Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Lajoie Superior Court Ruling 0212

Загружено:

Alfonso RobinsonИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lajoie Superior Court Ruling 0212

Загружено:

Alfonso RobinsonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

25846223@COLL43

Connecticut Trial Court Official Decisions

301 EAGLE ST., LLC v. ZBA OF BRIDGEPORT, No. CV 11-6015612 S (Feb. 16, 2012) 301 Eagle Street, LLC v. Zoning Board of Appeals of the City of Bridgeport. 2012 Ct. Sup. 772 CV 11-6015612 S Connecticut Superior Court February 16, 2012 [EDITOR'S NOTE: This case is unpublished as indicated by the issuing court.] RADCLIFFE, J. CT Page 772-A MEMORANDUM OF DECISION FACTS The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, is the owner of property known as 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street in the City of Bridgeport. The parcel, which is located at the intersection of Eagle Street and Central Avenue in the city's East End, has been owned by 301 Eagle Street, LLC since August of 2007 (Ex. 1). Prior to title vesting in 301 Eagle Street, LLC, the Plaintiff's predecessor in title, Michael Infante, applied for a Certificate of Zoning Compliance (ROR 24, p. 5). The June 21, 2007 application, signed by Michael Infante, listed the proposed use as "two family dwelling with office, storage of building equipment, materials, dump truck and excavating equipment including loaders and shovels." When the property was purchased by 301 Eagle Street, LLC in August of 2007, it was situated in an Industrial Light (I-LI) zone. Effective January 1, 2010, the zoning classification was changed to Mixed Use-Light Industrial (MU-LI). On August 20, 2010, Bridgeport Zoning Enforcement Officer Neil Bonney issued a cease and desist order (ROR 4) to the Plaintiff, regarding the property at 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street. The cease and desist order followed a citizen complaint, and an extensive inspection of the site.

The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, appealed the cease and desist order to the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, which, following a hearing, upheld the action of the zoning enforcement officer, on December 14, 2010 (Supplemental ROR 3, p. 13-14.) This appeal followed. CT Page 772-B The cease and desist order (ROR 4) contained the following language: "You are hereby ordered to cease and desist the use and maintenance of the recycle-processing and transfer station at the above address in an MU-LI zone." The Plaintiff's appeal, dated September 2, 2010 (ROR 1), described the proposed development of the property as "Auto and truck salvage metal and building material salvage." The use of the property was stated as "Auto and travel (sic) salvage metal and building material salvage." In its appeal (ROR 1), the Plaintiff claimed the existence of a "hardship" based upon an alleged: "Pre-existing use. See Certificate of Zoning Compliance dated May 6, 2008 . . ." The Application for Certificate of Zoning Compliance tendered by the Plaintiff's attorney on May 6, 2008, less than one year after the June 21, 2007 application by the Plaintiff's predecessor in title, described the proposed use of the property as "Auto and truck salvage metal and building material salvage . . ." Although the application received over the counter approved on the day it was submitted, the certificate added a caveat: "automotive junk yard activity prohibited." The zoning enforcement field card dated May 6, 2008, initialed by zoning enforcement officer Dennis Buckley, contains the phrase "no work incidental to truck/equip. storage and scrap metals." A hand written notation states "storage only." No Special Permit or Coastal Area Management (CAM) Site Plan was submitted before or after May 6, 2008, concerning the use of the property for "Auto and truck salvage metal and building material salvage . . ." Furthermore, the May 6, 2008 application for a certificate of zoning compliance was submitted on behalf of "Lajoie's Auto Wrecking Company, Inc.," a sister corporation of the Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC. At trial, it was admitted that considerations of any alleged "hardship" are not pertinent to the Plaintiff's appeal of the August 20, 2010 cease and desist order. A hearing was held by the Defendant Zoning Board of Appeals concerning the cease and desist order on October 12, 2010 (ROR 24). Zoning Enforcement Officer Bonney reviewed the history of the property, including its use in 1953 as a freight terminal used for housing and servicing trucks. CT Page 772-C He reviewed the June 2007 Certificate of Zoning Compliance, and concluded that the

property was approved for "a contractor's storage yard," which permitted the storage of equipment, along with salvage materials, such as metal and wood (ROR 24, p. 5). Following the receipt of a complaint on August 17, 2010, two inspections of the premises were conductedthe first on August 17, 2010, and the second on August 24, 2010. The inspections revealed the following (ROR 24, p. 5-9): 1. A pole sign announcing Lajoie's Scrap Metal and Recycling, Bridgeport, Connecticut, with a phone number. 2. Dumpsters with writing "Lajoie's Scrap Metal Recycling," Norwalk. 3. Scrap metal on the ground in buckets and in dumpsters. 4. Scrap metal being delivered to the property and weighed. 5. Scrap metal being picked up with a claw machine. 6. A pneumatic cutting machine, located inside a building. 7. Operations on the site by a separate company to whom space is leased and who had no certificate of zoning compliance. 8. Use of the claw machine for compacting. 9. Noise caused by the use of equipment which made it difficult to hear. Bonney quoted a thirty (30) year employee of Lajoie's, who conducted the tour of the property as saying: "Scrap metal is brought into this facility, some by regular suppliers. It is weighed, and metals are separated by type and put into containers. Some metal is cut to divide different types of metal or to make suremake the size more manageable. Metals were put into containers, metals are packaged, bundled, separated." (ROR 24, p. 7.) Photographs depicting the coming and going of trucks from the site, and activities on the property (ROR 24, p. 8-9) were presented. The photos show extensive piles of tin and other metals. The zoning enforcement officer presented an advertisement, which read: "Lajoie's is coming to Bridgeport. Bring us your scrap. We pay dollars." The activities were advertised, on the site, as "scrap metal and recycling" (ROR 24, p. 9).

