Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Yakshagana

Загружено:

shakri78Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Yakshagana

Загружено:

shakri78Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

148

YAKSHAGANA

a

South

Indian

Folk

Theatre

MARTHA BUSHASHTON

Of India's many folk-theatre forms, Yakshagana (little known outside of Karnataka, South India) may be the most colorful, vigorous, and spirited. Heroic, mystical, splendid, fierce, savage, beautiful, it relives the legerids of the great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and themes from the Puranas, sacred texts of Hindu mythology. It is a theatre of battle scenes and heroism, loyalty and treachery, color and pageantry. Yakshagana has been known by several names in history, each revealing aspects of its true nature. Ancient audiences must have wondered at the performance of Dasavatara ("The Ten Incarnations of Vishnu"); they must have been titillated, teased, then amused by Bhagavatara ata ("the life of the divine Krishna, hero and god, mischievous lover of milkmaids"); then later there was the ebullience and vigor of KarubhantanaKalaga ("The Fight of the Black Warriors"). In each era the name of the theme became the title of the performing art. Others who considered themselves sophisticates contemptuously called this theatre Dombi Darara Kunita ("Antics of the Masked Rioters"). Perhaps its most common (and least colorful) alternate name is Bayalata ("performance in the open air"), which is still in use in the vil lages. But for over four hundred years now, Yakshaganais the name most widely used and recognized. Early solo performers, usually women, wore the costume of a Yaksha (demi-god) and interpreted the story through song (gana) and dance. Hence the name Yakshagana ("Songs of the DemiGods"). Presentations of Yakshagana are either as Tala Maddala, performed indoors without costumes, make-up, or dance; or as Bayalata, the fully costumed and acted performance in the outdoor arena. In a Tala Maddala performance, the Bhagavata (narrator) and the musicians sit center-stage, the actors on either side, facing each other, interpreting the songs and acting out the roles with hand gestures and facial expressions. Plays more suited to this kind of performance-those of literary exposition, sophistry, and argument-are chosen to suit the limitations of the performance. Generally the indoors form is performed during June through August, when the color, vigor, and enthusiasmof out-of-doors Bayalata performances would be swept away with the monsoon rains. After harvest time the performance blossoms into the open air as Bayalata. The Yakshagana stage is set before the village temple, on a sandy beach, or in open fields.

A low platform, about 16' by 20', with bamboo poles fixed at each corner, is garlanded with flowers, plantain and mango leaves, and roofed with matted palm leaves. At sunset the piercing sound of the chande, a high-pitched drum, announces the forth-

coming performance.

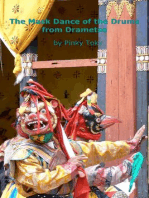

A romantic hero wearing the elaboratepyriform headdress.

150 Just before sunset the actors perform puja, prayers for a successful performance.These are offered to Ganesha, the elephant god, and to Subrahmanya(Skanda), the serpentheaded son of Lord Shiva. Some troupes sing puja in the open-air "greenroom" placed well away from the stage and elaborately set up with straw mats and fenced with palm leaves. Sometimes puja becomes an onstage ritual, performed by the clown, to the god whose image is ceremoniously placed centerstage. At other times, two will come on stage boys, the mandangopala, to exhort their god to clear all obstacles to The singing of the puja just before performance.

