Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

10 1 1 138 333

Загружено:

Navneet BaliИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

10 1 1 138 333

Загружено:

Navneet BaliАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2003, volume 21, pages 513 ^ 532

DOI:10.1068/d310t

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

Marieke de Goede

Politics, School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, England Received 14 December 2002; in revised form 17 April 2003

Abstract. In this paper I argue that the informal hawala money-transfer networks, which were made to take much of the blame for terrorist financing in the wake of the September 11 attacks, are not `underground' banking systems but are connected to Western banking in a myriad of ways. I argue that negative stereotyping of hawala in press and policy discourses has implicitly constructed Western banking as the normal and legitimate space of international finance and has deflected calls for regulation of Western investment banking. I discuss how hawala is connected to the financial exclusion of migrant workers in the West. In the war on terrorist finance, discourses of hawala have led to the underestimation of the complexity of cutting off terrorist funding, while criminalising remittance networks.

Introduction: September 11 and terrorist finance Not long after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001, hawala became identified in the news and in political discourse as an important channel through which the terrorists had been able to finance their acts. Hawala is a term for informal financial networks, originating from the Arabic root h-w-l which means `to change' or `to transform' (Passas, 1999, page 11). Hawala networks are believed to have originated in Asia centuries ago to provide safe money transfers for traders traveling along the Silk Route. The modern development of hawala is connected to the 1947 partition between India and Pakistan, when exchange controls made it illegal to transfer money between the countries and hawala filled the gap (Miller, 1999). Hawala networks arrange for the transfer of money domestically or internationally and may sometimes arrange credit.(1) Although there is much talk of the `underground' economy, or the `black market', hawala transactions are not illegal in most countries.(2) In principle, hawala transactions are not very different from international money transfers done by `normal' financial institutions, and hawaladars (hawala brokers) in Western cities do not operate underground but often openly

(1) Hawala is the term for financial networks which is commonly used in India; hundi is commonly used in Pakistan. Informal money-transfer networks of this kind have also developed in China (Fei ch'ien), Thailand (Phoe kuan), and Latin America (Casa de Cambio) (Passas, 1999, pages 9 ^ 12). Nikos Passas suggests that the term `informal value transfer system' is more accurate than hawala, alternative banking, or underground banking, which can all be found in Western policy and media discourses, because ``it is not always underground; banking is rarely involved, if ever; and it is not a single system'' (page 9). Although I agree with Passas on this, I have chosen to use the term hawala throughout this paper, because I am interested in discussing how discourses of hawala have influenced policy decisions in the wake of September 11. (2) India is a notable exception (Cottle, 2001). New address: Faculty of Humanities, University of Amsterdam, Herengracht 182, 1016 BR Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

514

M de Goede

advertise in the local press (Passas, 1999, page 20).(3) However, the defining aspect of informal money transfers is that they escape the formal accounting procedures of national governments and international institutions (Choucri, 1986, page 697). In contrast, money transfers done by international banks are formally recorded in the respective countries' balance of payment figures. In the wake of September 11, hawala became discussed in the international press as ``a banking system built for terrorism'' (Ganguly, 2001). One of the first articulations of this argument can be found in a September 26 article in the New York Times by William Wechsler, a former US Treasury official and director for Transnational Threats on the US National Security Council during the Clinton administration. ``It is wrong to think of al Qaeda as being financed primarily by Mr. bin Laden'', Wechsler (2001, page A19) wrote, ``More important is al Qaeda's global network of financial donors, Muslim charities, legal and illegal businesses, and underground money transfer businesses''. The image of a vast unregulated and underground money-transfer network at al Qaeda's disposal became widespread in news reports after the attacks. In Time magazine hawala was described as an ``international underground banking system that allows money to show up in the bank accounts or pockets of men like hijacker Mohammed Atta, without leaving any paper trail'' (Ganguly, 2001). Similarly, the Far Eastern Economic Review wrote that Asia's ``vast underground banking system'' was ``the likely channel bin Laden used to transfer his cash'' (Granitsas, 2001). Similar discourses of hawala can be found in government statements and policy documents. In the Hearing on Hawala and Underground Terrorist Financing Mechanisms before the US Senate in November 2001, Chairman Evan Bayh (2001) said in his opening statement: ``In this war against terrorism, one of the most critical battles will take place not in a foreign land, but in the financial world, as we seek to paralyze terrorist activities by cutting off the head of groups like al Qaeda. ... One system which bin Laden and his terrorist cells use to covertly move funds around the world is through `hawala', an ancient, informal, and widely unknown system for transferring money. _ Although most Americans have never heard of hawala, that system almost certainly helped al Qaeda terrorists move the money that financed their attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.'' When the Bush administration closed down a number of US-based hawaladars on November 7, 2001, President Bush stated: ``The entry points for these networks may be a small storefront operation. _ But follow the network to its centre, and you discover wealthy banks and sophisticated technology, all at the service of mass murderers. By shutting these networks down, we disrupt their murderous work'' (quoted in

(3)

Hawala works roughly as follows: if, for example, a migrant worker in the USA wants to send money to family in Pakistan, the worker can bring the money (for example, US $100) to a hawaladar in the USA. The US hawaladar (hawaladar A) will send a message (by telephone, fax, or e-mail) to his or her contact in Pakistan (hawaladar B). Hawaladar B then hands over the money (minus a commission) to the migrant worker's family (in Pakistan rupees), after the Pakistani family member has identified himself or herself (not necessarily through formal identification, such as a passport, but with the knowledge of, for instance, a code word). The transaction may be completed in as little as twenty-four hours. The hawaladars profit by charging a commission for the transfer. Hawaladar A will now owe the amount of the transfer to hawaladar B. This debt will be settled in the long term, but may remain outstanding for a while. Money transfers between the hawaladars in the opposite direction (for instance, by parents sending money to children studying abroad) may offset some of the debt. Eventually, the hawaladars may settle their debt through the underinvoicing or overinvoicing of shipped goods (that is, hawaladar A sends goods to hawaladar B, but charges US $100 less than the actual value of the shipment). The hawaladars may also settle their debts through international bank transfers, or by payments in cash or gold (Jost and Singh Sandhu, 2000).

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

515

Gordon and Powell, 2001). As a final example, a Harvard Law School paper on terrorist financing writes of hawala: ``These systems have generally survived to the present day _ because of the benefits they offer for illicit finance. _ Hawala systems have also been linked to narcotics, trafficking in human beings, terrorism, corruption, and smuggling'' (Gillespie, 2002, pages 8 ^ 9; compare also Thachuk, 2002). In press reports and political discourse, hawala became stereotyped as taking place in shabby, smoky, dark, and illegal places. For example, Michelle Cottle's search for hawala offices in Washington, which was published in both The New Republic magazine in the USA and The Guardian newspaper in the United Kingdom, opens with the following setting: ``The landing is dark, and the door to the officeostensibly a travel agencyis unmarked, save for a sticker proclaiming `I love Pakistan'. Outside on the street, small clusters of men lounge against cars and in doorways, calling out to passers-by. Inside, one rickety flight of steps up from Trina's Hair Gallery, the air is silent and stale. I obey a tiny sign, faintly visible in the gloom, instructing visitors to `ring bell'. Then I wait10, 20, 40 secondsuntil a pair of gold-rimmed glasses appears in a small, arched window above the door. I wave and smile. A lock clicks and the door opens several inches, dropping a thin streak of light onto the dingy green carpet. `I'm looking for the money transfer place ... ', I explain, my voice trailing off as a middle-aged Pakistani gentleman eyeballs me wearily'' (Cottle, 2001). The investigations of Time reporter Meenakshi Ganguly (2001) also took her to a ``smoked-filled ... office'', this time in the ``labyrinthine depths of old Delhi, where the lanes are too narrow for even a rickshaw [and] men drink tea and chat in shabby offices''. In the New York Times it is reported that, in a Kandahari bazaar, ``many hawala dealers are concentrated in a five-story concrete building that resembles a bunker, its interior dark and its offices lighted by dim bulbs'' (Frantz, 2001). I argue that stereotyping hawala as a dark and illegal space has implicitly constructed Western banking as the normal and legitimate space of international finance and has deflected calls for regulation of Western investment banking. Meanwhile, more than two years from the World Trade Centre attacks, a nuanced and integrated understanding of the meaning and functions of hawala within global financial networks is still lacking. In this paper, I take some first steps towards offering such an understanding. Rather than being a parallel system or an ``underground banking'' network (Miller, 1999), hawala is connected to the institutions and practices of Western banking in a myriad of ways. In particular, I discuss how hawala is connected to the financial exclusion of migrant workers in the West. In the war on terrorist finance, discourses of hawala have led to the underestimation of the complexity of cutting off terrorist funding, while criminalising remittance networks. In the first part of this paper, I examine the portrayal of hawala in the Western press and policy discourses and argue that an understanding of financial history demonstrates a close kinship between hawala and Western banking. In the second part I discuss hawala in relation to financial exclusion in the West, and critically examine Bush's financial-policy measures that followed the September 11 attacks. I conclude by discussing how the analysis offered here supports alternative policy measures to the ones taken in the war on terrorist finance. Hawala, trust, and financial history One of the main issues to be noted in the Western press and political discourses, which supposedly distinguishes hawala from Western finance, is the fact that hawala is based on trust and reputation, and leaves no records of its transactions. The image of international financing ``without leaving any paper trail'' (Ganguly, 2001) became

