Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Mapping Global Values

Загружено:

Reflexive_ObjectionИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Mapping Global Values

Загружено:

Reflexive_ObjectionАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Mapping Global Values

Ronald Inglehart

Abstract

Modernization goes through two main phases, each of which brings distinctive changes in peoples worldviews. The Industrial Revolution was linked with a shift from traditional to secular-rational values, bringing bureaucratization, centralization, standardization and the secularization of authority. In the post-industrial phase of modernization, a shift from survival values to self-expression values, brings increasing emancipation from both religious and secular-rational authority. Rising mass emphasis on self-expression values makes democracy increasingly likely to emerge. Although the desire for freedom is a universal human aspiration, it does not take top priority when people grow up with the feeling that survival is uncertain. But when survival seems secure, increasing emphasis on self-expression values makes the emergence of democracy increasingly likely where it does not yet exist, and makes democracy increasingly eective where it already exists.

Introduction The world now contains nearly 200 independent countries, and the beliefs and values of their publics dier greatly, in thousands of dierent ways. Yet, among the many dimensions of cross-cultural variation, two are particularly important. Each dimension reects one of the two waves of economic development that have transformed the world economically, socially and politically in modern times: the transition from agrarian society to industrial society that emerged two hundred years ago and is now transforming China, India, Indonesia and many other countries; and the transition from industrial society to the post-industrial or knowledge society that began to emerge fty years ago and is now reshaping

Comparative Sociology, Volume 5, issue 2-3 2006 Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden also available online see www.brill.nl

116 Ronald Inglehart

the socioeconomic systems of the U.S., Canada, Western Europe, Japan, Australia and other economically advanced societies. These processes of economic and technological change have given rise to two key dimensions of cross-cultural variation: (1) a Traditional/SecularRational dimension that reects the contrast between the relatively religious and traditional values that generally prevail in agrarian societies, and the relatively secular, bureaucratic and rational values that generally prevail in urban, industrialized societies; and (2) a Survival/Self-expression dimension that also taps a wide range of beliefs and values, reecting an inter-generational shift from an emphasis on economic and physical security above all, towards increasing emphasis on self-expression, subjective well-being, and quality of life concerns. These dimensions are robust aspects of cross-cultural variation, and they make it possible to map the position of any society on a two-dimensional map that reects their relative positions at any given time. But gradual shifts are occurring along these dimensions, transforming many aspects of society. One of the most important of these changes is the fact that the shift toward increasing emphasis on Self-expression values makes democratic political institutions increasingly likely to emerge and ourish. Our analysis is based on a body of survey evidence that represents 85 percent of the worlds population. Data from four waves of the Values Surveys, carried out from 1981 to 2001, indicate that major cultural changes are occurring, and that a societys religious tradition, colonial history, and other major historical factors, give rise to distinctive cultural traditions that continue to inuence a societys value system despite the forces of modernization. Modernization and Cultural Change In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, modernization theorists from Karl Marx to Max Weber analyzed the emerging industrial society and tried to predict its future. Their analyses of cultural change emphasized the rise of rationality and the decline of religion, and they assumed that these developments would continue in linear fashion, with the future being a continuation of the same trends that were occurring during the 19th century. From todays perspective, it is clear that modernization is more complex than these early views anticipated. The numbers of industrial workers ceased growing decades ago in economically advanced societies, and virtually no one any longer expects a proletarian revolution. Moreover, it is increasingly evident that religion has not vanished as predicted. Furthermore, it is apparent that modernization can not be equated with Westernization, as early analyses assumed. Non-Western societies in East Asia have surpassed their Western role models in key aspects of

Mapping Global Values 117

modernization such as rates of economic growth and high life expectancy, and few observers today attribute moral superiority to the West. Although, today, few people accept the original Marxist version of modernization theory, one of its core concepts still seems valid: the insight that, once industrialization begins, it produces pervasive social and cultural consequences, from rising educational levels to changing gender roles. This article maps cross-cultural variation using data from the World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys, which have measured the beliefs and values of most of the worlds people. These surveys oer an unprecedentedly rich source of insight into the relationships between economic development and social and political change. They show that, even during the relatively brief time since the rst wave of the Values Surveys was carried out in 1981, substantial changes have occurred in the values and beliefs of the publics of these societies. These changes are closely linked with the economic changes experienced by a given society. As we will demonstrate, economic development is associated with predictable changes away from absolute norms and values, toward a syndrome of increasingly rational, tolerant, trusting, and post-industrial values. But we nd evidence of both massive cultural change and the persistence of traditional values. Throughout most of history, survival has been uncertain for most people. But the remarkable economic growth of the era following World War II, together with the rise of the welfare state, brought fundamentally new conditions in advanced industrial societies. The postwar birth cohorts of these countries grew up under conditions of prosperity that were unprecedented in human history, and the welfare state reinforced the feeling that survival was secure, producing an intergenerational value change that is gradually transforming the politics and cultural norms of advanced industrial societies. The best documented aspect of this change is the shift from Materialist to Postmaterialist priorities. A massive body of evidence gathered from 1970 to the present demonstrates that an intergenerational shift from Materialist to Postmaterialist priorities is transforming the behavior and goals of the people of advanced industrial societies (Inglehart, 1997; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). But recent research demonstrates that this trend is only one aspect of an even broader cultural shift from Survival values to Self-expression values. Economic development and cultural change move in two major phases, each of which gives rise to a major dimension of cross-national value dierences. Factor analysis of national-level data from the 43 societies studied in the 1990 World Values Survey found that two main dimensions accounted for well over half of the cross-national variance in more than a score of variables tapping basic values across a wide range of domains,

118 Ronald Inglehart

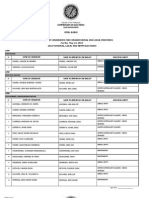

ranging from politics to economic life and sexual behavior (Inglehart, 1997). These dimensions of cross-cultural variation are robust; when the 1990-1991 factor analysis was replicated with the data from the 19951998 surveys, the same two dimensions of cross-cultural variation emerged even though the new analysis was based on 23 additional countries not included in the earlier study (Inglehart and Baker, 2000). The same two dimensions also emerged in analysis of data from the 2000-2001 surveys although numerous additional countries were again added to the pool, including eight predominantly Islamic societies a cultural region that had been relatively neglected in previous surveys (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). Each dimension taps a major axis of cross-cultural variation involving many dierent values. Table 1 shows the results of this most recent set of analyses, based on data from more than 70 societies, aggregated to the national level. Although each of the two main dimensions is linked closely with scores of values, for technical reasons, our indices were constructed by using only ve key indicators for each of the two dimensions.