MARTHA BUSH ASHTON

a successful performance. Puja, an invariable part of Yakshagana preliminaries, is common to other South Asian theatre forms and is essential in the belief of audience and actors alike. Completed at sunset, puja heralds the beginning of the performance. Approaching darkness envelopes the audience and the stage, now lit only by flickering torches or the yellow glow of gas lamps. With gods implored, the junior Bhagavata (narrator), clowns, and musicians enter the stage area. The musicians with their instruments-always a chande; either mridanga or maddala drums; cymbals or gongs; and either harmonium,mukha veena, or pungiprovide a background for the clowns, who entertain the spectators with witty remarks,humoroussongs, and dances. Favorite female characters, appearing with or immediately following the clowns, are the "constantly jealous wives of Lord Krishna"who suggest, with song and dance, the basic theme of the play. Ancient dances of the Balagopala (Krishna and his brother Balarama), of Indra (the Vedic war-god), of Ardhanari (half-Shiva and half-Parvati deity), of Yakshini (demi-goddess), and groups of women dancers, once included, have long been omitted in attempts to shorten performances. Exquisite costuming, and extremely elaborate and meticulously-applied make-up, readily enable Yakshagana audiences to identify characters as either "gentle" or "fierce."The gentle charactersare the chivalrous (kings and warrior heroes) and the romantic (Gandharvas and Kiratas). The chivalrous gentle characters have massive oval, fluted, or pointed crowns anchored on their heads. The kireeta crown (see photo) is surmounted by a lotus, flanked by two graceful swans with red flowers in their beaks, the whole being topped with peacock feathers. Filmy red or white drapery flows from the back of the crown and is tucked in the waistcoat at either side. For the audience, this headdress immediately characterizes royalty and deities such as Rama and Krishna,incarnationsof Vishnu. Waistcoats are of rich blues, greens, or reds, intricately decorated with glass beads. Patterned breast pieces crossed on the chest are worked with colored stones and embroidered with gold. The dhoti (a long Hindu loin-cloth) is usually in orange, red, and

YAKSHAGANA

black checks. A swath of material, lined in bright red, is wound around the waist, over the chest, knotted at the back, and left hanging behind. Chivalrous characters (other than Vishnu and his incarnations) wear plain pink or yellow rice-flour base make-up. A characteristic and distinctive forehead mark (tilak) forms a brilliantred design againstthe pale make-up. Mustaches are always made of black cotton threads, yet beards, if worn by gentle characters,are always painted on. The face and limbs of characters representing Vishnu or any of his incarnations are painted blue-legend attributesthis color to him. Romantic gentle characters such as the vain, pompous, and foolhardy Gandharvas (heavenly musicians) and Kiratas (foresters and mountaineers) wear similar make-up but are readily distinguished by their huge pyriform headdress (see photos). A mundas (turban) is red or black and radially striped with broad bands of gold and silver. The actor securely ties the material An actor assemblingthe mundascoil by coil. of the mundas to his hair, worn long for this purpose, and builds the headdress coil by coil. After every coil, the mundas is pulled tight with cords, its weight being such that during vigorous dancing in a performance, the security of attachment is severely challenged. Three hundred yards of ribbon, colored strings, and silver and gold bandscomplete the headdress. Commoners such as brahmins, sages, or clowns wear loose garments without decoration.Female characterswear saris. The fierce characters include demons and, even more frightening, the "terrifying aspects of divinity." Demons wear an elaborate costume and a most complicated, grotesque, and horrifying make-up. The demon king wears a disproportionate white beard and mustache, and a string of white rice-flour paste dots provides a decorative framework (chutti) for his face. Although it appears mask-like, the make-up of the fierce charactersis very plastic. The "terrifying aspects of divinity" such as Sugriva (the monkey-king), Chandi (a fierce aspect of the Mother Goddess), and Narasimha (the man-lion) have their own individual designs in make-up. Leading characters adorn themselves with ear decorations, chest decorations, necklaces, garlands, epaulettes, bracelets, beaded girdles,

Romantic gentle characters, wearing the mundas,perform heroic dance.