516

M de Goede

ubiquitous in reports on hawala. Hawala, it was noted in the Far Eastern Economic Review, is ``a system based on trustand cashthat leaves almost no paper trail. _ It's better than the modern banking system and it's untraceable'' (Granitsas, 2001). In December 2001 Kenneth Dam, Deputy Secretary of the US Treasury, wrote in the Financial Times that the international coalition against terrorism should pay attention to hawala in its efforts to ``[hunt] down dirty cash'', because ``terrorists move money through the hawala system, an ancient, trust-based way of moving money leaving virtually no trace'' (Dam, 2001). ``All that hawala requires is trust'', Time magazine wrote, ``and that, ironically, is why it thrives in the underworld'' (Ganguly, 2001). As one hawala broker told Ganguly in response to the question of whether hawala debts are ever denied or defaulted: ``No one cheats. ... The small gain would not be worth the bigger price. ... You will lose respect, and for a man, honour is his most important asset'' (Ganguly, 2001; compare also Behar, 2002; The Economist 2001). Leaving aside the question whether hawala is really paperlessCottle (2001), for example, notes the use of a `fat ledger' by the hawaladar she visits in Washingtonit can be debated whether the principles and practices of hawala are really that different from those of Western banking. Reliance on trust and reputation, which are now portrayed in the press as deviant aspects of informal and criminal finance, have always played an important part in Western banking itself. The etymological origins of the very concept of credit, on which Western banking is based, illustrate this point (de Goede, 2000, page 60). Credit, from the Latin credere, signifies belief, faith, and trusta person being worthy of trust, or having the reputation to be believed. Originally, as Craig Muldrew (1998, page 3) has documented, to be a creditor was possible as a function of social and moral standing: ``credit was extended between individual emotional agents, and it meant that you were willing to trust someone to pay you in the future _ . [T]o have credit in a community meant that you could be trusted to pay back your debts.'' Similarly, Nigel Thrift documents the historical importance of the ``narrative of the gentleman'' to London's financial district. This was one way in which the worth of people and practices was assessed: it was ``a widespread narrative based on values of honour, integrity, courtesy, and so on, and manifested in ideas of how to act, ways to talk [and] suitable clothing'' (1994, page 342). But it is not just early-modern credit which was generated through social and discursive networks of reputation and authority, to be progressively displaced by modern scientific methods of credit creation. Trust, reputation, and authority are at the heart of the operation of international finance today. Anthropologist Anna Hasselstrom (2000, page 261), for example, found in her interviews with financial traders and brokers in New York and London that they often use ``the concept of trust ... when reflecting over, explaining and analysing certain aspects of their daily lives''. Precisely because financial markets are ``characterised by a high multilevel degree of uncertainty'', Hasselstrom (page 268) argues, face-to-face interaction and personal contacts are of vital importance in creating trust between financial participants. The importance of trust and reputation in modern financial markets is further illustrated by David Bushnell, head of Global Risk Management at Citigroup, who testified before US Senate in July 2002 on the relations between Citigroup and Enron. ``While we regret our relationship with Enron'', Bushnell (2002, pages 3 ^ 5) said in his opening statement, ``we acted in good faith at all times. Our employees, including the bankers who are here today, are honest people doing honest business. _ We pride ourselves on our reputation for being an institution with integrity.'' Bushnell (page 4) went on to stress that all Citigroup's dealings with Enron had been evaluated and approved by the appropriate committees, which have the task of ensuring that Citigroup protects its ``reputation for high-quality financings and retain[s] investor confidence''. Bushnell's emphasis on the

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

517

honesty, integrity, and reputation of Citigroup illustrates how trust is not just an aspect of hawala and early-modern finance, but sits at the heart of global finance today.(4) Thus, some of the principles and practices of Western banking are not all that different from those of hawala. In fact, it can be argued that what hawala is vilified for (speed, trust, paperlessness, global reach, fluidity) are precisely the attributes that modern globalising investment banking aspires to. Bill Maurer (1999, page 375) discusses how, in the early 1970s, the use of paper shares in financial markets became seen as hampering market liquidity and as being ``too slow for contemporary capitalism''. Paper certificates were critiqued as being the ``Damocles sword hanging over the growth of our markets'', and the creation of a national stock-clearance system in 1976 promised to end the era in which ``flocks of messengers scurried through Wall Street clutching bags of checks and securities'' (quoted in Maurer, 1999, pages 377, 379). Paperless trading, then, is seen as key to the growth of contemporary financial markets, and as Philip Cerny (1997, page 157) points out: ``the expansion and globalisation of the financial services industry in recent years has been virtually synonymous with the rapid development of electronic computer and communications technology, which transfers money around the world with the tap of a key.'' By comparison, Citigroup's website advertises its Global Securities Services arm as ``a global leader in cross-border transaction services. _ With a leadership position in virtually every market served, Citibank Global Securities Services offers clients a full spectrum of custody, trust and safekeeping services'' (Citigroup, 2002a). Citigroup further advertises itself as ``an Economic Enterprise'' with ``a global orientation, but with deep local roots in every market where we operate'' (2002b). In short, then, hawala operates with a logic of paperlessness, speed, trust, and local knowledge that is highly valued in Western enterprise discourses (compare Weber, 2002, pages 142 ^ 146). Furthermore, the dividing line between `normal' financial institutions and hawala is not as clear-cut as many newspaper reports suggest. Terrorist financing relies upon a combination of financial channels, which includes regular accounts with major Western banks and money-transfer services. ``Al Qaeda has been able to move money around the world through ... [a] network of banks that ... have included France's Credit Lyonnais, Germany's Commerzbank, Standard Bank of South Africa and Saudi Holland bank in Jeddah in which ABN Amro of the Netherlands has a forty percent stake'', the Financial Times has reported (Willman, 2001). In addition, shortly after September 11 it emerged that the US-based money-transfer system Western Union Financial Services had been used for the transfer of terrorist funds, most notably when Atta made four money transfers to the United Arab Emirates, thought to be money left over from the preparations of the attacks (Business Week 2001). More generally, criminal financial activity within established international banks is on the increase, and can be considered, according to Lawrence Malkin and Yuval Elizur (2001, page 14), as ``the dark side of financial globalisation''. Malkin and Elizur document a number of recent cases in which the biggest Western banks such as Citigroup have been involved in money laundering and other fraudulent activities, including harbouring the money of corrupt Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha. They quote one former private banker who testified before the US Senate as saying: ``the private banking culture is essentially `don't ask, don't tell' '' exactly the kind of culture that the hawala network is being vilified for (Malkin and Elizur, 2001, page 15). Malkin and Elizur (pages 20 ^ 22) conclude: ``The United States ... has become the largest repository of ill-gotten gains in the world.'' Indeed, the construction of categories of harmful

(4)

Other sources documenting the importance of trust for the functioning of late-modern financial markets include: Boden (2000), de Goede (2003), Dodd (1994, pages ix ^ xxviii), and Thrift (2001).

