Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Ark

Загружено:

Ark Jes MalinganИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ark

Загружено:

Ark Jes MalinganАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

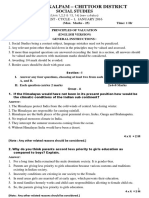

THE PROSPECTS OF MULTILINGUAL EDUCATIONAND LITERACY IN THE PHILIPPINES Ricardo Ma. Nolasco, Ph.D.

Acting Chair, Komisyon sa Wikang FilipinoSeptember 17, 2008 Abstract: This paper evaluates the chances for mother tongue-based multilingual education(MLE) to be institutionalized in the Philippines. In the past, pro-English proponents havem a n a g e d t o m o n o p o l i z e t h e academic and popular discourse on the language issue i n education. Their allies in the Philippine Congress have gone as far as to make English theexclusive medium of instruction for basic education. However, many stakeholders havebegun openly questioning the wisdom of the pro-English bills. Citing international andl o c a l research, they have suggested instead the primary use of the f i r s t l a n g u a g e i n elementary education and the strong use of the second languages (English and Filipino) atthe upper levels. How timely for this battle to ensue during the 2008 International Year of Languages.1. Introduction A basic weakness is plaguing Philippine education. It is that m a n y p u p i l s d o n o t understand what their teacher is saying and therefore they cannot follow the lesson. Why?Because the language in school is one they can hardly speak and understand.In a hearing conducted on February 27, 2008 by the committee on basic education andculture of the Philippine House of Representatives, various stakeholders in education urgedCongress to abandon moves to install English as the sole medium of instruction, especially in the primary grades.The Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino or KWF was one of these stakeholders. The KWFsuggested that a law be passed mandating the primary use of the learners first language (L1 or mother tongue) from preschool to grade 6, or at least up to grade 4. In our proposal, Filipino andEnglish should be taught at the elementary level but only as separate subjects, and not as media of instruction.We explained to the committee that the plan should provide learners, whose L1 is neither English nor Filipino, enough time to develop their cognitive, academic and linguistic skills intheir mother tongue. In the process, a solid foundation can be built for learning subjects taught inEnglish and Filipino in high school. By then learners will have mastered the academic languagein these two languages. The L1 can be used as auxiliary medium and/or as a separate subject.This paper discusses the prospects of institutionalizing mother tongue- or L1-basedmultilingual education (MLE) and literacy in the Philippines. It shall be divided into thefollowing parts: a) introduction; b) the linguistic situation in the Philippines; c) the countryslanguage-in-education policy; d) the international and local research in the use of language ineducation; e) support for MLE from various stakeholders; and f) conclusion Scribd Upload a Document Top of Form

multilingual edu

Search Documents Bottom of Form Explore

Ark Jes Malingan

Welcome to Scribd - Where the world comes to read, discover, and share... Were using Facebook to give you reading recommendations based on what your friends are sharing and the things you like. We've also made it easy to connect with your friends: you are now following your Facebook friends who are on Scribd, and they are following you! In the future you can access your account using your Facebook login and password. Learn moreNo thanks

/ 12 Top of Form

Bottom of Form Download this Document for Free 2. The linguistic situation in the Philippines The Philippines is a multilingual nation with more than 170 languages. According to the2000 Philippines census, the biggest Philippine languages based on the number of native speakers are: Tagalog 21.5 million; Cebuano 18.5 million; Ilocano 7.7 million; Hiligaynon6.9 million; Bicol 4.5 million; Waray 3.1 million; Kapampangan 2.3 million; Pangasinan 1.5million; Kinaray-a 1.3 million; Tausug 1 million; Meranao 1 million; and Maguindanao 1million.While it is true that no language enjoys a majority advantage in our country, the censusshows that 65 million out of the 76 million Filipinos are able to speak the national language as afirst or second language. Aside from the national lingua franca, regional lingua francas, like Ilokano, Cebuano, and Hiligaynon are also widely spoken.English is also a second language or L2 to most Filipinos. According to the Social W e a t h e r S t a t i o n s , i n 2 0 0 8 , a b o u t t h r e e f o u r t h s o f F i l i p i n o a d u l t s ( 7 6 % ) s a i d t h e y c o u l d understand

