Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Research and Evaluation Counseling Outcome

Загружено:

Mahesh RanaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research and Evaluation Counseling Outcome

Загружено:

Mahesh RanaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation

http://cor.sagepub.com/ Psychosocial Educational Groups for Students (PEGS) : An Evaluation of the Treatment Effectiveness of a School-Based Behavioral Intervention Program

Rebecca A. Newgent, Bonni A. Behrend, Karyl L. Lounsbery, Kristin K. Higgins and Wen-Juo Lo Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 2010 1: 80 originally published online 10 September 2010 DOI: 10.1177/2150137810373919 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cor.sagepub.com/content/1/2/80

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Association for Assessment in Counseling and Education

Additional services and information for Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cor.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cor.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://cor.sagepub.com/content/1/2/80.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Oct 29, 2010 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Sep 10, 2010

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

What is This?

Outcome-Based Program Evaluation

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2) 80-94 The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/2150137810373919 http://core.sagepub.com

Psychosocial Educational Groups for Students (PEGS): An Evaluation of the Treatment Effectiveness of a School-Based Behavioral Intervention Program

Rebecca A. Newgent,1 Bonni A. Behrend,1 Karyl L. Lounsbery,1 Kristin K. Higgins,1 and Wen-Juo Lo1

Abstract The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcome of a new psychosocial intervention program, Psychosocial Educational Groups for Students (PEGS). The PEGS program is designed to help students in the areas of social skills, problem behaviors, bullying, and self-esteem. Three groups of elementary school students participated. Results showed significant improvement in selfcontrol for Group 1; social skills for Group 2; and assertion, self-reported bully behaviors, and perception of self for Group 3. Strong effect sizes were found for many of the indicators. Implications for counselors are presented. Keywords psychosocial education, intervention, elementary school students, problem behaviors, bullying

Received 23 June 2009. Revised 6 October 2009. Accepted 2 May 2010.

Psychoeducational groups have long been used to address a variety of problems and issues within the school system (Mishna & Muskat, 2004). Groups have been used to approach social skill deficits and problem behaviors (Dennison, 2008; Savidge, Christie, Brooks, Stein, & Wolpert, 2004) and problem-solving deficits (Dore, Nelson-Zlupko, & Kaufman, 1999), to enhance learning (Carnahan, Musti-Rao, & Bailey, 2009; Dangwal & Kapur, 2009; Harris, Yuill, & Luckin, 2008), to treat depression and improve self-esteem, (Merrell, 2001) and to address bullying (Newman-Carlson & Horne, 2004). The purpose of this study was to evaluate

the outcome of a new psychosocial intervention program, Psychosocial Educational Groups for Students (PEGS). The PEGS program is designed to help elementary school students in the areas of social skills, problem behaviors, bullying, and self-esteem.

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA

Corresponding Author: Rebecca A. Newgent, 137 Graduate Education Building, Counselor Education Program, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA Email: rnewgent@uark.edu

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

81

Psychoeducational groups are often used in schools because they are a cost-effective way of teaching many children at once (Dennison, 2008). According to Kulic, Dagley, and Horne (2001), 81% of the groups in their metaanalysis were held in a school setting. Often children with behavioral or emotional problems exhibit these problems at school (Dennison, 2008). Because groups have been an effective way of teaching children in a school setting (Gerrity & DeLucia-Waack, 2007; Schectman, Bar-el, & Hadar, 1997), especially when used as a preventative measure (Shechtman, 2002), using psychoeducational groups to address problem behaviors and emotional concerns within the school setting seems appropriate.

Social Skills and Problem Behaviors

Social skills, as defined by Elksnin and Elksnin (2006), are abilities that allow an individual to perform competently in social situations (p. 4). Social skills are generally learned at home (Horne, Bartolomucci, & Newman-Carlson, 2003). Not all children, however, learn these skills or know how to identify when these skills are appropriate (Horne et al., 2003). Children who do not know basic social skills can have difficulty maintaining relationships with peers or adults (Savidge et al., 2004) are frequently rejected by peers (Elksnin & Elksnin, 2006; Horne et al., 2003) and may have mental health problems (Elksnin & Elksnin, 2006). Psychoeducational groups conducted in the schools may be beneficial in increasing social skills and decreasing problem behaviors in children who have not sufficiently developed these skills or fail to use them in appropriate situations (LeCroy, 2009). Dennison (2008) studied the outcome of nine short-term school-based social skills groups on seventy 2nd through 12th grade at-risk students. Pre- and posttest quantitative data included the Index of Peer Relations (IPR; Hudson, 1992), a self-assessment to measure the degree to which students are having problems with their peers and the Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale (BERS-2; Epstein, 2004), a teacher assessment to measure the

behavioral and emotional strengths of students in the classroom. Although the author did not provide any statistical data, Dennison reported that the direction of the BERS-2 ratings showed an increase in teachers perceptions of participants emotional and behavioral strengths, although it was nonsignificant. Bostick and Anderson (2009) evaluated a 10-week social skills deficits small-group counseling intervention program on 49 third grade elementary school students. Self-report instruments measuring loneliness and social anxiety were administered as part of the screening process and students with the lowest scores were recommended for the intervention. The intervention program implemented was the Social Skills Group Intervention (S.S.GRIN; DeRosier, 2002). Improvement was noted in levels of loneliness and social anxiety. Although the results were statistically significant and also appear clinically significant, given the magnitude of the effect sizes, they must be interpreted with caution as no control group was used in this study and no follow-up assessments were collected to assess for the long-term impact of change. Next, Muskett (2009) evaluated the impact of a social skills training intervention on a convenience sample of 12 elementary school students categorized as emotionally or behaviorally disabled. Teachers, parents, and students completed the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990a) pre- and postintervention. The intervention consisted of social skills training using childrens literature, discussion, games, direct instruction, role-playing, and homework (Muskett, 2009, p. 39). Results indicated that, contrary to what parents and teachers perceived, students perceived that they had increased social skills after the intervention (Muskett, 2009). Given the limited size of the groups and the lack of statistical data, results from this study should be interpreted with caution. Cotugno (2009) examined the impact of a S.S.GRIN on 18 students aged 7 to 11, who were diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Teachers completed the WalkerMcConnell Scale of Social Competence and Social Adjustment (WMS; Walker & McConnell, 1995) pre-

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

82

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

and post-intervention. The intervention consisted of 30 one-hr weekly sessions of stage-based, group focused competency/skills curriculum (Cotugno, 2009, p. 1270). Overall, the results of this study indicate that the stage-based competency intervention was effective for children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (Cotugno, 2009). Problem behaviors, such as disruptive behavior and aggression, have also been studied in the context of psychoeducational groups. For example, McCurdy, Lannie, and Barnabus (2009) studied the outcome of an interdependent group contingency on 600 elementary school children identified as having disruptive behavior (e.g., out of seat, play fighting, physical contact with force, throwing objects, and screaming). Results indicated that overall student levels of disruptive behaviors diminished after the implementation of the Lunchroom Behavior Game. Although the impact of this intervention appears positive, there was no assessment to measure whether the reduction in disruptive behaviors was maintained postintervention. Finally, Ostrov et al. (2009) conducted a preventive intervention for aggressive behavior in pre-kindergarten early childhood classrooms with nine classrooms in the treatment condition and nine classrooms in the control condition. The intervention program implemented included puppet shows to demonstrate particular attributes, participatory activities to reinforce behavioral skills taught to children, and concept activities designed to reinforce positive behavior. Results failed to reveal a significant effect for differences between the intervention and control conditions on relational aggression, physical aggression, or prosocial behavior (Ostrov et al., 2009). However, given that the unit of analysis was the classroom (and not the student), the analysis may be underpowered for finding significant differences. Published empirical studies on social skills and problem behaviors intervention groups conducted in elementary schools are very limited (LeCroy, 2009). The majority lack sufficient sample size and fail to report statistical data. Many are unclear on the methods and procedures used. Overall, the generalizability of the results of these studies is limited. Needed

are studies that have strong research design and sound statistical analysis of the impact of interventions on childrens social skills and problem behaviors over time.