The elaborate step-by-step revelation and introduction of major characters.At left, the musicianswith mridangaand the Bhagavatawith tiny cymbals. and anklets. Final touches are added with and carrying of maces, bows and arrows, and/or swords. The shrill sound of the chande and the Bhagavata'ssong signals the entrance of the main characters.Two stagehandsenter and hold up a piece of cloth that serves as a curtain. To the throb of continuous drumming the gentle characters enter dancing and one by one stand behind the makeshift curtain. At first only the crown is shown to the audience, then a profile of the face, finally a full face, then they exit. The fierce charactersfollow. They enter, reveal themselves step by step in all their terrifying splendor, then leave the stage. (In more spectacularperformances,resin or some inflammable dust is thrown into the torches as the demons enter, and the flames leap and stagger in the darkness.) Only major characters are introduced in this way; then the curtain is snatched away, clearing the stage for action. The Bhagavata sings the prologue of the play, in raga form, accompanied by the cymbals, mridanga, and chande. The tempo of the prologue quickens and as the name of each character is mentioned, the actor enters and dances appropriatelyto his role. After each dance, the dancer, in character, is questioned by the Bhagavata, who then introduces him to the spectators. Alternatively, the character introduces himself to the audience and tells them the reason for his presence. From a huge repertoire, the Bhagavata chooses 250 to 300 songs that he will sing

A demon.

153 tumes and ornaments, and travel seven or eight miles to the next village. It is here that they eat their first meal for the day, then sleep from midday until late afternoon, and the cycle begins once more as they prepare for the night's performance. As most present-day Yakshaganaperformers are still farmers,the touring season cannot begin until after the harvest in November or December, and must end in May before the monsoonsbegin. The early history of Yakshaganais a subject of scholarly disagreement. Some historians claim that the dance-dramathat preceded Yakshaganawas called Kuravanjiand was performed by the tribes of the Kurava, Chechu, and Yakshacommunities.The Kuravanji was an unsophisticateddrama;it consisted of pure dance performed between long narrativesongs. In those times a single female artist narratedand danced the story. The next development was the addition of a male dancer-narrator. Later came the Demon king, face framed by chutti. clowns for comic relief, and a female fortune teller. Gradually more performers were added to play the various roles.1 to give continuity to the particular performance. He sings a short passage from the Other scholars agree that the dance-drama from the performanceof a single song, sometimes just a line, in a high- developed female artist, but claim that the Yakshagana pitched voice, keeping rhythm (tala) by in the temples by the brahmin beating gong or cymbals, and accompanied performed the Bhagavata sings, priests developed from a dance-drama by the drums. While the actors gesturally interpret the short se- called Babu Nataka which depicted the variousmanifestationsof Lord Shiva.2 quence. Then the Bhagavatais immediately silent; the actors repeat the action or the During the seventh, eighth, and ninth cendance of the previous sequence, acting out turies A.D., the religious faith of the peothe same lines but speaking extemporaneple was threatened constantly by the unous dialogue. The Bhagavatathen sings an- certain political conditions in the country. other line and so the play goes on. The The brahmins took it upon themselves to pattern is repeated constantly until the spread their religion and preserve the point of climax-almost invariably the bat- dance-drama,using each for the benefit of tle scene between hero and enemy. The the other. From this time on Yakshagana combatants,shouting wildly, leap and swirl has been performedonly by men.3 to the increasingly frenzied drumming of the chande. Alternately leaping at each The earliest reference to the brahmins, called Brahmana melas, is c. 1502 A.D. other, then landing in a sitting position, the With the patronage of the Vijayanagar dancers maintain exact rhythm with the Emperors in Andhra region, the brahmins drum. The performance lasts all night and is generally timed so that the war dance climaxes at dawn. As the hero conquers his foe, the sun rises. The Bhagavatasings the concluding song, and the actors retire to offer a final song to Ganesha. Yakshaganaperformers follow an exhausting daily routine. After almost twelve hours of performance,they pack their cosNatraj Ramkrishna, "Kuchipudi Bhagavatham (History of the Dance Dramas of Andhra Desa)," Proceedings of the Seminar on Drama (Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi), p. 316. 2 EnakshiBhavani,The Dance in India (Bombay: D. B. TaraporevalaSons and Co., (Private) Ltd., 1965), p. 56. Ramkrishna,p. 318.

