Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Dirty Thirty: A New Tradition For A New University

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Dirty Thirty: A New Tradition For A New University

Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

It was the year of the microchip, the birth-control pill, the space race, and the computer revolution;

the rise of Pop art, free jazz, sick comics, the New Journalism and indie films, the emergence of Castro, Malcolm X, and personal super diplomacy; the beginnings of Motown, Happenings, and the Generation Gap all bursting against the backdrop of the Cold War, the fallout-shelter craze, and the first American Casualties of the war in Vietnam. --Frank Kaplin, 1959: The Year Everything Changed.

The Dirty Thirty: A New Tradition for a new University

A New University Iowa States football history spans 117 years and its legacy includes some of the games greatest names. From Glenn Pop Warner to Clyde Williams, Johnny Majors and Earle Bruce, the Cyclone gridiron tradition includes great coaches and great teams. But perhaps no team in ISUs history so captured the nations imagination as the 1959 Dirty Thirty. This small group of Iowa State student-athletes would perform their magic against a backdrop of cathartic change in America and on the ISU campus. The biggest on-campus change was upfront and obvious in September of 1959. Iowa State, on the heels of its centennial celebration, was now Iowa State University, and its 9,500 students returning to campus couldnt help but see the difference. The Iowa State Daily reflected on the change in its first edition of the 1959-60 school year: The word college is being rubbed out almost everywhere. From the inch-deep engraved Iowa State College over the Beardshear pillars to the ISC stickers on every microscope and manhole cover owned by the University, the change is on. Stationary, decals, pennants, and other articles that advertised Iowa State College have been or are being sold out. The name change reflected decades of angst over what the school would call itself. For much of Iowa States early history, the institution was known simply as Ames by the average Iowan, to avoid confusion with the State University of Iowa in Iowa City. The use of the Ames moniker was so pervasive that until 1926, Cyclone student-athletes were given an A for their letter jackets. When fall camp opened for the 1959 season, Iowa State head football coach Clay Stapleton was starting his second season in Ames. His staff included first assistant coach Lou McCullough, who had played for Stapleton at Wofford College, and former Maryland All-American Bob Ward. Both were known as hard-nosed, demanding coaches. Bernie Miller, another Wofford man, and Arch Steele, who had coached at ISU since 1954, rounded out the staff. A native of Fleming, Ky., Stapleton played at Tennessee before embarking on his coaching career. He started his career at Wofford and then assisted at Wyoming from

1953-54 before moving on to Oregon State. In his three seasons in Corvallis (1955-57), the Beavers earned two trips to the Rose Bowl. What Stapleton found at Iowa State after taking the Cyclone head coaching position in 1958 left much to be desired. The media asked me, Clay, did you look at the facilities before taking the job? Stapleton recalled. I said, Hell no I didnt look at the facilities. Iowa States new athletics director was Gordon Slim Chalmers. The 48-year-old former Naval Lieutenant Commander during World War II had made the 1932 U.S. Olympic team as a swimmer. He cut an imposing figure at 6-5, 205. Chalmers had most recently been an assistant athletics director and head swim coach at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. Chalmers, too, had been shocked by Iowa States dated facilities, including the setup at Clyde Williams Field, ISUs football stadium. The stadium had been built in 1913 and seated about 20,000 fans. It had been named in 1938 for the former ISU football coach and athletics director who had spearheaded the drive to build the facility on the site of a peach orchard. Today its the intersection of Lincoln Way and Sheldon. After coming from the U.S. Military Academy to here, it is a letdown to see that shanty press box on top of the stadium, Chalmers said. There were bigger worries than the press box. Iowa States money situation was of such concern that ISU had contracted to play its 1963 Big Eight Conference home game vs. head coach Bud Wilkinsons powerhouse Oklahoma program at OU. The Iowa State payout for a road game before 60,000 Sooner fans in Norman would be higher than for a game in Ames. A similar arrangement was made for a 1963 game at Nebraska. Our financial situation is poor, Chalmers said. We have no (financial reserve). We will play at OU every year if it will help our program. It is the difference between $60,000 and peanuts. And we cant live on peanuts. We feel the same about Nebraska. ISU had averaged 10,456 fans during a 4-6 1958 season. In 1957, Oklahoma had drawn 53,392 fans in Norman against Iowa State. The new athletics director even intimated that unless there were new streams of revenue, Iowa State might have to leave the Big Eight or perhaps the decision would be made for ISU by the other league schools. Chalmers biggest challenge was to revive an instate series with Iowa. But the fruits of that quest would not be tasted until 1977. On Sept. 8, former Iowa State head football coach and athletics director George Veenker died. Veenker, ISUs coach from 1931-36, had served as athletics director until 1945. A

man of few, well-chosen words, Veenker was well aware of the challenges of winning at Iowa State. The head football coaching job at Iowa State is not for weak-minded coaches, Veenker said. It is not even for strong-minded coaches with weak moments. The records bears out Veenkers knowing commentary. Iowa State football had been a force in the years of World War II, because players from around the country had been sent to ISU for the V-12 program that churned out engineers for the war effort. But in the 1950s, coaches Abe Stuber (1947-1953), Vince DiFrancesca (1954-56) and Jim Myers (1957) had not produced a winning season. Iowa States all-time conference record heading into the 1959 season was 42-117. Mo Nichols, Captain of a Shrinking Squad Despite the past, there were reasons for cautious optimism heading into the 1959 season. Halfback Dwight Nichols, the pride of Knoxville, Iowa, returned as the unquestioned team leader. A hard-nosed bruiser despite his 5-10, 164-pound frame, the 25-year-old Nichols was a military veteran and no-nonsense performer on the field. Off the field Mo Nichols had a lighter side. He was an all-Big Eight selection as a sophomore and a junior while leading the league in total offense both years. Nichols came to Iowa State in 1956 after three years in the Marines. He was a longshot to make the the Cyclone squad but came on the recommendation of his high school coach, former ISU fullback Ray Klootwyk. Nichols was not the most talented member of the team, but his fierce determination and astute decision-making abilities set him apart from most others. Those abilities were readily apparent from the moment he put on an ISU uniform. In 1957, he led a comeback at Syracuse in a game where the vendors were selling black and gold memorabilia because they thought the Orangemen were playing Iowa. Nichols forced a 7-7 draw, leading a late comeback. It was unbelieveable, Nichols said. (The crowd) knew who the hell we were then. By 1958 it was obvious that Nichols was someone very special. He was named the Big Eights MVP as a junior, leading the conference in total offense for the second straight year. Dwight was the best, a truly tough, intelligent player who had the desire to play at the highest level for 60 minutes, Stapleton said. He could pass, run or kick, but his heart carried him on the field. Fullback Tom Watkins remembers Nichols zeal.