518

M de Goede

financial activity in current money-laundering initiatives is highly politicised, according to Vincent Sica (2000). Western banks' willingness to receive flight capital from elites and corrupt regimes in Africa or Latin America, Sica argues, suggests that ``money laundering is a term of opprobrium to describe the movement of money to or from undesirable persons, organisations or countries'' (Michael Levi, quoted in Sica, 2000, pages 55 ^ 56; see also Naylor, 2002). The focus on hawala in the news and political discourse and the negative stereotyping of hawala networks, then, have had a dual effect in the wake of the September 11 attacks. First, the alignment between hawala and financial crime has provided an understanding of terrorist money as an `alien' problem. Although hawala offices are recognised to exist within the United States, they are seen as originating from and properly located within the black markets of Pakistan and the bazaars of Delhi, as some of the quotes above demonstrate. In the context of Bush's `war on terrorism', it is crucial that the enemy can be identified and isolated instead of being present within US institutions and practices in complex ways. As Patrick Jost (2001), a former official of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network of the US Treasury, testified before the US Senate: `` `hawala behaviour' lies well outside the cultural experience of most US investigators. Hawala is a system where large amounts of money are handed over without receipts, confirmation numbers, or identification. Hawala transactions take place in the context of a large network unlike a `traditional' corporate structure. The business of hawala is conducted informally, with little in the way of overhead and almost nothing in the way of regulatory infrastructure, making it, in this respect, nearly the antithesis of banking.'' The understanding of hawala as the antithesis of `normal' banking has created a financial enemy which is recognisable as `other', even if it is not always easily found or attacked. This discourse has facilitated drawing ``the lines of superiority/inferiority between us and them'' in the war on terrorist finance (Campbell, 2002, page 6). Second, the identification of hawala as a major and perhaps the main source of terrorist financing has served to deflect attention away from money-laundering practices within the big international financial institutions, and has in the long term been able to diminish the perceived urgency of the regulation of Western banking. The point here is not so much that policymakers have deliberately targeted hawala in order to distract from malfeasance in Western banks, but more subtly that the portrayal of hawala as an illegitimate and underground space implicitly produces Western banking as the legitimate and normal space. In the war on terrorist finance, hawala has become what Susan Bibler Coutin, Bill Maurer, and Barbara Yngvesson (2002, page 810) call the ``sovereign exception'', or the outside of global finance, which simultaneously produces its inside, or ``the very space in which the juridico-political order can have validity''. In other words, the underground, dark, and illegitimate sphere of hawala and the legitimate, lawful, and normal sphere of Western banking are mutually constituted.(5)

(5)

A similar argument has been made with regard to how offshore finance is imagined in debates on money laundering. Offshore, is not, as Ronen Palan (1998; 1999) has argued, a lawless area external to or far removed from the legal order of the sovereign state. Rather than existing as two distinct geographical spaces with clear boundaries, offshore and onshore are mutually constituted juridical constructs brought about by accounting procedures, and ``boundaries that exist are relative and fluid, defining a position of differentiation within the regulatory realm of the state'' (1999, page 21). The `fictitious space' of offshore simultaneously creates onshore as the normal, legitimate, and lawful space of global finance (Roberts, 1994).

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

519

I make this argument despite the fact that the Bush administration's response to the September 11 attacks included promises of quick and harsh actions against criminal activity within the global financial system. The Bush administration's financial response to the September 11 attacks was regarded as a ``sea change'' compared with its earlier positions on financial regulation. Prior to September 11, the Bush administration was reluctant to support new money-laundering laws, and did ``not want to pressure international banks in the United States and elsewhere to open their books'' (Weiner and Johnston, 2001). However, financial regulation has become a key component in the war on terrorism, and Thomas Biersteker (2002, page 83) notes a ``significant change of will'' on the issue of international financial regulation and anti-money-laundering legislation. On September 23, 2001, President Bush issued an Executive Order on Terrorist Financing, which was intended to ``starve terrorists of their support funds'' and which expanded the Treasury Department's power to ``target the support structure of terrorist organizations, freeze the US assets and block the US transactions of terrorists and those that support them'' (White House, 2001a). The order was accompanied by a list of names of individuals and organisations who were to be targeted internationally under the executive order. In addition, the USA Patriot Actpassed by Congress on October 24, 2001 included the International Counter-Money Laundering and Financial Terrorism Act. This act, amongst other measures, requires US financial institutions to terminate accounts with foreign shell banks in offshore financial centres, and requires all financial institutions to develop anti-money-laundering programmes (Dam, 2002, page 1). In April 2002, the US Treasury used the Patriot Act to extend reporting requirements to mutual funds, securities brokers, and commodities traders (Schepp, 2002). The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) the OECD organisation founded in 1989 to combat money laundering was given an expanded mission in October 2001, and became the main international organisation to combat terrorist financing. The FATF released eight special recommendations on terrorist financing, which included increased reporting requirements for financial institutions, but also the licensing of informal money-transfer networks and increased regulation of nonprofit organisations.(6) The financial response to September 11, it can be argued, provided a ``window of opportunity'' for those in favour of international financial regulation and anti-money-laundering efforts (Biersteker, 2002, page 83). However, one year on from the attacks the war on terrorist finance seemed to have progressed very little. The list of twenty-seven individuals and organisations released with Bush's executive order on terrorist financing in September 2001 has caused controversy. The reliability of the list has been questioned because many of the Arabic names were misspelled, and some of the persons on the list turned out to be dead. ``The spelling of names is a nightmare'', one banker is quoted in the Financial Times, ``there's no correct equivalent of Arabic names. Many of those listed [in the Executive Order] are very common names or noms de guerre'' (Peel and Willman, 2001). In addition, the FATF's eight special recommendations on terrorist financing are not yet implemented by most countries, including the USA and other G7 countries (The Economist 2002). Indeed, in September 2002 a report by the special UN monitoring group on al Qaeda concluded: ``No one should doubt that al Qaeda continues to have sufficient resources at its disposal to carry out its operations in many areas of the world and to plan and

(6)

The FATF's special recommendations on terrorist finance can be found at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/ SRecsTF en.htm.

520

M de Goede

launch further terrorist attacks. We cannot overstate the risks posed by al Qaeda, nor should we understate the complexity of the task remaining in cutting off its funding.'' (7) If a window of opportunity existed in the wake of September 11 for new international financial regulation in general and the closing down of tax havens in particular, the focus on hawala in media and political discourse has deflected such opportunities. Although legislative action in the wake of September 11 included tough new measures on all financial institutions, one of the few concrete actions taken by the US administration in its efforts to combat terrorist finance has been the closing down of the Somali-based hawaladar al-Barakaat. As I will discuss in the next section, the closing of al-Barakaat forced to the surface a number of issues concerning the politics of financial exclusion that provide an alternative understanding of hawala, which has been obscured by the reputation of hawala as a banking system `built for terrorism'. Hawala, financial exclusion, and remittances On November 7, 2001 the Bush administration blocked the assets of sixty-two organisations and individuals, including those of the Somali-based bank al-Barakaat.(8) At the time, President Bush stated: ``Today's action disrupts al Qaeda's communications, blocks an important source of funds, obtains valuable information, and sends a clear message to global financial institutions: You are with us, or with the terrorists. And if you are with the terrorists, you will face the consequences.'' According to the White House, al Barakaat was a financial network ``tied to al Qaeda and Usama bin Laden'', which ``raise[s] money for terror, invest[s] it for profit, launder[s] the proceeds of crime, and distribute[s] terrorist moneys around the world to purchase the tools of global terrorism.'' Al-Barakaat was further accused of ``provid[ing] terrorist supporters with internet service and secure telephone communications, and arrang[ing] for the shipment of weapons'' (White House, 2001b). Kenneth Dam of the US Treasury told a Senate hearing in January 2002 that ``Al-Barakaat is a Somali-based hawaladar operation, with locations in the United States and in 40 countries, that was used to finance and support terrorists around the world.'' Dam (2002) further boasted that: ``as part of that action, OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] was able to freeze [US]$1,900,000 domestically in Al-Barakaat-related funds on November 7, 2001. Treasury also worked closely with key officials in the Middle East to facilitate blocking of Al-Barakaat's assets at its financial centre of operations. Disruptions to Al-Barakaat's worldwide cash flows could be as high as [US]$300 to $400 million per year, according to our analysts. Of that, our experts and experts in other agencies estimate that [US]$15 to $20 million per year would have gone to terrorist organizations.'' The action on November 7 was accompanied by raids on Somali businesses in the USA, including a market in Southeast Seattle that housed Barakat Wire Transfer and money-transfer offices in Minneapolis, and the arrest of Mohamed Hussein,

