Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

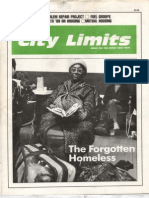

City Limits Magazine, March 2002 Issue

Загружено:

City Limits (New York)0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

261 просмотров44 страницыCover Story: Shelter Skelter by Jill Grossman.

Other stories include Kendra Hurley on coming help for immigrants in foster care; Nora McCarthy on certain welfare families' problems getting sufficient help to pay rent; Wendy Davis on the CUNY School of Law's looking to the bar exam to figure out what activist attorneys are made of; Alyssa Katz on the city's housing crisis, as demonstrated by people's experiences at the Emergency Assistance Unit; Wendy Davis on whether even the most understanding judge can make mentally ill defendants obey the law; David Jason Fischer's book review of "Hands to Work: The Stories of Three Families Racing the Welfare Clock" by LynNell Hancock; David Hochman on New York's foundations and the tactics they should be taking; and more.

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документCover Story: Shelter Skelter by Jill Grossman.

Other stories include Kendra Hurley on coming help for immigrants in foster care; Nora McCarthy on certain welfare families' problems getting sufficient help to pay rent; Wendy Davis on the CUNY School of Law's looking to the bar exam to figure out what activist attorneys are made of; Alyssa Katz on the city's housing crisis, as demonstrated by people's experiences at the Emergency Assistance Unit; Wendy Davis on whether even the most understanding judge can make mentally ill defendants obey the law; David Jason Fischer's book review of "Hands to Work: The Stories of Three Families Racing the Welfare Clock" by LynNell Hancock; David Hochman on New York's foundations and the tactics they should be taking; and more.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

261 просмотров44 страницыCity Limits Magazine, March 2002 Issue

Загружено:

City Limits (New York)Cover Story: Shelter Skelter by Jill Grossman.

Other stories include Kendra Hurley on coming help for immigrants in foster care; Nora McCarthy on certain welfare families' problems getting sufficient help to pay rent; Wendy Davis on the CUNY School of Law's looking to the bar exam to figure out what activist attorneys are made of; Alyssa Katz on the city's housing crisis, as demonstrated by people's experiences at the Emergency Assistance Unit; Wendy Davis on whether even the most understanding judge can make mentally ill defendants obey the law; David Jason Fischer's book review of "Hands to Work: The Stories of Three Families Racing the Welfare Clock" by LynNell Hancock; David Hochman on New York's foundations and the tactics they should be taking; and more.

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 44

CIVIL OBEDIENCE: SILENCE IN THE STREETS

NEW YORK'S URBAN AFFAIRS NEWS MAGAZI

EDITORIAL

25 YEARS OF

PLENITUDE

WOW-WE MADE IT. As

City Limits wraps up its

25th anniversary celebration,

most of that "we," dear reader, is

you. (The current crew here can boast about a

lot of things, but longevity's not one of them: In

1976, I was eight years old, and I'm the old lady

on the editorial staff.) More than anything else,

this milestone is testament to the power of

action and ideas to change the world. This

magazine has had the privilege of watching the

rest of you literally remake New York City.

Government support to reclaim abandoned

buildings for the people of the city. The Com-

munity Reinvestment Act. The maturing of

community development corporations into vital

neighborhood resources (and, occasionally, into

unaccountable fiefdoms). A social service infra-

structure that has the potential-so under-real-

ized by the politicians providing the funding-

to reliably address communities' basic needs.

Building green spaces and curbing discriminato-

ry dumping of the facilities no one else wants.

Welfare rights organizing, insurgency against

corrupt labor unions, and homeless people

demanding decent treatment. Supportive hous-

ing-<lignity by design. Bringing domestic vio-

lence into the public eye, and victims to help;

undoing the worst abuses of foster care. Only a

tour through the back issues of City Limits can

do justice to all of it (which you're welcome to

take anytime-just drop us a line!).

But just because you've been doing the hard

work doesn't mean City Limits just sat on the

sidelines taking notes. You know this already, 'or

you wouldn't be reading the magazine right now:

The very act of supplying reliable, in-depth

information about how the world really works-

and particularly about the wielding of power, for

good and for ill-is itself a mighty work of

activism. That's never been more true than today.

In a media environment where the bonom line

increasingly dictates content-and serious, influ-

ence-oriented magazines, from Neighborhood

\Wirks to Lingua Franca to the The Sciences, have

shut down after proving financially unviable-

the power of independent, uncompromised and

informed communication about the issues vital

to civil society is a precious resource, and one in

which entire communities have heavy stakes.

This magazine has a well-deserved rep for

obsessing over New York City's problems. But

City Limits has also always dug deep for viable

solutions, particularly ones that fall outside the

realm of existing political interests. Those are

the basic elements the magazine and the City

Limits Week!) will continue to work with into

the future.

The question is, how do we deliver on that

potential? How do we do justice to the possibil-

ities of a free press and the power it has to speak

to those who the public trusts to make New

York a glorious, livable and just city? How can

the tools of journalism provide ammunition for

others who share that agenda? We ask ourselves

these questions every week at editorial meetings.

But the answers the staff here takes most seri-

ously are the ones we get from the people who

really know what's going on-who actually live

and work in New York's neighborhoods.

With the launch of an entirely overhauled

web site this month-www.citylimits.org-

we're extending the reach of our work, to make

it more accessible, more plentiful and, above

all, more useful to people who rely on the

information and insights City Limits provides.

We're going to keep asking questions-and

never be satisfied with the answers until we all

see results.

-Alyssa Katz

Editor

Cover photo by Joshua Zuckerman; mother and son, names unknown, who have been seeking help at the Emergency Assistance Unit for two years.

HOME IMPROVEMENT

SOME OF YOU MAY HAVE SEEN the article "Eyries of Left and Right Dissect the

City's Ills" in the New York limes this January. The City section took the oppor-

tunity of our 25th anniversary to profile of the work of this magazine and that

of our philosophical archrival , the Manhattan Institute's City Joumal. The arti-

cle, in our opinion, did a good job of capturing the differing voices of our two

publications: We're a news organization. They're a journal. Their readers are

the powerful. Ours hold the powerful accountable. We called them "rhetoricaL"

They called us "something to wrap fish."

Ah, what fun. I only bring this up because the article also inadvertently

exposed some divisions and misunderstandings within our own ranks. In the

piece, I was quoted saying the copy in City Limits "wasn't political" in its early

days, back when the magazine was founded in 1976. One of our board mem-

bers, the investigative journalist (and former City Limits editor) Tom Robbins,

e-mailed immediately to remind me-and our relatively young staff-that

nothing could be further from the truth.

Back in the 1970s, when the city was reeling from financial problems and

white flight, city planners were actively considering a policy called "planned

shrinkage"-a clever way of, well, just giving up on the boroughs' most impov-

erished, arson-riddled neighborhoods. The founders of City Limits fought

this ... on the streets, organizing tenants and saving our all-important apartment

buildings from landlords looking to bum them down and city officials eager to be

rid of the people who inhabited them. ''Those groups waged what was an

INTENSELY political struggle," Tom reminded me. "It was a battle for survivaL"

Of course, I knew this, even if I didn't say it. In truth, the the mere act of pub-

lishing City Limits was a political act. .. and the movement that surrounded our

magazine's birth resulted in, literally, billions of dollars of new funding for hous-

ing construction and rehabilitation. Thousands of families in New York City now

live in safe, warm homes, not just because City Limits covered the nuts and bolts

details of how to fix and finance housing, but because this magazine's founders

were an active part of a political movement. Thanks to our predecessors' incred-

ible dedication, both of those are traditions we maintain to this day.