Self-Esteem and Bullying

Part of preventing problem behaviors, including bullying in school, is increasing the self-esteem of those with problem behaviors. Olweus (1991) defined bullying as someone who is exposed, repeatedly, and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more persons (p. 413). Olweus (1997) later added that bullying included an imbalance of power (an asymmetric power relationship) (p. 496). With this addition, his definition now included three components to bullying; that it is purposeful behavior, repeated over time, and includes an imbalance of power (Olweus, 1997). Having positive or high self-esteem is crucial to childrens ability to make constructive life choices (Kenny & McEachern, 2009). Self-esteem, also called self-worth, is defined as a childs global concept of themselves (Kistner, David, & Repper, 2007) and considered critical for school-aged childrens health (Delgas-Pelish, 2006) and academic competence (Ferkany, 2008). Children who are often the victims of bullies may lack self-esteem. Programs designed to foster or enhance childrens self-esteem may be helpful in reducing incidences of peer victimization (bullying). Few studies, however, actually exist that empirically explore the effectiveness of psychosocial educational groups for victims of bullying and/or low self-esteem. The majority of studies on this population are surveys. For example, OMoore and Kirkham (2001) examined data from a nationwide (Ireland) survey of bullying behavior in 8,249 school-aged children. Students completed a modified version of the Olweus Self-Report Questionnaire on school bullying (Whitney & Smith, 1993) and the Piers-Harris Self-concept Scale (Piers, 1984) on how children feel about themselves (self-esteem). Results showed that high levels of self-esteem were identified as a protective factor from involvement in bullying (OMoore & Kirkham, 2001).

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

83

Next, DeRosier (2004) studied the outcome of a school-based social skills intervention group on 187 third grade students. Evaluation of student peer liking, aggression/bullying, and victimization were conducted. The intervention program implemented was the S.S.GRIN (DeRosier, 2002). The results revealed that social skills training was beneficial in helping children with confidence, relationships, and social situation (DeRosier, 2002). Jenson and Dieterich (2007) studied the outcome of a school-based intervention program designed to inhibit bullying and victimization on 462 fourth grade students. Assessment data were collected at four time points via the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire for Students (Olweus, 1996). Results showed that the program appears to have reduced levels of victimization while not having an impact on levels of bullying (Jenson & Dieterich, 2007). Finally, Jankauskiene, Kardelis, Sukys, and Kardeliene (2008) examined the association between school bullying and psychosocial factors in 1,162 students in the 6th, 8th, and 11th grades. Results showed that students involved in bullying were more unhappy than happy and had lower self-esteem (Jankauskiene et al., 2008). Results indicated that there appears to be a link between bullying and/or victimization and reduced self-esteem. Although these findings may establish the aforementioned link, the study only used self-report data, which limited the authors ability to verify the results with other sources. There are many programs that have been developed both at the national and international levels that have purported to target bullying behavior and support victims of bullies by increasing self-esteem (i.e., DeRosier, 2004; DeRosier & Marcus, 2005; Fox & Boulton, 2003; Hall, 2006; Horne, Orpinas, NewmanCarlson, & Bartolomucci, 2004; Orpinas, Horne, & Staniszewski, 2003; Smith, Schneider, Smith, & Ananiadou, 2004). Few of these studies, however, provide sufficient evidence to empirically support the use of such programs and results are often mixed. In addition, while many of these studies look at increasing teacher and school-wide use of anti-bullying prevention

strategies, none of the studies look specifically at the effectiveness of small psychoeducational groups to help student victims of bullies who lack self-esteem. Overall, the above studies reported on the outcome of psychoeducational groups to improve students lives. Pyschoeducational programming has a long history as an effective type of intervention in the schools. It is useful in addressing a variety of issues that students face on a regular basis and can easily augment services that are already in place. The purpose of the PEGS program is to provide additional educational opportunities to students who would benefit from information about how to get along better with their peers and to feel better about themselves. Furthermore, the PEGS program is intended to be a short-term, nonintrusive, and nonstigmatizing intervention where referrals are based on observed behaviors and not specific labels. This study aims to assess the impact of a selective intervention on measures of social skills, problem behaviors, teacher- and selfreports of peer relationships (bullying behaviors and peer victimization), self-esteem (self-worth, ability, self-satisfaction, and selfrespect), and perception of self. The following research question was tested: Does the PEGS program have a positive impact on measures of social skills, problem behaviors, peer relationships, and self-esteem in the short- and long-term?

Method Participants

Thirty-one (N 31) students were enrolled in the PEGS program, 29 students completed the program, and there were 28 students at the time of the follow-up assessment. Of the original participants, 19 (61.3%) were male and 12 (38.7%) were female. Eleven students (35.5%) were in 3rd grade, seven students (22.6%) were in 4th grade, and 13 students (41.9%) were in 5th grade. Twenty-three students (74.2%) identified as White, seven students (22.6%) identified as African American, and one student (3.2%)

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

84

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

identified as Hispanic. Additionally, six students (19.4%) were identified as having some type of disability (i.e., learning, behavioral, and emotional). Selective Intervention Program One of the underlying tenets of the PEGS program is that students should not be labeled or stigmatized for having problems. Therefore, the PEGS program used referrals that were based on underlying characteristics that lead to specific problems, not labels (i.e., ADHD, ODD, etc.). Thus, students who are impulsive, depressed, dominant, lonely, easily frustrated, anxious, lack empathy, have low self-esteem, have difficulty following rules, are socially withdrawn, view violence in a positive way, have few friends, make negative attributions, have mood swings, instigate conflict, have difficulty handling conflict, or are aggressive or stressed were identified by their teachers and recommended for the PEGS program. PEGS provides a series of six hr group sessions over the course of 6 weeks for elementary school students in grades 35. The six psychosocial education components (and their associated objective) of the PEGS program are (a) improving social skillsa lesson on cooperation, (b) building and increasing selfesteema lesson that encourages students to be proud of who they are, (c) developing problem-solving skillsto learn the STAR model of how to stop, think, act, and review, (d) assertiveness traininga lesson about breaking the chain of violence using puppets to play the part of the victim, (e) enhancing stress/coping skillsa lesson about handling anxiety and stress using puppets to play the part of the student, and (f) prevention of mental health problems/problem behaviorsa lesson on the importance of tolerance using puppets to model acceptance of commonalities and differences. Lessons were adapted from Lively Lessons for Classroom Sessions (Sartori, 2000), More Lively Lessons for Classroom Sessions (Sartori, 2004), and Acting Assertively (Hess, 1999). Students were divided into three groups based on their pre-assessment scores. Group 1

students had primarily clinically elevated behavioral problems and poor social skills. That is, a majority of the students identified for Group 1 had percentile scores ! 84 on the behavioral problems scale and 16 on the social skills scale of the Social Skills Rating ScaleTeacher Form (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990b). Group 2 students had primarily poor social skills. That is, a majority of the students identified for Group 2 had low percentile scores on the social skills scale of the SSRS (Gresham & Elliott, 1990b). Group 3 students had no clinically significant issues. That is, a majority of the students identified for Group 3 had scores that fell within the normal range. Teachers, however, thought that the students might benefit from the group making it more of a preventive psychoeducational group than an intervention for this group. No control group was used in this study at the schools request. School administrators were interested in ensuring that all students identified for services by their teachers actually received services and delaying treatment for one group was not feasible, given the timing of the academic year. They also indicated that given the time commitment of completing all assessments, teachers might not be willing to participate, if their students were not actually receiving services. Given that we were assessing change within groups over time and not differences between groups, we agreed to the schools request. Instruments SSRS. The SSRS was developed by Gresham and Elliott (1990b) and published by the American Guidance Service, Inc. It is designed to measure students social skills, problem behaviors, and academic competence. The SSRS-T is a 57-item rating scale designed specifically for teachers to use to assess childrens schoolrelated problem behaviors and competencies. Scores reported for each of the three measurement areas are percentiles. Clinical levels for each of the three areas are as follows: social skills ( 16), problem behaviors (!84), and academic competence ( 16). For the purposes of this study, only social skills and problem