(7) Quoted at http://www.un.org/av/ (page accessed in December 2002). The full text of the UN Security Council Report (S/2002/1050) can be found at: http://www.un.org/Docs/sc/committees/ 1267/1050E02.pdf. (8) Al-Barakaat illustrates the problematic dividing line between hawala and `normal' banking. Kenneth Dam of the US Treasury called the bank a hawaladar. Indeed, al-Barakaat seems to have flourished since the collapse of commercial banking in Somalia following the overthrow of the Siad Barre government in 1991, which led to large migratory movements of the Somali population. Al-Barakaat transfers money for the Somali diaspora according to the principles of hawala as explained in footnote 3. However, al-Barakaat was a large company and its activities included the provision of Internet and Islamic banking services in Somalia. It is thus not easy to say whether al-Barakaat was either a hawaladar or a bank, because it incorporated elements of both, and because the dividing line between the two is problematic in the first place.

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

521

a Somali-born Canadian citizen, who ran Barakaat North America (Davila, 2002; Hench, 2002). However, soon after the November 7 actions, international complaints against the closing of al-Barakaat were published. It transpired that al-Barakaat was the only bank, the largest employer, and the only Internet provider in war-torn Somalia. The bank offered international money transfers to the Somali diasporafor example, to Somali families living in the USA sending money to relatives in refugee camps. The actions against al-Barakaat ``made it harder for Somalis and other immigrants to send money to destitute family members in Africa'', one journalist noted (Hench, 2002). The day after the closure of al-Barakaat, Abdullahi Hussein Kahiyeh, general manager of the al-Barakaat group, denied having links with Osama bin Laden and told the BBC that he would welcome an ``open and transparent'' investigation into the activities of the group (BBC, 2001). The French magazine L'Express reported that the closure of al-Barakaat``the economic heart of Somalia''has reinforced anti-American sentiment with Somalia's population, who are still waiting to see the proof against the bank (Gylden, 2001). Aid agencies expressed worries that closing the bank ``could push the country, already reeling from civil war and famine, into the hands of extremists'' because ``remittances are the country's largest source of foreign exchange, estimated at [US]$500m a year, and dwarf foreign aid flows''. ``In the region we work'', Elkhidir Dahoum, Save the Children's Somalia programme manager told the Financial Times, ``50 percent of people are completely dependent on these funds'' (Turner and Alden, 2001). The US $1.9 million that Dam boasted to have seized included remittances frozen in transit, meaning that large amounts of capital never reached their destination. Al-Barakaat's closure ``greatly affected investment and labour opportunities in southern Somalia and crippled the construction and transportation sectors'', it was noted in an AfricaOnline article in April 2002. ``The humanitarian impact of the closure [of al-Barakaat] has been great'', this article concluded (Onyango, 2002). More generally, international remittances from migrants working in the West to their countries of origin represent important and underresearched international financial flows, through which the forms and functions of hawala are more properly understood.(9) Although information and statistics on international remittances are incomplete for obvious reasons, it is estimated that in many developing countries total remittances exceed the amounts and importance of international development aid. A recent World Bank report notes that ``remittance flows are the second largest source, behind [foreign direct investment] of external funding for developing countries'' and that ``remittances are ... more stable than private capital flows'' (World Bank, 2003, page 157). To give some examples, it is estimated that Latin America received US$18 billion from US residents in 2001 through wire-transfer companies, which are now under investigation as part of the war on terrorist finance. In several countries, including El Salvador and Nicaragua, remittances represent more than 10% of gross domestic product, and in Mexico the value of remittances exceeds both tourism and agriculture revenues (Hendricks, 2002). By comparison, an International Labour Organisation (ILO) study on remittances to Bangladesh found that in some rural areas of that country almost all families receive remittances, mainly from Saudi Arabia and Singapore, and that remittances constitute an average of 51% of the total income of these families (Siddiqui and Abrar, 2001, pages iii ^ iv). Another ILO study found that a large part of remittance income in recipient families is used for ``daily expenses such

(9) The term `remittances' is traditionally used to discuss international money transfers by migrant workers that are recorded in formal accounting procedures (Choucri, 1986). It is widely agreed, however, that the recorded flows are a fraction of actual money transfers, and here I use the term remittances to refer to both recorded and unrecorded money transfers.

522

M de Goede

as food, clothing and health care'', as well as for improving housing and buying land (Puri and Ritzema, 1999).(10) There has been little study of how exactly remittances reach their destination and what their relation is to global finance, but it is clear that hawala and other informal money-transfer networks are indispensable to remittance flows, in particular to Africa and Asia. The ILO study on Bangladesh found that 40% of remittances take place through hundi (compared with 46% through official banking channels). According to this study, the average costs of sending remittances through hundi or hawala is significantly lower than those of sending the money through Western banks or money-transfer companies such as Western Union. If we add the total transaction costs on the sending and receiving ends, sending money through hawala could half the costs (Siddiqi and Abrar, 2001, page v). The amounts of remittances by migrant workers are typically small, and the percentage taken by money-transfer services averages 13% (but can be up to 20%) of the amount transferred, whereas hawala dealers typically charge a commission of less than 5% (The Economist 2001, page 97; World Bank, 2003, page 165). However, it is important to note that costs are not the only, nor perhaps the most important, factor in the use of hawala by migrant workers. Migrant workers may be excluded from Western banking and `legitimate' money-transfer institutions for a complexity of reasons, including a lack of required paperwork in order to open a bank account (most importantly in the case of illegal immigrants), lack of language skills, lack of a formal education and the skills required to understand and fill out banking documents, and a distrust or fear of banks and other unfamiliar financial institutions (Al-Suhaimi, 2002, page 77). In Western countries in general, and in the USA in particular, opening a bank account is a complicated process which requires a number of official documents. In the USA, customers have to pay a fee in order to maintain a bank account, and account holders can be penalised for having bank balances below minimum requirements. In fact, financial exclusion of migrants has been exacerbated in the USA as a result of the Patriot Act, which requires additional identification of foreign nationals wishing to open bank accounts. John Herrara of the World Council of Credit Unions expressed concern before a Senate Hearing in February 2002 that the requirements of the Patriot Act result in ``many banks not welcoming immigrants'', who would be forced to ``head back to the usurious practices of money transfer companies, check cashers and payday lenders'' (2002, pages 2 ^ 3). Finally, it is important to note that the services offered by Western banks for international money transfers are wholly inadequate: they are costly, time-consuming, and not designed for small individual transactions. As the World Bank (2003, page 165) notes, banks have not shown much interest in workers' remittances in the past. Rahim Bariek, a US hawala broker originally from Afghanistan, told the US Senate during a Hearing on Hawala of the difficulty of sending money to Pakistan through `legitimate' channels: ``In 1997, I wanted to send money to my father-in-law in Pakistan. I went to my local branch of Chevy Chase Bank to wire the money. The bank told me that there was no way that they could guarantee a money transfer to Pakistan, because there is a great deal of corruption in the formal banking system in Pakistan and money often disappears. I tried to send a money order, but it was stolen from the mail. The only

The development literature has centred around the question of whether remittances (and labour migration in general) have a positive long-term impact on remittance-receiving families and (local) economies and whether they contribute to development (for this discussion see, for example, Adams, 1998; Ahmed, 2000; Arnold, 1992; Griffith, 1985; Jones, 1998; Martin and Straubhaar, 2002; Puri and Ritzema, 1999).

