Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Bertucci-Tamaño Del Grupo y Logro

Загружено:

Rebeca GrunfeldИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Bertucci-Tamaño Del Grupo y Logro

Загружено:

Rebeca GrunfeldАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Journal of General Psychology, 2010, 137(3), 256 272 Copyright C 2010 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

The Impact of Size of Cooperative Group on Achievement, Social Support, and Self-Esteem ANDREA BERTUCCI STELLA CONTE DAVID W. JOHNSON ROGER T. JOHNSON University of Minnesota ABSTRACT. The effect of cooperative learning in pairs and groups of 4 and in ind ividualistic learning were compared on achievement, social support, and self-esteem. Sixty-tw o Italian 7th-grade students with no previous experience with cooperative learning were assigned to conditions on a stratified random basis controlling for ability, gen der, and selfesteem. Students participated in 1 instructional unit for 90 min for 6 instructional day s during a period of about 6 weeks. The results indicate that cooperative learning in pairs and 4s promoted higher achievement and greater academic support from peers than did individualistic learning. Students working in pairs developed a higher level of social self-este em than did students learning in the other conditions. Keywords: cooperation, group size, self-esteem, social support THE PRESENT STUDY EXAMINES THE EFFECTS OF GROUP SIZE on three variables: academic achievement, social support, and self-esteem. An important aspect of this study was that the participants had never participated in a coope rative learning lesson before. They represent a uniquely naive sample. Almost all the previous research has been conducted with participants who were experienced with cooperative learning and, therefore, brought the attitudes and emotions fro m previous experience to their participation in the research. This study is one of the few to examine the relative effectiveness of cooperative learning with participa nts who are unencumbered by previous cooperative learning experiences. Address

correspondence to David W. Johnson, University of Minnesota, 60 Peik Hall, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; johns010@umn.edu (e-mail). 256

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 257 Academic Achievement The first issue studied was the impact of size of group on academic achievement. Social interdependence theory predicts that cooperative groups will have higher achievements than individuals working competitively or individualisticall y (Deutsch, 1962; Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989). The theory does not consider the size of the group important (i.e., whether cooperat ive groups have two or 20 members, they will outperform individuals working alone), although conditions mediating the relationship between social interdependence and achievement include the level of members interpersonal and small-group skills. The theory thus implies that as the size of the group increases, the nee d for members to be skilled in coordinating their efforts also increases. A number of researchers, however, have posited that group size is an important variable influencing group productivity. There is somewhat of a long-standing paradox concerning the impact of group size on productivity and effectiveness (Johnson & F. Johnson, 2009; Johnson & R. Johnson, 1999), with some researchers concluding that group productivity increases as group size increases, and other researchers concluding that group productivity decreases as group size increases. Productivity Increases as Size Increases One side of the paradox is the issue that as group size increases, so do the res ources available and, therefore, so does group productivity. There are researchers who believe that the size of the cooperative group has a positive impact on the level of achievement of group members (Seta, Paulus, & Schkade, 1976; Thor, 1976). As the size of a group increases, so do the range of abilities, expertise, skill s, and the number of minds available for acquiring and processing information. Thor (1976) compared the achievement of students working alone, in pairs, and in tria ds. He found groups of three outperformed groups of two and single individuals, and groups of two outperformed single individuals. The larger the group, the more ea ch member learned. Seta, Paulus, and Schkade (1976) compared cooperative versus competitive efforts in groups of two and four on a coaction task (i.e., particip ants did the task on their own without discussion). Groups of four performed higher than groups of two in the cooperative condition. On the basis of these studies, it may be expected that groups of four will outperform groups of two and individual

s working alone, and groups of two will outperform individuals working alone. Productivity Decreases as Size Increases The other side of the paradox is the fact that as the size of the group increase s, the difficulties in coordinating members behavior and using their resources also increase and, therefore, the less productive the group tends to be. Perfecting teamwork is a prerequisite for completing taskwork. Taskwork is the academic