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

85

behaviors were evaluated. Cronbach alphas for social skills were .89, .92, and .94 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for problem behaviors were .78, .86, and .83 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively. Peer Relationship MeasureTeacher Report. The Peer Relationship MeasureTeacher Report (Newgent, 2008a) was developed specifically for the PEGS program. It measures teachers perceptions about peer victimization. Eight items measure bullying behaviors and eight items measure victimization. Items are scored as 0 never, 1 sometimes, and 2 a lot, with scores ranging from 0 to 16 for each area. Scores reported for both of the measurement areas are totals. A high score indicates a high level of bullying behaviors and/or victimization; a low score indicates a low level of bully behaviors and/or victimization. Cronbach alphas for bullying behaviors were .86, .81, and .85 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for victimization were .81, .80, and .81 at pre-, post-, and followup assessment, respectively. Peer Relationship MeasureSelf Report. The Peer Relationship MeasureSelf Report (Newgent, 2008b) was developed specifically for the PEGS program. It measures students perceptions about peer victimization. Eight items measure bullying behaviors and eight items measure victimization. Items are scored as 0 never, 1 sometimes, and 2 a lot, with scores ranging from 0 to 16 for each area. Scores reported for both of the measurement areas are totals. A high score indicates a high level of bullying behaviors and/or victimization; a low score indicates a low level of bullying behaviors and/or victimization. This measure is a parallel measure to the Peer Relationship MeasureTeacher Report. Cronbach alphas for bullying behaviors were .66, .72, and .79 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively. Cronbach alphas for victimization were .77, .67, and .87 at pre-, post-, and followup assessment, respectively.

Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (a). The Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (a; Zimprich, Perren, & Hornung, 2005) measures an individuals level of self-esteem (i.e., perception of self-worth, ability, selfsatisfaction, and self-respect). The 10-item inventory uses a 4-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree somewhat, disagree somewhat, and strongly disagree). Five of the items are reverse coded and the score reported is the total, which ranges from 0 to 30. A high score indicates a high level of self-esteem; a low score indicates a low level of self-esteem. Students completed this inventory. Cronbach alphas were .47, .78, and .88 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively. Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (b). The Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (b; Zimprich et al., 2005) measures an individuals self-esteem (i.e., perception of self). The 4-item inventory uses a 5-point Likert-type scale (never, seldom, sometimes, often, and always). One of the items is reverse coded and the score reported is the total, which ranges from 4 to 20. A high score indicates a high level of self-esteem; a low score indicates a low level of self-esteem. Students completed this inventory. Cronbach alphas were .53, .69, and .70 at pre-, post-, and follow-up assessment, respectively.

Procedure

Thirty-two students were recommended by their teachers for the Program and 31 parental consents/child assents were received. Recommending teachers completed the SSRS-Teacher Form (Gresham & Elliott, 1990b) and the Peer Relationship MeasureTeacher Report (Newgent, 2008a) prior to the start of the PEGS program, 2 weeks after the conclusion of the PEGS program, and at 2 months after the conclusion of the PEGS program. Ideally, we would have liked a longer follow-up period than 2 months, however; we needed to work within the time constraints of the schools academic calendar. Students completed the Peer Relationship MeasureSelf Report (Newgent, 2008b),

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

86

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

the Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (a; Zimprich et al., 2005), and the Modified Rosenbergs Self-Esteem Inventory (b; Zimprich et al., 2005) prior to the start of the PEGS program, 2 weeks after the conclusion of the PEGS Program and at 2 months after the conclusion of the PEGS program. All participating students received a certificate of completion at the conclusion of the last session. Sessions were co-facilitated by four graduate students in the counseling or educational research programs. All facilitators passed criminal background checks and had prior professional experience working with children who exhibited problematic behaviors. Facilitators continuously updated each other on the progress of their groups and made suggestions so as to keep all sessions between groups as uniform as possible. Supervision was provided to the facilitators by two counseling faculty members overseeing the program. Data Analytic Plan Each student who participated in the PEGS program was assessed at three time points using a variety of measurement instruments (see Instruments section). Scores on each of the instruments were analyzed using a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), repeated measures design to assess for a significant overall effect and treatment effect between the pretest assessment and the posttest assessment, between the pretest assessment and the follow-up assessment, and between the posttest assessment and the follow-up assessment for each group. Effect sizes are reported as small !.02, medium !.13, and large !.26 (see Steyn & Ellis, 2010). A series of t tests were also conducted as follow-up tests to evaluate the pairwise differences among the means when there was a significant overall effect. The alpha was set at .017 (.05/3 .017) to control for Type I error over the three pairwise comparisons.

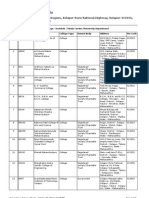

1 are displayed in Table 1. Results for the subscale of self-control revealed a significant effect for the treatment, Wilks L .18, F(2, 6) 13.41, p .006. The multivariate effect size Z2 .82 indicates a very strong relationship between teacher-reported self-control and the treatment. Results of the pairwise t-tests indicate that there was a statistically significant improvement in self-control from the pretest to the posttest, t(7) 3.27, p .01 and from the pretest to the follow-up test, t(7) 4.94, p .002. No other significant results were found for Group 1. Group 2 Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, repeated measures design. Mean scores across the trials, power, and effect size for Group 2 are displayed in Table 2. Results analyzing the social skills scale revealed a significant effect for the treatment, Wilks L .43, F(2, 8) 5.28, p .03. The multivariate effect size Z2 .57 indicates a very strong relationship between teacher-reported social skills and the treatment. Results of the pairwise t tests failed to reveal statistically significant improvement in social skills from the pretest to the posttest, t(9) 2.62, p .03, from the pretest to the follow-up test, t(9) 2.26, p .05, and from the posttest to the follow-up test, t(9) 0.19, p .86. No other significant results were found for Group 2. Group 3 Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, repeated measures design. Mean scores across the trials, power, and effect size for Group 3 are displayed in Table 3. Results for the subscale of assertion revealed a significant effect for the treatment, Wilks L .36, F(2, 8) 7.13, p .02. The multivariate effect size Z2 .64 indicates a very strong relationship between teacher-reported assertion and the treatment. Results of the pairwise t tests revealed a statistically significant improvement in assertion from the posttest to the follow-up test, t(9) 3.27, p .01. Results failed to reveal statistically significant improvement from the pretest to the posttest, t(10) 2.38, p .04 and from the pretest to the follow-up test, t(9) 0.53, p .61. Results analyzing self-reported bully

Results

Group 1 Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, repeated measures design (a statistical procedure used to measure growth). Mean scores across the trials, power, and effect size for Group

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

87

Table 1. Mean Pre-, Post-, and Follow-Up Test Comparisons of the Impact of the PEGS ProgramGroup 1 M (SD) Assessment Instrument Teacher-reported SSRSSocial skill Cooperation Assertion Self-control SSRSProblem behaviors Externalizing Internalizing Hyperactivity Bully behaviors Peer victimization Self-reported Bully behaviors Peer victimization Self-esteem Perception of self Pretest Posttest Follow-Up 28.00 (26.79) 11.13 (3.94) 11.00 (4.81) 10.50 (3.96) 83.25 (12.36) 5.75 (2.32) 4.50 (3.30) 6.75 (2.12) 6.63 (4.37) 5.25 (4.13) 2.13 (2.30) 3.63 (3.82) 20.50 (7.87) 14.63 (4.63) Repeated Measures ANOVA Wilkss L .60 .60 .54 .18 .58 .45 .96 .60 .65 .89 .93 .78 .74 .93 F(df) 2.06 (2,6) 2.09 (2,6) 2.55 (2,6) 13.41 (2,6) 2.20 (2,6) 3.68 (2,6) .13 (2,6) 1.99 (2,6) 1.61 (2,6) .36 (2,6) .24 (2,6) .85 (2,6) 1.05 (2,6) .22 (2,6) p .21 .21 .16 .006 .19 .09 .88 .22 .28 .72 .79 .47 .41 .81 Multivariate Z2 .41 .41 .46 .82 .42 .55 .04 .40 .35 .11 .08 .22 .26 .07