(10)

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

523

way that I could get the money to my father-in-law in Pakistan was through a hawala. It was safe, faster and cost less'' (Bariek, 2001). The rural areas in, for example, Afghanistan and Pakistan from which migrant workers originate are often not connected to Western banking networks. In the Muslim world, a professor at Georgetown University testified before the same Senate hearings, ``cash remains the preferred medium for settling transactions. _ Banking institutions are concentrated in urban centres and cater mainly to the needs of governments and elite segments of society'' (Yousef, 2001). In addition, an International Monetary Fund (IMF) assessment of hawala points to the gender dynamics at work in some migrant workers' use of hawala, as hawaladars ``known in the village and aware of the social codes'' would make it possible for women receiving remittances to avoid dealing directly with banks (El-Qorchi, 2002, page 33). These are reasons why the often used term `alternative' banking systems is inappropriate, according to Nikos Passas, an expert in white-collar crime at Temple University who undertook a study of remittance networks for the Dutch Ministry of Justice. ``The reasons why I am reluctant to use _ the word `alternative' '', Passas writes (1999, page 11), ``are that some of these systems predate the conventional banking systems and because in many parts of the world these `alternatives' are actually the rule the formal banking system is the exception, the `alternative' system''. In fact, the United Nations, the European Union, and international aid agencies have at times used hawala networks, including al-Barakaat, in order to transfer money to (rural) areas where Western banks are absent (Karimi, 2002; Turner and Alden, 2001). Under these circumstances, hawala and other informal money-transfer networks offer services that are fast, cheap, and reliable compared with other possibilities. Although hawala and other money-transfer networks may sometimes be used for criminal purposes, including the laundering of drug profits, Passas (1999, page 67) found that their criminal use has been exaggerated in press and policy documents, and that they do not ``represent a money laundering or crime threat in ways different from conventional banking or other legitimate institutions''. Passas (1999, page 4) warns that criminal law appears to be the ``least effective way of dealing with'' informal money-transfer networks, that measures against these networks ``may give the impression that the cultural traditions underpinning [them] are unfairly attacked'', and that extending money-laundering legislation to remittance networks would needlessly criminalise their clients. It certainly seems to be the case that the actions against al-Barakaat needlessly criminalised Somali immigrants in the USA, while proof of al-Barakaat's links with al Qaeda remains tenuous. In April 2002 an unidentified senior US official was quoted in the New York Times as saying of the closure of al-Barakaat: ``This is not normally the way we would have done things. _ We needed to make a splash. We needed to designate now and sort it out later'' (Golden, 2002, page A10). The same New York Times article goes on to report that the evidence against al-Barakaat hinged on its connection to the Somali Islamist movement al Itihaad, which ``emerged from the widespread Somali opposition to Muhammad Siad Barre, the American-backed dictator who fell in 1991'' (page A10). Al-Barakaat's precise connections to al-Itihaad remain, however, unspecified, and al-Barakaat's founder denies supporting the Somali movement. In fact, Tim Golden (2002) goes on to report, the most concrete evidence available against al-Barakaat at the time of its closure on November 7 was provided by the US Customs Service, which had uncovered ``several instances in which Somali immigrants who were involved in welfare fraud or drug-dealing had used the company to send money home''. In February 2002 GroenLinks, the Dutch Green Party coalition partner at the time put questions to the Dutch Parliament on the basis of

524

M de Goede

a visit to Somalia. The Green Party argued that the Somali population had become the victim of the sanctions against al-Barakaat, demanded to know whether the Dutch government had seen evidence against al-Barakaat, and argued that the Somali people have the right to see this evidence, given the importance of the bank for the Somali economy and society (Karimi, 2002). Moreover, the evidence against the Somalis targeted in the November 7 operation in the USA and elsewhere has been questioned. In July 2002 Mohamed Hussein, arrested in the November 7 raids, was found guilty of running an unlicensed hawala and was sentenced to one and a half years in prison and two years of supervised release (US Treasury, 2002, page 38). Hussein was convicted because his money-transfer business did not have a licence in Massachusetts where it operated, and no mention of terrorism or terrorist financing was made in his indictment. Hussein's conviction is, so far, one of the few under the Patriot Act, which specifically provides that no proof was required that Hussein even knew of the licensing requirement (US Treasury, 2002, page 9). Meanwhile, a Canadian judge has refused to extradite Hussein's brother Liban, and the Canadian Foreign Ministry stated that ``Canada has concluded that there are no reasonable grounds to believe Mr. Hussein is connected to any terrorist activity'' (quoted in Cassel, 2002). Further, the US government has been forced to drop the charges against Garad Jama, a US citizen of Somali descent, who was accused of having terrorist connections because he ran the Aaran money-transfer business in Minneapolis (Tapper, 2002). Jama's business was raided as part of the November 7 operation, his assets were seized, and his name was associated with terrorism on the news. However, in August 2002 the US government admitted it had no evidence against Jama and requested the removal of Jama's name and that of six other individuals and businesses from the UN sanctions list of alleged terrorists (Nelson, 2002). But, at the time of writing this paper, Jama's name could still be found on the website of the US Treasury and OFAC in connection with terrorism and money laundering.(11) Finally, Sweden has dropped proceedings against three Somali-born Swedish citizens whose assets were frozen and whose names were placed on the UN terrorism list because they run al-Barakaat Sweden. The Swedish government was initially reluctant to listen to the Somalis' claims of innocence, but the case generated widespread publicity in Sweden and, as the New York Times reported, ``prominent Swedes defied sanctions regulations by taking up a collection for their legal fees'' (Schmemann, 2002). It has further been reported that the US Treasury sent the Swedish government a list of twenty-seven pages to prove the case against the men. However, of these, ``twenty-three pages were news-release material; a packet of background documents on al Barakaat, including a statement by President Bush on al Qaeda'' (Cooper, 2002). The Swedish government's requests for further proof from the US Treasury remained unanswered, and the Swedish authorities declined to press criminal charges against the men. In August 2002 the men's names were finally removed from the UN sanctions list.(12) In the war on terrorist finance, the migrant workers who have suffered from the closing down of al-Barakaat and the scrutiny of other money-transfer networks are considered ``collateral damage'' by the US Treasury (Scott-Joynt, 2002). The US government has acknowledged the important functions of the hawala networks, and hearings held before the US Senate in November 2001 saw testimonies which emphasised the

See the US Treasury's site at http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac/actions/20020827.html, and OFAC's site at: http://www.sia.com/moneyLaundering/html/ofac fincen.html (page accessed on December 2002). (12) The UN press release (dated August 26, 2002) removing the Swedish suspects and Garad Jama from the UN sanctions list can be found at: http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2002/sc7490.doc.htm.

(11)

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

525

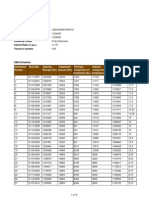

Figure 1. Poster from the US Treasury Terrorist Financing Rewards Program (http://www.ustreas.gov/rewards).

526

M de Goede

Figure 2. Poster from the US Treasury Terrorist Financing Rewards Program (http://www.ustreas.gov/ rewards).