He was one of the toughest athletes on the field, Watkins said. He wasnt athletically gifted but he was determined to be successful. Right tackle Larry Van Der Heyden said Nichols was perfect for Stapletons single-wing offense. He was a tremendous competitor, Van Der Heyden said. He was a winner and set a good example for us. Our offense fit his talents well. Nichols did have some very athletic teammates, including end Don Webb, wingback Mike Mickey Fitzgerald and Watkins. All would be tested by Stapletons grueling preseason camp. You either did the program or you didnt, Watkins said. Some couldnt handle the rigors of training. Coach Stapleton was good with fundamentals. He took the best athletes he had and put them in the places he needed them. They wanted to see who wanted to compete, Van Der Heyden said. They ran a hard camp, but it paid off. Stapletons fall practice began with 42 players. A year ago, we started as many as eight first-year men (sophomores, because freshmen were not eligible then), Stapleton said at the time. This year we can start an experienced man in almost every position. We have four seniors, 11 juniors and 27 sophomores. That overall number continued to dwindle before the Cyclones would play their first game. Among those departing was linebacker Chuck Lamson. Lamson was an Ames High School all-stater whose father, Bob, starred for the Cyclones in the 1920s. Bob coached as an assistant in football and basketball at Iowa State. Chuck would go on to a distinguished playing career at Wyoming. Lamsons departure meant that Iowa States team had only seven native Iowans. The geographically diverse team hailed from 14 states. The remaining Cyclones believed in their coach. (Stapleton) was a good coach, Webb said. He believed in studying the game. When we watched film, it was like an intense classroom setting. You had to learn it before you could apply it. Practice was hard and people were leaving the team. The coaches believed in conditioning. Webb, who would be the teams leading receiver, was called the best athlete Ive ever seen by Van Der Heyden. But Webb got no breaks running wind sprints after practice.

Sometimes they would let you stop, if you crossed the line first, Webb said. The coaches would never let me go (inside). They had me trying to make five in a row before I could stop. Throughout preseason practice, Iowa States roster continued to shrink through two-a-day practices. When Gary Astleford broke his ankle, only 30 Cyclones were practicing. Late in the preseason, Nichols and his remaining 29 teammates had a meeting. Basically, we said if anyone else wants to quit, do it right now, Nichols said. Nobody else did. Murder, Khrushchev and Football as the Season Begins The week of the first game, the Iowa State campus was rocked by the brutal murder at Hawthorn Court of Moince Larson, 25, and her five-month old daughter, Kimery. Police arrested a neighbor, 20-year-old Barry Neil McDaniel, a third-year electrical engineering major. Less than a week later, McDaniel, without articulating any motive beyond an impulse to kill, pled guilty in Nevada to strangling the wife and daughter of a fellow ISU student. He was sentenced to life in prison. Iowa State opened the season Sept. 19 at Drake. Watkins breakaway speed and the passing and running of Nichols led ISU to a 41-0 Saturday night victory over the Bulldogs. The field was wet and muddy, but Watkins gained 137 yards on 23 attempts. Out of West Memphis, Ark., Watkins bought into Stapletons no-nonsense brand of single-wing football. (Watkins) was a great kid, and a great athlete who could compete against the best in our conference, Stapleton said. Kids liked him. Tom made us competitive. Watkins was a special player and his performance against Drake was an auspicious display of what Cyclone fans would enjoy over his final two seasons. Nichols rushed for 87 yards and passed for 93 at Drake, including six completions to Webb. The Cyclone defense was outstanding, allowing only six first downs and 100 yards in total offense. The sloppy field did not deter Iowa State students from tearing down a Drake Stadium goal post and parading it around the field. At the end of game, we looked like we had taken a mud bath, Van Der Heyden said. Following the contest, as the team entered the locker room area, ISU trainer Warren Ariail greeted them: "Here comes the Dirty Thirty!" The tag was an instant hit. The jubilant team gave Ariail the game ball.

Fifty years later, Ariail recalled the essence of the Dirty Thirty. They were a great group of well-rounded, hard-nosed kids, Ariail said. We had 22 players on the team who played offense and defense. There were another eight that were substitutes. I called them the big eight, just like our conference. Ariail, called Floogie by his friends because he walked like a flat-footed floogie was far more than the teams trainer. He had worked with Stapleton at Wofford. A former marine who fought in the Pacific during World War II, Ariails contributions toward keeping Iowa States last 30 football players healthy would never be underplayed by Stapleton. He was like a brother to me, Stapleton said. If you want to give any credit for turning our players into better athletes, give it to him. News of the Dirty Thirty christening took a back seat the next week to the Sept. 23 visit to Iowa State University of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and his wife, Nina. The stop was part of the first trip to the U.S. by a Soviet premier. At about 4:30 p.m. the Khrushchev motorcade arrived on campus led by 18 State Highway Patrol cars. Highly visible were four (some say three) enterprising (or perhaps entertaining) male students who dressed up in trench coats wearing fedoras and carrying violin cases. The exact message they wanted to articulate remains unknown. Iowa State Daily editor Tom Emmerson had worked with his staff on an appropriate front page to make an impression on Khrushchev. Originally, the idea was to print the entire front page in Russian. In the interest of time, only the headline was printed in Russian. Khrushchevs ISU visit didnt go exactly as planned. ISU Dean Helen LaBaron later recalled the premiers stop in McKay Hall, the home economics building. One would think that he was running for office and was trying to win the young people to his side, LeBaron wrote to Mildred Horton, Executive Secretary of the American Home Economics Association. Certainly he showed no real interest in anything the students were doing At one point he asked me how a boy, if he were going to marry one of these girls, could check on her efficiency; to which I replied if she were a graduate of Iowa State University, he did not need to check on her efficiency. At one point, while touring the Swine Farm one mile south of Ames, Khrushchev took diplomacy to a new level. If the pigs of our two nations can co-exist together, so we, the people, can also live together. Levity aside, the visit was a giant step for the leaders of East and West at the peak of the Cold War and remains a key date in University history.

Once Khrushchev headed out of Iowa, the Cyclones headed to Denver for their Sept. 25 game against a UD team that outweighed the Cyclones by an average of 18 pounds per man. This would be the common challenge for ISU all season. Only two players on the Iowa State team weighed more than 200 pounds. The offensive line of left tackle Jerry Schoenfelder (6-0, 203), left guard Dick Scesnaik (5-10, 172), center Arden Esslinger (511, 178), left tackle Dan Celoni (6-0, 192) and Van Der Heyden at right tackle (6-0, 190) was diminutive, even by 1959 standards. Overall, the Dirty Thirty averaged out at 179 pounds a man. Dirty Thirty, Dirty Thirty! On another wet field, at Denver, the Cyclones rallied to post a 28-12 come-from-behind victory. Trailing 6-0 late in the first half, Nichols connected on a 17-yard touchdown pass to Bob Anderson and ISU went into the locker room leading 7-6. In the second half, Nichols ran for two touchdowns and completed a 5-yard pass to Webb for another. As ISU left the Denver field, the players chanted "Dirty Thirty, Dirty Thirty, Dirty Thirty." A sports writer heard it, researched the background, and then told the sports world about the "Dirty Thirty." Stapletons great equalizer for the Cyclones major season-long weight and bulk deficit was the old school single-wing offense. The formation had its roots in the offenses of Glenn Pop Warner. Warner currently ranks sixth among all-time collegiate coaches with 318 wins between 1895 and 1938. He is not, however, given credit for his first wins at Iowa State. Warner came to Ames after graduating from Cornell, where he was a collegiate star. He started each football campaign with six weeks in Ames for preseason practice. He would stay for the start of the season between 1895 and 1899, coaching the Cyclones before heading south to Georgia, or to Cornell. Warner received $80 and expenses for his troubles at Iowa Agricultural College, as ISU was then known. Under Warners tutoring, the 1895 Iowa State team routed Northwestern 36-0 and found a nickname after the Chicago Tribune article the next day proclaimed Iowa Cyclone Hits Evanstontown. Once the dominant football formation, the single-wing had lost its luster after World War II. The 1952 Pittsburgh Steelers were the last NFL team to use it. The single-wing, however, was ideal for running misdirection plays and that was key to keeping defenses guessing. Stapleton was one of the last coaches to use the single-wing because he knew Iowa State didnt have the horses to utilize the smash-mouth, straight ahead T formation. Conscious of the single-wings decline, Emmerson said the Cyclone faithful were not totally sold on the formation heading into the 1959 season. I believe a lot of fans, myself included, were discouraged by the fact that we were not going with the flow nationally and had not forsaken the single-wing for the T