-Kim Nauer

Publisher

City Limits relies on the generous support of its readers and advertisers, as well as the following funders: The Adco Foundation, The Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, The Child Welfare Fund, The

Unitarian Universalist Veatch Program at Shelter Rock, Open Society Institute, The Joyce Mertz-Gilmore Foundation, The Scherman Foundaton, JPMorganChase, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The

Booth Ferris Foundation, The New York Community Trust, The Taconic Foundation, LlSC, Deutsche Bank, M& T Bank, The Citigroup Foundation.

FEATU R ES

13 CLASSROOM ADVERSARIES

It's been know as a training ground for activist attorneys since it

was founded in 1983. Today, CUNY School of law hosts a new

struggle-pragmatism versus radicalism.

By Wendy Davis

SPECIAL FEATURE: HOMELESS FAMILIES

18 LOSING HOME RUN

Most families who seek emergency shelter aren't classified

as homeless. But what else do you call it when

you can't find a place to live?

By Alyssa Katz

22 SHELTER SKELTER

Families can't find homes they can afford, so the city is

paying landlords $3,000 a month to lodge them.

Only in New York.

By Jill Grossman

CONTENTS

5 FRONTLINES: WANTED: GAMBLERS TO CLOSE BUDGET GAP .... FOSTER KIDS GET

DOCUMENTED ... TRIPLE THREAT GRABS MIC .... KILLING KIPS BAY'S AFFORDABILlTY .... PRAGMATISM

FOR ALBANY ACTIVISTS? .... LAYING CLAIM TO TAX CREDITS .... SOCIAL WORKERS SOUND OFF

INSIDE TRACK

1 0 HOSED IN HOUSING COURT

A major restructuring of housing court was supposed to be good for both

landlords and tenants. Guess who won and who lost. By Nora McCarthy

INTElliGENCE

26 THE BIG IDEA

Everyone applauds the concept of treatment instead of jail.

Will New York's experiment with mental health courts follow drug

courts' success? By Wendy Davis

28 CITY LIT

Hands to Work: The Stories of Three Families Racing the Welfare Clock,

by LynNell Hancock. Reviewed by David Jason Fischer

Washington's New Poor Law: Welfare "Reform" and the Roads Not

Taken, 1935 to the Present, by Gertrude Schaffner Goldberg and Sheila

D. Collins. Reviewed by Eleanor J. Bader

MARCH 2002

30 MAKING CHANGE

Civil disobedience seemed tactless in the days immediately

following September 11. Several months later,

it is still MIA. By Hilary Russ

32 NYC INC.

Fighting poverty in the city would take a big step forward if New York's

foundations targeted job creation instead of just patching

neighborhood problems. By David Hochman

2 EDITORIAL

4 LETTERS

37 JOB ADS

40 PROFESSIONAL

DIRECTORY

42 OFFICE OF THE

CITY VISIONARY

3

LETTERS

DEFENDING THE FORT

With "Crossing the Line" Uanuary 2002],

Sasha Abramsky has written an unbalanced

article on crime and policing in Fort Greene.

His conclusion-that people don't care about

what's happening in the projects-is mislead-

ing and wrong. This 26-year resident and

homeowner of Fort Greene would have him

poll the people in Ingersoll and Walt Whit-

man Houses. Has crime been dramatically

reduced where they live? I bet a big majority

would say yes and that the statistics would

back them up.

-Phillip A. Saperia

Fort Greene, Brooklyn

DEFENDING THE FINEST

About your article "Crossing the Line, " it

looks to me like the cops are hassling the right

people, those who currently are--or were for-

merly-bad guys.

Right on, brother!

If some of those complaining aren't criminals

but dress like them, I suggest a change in dress.

To hell with the bad guys.

I'm a citizen tired of being hassled by scum-

bags in Vallejo. They don't have any respect for

themselves, let alone me.

-Michael D. Setty

Vallejo, CA

PUSH-OUT PIECE PRAISED

The entire adult education community in

New York City is abuzz with talk of the com-

prehensive, well-written, superb article done by

Mark Greer, "Learning Disabled" [February

2002] addressing the issue of push-outs from

local high schools. Kudos to Mark and the City

Limits staff for tenacity in ferreting out the dev-

astating issues facing youth, adults and educa-

tional programs locally. We are making this arti-

cle required reading for new teachers, tutors,

and for our staff, funders and board members,

and sharing it with our state Department of

Education representatives and local officials.

Thank you again for your consistency and

excellent reporting that deals with the difficult

issues facing New Yorkers.

-Marguerite Lukes

Literacy Assistance Center

Building a Better New York

Now More Than Ever

4

For over 30 years, Lawyers Alliance has provided free

and low-cost business law services to nonprofits with

programs that are vital to the quality of life in New York

City. Now we are committed to helping nonprofit groups

that are directly affected by the terrorist attacks on the

World Trade Center, and nonprofits offering grief coun-

seling, job placement activities, fundraising and other

disaster relief services. Our staff and pro bono attorneys

can help with contracts, employment, corporate, tax,

real estate and other non-litigation legal needs so that all

New Yorkers can continue to recover from the tragedy.

Please call us or visit our website for more information.

330 Seventh Avenue

New York, NY 10001

212 219-1800

www.lany.org

Lawyers Alliance

for New York

Building a Better New York

CITY LIMITS

Volume XXVII Number 3

City Limits is published ten times per year, monthly except bi -

monthly issues in July/August and September/October, by the

City Limits Community Information Service, Inc., a nonprofit

organization devoted to disseminating information concerning

neighborhood revitalization.

Publisher: Kim Nauer nauer@citylimits.org

Associate Publisher: Anita Gutierrez anita@citylimits.org

Editor: Alyssa Katz alyssa@citylimits.org

Managing Editor: Tracie McMillan mcmillan@citylimits.org

Senior Editor: Annia Ciezadlo

Senior Editor: Jill Grossman

annia@citylimits.org

jgrossman@citylimits.org

Associate Editor: Matt Pacenza matt@citylimits.org

Contributing Editors: James Bradley, Neil F. Carlson, Wendy

Davis, Michael Hirsch, Kemba Johnson,

Nora McCarthy, Robert Neuwirth

Design Direction: Hope Forstenzer

Photographers: Simon Lee, Gregory P. Mango, Jake Price

Contributing Photo Editor: Joshua Zuckerman

Contributing Illustration Editor: Noah Scalin

Intern: Patrick Sisson

General EMail Address: citylimits@citylimits.org

CENTER FOR AN URBAN FUTURE:

Director: Neil Kleiman neil@nycfuture.org

Research Director: Jonathan Bowles jbowles@nycfuture.org

Project Director: David J. Fischer djfischer@nycfuture.org

BOARD OF DIRECTORS'

Beverly Cheuvront, Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute

Ken Emerson

Mark Winston Griffith, Central Brooklyn Partnership

Celia Irvine, Legal Aid Society

Francine Justa, Neighborhood Housing Services

Andrew Reicher, UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Ira Rubenstein, Emerging Industries Alliance

Makani Themba-Nixon

Karen Trella, Common Ground Community

Pete Williams, National Urban League

Affiliations for identification only.

SPONSORS:

Pratt Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Subscripti on rates are: for individuals and community

groups, $25/Dne Year, $39/Two Years; for businesses, founda-

tions, banks, government agencies and libraries, $35/Dne

Year, $50/Two Years. Low income, unemployed, $IO/Dne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article contributions.

Please include a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return

manuscripts. Material in City Limits does not necessarily reflect

the opinion of the sponsoring organizations. Send correspon-

dence to: City Limits, 120 Wall Street, 20th FI. , New York, NY

10005. Postmaster: Send address changes to City Limits, 120

Wall Street, 20th FI. , New York, NY 10005.

Subscriber inquiries calk 1-800-783-4903

Periodical postage paid

New York, NY 1000 I

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

PHONE (212) 479-3344/FAX (212) 344-6457

e-mail: citylimits@citylimits.org

On the Web, www.citylimits.org

Copyright 2001. All Rights Reserved. No portion or por-

tions of this journal may be reprinted without the express

permission of the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI 48106.