Bonney concluded by informing the Board that "the activities on the site did not conform to the regulations, either the 1996 regulations applicable CT Page 772-D to an ILI zone, or the applicable regulations in an MU-LI zone as of January 1, 2010." (ROR 24, p. 11-12.) Residents of the East End testified in favor of upholding the cease and desist order. Former state senate Ernest Newton stated that the site was approved for storage: "They were going to be a storage facility and that's what their permit calls for, that's what they should be," he said, before adding ". . . it's a poor area and they think they can do whatever they want . . ." (ROR 24, p. 14.) City Council member Andre Baker and Lillian Wade, the president of the East End Neighborhood Revitalization Zone (NRZ) testified concerning the effect of the facility on the immediate neighborhood. Ted Meekins, chairman of the East End Community Council, expressed similar sentiments. A resident of Eagle Street, Nelson Ruggles, claimed that activities on the site had changed. He stated that work now begins at 6:30 a.m., when machines are turned on, and excessive noise emanating from the site disturbs neighbors at all hours (ROR 24, p. 2122). Confronted by the extensive paper trail constructed by Neil Bonney, the site inspections, and the mountain of scrap metal depicted in the photographs, the attorney for 301 Eagle Street, LLC, informed the Zoning Board of Appeals that his client was not engaged in a recycling operation. When confronted by the sign advertising "recycling," the attorney opined: "well, the sign could say `beauty salon' . . . it doesn't really make a difference what it says." (ROR 24, p. 24.) Counsel argued, in a prepared Memorandum (ROR 16), that "several" certificates of zoning compliance had been received "as a contractor's yard and as a facility for scrap and salvage materials." He also claimed that the property "has been used legally as a scrap metal and salvage yard for many years," and that the use "predates the adoption of the zoning regulations and the zoning map on January 1, 2010." He therefore claimed that the "existing use" as a scrap and salvage yard was legally nonconforming. While no Special Permit or Coastal Area Management (CAM) Site Plan application was ever submitted to the Bridgeport Planning and Zoning Commission, the Plaintiff's attorney detailed his informal interaction with zoning official Dennis Buckley (ROR 24, p. 31-33), concerning the CT Page 772-E buying and selling of scrap metal on the site. He claimed that the current activities are "grandfathered" under the 1996 regulations and concluded his argument by claiming that his client had relied on documents issued by the City of Bridgeport. At trial, any estoppel theory was expressly disavowed by trial counsel.

Following the close of the October 12 public hearing, the Zoning Board of Appeals discussed the matter on the record. The item was tabled, pending receipt of additional information. Further discussion occurred on November 9, 2010. At that meeting Zoning Enforcement Officer Buckley said: "I didn't expect it would turn into what it is." (Supplemental ROR 2, p. 2.) The matter was again tabled by the Board. At its December 14, 2010 meeting, the Zoning Board of Appeals voted to deny the appeal of 301 Eagle Street, LLC, and to uphold the cease and desist order issued by the zoning enforcement official. The board voted to uphold the August 20, 2010 Cease and Desist order, based upon fourteen (14) specific findings: 1. Each member of the Board who will vote on this matter is personally acquainted with the Zoning Department file for 301 Eagle Street and is familiar with the site and its immediate environs and the information concerning the prior and current use of the subject property. 2. The record shows that the Certificates of Zoning Compliance issued between April 8, 1986 and November 10, 2009 under the Light Industrial Zoning Regulations allowed for storage only. The storage of metal is therefore a legally nonconforming use. 3. The Board specifically finds that the property is not being used solely for the storage of metals as allowed by the Certificate of Zoning Compliance dated May 6, 2008. The photographs clearly establish that the cutting and separation of metals is currently occurring on site. This cutting and separation of metal using a claw excavator is not permitted by the Certificate of Zoning Compliance issued May 6, 2008 to Lajoie's and is therefore not a legally nonconforming use. Appellants stated that scrap metal are brought in stored and removed. The record, however, demonstrates that this is not accurate. These metals are cut and separated using heavy and noisy equipment which is not a legally CT Page 772-F nonconforming use under any of the Certificates of Zoning Compliance.

4. The Certificates of Zoning Compliance issued to the former owner were limited to storage. The April 8, 1986 Certificate of Zoning Compliance issued to the former owner was limited to "storage." The June 21, 2007 Certificate of Zoning Compliance was limited to "storage yard," "storage of equipment," and "storage of building equipment. 5. The Certificates of Zoning Compliance issued to the current owner were limited to storage. The March 19, 2008 was limited to "buying and selling scrap metals." The May 6, 2009 Certificate of Zoning Compliance Field Card stated property was for "storage only." "No work incidental to truck/equip. storage and scrap metals." On March 10, 2010 the Certificate of Zoning compliance issued to Lajoie's was for "truck and equipment storage and scrap metal (storage only)." 6. The record clearly establishes that heavy equipment is being used in the open yard to cut and separate metal into separate containers of metal for recycling as documented by numerous photographs taken and received as of August 13, 2010 which were introduced into the record. The Zoning Enforcement Inspection Report dated August 17, 2010 states that the property was being used as a recycling facility with the metal being cut, separated packaged or bundled and then sent to Lajoie's facility to Norwalk to be recycled. These photographs show adjoining residences around the subject property. 7. The Board finds that the property is not being used solely for the storage of metal as allowed by the Certificate of Zoning Compliance dated May 6, 2008. The photographs clearly establish the current cutting and separating of metal is occurring on site. This cutting and separating of metal using a claw excavator is not a legally nonconforming use. Appellants stated that "scrap metal is brought in stored and removed." The record demonstrates that this is not accurate. These metals are cut and separated using heavy equipment which is not a legally nonconforming use. It is a prohibited use in the MU-LI zone. 8. Appellant neither proved hardship nor did it establish when it applied for an application for a Certificate of Zoning Compliance on May 6, 2008 to use the property for "buying and selling scrap metals" this also authorized the use of the property for "auto and travel salvage CT Page 772-G metal and building material salvage" as claimed on September 2, 2010. Since the property was not previously approved for "auto and travel salvage metal and building material salvage" this is not an approved pre-existing use. The