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

527

social and economic functions of hawala for migrant communities.(13) However, the crackdown on informal money-transfer networks as a result of September 11 has made it more difficult and more costly for migrant workers to remit money, and has left migrant workers looking for formal banking channels to remit funds (World Bank, 2003, pages 165 ^ 172). Hawala networks have been generally criminalised, as illustrated by the recent Terrorist Financing Rewards Program launched by the US Treasury, which mobilises the public to help stop terrorist financing. Under the banner ``Stopping Terrorism Starts with Stopping the Money'', the treasury information poster lists ``alternative remittance systems'' under the heading ``Illicit Sources'', along with drug smuggling, identity theft, fraud, and counterfeiting (figure 1). Another poster in the same campaign shows a picture of Bin Laden, pictures of the destroyed World Trade Centre and a picture of cash of different denominations (but no US dollars) under the banner ``Stop the Flow of Blood Money!'' (figure 2). Finally, more than one year on from the start of the war on terrorist finance, al-Barakaat has been virtually destroyed. Although some of the organisation's North American assets have been released in August 2002, 90% of the bank's assets are in the United Arab Emirates and are still frozen, and in November 2002 the Transitional National Government of Somalia called for the removal of the freeze during peace talks in Kenya (BBC, 2002). Rob Nichols, Deputy Assistant Secretary at the US Treasury, acknowledges that the closing of informal money-transfer networks such as al-Barakaat is ``causing much grief''. Nichols calls these effects of the war on terrorist finance regrettable but necessary, and told the BBC: ``It may require folks to find alternatives, but we simply cannot allow a pipeline to al Qaeda to exist'' (quoted in Scott-Joynt, 2002). Conclusions David Campbell has argued that the war on terrorism relies on a structure of understanding enmity and security which bears striking resemblance to the understanding of good and evil in the Cold War era. ``[T]his structure means'', Campbell (2002, page 6) writes, ``that abuses and atrocities equal to or greater than the original crime that put us on this new path will be overlooked and tolerated, so long as the strategic goal remains in focus. _ Struggles unrelated to the global threat will nonetheless be cast as compradors of international terrorism, repressive policies will not be questioned, and those that dare criticise this complicity will be labelled fellow travellers of the terrorists.'' In the USA and its allied countries, Campbell (page 7) argues further, most of the measures taken in response to the September 11 attacks ``are directed against foreign others''. In this paper I have argued that the representation of hawala as a foreign, dark, and illegal system at al Qaeda's disposal has helped to draw the lines between good and bad in the war on terrorist finance. Hawala as a discourse of financial deviance has legitimised repressive policies, including the targeting of Somali money-transfer businesses

(13)

Acknowledgments of the important functions of hawala with respect to migrants' remittances can also be found, for example, in a report detailing treasury action with respect to the Patriot Act (US Treasury, 2002). This report argues that US action with respect to hawala is consistent with the Abu Dhabi declaration, which was drawn up during an international conference on hawala organised by the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates in May 2002, attended by government officials, central bankers, and representatives of the IMF and the United Nations. The Abu Dhabi declaration recognised the need for a better understanding of hawala and emphasised its positive aspects, while recommending its regulation (http://www.cbuae.gov.ae/Hawala/Hawala1Presentations.htm, accessed May 30, 2002). Nevertheless, the US Treasury report criminalises hawala and details cases where unlicensed remittance brokers have been investigated and prosecuted.

528

M de Goede

in the USA and Sweden and the disruption of remittances to one of the poorest countries in the world. It has to be made clear that I do not argue that al-Barakaat and other informal money-transfer businesses are never used for criminal purposes, including money transfers by (potential) terrorists. However, it has been proven that al Qaeda's members have made use of both Western Union money-transfer services and of ordinary checking accounts in US banks. In this context, the raids on Somali individuals and businesses illustrate how measures taken in the wake of September 11 target foreign others, while measures against Western financial institutions that allow money laundering, tax evasion, and financial exclusion of migrant communities remain weak. Indeed, it can be argued that the best way to undermine hawala networks is to legally require mainstream banks to offer accessible and cheap money-transfer services and other financial products to migrant-worker communities. For example, in response to evidence of money laundering through hawala networks in Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency ``has encouraged Saudi banks to meet the challenge of creating fast, efficient, quality and cost-effective fund transfer systems _ that cater to the special needs of the expatriate workers'' (Al-Suhaimi, 2002, page 78). In the USA and the United Kingdom, however, the big international banks such as Citibank and Barclays are decreasingly welcoming low-income clients, and are concentrating their product development on clients with substantial resources to save and invest (Leyshon and Thrift, 1997, pages 225 ^ 259). In contrast, the credit unions and the ILO have recognised remittances as an important political issue, and are encouraging the development of cheap and efficient international money-transfer networks. The World Council of Credit Unions (WOCCU) is developing a remittance network which provides cheap and reliable money-transfer services to its members.(14) This network, called IRnet, operates between US credit unions and forty other countries, and allows migrant workers to send, for example, US$1000 to Mexico for a fee of US $10 much lower than fees charged by most money-transfer businesses. However, the development of IRnet and other WOCCU initiatives receive little governmental support, and John Herrara (2002, page 4) of WOCCU pleaded with the House Committee on Financial Services for regulatory changes, including permission for credit unions to serve nonmembers. In the war on terrorist finance, the US government has tried to provide a particular kind of security which has relied on the identification of hawala as the problem. ``[B]ecause security is engendered by fear'', Michael Dillon (1996, pages 120 ^ 121) writes, ``it must also teach us what to fear when the secure is being pursued ... . Hence, while it teaches us what we are threatened by, it also seeks in its turn to proscribe, sanction, punish, overcome that is to say, in its turn endanger that which it says threatens us.'' Discourses of hawala teach that what we are threatened by, in a financial sense, is a dark and criminal underworld of hawala networks, which must be expelled from US society. However, this discourse has led to the underestimation of the complexity of the task of paralysing terrorist financial networks. Because it relies on a simplistic distinction between `us' and `them' between normal finance and the deviance of hawala the war on terrorist finance fails to recognise the multiple and complex ways in which Western banking lends itself to criminal activity. Meanwhile, remittance networks are needlessly criminalised, and initiatives which tackle the financial exclusion of migrant communities fail to receive the necessary policy support.

(14) http://www.woccu.org/prod serv/irnet/; for remittances and the ILO see: http://www.ilo.org/public/ english/employment/finance/remit.htm.

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

529

Acknowledgements. This research was financially supported by an ESRC postdoctoral fellowship. The paper has much benefited from comments by: Louise Amoore, David Campbell, David George, Gunther Irmer, Tim Kelsall, Paul Langley, Bill Maurer, Erna Rijsdijk, Tim Sinclair, Eleni Tsingou, and an anonymous referee for Environment and Planning D. References Adams R H, 1998, ``Remittances, investment and rural asset accumulation in Pakistan'' Economic Development and Cultural Change 47(1) 155 ^ 173 Ahmed I I, 2000, ``Remittances and their economic impact in post-war Somaliland'' Disasters 24 380 ^ 389 Al-Suhaimi J, 2002, ``Demystifying hawala business'' The Banker 152(914) 76 ^ 78 Arnold F, 1992, ``The contribution of remittances to economic and social development'', in International Migration Systems Eds M M Kritz, L L Lim, H Zlotnik (Clarendon Press, Oxford) pp 205 ^ 220 Bariek R, 2001, ``Prepared statement of Mr. Rahim Bariek'', Hearing on Hawala and Underground Terrorist Financing Mechanisms, US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 14 November, http://banking.senate.gov/01 11hrg/111401/bariek.htm Bayh E, 2001, ``Opening statement of subcommittee Chairman Evan Bayh (D-IN)'', Hearing on Hawala and Underground Terrorist Financing Mechanisms, US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 14 November, http://banking.senate.gov/01 11hrg/ 111401/bayh.htm BBC, 2001, ``Somali company `not terrorist' '' BBC News Online 8 November, http://news.bbc.co.uk/ 1/hi/world/africa/1645073.stm BBC, 2002, ``Somali factions want bank assets freed'' BBC News Online 11 November, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/2442685.stm Behar R, 2002, ``Kidnapped nation: welcome to Pakistan, America's frontline ally in the war on terror'' Fortune 29 April, page 84 Biersteker T J, 2002, ``Targeting terrorist finances: the new challenges of financial market globalisation'', in Worlds in Collision: Terror and the Future of Global Order Eds K Booth, T Dunne (Palgrave, Basingstoke, Hants) pp 74 ^ 84 Boden D, 2000, ``Worlds in action: information, instantaneity and global futures trading'', in The Risk Society and Beyond: Critical Issues for Social Theory Eds B Adam, U Beck, J van Loon (Sage, London) pp 183 ^ 197 Bushnell D, 2002, ``Opening statement of David Bushnell'', Hearing on The Role of the Financial Institutions in Enron's Collapse, US Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, 23 July, http://www.senate.gov/$gov affairs/072302bushnell.pdf Business Week 2001, ``Western Union: where the money isin small bills'', 26 November, pages 40 ^ 41 Campbell D, 2002, ``Time is broken: the return of the past in the response to September 11'' Theory and Event 5(4), http://www.tnr.com/101501/cottle101501.html Cassel D, 2002,``US counter-terrorism: leap before you look?'' World View Commentary number 136, Center for International Human Rights, Northwestern University, Chicago, 6 June, http://www.law.northwestern.edu/depts/clinic/ihr/display details.cfm?ID=326&document type =commentary Cerny P, 1997, ``The search for a paperless world: technology, financial globalisation and policy response'', in Technology, Culture and Competitiveness: Change and the World Economy Eds M Talalay, C Farrands, R Tooze (Routledge, London) pp 153 ^ 166 Choucri N, 1986, ``The hidden economy: a new view of remittances in the Arab World'' World Development 14 697 ^ 712 Citigroup, 2002a, ``How Citigroup is organised'', Citigroup website, http://www.citigroup.com/ citigroup/about/index.htm Citigroup, 2002b, ``Our values add value'', Citigroup website, http://www.citigroup.com/citigroup/ corporate/values/index.htm Cooper C, 2002, ``UN sanctions ensnare individuals, not just countries'' Arizona Daily Star 6 May, http://www.azstarnet.com/attack/indepth/wsj-unsanctions.html Cottle M, 2001, ``Hawala v. the war on terrorism: Eastern Union'' The New Republic 15 October, http://www.tnr.com/101501/cottle101501.html, accessed May 2002 Coutin S B, Maurer B, Yngvesson B, 2002, ``In the mirror: the legitimation work of globalization'' Law and Social Inquiry 27 801 ^ 843