CITY LIMITS

..

FRONT LINES

Joshua Zuckerman

If I Had A Gambling Problem

REVEREND DUANE MOTLEY'S EARS PERKED UP when he first heard the

twangy rhythms emanating &om his TV set. There he saw the cheery

faces of working-class New Yorkers-barbers, diner patrons, firemen and

farmers-singing an infectious tune, "If I Had A Million Dollars." It was

an advertisement for the New York State Lottery's premier game, Lotto.

"What a perfect ad," fumes Rev. Motley, the director of New Yorkers for

Constitutional Freedoms, an anti-gambling lobbying group. "It's polished,

yet humble. It's perfect for taking money &om the poor."

And it's worked. State Lottery Division spokesperson Carolyn Hapeman

says sales of lottery tickets have gone up "significantly" since the Million

Dollars campaign began last October.

The brilliant ad campaign, the centerpiece of a $20 million annual ad

budget, wasn't the state's only big new gambling push last fall . On Hal-

loween, the state legislature and Governor Pataki agreed to a sweeping

gambling expansion law that makes New York the state with the most

legal gambling outlets east of the Mississippi.

They agreed to join the Big Game, an eight-state lonery with jackpots

up to $363 million. They approved video lottery terminals in the state's

horse-racing tracks and in six Native American casinos upstate. Those

new gambling initiatives, claimed the governor, will add $1 billion annu-

ally to the state treasury.

MARCH 2002

Lottery ticket sales already account for about $1.45 billion a year in

state revenues. Who actually foots the bill? According to academic stud-

ies, working-class and poor people spend significantly more on the

games than the wealthy. A 1995 Newsday investigation found that lonery

spending as a percentage of income statewide was eight times higher in

low-income neighborhoods than in those with the highest incomes.

Lonery officials so&en the unseemly image of what's effectively a huge

tax on the desperate by directing lottery revenues to education budgers--

$145 million &om the Big Game, for example. But behind those big num-

bers lies a muddier truth. The state education budget won't grow once the

Big Game is introduced, acknowledges Hapeman; "it just means that the

lottery's contribution to the state's education fund will be that much larger. "

The debate over gambling has been dominated by the wagering indus-

try's money. They paid Albany lobbyists nearly $2.5 million between Jan-

uary and August of last year, according to state records.

The voices that oppose gambling don't come &om those corners that

typically defend the poor. It's a moralist movement, led by Rev. Motley and

conservatives like State Senator Frank Padavan (R-Queens). "The hypocrisy

of spending money to promote these games to people already addicted is

sraggering," says Sen. Padavan. "The legislature and the Governor-the

most pro-gambling in history-should be ashamed. " -Matt Pacenza

5

FRONT llNES

Immigrants in

foster care may

finally get help

getting legal.

By Kendra Hurley

GISELLE JOHN STILL REMEMBERS the night seven

yeats ago when a city social worker and a police

officer knocked on the door of the Brooklyn

aparrment she shared with some family friends.

John, not quite 16 at the time, was an undocu-

mented immigrant from Trinidad. A year earlier,

her mother had brought her to the United States

to escape years of abuse from the girl's father. Her

mother lefr John with some friends in New York

City and quickly returned to Trinidad.

When the caseworker from the city's Admin-

istration for Children's Services showed up,

6

John was certain the authorities had discovered

her secret-that she was in the country ille-

gally-and had come to ship her back to

Trinidad. So she bolted, leapt down three flights

of stairs to the street. "I was more afraid of what

would happen to me if I went back to Trinidad

than if I stayed here and hid from the authori-

ties, " remembers John, now 23 and an advocate

for foster children at Voices of Youth, a project

of the nonprofit Youth Communications.

They quickly caught up with her, and placed

her in a temporary group home, where she kept

her immigration status a secret for four months.

A caseworker soon discovered she was illegal-

she does not know how-and from then on,

social workers and lawyers entrusted to keep chil-

dren safe did more to instill fear in her than to

help her ease into life in the United States. An

attorney for the Administration for Children's

Services asked a Family Court judge to send her

back to Trinidad. The judge refused. A city social

worker warned her that if she stayed in foster care

she could cause a war between Trinidad and the

U.S. "They said, 'What would happen if

Trinidad found out we had one of their people?'"

John remembers. "I totally believed them."

Card Me

But never during her first few years in foster

care did the caseworkers offer to help her

become a legal United States resident. Little did

they seem to know that under a 1990 federal

law, immigrant children in foster care can apply

for permanent residency as a "Special Immi-

grant Juvenile." Congress wrote the legislation

in response to concerns that without the ability

to work legally, immigrant young adults would

leave foster care unable to support themselves.

Around the country, however, word of the

provision, and how to put it to use, has yet to

trickle down to most service providers. "You ask

clients if they have had sexual abuse, if they're

drinking alcohol, and yet too ofren you don't ask

them where they were born, " says Max Moran,

a social worker with Seamen's Society for Chil-

dren and Families, a private agency overseen by

ACS. In fact, Ron Cerreta from the Door, one of

the few organizations in New York City that

provides legal services for foster teens, estimates

that in the fust five years afrer Congress enacted

the residency provision, less than 100 foster chil-

dren a year were approved. In New York City, he

says, only about 50 immigrant foster kids are

made permanent residents annually. While it is

not known how many of the 1,000 New York

young adults who leave foster care each year are

immigrants, the number, child advocates esti-

mate, is much more than 50.

John was one of the lucky few, having read

an ad for The Door's services in a magazine. "I

had to take the initiative," she remembers. It

paid off; at age 19, she got her green card.

For every such success story, however, there

are many others who leave foster care to live on

their own without the right ro work legally,

receive financial aid for college, access heal th

insurance or public assistance. "They teach me

how ro cook and clean," Giselle says of the life

skills classes the foster care system provides for

teens. "But that's not on the top of my list

when I can't go to college ifI don't have a green

card, and when I can't get a job."

That could soon change, however. Afrer con-

ducting a year-long study of immigrants in the

city's foster care system, the Immigration and

Child Welfare Project, a coalition of child wel-

fare advocates, convinced the Administration for

Children's Services to try to make immigration a

regular part of foster care workers' vocabularies.

In January, ACS hired the project to train the

city's child welfare workers on the ins and outs of

CITY LIMITS

the nation's immigration system. Under the $40,000

contract, child welfare workers with expertise in these

issues will spend a year teaching about 720 casework-

ers everything from how to decipher immigration

papers and determine a client's immigrant status, to

where to refer foreign-born kids for help when they

aren't eligible for government support to how to apply

for a green card.

This training will mark the first time the city has

given its foster care workers an extensive how-to on

dealing with immigrant children and families.

Without this training, the results have at times been

disastrous for kids, says Ilze Earner, founder and direc-

tor of the Immigration and Child Welfare Project.

Nationwide studies show that many former foster kids

end up homeless and on welfare. One such study, by

Mark E. Courmey at the University of Wisconsin,

found that 32 percent of young adults who'd been out

of care for 12 to 18 months were receiving public assis-

tance, and only two-fifths of them were employed. For

kids who are not legal residents, collecting welfare and

working, at least legally, are not options. Instead, they

must rely on friends, or on the families from whom

they were taken away, sometimes returning to the dan-

gerous situations that put them in foster care in the

first place. John knows of one young man who left fos-

ter care without working papers, gOt in trouble with

the law, and was deported to his home country.

Getting legal residency is not the only thing Earner

plans to focus on in the trainings. During her 20 years

in social work, she has seen cultural misunderstandings

lead caseworkers to remove a child from a home

because it was allegedly overcrowded. In other cases,

illegal immigrant families who've had trouble putting

food on the table or required medical attention have

lost a child to foster care because they couldn't apply

for public assistance to keep the family together.