Board therefore finds that: 1) the existing legally conforming use of the property does include storage of metals; and 2) separating, crushing and cutting of metals is not a legally nonconforming use on this property. 9. The Board further finds that the appellant has subleased a portion of the site to a separate company which compacts metals and distributes scrap metal into dumpsters. No Certificate of Zoning Compliance has ever been filed for this tenant/subcontractor of Lajoie's Scrap Metal and Recycling, that this is not a legally nonconforming use, and is in fact a prohibited use. 10. The appellant claimed but never provided any specific claim for a hardship. The Board finds that the appellant did not establish any specific hardship. 11. The Board finds that the cutting and crushing of metals represents an illegal increase in the intensity of use of the property. 12. The Board finds that cutting and crushing of metals are prohibited uses and are detrimental to the general health safety and welfare. 13. The Board also finds that the cutting and crushing of metals is injurious, obnoxious, dangerous and a nuisance to the city and to the neighborhood through noise, vibration and dust. See Sec. 4-8-4. 14. Based on this factual record, the Board finds, Pursuant to Section 8-6 of the General Statutes and Section 7-7-4 of the Bridgeport Zoning Regulations, that the appeal of the Zoning Enforcement Official's order to comply must be denied. From this decision, upholding the cease and desist order, the Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, instituted this appeal. On April 25, 2011, the East End Tabernacle Church, Inc., Ivette Rodriguez, Nelson Burgos and the St. Mark's Day Care Center filed a Motion to Intervene as Defendants in this action. The Motion to Intervene was granted by the Court (Dooley, J.) on June 7, 2011 [52 Conn. L. Rptr. 187]. CT Page 772-H A Cross Appeal was filed by the Intervening Defendants on July 22, 2011. In their Cross Appeal, the Interveners challenge paragraph 5 of the conclusions reached by the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals.

They maintain, in the Cross Appeal: "To the extent that the Defendant ZBA found that there was a March 19, 2008 certificate of zoning compliance issued to the current owner authorizing the buying and selling of scrap metal at the property, such finding is erroneous." AGGRIEVEMENT The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, is the owner of property known as 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street, which is the subject of this appeal. The property was purchased by its current owner in August of 2007 (Ex. 1), and has been owned since that date. The four Intervening Defendants, East End Baptist Tabernacle Church, Ivette Rodriguez, Nelson Burgos and St. Mark's Day Care Center, Inc., entered into a stipulation of facts with the Defendant Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals (Ex. A). The Plaintiff, and the Intervening Defendants who are Plaintiffs on the Cross Claim, all claim to be aggrieved by the decision of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals which generated this appeal. Pleading and proof of aggrievement are prerequisites to a trial court's jurisdiction over the subject matter of an appeal. Jolly, Inc. v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 237 Conn. 184, 192 (1996); Winchester Woods Associates v. Planning & Zoning Commission, 219 Conn. 303, 307 (1991). The question of aggrievement is one of fact, which must be determined by the trial court. Primerica v. Planning & Zoning Commission, 211 Conn. 85, 93 (1989). Aggrievement falls into two broad categoriesstatutory aggrievement, and classical aggrievement. Statutory aggrievement exists by legislative fiat, which grants standing to appeal by virtue of a particular statute, rather than through an analysis of the facts of a particular case. Weill v. Lieberman, 185 Conn. 123, CT Page 772-I 124-25 (1986); Pierce v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 7 Conn.App. 632, 635-36 (1986). Section 8-8(a)(1) of General Statutes defines "aggrieved person" for purposes of an appeal from the decision of a municipal land use agency. The statute reads: (1) "Aggrieved person" means a person aggrieved by a decision of a board, and includes any officer, department, board or bureau of a municipality charged with enforcement of any order, requirement or decision of the board. In the case of a decision by a zoning commission or a zoning board of appeals, "aggrieved person" includes any person owning land that abuts or is within a radius of one hundred feet from any portion of the land involved in the decision of the board. Classical aggrievement requires a party to satisfy, through evidence at trial, as wellestablished two-fold test: 1) the party claiming aggrievement must demonstrate a specific

personal and legal interest in the decision appealed from, as distinguished from a general interest such as concern of all members of the community as a whole, and 2) the party must show that the specific personal and legal interest has been specifically and injuriously affected by the action of the agency. Cannavo Enterprises, Inc. v. Burns, 194 Conn. 43, 47 (1984); Hall v. Planning Commission, 181 Conn. 442, 444 (1980). The burden of proving aggrievement rests with the person or entity claiming to be aggrieved. London v. Planning & Zoning Commission, 149 Conn. 282, 284 (1962). Ownership of the property which is the subject of the appeal demonstrates a personal and legal interest in the subject matter of the decision appealed from. Huck v. Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Agency, 203 Conn. 525, CT Page 772-J 530 (1987); Bossert Corporation v. Norwalk, 157 Conn. 279, 285 (1968). The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, is the owner of 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street (Ex. 1). Its interest has been specifically and injuriously impacted by the action of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals which generated this appeal. It is therefore found that 301 Eagle Street, LLC is aggrieved by the decision which generated this appeal. The Intervening Defendants, Plaintiffs on the Cross Claim, maintain that they are aggrieved, based upon the Stipulation of Facts (Ex. A) received at the hearing on January 27, 2010. The East End Baptist Tabernacle Church, in addition to the church sanctuary located at 524 Central Avenue, 350 feet from the subject property, (Ex. A, par. 5), owns property at 290 Smith Street which abuts the property affected by the cease and desist Order. (Ex. A, par. 2.) It is therefore found that the East End Baptist Tabernacle Church is statutorily aggrieved. The Intervening Defendant Ivette Rodriguez owns property at 288 Eagle Street, where she resides with her husband, Nelson Burgos. The property is across the street from the property owned by the Plaintiff (Ex. A, par. 3). It is found that Ivette Rodriguez is statutorily aggrieved. The Stipulation of Facts states that the activities at 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street generate noise, dust vibrations and truck traffic. (Ex. A, par. 4.) The trucks arrive in the vicinity of the day care center, located at the corner of Newfield Avenue and Eagle Street, and deliver scrap metals and other materials to the site during the early morning hours. (Ex. A, par. 4-7.) Since the Plaintiff, and two of the Intervening Defendants have been determined to be statutorily aggrieved, the court has jurisdiction over both the appeal and the cross appeal, and it is unnecessary to determine whether the remaining Intervening Defendants are classically aggrieved.