Table 1 Two Dimensions of Cross-Cultural Variation First Factor (46%) TRADITIONAL VALUES emphasize the following: God is very important in respondents life It is more important for a child to learn obedience and religious faith than independence and determination [Autonomy index] Abortion is never justiable Respondent has strong sense of national prideRespondent favors more respect for authority (SECULAR-RATIONAL VALUES emphasize the opposite) Second Factor (25%) SURVIVAL VALUES emphasize the following: R. gives priority to economic and physical security over self expression and quality of life [4-item Materialist/Postmaterialist Values Index] Respondent describes self as not very happy Homosexuality is never justiable R. has not and would not sign a petition You have to be very careful about trusting people (SELF-EXPRESSION VALUES emphasize the opposite)

The original polarities vary; the above statements show how each item relates to the given factor. Source: World Values Survey data from more than 200 surveys carried out in four waves in 78 societies. (Factors = 2, varimax rotation, listwise deletion)

Factor Loadings .91 .88 .82 .81 .73

.87 .81 .77 .74 .46

Mapping Global Values 119

Human values are structured in a surprisingly coherent way: the two dimensions explain fully 71 percent of the cross-cultural variation among these ten items. More impressive still is the fact that each of these two dimensions taps a broad range of other attitudes, extending over a number of seemingly diverse domains. Table 2 shows the correlations of 24 additional variables that are relatively strongly linked with the rst dimension, showing correlations above the .40 level.

Table 2 Correlates of Traditional vs. Secular-rational Values TRADITIONAL values emphasize the following: Correlation with Traditional/ Secular Rational Values .89 .88 .81 .76 .75 .72 .71 .66 .65 .63 .61 .60 .57 .57 .57 .56 .56 .56 .53 .49 .45 .43 .41 .40

Religion is very important in respondents life Respondent believes in Heaven One of respondents main goals in life has been to make his/her parents proud Respondent believes in Hell Respondent attends church regularly Respondent has a great deal of condence in the countrys churches Respondent gets comfort and strength from religion Respondent describes self as a religious person Euthanasia is never justiable Work is very important in respondents life There should be stricter limits on selling foreign goods here Suicide is never justiable Parents duty is to do their best for their children even at the expense of their own well-being Respondent seldom or never discusses politics Respondent places self on Right side of a Left-Right scale Divorce is never justiable There are absolutely clear guidelines about good and evil Expressing ones own preferences clearly is more important than understanding others preferences My countrys environmental problems can be solved without any international agreements to handle them If a woman earns more money than her husband, its almost certain to cause problems One must always love and respect ones parents regardless of their behavior Family is very important in respondents life Relatively favorable to having the army rule the country R. favors having a relatively large number of children (SECULAR-RATIONAL values emphasize the opposite)

The number in the right hand column shows how strongly each variable is correlated with the Traditional/Secular-rational Values Index. The original polarities vary; the above statements show how each item relates to the Traditional/Secular-rational values index. Source: Nation-level data from 65 societies surveyed in the 1990 and 1996 World Values Surveys.

120 Ronald Inglehart

The Traditional/Secular-Rational dimension reects the contrast between the relatively religious and traditional values that generally prevail in agrarian societies, and the relatively secular, bureaucratic and rational values that generally prevail in urban, industrialized societies. Traditional societies emphasize the importance of religion, deference to authority, parent-child ties and two-parent traditional families, and absolute moral standards; they reject divorce, abortion, euthanasia, and suicide, and tend to be patriotic and nationalistic. In contrast, societies with secular-rational values display the opposite preferences on all of these topics. Table 3 shows 31 additional variables that are closely linked with the Survival/Self-expression dimension, which also taps a wide range of beliefs and values. A central component involves the polarization between Materialist and Postmaterialist values that reects an intergenerational shift from an emphasis on economic and physical security above all, towards increasing emphasis on self-expression, subjective well-being, and quality of life concerns. Societies that rank high on Survival values tend to emphasize materialist orientations and traditional gender roles; they are relatively intolerant of foreigners, gays and lesbians and other outgroups, show relatively low levels of subjective well-being, rank relatively low on interpersonal trust, and emphasize hard work, rather than imagination or tolerance, as important things to teach a child. Societies that emphasize Self-Expression values, display the opposite preferences on all these topics. These two dimensions are remarkably robust. If we compare the results from the two most recent waves of the Values Surveys, we nd a .92 correlation between the positions of given countries on the Traditional/ Secular-rational values dimension from one wave of the surveys to the next. With the Survival/Self-expression dimension, the positions of given countries are even more stable: their positions in the earlier wave show a .95 correlation with their positions ve years later. Although major changes are occurring along these dimensions, the relative positions of given countries are highly stable. If one compares the map based on the 1990 surveys with the map based on the 1995 surveys or the 2000 surveys, they initially seem to be the same map, showing given clusters of countries (such as Protestant Europe, the English-speaking countries, the Latin American societies, the Confucian societies) in the same relative position although each successive wave of surveys was not only carried out roughly ve years later than the previous one, but included many countries not covered in previous surveys. Figure 1 shows a two-dimensional cultural map on which the value systems of 80 societies are depicted, using the most recent data available for each country (mostly from the 2000 wave but in some cases