The immigration project expects the training,

slated to start this summer, to put an end to some of

these complications. When caseworkers do help foster

kids become legal residents, Earner says they some-

times lose documents, like birth certificates and Social

Security cards, that are critical to the green card appli-

cation process. Or they wait until just months before

a foster child is scheduled to leave the system to start

the residency application process, which usually takes

two to three years. Once a child leaves foster care, by

age 21 in New York, he is no longer eligible.

In those cases, "Immigration has no obligation to

give them an appointment just because they're about

to age out," says Ron Cerreta of The Door. "Their

reason is, ' You should have gotten it to us sooner.'

And that's right. But who was responsible for getting

it to their arrention in the first place? Foster care."

Kendra Hurley is editor o/Foster Care Youth United,

a magazine written by and for teenagers in foster care

and published by Youth Communications.

MARCH 2002

FRONT LINES

Gifted Rap

FOR A WOMAN WHO RAPS AND HANDLES A MIC in front of late-night crowds, a few indifferent

bureaucrats are no big deal. Tomasia Kastner, activist, educator and hip-hop performer, knows a

thing or two about winning over a tough audience.

The energetic Kastner, 28, runs Elevated Urban Arts and Education, a hip-hop poetry and arts

workshop at the Robert F. Wagner School of Art and Technology in Queens. With Elevated, kids at the

alternative high school rhyme, write, dance, design and make videos as a way to deal with some of

their daily realities, from crime and poverty to the universal hassles of growing up.

None of that could happen without Kastner's backstage wrangling for funding, placating teach-

ers who get paid late, and struggling for enough cash to buy music and computer equipment. "It

takes a special kind of person and a special kind of artist to deal with a New York City public school

district," says Toni Blackman, a fellow performer who teaches writing at Elevated. ''Tomasia does not

mind a little perspiration."

Kastner says she decided to dedicate her life to activism after an eye-opening trip to Ghana while

an anthropology student at SUNY Binghamton. Seeing the desperate poverty and racism in Ghana

made her think more critically about what was happening back at home. But, she adds, the seeds for

her work really started to germinate while growing up as the child of an Italian and black mother and

a Dutch-German father in a white Rockland County suburb. "I feel issues of racism very personally,

such that I can't really be comfortable unless I'm working to resolve them," she says.

Today, when not in the classroom, Kastner works with W.E.R.l.S.E.- Women Empowered Through

Revolutionary Ideas Supporting Enterprise-the nonprofit women's artists collective she co-founded to

give independent female artists the means to raise money and a place to perform. In her limited off-

hours, she has been able to get out her own messages about gender and racial equality, rapping and

DJing under the name infiniTEE.

Next, Kastner plans to expand Elevated to other schools. Her work enables her to reach kids who nor-

mally feel alienated by regular school subjects, she says: "I wanted to have a more proactive approach.

I wanted to create something rather than react and tear something down." -Amanda Cantrell

7

FRONT llNES

HOUSING

Phipps-ed Off

A FEW DECADES AGO, it was not uncommon for

nonprofit housing developers to partner with

investors to fund their projects. But one of the

city's oldest affordable housing managers never

expected this arrangement could threaten its

affordable housing business.

With financial support from 66 individual

investors, Phipps Houses built Henry Phipps

Plaza West 28 years ago as part of the state's

Mitchell-Lima program, which provided low-

interest loans and tax breaks in exchange for

developing low- and middle-income housing.

Since then, the 894-apartment complex on

Manhattan's Second Avenue berween 26th and

29th streets has been home to a mix of work-

ing-class families and senior citizens.

Nothing lasts forever, though. In the case of

Mitchell-Lama buildings, the state required

developers to keep rents low for 20 years. At that

point, landlords can "buy our" of the program

and get back the bulk of their profits-millions

in Phipps Plaza's case-and raise rents to market

rate. Over the last 15 years, more than 30 devel-

opers reportedly have done so, and Phipps

Houses looks to be next-much to its dismay.

In 1989, seven years before Phipps Plaza

West's contract came up for renewal , Phipps'

investors told the nonprofit developer they

wanted the buildings out of Mitchell-Lama.

Phipps resisted. A decade later, the group

found itself in court, sued by its investors.

At that point, the future did not look good. "I

knew we would never change their minds, " says

Adam Weinstein, president of Phipps Houses.

But, last month, after three years of negotiating, a

settlement was reached: As early as this summer,

the building will leave Mitchell-Lama. Because

the building has federal mortgage subsidies, ten-

ants who qualifY for Section 8 vouchers-aIIow-

OPEN CITY

Mayita Mendez

Ramapo Anchorage Camp for Inner-City Kids, Rhinebeck, NY, July 2000

8

ing them to pay only 30 percent of their income

in rent-<:an start using them immediately.

"Management will assist households to fmd

ways they can qualifY, " says Weinstein. He esti-

mates berween 70 and 80 percent of the ten-

ants at Phipps Plaza will be found eligible.

The tenants are less confident. When the own-

ers of Waterside, an ex-Mitchell Lama building on

the East River, made that same arrangement, only

20 percent of the residents qualified for vouchers.

For the rest, rent hikes were set at 9 percent a year.

So some state legislators are ttying to do what

they can, given that there are 260 Mitchell-Lama

buildings in the city and 422 statewide. Assem-

blymen Steve Sanders, Edward Sullivan and

Scott Stringer have drafted bills to extend the

buyour limitation period and to make Mitchell-

Lamas rent-stabilized. But, given Republican

opposition, even that does not look promising.

Says Sanders, "I don't see any program in the

future to replace Mitchell-Lama."

-Alex Ginsberg

CITY LIMITS

HOUSING

Out of Control

THE STATE'S RENT STABILIZATION laws don't

expire until 2003, but tenant advocates looking

ro rweak the regulations are treating this year's

elections as a make-or-break opportunity.

Exactly what demands they plan ro make, how-

ever, depends on whom you ask.

Tenants and Neighbors, a statewide tenant

advocacy group, recently kicked off Rent 2002,

a campaign that calls for extending the current

rent laws through 2006, in time for the next

governor's race, with one exception: Cut out

"vacancy decontrol."

In 1997, the last time it reauthorized the rent

laws, the New York State legislature let landlords

hike rent by 20 percent or more as tenants leave

regulated apartments. That measure has helped

landlords escape regulation entirely, thanks to

another provision included in the reauthoriza-

tion: Apartments renting for $2,000 or more are

now deregulated immediately upon vacancy.

Landlord rep Roberta Bernstein of the Small

Property Owners of New York says the rwo

provisions have "barely affected housing out-

side of midrown Manhattan." But Michael

McKee, associate direcror of Tenants and

Neighbors, tells a different srory. He says the

combination of provisions has led to the dereg-

ulation of2 percent of the city's rent-controlled

apartments berween 1997 and 1999.

Most tenant activists agree that getting rid

of vacancy decontrol is essential. But some are

still adamant about demands that the state leg-

islature ignored or repealed in 1997-demands

that are absent from the Tenants and Neigh-

bors' latest campaign.

"We could have a huge wish list," says Jenny

Laurie, executive direcror of the Metropolitan

Council on Housing. Topping their agenda, in

addition to rolling back decontrol: the repeal of

the Urstadt law, which allows the legislature to

determine the city's rent laws; reenacting a

stronger rent deposit law to give poor tenants

more than five days ro pay their back rent in

court; and extending fair-cause eviction laws ro

short-term tenants.

Met Council has not signed on ro the Rent

2002 campaign as of yet, and it is still figuring

our how it will handle its own organizing

efforts this year.