10.00 (4.81) 17.13 (14.78) 8.50 (5.43) 9.00 (3.46) 10.13 (2.85) 10.00 (4.00) 6.25 (3.66) 9.00 (3.93) 92.38 (4.44) 88.38 (11.94) 7.63 (3.11) 4.13 (2.17) 8.75 (3.41) 7.50 (4.57) 4.63 (3.99) 6.63 4.62 8.50 5.38 4.50 (3.46) (2.72) (3.43) (3.79) (2.98)

1.75 (2.61) 1.63 (1.51) 3.75 (2.71) 4.63 (3.11) 17.50 (4.00) 19.63 (7.46) 14.50 (3.96) 13.63 (6.02)

behaviors revealed a significant effect for the treatment, Wilks L .42, F(2, 8) 5.44, p .03. The multivariate effect size Z2 .58 indicates a very strong relationship between selfreported bullying behaviors and the treatment. Results of the pairwise t tests revealed statistically significant improvement in self-reported bullying behaviors from the pre-test to the follow-up test, t(9) 3.34, p .009. Results failed to reveal statistically significant improvement from the pretest to the posttest, t(10) 1.94, p .08 and from the posttest to the follow-up test, t(9) 2.69, p .03. Results analyzing self-reported perception of self revealed a significant effect for the treatment, Wilks L .44, F(2, 8) 5.19, p .04. The multivariate effect size Z2 .57 indicates a very strong relationship between self-reported perception of self and the treatment. Results of the pairwise t tests failed to reveal statistically significant improvement in self-reported perception of self from the pretest to the posttest, t(10) 2.03, p .07, from the pretest to the follow-up test, t(9) 1.41, p .19, and from the posttest to the follow-up test, t(9) .57, p .58. No other significant results were found for Group 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of a selective intervention on measures of social skills, problem behaviors, teacher- and self-reports of peer relationships (bullying behaviors and peer victimization), self-esteem (self-worth, ability, self-satisfaction, and selfrespect), and perception of self in elementary school students. The PEGS program was designed to be a short-term, nonstigmatizing program that can easily augment current school counselor services. Three groups of students, with differing presenting issues, received the intervention. A discussion of the impact for each of the three groups follows.

Group 1

Students in Cohort 1 initially scored in the clinical range on social skills and problem behaviors. Findings indicated that the PEGS program had a significant overall effect on the teacher-reported social skills subscale of selfcontrol and a significant treatment effect between the pretest and the posttest and between

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

88

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

Table 2. Mean Pre-, Post-, and Follow-Up Test Comparisons of the Impact of the PEGS ProgramGroup 2 M (SD) Assessment Instrument Pretest Posttest Follow-Up Repeated Measures ANOVA Wilkss L .43 .71 .71 .68 .89 .87 .62 .69 .75 .74 .67 .88 .98 .83 F(df) 5.28 (2,8) 1.65 (2,8) 1.63 (2,8) 1.88 (2,8) .51 (2,8) .60 (2,8) 2.44 (2,8) 1.79 (2,8) 1.35 (2,8) 1.39 (2,8) 1.93 (2,8) .53 (2,8) .07 (2,8) .83 (2,8) p .03 .25 .26 .21 .62 .57 .15 .23 .31 .30 .21 .61 .94 .47 Multivariate Z2 .57 .29 .29 .32 .11 .13 .38 .31 .25 .26 .33 .12 .02 .17

Teacher-reported SSRSSocial skill 17.20 (9.60) 29.30 (22.56) 30.70 (21.98) Cooperation 10.40 (3.17) 10.60 (2.12) 12.30 (2.79) Assertion 7.50 (3.92) 9.50 (5.08) 8.90 (5.57) Self-control 8.50 (3.27) 9.60 (4.60) 9.80 (4.10) SSRSProblem 73.00 (22.98) 69.30 (26.51) 75.10 (20.59) behaviors Externalizing 5.40 (2.91) 6.20 (3.68) 5.00 (2.75) Internalizing 5.80 (3.94) 4.70 (3.80) 5.80 (3.05) Hyperactivity 5.40 (3.47) 4.60 (2.80) 5.40 (3.03) Bully behaviors 5.30 (3.47) 4.20 (3.26) 5.20 (2.82) Peer victimization 5.50 (3.38) 4.40 (3.24) 4.60 (7.80) Self-reported Bully behaviors 2.80 (2.25) Peer victimization 6.40 (2.50) Self-esteem 20.30 (4.08) Perception of self 15.20 (3.68) 3.50 (3.21) 6.00 (2.67) 21.10 (5.71) 15.20 (4.34) 4.00 (3.30) 7.20 (4.49) 20.80 (8.30) 13.70 (4.47)

the pretest and the follow-up test. This result suggests that students with deficits in selfcontrol benefited from the PEGS program. That is, there was an increase in self-control for students who participated in the psychoeducational groups. These results are consistent with the literature (see Dennison, 2008; Savidge et al., 2004). If we take into account effect size, several teacher-reported measures (social skills, cooperation, assertion, self-control, problem behaviors, externalizing, hyperactivity, and bullying behaviors) show strong relationships (multivariate effect size Z2 ! .26) between the measures and the treatment. Additionally, there was a strong relationship between self-reported self-esteem and the treatment. Therefore, the lack of statistical significance was likely due to the lack of power associated with the small sample size. There are several implications of the PEGS program on student behavior in Group 1. For example, students are more likely to have improved performance in social situations. That is, they would be more likely to be able to maintain relationships longer (Savidge et al., 2004) and may not be as likely to be shunned by their peers. Students may also report fewer instances

of loneliness as increases in social skills can also lead to increases in self-confidence (Bostick & Anderson, 2009). Teachers might be more likely to notice that these students can control their temper better in conflict situations with peers and respond more appropriately when pushed or hit by other children. Finally, noted changes in the classroom and school should include a greater sense of belonging as these students have improved social skills, which may lead to other students including them in play, group assignments, and lunch.

Group 2

Students in Group 2 initially scored in the clinical range on social skills. Findings indicated that the PEGS program had a significant overall effect on teacher-reported social skills, however, there was no significant treatment effect on any pairwise comparisons. Thus, the primary problem initially presented by these students was affected positively. If we take into account effect size, several teacher-reported measures (social skills, cooperation, assertion, self-control, internalizing, hyperactivity, and

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

89

Table 3. Mean Pre-, Post-, and Follow-Up Test Comparisons of the Impact of the PEGS ProgramGroup 3 M (SD) Assessment Instrument Teacher-reported SSRSSocial skill Cooperation Assertion Self-control SSRSProblem behaviors Externalizing Internalizing Hyperactivity Bully behaviors Peer victimization Self-reported Bully behaviors Peer victimization Self-esteem Perception of self Pretest 54.70 (22.33) 13.40 (5.91) 13.90 (3.38) 15.00 (3.33) 54.90 (24.36) 1.80 (1.93) 4.20 (3.58) 3.90 (3.67) 2.00 (1.89) 1.80 (1.99) 2.00 (1.49) 5.30 (2.87) 22.00 (2.31) 14.70 (2.16) Posttest 53.60 14.30 11.70 15.00 50.50 (29.37) (4.27) (4.57) (3.80) 29.07) Follow-Up 63.30 15.40 14.60 14.60 55.00 2.70 3.10 4.50 1.50 2.60 .80 3.90 24.00 16.20 (29.89) (5.40) (5.17) (4.90) (25.77) (2.06) (3.25) (4.30) (1.90) (2.84) (0.92) (2.92) (6.46) (4.34) Repeated Measures ANOVA Wilkss L .75 .49 .36 .98 .90 .85 .88 .88 .78 .66 .42 .71 .84 .44 F(df) 1.37 (2,8) 4.23 (2,8) 7.13 (2,8) .10 (2,8) .46 (2,8) .72 (2,8) .56 (2,8) .53 (2,8) 1.13 (2,8) 2.02 (2,8) 5.44 (2,8) 1.65 (2,8) .79 (2,8) 5.19 (2,8) p .31 .06 .02 .91 .65 .52 .59 .61 .37 .19 .03 .25 .49 .04 Multivariate Z2 .26 .51 .64 .03 .10 .15 .12 .12 .22 .34 .58 .29 .16 .57