Mapping Global Values 121 Table 3 Correlates of Survival vs. Self-expression Values SURVIVAL values emphasize the following: Correlation with Survival/ Self-expression Values .86 .83 .83 .81 .78 .78 .75 .74 .74 .73 .73 .71 .69 .69 .68 .67 .67 .66 .66 .65 .64 .62 .62 .60 .60 .58 .56 .56 .55 .45 .42

Men make better political leaders than women Respondent is dissatised with nancial situation of his/her household A woman has to have children in order to be fullled R. rejects foreigners, homosexuals and people with AIDS as neighbors R. favors more emphasis on the development of technology R. has not recycled things to protect the environment R. has not attended a meeting or signed a petition to protect the environment When seeking a job, a good income and safe job are more important than a feeling of accomplishment and working with people you like R. is relatively favorable to state ownership of business and industry A child needs a home with both a father and mother to grow up happily R. does not describe own health as very good One must always love and respect ones parents regardless of their behavior When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women Prostitution is never justiable Government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for R. does not have much free choice or control over his/her life A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl R. does not favor less emphasis on money and material possessions R. rejects people with criminal records as neighbors R. rejects heavy drinkers as neighbors Hard work is one of the most important things to teach a child Imagination is not one of the most important things to teach a child Tolerance and respect for others are not the most important things to teach a child Scientic discoveries will help, rather than harm, humanity Leisure is not very important in life Friends are not very important in life Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections would be a good form of government R. has not and would not take part in a boycott Government ownership of business and industry should be increased Democracy is not necessarily the best form of government R. opposes sending economic aid to poorer countries (SELF-EXPRESSION values emphasize the opposite)

The number in the right hand column shows how strongly each variable is correlated with the Survival/Self-Expression Values Index. The original polarities vary; the above statements show how each item relates to the Traditional/Secular-rational values index. Source: nation-level data from 65 societies surveyed in the 1990 and 1996 World Values Surveys.

122 Ronald Inglehart

Figure 1 Cultural Map of the World in 2000

Secular-Rational values

2.0

1.5

Bulgaria China Estonia

Co

Russia S. Korea

Lith uania

ian fuc

East Germany Czech

Japan

Protestant Europe

Sweden

Norway Denmark Netherlands

1.0

Ukraine Belarus

0.5

Moldova

Montenegro Latvia Albania Serbia

Slovenia Taiwan Slovakia

West Germany Finland

Greece France

Switzerland

Hungary Macedonia Georgia Azerbaijan Armenia

nis mmu E x - C o Bosnia

Catholic Europe

Poland

Luxem bourg Iceland Belgium Israel Austria Great Italy Britain Croatia New Zealand Spain

-0.5

Romania

Uruguay Vietnam

English speaking

Canada Australia

N. Ireland U.S.A.

-1.0

-1.5

-2.0 -2

Turkey Portugal Ireland Indonesia Chile Argentina Bangladesh Philippines Dominican Iran Peru Republic Pakistan South Brazil Latin America Africa Jordan Mexico Uganda Nigeria Zimbabwe Algeria Egypt Venezuela Tanzania Morocco Colombia Puerto Afr ic a Rico El Salvador

South Asia

India

Traditional values

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0.5

1.5

Survival values

Self Expression values

from the 1995 wave). The vertical dimension represents the Traditional/ Secular-rational dimension, and the horizontal dimension reects the Survival/Self-expression values dimension. Both dimensions are strongly linked with economic development, with the value systems of rich countries diering systematically from those of poor countries. Thus, Germany, France, Britain, Italy, Japan, Sweden, the U.S. and all other societies with a 1995 annual per capita GNP over $15,000 rank relatively high on both dimensions: without exception, they fall in a broad zone near the upper right-hand corner. Conversely, every one of the societies with per capita GNPs below $2,000 falls into a cluster at the lower left of the map; India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Morocco, Brazil and Peru all fall into this economic zone, which cuts across the African, South Asian, ex-Communist, and Orthodox cultural zones. The remaining societies fall into interme-

Mapping Global Values 123

diate cultural-economic zones. Economic development seems to pull societies in a common direction regardless of their cultural heritage. Economic Development Interacts with a Societys Cultural Heritage Nevertheless, two centuries after the industrial revolution began, distinctive cultural zones persist. Dierent societies follow dierent trajectories, even when they are subjected to the same forces of economic development, because situation-specic factors, such as a societys cultural heritage, also shape how a particular society develops. Huntington (1996) has emphasized the role of religion in shaping the worlds eight major civilizations: Western Christianity, Orthodox, Islam, Confucian, Japanese, Hindu, African, and Latin American. Despite the forces of modernization, these zones were shaped by religious traditions that are still powerful today. Economic development is strongly associated with both dimensions of cultural change. But a societys cultural heritage also plays a role. Thus, all eleven Latin American societies fall into a coherent cluster, showing relatively similar values: they rank high on traditional religious values, but are characterized by stronger emphasis on Self-expression values than their economic levels would predict. Economic factors are important, but they are only part of the story; such factors as their common Iberian colonial heritage seem to have left an impact that persists centuries later. Similarly, despite their wide geographic dispersion, the English-speaking countries constitute a compact cultural zone. In the same way, the historically Roman Catholic societies of Western Europe (e.g., Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, Belgium and Austria) display relatively traditional values when compared with Confucian or ex-Communist societies with the same proportion of industrial workers. And, virtually all of the historically Protestant societies (e.g., West Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland) rank higher on both the traditional-secular rational dimension and the survival/self-expression dimension than do the historically Roman Catholic societies. All four of the Confucian-inuenced societies (China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan) have relatively secular values, constituting a Confucian cultural zone, despite substantial dierences in wealth. As Huntington claimed, the Orthodox societies constitute another distinct cultural zone. A societys religious and colonial heritage seem to have had an enduring impact on the contemporary value systems of the 80 societies. But a societys culture reects its entire historical heritage. A central historical event of the twentieth century was the rise and fall of a Communist empire that once ruled one-third of the worlds population. Communism