Meanwhile, McKee hopes his streamlined

agenda will soon draw more supporters. Dur-

ing Showdown 1997, he says, the tenants'

demands were roo scattered, and roo many. As

a result, he contends, their interests were com-

MARCH 2002

promised, and decontrol passed.

Not this time, he vows: McKee promises to

produce a bill lawmakers can't "duck and dodge."

As of mid-January, campaign members included

the Fifth Avenue Commirree, the Citywide Ten-

ants Coalition and the Nassau and Westchester

Tenant Coalitions. While Governor George

Pataki is their primary target, they are soliciting

support from Democratic gubernarorial candi-

dates State Comptroller H. Carl McCall, who was

the keynote speaker at Tenants and Neighbors

annual meeting this winter, and Andrew Cuomo.

"This bill isn't everything that tenants

want, " says McKee, "but Republicans will have

a hard time saying no. "

===TAXES

Give Them a Break

-Pat Sisson

GOVERNMENT FUNDING IS SCARCEST just when

it's needed most. That cruel recession irony is

prompting one advocacy group ro launch a

campaign that could add hundreds of millions

ro the pockets of low-income New Yorkers-

without costing the city a penny.

More than half a billion dollars in tax refunds

meant for poor working families go untouched

each year because as many as 200,000 city tax-

payers who are eligible for the Earned Income

Tax Credit (EITC) rebate fail ro fill out their tax

forms properly, or do not file at all.

Minding The Gap

FRONT llNES

According ro studies commissioned by the

Internal Revenue Service, berween 15 and 25

percent of taxpayers eligible for the federal-

and state-funded rebate do not receive their

payments. To qualifY, a family must earn less

than $32,121 a year, individuals less than

$10,710. The lower the income, the higher the

rebate: A family with rwo children that earns

$12,000, for example, receives the largest

credit, $4,008. On rop of that, New York State

offers its own tax credit rotaling 25 percent of

the federal refund.

However, many workers, particularly non-

English-speaking immigrants who fear deporta-

tion and former welfare recipients who are new

ro the job market, do not file their taxes at all.

"We're in such a financial crisis and there's this

big pile of money just sitting there," says Amy

Brown of the Community Food Resource Cen-

ter. To get that money ro the people who need it,

CFRC is offering free tax preparation at seven

locations including soup kitchens, credit unions,

union halls and the offices of neighborhood

groups. They're also running radio ads and a toll-

free information line in English (866-WAGE-

PLUS) and in Spanish (866-DOLARES) .

With a growing recession and tremendous

job loss since the September 11 attacks, there's

no doubt those rebates would help. Says Russell

Sykes, vice president with the Schuyler Center

for Analysis and Advocacy, which helped write

the state EITC bill: "That can single-handedly

jump that family over the poverty level. "

-Matt Pacenza

ONE DAY THREE YEARS AGO, NEARLY 100 social workers gathered to discuss welfare reform, a hot topic

for professionals serving low-income people. Their shared outrage about their clients' growing difficulties

with unyielding bureaucracies was tinged with concern about their own changing roles: focusing on short-

term troubleshooting rather than long-term assistance.

"There was an incredible amount of frustration and anger not just because clients were having a harder

time," remembers Mimi Abramovitz, a professor at the Hunter College School of Social Work, "but because

welfare reform had compromised our ability to delivery essential social services."

That concern inspired Abramovitz and the New York City chapter of the National Association of Social

Workers to survey the staff of 107 nonprofit human service agencies on the effects welfare reform has had

on their work. "In Jeopardy: The Impact of Welfare Reform on Non-Profit Agencies in New York City," funded

by the United Way, is scheduled for release in late February.

Whether employed in youth organizing, health care promotion, literacy education or mental health counsel-

ing, social service professionals across the city have all had to shift their missions since 1996. Their new focus:

helping clients fight for public assistance by battling sanctions, preparing defenses for appeals and arranging

for emergency food and housing. In the meantime, workers at 60 percent of the agencies surveyed say they are

"less able" to help with longer term problems like mental health and education.

For a copy of "In Jeopardy," call Yvette Moody of the United Way at 212-251-4112.

-Matt Pacenza

9

INSIDE TRACK

Hosed in Housing Court

Welfare families are supposed to get help with the rent.

Go tell that to the judge. By Nora McCarthy

Public assistance budgets just $312 for Anastasia Martinez' rent of $791 . Even when she faced eviction, caseworkers never told

her she qualified for more ai d.

WITHIN A WARREN of gray cubicles housing an

outpost of the Citizens Advice Bureau, Ener-

cida Matteo sits stiffiy, holding in her lap an

eviction notice torn from the door of her apart-

ment as marshals stacked her belongings in the

street. That was Thursday. Now she watches

the faces of the people speaking English around

her, looking for clues. (She speaks only Span-

ish.) Or she presses a hand to her face and cries

10

in silence. ''I'm scared," she says, "I don't want

to go to a shelter."

Matteo is one of the first clients at the evic-

tion prevention unit at a Bronx job center this

Monday morning, and at first glance, her case

makes no sense. Even with public assistance and

a job at a cosmetics factory, Matteo cannot afford

her full rent. As a welfare recipient on the verge

of eviction, she is entitled to a rent subsidy

known as Jiggetts. Named after the lead plaintiff

in a suit charging that New York's welfare rent

allowance of $286 a month for a family of three

is impossibly low, the subsidy, first ordered by a

state court in 1993, pays up to $650 for a house-

hold of that size. Citizens Advice Bureau receives

$1.3 million a year from the city to rue Jiggetts

applications in the Bronx.

When Matteo first came here in December,

CITY LIMITS

.

1

she'd already signed a stipulation in court

promising ro pay $4,000 in back rent by Janu-

ary 3. CAB filed her Jiggerrs application. The

state Office of Temporary and Disability Assis-

rance promised ro send a check and begin her

ongoing subsidy by that date.

But the process went awry. The check didn't

reach her landlord in time. When it failed ro

arrive, Marreo should have gone ro court ro

stay the eviction. (While a 1998 law bars judges

from granting tenants more time ro pay rent

once they've agreed in court ro pay by a certain

date, late checks from the state are cause for an

exception.) But, like 90 percent of tenants in

the Bronx, Matteo had no lawyer. She didn't

know about the loophole.

She got evicted. Now she and CAB have 10

days ro get the state ro come through with

$6,000 for back rent, legal fees and "moving

fees" incurred when the marshals dumped her

fumirure at the curb. In the end, the state paid

it-lining the landlord's pocket with $2,000

that could easily have been saved.

Few cases end well like Marreo's, but she is

like many in the ever-growing ranks of poor peo-

ple getting evicted-grasping at an inefficient

and inadequate rent subsidy, a flimsy protection

against homelessness. Only a few years ago, get-

ting Jiggetts was simple. But a major 1998

resuucruring of Housing CouC[ collided with an

overhaul of welfare, and for tenants on public

assistance, this has meant trouble. Housing

Court cases that once dragged on for months

now get resolved in weeks, giving tenants linle

time ro scrape rogether relief. At the same time,

as welfare rolls have dropped by half, Jiggetts par-

ticipation has fallen, [00. In 1998, 26,000 ten-

ants had their rent subsidized by Jiggetts. In

2000, JUSt 16,000 did.

The impact is obvious. In the Bronx, where

the proportion of the population on public

assistance is the highest in the city, the number

of evictions has shot up, from 5,575 in 1995 ro

8,119 in 2000. Brooklyn, roo, saw a dramatic

rise-from 5,350 in 1995 ro 7, 122 in 2000.

(In the rest of the city, rates have either

remained stable or declined.)

Many welfare recipients can no longer

count on Jiggens' protection. Stephanie Hall-

Wright and her 3-year-old daughter, Zariya,

who arrive at CAB's office wearing matching

Nikes, are one fanlily who may lose their home

ro this disjointed cataclysm of reforms. Wright,

who is 20 and on public assistance, owes about

$1,800 in renr. She seems baffled by her land-

lord's intention ro evict her.