formation, Emmerson said. Students had low expectations for just about any Cyclone football team and 1959 was no exception. Stapleton was confident that the single wing allowed Iowa States smaller teams to compete in the Big Eight Conference. This group of little men have to play the single-wing for two reasons, Stapleton said. They are not big enough to handle man-on-man blocking. We have to use two-man blocks, the key of single-wing play. Single-wing football has to be played by hard-nosed youngsters. That is why the Dirty Thirty likes playing the single-wing. While Iowa State got set for its Big Eight opener against Missouri, the headlines were out of Iowa City. University of Iowa athletics director Paul Brechler was in a very public feud with legendary Hawkeye head football coach Forrest Evashevski. The Iowa head coach had taken the Hawks to the Rose Bowl in 1956 and 1958. Not surprisingly, Evashevski eventually won the duel and would replace Brechler as athletics director in 1960. Stapleton had established a positive relationship with Evashevski, which would later lead to the formative work of restarting the Iowa State-Iowa series. On Oct. 3, Missouri came to town to open Big Eight play a week after beating Michigan. The Tigers were the pre-season pick to represent the conference in the Orange Bowl because Oklahoma had gone the previous year and there was a rule that kept the league champion from going to Miami two years in a row. There was a little excitement in the pregame. Wet weather had shorted out the phone lines, so the coaches for Iowa State and Missouri could actually hear each other talking during warmups. Northwestern Bell fixed the problem prior to the start of the game but not before Mizzou head coach Dan Devine and athletics director Don Faurot had vented their contention that their coaching lines were tapped. Since both teams could hear each other, this did not sit well with Iowa State officials. Northwestern Bell, to commemorate the situation, created the Telephone Trophy, which is annually held by the winner of the Tiger-Cyclone matchup. The first half of the game was scoreless. Wingback Mickey Fitzgerald confused Missouri all day, gaining 59 yards on four attempts from a fake punt formation. But the Tigers, despite seven turnovers, scored once in both the third and fourth quarters to claim a 14-0 win. Stapleton was not happy after the game. Some of the calls in this game smelled, Stapleton said. They gave us a raw deal. Believe me, if there was holding going on, we werent the only ones doing it. The Tigers did hold Iowa State to a season-low 163 yards of total offense. The Cyclones were eager to get back on track the following Saturday, Oct. 10 at South Dakota. The weather in Vermillion, S.D., was nearly perfect, as was the ISU attack. The Cyclones gained 402 yards in total offense and held South Dakota to just 106, winning

41-6 before just 1,864 fans. Critics hailed the Dirty Thirty as "the best team that had ever played in Vermillion." Watkins scored three touchdowns. Financially, the trip was an Iowa State loss of $200. But the gridiron win set the stage for a pivotal game at Colorado. An Iowa State sophomore who grew up just outside of Knoxville, Tenn., John Cooper intercepted two passes in the South Dakota game. Having served in the Army for 15 months, Cooper still had the football bug and wrote letters to a long list of collegiate coaches, looking for an opportunity to play. McCullough heard of Coopers quest and Stapleton opened the doors on what would be a remarkable college football career. I had promised my wife that I would graduate from college and the only way I was going to college was on a scholarship, Cooper said. I had never been to Iowa before. Practice then was essentially 2 hours of scrimmaging. A lot of guys wouldnt pay the price, but I had no where to go and was determined to make it. Cooper says his military experience helped him deal with the challenging practices. Dealing with those coaches on the field it was yes sir, no sir, Cooper said. I had dealt with that before. Cooper was effusive about Nichols, a fellow military veteran. He was a great team leader, Cooper said. He was tough and loved the game. I dont think I ever met a player who loved the game more than Dwight Nichols. Dirty Magazines and Big Win at Colorado As September faded the movie Pillow Talk starring Rock Hudson and Doris Day was showing on campus. The front pages of most papers covered the TV quiz show scandal. By 1959, former big game show winner Charles Van Doren was testifying before Congress about how he was given answers to questions to keep him on the show for weeks. Gunsmoke and Wagon Train were the most-watched television programs. There was a culture clash of generations that played itself out in Iowa during the fall of 1959. Iowa Attorney General Norman Erbe had led a campaign to ban 42 obscene magazines from Iowas bookstore shelves. The Iowa State Daily questioned not the ban, but its motivations: We are among those who question the sincerity of Mr. Erbe it must be pointed out that theres nothing like an anti-smut campaign to help a persons political aspirations. Erbe did, indeed, run for governor and won the 1960 election to succeed Herschel C. Loveless as the states top executive. Further testing the cinematic waters was Blue Denim, a film adaptation of the 1958 Broadway play, staring Brandon De Wilde and Carol Lynley. The film challenged

existing mores with a personal look at teenage pregnancy and abortion. The movie was generally well received, but not by The Iowa State Dailys critic: Blue Denim is a rather juvenile attempt to do something adult which is unfortunate, because the Broadway play from which it is taken had come very close to being a truly adult attempt at something juvenile. As the Cyclones boarded their passenger jet for their Oct. 17 game at Colorado, another era was coming to a close. On Oct. 16, the Iowa State Daily carried the news that passenger train service from Ames would be ending. The Ames train depot, built in 1900, would see its last passenger service in 1960. The Daily staff didnt welcome this development on the heels of a proposed Board of Regents ban on cars on campus: Until thenhere we are, Ames-locked and the Board of Regents meets next week to consider banning cars on campus. Maybe the best idea of all is to stock up on supplies needed from the outside world for the cold months ahead. Iowa State athletic teams had started to make the transition from rail to air. The Cyclone wrestling team was the first squad to fly to a competition, a 1953 match at Colorado. The larger state schools of the Missouri Valley Conference had formed the Big Six Conference in 1928 with Iowa State, Kansas, Kansas State, Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma making up the league. Colorado joined the league in 1948 and Oklahoma State became a member in 1958. The Cowboys were scheduled in to play a conference football schedule in 1960 so the leagues name had changed to the Big Eight for the 1959 season, although there were seven conference football teams that fall. Iowa State had lost eight straight conference games as it prepared for the Colorado contest. The Buffaloes featured quarterback Gale Weidner, who ranked second nationally in total offense. Despite those facts, Stapleton was upbeat before the contest. I will be awfully disappointed if we dont win the game, Stapleton said. Size was a concern. We werent supposed to be able to compete, said Iowa State lineman Tom Ferrebee. We heard people in the crowd saying, They look like high school kids. No worries. Iowa States defense was in high gear as the Cyclones recorded a 27-0 shutout. Fitzgerald scored on a 17-yard run and caught a 50-yard TD pass from Nichols, who became the all-time ISU career total offense leader during the game. Nichols also ran for a pair of scores. Weidner was held to minus five yards rushing. The Dirty Thirty played so flawlessly against the Buffaloes that the coaching staff would rank it as the teams best game of the season. This was Stapletons first conference victory, and his players carried him off the field.