154

MARTHA BUSH ASHTON

traveled from Kuchipudi to various places performing dance-dramas based on the Shiva Puranas. Later, under the influence of Vaishnavism, themes were also taken from the BhagavataPuranas. According to K. S. Karanth (leading Kannada novelist, playwright, and patron of Yakshagana)the earliest known patrons were the Keladi kings, once feudatories of the Vijayanagar kings (1336-1565).4 A stone inscription (1556) on a Lakshmi-Narayana temple mentions a land grant for the specific purpose of "Talamaddale seva" (indoor Yakshagana).5 A 1557 manuscript of a Kannada poet gives a brief description of a Yakshagana dance-drama.6 Certainly Yakshagana was an established theatrical form at this time. After the fall of the Vijayanagar Empire many scholars and persons trained in the performance of the dance-dramasmigrated to the Tanjore district in Tamil Nad, where they were given shelter, land, and encouragement by the Nayak kings (c. 15611614). Karanth states that the oldest play found is dated 1564 A.D.7 By the 1600's,the composers were writing down their expressions of devotion to God through songs and dance-dramas. There seems to be no information on the period between royally patronized Yakshagana and the Yakshaganaperformed by the village people. In this igricultural society there were times for ploughing the fields, waiting out the monsoons, and sowing. During the time of waiting for the harvest, the elders of the village chose the play and the cast for the upcoming Yakshaganaperformance. By the time the crops were harvested the illiterate villagers had managed to learn their parts. The performance was the cooperative achievement of the whole village, from the carpenters who built the platform to the landlord who lent them rich costumes. There was a sense of security and thankfulnessfor the harvest -it was a time for celebration, and they did just that for about twelve hours. 'K. S. Karanth, "Yakshagana:A Musical Dance Drama" YakshaganaBallet Souvenir (Bombay: Sanjay Press, n.d.), p. 38. 'K. S. Karanth, "Yakshagana," Marg, XIX, No. 2 (March, 1966). BKaranth,Yakshagana Ballet Souvenir,p. 38. 7 Karanth,Marg, (March, 1966).

The preparationand completed creation of Narasimha,the man-lion.

YAKSHAGANA

155

Yakshagananot only entertained but gave religious instruction and familiarized the villagerswith the fine arts. By the middle of the 19th century, family troupes had developed from the individual village troupes. One such group performed in Sangli, Maharastra.The chief of Sangli was so impressed with the performance that a Maharastriantroupe was organized. From this time on the Karnatak village drama began to decline. The Maharastrian troupes soon came into vogue and were imitated by their inspirators.Eventually the villages gave up their own folk-troupes and waited for the touring shows, which were financed by the wealthiest man in town, but still performed for the enjoyment of all who cared to attend. Other major threats to local village folktheatre appeared.The new class of English, educated literates translated Sanskrit and English plays into Kannada and often these were taken up by local or touring groups because of their simple costuming, ease of production, and new themes and stories. Motion pictures, with their almost unlimited use of scene and sound, low cost, and facility of display in South Indian villages, have swept through the area and today are the major source of village entertainment. There are now approximately 12 Yakshagana troupes extant. Some troupes have The kireeta crown, worn by chivalrouscharbeen continuously associated with particular temples for 150 years, and their per- acter. Note red forehead mark (tilak). formances are financed by patrons who vow to hold a Yakshaganaperformance in thanks for, say, the overcoming of an illness. Less fortunate troupes, lacking support, have somewhat debased the art through imitation of popular films, and from economic necessity have discarded the traditional make-up and costumes. In these received with critical acclaim but little interest.) Yakshagana is best recompanies stories are no longer taken from public where audience tastes are ceived simple and the Ramayana or Mahabharata but are unsophisticated. To view it outside of its "cock and bull stories, where a devil, God, of perand street merchant can rub shoulders, and environment is to lose the subtlety formance through the long hours of darktalk any amount of nonsense and make ness under the flickering lights of a theatre people laugh."8 open to the sky and air, with the sounds There have been several recent attempts to of village night life behind the beat of drums. revitalize Yakshagana, but the form has Yakshagana radically limited appeal for modern urban audiences. (Dr. Karanth's own troupe was All photographs used in this article were taken from transparencies kindly lent by Dr. Edward B. Harper, University of 8 Ibid. Washington (Seattle).