124 Ronald Inglehart

left a clear imprint on the value systems of those who lived under it. East Germany remains culturally close to West Germany despite four decades of Communist rule, but its value system has been drawn toward the Communist zone. And, although China is a member of the Confucian zone, it also falls within a broad Communist-inuenced zone. Similarly, Azerbaijan, though part of an Islamic cluster, also falls within the Communist superzone that dominated it for decades. Changes in GNP and occupational structure have important inuences on prevailing world views, but traditional cultural inuences persist. The ex-communist societies of Central and Eastern Europe all fall into the upper left-hand quadrant of our cultural map, ranking high on the Traditional/secular-rational dimension (toward the secular pole), but low on the Survival/self expression dimension (falling near the survivaloriented pole). A broken line encircles all of the societies that have experienced Communist rule, and, although they overlap with several dierent cultural traditions, they form a reasonably coherent group. Although by no means the poorest countries in the world, many Central and Eastern Europe societies have recently experienced the collapse of Communism, shattering their economic, political and social systems and bringing a pervasive sense of insecurity. Thus, Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova rank lowest of any countries on earth on the Survival/Selfexpression dimension, exhibiting lower levels of subjective well-being than much poorer countries such as India, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, Uganda and Pakistan. People who have experienced stable poverty throughout their lives tend to emphasize survival values, but those who have experienced the collapse of their social system (and may, as in Russia, currently have living standards and life expectancies far below where they were 15 years ago) experience a sense of unpredictability and insecurity that leads them to emphasize Survival values even more heavily than those who are accustomed to an even lower standard of living. Not surprisingly, Communist rule seems conducive to the emergence of a relatively secular-rational culture: the ex-Communist countries in general, and those that were members of the Soviet Union in particular (and thus experienced communist rule for seven decades, rather then merely four decades), rank higher on secular-rational values than noncommunist countries. And, to an equally striking extent, ex-communist countries in general, and former Soviet countries in particular, tend to emphasize survival values far more heavily than societies that have not experienced communist rule. Thus, as Inglehart and Baker (2000) demonstrate with multiple regression analysis, even when we control for level of economic development and other factors, a history of Communist rule continues to account for a signicant share of the cross-cultural variance in basic values (with

Mapping Global Values 125

seven decades of Communist rule having more impact than four decades). But, by comparison with societies historically shaped by a Roman Catholic or Protestant cultural tradition, an Orthodox tradition seems to reduce emphasis on Self-expression values. A societys position on the Survival/Self-expression values dimension has important political implications; as we will see, it is strongly linked with its level of democracy. Individualism, Autonomy and Self-expression Values As Tables 1, 2 and 3 demonstrated, the two main dimensions of crosscultural variation tap a wide range of beliefs and attitudes. But their ramications go farther still; the Survival/Self-expression values dimension taps a concept of major interest to psychologists, although they refer to it as individualism. The broad distinction between individualism and collectivism is a central theme in psychological research on cross-cultural dierences. Hofstede (1980) dened individualism as a focus on rights above duties, a concern for oneself and immediate family, an emphasis on personal autonomy and self-fulllment, and a basing of identity on ones personal accomplishments. Hofstede developed a survey instrument that measured individualism/collectivism among IBM employees in more than 40 societies. More recently, individualism has been measured cross-nationally by Triandis (1989, 2001, and 2003). Schwartz (1992, 1994, and 2003) measured the related concept of autonomy/embeddedness among students and teachers in scores of countries. As we will demonstrate, individualismcollectivism as measured by Hofstede and Triandis, and autonomy/ embeddness as measured by Schwartz, seem to tap the same dimension of cross-cultural variation as Survival/Self-expression values; they all reect the extent to which a given society emphasizes autonomous human choice. Individualism/collectivism, autonomy/embeddedness and survival/ self-expression values are all linked with the process of human development, which moves toward diminishing constraints on human choice (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). Self-expression values are dened in very similar terms to Hofstedes emphasis on personal autonomy and self-fulllment as core elements of individualism. Similarly, Schwartzs emphasis on intellectual autonomy and aective autonomy captures core elements of self-expression values. All of these variables reect a common theme: an emphasis on free choice. The core principle of collectivism is that groups bind and mutually obligate individuals. In collectivist societies, social units have a common fate and common goals; the personal is simply a component of the social,

126 Ronald Inglehart

making the in-group crucial. Collectivism implies that group membership is a central aspect of identity, and sacricing individual goals for the common good is strongly emphasized. Collectivism further implies that fulllment comes from carrying out externally dened obligations, making people focus on meeting others expectations. Accordingly, emotional self-restraint is valued to ensure harmony, even at the cost of ones own happiness. In collectivist societies, social context is prominent in peoples perceptions and causal reasoning, and meaning is contextualized. Finally, collectivism implies that important group memberships are seen as xed facts of life, toward which people have no choice; they must accommodate. Boundaries between in-groups and outgroups are stable, relatively impermeable, and important; exchanges are based on mutual obligations and patriarchal ties. Today, empirical measures of individualism, autonomy and self-expression values are available from many societies, and it turns out that they all tap a common dimension of cross-cultural variation, reecting an emphasis on autonomous human choice. The mean national scores on these three variables show are closely correlated, with an average strength of r = .66. As Table 4 demonstrates, factor analysis of the mean national scores from many countries reveals that individualism, autonomy and self-expression values all tap a single underlying dimension, which accounts for fully 78 percent of the cross- national variance. High levels of individualism go with high levels of autonomy and high levels of self-expression values. Hofstedes, Schwartzs, Triandis and Ingleharts measures all tap cross-cultural variation in a common aspect of human psychology: the drive toward broader human choice. As the Values Surveys demonstrate, they also measure something that extends far beyond whether given cultures have an individualistic or collective outlook. Societies that rank high on self-expression tend to emphasize individual autonomy and the quality of life, rather than economic and