However, since aggrievement is established if there is a possibility, as distinguished from a certainty, that some legally protected interest has been affected; Ponazi v. Conservation Commission, 220 Conn. 476, CT Page 772-K 483 (1991); it is found, based upon the stipulation of facts, that both Nelson Burgos and the St. Mark's Day Care Center are classically aggrieved by the decision of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals. STANDARD OF REVIEW When hearing an appeal from an order issued by a municipal zoning enforcement officer, a zoning board of appeals sits in a quasi-judicial capacity. In that capacity, the zoning board of appeals hears and decides an appeal de novo. Conetta v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 42 Conn.App. 133, 137 (1996). The board is charged with the responsibility of finding the facts, and applying the zoning regulations to those facts. Toffolon v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 155 Conn. 558, 560-61 (1967); Connecticut Sand & Stone Corporation v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 150 Conn. 439, 442 (1963). The action of the zoning enforcement official is entitled to no special deference by a reviewing court. Casserta v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 226 Conn. 80, 88-89 (1993). The Board is endowed with liberal discretion, and its actions are subject to review by a court only to determine whether the action was unreasonable, arbitrary or illegal. Pleasant Valley Farms Development, Inc. v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 218 Conn. 265, 269 (1991); Wing v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 61 Conn.App. 639, 643 (2001). The burden of proof to demonstrate that the board acted improperly is upon the party seeking to overturn the board's decision. Graff v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 277 Conn. 645, 669 (2006); Sciortino v. Zoning Board of Appeals, CT Page 772-L 87 Conn.App. 143, 147 (2005). A court may not substitute its judgment for that of the zoning board of appeals, so long as the board's decision reflects an honest judgment, reasonably arrived at, based upon the facts in the record. Jaser v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 43 Conn.App. 545, 548 (1996). The court's function is to determine on the basis of the record, whether substantial evidence has been presented to the board to support its findings. Huck v. Inland Wetlands &Watercourses Agency, supra, 540; Smith Bros. Woodland Management, LLC v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 108 Conn.App. 621, 628 (2008). The credibility of witnesses and the determination of factual issues are matters within the province of the agency. Stankiewicz v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 15 Conn.App. 729, 731-32 (1988). Section 8-7 of the General Statutes requires a zoning board of appeals to state upon the record the basis for its decision. Where, as here, the board has compiled a detailed and comprehensive statement in support of its decision, a court must determine whether any of the reasons given is supported by substantial evidence. Gibbons v. Historic District Commission, 285 Conn. 755, 770-71 (2008); Vine v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 281 Conn. 553, 559-60 (1988).

USE OF THE PROPERTY AS A SCRAP METAL AND SALVAGE YARD WAS NOT A PERMITTED USE UNDER THE INDUSTRIAL LIGHT (I-LI) ZONING REGULATIONS The Plaintiff claims that 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street has been legally used as a scrap metal and salvage yard for many years. It further contends that such legal use predated the adoption of zoning regulations which changed the CT Page 772-M property from Industrial Light (I-LI) to Mixed Use Light Industrial (MU-IL) on January 1, 2010. This claim finds no support in the record, and is unable to withstand even minimal scrutiny. In order for use to be considered nonconforming under a municipal zoning regulation, it 1) must be a lawful use, and 2) must have been in existence at the time the zoning regulations making the use nonconforming were enacted. Helicopter Associates, Inc. v. Stamford, 201 Conn. 700, 712 (1986); Petruzzi v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 176 Conn. 479, 482-83 (1979). Nonconforming uses are protected by statute. Section 8-2 of the General Statutes provides that regulations enacted by a municipal planning and zoning commission "shall not prohibit the continuance of any nonconforming use, building or structure existing at the time of the adoption of such regulations." A lawfully established nonconforming use is a vested right, which runs with the land, and is entitled to constitutional protection. Petruzzi v. Zoning Board of Appeals, supra, 484. It may continue as it existed before the date of the adoption of the zoning regulation rendering it nonconforming. Essex Landing, Inc. v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 206 Conn. 595, 607 (1988); Helbig v. Zoning Commission, 185 Conn. 294, 306 (1981). The use of the property as a legal nonconforming use is permitted, because it legally existed when the adoption of new regulations rendered it nonconforming. Adolphson v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 206 Conn. 595, 607 (1988). The burden is on the owner of the property to prove the existence of a nonconforming use. Pleasant Valley Farms Development, Inc. v. Zoning Board of Appeals, supra, CT Page 772-N 272; Friedson v. Westport, 181 Conn. 230, 234 (1980). When 301 Eagle Street, LLC purchased the subject property in 2007, it was located in an IL-L zone. Section 7-3-1 of the Bridgeport Zoning Regulations defines the purpose of the zone: "The Light Industrial (I-LI) zone is intended to promote a concentration of industrial uses having minimal off-site impacts . . ." This purpose is certainly consistent with the Certificate of Zoning Compliance issued less than two months prior to the purchase, on June 21, 2007. That document described a proposed use for ". . . storage of building equipment, materials, dump trucks, and excavating equipment . . ." In other words, the Certificate of Zoning Compliance described a legally nonconforming contractor's storage yard.