258 The Journal of General Psychology assignment the students are working to complete. Teamwork is the procedural knowledge, proficiencies, skills, and attitudes required to organize and coordin ate the efforts of group members. The larger the group, the more complex the teamwor k tends to be. When individuals work by themselves, for example, there are no social interactions to manage. When individuals work in pairs, however, there ar e two social interactions (i.e., sending and receiving) to manage. When individual s work in triads, there are six social interactions to manage. When individuals wo rk in fours, there are 12 social interactions to manage. Thus, the larger the group , the more complex the teamwork, and the longer it may take for a group to be productive and cohesive (Bales & Strodtbeck, 1951; Ortiz, Johnson, & Johnson, 1996). There are at least three aspects of teamwork that affect how quickly memb ers of groups outperform individuals working alone. They are members level of group skills, the interference between teamwork and taskwork, and the degree of members social loafing. Perhaps the most central aspect of teamwork is members level of social skills. The larger the group, the more skillful group members must be in such things as providing everyone with a chance to speak, coordinating the actions of group members; reaching consensus; ensuring, explaining, and elaborating the material being learned; keeping all members on task; and maintaining good working relatio nships among members (Johnson & F. Johnson, 2009). Many students do not have the social skills needed for effective group functioning even for small gro ups and, therefore, they have to be trained. Lew, Mesch, Johnson, and Johnson (1986) found that social skills training increased members academic achievement over that of individuals working alone. Wegerif, Mercer, and Dawes (1999) found that individual results on a standard nonverbal reasoning test significantly improved as a result of being taught how to engage in exploratory talk during group meetings . Webb and Farivar (1994) found that training and practice in both basic communica tion and helping skills resulted in higher achievement than did training in basic communications skills only. Overall, the more social skills training group members receive, the more effective the group tends to be. Training in social skills has a cost. It focuses attention on teamwork at the expense of taskwork. Trying to learn teamwork skills while doing taskwork may cause attention overload. Attention overload occurs when individuals try to attend

to more things than he or she has the capacity to process. When people are bombarded with attentional demands, their focus of attention actually shrinks (e .g., Geen, 1976, 1980). In the case of group productivity, the need to simultaneously attend to teamwork and taskwork causes members attention to shrink and a deterioration of taskwork efforts results. Another aspect of teamwork is the degree to which all members contribute their resources to the group effort. Social loafing tends to increase as the siz e of the group increases. Stephan and Mishler (1952) found that the proportion of active speakers in discussion groups declined with group size. They differentiat ed between the functional size of the group and the actual size of the group. As gr oups

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 259 get larger, there is a tendency for fewer members to try actively to contribute to the joint efforts (Watson & Johnson, 1972), and members are less likely to see their own contribution as being important to the group s chances of success (Kerr, 1989; Olson, 1965). Morgan, Coates, and Rebbin (1970) found that team performance actually improved when one member was missing from five-person teams, perhaps because members believed their contributions were more necessary. Fox (1985) found that as the size of the group increases, the difficulties increase in moni toring members behavior to detect norm violations and apply meaningful sanctions. The smaller the group, the more visible members efforts and thereby the greater their accountability. Given the problems of group members level of social skills, the interference between teamwork and taskwork, and the degree of members social loafing, it may be expected that as the size of the group increases, the lower the group members achievement will be. The issue of which of these two expectations is valid will be explored in this study. Social Support The second issue investigated is the effect of size of cooperative group on social support. An advantage of working in cooperative groups over working alone is that group members may provide each other with social support, both academica lly and personally. Past research indicates that in cooperative situations, more social support is experienced from peers than students experience in individuali stic and competitive situations (Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989). There has been little if any research on how social support from peers is affected by the size of a group. It may be that having a relationship w ith three peers may result in a person feeling more support than a relationship with only one peer. Conversely, with increasing group size, there is a decrease in th e amount of interaction among group members and a few participants are likely to dominate, whereas others may remain passive (Watson & Johnson, 1972). The likely result may be a potential reduced group cohesion, fewer friendships, and less personal support among members. The results of this study may provide some clarification of whether group size increases or decreases social support. Self-Esteem The third issue investigated is the impact of group size on self-esteem. There has been little if any research on the impact of size of group on self-esteem. Typically, cooperative experiences tend to result in higher self esteem than doe s working alone (Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989).

Many of the studies on cooperation and self-esteem, however, did not use standar dized measures of self-esteem and often focused on only one aspect of self-esteem. In this study, a standardized measure focusing on several aspects of self-esteem