Table 4 Self-expression Values and Individualism and Autonomy Scales tap a common dimension The Individualism/Autonomy/Self-expression Dimension: emphasis on autonomous choice (Principal Component Analysis) Inglehart, Survival vs. Self-expression values Hofstede, Individualism vs. Collectivism rankings Schwartz, Autonomy vs. Embeddedness, (mean of student/teacher samples) Variance explained 78% .91 .87 .87

Mapping Global Values 127

physical security. Their publics have relatively low levels of condence in technology and scientic discoveries as the solution to human problems, and they are relatively likely to act to protect the environment. These societies also rank relatively high on gender equality, tolerance of gays, lesbians, foreigners and other outgroups; they show relatively high levels of subjective well-being, and interpersonal trust, and they emphasize imagination and tolerance, as important things to teach a child. But individualism, autonomy and self-expression are not static characteristics of societies. They change with the course of socioeconomic development. As we have seen, socioeconomic development brings rising levels of existential security (especially in its post-industrial phase), which leads to an increasing emphasis on individualism, autonomy and self-expression. Birch and Cobb (1981) view this process as reecting an evolutionary trend towards the liberation of life. Inglehart and Welzel (2005) describe it as a process of human development in which the most distinctively human ability the ability to make autonomous choices, instead of following biologically and socially predetermined behavior becomes an increasingly central feature of modern societies. As we will see, this syndrome of individualism, autonomy, and self-expression is conducive to the emergence and survival of democratic institutions. The common dimension underlying individualism, autonomy and selfexpression is remarkably robust. It emerges even when one uses dierent measurement approaches, dierent types of samples, and dierent time periods. Hofstede found it in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when analyzing the values of a cross-national sample of IBM employees. Schwartz measured it in surveys of students and teachers carried out from 1988 to 2002; and Inglehart rst found it in an analysis of representative national samples of the publics of 43 societies surveyed in 1989-91, with the same dimension emerging in successive cross-national surveys in 1995 and in 2000. This dimension seems to be an enduring feature of crosscultural variation, to such an extent that one might almost conclude that it is dicult to avoid nding it if one measures the basic values of a broad range of societies. Individualism, Autonomy and Self-expression as Evolving Phenomena Most cultural-psychological theories have treated the individualismcollectivism polarity as a static attribute of given cultures, overlooking the possibility that individualist and collectivist orientations reect a societys socioeconomic conditions at a given time. Our theory holds that the extent to which Self-expression values (or individualism) prevail over

128 Ronald Inglehart

Survival values (or collectivism) reects a societys level of development; as external constraints on human choice recede, people (and societies) place increasing emphasis on self-expression values or individualism. This pattern is not culture-specic. It is universal. The most fundamental external constraint on human choice is the extent to which physical survival is secure or insecure. Throughout most of history, survival has been precarious for most people. Most children did not survive to adulthood, and malnutrition and associated diseases were the leading cause of death. This is remote from the experience of Western publics today, but existential insecurity is still the dominant reality in most of the world. Under such conditions, Survival values take top priority. Survival is such a fundamental goal that, if it seems uncertain, ones entire life strategy is shaped by that fact. Low levels of socioeconomic development not only impose material constraints on peoples choices; they also are linked with low levels of education and information. This intellectual poverty imposes cognitive constraints on peoples choices. Finally, in the absence of the welfare state, strong group obligations are the only form of social insurance, imposing social constraints on peoples choices. In recent history, a growing number of societies have attained unprecedented levels of economic development. Diminishing material, cognitive and social constraints on human choice are bringing a shift from emphasis on Survival values to emphasis on Self-expression values, and from a collective focus to an individual one. Peoples sense of human autonomy becomes stronger as objective existential constraints on human choice recede. As will be seen, this has important societal consequences. Mass emphasis on human choice tends to favor the political system that provides the widest room for choice: democracy. Economic Development and Cultural Change Because our two main dimensions of cross-cultural variation Traditional/ Secular-rational values and Survival/Self-expression values are linked with economic development, we nd pervasive dierences between the worldviews of people in rich and poor societies. Moreover, time series evidence shows that, with economic development, societies tend to move from the values prevailing in low-income societies toward greater emphasis on secular-rational and self-expression values (Inglehart and Baker, 2000; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). These changes largely reect a process of intergenerational value change. Throughout advanced industrial societies, the young emphasize

Mapping Global Values 129

self-expression values and secular-rational values more strongly than the old. Cohort analysis indicates that the distinctive values of younger cohorts are stable characteristics that persist as they age. Consequently, as younger birth cohorts replace older ones in the adult population, the societys prevailing values change in a roughly predictable direction. The unprecedented level of economic development during the past several decades, coupled with the emergence of the welfare state in advanced societies, means that an increasing share of the population has grown up taking survival for granted. Thus, priorities have shifted from an overwhelming emphasis on economic and physical security toward an increasing emphasis on subjective well-being, self-expression and quality of life. Inglehart and Welzel (2005) demonstrate that orientations have shifted from Traditional toward Secular-rational values, and from Survival values toward Self-expression values in almost all advanced industrial societies that have experienced economic growth. The Societal Impact of Changing Values Evidence from the Values Surveys demonstrates that peoples orientations concerning religion, politics, gender roles, work motivations, and sexual norms are evolving, along with their attitudes toward childrearing, their tolerance of foreigners, gays and lesbians, and their attitudes toward science and technology (Inglehart and Norris, 2003; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). Figure 2 provides one example, showing the percentage of respondents saying that homosexuality is Never justiable. The respondents were shown a ten-point scale, on which point 1 means that homosexuality is never justiable, and point 10 means that it is always justiable, with the eight intermediate points indicating intermediate positions. As this gure demonstrates, in 1981 about half of those surveyed in ve Western countries took the extreme negative position, placing themselves at point 1 on the scale (the publics of developing countries being even less tolerant of homosexuality). However, attitudes changed substantially in subsequent years. By the 2000 survey, only about 25 percent of the West Europeans, and 32 percent of the Americans took this position. Although attitudes toward homosexuality show a .86 stability correlation across the two most recent waves of the WVS, sizeable changes are occurring; most countries were changing, but their relative positions remained surprisingly stable, reecting an underlying component of continuity within given generations. Thus, change is occurring largely through intergenerational population replacement. The cumulative eect of changing attitudes in this eld has led to recent societal-level changes, such as the legalization of same-sex marriages