"My landlord knew the situation was rough.

I was not working at the time and no one could

MARCH 2002

help, " she says, sounding angry and then fran-

tic. "I got a daughter. We can't be out on the

sueer. I need ro regroup, think of something

else ro do. This is stressful. "

But Wright's case, like many, will not be

easy ro resolve. She was sanctioned last summer

for not complying with a job training program.

Her welfare rent allowance-usually $250 a

month, far short of the $525 she pays her land-

lord-was reduced ro $93 a month. Even once

she gets Jiggetts, the subsidy will not cover back

rent that welfare cut off; Wright will have ro

repay that portion herself.

To get Jiggetts at all, she will have ro

straighten out her welfare case, which she does

not want ro do. ''They want you ro work in a

park for 75 cents an hour, " Wright says. "I don't

When they arrive

in Housing Court

now, landlords

have many new

opportunities to put

tenants on the fast

track to eviction.

have ro do this. I'm only 20. I can find a job. "

Of course, if her landlord doesn't want ro

wait, that choice may not be hers ro make.

ONLY A FEW YEARS ago, Jiggens represented a

sure shot for landlords. Most were eager ro coop-

erate with tenants ro get it. "I'd say that 85 per-

cent of the cases I deal with end in Jiggetts," land-

lord arromey Steven Goldstein [Old City Limits in

1998. "The point here is not [0 evict tenants. It

is [0 get our money and keep poor people in their

apartments. Jiggerrs does that. " With the subsidy,

landlords receive up ro $7,000 compensation for

back rent and the assurance that most of the rent

will continue ro be paid on time.

But during the late 1990s, owners in poor

neighborhoods starred demanding and getting

rent that exceeded what Jiggetts could pay. The

average rent for a two-bedroom in New York

INSIDE TRACK

City climbed past $834, according ro the

National Low Income Housing Coalition.

The 1997 state law overhauling rent stabi-

lization only gave owners more reasons ro pre-

fer eviction. That law allows landlords ro

increase rents on regulated apartments by 20

percent or more when they become vacant.

Landlords could find desperate tenants who

were willing ro pay high prices by living in large

groups. Other subsidies, such as Section 8, are

also more generous than Jiggetts.

Landlords can not only make more money

by kicking a tenant out, but recent Housing

Courr reforms also make it easier for them ro

get tenants evicted. Previously, a judge heard a

case while a tenant and landlord tried ro reach

a deal. If they couldn't compromise, that same

judge ran the trial. Now, because of the

restructuring, which was pushed by state Chief

Judge Judith Kaye, the court has been split

Into two parts.

One judge oversees a "resolution" part,

where both parties work toward a stipulation.

That states how much money a tenant will pay,

and by what date. Tenants might want ro refuse

a stipulation, because they know they can't get

the money [Ogether in the two weeks or a

month a landlord demands. Judges can pressure

a landlord ro be more flexible about the dead-

line, but there is nothing they can do besides

send the case ro trial-under a different judge.

But few tenants want ro go ro trial, where a

judge's decision is the fmal word. If a judge

decides [0 evict, tenants can be out of their

homes in as little as five days. Getting a trial date

used [0 take up ro six weeks; now it can happen

in just hours. Unprepared tenants often show up

at trial with no evidence ro sUppOrt their case.

Eviction also used ro stretch out over three

ro six weeks, but now the process takes only

days. To avoid going ro trial, tenants are likely

ro sign stipulations whose terms they know

they cannot meet, says Jodi Harawitz, direcror

of the City-Wide Task Force on Housing. They

hope that they can buy more time that way.

Usually, they can't. While requests for an exten-

sion rose ro about 190,000 in 2001 from

130,000 in 1995, the 1998 law drastically lim-

its judges' power ro grant tenants more time

once they sign a stipulation.

For landlords, the new regime is a good

thing: It means tenants have ro get the money

faster, or get out. Meryl Wenig, a Brooklyn

lawyer who often represents landlords, says the

law only makes sense. "If you've agreed ro pay by

a certain day, you shouldn't get several bites of

the apple," Wenig says. "If you couldn't make it,

don't sign it. You could have done a trial ."

11

Homesteaders Federal

Credit Union

120 Wall Street - 20th Floor, New York, NY

(212) 479-3340

A financial cooperative promoting home

ownership and economic opportunity since 1.987.

No-fee Personal and Business Checking Accounts

Savings, CD's, Holiday Club and Individual

Development Accounts. Personal, Small Business,

Home Equity, Mortgage and Co-op Loans

As a equal housing lender, we do business in accordance with

the Federal Fair Housing Law and the Equal Credit Opportunity

Act. Your savings are insured up to $100, 000 by the National

Credit Union Administration.

12

NANCY HARDY

Insurance Broker

Specializing in Community

Development Groups, HDFCs and

Non-Profits.

Low-Cost Insurance and Quality Service.

Over 20 Years of Experience.

270 North Avenue

New Rochelle, NY 10801

914-636-8455

Judge Fern Fisher-Brandveen, a Housing

Court administrator, believes the two-part sys-

tem has helped. "There are benefits on both

sides to making sure something is not dragged

our," she says. Still, she admits that the law pro-

hibiting judges from staying evictions may not

be an improvement: "In some cases the judge's

hands are tied, and maybe the law has made it

more difficult to extend the time in some cases

where time might be a good thing."

It's not impossible to rush a Jiggetts applica-

tion; advocates now have to do it all the time. It's

also possible to get an eviction delayed in some

cases. Legal Aid and Legal Services lawyers know

the loopholes. But their staffs have shrunk by

more than half in some boroughs over the last

decade, and very few tenants are represented.

Says Ed Josephson, director of the housing

law unit at Brooklyn Legal Services, "We see a

lot of people who are totally eligible for relief

money, but if we didn't step in and take the

case, they'd be out."

All OF THIS ASSUMES that tenants know they're

entitled to help. Many don't. One source of

obfuscation is the city's own Human Resources

Administration, which launched the Rental

Assistance Alert program in an effort to

decrease reliance on Jiggetts. RAA units help

welfare recipients wrangle money out of family

or charities, and workers don't recommend

Jiggetts until all other options have been

exhausted. "There are real problems with them

not referring cases quickly to the units who do

Jiggetts applications," says Susan Bahn, an

attorney with Legal Aid.

Welfare caseworkers also often fail to tell

tenants their rights. When a judge gave Anasta-

sia Martinez one month to pay $1,000 in back

rent, her caseworker never suggested a visit to

CAB. Martinez had received a Jiggetts subsidy

in 1998, but lost it during a brief sanction.

Jiggetts is not automatically reinstated when a

welfare case is reopened, and Martinez was

never told she could reapply. Instead, Martinez

got her sister to help out with the $791 rent.

Her sister lost her job after September 11, and

Martinez quickly fell behind.

Luckily, Martinez told a friend she might

get evicted, and the friend told her to contact

CAB. Now Martinez will have to ask a judge to

give her an extension while CAB tries to rush

the application.

Even if Jiggetts comes through, though, it

will not be enough. Martinez had to ask her

brother to pay the more than $150 difference

each month. "I have three kids," she says, "and

they gave me one month to get out. "

CITY LIMITS

STOP

HERE ON

RED

Classroom Adversaries

S

tudent protests at CUNY School of Law

shouldn't surprise anyone. After all, activism

has always been part of the curriculum at this

New York City institution. The school actually offers

a course in civil disobedience taught by professor

Dinesh Khosla, himself schooled first-hand in

demonstrations in India, where he was arrested more

than a dozen times for anti-government protests. His

first arrest for civil disobedience was at age 16, after

the Ford Foundation gave a grant to help his Delhi

high school adopt multiple-choice exams.