2.50 (2.51) 3.10 (2.33) 4.00 (3.89) 1.50 (2.17) .90 (0.99) 1.50 4.20 23.90 16.60 (1.28) (2.25) (4.73) (2.72)

peer victimization) show strong relationships (multivariate effect size Z2 ! .26) between the measures and the treatment. Additionally, there was a strong negative relationship between self-reported bully behaviors and the treatment. Again, the lack of statistical significance was likely due to the lack of power associated with the small sample size. One possible implication of these results is that these students may have had problems with bullying behaviors that had been masked by or attributed to their social skills deficits. As such, students in this group might benefit from more focused intervention related to peer victimization (e.g., Bully Busters, Horne et al., 2003). Changes that teachers should notice include students responding more appropriately to peer pressure and more frequently initiating conversation with their peers. However, teachers should also notice that when these same students attempt to be more social they often do so in a manner that may invite bullying or in a manner that could be perceived as aggressive given, they are not yet adept in the social skills arena.

Group 3

Students in Group 3 had no scores in the clinical range at the pretest assessment. Findings indicated that the PEGS program had a significant overall effect on the teacher-reported social skills subscale of assertion and self-reported bully behaviors and perception of self. Significant treatment effects were found between the pretest and the follow-up tests for assertion and self-reported bully behaviors. However, there was no significant treatment effect on the pairwise comparisons for self-reported perception of self. These results suggest that students without clinically significant problems benefited from the PEGS program. Once again, if we take into account effect size, several teacher-reported measures (social skills, cooperation, assertion, and peer victimization) show strong relationships (multivariate effect size Z2 ! .26) between the measures and the treatment. Additionally, there was a strong relationship between self-reported bully behaviors and peer victimization and selfreported perception of self and the treatment. Thus, the lack of statistical significance was

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

90

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

again likely due to the lack of power associated with the small sample size. The PEGS program appeared to reinforce these students abilities to handle problems with peers, thereby fostering their selfconfidence in their abilities. These abilities can act as a protective or preventative factor, consistent with the work of Shechtman (2002), for problem development. Implications for this group include enhanced abilities to cope with changes, which may increase their potential for academic success (Bostic & Anderson, 2009; Shechtman, 2002). Furthermore, teachers should notice that students initiate conversations more with their peers and make friends easier. These findings support the use of whole classroom wide guidance to serve the needs of all students, regardless of skill or functioning level.

children whose test results initially indicated no clinical deficits also showed improvement. As the realm of education places more emphasis on academic accountability and transparent data, more data-driven research in regard to outcome measures is needed in the field of counseling. The PEGS program is one that produces effective outcome results (based on effect size interpretation) that can be used immediately by counselors as well as teachers. Additionally, each lesson is easily presented and minimal training would be needed to have school counselors, school-based counselors, teachers, and even volunteer parents facilitate the sessions.

Limitations and Future Directions

There were some limitations to this study. First, the small sample sizes within groups, while helpful in group management, most likely reduced the measurable impact of the program (i.e., power). That is, while clinically meaningful differences exist (multivariate effect size Z2 ! .26) they are not statistically significant given the limited power (Cohen, 1992); however, they may be practically significant (LeCroy & Krysik, 2007). Additionally, the small sample size limits generalizability of the results as statistical power is reduced. Although we were not particularly looking for differences between groups, we did know that there were initial differences between groups as their group assignment was based on pretest assessment scores. Second, we did not have the opportunity to use a control group (no treatment group). Therefore, we were unable to determine whether the program itself made the differences found in this study. A more robust study would use both an experimental group and a control group. Finally, given the limited size of each of the groups and the overall number of participants, it was not possible to assess for the impact of cultural differences or differences based on disability status.

Conclusions

As described earlier, a wide range of research exists on psychosocial educational groups and their variety of uses within the school system. As social and emotional issues become increasingly prevalent, more research is needed on treatments that are effective, noninvasive, and time and cost efficient. In this study, the PEGS program data showed that some differences were made within the groups with minimal time, effort, and cost incurred to the school. Although the majority of the results were not statistically significant, many positive differences did occur in support of the purpose of the PEGS program, which was to provide additional educational opportunities to students who would benefit from information about how to get along better with their peers and to increase their self-worth. The results from this study extend the body of literature on group work in elementary schools. That is, in addition to supporting prior research in this area (i.e., Bostic & Anderson, 2009; Horne et al., 2003; Savidge et al., 2004; Shechtman, 2002), we found that school-based psychoeducational groups can be used for both intervention and prevention purposes. Children whose test results initially indicated clinical deficits showed improvement and

Ethical Considerations and Practice Implications

When providing counseling and educational services to children, it is important to ensure

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

91

that their best interest is taken into consideration. For example, children are not able to give consent to receiving counseling services and they are not always able to choose who else might participate in a counseling group. Accordingly, the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (ACA, 2005) provides guidance in this area. When counseling minors or persons unable to give voluntary consent, counselors seek the assent of clients to services and include them in decision making as appropriate (ACA, 2005, p. 4). In this study, in addition to securing parental consent, we also secured child assent. The ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2005) also states that Counselors screen prospective group counseling/ therapy participants. To the extent possible, counselors select members whose needs and goals are compatible with goals of the group . . . (p. 5). In addition to securing recommendations from the students teachers, we used pretest assessment results to help delineate which students should be grouped together. The ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2005) also addresses issues such as professional responsibility and research and publication. Counselors advocate to promote change at the individual, group, institutional, and societal levels that improve the quality of life for individual and groups and remove potential barriers to the provision or access of appropriate services being offered (ACA, 2005, p. 9). This aspirational statement was used to guide the development and implementation of the PEGS program. First, we believe that the services we provided would help improve students ability to engage with their peers and promote increased self-esteem, thus promoting change and improving the quality of life. Second, we believe that we developed a program that was easily accessible to students, as we provided the PEGS program to students at their schools during the school day. Finally, Counselors take reasonable measures to honor all commitments to research participants (ACA, 2005, p. 17). Prior to the implementation of the PEGS program, we provided a detailed outline of our program to the school, including what the students and school personnel could expect. We believe that we honored all our commitments to

both the students and school personnel. Overall, the PEGS programs psychosocial educational groups appeared to have a meaningful impact on the students and we encourage counselors to work with school systems to augment services to students in need and continue to extend the body of literature on group work in elementary schools. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was supported in part by research incentive funds from the College of Education and Health Professions, University of Arkansas. References

American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org Bostick, D., & Anderson, R. (2009). Evaluating a small-group counseling program: A model for program planning and improvement in the elementary setting. Professional School Counseling, 12, 428433. Retrieved from http://www.school counselor.org/content.asp?pl325&sl132& contentid235 Carnahan, C., Musti-Rao, S., & Bailey, J. (2009). Promoting active engagement in small group learning experiences for students with Autism and significant learning needs. Education and Treatment of Children, 32, 3761. doi:10.13531etc.0.0047. Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155159. doi:10.1037/00332909. 112.1.155. Cotugno, A. J. (2009). Social competence and social skills training and intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 12681277. doi:10.1007/s1080300907414. Dangwal, R., & Kapur, P. (2009). Learning through teaching: Peer-mediated instruction in minimally