All 27 Cyclones who traveled played. The Des Moines Registers Maury White summed it up this way: (The Colorado win) should be classified as a victory for virtue White wrote. The smaller (18 pounds per man), well-informed, well-drilled crew did the basic things well, made few mistakes and won easily. Iowa State left Boulder with a few new friends, including the manager of the hotel where the team had stayed. Our hotel has hosted a good many visiting athletic teams, the proprietor said. Your squad is the best dressed and the best mannered I have seen. Nearly 50 years later, Stapleton did not mince his words about the importance of the win. It was the biggest win of my career, Stapleton said. Up to that point, I hadnt won a conference game. A Visit to the Knoll Back home, a crowd of students and fans gathered outside the Memorial Union to welcome the team back to ISU. The Cyclones flight home was delayed 90 minutes and it became apparent that any female students who continued to wait for the football team would violate curfew. Cheerleader Nancy Becker was proactive and went to the Knoll (the campus home of Iowa States presidents) to get President James H. Hiltons blessing for girls to stay out late. Hilton was himself an Iowa State graduate. Its too late to do anything campus-wide, Hilton said. But if anyone is late getting back from the rally Ill do all I can to help them. This was no small issue. ISUs freshmen female students were required to be in their dorms on weeknights by 8:45 p.m. The Friday curfew for women was midnight, Saturday 12:30 a.m. and Sunday 10:30 p.m. With Hiltons blessing, no more encouragement was needed. The crowd had grown and now walked down Lincoln Way through campus past Friley Hall and toward the womens residences, passing the Knoll. The crowd picked up a chant We want girls. A single female voice answered from the womens dorms: We want boys. The team bus reached Ames at 12:45 a.m. to raucous cheers from a crowd that included Hilton himself. More than 660 feet of toilet paper were draped on trees around campus. Excitement was building with the realization that the Dirty Thirty were something special.

We had picked up momentum and things kind of steamrolled, Cooper said. Homecoming and the Missing Cards Iowa State had some streaks to stop when it hosted Kansas State for Homecoming on Oct. 24. The Wildcats had won six straight games against ISU, including a pair of Cyclone Homecoming games. But confidence in the Dirty Thirty was growing. The Iowa State football program for that game crowed, No Cyclone team ever liked the idea of losing to the Wildcats, but this gangthe famed Dirty Thirtyhates losing even more than the usual team. Today, they swear, is the time to call a halt to the whole thing. Call a halt indeed. Kansas State was the Cyclones third shutout victim of the season, falling 26-0 before 13,899 fans, the largest Homecoming crowd in school history up to that time. It was sunny, but just 49 degrees with a 35 mile-an-hour wind at kickoff. The strong gusts blew the numerous streamers in the crowd south toward Lincoln Way. The afternoon belonged to Nichols, who passed for two touchdowns, ran for another and set a total offense record for one game with 269 yards. ISU outgained the Wildcats 466 to 202. The KSU win marked just one of two times since the formation of the Big Six Conference in 1928 that Iowa State ever shut out consecutive league opponents. There were some humorous moments. During the thick of the action, Stapleton eyed reserve Alex Pancho Perez on the field. Did you send (Perez) into the game? Stapleton asked an assistant. No coach, I didnt send him in, the assistant replied. He just went in with the others. Perez stayed on the field for seven plays before heading back to the sideline. Stapleton recalled years later that he wasnt that impressed with the victory. We had a letdown, which was natural after the Colorado game, Stapleton said. There had been another pre-game complication. Someone had stolen from the press box the 5,000 cards used for the card section at Clyde Williams Field. The manual forerunner of the jumbotron, the card section utilized a large student group which held up coordinated cards in unison to form giant school-spirit related messages. The cards were worth $2,000 and their disappearance necessitated a thorough campus search. Leighton Housh of the Des Moines Register sang Nichols praises after the Kansas State game, comparing his ability to take punishment on the field and come back for more to the steely resilience of 1959 American League MVP second baseman Nellie Fox of the pennant-winning Chicago White Sox.

Durable Dwight Nichols, the Nellie Fox of college football, had his best day as ISU won 26-0, Housh wrote. The bandwagon was now in full throttle as Iowa State had won two straight conference games for the first time since 1951. For his part, Kansas State head coach and former Drake mentor Bus Mertes said this was the best Iowa State team he had coached against. Housh wrote, Some 16,000 homecomers rubbed their eyes in disbelief, then crowded the sidelines to escort the Iowa State players off the field in the sudden realization that the Dirty Thirty are something special. Housh and his media mates wrote from the dilapidated Clyde Williams Field press box that gave Gordon Chalmers the creeps. A new press box would be ready for the 1961 season. Iowa State sports information director Harry Burrell, in the midst of a career that spanned four decades, would announce the plays over the public address system. By using a switch, he could then speak only to the media in the press box with further information. Reporting sports in the 1950s was a mans job. Women and children would not be allowed in the ISU press box until 1972. The ultimate celebration of the KSU victory ensued when Hilton canceled classes for the following Monday. Stapleton said he was still grounded with the task at hand. I like to get to work early and I like to have my breakfast before I go to work, Stapleton said. So after we had won a couple of games, I said to my wife Edith, are you going to fix my breakfast in the morning? Edith looked at me and said, Who do you think you are, Evashevski? Oh, those 5,000 missing cards? They were found the following Monday in the rafters above the wrestling room in the east side of Clyde Williams Field. The crime has never been solved. On another note, Stapleton with wry humor threatened to quit by 1970 if Chalmers didnt do something about the mosquitos on the practice field. The Dirty Thirty Rides Again A major showdown loomed as the Cyclones traveled to Lawrence, Kan., the following week for a tilt at Kansas. The game would go a long way toward determining who won the Big Eight team title. Just the previous week, the Jayhawks fought hard against Oklahoma, falling 7-6. Things would not go so smoothly for Stapleton and his team this time.