The I-LI regulations provide for certain Industrial Uses, including "Auto and truck salvage and wrecking." (Second Supplemental ROR 1, p. 83.) However, pursuant to Table 7-3-2, Industrial Services uses are only permitted, after a Special Permit has been issued following favorable action by the Bridgeport Planning and Zoning Commission. (Second Supplemental ROR, p. 69-70; Special Permit Procedures, p. 143-44.) A General Statute, S. 8-3c(b) requires that a public hearing be conducted by the body being asked to issue the Special Permit. This is part of a process which involves scrutiny by members of the planning and zoning commission, and the public, in an open forum. A planning and zoning commission may impose conditions, prior to granting any request for a Special Permit. The process mandates transparency, and provides for both public and zoning commission input and scrutiny which is not present when a certificate of zoning compliance is sanctioned over the counter. The record clearly demonstrates that neither the current owner, or its predecessor in title, sought to establish a permitted use in the I-LI zone, through resport to the Special Permit process. Nor does it appear that the sale of the property was in any way conditioned upon the ability of the buyer to secure a Special Permit for either an "Auto and truck salvage and wrecking" use, or a "metal and building CT Page 772-O materials, salvage or wrecking . . ." use, from land use agencies of the City of Bridgeport. Whether this failure, as suggested at the October 12 hearing, represented a calculated decision because the East End "is a poor area, and they think . . . they can do whatever they want," or resulted from mere inadvertence, cannot be conclusively determined from the record. However, it is unambiguously clear that the use of 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street for either purpose was not a permitted use in the I-LI zone when the zoning classification was changed on January 1, 2010. Therefore, the Plaintiff cannot claim that a legal use was rendered nonconforming by virtue of the change in zoning classification. Nor can the Plaintiff utilize the May 6, 2008 Certificate of Zoning Compliance to accomplish through private meetings, that which he did not seek to accomplish through the Special Permit process. The field card dated May 6, 2008 contains the handwritten notes "storage only," and "automotive junk yard not part of this approval." Simply referencing "10-4 Industrial Services" on the Application for a certificate of zoning compliance, cannot serve as a vehicle for administratively validating a legal nonconforming use.

As found by the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, the current use of the property cannot be sanctioned, based upon the May 6, 2008 Certificate of Zoning Compliance. USE OF THE PROPERTY BY ITS CURRENT OWNER REPRESENTS AN EXPANSION OF THE PREEXISTING NONCONFORMING USE AS A CONTRACTOR STORAGE YARD The Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals found that the current use of 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street represents an illegal expansion of a nonconforming use. This determination finds ample, and overwhelming support in the record. In determining whether an activity is legally nonconforming, or whether the current activity constitute an impermissible expansion of a nonconforming use, three factors must be considered: 1) the extent to which the current use reflects the nature and purpose of the original use, 2) any differences in the character, nature and kind of the use involved, and 3) any substantial differences in the effect upon the neighborhood resulting from differences in the activities conducted on the property. Bauer v. Waste Management CT Page 772-P of Connecticut, Inc., 234 Conn. 221, 236-37 (1995). It is a general, well-established principle of zoning law that nonconforming uses should be abolished, or reduced to conformity as quickly as the fair interest of the parties will admit. In no case, should they be permitted to increase. Hyatt v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 163 Conn. 379, 382 (1972); Raffaele v. Planning & Zoning Board of Appeals, 157 Conn. 454, 462 (1969); McMahon v. Board of Zoning Appeals, 140 Conn. 433, 440 (1953). The record reveals that immediately prior to the Plaintiff's purchase of the property in August of 2007, the former owner, Michael Infante, received a Certificate of Zoning Compliance. The certificate stated that the use of the property was for a "two family dwelling, with office, storage of building equipment, materials, dump trucks and excavating equipment including loaders and shovels." The certificate also includes a notation: "no work." The parcel was legally conforming as a contractor's storage yard, which did not involve work on the site. The zoning compliance field card stated that the property was a "contractor storage yard." While the Bridgeport Zoning Regulations do not define "storage," Black's Law Dictionary provides a common sense definition: "storage," keep (goods, etc.) in safe keeping for future delivery in an unchanged condition." An appropriate definition of the verb "To Store" is found in another respected dictionary: "to place or leave in a lotion (as a warehouse, library or computer memory) for preservation or later use or disposal." (Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (10th Ed. 2001)).

The May 6, 2008 application for a certificate of zoning compliance represents a subtle, but significant shift away from the use of the parcel as a contractor's storage yard. For the first time, the phrase "Auto and truck salvage metal and CT Page 772-Q building material salvage . . ." (Emphasis added) appears. A hand written notation "automotive scrap/junk yard would need P&Z Approvals" provides some restraint. No application was made to the Bridgeport Planning and Zoning Commission for such approval, nor was a Special Permit or Site Plan review initiated. The March 19, 2009 application for a certificate of zoning compliance, filed by Lajoie's Auto Wrecking Company, Inc., states a proposed use of "buying and selling scrap metals." This is the first indication of any trade or commerce taking place on the subject property. Once, again, no Special Permit or Coastal Area Management (CAM) Site Plan Review was sought. Following the zoning reclassification which was effective January 1, 2010, the Plaintiff asked for permission to erect a sign on the property, in conjunction with use of the property as a "scrap metal recycling center." This was followed by a March 10 Application for Certificate of Zoning Compliance in preparation for the opening of the business (ROR 25). Advertisements, published in the Connecticut Post, described the business as "Lajoie's Scrap Metal Recycling, Bridgeport, CT." (ROR 25.) The record supplies no supports for the claim that the use of the property as observed by the zoning enforcement official in August of 2010, existed prior to the change in the zoning regulations in January 1, 2010. As previously noted, it is a cardinal principle of land use policy, that nonconforming uses should be reduced to conformity where possible and should not be permitted to expand in any case. Hyatt v. Zoning Board of Appeals, supra, 382. The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, has disemboweled that rule of law, and tossed it upon the scrap heap it now claims is entitled to legal sanction as a nonconforming use. While this court recognizes that a mere increase in the amount of business done pursuant to a nonconforming use is not an illegal expansion of the original use; Zachs v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 218 Conn. 324, 331 (1991); in this situation, the nature and purpose of the original use as a contractor's CT Page 772-R storage yard bears little or no resemblance to the observations documented by Neil Bonney during his site inspections in August of 2010. Furthermore, the use of the property by the current owner, as catalogued by the zoning enforcement officer and reinforced at the public hearing, has a devastating and unhealthy