Вам также может понравиться

- Essentials of Yakshagana PDFДокумент6 страницEssentials of Yakshagana PDFAyush DwivediОценок пока нет

- Yakshagana and Modern TheatreДокумент10 страницYakshagana and Modern Theatreswamimanohar100% (4)

- Folk Dances of South IndiaДокумент21 страницаFolk Dances of South IndiaUday Jalan100% (1)

- Nayika Bhedas - Classifications of the Female ProtagonistДокумент3 страницыNayika Bhedas - Classifications of the Female ProtagonistLakshmi SrinivaasanОценок пока нет

- Artograph Vol 02 Iss 04Документ40 страницArtograph Vol 02 Iss 04ArtographОценок пока нет

- Rupakas, Types of Sanskrit DramaДокумент3 страницыRupakas, Types of Sanskrit Dramarktiwary50% (2)

- Folk Theatre Andhra Yakshaganam Its TradДокумент9 страницFolk Theatre Andhra Yakshaganam Its TradManju ShreeОценок пока нет

- The Eight Nayikas of Indian Classical Dance and ArtДокумент8 страницThe Eight Nayikas of Indian Classical Dance and ArtShyam SrinivasanОценок пока нет

- Exploring the Nine Rasas of Indian Art and EmotionДокумент15 страницExploring the Nine Rasas of Indian Art and EmotionVishal JainОценок пока нет

- Darshan and AbhinayaДокумент9 страницDarshan and AbhinayaUttara CoorlawalaОценок пока нет

- Artograph Vol 01 Iss 06Документ20 страницArtograph Vol 01 Iss 06ArtographОценок пока нет

- Bharata NatyamДокумент12 страницBharata NatyamArunSIyengarОценок пока нет

- Shankar Bindu SДокумент355 страницShankar Bindu SСавитри ДевиОценок пока нет

- Prabandha Vol51 - 2016 - 1 - Art17 PDFДокумент13 страницPrabandha Vol51 - 2016 - 1 - Art17 PDFsingingdrumОценок пока нет

- Jayakrishnan - Kavitha / Dancing ArchitectureДокумент114 страницJayakrishnan - Kavitha / Dancing Architectureboomix100% (1)

- JayadevaДокумент4 страницыJayadevasrikanthsrinivasanОценок пока нет

- Indian Dramatic TraditionДокумент75 страницIndian Dramatic Traditionanjumvyas100% (2)

- Krishnan, Inscribing PracticeДокумент10 страницKrishnan, Inscribing PracticeeyeohneeduhОценок пока нет

- 13 - Chapter 7 PDFДокумент84 страницы13 - Chapter 7 PDFVignesh VickyОценок пока нет

- Abhisarika NayikaДокумент113 страницAbhisarika NayikaSri Hari100% (2)

- Jayadeva's GitagovindaДокумент4 страницыJayadeva's GitagovindaChan ChanОценок пока нет

- New NavarasasДокумент43 страницыNew NavarasasKiranmai Bonala100% (1)

- Final Journal 2Документ60 страницFinal Journal 2Swetha NikaljeОценок пока нет

- Gender, Culture, and Performance Marathi Theatre and Cinema Before Independence by Meera KosambiДокумент413 страницGender, Culture, and Performance Marathi Theatre and Cinema Before Independence by Meera KosambiPranay DewaniОценок пока нет