The weather threw ISU a curve before they even left. The Cyclones were to fly to Kansas City, departing at 2 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 30. The team bused to Des Moines for the TWA charter flight, which would take less than an hour. One problem. There was no plane. Iowa States plane had flown Navy to South Bend, Ind. for its game at Notre Dame. It was to then fly to Des Moines to pick up the Cyclones, who arrived at the Des Moines airport decked out in their school-issued blue blazers. The weather in South Bend however, was not good, and the plane was delayed. The jet eventually took off and headed to Des Moines hours behind schedule. The jet reached Des Moines at 7:30 p.m., but by then, the local weather had deteriorated. The plane circled Des Moines, but could not land. As the rain came down, Iowa State was left high and dry. Train connections didnt work. Finally, the whole team boarded a bus that started for Kansas City hours after its scheduled arrival there. As the team boarded the bus, one player suggested the headline The Dirty Thirty Rides Again. For Chalmers, it was a frustrating moment because ISU had crossed its Ts and dotted it Is on pre-travel details. We originally had our own TWA plane when we contracted with the airline, Chalmers said. But since then they had sold that plane and that is how we ended up depending on the Navy plane. I knew we could have a problem when the weather started getting bad at around 4 p.m. The Cyclones arrived in Kansas City at 2 a.m., rose for a 9 a.m. breakfast and boarded buses for Lawrence at 11 a.m. KU shut down ISUs potent offense and won the game 7-0 on a fourth-quarter 15-yard touchdown run by Curt McClinton. The Cyclone attack was blunted by five turnovers and Iowa State was outgained by the Jayhawks 307-195. Kansas All-American halfback John Hadl gained 95 yards on 14 carries. Iowa State also missed a pair of field goal attempts, but ultimately, turnovers deep in Kansas territory spelled the end for ISU. Despite the loss, Stapleton was so proud of his team that he remarked "How can you help but be proud of these kids? When off the field, Id rather be coach of the Dirty Thirty than President of the United States." Stapleton made a key decision after the KU loss. I decided that neither me nor my staff would call any plays from the bench, Stapleton said. I did this not because anything happened but because I feel that our plays might distract the thinking of our quarterback in the game. Back on Track

Temporarily thrown off balance, Stapleton and his troops were still in conference crown contention. Returning home for a Nov. 7 game against Nebraska, Iowa State would face off against a Cornhusker team that had ended Oklahomas string of 75 straight conference games without a loss with a 25-21 win, the previous weekend. It was the first conference defeat suffered by the Sooners in 13 years. The Iowa State program declared Todays game will match the most colorful major football team (the Dirty Thirty) against the perpetrator of the Big Eights top upset. Nearly 11,000 fans were on hand, including composer Meredith Willson, who was in town riding the coat tails of his famously popular musical The Music Man. Willson, a Mason City native, had even composed a new Iowa State song that the band played that day under his direction. The Iowa State marching band was a male-only organization of 100 members. One woman who came to ISU at the time with the intention of joining the marching band was told point blank. Ladies dont march. The musical tastes of college students were changing. In 1959, longtime Memorial Union director Harold Pride noted that weekend evening dances were fading in popularity as students could listen to records in their dorm room, play cards or leave campus by car to enjoy a brief respite elsewhere. Big band leader Woody Herman came back for another performance in the Memorial Union that fall. Herman and his clarinet had serenaded a packed house of 2,000 ISU students in the recent past. This time only 600 people, some who got in free, showed for the concert. Bobby Darins Mack the Knife held the top spot on the singles chart for most of the football season. Five of the first 11 No. 1 singles of 1959 were rhythm and blues recordings as the big band and standards singers took a back seat to Elvis Presley, the Fleetwoods and Frankie Avalon. The Britannica Book of the Year for 1960, had this to say about pop music of that time: In 1959, popular music in the United States reached a new low of illiteracy, vulgarity and dullnessthe menace of rock n roll continued through 1959, although it showed some signs of weakening. The Dirty Thirty showed no signs of weakening. It had snowed two inches on the Clyde Williams Stadium field the Thursday before the Nebraska game. Rotary snow brushes cleared the field Friday morning and the turf was ready for the 35-degree weather that greeted both teams Saturday. ISU held a 3-0 lead at halftime. Watkins broke the game open on the second-half kickoff with an 84-yard touchdown return - the longest play of the season. ISU increased its lead over the Cornhuskers to 18-0 after three quarters before winning 18-6. Watkins savored the kickoff return after the game.

It feels great, Watkins said. I didnt know I was gone until (Cliff) Rick and Nichols got rid of two Nebraska players. When I could see daylight, then I knew I was gone. Oh boy, it felt good. Watkins deserved the spotlight. He rushed for 108 yards on 21 carries, including a 32yard TD dash. Watkins and Nichols now ranked first and second, respectively, on the conference rushing list. The media spotlight had boosted Iowa States football brand both nationally and closer to home as noted by Ames Tribune sports editor Donald K. Smith. I see the players from Iowa States sister school are complaining about their story positions in the states many newspapers as compared to Iowa States, Smith wrote. For years, Iowa State has been played down in the sports pages and sometimes not even rated a two-column headline. Dont they know down Iowa City way that the days of a one-school grid dynasty are over? Icicles The Dirty Thirtys final home game would be a Nov. 14 date with San Jose State. The Spartans featured the talents of halfback and return man ONeal Cuterry. San Jose State had hosted Iowa State during the 1958 season, with ISU posting a hardfought 9-6 win. The temperature at kickoff for that night game had been 60 degrees and the official stats also note that there had been no wind. The 1959 return game in Ames would be a different story. On Thursday of game week, a nasty winter weather system took the state by storm. Several inches of snow blanketed central Iowa and the temperature dropped to eight degrees Friday morning as it continued to snow off and on. The Midwest freezer made the trip to Ames a true learning experience for the San Jose State players. More than half our team has never seen snow, San Jose sports information director Art Johnson said. We have played in rainstorms, windstorms, maybe even dust storms and stray typhoons but nary a snowstorm or icicle pageant in the Santa Clara Valley. When they arrived at Clyde Williams Field, San Jose players tiptoed around any snow that survived the three days of brushing the field leading up to the game. The field itself was soft about one inch down. Below that was just plain frozen tundra. The temperature hovered in the teens. The wind was slight but once a players hands became wet, it didnt take much to numb hands and feet. According to assistant coach Ward, the Cyclones had thought ahead and had a secret weapon. ISUs players had long underwear.

We got them just before the game, Ward said. We ordered ours from the same place that provides equipment for Iowa. The difference is they probably order nothing but large and extra large, while we go along with the small and medium. It became readily apparent from the opening kickoff that Iowa State would be playing against an opponent that couldnt wait to get back to San Jose, Calif., where the high that day was 59 degrees. It snowed again the day of the game, said Van Der Heyden. There was black ice on the field like it had snowed, iced over and snowed again. The San Jose State guys looked like they were on ice skates. The opening kick was fielded by Webb at the 23-yard line. He flew down the west sideline and made for the end zone and a touchdown. Iowa State went up 13-0 moments later when San Jose fumbled the ensuing kickoff and Nichols followed with a 3-yard run for a TD. The rout was on. Iowa State recorded one of its largest margins of victory ever with a 55-0 win over San Jose State. Nichols accounted for 149 yards in total offense, and the Cyclone defense intercepted four passes. San Jose States Cuttery was held to 35 yards of total offense. The win gave ISU a 7-2 mark, the best record in the Big Eight. Make no doubt, it was cold for both teams and the fans. The San Jose State players stood around like icicles, Watkins said. It was nothing to us even though I got two frost-bitten fingers. It was cold as hell, but we were hot on the field. The win was a great sendoff for the Cyclones four seniors. Ferrebee was given the game ball, which today sits in a trophy case of the Jacobson Athletics Building. But the weather and other factors kept the attendance down to 6,049. This for a team that had captured the nations imagination. Where Im from a day like this wouldnt faze the fans, Stapleton said. There is not another school in America with the record and the progress weve shown where the fans wouldnt fill the stadium to watch. Bert McGrane, the legendary Des Moines Register sports writer, commented on the season home attendance average of 10,349. The lack of appreciation shown the Cyclones for their inspiring effort this year has been astonishing, McGrane wrote. A section of the student body and the townspeople along with a trace of representation from alumni and friends seems to constitute the supporting body of the Cyclone community. McGrane then gave the Dirty Thirty what for him was the ultimate endorsement of their worth, comparing the Cyclones to Iowas 1939 team that featured the greatest Hawkeye of them all, Heisman Trophy winner Nile Kinnick.