Still, it was something of a shock last April

when Khosla and a group of nine students went on

a hunger strike to protest the school 's handling of

faculty member Maivan Lam's tenure bid.

Lanl, acclaimed for her work on the rights of

indigenous people and a faculty member since 1992,

was also known for incorporating into her classes an

approach known as critical legal studies, along with

its controversial offshoots, critical race theory and

feminist jurisprudence. These doctrines look at legal

MARCH 2002

What are

activist attorneys

made of?

CUNY School of Law

is looking

to the bar exam

for answers.

By Wendy Davis

principles through the lens of injustices done to

women and minorities in the name of the law.

For example, when Lam taught her students

about a Supreme Court decision invalidating a law

banning mixed-race marriages, she also asked them

to think about the social pressures that originally

led to the law, as well as to consider who might have

benefited from it. Though the answer-white

men-may be obvious, the context of the law is

not. Lam posits that the ban on mixed-race mar-

riage served to protect fathers from the responsibil-

ity of supporting mixed-race offspring, and it insu-

lated white sons from estate challenges by mixed-

race half-siblings.

When Lam's tenure application was initially con-

sidered, the tenure committee recommended

approving it. Then the school's personnel and bud-

get committee asked CUNY Law's dean, Kristen

Booth Glen, to deny Lam tenure. In accordance

with the school's confidentiality policy, no reason

was ever given. (Court papers filed by Lam suggest

13

that the administration had qualms with her administrative duties and

her classroom teaching.

Lam's student supporters began protesting immediately after they

learned of the personnel committee's recommendation. They insisted that

the move had everything to do with other recent changes at the school-

particularly with curriculum initiatives aimed at making sure students

pass the bar exam. The students charged the school was forcing Lam out

her because her approach did not further the administration's goal.

They started a petition drive, garnering an estimated 150 signatures by

their count. When that didn't produce results quickly enough, they staged

a sit-in. Though the school agreed to add a student member to the per-

sonnel committee, relations between Lam's supporters and the adminis-

tration continued to deteriorate. As months went by without a final deci-

sion from the dean, the students suspected the administration was wait-

ing until the summer-when they would no longer be on campus-to

announce the result.

And so they resorted to the hunger strike, which ended on the fourth

day-after one student was taken to the hospital . Finally, several days

later, Dean Glen announced that the tenure denial would stand. Lam left

at the end of the semester and is now a visiting professor at American

University. (She also filed a lawsuit against CUNY,

Elsa Christiansen and Gordon

Kaupp j oined a hunger strike

supporting a radical professor's

tenure bid. Her absence, they say,

is a sign of CUNY's decline.

devoted to progressive causes, as

are most of Lam's other ardent

supporters. After graduating from

Skidmore College, Kaupp spent

three years in Colorado lobbying

to preserve affirmative action. He chose CUNY Law for its clinics in

international women's human rights and welfare rights advocacy, and

because the school's reputation led him to expect a liberal-leaning faculty

that approached all courses from "a very progressive angle."

For Kaupp and the other protesters, Lam was exactly the type of

teacher they anticipated working with at CUNY. "When we came here,

we expected every class would have critical theory, " says fellow hunger

striker Elsa Christiansen, a Brown University graduate who was drawn

to the school for its immigrants' rights clinic. "We believed each class

would be taught with the angle of repression. "

But there are other students who came to feel that there were times

when that kind of approach was itself oppressive. Nicole Al len, a second-

year student from Rochester who took a seminar with Lam last year,

thought Lam could be a harsh critic of students who did not agree with

her politics. "She was very opinionated about her views," says Allen,

adding that if students challenged Lam, she might dismiss them by say-

ing they were arguing a "very conservative" position.

Dean Glen declined to comment on the specifics of Lam's case, but

did volunteer that end-of-course evaluations included such vitriolic com-

ments as "the worst teacher I ever had."

At a school that prides itself on both diversity and

which is pending. In January, the EEOC deter-

mined a discrimination complaint could move for-

ward as well.) On the advice of her attorney, Lam

refused to comment for this story.

'This school used

a commitment to changing the world through law,

there are a lot of different views on what ought to go

into the education of public interest attorneys.

Lately, that tension has exploded into the open, and

into a virtual referendum on the future of one of

New York's great progressive institutions. Eighteen

years after its founding by a group of radical lawyers,

CUNY Law has found itself torn between two iden-

tities, building on its status as perhaps the most

activist law school in North America while facing

increasing pressure as a public university to provide

its graduates with the goods they'll need to succeed.

Now, nearly a year later, the students who ral-

lied behind Lam say they're still affected by the

turn of events. "Maivan really played a big role in

nurturing us intellectually and emotionally," says

Gordon Kaupp, a polite, earnest third-year student

who says he might have dropped out of school

were it not for Lam and her views on how racial

bias influences the law. "Maivan is fearless in chal-

lenging white privilege," he says. "I'm a white stu-

dent, and she would talk about race in a way that

wasn't always that comfortable for white students

to hear, myself included." Lam drew on history,

political science and sociology in her courses, and

encouraged students to deconstruct the laws they

were learning, not just memorize them.

Kaupp, who is preparing to move to California

and find a job representing low-income clients, is

14

to stand for

something.

Now, there's no

mission. It's run by

people who only

want to be managers.

This school has

lost its soul."

Professor Dinesh Khosla

Those demands aren't coming from students

alone. In 1997, after just 46 percent of CUNY

graduates passed the bar exam on their first try-

the current state average is 79 percent-the New

York Post editorialized in favor of shutting down

the school, and there was some fear that the

trustees might do just thar.

But these days, the loudest voices in Dean Glen's

ears come from right down the hall. "They're who [

CITY LIMITS

Dean Kristen Booth Glen

says that at her progressive

school, gender and race

studies don't need to be

segregated in special classes.

would have been, if I was a stu-

dent," she insists of her critics-in-

residence. That doesn't mean she

agrees wirh rhem. "It's like because

we want our students to pass rhis

bar, we're reactionary, horrible people, " she says, exasperated. "Politically,

we can't exist if our students don't pass rhe bar."

For all rhe hurdles facing rhe school, Glen, a former appellate court judge,

has done a remarkable job in helping raise rhe first-time bar-pass rate, while

also quelling any movement to shutter rhe school. Her initiatives have

ranged from inviting local politicians to observe classes to bringing in a con-

sultant to evaluate rhe way in which courses were taught and suggest changes

to improve rhe bar passage rate. The Community Legal Resource erwork,

anorher new project, provides technical assistance and orher resources to

graduates who launch neighborhood-based practices. Orher changes have

been more traditional: Students now receive letter grades instead of just pass-

ing or failing courses, and rhe worst performers now Aunk out.

But dissenting faculty members insist that Glen's ambitions for rhe

school have come at a cost. "When I came, we couldn't care less how we

were perceived by the mainstream legal community," laments Frank

Deale, a faculty member since 1989. "Now, the school is in a mindset of

mainstreaming . ... There is a concern we really need to up rhe ante in

terms of getting accepted by the traditional legal community. "

Khosla, who has butted heads many times wirh Glen, contends rhat the

new grading practices have created a "climate of fear. " He believes rhere's lit-

tle room in CUNY anymore for teaching rhat

1987 and served for seven years. He was still a member of rhe faculty in

1996 when he was killed in a car crash in Sourh Africa at rhe age of 55.

Under Burns' leadership, which coincided with a Democratic mayor

and governor, rhe school's reputation grew. Alrhough rhe American Bar

Association was nevet happy with the school's low first-time bar-passage

rate or its pass-fail grades, CUNY did become fully accredited.

Faculty who were on staff under Burns' leadership still speak long-

ingly of rhe popular dean's ability ro inspire people to work for social jus-

tice. "What drew me to the law school was rhat it was a place where stu-

dents would come because they really wanted to change society," says

Deale, who was a staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights

when he was first recruited to teach at CUNY in 1989.