130 Ronald Inglehart

Figure 2 Changes in the percentage saying that homosexuality is never justiable, in Britain, France, Germany Italy, and the U.S., from 1981 to 2000

70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 W. Europe U.S. 1981 1990 1995 2000

in some countries and certain cities in the U.S. This, in turn, mobilized a strong reaction by people with traditional values and referenda seeking to ban same-sex marriage, giving rise to widespread belief that the U.S. public in general is becoming increasingly hostile to gays and lesbians; the opposite is true. The basic values of individuals are changing, and these changes have a major impact on a wide range of important societal-level phenomena. They are reshaping the extent to which given societies have objective gender equality in political, social and economic life, as well as human fertility rates, the role of religion, legislation concerning the rights of gays and lesbians, and environmental protection laws. Changing individuallevel values also seem to have a major inuence on the extent to which a society has good governance, and the emergence and ourishing of democratic institutions. Self-expression Values and Democracy A societys position on the survival/self-expression index is strongly correlated with its level of democracy, as indicated by its scores on the Freedom House ratings of political rights and civil liberties. This relationship is remarkably powerful, and it is clearly not a methodological artifact, since the two variables are measured at dierent levels and come from entirely dierent sources. Virtually all of the societies that rank high on Survival/Self-expression values are stable democracies. Virtually all of the societies that rank low on this dimension have authoritarian

Mapping Global Values 131

governments. We nd a correlation of .83 between survival/self-expression values and democracy; this is signicant at a very high level, and seems to reect a causal linkage (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005, articles 7 and 8). The Freedom House measures are limited by the fact that they only measure the extent to which civil and political liberties are institutionalized, which does not necessarily reect the extent to which these liberties are actually respected by political elites. Some very important recent literature has emphasized the importance of the distinction between formal democracy and genuine liberal democracy (Ottaway, 2003; ODonnell, Vargas Cullel and Iazzetta [eds.], 2004). In order to tap the latter, we need a measure of eective democracy which reects not only the extent to which formal civil and political liberties are institutionalized, but also measures the extent to which these liberties are actually practiced, thus indicating how much free choice people really have in their lives. To construct such an index of eective democracy, we multiply the Freedom House measures of civil and political rights by the World Banks anti-corruption scores (Kaufman, Kraay and Mastruzzi, 2003), which we see as an indicator of elite integrity, or the extent to which state power actually follows legal norms (see Inglehart and Welzel, 2005 for a more detailed discussion of this index). When we examine the linkage between this measure of genuine democracy and mass self-expression values, we nd an amazingly strong correlation of r = .90 across 73 nations. This reects a powerful cross-level linkage, connecting mass values that emphasize free choice, and the extent to which societal institutions actually provide free choice. Figure 3 depicts the relationship between this index of eective democracy and mass self-expression values. The extent to which self-expression values are present in a society explains over 80 percent of the crossnational variance in the extent to which liberal democracy is actually practiced. These ndings suggest that the importance of the linkage between individual-level values and democratic institutions has been underestimated. Mass preferences play a crucial role in the emergence of genuine democracy (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). The linkage between mass self-expression values and democratic institutions is remarkably strong and consistent, having only a few outliers: such countries as China, Iran and Vietnam show lower levels of democracy than their publics values would predict. These countries have authoritarian regimes that are under growing societal pressure to liberalize, and we expect that they will liberalize within the next 15 to 20 years. Authoritarian rulers of some Asian societies have argued that the distinctive Asian values of these societies make them unsuitable for democracy (Lee and Zakaria, 1994; Thompson, 2000). But, in fact, the position

132 Ronald Inglehart

Figure 3 Self-expression values and Eective Democracy. From Inglehart and Welzel, 2005

HIGH 105

100 95 90 Austria Iceland Norway U.S.A.

Denmark

Finland

New Zeald. Netherld.

Sweden Switzerld. Canada Australia

Level of Effective Democracy (2000-2002)

85 80 75 70 65 Slovenia 60 55 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 Jordan

Moldova Albania Bangladesh Georgia Algeria Tanzania Pakistan Taiwan

G.B. Ireland Germany (E.) Germany (W.) Portugal Chile Israel Uruguay Italy Spain Japan France Belgium

Estonia

Hungary

South Africa Czech R. Slovakia Poland Lithuania

South Korea Latvia Bulgaria India Romania

Croatia

Dominican R.

Peru Brazil

El Salvad.

Philippines Argentina Turkey

Yugoslavia Venezuela

Mexico

LOW

0 5

Zimbabwe 10

Azerbaij

Russia Nigeria Egypt Indonesia China Belarus Uganda Iran

<

r = .90***

Vietnam 20

15

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

Percent Emphasizing Self-expression Values (mid 1990s)

of most Asian countries on Figure 5 is about what their level of socioeconomic development would predict. Japan ranks with the established Western democracies, both on the self-expression values dimension, and on its level of democracy. The positions of Taiwan and South Korea on both dimensions is similar to those of other relatively new democracies such as Hungary or Poland. The publics of Confucian societies are more supportive of democracy than is generally believed. Which comes rst a democratic political culture or democratic institutions? The extent to which people emphasize self-expression values is closely linked with the ourishing of democratic institutions. But what causes what? I have argued that economic development interacts with a societys cultural heritage, so that high levels of development (linked with the rise of the knowledge society) bring growing emphasis on Self-expression values, which produce strong mass demands for liberalization and democratic institutions. The reverse interpretation would be that democratic

