ClassificationsДокумент9 страницElements of A Crime: Actus Reus: Introducing Terminology and ClassificationsCharlotte GunningОценок пока нет

- CA 2 TerminologiesДокумент4 страницыCA 2 TerminologieskatemonroidОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Examination in Criminal SociologyДокумент11 страницDiagnostic Examination in Criminal SociologyChezca TaberdoОценок пока нет

- Cep CrimsocnotesДокумент71 страницаCep CrimsocnotesHarrison sajorОценок пока нет

- Concept of Open Prison System As A Correctional SystemДокумент16 страницConcept of Open Prison System As A Correctional SystemPAVANKUMAR GOVINDULAОценок пока нет

- Victoria Crimes Act 1958Документ892 страницыVictoria Crimes Act 1958Harry_TeeterОценок пока нет

- Us Prison System Argumentative Essay Final DraftДокумент8 страницUs Prison System Argumentative Essay Final Draftapi-395015790Оценок пока нет

- Mob Boss Agnello, Raffaele c1829-1869Документ13 страницMob Boss Agnello, Raffaele c1829-1869Scotty Ilyich StirnerОценок пока нет

- Barangay Justice System (BSJ)Документ3 страницыBarangay Justice System (BSJ)Ayesha LanuzaОценок пока нет

- Test Bank For Criminological Theory Context and Consequences 7th Edition J Robert Lilly Francis T Cullen Richard A BallДокумент12 страницTest Bank For Criminological Theory Context and Consequences 7th Edition J Robert Lilly Francis T Cullen Richard A Ballfreyagloria1wa4Оценок пока нет

- Malana vs. People, GR No. 173612 (Case) PDFДокумент14 страницMalana vs. People, GR No. 173612 (Case) PDFjomar icoОценок пока нет

- Homicide NotesДокумент16 страницHomicide NoteskjdslasbdlОценок пока нет

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 12/01/15Документ7 страницPeoria County Booking Sheet 12/01/15Journal Star police documentsОценок пока нет

- Napolis Vs CA, GR No. L. 28865, 28 February 1972Документ1 страницаNapolis Vs CA, GR No. L. 28865, 28 February 1972Monica Feril100% (1)

- The Advantages of The Legalization of Death Penalty All Around The World.Документ6 страницThe Advantages of The Legalization of Death Penalty All Around The World.Manaf MahmudОценок пока нет

- A Study of Rehabilitative Penology As An Alternative Theory of PunishmentДокумент13 страницA Study of Rehabilitative Penology As An Alternative Theory of PunishmentAnkit ChauhanОценок пока нет

- Cases (Criminal Law) : Inmates of New Bilibid Prison vs. DOJ Sec, GR 21719, June 25, 2019Документ4 страницыCases (Criminal Law) : Inmates of New Bilibid Prison vs. DOJ Sec, GR 21719, June 25, 2019Hannah Tolentino-DomantayОценок пока нет

- Domestic ViolenceДокумент2 страницыDomestic ViolenceKash AhmedОценок пока нет

- Homicide CaseДокумент18 страницHomicide CaseJj Ragasa-MontemayorОценок пока нет

- Human Resource Planning For PrisonersДокумент483 страницыHuman Resource Planning For PrisonersMridul SrivastavaОценок пока нет

- P.D. 1689 - No Bail Syndicated EstafaДокумент1 страницаP.D. 1689 - No Bail Syndicated EstafaColoma IceОценок пока нет

- State of Utah Board of Pardons and Parole StatementДокумент2 страницыState of Utah Board of Pardons and Parole StatementKUTV 2NewsОценок пока нет