impact upon the neighborhood, which a passive contractor's storage yard does not produce. The Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals found the activities "detrimental to the general health safety and welfare," and went so far as to label the situation a "nuisance." In a situation in which the zoning laws and zoning officials of a municipality cannot or will not provide relief from such conditions, an affected neighborhood may resort to civil remedies in the form of a private nuisance action, as an alternative means of seeking the elimination of the offending conditions. Pesty v. Cushman, 259 Conn. 345, 360-61 (2002). In evaluating a situation to determine whether a given use involves an expansion of a preexisting nonconforming use, courts have utilized a "known in the neighborhood" test. Helicopter Associates, Inc. v. Stamford, supra, 713. In applying this test, courts look to the actual use of the land, not merely its contemplated use. Melody v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 158 Conn. 516, 520 (1969); Wallingford v. Roberts, 145 Conn. 682, 684 (1958). The evaluation regarding utilization of the premises is based upon actual use in the neighborhood, rather than decisions reached in private meetings, prior to over the counter approvals being secured. The substantial change visited upon this East End neighborhood by the increase in the use of the property is irrefutable. A contractor storage yard, with minimal off-site impact, has morphed into a facility which accepts metal, cuts and separates metal, and trucks metal off the site through narrow streets, while producing intensive noise and generating off-site pollutants. CT Page 772-S Applying the known in the neighborhood test, supports the conclusion of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, which found that an expansion of a nonconforming use had occurred. Given the rule prohibiting expansions of nonconforming uses, courts have carefully scrutinized any change in use, to determine whether it involves a mere intensification, or is an expansion of a use. In Salerni v. Scheuv, 140 Conn. 566 (1954), the Plaintiff sought a full liquor permit on property where a restaurant with a beer permit was a lawful nonconforming use. The court found this full liquor permit to be an expansion of a nonconforming use, even though both uses involved the sale of food and alcoholic beverages. Salerni v. Scheuv, supra, 571-72. In a similar vein, conversion of summer cottages to year-round use has been found an expansion of a nonconforming use; Cummings v. Tripp, 204, Conn. 67, 85-86 (1986); and adding additional parking made possible by the acquisition of property next to a nonconforming use was not permitted. Raffaele v. Planning & Zoning Board of Appeals, supra, 462.

Here, the preexisting nonconforming use is that of a contractor storage yard. On a contractor storage yard, wood, metal and heavy equipment, including claws of the type observed on August 20, 2010 are stored. Such items are routinely retained on the site. However, the presence of wood on a contractor storage yard would not justify operating a lumber yard, where wood is cut, received, transformed, and sold at retail or wholesale. The presence of trucks on a contractor storage yard does not authorize the use of the premises as a truck rental business, or a used car lot where motor vehicles are brought on to the site for purposes of sale or trade. Likewise, the ability to store metals on a contractor storage yard may not be extended to a use which buys and sells metals, crushes metals, cuts them, moves them with heavy equipment, and trucks the metal off-site to a facility in Norwalk. A nonconforming use enabling a property owner to store metal cannot be contorted to sanction the presence on the site of a metallic Mount Trashmore, which towers over CT Page 772-T the neighborhood. There can be no creditable claim that the use of 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street by the current owner is a lawful, nonconforming use. The Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals properly found that the use of the property constitutes an expansion of a nonconforming use. THE APPEAL FILED BY THE INTERVENING DEFENDANTS MUST BE SUSTAINED The Intervening Defendants have filed a cross appeal dated July 22, 2011. The appeal was amended, with the consent of the Defendant Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, on January 24, 2012. An answer was filed on January 26, 2012. The Interveners claim that a portion of the decision of the Bridgeport Zoning Board Appeals is subject to misinterpretation, or conjecture. They hypothesize that Section II, paragraph 5, might be read to state that a Certificate of Zoning Compliance was issued, authorizing the buying and selling of scrap metal on the site. The paragraph reads: 5. The certificates of zoning compliance issued to the current owner were limited to storage. The March 19, 2008 was limited to "buying and selling scrap metals." The May 6, 2009 Certificate of Zoning Compliance field card stated the property was for "Storage only." "No work incidental to truck/equip. storage 7 scrap metals." On March 10, 2010, the Certificate of Zoning Compliance issued to Lajoie's was for "truck and equipment storage and scrap metal (storage only) (emphasis added).

A search of the record reveals that the only activity on March 19 was an application for a certificate of zoning compliance. The date, however, is March 19, 2009, not 2008. The portion of paragraph 5 which reads: "the March 19, 2008" was limited to "buying and selling scrap metals" is not a complete sentence. The phrase "certificate of zoning compliance" does not appear in the language. It is clear that the proper reference is to March 19, 2009, based on the record. The reference was to an application for a certificate of zoning compliance. To the extend that paragraph 5 could be interpreted as a finding that the buying and selling of scrap metal at 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street was ever authorized, the cross appeal is sustained. The record demonstrates beyond a question, CT Page 772-U that the buying and selling of scrap metal was never authorized, and cannot be sanctioned as a pre-existing nonconforming use. POSSIBLE FUTURE ACTIONS DISCUSSED Although it is not necessary to consider hypothetical future actions in the determination of this appeal, the court notes that the Defendant, Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, in its decision, looked to the future, and not simply the past. The Board stated: "Appellant can either comply with zoning enforcement order or apply to the planning and zoning commission for a special permit under the MU-LI Zoning Regulations or apply to the ZBA for a variance." It should be clear, that compliance with the Cease and Desist Order is in no way contingent upon future action by any land use body in the City of Bridgeport. The dismissal of this appeal will result in a binding order, not an election of remedies. At trial, counsel for the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals acknowledged that the current use of the property is not a permitted use in an MU-LI zone. Therefore, before any Special Permit may be requested (accompanied by a Coastal Area Management (CAM) Site Plan) a use variance, approved by a super majority of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, must be obtained. Any such variance would seem to be problematic. Before a Zoning Board of Appeals can grant a variance, two conditions must be fulfilled: 1) the variance must be shown not to affect substantially the comprehensive plan, and 2) adherence to the strict letter of the zoning ordinances must be shown to cause unusual hardship, unnecessary to the carrying out of the general purposes of the zoning plan. Francini v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 228 Conn. 785, 790 (1994); Smith v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 174 Conn. 323, 326 (1978). The comprehensive plan consists of the