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

92

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

invasive education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40, 522. doi:10.1111/ j.14678535.2008.00836.x. Delgas-Pelish, P. (2006). Effects of a self-esteem intervention program on school-age children. Pediatric Nursing, 32, 341348. Retrieved from http://www.pediatricnursing.net Dennison, S. (2008). Measuring the treatment outcomes of short-term school-based social skills groups. Social Work with Groups, 31, 307328. doi:10.1080/01609510801981219. DeRosier, M. E. (2002). Group interventions and exercises for enhancing childrens communication, cooperation, and confidence. Sarasota, NY: Professional Resources Press. DeRosier, M. E. (2004). Building relationships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of a schoolbased social skills group intervention. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 196201. Retrieved from http://www .clinicalchildpsychology.org/journal/ DeRosier, M. E., & Marcus, S. R. (2005). Building friendships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of S.S.GRIN at one-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 140150. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_13. Dore, M. M., Nelson-Zlupko, L., & Kaufman, E. (1999). Friends in need: Designing and implementing a psychoeducational group for school children from drug-involved families. Social Work, 44, 179190. Retrieved from http://puck. naswpressonline.org Elksnin, L. K., & Elksnin, N. (2006). Teaching social-emotional skills at school and home. Denver, CO: Love Publishing. Epstein, M. (2004). Behavioral and emotional rating scale-second edition. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Ferkany, M. (2008). The educational importance of self-esteem. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 42, 119132. doi:10.1111/j.14679752. 2008.00610.x. Fox, C. L., & Boulton, M. J. (2003). Evaluating the effectiveness of a social skills training (SST) programme for victims of bullying. Educational Research, 45, 231247. doi:10.1080/0013188032000137238. Gerrity, D. A., & DeLucia-Waack, J. L. (2007). Effectiveness of groups in the schools. The

Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 32, 97106. doi:10.1080/01933920600978604. Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990a). Social skills rating system. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc. Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (1990b). Social skills questionnaireTeacher form elementary level. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson, Inc. Hall, K. R. (2006). Solving problems together: A psychoeducational group model for victims of bullies. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 31, 201217. doi:10.1080/01933920600777790. Harris, A., Yuill, N., & Luckin, R. (2008). The influence of context-specific and dispositional achievement goals on childrens paired collaborative interaction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 355374. doi:10.1348/000709907X267067. Hess, L. L. (1999). Acting assertively. Warminster, PA: MAR-CO Products, Inc. Horne, A. M., Bartolomucci, C. L., & Newman-Carlson, D. (2003). Bully busters: A teachers manual for helping bullies, victims, and bystanders. Champaign, IL: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc. Horne, A. M., Orpinas, P., Newman-Carlson, D., & Bartolomucci, C. L. (2004). Elementary school bully busters program: Understanding why children bully and what to do about it. In D. Espelage & S. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 297325). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Hudson, W. (1992). Index of peer relations. Tempe, AZ: WALMYR Publishing. Jankauskiene, R., Kardelis, K., Sukys, S., & Kardeliene, L. (2008). Associations between school bullying and psychosocial factors. Social Behavior and Personality, 36(2), 145162. doi:10.2224/sbp.2008.36.2.145. Jenson, J. M., & Dieterich, W. A. (2007). Effects of a skills-based prevention program on bullying and bully victimization among elementary school children. Prevention Science, 8, 285296. doi:10.1007/ s11121-007-0076-3. Kenny, M. C., & McEachern, A. (2009). Childrens self-concept: A multicultural comparison. Professional School Counseling, 12, 207212. Retrieved from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/ content.asp?pl325&sl132&contentid235

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Newgent et al.

93

Kistner, J., David, C., & Repper, K. (2007). Selfenhancement of peer acceptance: Implications for childrens self-worth and interpersonal functioning. Social Development, 16, 2444. doi:10.1111/ j.1467-9507.2007.00370.x. Kulic, K. R., Dagley, J. C., & Horne, A. M. (2001). Prevention groups with children and adolescents. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 26, 211218. doi:10.1080/01933920108414212. LeCroy, C. W. (2009). Social skills training through groups in schools. In C. Massat, R. Constable, S. McDonald, & J. Flynn (Eds.), School social work: Practice, policy, and research (7th ed., pp. 621637). Chicago, IL: Lyceum Books. LeCroy, C. W., & Krysik, J. (2007). Understanding and interpreting effect size measures. Social Work Research, 31, 223248. McCurdy, B. L., Lannie, A. L., & Barnabas, E. (2009). Reducing disruptive behavior in an urban school cafeteria: An extension of the Good Behavior Game. Journal of School Psychology, 47, 3954. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2008.09.003. Merrell, K. W. (2001). Preventing kids with depression, anxiety from slipping through the cracks. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 17, 17. Retrieved from http:// www3.interscience.wiley.com Mishna, F., & Muskat, B. (2004). School-based group treatment for students with learning disabilities: A collaborative approach. Children and Schools, 26, 135150. Retrieved from http:// www.naswpress.org Muskett, D. P. (2009). A study of the impact of social skills training incorporating cognitive behavioral interventions in the framework of the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People on elementary students with emotional/behavioral disturbances (Doctoral dissertation, Cardinal Stritch University). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (Accession No. 200999130314). Newgent, R. A. (2008a). The peer relationship measureTeacher report. Unpublished Assessment, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Newgent, R. A. (2008b). The peer relationship measureSelf report. Unpublished Assessment, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Newman-Carlson, D., & Horne, A. M. (2004). Bully busters: A psychoeducational intervention for

reducing bullying behavior in middle school students. Journal of Counseling and Development, 82, 259267. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org Olweus, D. (1991). Bully/victim problems among school children: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. In D. Pepler & K. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 411448). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. doi:10.1111/ j.1467-9507.1995.tb00066.x. Olweus, D. (1996). The revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire for students. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen. Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and interventions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12, 495510. Retrieved from http://www.ispa.pt/ejpe/ OMoore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 269283. doi:10. 1002/ab.1010. Orpinas, P., Horne, A. M., & Staniszewski, D. (2003). School bullying: Changing the problem by changing the school. School Psychology Review, 32, 431444. Retrieved from http:// www.nasponline.org Ostrov, J. M., Massetti, G. M., Stauffacher, K., Godleski, S. A., Hart, K. C., Karch, K. M., & . . . Ries, E. E. (2009). An intervention for relational and physical aggression in early childhood: A preliminary study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 1528. doi:10.1016/ j.ecresq.2008.09.002. Piers, E. V. (1984). Piers-Harris childrens self-concept scale. Los Angeles, CA: Psychological Services. Sartori, R. S. (2000). Lively lessons for classroom sessions. Warminster, PA: MAR-CO Products, Inc. Sartori, R. S. (2004). More lively lessons for classroom sessions. Warminster, PA: MAR-CO Products, Inc. Savidge, C., Christie, D., Brooks, E., Stein, S. M., & Wolpert, M. (2004). A pilot social skills group for socially disorganized children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 289296. doi:10.1177/1359104504041926. Shechtman, Z. (2002). Child group psychotherapy in the schools at the threshold of a new millennium. Journal of Counseling and Development, 80, 293299. Retrieved from www.counseling.org

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

94

Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 1(2)

Schectman, Z., Bar-el, O., & Hadar, E. (1997). Therapeutic factors and psychoeducational groups for adolescents: A comparison. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22, 203213. doi:10.1080/01933929708414381. Smith, J. D., Schneider, B. H., Smith, P. K., & Ananiadou, K. (2004). The effectiveness of whole-school antibullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review, 33, 574560. Retrieved from http:// www.nasponline.org Steyn, H. S., Jr., & Ellis, S. M. (2010). Estimating an effect size in one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44, 106129. doi:10.1080/ 00273170802620238. Walker, H. M., & McConnell, S. R. (1995). The WalkerMcConnell scale of social competence and school adjustment: Elementary version. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing. Whitney, I., & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Education Resources, 35, 325. Zimprich, D., Perren, S., & Hornung, R. (2005). A two-level confirmatory factor analysis of a modified Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 465481. doi:10.1177/0013164404272487.

on Measurement and Evaluation Systems at the University of Arkansas. Her research interests include clinical interventions and outcome evaluation in counseling and supervision, prevention and intervention programming for at-risk children, and measurement and evaluation in counseling. Bonni A. Behrend is a Masters candidate in Educational Statistics and Research Methods and a Masters student in the Counselor Education Program specializing in clinical mental health counseling at the University of Arkansas. Her research interests include self regulation and the effects of social and emotional issues of school-age children on goal achievement. Karyl L. Lounsbery, MS, LAC, is a doctoral student in the Counselor Education Program at the University of Arkansas. Her research interests include the effect of religious prejudice on the GLBT community and gender identity. Kristin K. Higgins, PhD, LPC, is as assistant professor in the Counselor Education Program at the University of Arkansas. Her research interests include school and school-based counseling interventions, accountability for school counseling interventions, children with autism spectrum disorders, and measurement and evaluation. Wen-Juo Lo, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Educational Statistics and Research Methods Program and on faculty at the National Office for Research on Measurement and Evaluation Systems at the University of Arkansas. His research interests include statistical methods for the detection of bias in educational and psychological measurement.