- A Brief Overview of The MahabharataДокумент9 страницA Brief Overview of The MahabharatasskashikarОценок пока нет

- Courtesans of Colonial IndiaДокумент14 страницCourtesans of Colonial IndiaMannatОценок пока нет

- Classical DanceДокумент16 страницClassical Danceরজতশুভ্র করОценок пока нет

- Everyday Creativity: Singing Goddesses in the Himalayan FoothillsОт EverandEveryday Creativity: Singing Goddesses in the Himalayan FoothillsОценок пока нет

- Classification of Ashtanayikas: RathoreДокумент63 страницыClassification of Ashtanayikas: RathoreKamal Jajoriya100% (1)

- B - A - BharathanatyamДокумент65 страницB - A - Bharathanatyamsathya90Оценок пока нет

- Anu Aneja - Feminist Theory and The Aesthetics Within - A Perspective From South Asia-Routledge India (2021)Документ220 страницAnu Aneja - Feminist Theory and The Aesthetics Within - A Perspective From South Asia-Routledge India (2021)Katerina Sergidou100% (1)

- 4) Shakespeare - Sonnet 130Документ10 страниц4) Shakespeare - Sonnet 130Reem MohamedОценок пока нет

- MA - MohiniyattamДокумент90 страницMA - MohiniyattamPriya NairОценок пока нет

- Thyagaraja Charitram-By T S Sundaresa SarmaДокумент27 страницThyagaraja Charitram-By T S Sundaresa SarmadeathesОценок пока нет

- Nuances of RasaДокумент15 страницNuances of RasaKadambari PandeyОценок пока нет

- Art Connect Vol 6 Issue 1: Issue of Art Connect, A Journal of India Foundation of The Arts, BangaloreДокумент106 страницArt Connect Vol 6 Issue 1: Issue of Art Connect, A Journal of India Foundation of The Arts, BangaloreN_Kalyan_Raman_4111Оценок пока нет

- Exploring Women's Voices and Their Writings in Bhakti MovementДокумент7 страницExploring Women's Voices and Their Writings in Bhakti MovementrahulОценок пока нет

- DanceДокумент28 страницDanceGautamОценок пока нет

- Sangam LiteratureДокумент5 страницSangam LiteratureLidwin BerchmansОценок пока нет

- Natyasastra AestheticsДокумент4 страницыNatyasastra AestheticsSimhachalam ThamaranaОценок пока нет

- Reconfigurations and Textualizations of Devadasi Repertoire in 19th-20th Century South IndiaДокумент10 страницReconfigurations and Textualizations of Devadasi Repertoire in 19th-20th Century South IndiaAri MVPDLОценок пока нет

- Devadasi System: A Historical PerspectiveДокумент19 страницDevadasi System: A Historical PerspectiveYallappa Aladakatti100% (1)

- The Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-LibreДокумент30 страницThe Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-Libresharath00Оценок пока нет

- Ancient Indian Mithila Region and Its RulersДокумент5 страницAncient Indian Mithila Region and Its RulersShree Vishnu ShastriОценок пока нет

- Tristram Shandy (Presentation)Документ2 страницыTristram Shandy (Presentation)danielyuenzxОценок пока нет

- Given To Dance FilmДокумент3 страницыGiven To Dance FilmSantosh Kumar MallikОценок пока нет

- Mirabai's Love of GodДокумент9 страницMirabai's Love of GodJatin Acharya RajrishiОценок пока нет

- Sanskrit DramaДокумент4 страницыSanskrit DramaTR119Оценок пока нет

- Cultural Elites and The Disciplining of BhavaiДокумент8 страницCultural Elites and The Disciplining of BhavaiRAGHUBALAN DURAIRAJUОценок пока нет

- Kuchipudi Dance: Workshop Angikabhinayam (Body Gesture)Документ61 страницаKuchipudi Dance: Workshop Angikabhinayam (Body Gesture)Kiranmai Bonala100% (1)