In some respects, this 1959 team is entitled to consideration alongside the Ironmen of Iowa, who lifted Hawkeye morale to new heights 20 years ago. Another crowd reducer is mentioned on the first page of the games official stat book, which it notes it was the first day of pheasant season. Iowa State business manager Merl Ross, who worked at ISU from 1917-68, had yet to see a sellout up to 1959. Maybe the community isnt too athletic minded, Ross said. We have quite a few alums who buy season tickets, but there are a lot of alums around Ames who havent seen a game since they left school. Everyone all over the state seems to be talking about Iowa States football team, Ross mused. It doesnt seem to be bringing in extra customers. In reality, many students were somewhat nonchalant about attending games, into which they got in free with their activity card. In those days, we had classes on Saturday morning, Emmerson said. The stadium was just south of State Gym, which was easy walking distance from the library. Some students would finish classes, grab a bite to eat at the Memorial Union and then retreat to the library until around 3 p.m. or thereabouts. Then they would stroll over to the stadium to watch the second half of the game. The ticket takers usually let little kids into the games free beginning around halftime. After the season, the Iowa State alumni periodical The Alumnus underscored the attendance issue with a comment on page 3 of its December 1959 issue. Our players, coaches, and administrators were justifiably disappointed. They had counted on greatly increased alumni support. There was little thought about the crowd in the Cyclone locker room after that last home game. A trip to the Orange Bowl would be on the line when Iowa State would head for Oklahoma the following weekend. We thought about San Jose State last week and now well think about Oklahoma, Stapleton said. Nichols said only a victory would do. We want the whole works, and well have it, too, Nichols said. Last Stand A victory in the seasons finale at Oklahoma would mean a tie for the league title and the schools first-ever Orange Bowl berth. The Cyclones were even measured for the Orange

Bowl blazers they would wear in Miami, Fla., if they could be the first ISU team to beat the Sooners since 1931. The game was televised back to Iowa as Iowa States radio voice Dale Williams, worked in front of the camera. Williams started announcing Iowa State games on WOI radio in 1943. The first ISU game broadcast by WOI radio had been in 1921. WOI-TV began transmitting in 1950 and the telecast of a Cyclone road game was unprecedented. Many ISU fans were among the 47,000 spectators that day in Norman, Okla. The game was at Owen Field, which played host to the premier college football program of the decade, head coach Bud Wilkinsons Oklahoma Sooners. As head coach at OU between 1947 and 1963, Wilkinson fashioned a record of 145-29-4 overall and 93-9-3 in the Big Six, Big Seven and Big Eight. The Sooners won 12 conference titles during that span and a trio of national championships. Owen Field was an intimidating place to play. The crown on the field was so high that you could stand on one sideline and never be able to see the team on the other sideline, Cooper said. They had this Bermuda grass which had sharp edges on it. They marked the yard lines with lime. There were times you were tackled or tackling someone and had trouble breathing. Oklahomas star tailback was Prentice Gautt. The Oklahoma City native was the first African-American football player at Oklahoma. He had been the Orange Bowl MVP the previous January. By 1959, the Big Eight was in the process of integrating its athletic teams. ISU had done so years earlier. Iowa States current football stadium is named for Jack Trice, an African-American ISU player who was killed in a 1923 game at Minnesota. The Cyclones fielded another African-American player, all-conference lineman Holloway Smith, who lettered in 192627. It would be a quarter of a century before the next African-American, Al Stevenson of St. Louis, Mo. would grace an Iowa State football roster. By 1959, five AfricanAmericans, Ferrebee, Fitzgerald, Webb, Watkins and Joe Burden were playing roles in Iowa States football resurgence. Earlier that fall, Dr. Martin Luther King, who had founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, spoke at a Des Moines church. While King was wellknown as a civil rights advocate who led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, his visit in the Capitol City merited only a page three story in the Des Moines Register. King made an appearance at ISU during Relgion-in-Life Week, which according to the 1960 Bomb (the ISU yearbook) stressed the practical rather than the thelogical aspects of religion. Iowa State came into the Oklahoma game ranking third nationally in scoring defense (5.0), eighth in scoring offense (26.2) and ninth in rushing (240.1).

The Oklahoma game program from that day did not downplay the efforts of the Dirty Thirty and its leader. Nichols, (ISUs) durable little tailback from Knoxville, Iowa is in many respects the most remarkable back in college football. He is approaching a three-season total of nearly 3,800 yards rushing and passing, has averaged playing close to 50 minutes through 29 games and despite the fact that he has probably handled the ball 30 times per game, hasnt been severely (note severely) hurt. As a sophomore, he made Oklahomas allopponents team. As a junior last year, Wilkinsons Sooners voted him the outstanding player they met all season. Make no doubt, Nichols and his teammates paid a price for their long days on the playing field. I hurt every joint in my body, Nichols later said. I took a hell of a beating. The (opposing) coaches used to tell (their) players, Even if hes out of the play, hit him anyway. For older Iowa State fans, there was a distant sense of dj vu about the big game. In 1938, Iowa State had faced Oklahoma in Ames for the conference title. A crowd of 20,000 fans watched the Cyclones fall 10-0 at Clyde Williams Field to finish the season at 7-1-1. With Everett Rabbit Kischer at halfback and All-American lineman Ed Bock, the Cyclones faced OU without starting fullback Gene Wilder, who had broken his ankle two weeks earlier. Iowa State had not won a share of a conference title since 1912, when the schools football team played on ground that is now occupied by the Parks Library. The Titanic had only been at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean a few months. The OU game program from the 1959 showdown mistakenly switched the pictures of Dr. Hilton and Iowa governor Herschel C. Loveless. Oklahomas coaching staff and players would make no such error in locking onto Nichols and his teammates. The Sooners jumped to a 21-0 halftime lead behind the running of Gautt. Gautt, who later would become an associate commissioner of the Big 12 Conference, gained 110 yards on 14 carries. ISU closed the gap to 21-12 after three quarters, but the Cyclone regulars were on the field for most of the game. Oklahoma would substitute liberally by the rules of the time, sending in numerous replacements between quarters. We were pretty beat up by then, Nichols said. It took a toll. For the Dirty Thirty, the clock struck twelve. Gautt ran for two touchdowns, his last a 48yarder, in the fourth quarter to secure a 35-12 OU victory.