Bios

Rebecca A. Newgent, PhD, LPC, NCC, is an associate professor in the Counselor Education Program and on faculty at the National Office for Research

Downloaded from cor.sagepub.com by guest on March 16, 2012

Вам также может понравиться

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsОт EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsОценок пока нет

- A Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationОт EverandA Qualitative Case Study of Best Practices in Holistic EducationОценок пока нет

- Schonert Reichl2011Документ21 страницаSchonert Reichl2011ghada mohsenОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2: Literature Review and Data Collection ProtocolДокумент13 страницAssignment 2: Literature Review and Data Collection Protocolapi-460175800Оценок пока нет

- A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of Child-Focused Psychiatric Consultation and A School Systems-Focused Intervention To Reduce AggressionДокумент10 страницA Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of Child-Focused Psychiatric Consultation and A School Systems-Focused Intervention To Reduce AggressionFlorinaОценок пока нет

- CD FINAL Research Report For NREPP 2014Документ95 страницCD FINAL Research Report For NREPP 2014Nguyễn Ngọc Khánh PhươngОценок пока нет

- Asperger BeaumontДокумент12 страницAsperger BeaumontJose Gregorio Ortiz RОценок пока нет

- BeaumontДокумент13 страницBeaumontericaxiangozОценок пока нет

- Durlak Et Al. (2011) Meta Analysis SELДокумент28 страницDurlak Et Al. (2011) Meta Analysis SELMihaela Maxim100% (1)

- Vaughn 1990Документ25 страницVaughn 1990Tan Ian LuiОценок пока нет

- 122298375Документ12 страниц122298375api-509940099Оценок пока нет

- Promoting Emotional Intelligence in Preschool Education - A Review of ProgramsДокумент16 страницPromoting Emotional Intelligence in Preschool Education - A Review of ProgramsFlorence RibeiroОценок пока нет

- Impact Enhancing Students Social Emotional Learning Meta Analysis School Based Universal InterventionsДокумент30 страницImpact Enhancing Students Social Emotional Learning Meta Analysis School Based Universal Interventionsayça firatОценок пока нет

- Schonert-Reichletal ROESMHE2012Документ22 страницыSchonert-Reichletal ROESMHE2012Sochsne CampbellОценок пока нет

- A Meta-Analytic Study Investigating The Efficiency of Socio-Emotional Learning Programs On The Development of Children and AdolescentsДокумент7 страницA Meta-Analytic Study Investigating The Efficiency of Socio-Emotional Learning Programs On The Development of Children and AdolescentsMonica AlexandruОценок пока нет

- Luczynski Hanley 2013 Preventing Problem BehaviorДокумент15 страницLuczynski Hanley 2013 Preventing Problem BehaviorAlexandra AddaОценок пока нет

- Banda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFДокумент7 страницBanda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFMuhammad Bilal ArshadОценок пока нет

- Lessons For Teaching Social and Emotional CompetenceДокумент9 страницLessons For Teaching Social and Emotional CompetenceAdomnicăi AlinaОценок пока нет

- Ezmeci & Akman, 2023Документ7 страницEzmeci & Akman, 2023florinacretuОценок пока нет

- Mindfulness For Preschoolers - Effects On Prosocial Behavior, Self-Regulation and Perspective TakingДокумент21 страницаMindfulness For Preschoolers - Effects On Prosocial Behavior, Self-Regulation and Perspective TakingQuel PaivaОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Teaching Social Skills To Twice ExceptionalДокумент12 страницRunning Head: Teaching Social Skills To Twice Exceptionalapi-365141997Оценок пока нет

- CASEL SEL Findings K-8Документ12 страницCASEL SEL Findings K-8ina safitriОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Trauma-Based TrainingДокумент11 страницThe Impact of Trauma-Based TrainingMackenzie AganОценок пока нет

- Clinical Case Studies.Документ14 страницClinical Case Studies.Andreea NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Froi 2Документ17 страницFroi 2Froilan MartizanoОценок пока нет

- Ed 512777Документ18 страницEd 512777FAUZAN FAIQОценок пока нет

- Apsy Assign 2 FinalДокумент14 страницApsy Assign 2 Finalapi-164171522Оценок пока нет

- Social Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersДокумент11 страницSocial Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersbmwardОценок пока нет

- A Study On Social Maturity, School Adjustment and Academic Achievement Among Residential School GirlsДокумент13 страницA Study On Social Maturity, School Adjustment and Academic Achievement Among Residential School GirlsAlexander DeckerОценок пока нет

- Lewis Sugai Colvin 1998Документ21 страницаLewis Sugai Colvin 1998Neiler OverpowerОценок пока нет

- Journal of School PsychologyДокумент22 страницыJournal of School PsychologyClaudia OvalleОценок пока нет

- Mental Health ResearchДокумент6 страницMental Health ResearchArianna KelawalaОценок пока нет

- Powell, Boxmeyer, and Lochman - Social Problem-Solving Skills Training Sample Module From The Coping Power ProgramДокумент32 страницыPowell, Boxmeyer, and Lochman - Social Problem-Solving Skills Training Sample Module From The Coping Power ProgramM. MikeОценок пока нет

- Effect of Personal and Social Responsibility-Based Social-Emotional Learning Program On Emotional IntelligenceДокумент12 страницEffect of Personal and Social Responsibility-Based Social-Emotional Learning Program On Emotional IntelligenceAnonymousОценок пока нет

- Artigo Social Stories 2Документ19 страницArtigo Social Stories 2Maria Elisa Granchi FonsecaОценок пока нет

- #5 - McLeod, Sutherland, Martinez, Conroy, Snyder, Southam-Gerow (2017)Документ10 страниц#5 - McLeod, Sutherland, Martinez, Conroy, Snyder, Southam-Gerow (2017)Maria CordeiroОценок пока нет

- Luczynski 2014Документ18 страницLuczynski 2014Cursos Aprendo másОценок пока нет

- Empirically Valid Strategies To Improve Social and EmotionalДокумент28 страницEmpirically Valid Strategies To Improve Social and EmotionalMichelle Pajuelo100% (1)

- Schonert-Reichl Et Al. MindUpДокумент15 страницSchonert-Reichl Et Al. MindUpPeterОценок пока нет

- Tse2007 Article SocialSkillsTrainingForAdolescДокумент9 страницTse2007 Article SocialSkillsTrainingForAdolescGabriel BrantОценок пока нет

- Durlak Et Al 2011 - The Impact of Enhancing Students SELДокумент28 страницDurlak Et Al 2011 - The Impact of Enhancing Students SELTaeng TubeОценок пока нет

- Student LearningДокумент12 страницStudent LearningMae Ann PinedaОценок пока нет

- Implementation of The AIM Social Skills CurriculumДокумент22 страницыImplementation of The AIM Social Skills CurriculumBrunna FalgaterОценок пока нет