- INTRODUCING THE RELIGIOUS POETRY OF VACANASДокумент16 страницINTRODUCING THE RELIGIOUS POETRY OF VACANASNaga Raj SОценок пока нет

- Dancing in the Family: The Extraordinary Story of the First Family of Indian Classical DanceОт EverandDancing in the Family: The Extraordinary Story of the First Family of Indian Classical DanceОценок пока нет

- Contribution To Poetics and DramaturgyДокумент23 страницыContribution To Poetics and DramaturgyBalingkangОценок пока нет

- Ancient Indian Treatise on Performing ArtsДокумент19 страницAncient Indian Treatise on Performing Artsishika biswasОценок пока нет

- Kal Am PattuДокумент4 страницыKal Am PattusingingdrumОценок пока нет

- RK InterviewДокумент6 страницRK Interviewshakri78100% (4)

- Siva andДокумент17 страницSiva andshakri78Оценок пока нет

- (Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The AnnihilationДокумент5 страниц(Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The Annihilationshakri78Оценок пока нет

- AvvaiДокумент4 страницыAvvaishakri78Оценок пока нет

- DuryodhanaДокумент11 страницDuryodhanashakri78Оценок пока нет

- Games Ancient IndiaДокумент15 страницGames Ancient Indiashakri78Оценок пока нет

- Omar KhayyamДокумент2 страницыOmar Khayyamshakri78Оценок пока нет

- DantembДокумент3 страницыDantembshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Wendy Doniger: He Which Many People Regard As The Paradigmatic TextДокумент20 страницWendy Doniger: He Which Many People Regard As The Paradigmatic Textshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Indian Fables in Islamic ArtДокумент12 страницIndian Fables in Islamic Artshakri78Оценок пока нет

- AsuraДокумент3 страницыAsurashakri78Оценок пока нет

- Draupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic PerspectiveДокумент9 страницDraupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic Perspectiveshakri78Оценок пока нет

- AlvarsДокумент5 страницAlvarsshakri78Оценок пока нет

- HanumanДокумент6 страницHanumanshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Ravana TamilДокумент9 страницRavana Tamilshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Translation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's CourtДокумент8 страницTranslation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's Courtshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Akbar and TechnologyДокумент13 страницAkbar and Technologyshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Myth and Reality of Mahabharata and RamayanaДокумент5 страницMyth and Reality of Mahabharata and Ramayanashakri78100% (2)

- The Fortunes of Kalidasa in ItalyДокумент3 страницыThe Fortunes of Kalidasa in Italyshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Rome in The MahabharataДокумент4 страницыRome in The Mahabharatashakri78Оценок пока нет

- Duryodhana & Queen of ShebaДокумент2 страницыDuryodhana & Queen of Shebashakri78100% (1)

- The Raksasa Form of MarriageДокумент11 страницThe Raksasa Form of Marriageshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Oldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist WritingДокумент5 страницOldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist Writingshakri78Оценок пока нет

- Premchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke KhiladiДокумент13 страницPremchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke Khiladilastindiantango100% (1)

- KumbhMela. Mapping The Ephemeral Mega-City PDFДокумент53 страницыKumbhMela. Mapping The Ephemeral Mega-City PDFelgatomecirОценок пока нет

- Panja Pakshi SastramДокумент60 страницPanja Pakshi SastramThillaiRaj67% (3)

- St. Michael The Archangel StoryДокумент2 страницыSt. Michael The Archangel StoryQuennie Marie Daiz FranciscoОценок пока нет

- Roman Diviners Interpreted SacrificesДокумент2 страницыRoman Diviners Interpreted SacrificesjohnharnsberryОценок пока нет

- Aristotle and Maimonides On Virtue and Natural Law Jonathan JacobsДокумент32 страницыAristotle and Maimonides On Virtue and Natural Law Jonathan Jacobspruzhaner100% (1)