Mapping Global Values 133

institutions give rise to the self-expression values that are so closely linked with them. In other words, democracy makes people healthy, happy, non-sexist, tolerant and trusting, and instills Post-materialist values. This interpretation is appealing, and, if it were true, it would provide a powerful argument for democracy, implying that we have a quick x for most of the worlds problems: adopt democratic institutions and live happily ever after. Unfortunately, the experience of the Soviet Unions successor states does not support this interpretation. Since their dramatic move toward democracy in 1991, they have not become healthier, happier, more trusting, more tolerant or more Postmaterialist: most of them have moved in exactly the opposite direction. The fact that their people are living in economic and physical insecurity seems to have more impact than the fact that their leaders are chosen by reasonably free elections. Moreover, the World Values Survey demonstrate that growing emphasis on self-expression values emerged through a process of inter-generational change within the authoritarian communist regimes; democratic regimes do not necessarily produce self-expression values, and self-expression values can emerge even within authoritarian regimes if they produce rising levels of existential security. Democratic institutions do not automatically produce a culture that emphasizes self-expression values. Instead, it seems that economic development gradually leads to social and cultural changes that make democratic institutions more likely to survive and ourish. That would help explain why mass democracy did not emerge until a relatively recent point in history, and why, even now, it is most likely to be found in economically more developed countries in particular, those that emphasize self-expression values over survival values. During the past few decades, most industrialized societies have moved toward increasing emphasis on Self-expression values, in an intergenerational cultural shift linked with economic development. In the long run, the process of intergenerational population replacement tends to make these values more widespread. The ourishing of democratic institutions is also contingent on economic development and political stability, but, other things being equal, the inter-generational shift toward increasing emphasis on Self-expression values produces growing mass pressures in favor of democracy. Conclusion Modernization is not linear. It goes through various phases, each of which brings distinctive changes in peoples worldviews. The Industrial

134 Ronald Inglehart

Revolution was linked with a shift from traditional to secular-rational values, bringing the secularization of authority. In the post-industrial phase of modernization, another cultural change becomes dominant: a shift from survival values to self-expression values, which brings increasing emancipation from authority. Rising self-expression values makes democracy increasingly likely to emerge indeed, beyond a certain point it becomes increasingly dicult to avoid democratization. Cross-cultural variation is surprisingly coherent, and a wide range of attitudes (reecting peoples beliefs and values in such dierent life domains as the family, work, religion, environment, politics and sexual behavior) reect just two major underlying dimensions: one that taps the polarization between traditional values and secular-rational values, and a second dimension that taps the polarization between survival values and self-expression values. The worlds societies cluster into relatively homogenous cultural zones, reecting their historical heritage, and these cultural zones persist robustly over time. Although the desire for freedom is a universal human aspiration, it does not take top priority when people grow up with the feeling that survival is uncertain. But, when survival seems secure, increasing emphasis on self-expression values makes the emergence of democracy increasingly likely where it does not yet exist, and makes democracy increasingly eective where it already exists. Conversely, adopting democratic institutions does not automatically make self-expression values peoples top priority. These values emerge when socioeconomic development gives rise to a subjective sense of existential security. This can occur under either democratic or authoritarian institutions, and, when it does, it generates mass demands for democracy. We nd that when socioeconomic development reaches the post-industrial phase, it produces a rising emphasis on self-expression values. These values give high priority to the civil and political liberties that are central to democracy, so the cultural shift from emphasis on Survival values to Self-expression values is inherently conducive to democracy. The powerful correlation shown in Figure 3 reects a causal process in which economic development gives rise to increasing emphasis on selfexpression values, which in turn lead to the emergence and ourishing of democratic institutions. Demonstrating that the rise of self-expression values is conducive to democracy, rather than the other way around, requires a complex empirical analysis that I will not present here since it appears in Inglehart and Welzel (2005). Analysis of data from scores of societies reveals two major dimensions of cross-cultural variation: a Traditional/Secular-Rational values dimen-

Mapping Global Values 135

sion and a Survival/Self-expression values dimension. These dimensions are deep-rooted aspects of cross-cultural variation, and they make it possible to map the position of any society on a two-dimensional map that reects their relative positions. Despite their relative stability, gradual shifts are occurring along these dimensions, and they are transforming many aspects of society. One particularly important change stems from the fact that the shift from Survival values toward Self-expression values, makes democratic political institutions increasingly likely to emerge and ourish. References

Birch, Charles and John B. Cobb Jr. 1981 The Liberation of Life: From the Cell to the Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Huntington, Samuel P. 1996 The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster. Hofstede, Geert 1980 Cultures Consequences: Intentional Dierences in Work-related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Inglehart, Ronald 1997 Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Inglehart, Ronald and Wayne Baker 2000 Modernization, Cultural Change and the Persistence of Traditional Values. American Sociological Review (February):19-51. Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel 2005 Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Massimo Mastruzzi 2003 Governance Matters III: Governance Indicators for 1996-2002. World Bank Policy Research Department Working Paper No. 2195, Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Lee, Kuan Yew and Fareed Zakaria 1994 Culture is Destiny: A Conversation with Lee Kuan Yew. Foreign Aairs 73 (2): 109-26. Norris, Pippa and Ronald Inglehart 2004 Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ODonnell, Guillermo, Jorge Vargas Cullel and Osvaldo Miguel Iazzetta (eds.) 2004 The Quality of Democracy: Theory and Applications. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. Ottaway, Marina 2003 Democracy Challenged: The Rise of Semi-Authoritarianism. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