zoning regulations, and the zoning map. Burnham v. Planning & Zoning Commission, 189 Conn. 261, 267 (1983). In this case, because a request for a CT Page 772-V use variance would seek authorization to use the property for a use which is not permitted in an MU-LI zone, it might be determined that any use variance would be inconsistent with the comprehensive plan. A zoning board of appeals is without power to grant a variance, where the granting of the variance would impair the integrity of the comprehensive plan. Whitaker v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 179 Conn. 650, 656 (1980); Parsons v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 140 Conn. 290, 295 (1953). A finding of hardship is even more tenuous. By definition, a variance constitutes permission to act in a manner which, without the variance, would be prohibited by the zoning ordinances of the municipality. Burlington v. Jencik, 168 Conn. 506, 508 (1975). Therefore, an applicant must show, that because of some peculiar characteristics of his property, the strict application of the zoning regulations produces a hardship, not affecting other properties in the zone. Dolan v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 156 Conn. 426, 430 (1968). Any hardship must be imposed by conditions outside the property owner's control. Norwood v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 62 Conn.App. 528, 533 (2001). If the hardship is self-inflicted, arising out of the voluntary act of the applicant, the board does not have the authority to grant a variance. Pollard v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 186 Conn. 32, 39 (1982). Hardships which are personal to the applicant do not provide sufficient grounds for the granting of a variance. Gangemi v. Zoning Board of Appeals, 54 Conn.App. 559, 564 (1999). CT Page 772-W Future possibilities should have no affect upon the city's efforts to ensure compliance with the Cease and Desist Order issued by Zoning Enforcement Official Bonney. Nor should future applications deter the City of Bridgeport from pursuing all remedies available to it, in order to bring about swift compliance with its zoning regulations. CONCLUSION AND ORDER The appeal of the Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, is DISMISSED. The cross appeal, filed by the Intervening Defendants, is SUSTAINED. The Plaintiff, 301 Eagle Street, LLC, is ordered, consistent with the findings of the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals, to immediately cease and desist from the buying and selling of scrap metal on the premises, and from the separating, crushing, and the cutting of metals on the premises, since those activities constitute an illegal expansion of the nonconforming use of the property as a contractor storage yard.

The Plaintiff is further ordered to remove its mountains of metal from the property, as depicted in the photographs presented to the Bridgeport Zoning Board of Appeals. Although the storing of metal is a nonconforming use incident to the operation of a contractor's storage yard, the material currently being stored on the property is not being stored consistent with the preexisting nonconforming use of the property as a contractor's storage yard. The Plaintiff is ordered to cease and desist from the weighing, packaging and containerizing of scrap metal on the property, except such as may be necessary to effect the removal of the offending piles of scrap metal. The Plaintiff is further ordered not to transport any additional scrap metal or similar materials to the property at 291-301 and 321 Eagle Street, except as may be incidental to the maintenance on the property of a contractor's storage yard. Although heavy equipment may be stored on the property, the Plaintiff is ordered to cease and desist from operating the heavy equipment on the property, except as may be necessary to remove from the property the piles of scrap metal and debris which were revealed in the August 2010 on-site inspections.

* Syllabi and Procedural History, 2009 Connecticut Secretary of State. Compilation 2009 Loislaw.com, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- List of Fatigue Standards and Fracture Standards Developed by ASTM & ISOДокумент3 страницыList of Fatigue Standards and Fracture Standards Developed by ASTM & ISOSatrio Aditomo100% (1)

- DJI F450 Construction Guide WebДокумент21 страницаDJI F450 Construction Guide WebPutu IndrayanaОценок пока нет

- Multi Organ Dysfunction SyndromeДокумент40 страницMulti Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDr. Jayesh PatidarОценок пока нет

- Flow Zone Indicator Guided Workflows For PetrelДокумент11 страницFlow Zone Indicator Guided Workflows For PetrelAiwarikiaar100% (1)

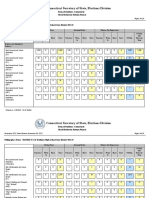

- Danbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Документ91 страницаDanbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Документ91 страницаDanbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Документ91 страницаDanbury November 2023 Municipal Election Returns (Amended)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Multi Pressure Refrigeration CyclesДокумент41 страницаMulti Pressure Refrigeration CyclesSyed Wajih Ul Hassan80% (10)