It was a bitterly disappointing loss for the Dirty Thirty. Today, the Cyclones would have been looking forward to the schools first-ever bowl trip. Instead, their great season had come to an end. Everybody started out about halfway scared, Webb said. We lost our composure in that first half. Oklahoma quarterback Ronnie Hartline gave Iowa States players their due. I think the Cyclones have a great first team, Hartline said. They dont have much depth, but they sure hit hard. They would hit me and then say, Kinda hurts, doesnt it. Stapleton gave high marks to Cooper, who was developing into a very good football player. I think Cooper was my best player today, Stapleton said. He has been used as a utility player most of the season, but he did an outstanding job today. Like many of his teammates who would return for the 1960 season, Cooper wanted more. Oklahoma is the greatest team we played this year, Cooper said. But I feel before we graduate, well take them. John (Cooper) and I and a lot of other sophomores and juniors hope to prove that we can beat OU in the next two years, said center Jon Spelman. Were going to prove that this was just a down day for us. We hadnt had a down day all year. Those did not turn out to be empty words. The Cyclones would beat the Sooners 10-6 in 1960 in Ames and then score a 21-15 victory over OU in Norman in 1961. It is the only time Iowa State has beaten Oklahoma in back-to-back seasons since the two teams first met in 1928. Legacy Today, Cooper takes great pride in his college performances and feels a special bond with the Dirty Thirty. I owe everything to coach Stapleton, his assistants and my teammates, Cooper said. The Dirty Thirty was a good, tough, hard-nosed team I am proud to be one who stuck with it the whole way. I played with great players like Don Webb, Mickey Fitzgerald and Larry Van Der Heyden. I was captain of the team my senior year (1962). Emmerson said Iowa State fans enjoyed the ride. The Dirty Thirty were tenacious, Emmerson said. They really fought hard even though they were not physically large. The early wins really captured the fans attention.

In fact, the Dirty Thirty outscored its opponents, 248-80. In seven games, the Cyclones shut out four opponents. God, that was fun. Iowa State was not just winning, but actually dominating. Although the Cyclones were denied an Orange Bowl bid, the national acclaim secured the squad a place among ISUs greatest teams. Nichols was named all-conference, AllAmerican, and academic all-conference, along with end Jon Spelman. Watkins and Webb also were named all-conference. Saturday, the 22 members of the Dirty Thirty will be introduced at the Iowa State-Iowa football game in Ames. That suits Van Der Heyden. We always wanted to play Iowa, Van Der Heyden said. They got all the publicity, but would never agree to play us. Sadly, Nichols will not be among the men returning Saturday. He passed away earlier this year. Nichols was named to Look Magazines All-America team after the season. At the ceremonies in New York, Nichols recounted the Dirty Thirtys story to a reporter. Before he was done, all the other All-Americans had gathered round to hear the story first-hand. Cooper went on to a successful career as a head coach at Tulsa, Arizona State and Ohio State. Watkins and Webb had long careers in the National Football League. Nichols earned a masters degree and tackled the corporate world. Every guy that I know on that Dirty Thirty team was successful, Nichols said. Im talking doctor of horticulture, airline pilotsevery single guy. We learned from those coaches. There was good news in the football attendance department. Hilton assured fans that we have no intention of withdrawing from the Big Eight, as has occasionally been rumored in a special message in The Alumnus after the season. The success of the 1959 Iowa State football team helped drive ticket sales higher the following year. The smallest crowd in 1960 was 14,686 for Drake. That total exceeded attendance of every home game at Clyde Williams Field the previous season. On Nov. 5, 1960, Merl Ross finally got his first sellout. Pictures were taken of Ross putting out the sold out signs in front of the ISU ticket office window. The Dirty Thirtys success had carried over into 1960 and beyond. Attendance would steadily rise with stops and starts until the building of a new football stadium became a realistic goal, in part because Stapleton chose as his successor a fellow Tennessee graduate, Johnny Majors. Majors 1971 and 1972 bowl teams at ISU set in motion the final drive to build what is now Jack Trice Stadium.

On Sept. 8, 2007, a sellout crowd of 56,795 watched Iowa State take on Northern Iowa in Jack Trice Stadium. It is a different time. But the path to ISUs place in the Big 12 Conference was in part cleared by 30 student-athletes who never looked back and put the Cyclone football program in a national limelight. After the season, a film was made detailing the Dirty Thirtys successes. It was narrated by Lindsey Nelson, the nations preeminent college football voice of that time. His participation was the another stamp of legitimacy on the profound change the Dirty Thirty had wrought as the University, Ames, Iowa, the U.S. and the world changed around them. In 2006, Stapleton, who succeeded Chalmers as ISU athletics director in 1966, told an interviewer that as Cyclone head coach, he had planted a tree at his Duff Ave. home. I checked and it is still there, Stapleton said. So too, is the legacy of 1959 and the Dirty Thirty.

Вам также может понравиться

- Afrikaans Caps Ip Home GR 4-6 WebДокумент118 страницAfrikaans Caps Ip Home GR 4-6 WebLiza PreissОценок пока нет

- Our Years in Pammel Court by Richard E. EckerДокумент15 страницOur Years in Pammel Court by Richard E. EckerSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- What America Read: Taste, Class, and the Novel, 1920-1960От EverandWhat America Read: Taste, Class, and the Novel, 1920-1960Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (3)

- Left to Themselves: Being the Ordeal of Philip and GeraldОт EverandLeft to Themselves: Being the Ordeal of Philip and GeraldОценок пока нет

- Clint Eastwood InterviewДокумент8 страницClint Eastwood InterviewLuis Monroy SánchezОценок пока нет

- The GreyДокумент4 страницыThe Greysamknight2009Оценок пока нет

- Baseball’s First Indian: Louis Sockalexis: Penobscot Legend, Cleveland IndianОт EverandBaseball’s First Indian: Louis Sockalexis: Penobscot Legend, Cleveland IndianОценок пока нет

- The Life Story of Elijah HancockДокумент8 страницThe Life Story of Elijah HancockLiz SnowОценок пока нет

- Louds or Muscungus: What's in A Name? by Charles FrancisДокумент3 страницыLouds or Muscungus: What's in A Name? by Charles FrancisCharlie FrancisОценок пока нет

- Summary of The OJT ExperienceДокумент3 страницыSummary of The OJT Experiencejunjie buligan100% (1)

- Monte Hale Western 061Документ37 страницMonte Hale Western 061paulmuni100% (1)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in MAPEH 8 - ATI-ATIHANДокумент6 страницDetailed Lesson Plan in MAPEH 8 - ATI-ATIHANMC Tuquero100% (1)

- Basic Concept of MarketingДокумент44 страницыBasic Concept of MarketingAbhishek kumar jhaОценок пока нет

- Fs 2 DLP Different Characteristics of VertebratesДокумент4 страницыFs 2 DLP Different Characteristics of VertebratesTerrence Mateo100% (1)