530

M de Goede

Dam K W, 2001, ``Hunting down dirty cash: the international coalition must step up its efforts to stem the flow of terrorist funds or risk further attack'' Financial Times 12 December Dam K W, 2002, ``Prepared statement of the Honorable Kenneth W. Dam'', Hearing on The Financial War on Terrorism and the Administration's Implementation of the Anti-Money Laundering Provisions of the USA Patriot Act, US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 29 January, http://banking.senate.gov/02 01hrg/012902/dam.htm Davila F, 2002, ``Raid on Iraqi-owned market here prompts nationwide crackdown'' Seattle Times 21 February, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/134408460 raid21m0.html de Goede M, 2000, ``Mastering lady credit: discourses of financial crisis in historical perspective'' International Feminist Journal of Politics 2(1) 58 ^ 81 de Goede M, 2003,``Beyond economism in international political economy'' Review of International Studies 29(1) 79 ^ 97 Dillon M,1996 Politics of Security:Towards a Political Philosophy of Continental Thought (Routledge, London) Dodd N, 1994 The Sociology of Money: Economics, Reason and Contemporary Society (Continuum, New York) El-Qorchi M, 2002, ``Hawala'' Finance & Development 39(4) 31 ^ 33 Frantz D, 2001, ``A nation challenged: the financing; ancient secret system moves money globally'' New York Times 3 October, page B5 Ganguly M, 2001, ``A banking system built for terrorism'' Time 5 October, http://www.time.com/ time/world/article/0,8599,178227,00.html Gillespie J, 2002 Follow the Money: Tracing Terrorist Assets Seminar on International Finance, Harvard Law School, 15 April, http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/PIFS/pdfs/james gillespie.pdf Golden T, 2002, ``A nation challenged: money; 5 months after sanctions against Somali company, scant proof of Qaeda tie'' New York Times 13 April, page 10 Gordon G, Powell J, 2001, ``Terror probe turns to Minneapolis'' Star Tribune 8 November, http://www.startribune.com/stories/843/813232.html Granitsas A, 2001, ``Osama Bin Laden: the cash flow'' Far Eastern Economic Review 4 October, http://www.feer.com/2001/0110 04/p28region.html, accessed 10 October 2001 Griffith D C, 1985, ``Women, remittances and reproduction'' American Ethnologist 12 676 ^ 690 Gylden A, 2001, ``La Somalie a la derive'' [Somalia astray] L'Express 6 December, http://www.lexpress.fr/Express/Info/Monde/Dossier/somalie/dossier.asp Hasselstrom A, 2000, `` `Can't buy me love': negotiating ideas of trust, business and friendship in financial markets'', in konomie und Gesellschaft Jahrbuch 16: Facts and Figures: Economic Representations and Practices Eds H Kalthoff, R Rottenburg, H-J Wagener (Metropolis Verlag, Marburg) pp 257 ^ 275 Hench D, 2002, ``Man guilty of running unlicensed `hawala' '' Portland Press Herald 1 May, page 1A Hendricks T, 2002, ``Wiring cash costly for immigrants: money transfer firms bite into funds sent home to families'' San Francisco Chronicle 24 March, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2002/03/24/MN55527.DTL Herrara J A, 2002, ``Testimony of John A Herrera'', Hearing Entitled The Patriot Act Oversight: Investigating Patterns of Terrorist Financing, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, 12 February, http://financialservices.house.gov/ media/pdf/021202jh.pdf Jones R C, 1998, ``Remittances and inequality: a question of migration stage and geographic scale'' Economic Geography 74(1) 8 ^ 25 Jost P, 2001, ``Prepared statement of Mr. Patrick Jost'', Hearing on Hawala and Underground Terrorist Financing Mechanisms, US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 14 November, http://banking.senate.gov/01 11hrg/111401/jost.htm Jost P, Singh Sandhu H, 2000 The Hawala Alternative Remittance System and Its Role in Money Laundering Interpol General Secretariat, January, http://www.interpol.int/Public/FinancialCrime/ MoneyLaundering/hawala/default.asp Karimi F, 2002, ``Actie voor Somalie dringend nodig'' [Action for Somalia urgently necessary] Groen Links 26 February, http://www.groenlinks.nl/partij/2dekamer/nieuws/4001066.html Leyshon A, Thrift N, 1997 Money/Space: Geographies of Monetary Transformation (Routledge, London) Malkin L, Elizur Y, 2001, ``The dilemma of dirty money'' World Policy Journal Spring, 13 ^ 23 Martin P, Straubhaar T, 2002, ``Best practices to reduce migration pressures'' International Migration 40(3) 5 ^ 23

Hawala discourses and the war on terrorist finance

531

Maurer, B, 1999, ``Forget Locke? From proprietor to risk-bearer in new logics of finance'' Public Culture 11 365 ^ 385 Miller M, 1999, ``Underground banking'' Institutional Investor 33(1) 102f Muldrew C, 1998 The Economy of Obligation: The Culture of Credit and Social Relations in Early Modern England (Macmillan, London) Naylor R T, 2002 Wages of Crime: Black Markets, Illegal Finance and the Underworld Economy (Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY) Nelson T, 2002, ``Somali awaits clearing of name'' Pioneer Press 23 August, http://www.twincities.com/ mld/pioneerpress/3919263.htm Onyango D, 2002, ``UN moves to save al Barakaat'' AfricaOnline.com 29 April, http://www.africaonline.com/site/Articles/1,3,47323.jsp Palan R, 1998, ``Trying to have your cake and eating it: how and why the state system has created offshore'' International Studies Quarterly 42 625 ^ 644 Palan R, 1999, ``Offshore and the structural enablement of sovereignty'', in Offshore Finance Centres and Tax Havens:The Rise of Global Capital Eds M P Hampton, J PAbbott (Macmillan, London) pp 18 ^ 42 Passas N, 1999 Informal Value Transfer Systems and Criminal Organisations: A Study into So-called Underground Banking Networks Dutch Ministry of Justice, http://www.minjust.nl:8080/b_organ/ wodc/publications/ivts.pdf Peel M, Willman J, 2001, ``The dirty money that is hardest to clean up'' Financial Times 20 November Puri S, Ritzema T, 1999, ``Migrant worker remittances, micro-finance and the informal economy: prospects and issues'', WP 21, Social Finance Unit, International Labour Organization, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/finance/papers/wpap21.htm Roberts S, 1994, ``Fictitious capital, fictitious spaces: the geography of offshore financial flows'', in Money, Power, Space Eds S Corbridge, R Martin, N Thrift (Blackwell, Oxford) pp 91 ^ 115 Schepp D, 2002, ``New US laws target terror funding'' BBC News Online 25 April, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/1951482.stm Schmemann S, 2002, ``A nation challenged: sanctions and fallout; Swedes take up the cause of 3 on U.S. terror list'' New York Times 26 January, page A9 Scott-Joynt J, 2002, ``US terror fund drive stalls'' BBC News Online 3 September, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/low/business/2225967.stm Sica V, 2000, ``Cleaning the laundry: states and the monitoring of the financial system'' Millennium 29(1) 47 ^ 72 Siddiqui T, Abrar C R, 2001, ``Migrant worker remittances and micro-finance in Bangladesh'', Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit, International Labour Office, Dhaka, February, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/finance/download/bangla.pdf Tapper J, 2002,``A post-9/11 American nightmare'' Salon.com 4 September, http://salon.com/ news/feature/2002/09/04/jama/index np.html Thachuk K L, 2002, ``Terrorism's financial lifeline: can it be severed?'', Post-9/11 Critical Issues Series number 191, May, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, http://www.ndu.edu/inss/strforum/sf191/sf191.pdf The Economist 2001, ``Terrorists and hawala banking: cheap and trusted'', 24 November, page 97 The Economist 2002, ``Terrorist finance: follow the money'', 30 May, http://www.economist.com/ finance/PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story ID=1157691, accessed May 2002 Thrift N, 1994, ``On the social and cultural determinants of international financial centres: the case of the City of London'', in Money, Power, Space Eds S Corbridge, R Martin, N Thrift (Blackwell, Oxford) pp 327 ^ 355 Thrift N, 2001, ``Elsewhere'', in Capital Eds N Cummings, M Lewandowska (Tate Publishing, London) pp 82 ^ 105 Turner M, Alden E, 2001, ``US decision to close bank `will hit Somalis' '' Financial Times 9 November US Treasury, 2002 A Report to the Congress in Accordance with Section 359 of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 November, http://www.fincen.gov/hawalarptfinal11222002.pdf Weber C, 2002, ``Flying planes can be dangerous'' Millennium 31(1) 129 ^ 147 Wechsler W F, 2001, ``Terror's money trail'' New York Times 26 September, page A19 Weiner T, Johnston D C, 2001, ``A nation challenged: the paper trail; roadblocks cited in efforts to trace Bin Laden's money'' New York Times 20 September, page A1