spoken English; another 75% said they could read English; three out of five (61%)said they could write English; close to half (46%) said they could speak English; about two fifths(38%) said they could think in English; while 8% said they were not competent in any way whenit comes to the English language.The self-assessment of Filipinos to speak and write in English and in Filipino may not beconsistent with their actual proficiency in those languages.For instance, in 1998, Guzman and her team administered proficiency tests to fiveseparate groups in Metro Manila. The groups consisted of: a) University of the Philippines undergraduate students (UP-U); b) UP law students (UP-L); c) undergraduate students from asectarian university (SU); d) undergraduate students from a private non-sectarian university(PNSU); and e) employees in a workplace (WP). Test items were selected on the basis of l e a r n i n g c o m p e t e n c i e s a n d s k i l l s expected of high school graduates as determined by t h e Department of Education. The results were as follows: Table 1. English and Filipino scores in P r o f i c i e n c y T e s t s administered to Participating InstitutionsU P U U P L SU P N S U W P E n g l i s h 6 7 % 7 7 % 4 8 % 3 3 % 5 6 % F i l i p i n o 8 2 % 8 3 % 7 8 % 7 1 % 8 2 % Source: Guzman et. al. (1998) Considering that students from the University of the Philippines are widely believed to representthe top 2% of all secondary school graduates, the figures indicate that English ability in other Metro Manila and provincial schools may be way below the UP average of 67% and closer to the33% average of students from the private non-sectarian university. The data further show better mastery by students and employees of Filipino 2

More recent figures give a clearer picture of the actual proficiency of Filipino students inthe two languages. In 2003-2007, the national achievement scores in English of fourth year students were found to

average at the 50-52% level, while their scores in Filipino were even lower. Table 2. National Achievement Scores in English and Filipino of 4 th Year High School Students in the Philippines for 2003-2007 2 0 0 3 0 4 2 0 0 5 0 6 2 0 0 4 0 5 2 0 0 6 0 7 E n g l i s h 5 0 . 0 8 % 5 1 . 3 3 % 4 7 . 7 3 % 5 1 . 7 8 % F i l i p i n o n a 4 2 . 4 8 % 4 0 . 5 1 % 4 8 . 8 9 % Source: Department of Education These data raise serious doubts about the capability of our high school students to handle contentin either English or Filipino. 3. Language-in-education policy in the Philippines Article XIV of the 1987 constitution provides that:For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippinesare Filipino, and, until otherwise provided by law, English. The regional languages arethe auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein.In pursuit thereof, the Aquino government laid down in 1987 the Bilingual Education policy which called for: the use of English and Pilipino (changed to Filipino) as media of instruction from Grade1 onwards: English, in Science, Mathematics and English; and Filipino in SocialStudies, Character Education, Work Education, Health Education and Physical Education; the use of regional languages as auxiliary media of instruction as well as initial languagesfor literacy (as spelled out in DECS Order No. 52)In 2003, the Arroyo government issued Executive Order No. 210 with the avowed purpose of (E)stablishing the Policy to Strengthen the Use of the English Language as a Mediumof Instruction. The order directed the following: English shall be taught as a second language, starting with Grade 1; English shall be the medium of instruction for English, Mathematics and Science from atleast Grade 3; English shall be the primary MOI in the secondary level, which means that the time allotted for English in all learning areas shall not be less than 70%;

Filipino shall continue to be the MOI for Filipino and social studies;Acting on the perceived desire of the president for a legislated return of English as theMOI, several representatives from the lower house filed three separate bills invoking similar purposes. 3