- St. Hiliare v City of Danbury (complaint)Документ91 страницаSt. Hiliare v City of Danbury (complaint)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- 3 Lake Ave Extension LLC V City of Danbury Zoning Commission JudgementДокумент36 страниц3 Lake Ave Extension LLC V City of Danbury Zoning Commission JudgementAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Roberto Alves SEEC 20 January 10 (Termination)Документ31 страницаRoberto Alves SEEC 20 January 10 (Termination)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Re-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 January 10Документ29 страницRe-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 January 10Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Re-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC Form 20 October 10 2022Документ32 страницыRe-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC Form 20 October 10 2022Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Alves For Danbury SEEC 20 April 10 2023Документ201 страницаAlves For Danbury SEEC 20 April 10 2023Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Re-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 April 10 2023Документ88 страницRe-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 April 10 2023Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Alves For Danbury SEEC 20 July 10 2023Документ102 страницыAlves For Danbury SEEC 20 July 10 2023Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Summary Ballots by Party 2021Документ6 страницSummary Ballots by Party 2021Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Re-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 October 10 2023Документ75 страницRe-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC 20 October 10 2023Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Re-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC Form 20 January 10 2023Документ54 страницыRe-Elect Mayor Esposito SEEC Form 20 January 10 2023Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Alves For Danbury Form 20 January 10Документ37 страницAlves For Danbury Form 20 January 10Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- To City of Danbury Election WardsДокумент13 страницTo City of Danbury Election WardsAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Governor Lamont Nominates 20 Jurists To Serve As Judges of The Connecticut Superior CourtДокумент5 страницGovernor Lamont Nominates 20 Jurists To Serve As Judges of The Connecticut Superior CourtAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury 2022 Head Moderators ReturnsДокумент7 страницDanbury 2022 Head Moderators ReturnsAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- 2022 Danbury Head Moderators Return DataДокумент118 страниц2022 Danbury Head Moderators Return DataAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury Republican Party Ward Reapportionment Proposal (Plan B)Документ8 страницDanbury Republican Party Ward Reapportionment Proposal (Plan B)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- 2021 Danbury Head Moderator Return DataДокумент136 страниц2021 Danbury Head Moderator Return DataAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- 2021 Danbury Election Finals (Per Ward)Документ2 страницы2021 Danbury Election Finals (Per Ward)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury 2021 Election TotalsДокумент9 страницDanbury 2021 Election TotalsAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Danbury Democrats Ward Reappointment Proposal (Plan A)Документ6 страницDanbury Democrats Ward Reappointment Proposal (Plan A)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Joe DaSilva For Judge of Probate, Danbury CT 2022Документ2 страницыJoe DaSilva For Judge of Probate, Danbury CT 2022Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Dean Esposito Form 20 October 26 (7 Days Until Election)Документ40 страницDean Esposito Form 20 October 26 (7 Days Until Election)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Summary Ballots by Party 2021Документ6 страницSummary Ballots by Party 2021Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Frank Salvatore City Council at Large MailerДокумент2 страницыFrank Salvatore City Council at Large MailerAlfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Alves For Danbury Form 20 October 26 (7 Days Until Election)Документ35 страницAlves For Danbury Form 20 October 26 (7 Days Until Election)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- Alves For Danbury Form 20 October 12 Amendment (7 Days Until Election)Документ4 страницыAlves For Danbury Form 20 October 12 Amendment (7 Days Until Election)Alfonso RobinsonОценок пока нет

- BIO 201 Chapter 11 LectureДокумент34 страницыBIO 201 Chapter 11 LectureDrPearcyОценок пока нет

- Welcome To Our 2Nd Topic: History of VolleyballДокумент6 страницWelcome To Our 2Nd Topic: History of VolleyballDharyn KhaiОценок пока нет

- Gujral FCMДокумент102 страницыGujral FCMcandiddreamsОценок пока нет

- Project ReportДокумент14 страницProject ReportNoah100% (7)

- Child DevelopmentДокумент15 страницChild Development4AndreeaОценок пока нет

- Keyword 4: Keyword: Strength of The Mixture of AsphaltДокумент2 страницыKeyword 4: Keyword: Strength of The Mixture of AsphaltJohn Michael GeneralОценок пока нет

- 1 Circuit TheoryДокумент34 страницы1 Circuit TheoryLove StrikeОценок пока нет

- GSD Puppy Training Essentials PDFДокумент2 страницыGSD Puppy Training Essentials PDFseja saulОценок пока нет

- Presentation AcetanilideДокумент22 страницыPresentation AcetanilideNovitasarii JufriОценок пока нет

- Recruitment and Selection in Canada 7Th by Catano Wiesner Full ChapterДокумент22 страницыRecruitment and Selection in Canada 7Th by Catano Wiesner Full Chaptermary.jauregui841100% (51)

- Statics: Vector Mechanics For EngineersДокумент39 страницStatics: Vector Mechanics For EngineersVijay KumarОценок пока нет

- Case 445Документ4 страницыCase 445ForomaquinasОценок пока нет

- WeeklyДокумент8 страницWeeklyivaldeztОценок пока нет

- 500 TransДокумент5 страниц500 TransRodney WellsОценок пока нет

- Scholomance 1 GravitonДокумент18 страницScholomance 1 GravitonFabiano SaccolОценок пока нет

- Principles Involved in Baking 1Документ97 страницPrinciples Involved in Baking 1Milky BoyОценок пока нет

- 23001864Документ15 страниц23001864vinodsrawat33.asiОценок пока нет

- Manuscript FsДокумент76 страницManuscript FsRalph HumpaОценок пока нет

- Asaali - Project Estimation - Ce155p-2 - A73Документ7 страницAsaali - Project Estimation - Ce155p-2 - A73Kandhalvi AsaaliОценок пока нет

- Ap, Lrrsisal of Roentgenograph, Ic: I SsayДокумент30 страницAp, Lrrsisal of Roentgenograph, Ic: I SsayMindaugasStacevičiusОценок пока нет

- EDS-A-0101: Automotive Restricted Hazardous Substances For PartsДокумент14 страницEDS-A-0101: Automotive Restricted Hazardous Substances For PartsMuthu GaneshОценок пока нет

- Management of DredgedExcavated SedimentДокумент17 страницManagement of DredgedExcavated SedimentMan Ho LamОценок пока нет

- FactSet London OfficeДокумент1 страницаFactSet London OfficeDaniyar KaliyevОценок пока нет

- OPTCL-Fin-Bhw-12Документ51 страницаOPTCL-Fin-Bhw-12Bimal Kumar DashОценок пока нет

- Investigation of Skew Curved Bridges in Combination With Skewed Abutments Under Seismic ResponseДокумент5 страницInvestigation of Skew Curved Bridges in Combination With Skewed Abutments Under Seismic ResponseEditor IJTSRDОценок пока нет