532

M de Goede

White House, 2001a,``Fact sheet on terrorist financing executive order'', press release, 24 September, http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2001/09/print/20010924-2.html White House, 2001b, ``Shutting down the terrorist financial network'', Terrorist Financial Network Fact Sheet, press release, 7 November, http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2001/11/ 20011107-6.html Willman J, 2001, ``Special report inside Al Qaeda: trail of terrorist dollars that spans the world: suitcases of cash, informal money transfers, standard banking proceduresal Qaeda used them all to pay the bills of terrorism'' Financial Times 29 November World Bank, 2003, ``Global development finance 2003striving for stability in development finance'', 2 April, http://www.worldbank.org/prospects/gdf2003/ Yousef T M, 2001, ``Prepared statement of Dr. Tarik M. Yousef'', Hearing on Hawala and Underground Terrorist Financing Mechanisms, US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 14 November, http://banking.senate.gov/01 11hrg/111401/yousef.htm

2003 a Pion publication printed in Great Britain

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- StatementДокумент5 страницStatementNavneet BaliОценок пока нет

- Budget 2011-12 - FinalДокумент62 страницыBudget 2011-12 - FinalNavneet BaliОценок пока нет

- Ketan Parekh Scam-By Navneet BaliДокумент51 страницаKetan Parekh Scam-By Navneet BaliNavneet BaliОценок пока нет

- Practices in International Human Resource Management: Name: Navneet Bali Course: PGDFM 2010-12Документ15 страницPractices in International Human Resource Management: Name: Navneet Bali Course: PGDFM 2010-12Navneet BaliОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- News Writing: (Pagsusulat NG Balita)Документ71 страницаNews Writing: (Pagsusulat NG Balita)Hannah Allison AlcazarОценок пока нет

- DirectoryДокумент5 страницDirectoryKjeldzen Marie AgustinОценок пока нет

- The All BlacksДокумент8 страницThe All BlacksMartin da CruzОценок пока нет

- Resolution Regarding Taiwan's Future1999Документ3 страницыResolution Regarding Taiwan's Future1999dppforeignОценок пока нет

- Padilla V DizonДокумент12 страницPadilla V DizonKarlo KapunanОценок пока нет

- A. Bhattacharya - The Boxer Rebellion I-1Документ20 страницA. Bhattacharya - The Boxer Rebellion I-1Rupali 40Оценок пока нет

- My English Reader 6 (Ch.1Page16 - 27)Документ12 страницMy English Reader 6 (Ch.1Page16 - 27)Dav GuaОценок пока нет

- D.E. 17-35 Def. JT Mot. Sanctions, 3.11.19Документ37 страницD.E. 17-35 Def. JT Mot. Sanctions, 3.11.19larry-612445Оценок пока нет

- Voters Education (Ate Ann)Документ51 страницаVoters Education (Ate Ann)Jeanette FormenteraОценок пока нет

- Far and Away SummaryДокумент2 страницыFar and Away Summaryapi-347629267Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 6.emotionalДокумент20 страницChapter 6.emotionalMurni AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Publicaţie: Revista Dreptul 5 Din 2021Документ23 страницыPublicaţie: Revista Dreptul 5 Din 2021Neacsu CatalinОценок пока нет

- Valero Policy in St. CharlesДокумент2 страницыValero Policy in St. CharlesseafarerissuesОценок пока нет

- ICE Guidance Memo - Guidelines For The Use of Hold Rooms at All Field Office Locations (2/29/08)Документ4 страницыICE Guidance Memo - Guidelines For The Use of Hold Rooms at All Field Office Locations (2/29/08)J CoxОценок пока нет

- Julius Caesar..Документ41 страницаJulius Caesar..bharat_sasi100% (1)

- 206643-2017-De Ocampo Memorial Schools Inc. v. Bigkis20180320-6791-8qpzw7 PDFДокумент7 страниц206643-2017-De Ocampo Memorial Schools Inc. v. Bigkis20180320-6791-8qpzw7 PDFIsay YasonОценок пока нет

- Ricardo Luis C. Angeles Jeanne Lao HI166 - AH A Paper On The Religious Context During The Marcos EraДокумент6 страницRicardo Luis C. Angeles Jeanne Lao HI166 - AH A Paper On The Religious Context During The Marcos EraJeanneОценок пока нет

- Abacus Real Estate Development v. Manila Banking Corporation, G.R. No. 162270, April 6, 2005Документ2 страницыAbacus Real Estate Development v. Manila Banking Corporation, G.R. No. 162270, April 6, 2005Metsuyo BariteОценок пока нет

- Alen Hajdarevic: TK7866 16 OCTДокумент1 страницаAlen Hajdarevic: TK7866 16 OCTAlen HajdarevicОценок пока нет

- Money Claim FormДокумент3 страницыMoney Claim FormHihiОценок пока нет

- Peace and IslamДокумент34 страницыPeace and IslamMyk Twentytwenty NBeyondОценок пока нет

- PBCOM Vs AruegoДокумент1 страницаPBCOM Vs AruegoGeorge AlmedaОценок пока нет

- 7 - ED Review Test 7Документ3 страницы7 - ED Review Test 7huykiet2002Оценок пока нет

- Appellant.: Jgc:chanrobles. Com - PHДокумент2 страницыAppellant.: Jgc:chanrobles. Com - PHdsjekw kjekwjeОценок пока нет

- Unlawful Detainer Judicial AffidavitДокумент6 страницUnlawful Detainer Judicial AffidavitNicole100% (1)

- HWДокумент6 страницHWvinayОценок пока нет

- Verb + - Ing (Enjoy Doing / Stop Doing Etc.) : Stop Finish Recommend Consider Admit Deny Avoid Risk Imagine FancyДокумент12 страницVerb + - Ing (Enjoy Doing / Stop Doing Etc.) : Stop Finish Recommend Consider Admit Deny Avoid Risk Imagine FancyНадіяОценок пока нет

- Parricide - An Analysis of Offender Characteristics and Crime Scene Behaviour of Adult and Juvenile OffendersДокумент32 страницыParricide - An Analysis of Offender Characteristics and Crime Scene Behaviour of Adult and Juvenile OffendersJuan Carlos T'ang VenturónОценок пока нет