Wirh rhe motto "Law in rhe Service of Human Needs," rhe law school

has an impressive track record of graduates who have dedicated rhemselves

to public service in New York City. Notable alumni include Housing

Court judges Pam Jackman-Brown, Margaret McGowan, and Schlomo

Hagler, City Council Member Larry Seabrook, and state Assembly Mem-

ber Jeffrey Klein. Anorher graduate, Miguel Negron, won the American

Bar Association's prestigious pro bono award last year for work on behalf

of immigrants and other low-income people.

CUNY graduates work in many of rhe institutions

emphasizes critical approaches to the law. "This

school used to stand for somerhing, " he says. "Now,

rhere's no mission. It's run by people who only want

to be managers. This school has lost its soul."

"It's like because

where rhe people of New York fmd rheir representa-

tion-at Legal Aid, rhe District Attorney's office, gov-

ernment agencies and in numerous small firms.

C

UNY Law was never anyone's idea of a typ-

icallaw school. It was founded in 1983 with

the purpose of training students to practice

public interest law-although from the begin-

ning, there was disagreement over rhe definition

of "public interest. " Some faculty felt that only

advocacy work directly on behalf of low-income

clients deserved that label.

But while rhe founders ultimately chose to also

train students for government work--even to be

criminal prosecutors-it was Haywood Burns,

who took over as dean in 1987, who came to

define rhe CUNY way of rhe law. Burns, a world-

famous activist who registered Sourhern black vot-

ers in rhe 1960s and was counsel to Martin Lurher

King J r. 's Poor People's Project, took over as dean in

MARCH 2002

we want our

students to

pass this bar,

we're reactionary,

horrible people.

Politically, we can't

exist if our students

don't pass the bar."

Dean Kristen Booth Glen

"I feel blessed to have gone to CUNY," says Edwina

Richardson Thomas, a fiercely loyal CUNY grad who

is now a referee in Queens Family Court. "There was

this true sense of commwlity. ... They put it into our

heads constantly: law in tile service of hwnan needs.

Whatever you do, use rhe law to help people."

Alrhough CUNY Law is classified by us. News

& World Report as a bottom quadrant, "fourth-tier"

law school, admissions are exceptionally competitive,

wirh only around one in rhree applicants accepted.

In part, rhe school draws so many applicants sim-

ply because it is affordable. New York state residents

pay tuition of only $5,700 a year; out-of-state resi-

dents, approximately $9,000. At Brooklyn Law

School and New York Law School, by comparison,

ruition is about $25,000 a year.

CUNY Law has also always attracted the best

and brightest from all over the country who could

15

have gone anywhere bur chose CUNY because of its progressive reputa-

tion and vaunted clinical programs, which are ranked fourth in the

country by Us. News. In the mandatory clinics, students represent

domestic violence victims, criminal defendants, immigrants and other

low-income clients. Clinical programs are now de rigueur at elite law

schools, but they weren't when CUNY started its programs; CUNY set

the example that they later followed.

The student body, although small at only around 150 per class, is in

no danger of being called monolithic, either in viewpoint or back-

ground. Glen says her vision for CUNY is for it to be a public interest

training ground as well as "the most diverse law school in the country."

This year, students of color made up an impressive 46 percent of the

entering class, a slight increase over last year.

The one thing all students are supposed to have in common is a com-

mitment to public interest law. About half of the class of 2000 ended up

in a public interest or public service job.

To help the admissions committee decide which

prospective students are truly committed to public

Under the administration of the

late Heywood Burns, CUNY law

gained a national reputation as an

activist Mecca.

"the revolutionaries. "

Second-year student Amy Wasserman entered CUNY with the goal of

becoming a criminal defense lawyer, but after taking one year of classes

she realized the work wasn't for her. Although active in the Public Inter-

est Lawyering Association, which raises scholarship money for students to

work at non profits, she now intends to work in real estate after gradua-

tion, for reasons she can't explain other than that she enjoys it.

Wasserman, a Rockland Counry native, did not get involved in last

year's protests, saying she didn't want to be distracted from her studies. "In

a lot of aspects you're consumed with law school," she says. "You try to dis-

regard anything that is not going to be beneficial to passing your finals. "

Located in a former junior high school in Flushing, CUNY Law is open

and unpretentious for a law school. There's on-site child care for students,

and yoga classes for the communiry. People here tend to be friendly, and to

pride themselves on it. Students' voices have long been heard here, largely

because the founders deliberately tried to do away with the hierarchical

institutional structure followed by other law schools, where the faculry

and administration wield near-absolute authoriry.

"When we started, we had as our goal a radical experiment in legal edu-

cation," says Victor Goode, a specialist in affirmative action cases and for-

mer executive director of the National Conference of Black Lawyers who

has been on the CUNY faculry since the beginning. "We thought we might

stand as a beacon of how things might be done differently."

From the start, however, there were political problems, with both the

larger CUNY administration and the American Bar Association. In 1986,

only 43 percent of the first graduating class passed the bar on their first

try, leading to embarrassing press attention. The

following year, the CUNY Chancellor fired rwo

interest work, applicants must write a personal essay

describing their aspirations and interests. Bur some

with more mainstream goals inevitably get in. Others

come to realize they have priorities other than work-

ing for a cause. Third-year student Hilda Quinto says

she wants to create her own financial securiry after she

graduates this May, as opposed to taking a low-pay-

ing public interest job. A 26-year-old Peruvian immi-

grant who settled in Florida at the age of 16, Quinto

now plans to do securities work for an investment

flrm-a career path that has been met with condem-

nation from some of her classmates.

Among the courses

no longer offered

are "Feminist

original faculry members, even though their col-

leagues had recommended them for tenure; a law-

suit soon followed.

Today, students still call professors by their first

names, although other early practices have faded

away. For instance, students and faculry no longer

meet in small groups, cal led "houses," to do a

postmortem on the week's courses.

"Some students have perspectives totally alien-

ated from what I think," says Quinto. "There was

division here since the fust day I arrived." She has

no patience for the hunger strikers, whom she calls

16

Jurisprudence, "

"Gender and the Law"

and "Critical Race

Studies. "

But more than any other single event, it was

the 1997 bar exam results that altered CUNY

Law's priorities. That July, only 46 percent of

CUNY grads passed the New York state bar the

first time they took it that year.

Whi le the bar passage rate had dipped low

before, the ciry was in a less forgiving mood in the

late 1990s. For one thing, the law school no longer

CITY LIMITS

Not every CUNY law student is

seeking a political education:

Amy Wasserman and Nicole Allen

both plan to go into real estate.

had the excuse that it was feeling its way through

uncharted territory. What's more, a gtowing para-

digm shift in higher education made standardized test scores a defining

measure of a school's success. With a Republican mayor and governor, and

with CUNY board members promoting performance standards for col-

leges, the school no longer had the luxury of downplaying bar exam results.

"With the Board of Trustees and the state legislature breathing down

your neck, you have to sacrifice," says Frank Deale, who is also an offi-

cer with the CUNY faculry union.

Pressure in the form of editorials by the ciry's tabloids, combined with

the perceived threat that the Board of Trustees might close the school,

left the administration desperate to boost its students' test success.

To that end, a host of changes were instituted. For one, the admissions

committee put an increased importance on the Law School Admissions Test

(LSAT), a multiple-choice exam designed to assess logical reasoning skills. A

student who scores high on the LSAT has a better chance oflater doing well

on the bar; like the LSAT, the bar exam is a timed, closed-book test. Now,

following a strict quota, the school admits no more than one-fourth of each

class with an LSAT below the 25th percentile. Just two people with a score

ranking below the 15th percentile have been admitted in the last two years.

At the time of the change, members of the administration knew they