- 11041.english - SEPARATA EJREP Revisada InglesДокумент36 страниц11041.english - SEPARATA EJREP Revisada InglesNhung HồngОценок пока нет

- Stratton 17 2Документ18 страницStratton 17 2Patricia TanaseОценок пока нет

- 3 TitlesДокумент10 страниц3 Titlestomasjunio36Оценок пока нет

- Berry Et Al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)Документ59 страницBerry Et Al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)ceglarzsabiОценок пока нет

- The Utility of Vygotskian Behavioral Criteria in The Early Childhood Classroom: Learning From Non-ComplianceДокумент9 страницThe Utility of Vygotskian Behavioral Criteria in The Early Childhood Classroom: Learning From Non-ComplianceoliverОценок пока нет

- A Validation of The Social Skills Domain of The Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales With Chinese PreschoolersДокумент23 страницыA Validation of The Social Skills Domain of The Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales With Chinese Preschoolersyanfang liОценок пока нет

- Developmental Trajectories of Children's Social Competence in Early Childhood - The Role of The Externalizing Behaviors of Their Preschool PeersДокумент26 страницDevelopmental Trajectories of Children's Social Competence in Early Childhood - The Role of The Externalizing Behaviors of Their Preschool Peersmni.chenlinОценок пока нет

- Journal of School Psychology Volume 38Документ23 страницыJournal of School Psychology Volume 38Gentleman.zОценок пока нет

- Promoting Childrens and Adolescents Social and Emotional DevelopmentДокумент16 страницPromoting Childrens and Adolescents Social and Emotional DevelopmentViviana MuñozОценок пока нет

- The Challenging Behaviors Faced by The Preschool Teachers in Their ClassroomДокумент26 страницThe Challenging Behaviors Faced by The Preschool Teachers in Their ClassroomEDDIE LYN SEVILLANOОценок пока нет

- Teaching Social and Emotional Skills To Students in Vietnam Challenges and OpportunitiesДокумент9 страницTeaching Social and Emotional Skills To Students in Vietnam Challenges and OpportunitiesAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteОценок пока нет

- Action Research ProposalДокумент11 страницAction Research Proposalapi-305525161Оценок пока нет

- JPSP - 2023 - 64Документ14 страницJPSP - 2023 - 64badasahirpesaj0906Оценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Colouring For Test Anxiety in AdolescentsДокумент22 страницыEffectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Colouring For Test Anxiety in AdolescentsBachtiar Agung LaksonoОценок пока нет

- Development and Validation of The Social Emotional Competence Questionnaire (SECQ)Документ16 страницDevelopment and Validation of The Social Emotional Competence Questionnaire (SECQ)roxanacriОценок пока нет

- Sprague Horner PBS PaperДокумент19 страницSprague Horner PBS PaperMarília RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Stern 2016Документ19 страницStern 2016Monalisa CostaОценок пока нет

- Europass CV Lokesh NandreДокумент5 страницEuropass CV Lokesh NandreAbhishek Ajay DeshpandeОценок пока нет

- Islamization Abdulhameed Abo SulimanДокумент7 страницIslamization Abdulhameed Abo SulimanMohammed YahyaОценок пока нет

- NOIDAДокумент7 страницNOIDAMlivia DcruzeОценок пока нет

- Maths c4 June 2012 Mark SchemeДокумент14 страницMaths c4 June 2012 Mark SchemeAditya NagrechàОценок пока нет

- Kid Friendly Florida ELA Text Based Writing Rubrics: For 4 and 5 GradeДокумент5 страницKid Friendly Florida ELA Text Based Writing Rubrics: For 4 and 5 Gradeapi-280778878Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan (Grade 11TH) Unit 11 - WritingДокумент3 страницыLesson Plan (Grade 11TH) Unit 11 - WritingSir CrocodileОценок пока нет

- Health Equity: Ron Chapman, MD, MPH Director and State Health Officer California Department of Public HealthДокумент20 страницHealth Equity: Ron Chapman, MD, MPH Director and State Health Officer California Department of Public HealthjudemcОценок пока нет

- Essay Writing Digital NotebookДокумент10 страницEssay Writing Digital Notebookapi-534520744Оценок пока нет

- Dr. Manish Kumarcommunity Mental HealthДокумент63 страницыDr. Manish Kumarcommunity Mental HealthManish KumarОценок пока нет

- ID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramДокумент2 страницыID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramfauzanОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting The Utilization of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hiv Among Antenatal Clinic Attendees in Federal Medical Centre, YolaДокумент9 страницFactors Affecting The Utilization of Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hiv Among Antenatal Clinic Attendees in Federal Medical Centre, YolaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Cae - Gold PlusДокумент4 страницыCae - Gold Plusalina solcanОценок пока нет

- Engaging Senior High School Students Through Competitive CollaborationДокумент5 страницEngaging Senior High School Students Through Competitive Collaborationjanapearl.jintalanОценок пока нет

- Summary and Outlining Assessment 5 Types of ListeningДокумент2 страницыSummary and Outlining Assessment 5 Types of Listeningapi-267738478Оценок пока нет

- International Baccalaureate ProgrammeДокумент5 страницInternational Baccalaureate Programmeapi-280508830Оценок пока нет

- 1 Evaluation of Buildings in Real Conditions of Use - Current SituationДокумент11 страниц1 Evaluation of Buildings in Real Conditions of Use - Current Situationhaniskamis82Оценок пока нет

- PCR 271Документ205 страницPCR 271mztayyabОценок пока нет

- Syllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language English 0500Документ36 страницSyllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language English 0500Kanika ChawlaОценок пока нет

- Ifakara Position AnnouncementДокумент2 страницыIfakara Position AnnouncementRashid BumarwaОценок пока нет

- NIA 1 - National Investigation Agency - Deputaion Nomination - DT 07.09.21Документ10 страницNIA 1 - National Investigation Agency - Deputaion Nomination - DT 07.09.21Adarsh DixitОценок пока нет

- Daria EpisodesДокумент14 страницDaria EpisodesValen CookОценок пока нет

- 1231Документ7 страниц1231Mervinlloyd Allawan BayhonОценок пока нет

- Wh-Questions: Live Worksheets English English As A Second Language (ESL) Question WordsДокумент3 страницыWh-Questions: Live Worksheets English English As A Second Language (ESL) Question WordsDevaki KirupaharanОценок пока нет

- Lista Manuale Macmillan Aprobate Şi Recomandate: Nr. Crt. Manual Level Aprobat MECT Clasa L1 L2 L3Документ4 страницыLista Manuale Macmillan Aprobate Şi Recomandate: Nr. Crt. Manual Level Aprobat MECT Clasa L1 L2 L3Cerasela Iuliana PienoiuОценок пока нет

- Lessonn 1.2 ActivityДокумент2 страницыLessonn 1.2 ActivityDanica AguilarОценок пока нет

- 200 Sanskrit Terms GRДокумент12 страниц200 Sanskrit Terms GRUwe HeimОценок пока нет

- Conduct Surveysobservations ExperimentДокумент20 страницConduct Surveysobservations ExperimentkatecharisseaОценок пока нет

- 12 Statistics and Probability G11 Quarter 4 Module 12 Computating For The Test Statistic Involving Population ProportionДокумент27 страниц12 Statistics and Probability G11 Quarter 4 Module 12 Computating For The Test Statistic Involving Population ProportionLerwin Garinga100% (9)

- Games and Economic Behavior Volume 14 Issue 2 1996 (Doi 10.1006/game.1996.0053) Roger B. Myerson - John Nash's Contribution To Economics PDFДокумент9 страницGames and Economic Behavior Volume 14 Issue 2 1996 (Doi 10.1006/game.1996.0053) Roger B. Myerson - John Nash's Contribution To Economics PDFEugenio MartinezОценок пока нет

- InstituteCollegeStudyCenter 29102012014438PMДокумент7 страницInstituteCollegeStudyCenter 29102012014438PMAmir WagdarikarОценок пока нет