In his explanatory note to House Bill No. 4701, Representative Gullas said that as a resultof the bilingual policy, the learning of the English language suffered a setback. He cited two reasons for this: one is what he refers to as language interference (i.e. targeting the learning of two languages [English and Filipino] is too much for the Filipino learners, especially in the lower grades. Two, is the use of Pilipino which is actually Tagalog as medium of instruction as having limited the exposure of the learner to English, and since exposure is basic to languagelearning, mastery of the language is not attained.According to Representative Del Mar, a co-author of the English bill, the key to better jobs here in abroad is English because it is the language of research, science and technology,a r e a s w h i c h g l o b a l b u s i n e s s a n d employment is very much into. He pointed out that t h e teaching of English should start at the pre-school and elementary levels because the language proficiency must start at the childhood stage, the formative years and it would be more difficult to do so in older years.Representative Villafuerte, another proponent, mentions other reasons. He said thatcompared to its Asian neighbors, Filipinos find it easier to learn English because Philippine languages are phonetics-based and therefore can easily learn phonics-based English. He poses a second argument in that because the best quality educational and reading materials are inEnglish, the non-native Tagalog speaker has to translate the reading material into Tagalog first before (s)he can discuss the material intelligently with the teacher and among fellow learners.House Bill No. 4701, the original bill, was approved on third and final reading during the13 th Congress in 2006, with the support of 206 signatories. The measure provided that: English, Filipino or the regional/native language may be used as the MOI in all subjectsfrom preschool until Grade II; English and Filipino shall be taught as separate subjects in all levels in the elementary and secondary;

In all academic subjects in the elementary grades from Grade III to Grade VI and in alllevels in the secondary, the MOI shall be English;The bill however failed to materialize into law because there was no corresponding initiative from the Senate. In the present 14 th Congress, the English bill is now known as HouseBill 850 which has been consolidated with the two other versions, House Bills 305 and 446.There was another language-in-education bill filed by Representative Liza Maza which p u s h e d f o r t h e u s e o f t h e n a t i o n a l l a n g u a g e a s t h e p r i m a r y m e d i u m o f i n s t r u c t i o n . N o t surprisingly, this bill didnt survive through the committee level.3. International and local research in language in education International and local studies on the use of first and second languages in education allcontradict the arguments presented by the authors of the English bill.In a World Bank funded study, Dutcher in collaboration with R. Tucker (1994) reviewedthe international experience on this subject and found that: Children need at least 12 years to learn their L1. 4 Older children and adolescents are better learners of an L2 than younger children. This is because of the greater amount of experience and cognitive maturity that older childrenand adolescents have over younger children. Developing the childs cognitive skills thorough L1 is more effective than more exposureto L2. Knowledge and skills learned through the L1 need not be relearned but simplytransferred and re-encoded in the L2. Conversational language in an L2 can be attained within 1 to 3 years but success inschool depends on the childs mastery of the academic language which may take fromfour to seven years). Individuals easily develop cognitive skills and master content material when they aretaught in a familiar language. They can immediately add new concepts to what theyalready know. They need not postpone the learning of content before mastering an L2.Will increasing the time for English improve our English? Two longitudinal studies inthe United States suggest otherwise.Ramirez, Yuen and Ramey (1991) studied the effects on language minority children of the immersion strategy (all English curriculum), early-exit (1 to 3 years of L1) and late-exit (3 to6 years) bilingual programs. Their report showed that providing substantial instruction in thechild's primary language does not impede the learning of English language or reading skills. Inf a c t , L a t i n o s t u d e n t s w h o r e c e i v e d s u s t a i n e d i n s t r u c t i o n i n t h e i r h o m e l a n g u a g e f a r e d academically

better than those who studied under an all-English program. The report also indicated that as far as helping them (Latino students) acquire mathematics, English language,and reading skills was concerned, there was no substantial difference between providing a l i m i t e d - E n g l i s h proficient student with English-only instruction through grade t h r e e a n d providing them with L1 support for three years.The 1997 Thomas and Colliers study also arrived at similar findings. They found out t h a t a f t e r 1 1 y e a r s , U S c h i l d r e n w h o s e L 1 i s n o t English and who received an all Englisheducation learned the least amount of English. They also had the lowest scores in t h e standardized tests and could only finish between the 11 th and 22 nd percentiles. Those receivingone to three years of L1 instruction turned out scores which were good between the 24 th and 33 rd percentiles. On the other hand, students taught in their L1 for six years scored more than theaverage English native speaker in the English and academic tests. They ranked above the national norms at the 54 th percentile.H a s s a n a A l i d o u a n d h e r c o m p a n i o n s ( 2 0 0 6 ) s t u d i e d m o t h e r t o n g u e a n d b i l i n g u a l education in Africa. They underscored the crucial role played by the quality and timing of L2instruction. They found out that: It takes six to eight years of strong L2 teaching before L2 can be used as a medium. Bythen the learner has learned the academic language in the L2 sufficiently enough for this purpose. L1 literacy from Grades 1 to 3 helps but is not sufficient to s u s t a i n t h e l e a r n i n g momentum. Like in the Ramirez et al. and the Thomas and Colliers studies, the first three years of the childs education shows a jumpstart in the learning of L2 and academiccontent, with or without L1 support. This apparent progress is what deceives educators 5 into falsely concluding that the learners are making it. The beneficial effects of short term mother tongue instruction begin wearing off after the fifth year. The full benefits of long term L1 instruction (6 to 8 years) will only be evident after thetenth year. By then, knowledge in the L1 would have been