- The Gate HouseДокумент314 страницThe Gate Housekandhan_tОценок пока нет

- Nag of LankaДокумент18 страницNag of LankaRISHAV RAJОценок пока нет

- A Postcolonial Reading of Some of Saul Bellow's Literary WorksДокумент120 страницA Postcolonial Reading of Some of Saul Bellow's Literary WorksMohammad HayatiОценок пока нет

- Spring Hill College 1930-1950Документ28 страницSpring Hill College 1930-1950Christopher ViscardiОценок пока нет

- "Don't Blink" - VP Crossword PuzzleДокумент1 страница"Don't Blink" - VP Crossword PuzzleRex Parker100% (3)

- When You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It's Time To Go Home - Erma Bombeck - 1991 - HarperColinsPublishers - Anna's ArchiveДокумент272 страницыWhen You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It's Time To Go Home - Erma Bombeck - 1991 - HarperColinsPublishers - Anna's Archivecdc2023dkОценок пока нет

- LOOKING FURTHER BACKWARD: A Dark Foretelling of a Chinese Invasion on USA in the Year 2023 (A Political Dystopia)От EverandLOOKING FURTHER BACKWARD: A Dark Foretelling of a Chinese Invasion on USA in the Year 2023 (A Political Dystopia)Рейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- A Maritime History of the Stamford Waterfront: Cove Island, Shippan Point and the Stamford Harbor ShorelineОт EverandA Maritime History of the Stamford Waterfront: Cove Island, Shippan Point and the Stamford Harbor ShorelineОценок пока нет

- Little Big ManДокумент55 страницLittle Big MandscemciОценок пока нет

- The Firemaker: China Thriller 1Документ53 страницыThe Firemaker: China Thriller 1Quercus BooksОценок пока нет

- The Exile - Issue 285Документ24 страницыThe Exile - Issue 285docdumpsterОценок пока нет

- 1979 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент50 страниц1979 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- Commencement Address by F. F. Jorgenson, 1905Документ11 страницCommencement Address by F. F. Jorgenson, 1905Special Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- Herman Knapp Contract With The Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, 1887Документ7 страницHerman Knapp Contract With The Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, 1887Special Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- Cardinal Guild Minutes (First Section), 1904Документ7 страницCardinal Guild Minutes (First Section), 1904Special Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1980 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент54 страницы1980 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

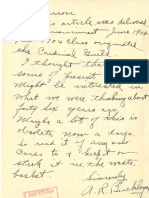

- Commencement Address by A. R. Buckley, 1904Документ14 страницCommencement Address by A. R. Buckley, 1904Special Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1968 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент31 страница1968 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1976 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент35 страниц1976 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1978 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент48 страниц1978 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1973 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент29 страниц1973 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1975 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент35 страниц1975 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1933 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент14 страниц1933 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1977 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент48 страниц1977 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1970 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент30 страниц1970 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1944 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент17 страниц1944 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1964 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент33 страницы1964 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1966 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент28 страниц1966 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1957 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент26 страниц1957 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1960 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент24 страницы1960 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1962 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент31 страница1962 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1946 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент14 страниц1946 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1939 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент18 страниц1939 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1935 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент12 страниц1935 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1963 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент25 страниц1963 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1954 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент24 страницы1954 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1929 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент22 страницы1929 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1931 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент19 страниц1931 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1920 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент18 страниц1920 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1927 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент25 страниц1927 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- 1924 Homecoming Football ProgramДокумент21 страница1924 Homecoming Football ProgramSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryОценок пока нет

- Learners Activity Sheets: KindergartenДокумент23 страницыLearners Activity Sheets: KindergartenShynne Heart ConchaОценок пока нет

- Las Q3 Science 3 Week 1Документ8 страницLas Q3 Science 3 Week 1Apple Joy LamperaОценок пока нет

- Cornell 2013-14 STS CoursesДокумент5 страницCornell 2013-14 STS Coursescancelthis0035994Оценок пока нет

- ESOL International English Speaking Examination Level C2 ProficientДокумент7 страницESOL International English Speaking Examination Level C2 ProficientGellouОценок пока нет

- Completed REVIEW Detailed Q&A December 2022Документ4 страницыCompleted REVIEW Detailed Q&A December 2022Hannan__AhmedОценок пока нет

- Ngene C. U.: (Department of Computer Engineering University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria)Документ17 страницNgene C. U.: (Department of Computer Engineering University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria)Oyeniyi Samuel KehindeОценок пока нет

- PAPER1Документ2 страницыPAPER1venugopalreddyОценок пока нет

- Challenge and ResponseДокумент40 страницChallenge and ResponsePauline PedroОценок пока нет

- Form - DIME Calclator (Life Insurance)Документ2 страницыForm - DIME Calclator (Life Insurance)Corbin Lindsey100% (1)

- Bco211 Strategic Marketing: Final Assignment - Fall Semester 2021Документ3 страницыBco211 Strategic Marketing: Final Assignment - Fall Semester 2021TEJAM ankurОценок пока нет

- Reading Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыReading Lesson Planapi-284572865Оценок пока нет

- ENGLISH-Grade 9: Answer Sheet Conditionals No. 1Документ4 страницыENGLISH-Grade 9: Answer Sheet Conditionals No. 1Ricky SoleroОценок пока нет

- Kindergarten CurriculumДокумент2 страницыKindergarten Curriculumfarmgirl71829656Оценок пока нет

- Lbs PHD Final LoresДокумент15 страницLbs PHD Final LoressaurabhpontingОценок пока нет

- Group 3 FLCTДокумент67 страницGroup 3 FLCTcoleyfariolen012Оценок пока нет

- Massimo Faggioli From The Vatican SecretДокумент12 страницMassimo Faggioli From The Vatican SecretAndre SetteОценок пока нет

- Savali Newspaper Issue 27 10th 14th July 2023 MinДокумент16 страницSavali Newspaper Issue 27 10th 14th July 2023 MinvainuuvaalepuОценок пока нет

- Kenya National Curriculum Policy 2017 (EAC)Документ33 страницыKenya National Curriculum Policy 2017 (EAC)Vaite James100% (1)

- SPM TEMPLATE AnswerSheetДокумент4 страницыSPM TEMPLATE AnswerSheetJueidris81Оценок пока нет

- Smith Benjamin ResumeДокумент2 страницыSmith Benjamin Resumeapi-494946300Оценок пока нет

- Live Lecture Versus Video Podcast in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Randomised Controlled TrialДокумент6 страницLive Lecture Versus Video Podcast in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Randomised Controlled TrialbamsweОценок пока нет

- ICSEClass 2 Maths SyllabusДокумент8 страницICSEClass 2 Maths Syllabussailasree potayОценок пока нет

- Lit PhilupdatedДокумент66 страницLit Philupdatedapi-25715639350% (2)

- ETS Global - Product Portfolio-1Документ66 страницETS Global - Product Portfolio-1NargisОценок пока нет

- Problem-Solution Essay: Grade 10 Done By: Ibtihal MayhoubДокумент7 страницProblem-Solution Essay: Grade 10 Done By: Ibtihal MayhoubSally M. HamzeОценок пока нет