- A Comprehensive Annotated Book of Mormon BibliographyДокумент745 страницA Comprehensive Annotated Book of Mormon BibliographyJack Nabil IssaОценок пока нет

- Noli Me Tangere Report: A Brief SummaryДокумент40 страницNoli Me Tangere Report: A Brief SummaryV InspectorОценок пока нет

- Alain de Lille - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент7 страницAlain de Lille - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaabadurdОценок пока нет

- Art and ThelemaДокумент44 страницыArt and ThelemaAlbert PetersenОценок пока нет

- He Saved Others Sheet MusicДокумент10 страницHe Saved Others Sheet MusicJasper John LamsisОценок пока нет

- The Four CandlesДокумент11 страницThe Four CandlesPeoples' Vigilance Committee on Human rightsОценок пока нет

- Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa - Mystic, Alchemist & Occult WriterДокумент4 страницыHeinrich Cornelius Agrippa - Mystic, Alchemist & Occult Writerdemetrios2017Оценок пока нет

- Name of Schid Mother Level Schname Old Name No./Street Barangay Mun./City School Head Designation Telephone Fax Email Address Sch-Id Number Number Adress Contact NumbersДокумент55 страницName of Schid Mother Level Schname Old Name No./Street Barangay Mun./City School Head Designation Telephone Fax Email Address Sch-Id Number Number Adress Contact Numbersabby-b-tubog-3384Оценок пока нет

- KIRSOPP LAKE - The Text of The Gospel in AlexandriaДокумент11 страницKIRSOPP LAKE - The Text of The Gospel in AlexandriaJorge H. Ordóñez T.Оценок пока нет

- The Mysteries of God RevealedДокумент35 страницThe Mysteries of God RevealedMichael TuckerОценок пока нет

- Humility / PrideДокумент14 страницHumility / PrideQuotes&Anecdotes100% (1)

- Harnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodДокумент186 страницHarnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodDomenico CatalanoОценок пока нет

- THE VIKINGS' IMPACT ON IRELANDДокумент52 страницыTHE VIKINGS' IMPACT ON IRELANDrgkelly62100% (1)

- Excerpt From "The New Silk Roads" by Peter Frankopan.Документ6 страницExcerpt From "The New Silk Roads" by Peter Frankopan.OnPointRadioОценок пока нет

- While Western Christians Theorize 20 July 2007Документ17 страницWhile Western Christians Theorize 20 July 2007bassam.madany9541Оценок пока нет

- Studies About JoshuaДокумент118 страницStudies About Joshualuckypromotion2016Оценок пока нет

- 1 2 Timothy Titus PhilemonДокумент33 страницы1 2 Timothy Titus PhilemonPaul James BirchallОценок пока нет

- First Mass Debate: Homonhon or LimasawaДокумент3 страницыFirst Mass Debate: Homonhon or LimasawaPälösОценок пока нет

- The Dallas Post 09-09-2012Документ20 страницThe Dallas Post 09-09-2012The Times LeaderОценок пока нет

- 03 - MarkДокумент9 страниц03 - MarkLuis MelendezОценок пока нет

- Harmony 2 - Eb (Treble Clef) PDFДокумент61 страницаHarmony 2 - Eb (Treble Clef) PDFPedro SpallatiОценок пока нет

- The Spiritual Humanism of RadhakrishnanДокумент9 страницThe Spiritual Humanism of RadhakrishnanPradeep ThawaniОценок пока нет

- Theo 313 Completed Book ReviewДокумент5 страницTheo 313 Completed Book ReviewLiliana MejiaОценок пока нет

- Black LodgeДокумент29 страницBlack LodgeAn LingОценок пока нет

- Tarzi Akbar... Ideology of Modernization Iin AfghanistanДокумент25 страницTarzi Akbar... Ideology of Modernization Iin AfghanistanFayyaz AliОценок пока нет