transferred to the L2 and would have promoted academic learning in an L2. L1 education when interrupted adversely affects the cognitive and academic developmentof the child. The Ramirez report also came out with the same conclusion: (W)hen l i m i t e d - E n g l i s h - p r o f i c i e n t s t u d e n t s r e c e i v e m o s t o f t h e i r i n s t r u c t i o n i n t h e i r h o m e language, they should not be abruptly transferred into a program that uses only English. The premature use of L2 can lead to low achievement in literacy , mathematics and science.What does local research say about these matters?Since the 1940s language-in-education studies have been conducted in the country precisely to provide a sound empirical basis for crafting policy.The First Iloilo Experiment was undertaken from 19481954 by Jose D. Aguilar who pioneered in the use of Hiligaynon as medium of instruction in Grades 1 and 2. The tests showed Hiligaynontaught children outperforming English-taught children in reading, math andthe social studies. The study not only showed L1 students being able to transfer the knowledgelearned in their L1 to English. It also found the L1 students catching up with the L2 students intheir knowledge of English within six months after being exposed to English as medium of instruction.O t h e r r e l a t e d p r o g r a m s t h a t c a n b e m e n t i o n e d are: the Second Iloilo LanguageExperiment (1961-1964); the Rizal experiment (1960-1966); the six-year First L a n g u a g e Component-Bridging program (FLC-BP) on transitional education in Ifugao province; and theliteracy projects of the Translators Association of the Philippines (TAP), responsible for developing literacy materials in more than thirty languages.The Regional Lingua Franca (RLF) Pilot Project was launched by the Department of Education under the leadership of Secretary Andrew B. Gonzales. It began in 1999 in 16 regionsand uses one of the three largest lingua francaeTagalog, Cebuano and Ilocanoas media of instruction in grades one and two, after which the children are mainstreamed into the regular bilingual program. The general objective of the program was to define and implement a national bridging program for use in Philippine schools.A total of 32 schools participated in the project, half (16) of which belonged to the experimental class and the other half (16) to the control class. There were five (5) schools whichemployed Cebuano as a medium, four (4) which used Ilocano and seven (7), Tagalog. The control schools implemented the bilingual scheme.The experimental and control schools were tested in mathematics, science, wika at pagbasa (language and reading), and sibika (civics/social studies) for year 1999-2000 and 2000-2001. The test results are as follows:

6 Table 3. Mean scores for Grade 1 under RLF project, SY 1999-2000 S u b j e c t A r e a T e s t e d E x p e r i m e n t a l G r o u p C o n t r o l G r o u p Cebuano N= 183Ilocano N= 115Tagalog N=264Cebuano N=186Ilocano N=109Tagalog N=253M a t h e m a t i c s 1 6 . 2 6 1 5 . 2 6 1 9 . 3 2 1 4 . 6 2 1 2 . 9 6 1 4 . 7 4 S c i e n c e 1 6 . 5 6 1 7 . 0 2 2 0 . 9 0 1 2 . 7 4 1 2 . 9 4 1 4 . 7 5 W i k a a t P a g b a s a 2 5 . 5 7 2 5 . 2 1 3 1 . 5 3 2 6 . 0 7 2 6 . 0 0 2 7 . 8 3 S i b i k a 2 2 . 0 1 2 1 . 6 9 2 8 . 7 8 2 2 . 7 6 2 1 . 5 3 2 4 . 8 0 Source: Department of Education Table 4. Mean scores for Grades 1 and 2 under RLF project, SY 2000-2001 S u b j e c t A r e a T e s t e d G r a d e 1 G r a d e 2 E x p e r i m e n t a l C o n t r o l E x p e r i m e n t a l C o n t r o l M a t h e m a t i c s 1 6 . 2 5 1 2 . 3 2 1 8 . 3 1 1 5 . 2 8 S c i e n c e 1 4 . 2 8 1 1 . 4 3 1 5 . 8 2 1 4 . 2 2 W i k a a t P a g b a s a 2 1 . 1 6 2 0 . 8 4 2 4 . 8 2 2 3 . 2 0 S i b i k a 1 5 . 0 8 1 6 . 3 2 Source: Department of Education F o r the first year of implementation of the RLF project, as shown i n T a b l e 3 , t h e experimental group obtained numerically higher scores than the control groups in all learningareas and in all lingua francae, except in wika at pagbasa in Ilocano and Cebuano. For the s e c o n d y e a r o f i m p l e m e n t a t i o n , Table 4 shows the experimental classes in both g r a d e s performing better in all subject areas, except in English where the Grade 2 pupils in the controlclasses were exposed to English since Grade

1.Based on the three year pilot implementation of the lingua franca project, the Dep-Ed concluded that: (The) Lingua franca has effectively helped children adjust to the school settingand learning tasks such as being able to read and write, solve math problems, understandingscience concepts and principles using the first language at home and eventually English as a second language.I t added: They (the pupils) became more interested in their d a y - t o - d a y l e a r n i n g activities. Comprehension was very evident as shown in (the) daily evaluation done. (With) Theuse of the mother tongue, the language the pupils have, the problem of communicating and expressing themselves freely had been overcome. T h e m o s t compelling L1-based educational program so far has been the LubuaganKalinga MLE program. This is being carried out by the Summer Institute of Linguistics-Philippines, the Department of Education and the local community of L u b u a g a n , K a l i n g a province. Already in its tenth year, the program covers three (3) experimental class schools i m p l e m e n t i n g t h e mother tongue-based MLE approach and three control c l a s s s c h o o l s implementing the traditional method of immersion in English and Filipino. Schools are of the same SES (Social Economic Status).Walter and Dekker (2008) and Walter, Dekker and Duguiang (to appear) reported andanalyzed the test results from grades one to three in these schools and sections for school years2006-07 and 2007-2008. The testing of the experimental classes and control classes were doneunder the following conditions: a) all experimental and control class students were tested; b) 7

The Prospects of Multilingual Education Download this Document for FreePrintMobileCollectionsReport Document Info and Rating

Jill Manapat Share & Embed Related Documents PreviousNext 1.

15 p.

19 p.

19 p. 2.

18 p.

39 p.

39 p. 3.

16 p.

4 p.

1 p. 4.

6 p.

4 p.

5 p. 5.

7 p.

5 p.

31 p. 6.

28 p.

13 p. More from this user PreviousNext 1.

47 p.

110 p.

6 p.

2.

5 p.

12 p. Add a Comment Top of Form

Bottom of Form Upload a Document Top of Form

multilingual edu

Search Documents Bottom of Form Follow Us!

scribd.com/scribd twitter.com/scribd facebook.com/scribd About Press Blog Partners Scribd 101 Web Stuff Support FAQ Developers / API Jobs Terms Copyright Privacy

Copyright 2012 Scribd Inc. Language: English

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Private Military CompaniesДокумент23 страницыPrivate Military CompaniesAaron BundaОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Lubbock Fair Housing Complaint NAACP TexasHousers TexasAppleseedДокумент27 страницLubbock Fair Housing Complaint NAACP TexasHousers TexasAppleseedAnonymous qHvDFXHОценок пока нет

- Full Drivers License Research CaliforniaДокумент6 страницFull Drivers License Research CaliforniaABC Action NewsОценок пока нет

- Learning Activity Sheet in Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21 Century Quarter 2 - MELC 1 To 3Документ10 страницLearning Activity Sheet in Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21 Century Quarter 2 - MELC 1 To 3Esther Ann Lim100% (2)

- KFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFДокумент28 страницKFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFWinner#1Оценок пока нет

- 07) National Land Titles and Deeds Registration Administration v. CSCДокумент2 страницы07) National Land Titles and Deeds Registration Administration v. CSCRodRalphZantuaОценок пока нет

- Bank Account - ResolutionДокумент3 страницыBank Account - ResolutionAljohn Garzon88% (8)

- Inventory of Dams in MassachusettsДокумент29 страницInventory of Dams in MassachusettsThe Boston GlobeОценок пока нет

- Parents Teacher FeedbackДокумент2 страницыParents Teacher FeedbackAditri ThakurОценок пока нет

- Jan 28 Eighty Thousand Hits-Political-LawДокумент522 страницыJan 28 Eighty Thousand Hits-Political-LawdecemberssyОценок пока нет

- Antonio Negri - TerrorismДокумент5 страницAntonio Negri - TerrorismJoanManuelCabezasОценок пока нет

- Mills To MallsДокумент12 страницMills To MallsShaikh MearajОценок пока нет

- Northern SamarДокумент2 страницыNorthern SamarSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Where Did The Dihqans GoДокумент34 страницыWhere Did The Dihqans GoaminОценок пока нет

- Cultural and Trade Change Define This PeriodДокумент18 страницCultural and Trade Change Define This PeriodJennifer HoangОценок пока нет

- Proposed Rule: Schedules of Controlled Substances: U.S. Official Order Form (DEA Form-222) New Single-Sheet FormatДокумент5 страницProposed Rule: Schedules of Controlled Substances: U.S. Official Order Form (DEA Form-222) New Single-Sheet FormatJustia.com100% (1)

- Washington D.C. Afro-American Newspaper, January 23, 2010Документ24 страницыWashington D.C. Afro-American Newspaper, January 23, 2010The AFRO-American NewspapersОценок пока нет

- Utopian SocialismДокумент3 страницыUtopian SocialismVlad E. CocosОценок пока нет

- Collin Rugg On Twitter Can Someone Tell Me What The Fired Twitter Employees Did All Day No, Seriously. Elon Fired 75 of ThemДокумент1 страницаCollin Rugg On Twitter Can Someone Tell Me What The Fired Twitter Employees Did All Day No, Seriously. Elon Fired 75 of ThemErik AdamiОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- 1em KeyДокумент6 страниц1em Keyapi-79737143Оценок пока нет

- Graduate Generals Theory Reading List As Revised For Circulation October 2010Документ10 страницGraduate Generals Theory Reading List As Revised For Circulation October 2010Fran_JrОценок пока нет

- An Introduction To PostcolonialismДокумент349 страницAn Introduction To PostcolonialismTudor DragomirОценок пока нет

- Giovanni Arrighi, Terence K. Hopkins, Immanuel Wallerstein Antisystemic Movements 1989Документ123 страницыGiovanni Arrighi, Terence K. Hopkins, Immanuel Wallerstein Antisystemic Movements 1989Milan MilutinovićОценок пока нет

- Letter To Swedish Ambassador May 2013Документ2 страницыLetter To Swedish Ambassador May 2013Sarah HermitageОценок пока нет

- Merlin M. Magalona Et. Al., vs. Eduardo Ermita, August 16, 2011Документ2 страницыMerlin M. Magalona Et. Al., vs. Eduardo Ermita, August 16, 2011Limuel Balestramon RazonalesОценок пока нет

- The Taste of NationalismДокумент26 страницThe Taste of NationalismDyah Shalindri100% (1)

- Comments From "Acknowledge That Aboriginals Were Victims of Genocide by The Federal Government"Документ14 страницComments From "Acknowledge That Aboriginals Were Victims of Genocide by The Federal Government"Ed TanasОценок пока нет

- Philippine History, Government and Constitution Course Outline and RequirementsДокумент3 страницыPhilippine History, Government and Constitution Course Outline and RequirementsJezalen GonestoОценок пока нет

- LA Times 0412Документ32 страницыLA Times 0412Flavia Cavalcante Oliveira KoppОценок пока нет