136 Ronald Inglehart Schwartz, Shlalom H. 1992 Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. In Mark P. Zanna (ed.): Advances in Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press. 1-65. 1994 Beyond Individualism/Collectivism: New Cultural Dimensions of Values. In U. Kim, H.C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S-C. Choi, & G. Yoon (eds.), Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Method and Applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 85-119. 2003 Mapping and Interpreting Cultural Dierences around the World. in Henk Vinken, Joseph Soeters, and Peter Ester (eds.), Comparing Cultures, Dimensions of Culture in a Comparative Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Thompson, John B. 2000 The Survival of Asian Values as Zivilisationskritik. Theory and Society 29: 651-86. Triandis, Harry C. 1989 The Self and Social Behavior in Diering Cultural Contexts. Psychological Review 96: 506-20. 1995 Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 2001 Individualism and Collectivism. In D. Matsumoto (ed.) Handbook of CrossCultural Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003 Dimensions of Culture Beyond Hofstede. In Henk Vinken, Joseph Soeters, and Peter Ester (eds.), Comparing Cultures, Dimensions of Culture in a Comparative Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Weber, Max 1904 The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. [original, 1904-1905; English 1958 translation, 1958]. New York: Charles Scribners Sons.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Cultural Shaping of Depression: Somatic Symptoms in China, Psychological Symptoms in North America? Ryder Yang Zhu Yao Yi Heine Bagby 2008Документ14 страницThe Cultural Shaping of Depression: Somatic Symptoms in China, Psychological Symptoms in North America? Ryder Yang Zhu Yao Yi Heine Bagby 2008Reflexive_ObjectionОценок пока нет

- Bodenhausen Gawronsk Associative and Propositional Processes in Evaluation.Документ40 страницBodenhausen Gawronsk Associative and Propositional Processes in Evaluation.Reflexive_ObjectionОценок пока нет

- Mutua-Savages Victims and SaviorsДокумент9 страницMutua-Savages Victims and SaviorsReflexive_ObjectionОценок пока нет

- "Is There Really "Law" in International Affairs?" John R. BoltonДокумент48 страниц"Is There Really "Law" in International Affairs?" John R. BoltonReflexive_Objection100% (1)

- A Dual-Process Model of Reactions To Perceived StigmaДокумент17 страницA Dual-Process Model of Reactions To Perceived StigmaReflexive_ObjectionОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Understanding Algeria's 2019 Revolutionary Movement: Thomas SerresДокумент10 страницUnderstanding Algeria's 2019 Revolutionary Movement: Thomas SerresCrown Center for Middle East StudiesОценок пока нет

- Constitution Right To PrivacyДокумент44 страницыConstitution Right To Privacyprit196100% (1)

- Political Science - BA June-19Документ50 страницPolitical Science - BA June-19galehОценок пока нет

- The State Anthony de JasayДокумент221 страницаThe State Anthony de JasayArturo CostaОценок пока нет

- Democratic ValuesДокумент4 страницыDemocratic Valuesapi-515370726Оценок пока нет

- The Hon'Ble Supreme Court of Indiana: BeforeДокумент24 страницыThe Hon'Ble Supreme Court of Indiana: BeforeShivani Singh0% (1)

- Nishikant Dubey's NoticeДокумент2 страницыNishikant Dubey's NoticeShatabdi ChowdhuryОценок пока нет

- Series: New Media vs. Old PoliticsДокумент39 страницSeries: New Media vs. Old PoliticsTalha ImtiazОценок пока нет

- Ss Sample Paper 1Документ5 страницSs Sample Paper 1Tanish SharmaОценок пока нет

- Structural FunctionalismДокумент19 страницStructural Functionalismtopinson4all100% (1)

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- "RACE: ARAB, SEX: TERRORIST" - THE GENDER POLITICS OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Eugene Sensenig/GenderLink Diversity CentreДокумент24 страницы"RACE: ARAB, SEX: TERRORIST" - THE GENDER POLITICS OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, Eugene Sensenig/GenderLink Diversity CentreEugene Richard SensenigОценок пока нет

- Judiciary SummaryДокумент35 страницJudiciary SummaryMeshandren NaidooОценок пока нет

- The Tyranny of The MeritocracyДокумент1 страницаThe Tyranny of The MeritocracyKostasBaliotisОценок пока нет

- The Deep Ecology of Pentti Linkola With Chad HaagДокумент54 страницыThe Deep Ecology of Pentti Linkola With Chad HaagPeter Rulon-MillerОценок пока нет

- Issue 32Документ48 страницIssue 32Ac. Vimaleshananda Avt.Оценок пока нет

- Pol TheoryДокумент14 страницPol TheorypurplnvyОценок пока нет

- Political Parties Act Chapter 258 R.E. 2019 PDFДокумент33 страницыPolitical Parties Act Chapter 258 R.E. 2019 PDFEsther MaugoОценок пока нет

- Nomination ScriptДокумент2 страницыNomination ScriptLorenzo CuestaОценок пока нет

- Reading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Документ43 страницыReading and Writing Skills: Quarter 4 - Module 1Anna Marie Andal RanilloОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine News0% (1)

- Political Systems: Edwin S. Martin, Ph.D. UST, Graduate SchoolДокумент29 страницPolitical Systems: Edwin S. Martin, Ph.D. UST, Graduate SchoolEDWIN MARTINОценок пока нет

- Ipsos Poll On Pakistanis Acceptability of 2024 Election Results-6Feb24Документ5 страницIpsos Poll On Pakistanis Acceptability of 2024 Election Results-6Feb24Iqbal AnjumОценок пока нет

- Presentation UDE 2018Документ27 страницPresentation UDE 2018Alemayehu Eyasu TedlaОценок пока нет

- Neher1994 - Asian Style DemocracyДокумент14 страницNeher1994 - Asian Style DemocracyNguyen Thanh PhuongОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Right To Free InternetДокумент18 страницRight To Free InternetSushant KumarОценок пока нет

- Kerala and Cuba TharamangalamДокумент40 страницKerala and Cuba TharamangalamRosemary Varkey M.Оценок пока нет

- Cohen, Future of A Disillusion, NLR18601Документ16 страницCohen, Future of A Disillusion, NLR18601JeremyCohanОценок пока нет

- Data 0000Документ27 страницData 0000api-3709402Оценок пока нет