260 The Journal of General Psychology was used (i.e., the Multidimensional Self Concept Scale [(MSCS; Bracken, 1992]). Three of the scales are possibly affected by cooperative learning experiences, s ocial self-esteem, competence, and academic self-esteem. It might be expected that all three types of self-esteem would be higher in a group of four because three people have the opportunity to give a student positive feedback and express thei r positive regard. However, more may not be better. It may be that working in a pair will increase self-esteem more than working in a group of four, because the relationship will be more personal and individuals will know each other better. The results of this study may clarify this issue. Summary The purpose of the present study is to investigate the effect of group size on individual achievement, social support, and self-esteem. In social interdependen ce theory, the size of the group is assumed not to matter in terms of cooperation promoting higher achievement than individualistic efforts. There are researchers , however, who do believe members achievement will increase as the size of the group increases; and there are others who believe that members achievement will decrease as the size of the group increases. In addition, some researchers belie ve there will be more social support in larger groups and others who believe the opposite. Finally, there are researchers who believe that self-esteem will be hi gher in larger groups and those who believe that self-esteem will be higher in smalle r groups. The results of this study will hopefully add some clarity to these issue s. Method Participants There were 62 seventh-grade middle-school students in Italy, with no experience in cooperative learning activities, who participated in this study. The sample consisted of 31 males and 31 females. Before assigning students to the experimen tal and control conditions, IQ was assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised (WISC-RL; Wechsler, 1997) to verify that no students in th e sample had cognitive deficits. All students in the sample were of normal intelli gence or above. Students were randomly assigned to conditions. Eighteen students (9 males and 9 females) were assigned to the individualistic learning condition,

20 students (10 males and 10 females) were assigned to the cooperative learning in pairs condition, and 24 students (12 males and 12 females) were assigned to t he cooperative learning in groups of four condition. The gender, IQ, and self-estee m of the students were balanced in the three conditions. An almost-equal number of students from each class were randomly assigned to conditions to control for any teacher effects.

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 261 Independent Variable The independent variable was cooperative versus individualistic learning. There were two cooperative conditions, pairs and groups of four. Students were randomly assigned to conditions. Students assigned to the individualistic learni ng condition followed the four-step procedure by themselves, working in their own desks and not interacting with the other students in the class. They were given the individualistic goal of mastering the assigned material. Cooperation was structured by a combination of goal and task interdependence. For goal interdependence, students were told to work together cooperatively and ensure that all group members learned the assigned material. Task interdependence was structured by having the students alternate in performing each step of the procedure and then to switch the steps for the next paragraph. Students assigned to the cooperative learning conditions were also told to work together to learn the material and help groupmates learn the material, cooperate with the other members of the group, and respect the four-step procedure. Studen ts assigned to the cooperative pairs condition were instructed to alternate perform ing each step of the procedure and to rotate responsibilities after every paragraph. For the first paragraph, for example, Student 1 performed Steps A and C, and Student 2 performed Steps B and D. For the second paragraph, Student 1 performed Steps B and D, and Student 2 performed Steps A and C. They kept switching the steps for each paragraph until they covered all the material. Students assigned to the cooperative groups of four condition were instructed to perform one of the four steps for each paragraph and rotate the steps so that after four paragraphs, each grou p member had performed each of the steps. Student 1 performed Step A, Student 2 performed Step B, Student 3 performed Step C, and Student 4 performed Step D. For the next paragraph, Student 1 performed Step B, Student 2 performed Step C, Student 3 performed Step D, and Student 4 performed Step A. During a lesson, each group member performed each step at least twice. Dependent Variables There were three dependent variables in this study. The first was achievement. The subject matter studied was two sessions on smoking, two sessions on alcohol abuse, and two sessions on drug abuse. An achievement test was given at the end of the second, fourth, and sixth sessions. Each test consisted of 20 questions o n the content studied. Test 1 was on the risks and damages of smoking, Test 2 was on the risks and damages of using alcohol, and Test 3 was on the risks and damages of drug use. The tests were developed by the teachers and the researcher involve d in the study.

The second dependent variable was peer personal and academic support measured by the Classroom Life Measure (Johnson & R. Johnson, 1996; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1983; Johnson, Johnson, & Anderson, 1983). The Student Academic

262 The Journal of General Psychology Support scale consists of four items that measured students beliefs that classmat es care about how much one learns and wishes to help one learn. The Cronbach Alpha for this scale was 0.67. The Student Personal Support scale consisted of five it ems that measured students belief that classmates care about and like one as a person . The Cronbach alpha for this scale was 0.78. Two bilingual social scientists indi vidually translated the questions and all other material that was originally written in English into Italian and then compared translations. An item or sentence was not considered translated until both the bilingual researchers reached agreement on the translated version (Brislin, 1970). A third bilingual social scientist th en translated the items and sentences back into English to ensure that they matched the original questions. All items were written to fit into a 5-point Likert-scal e format (from strongly disagree to strongly agree ). The third dependent variable was self-esteem. Self-esteem was measured by the MSCS (Bracken, 1992). Students responded on a 5-point Likert-type rating scale to each question. The social self-esteem, competence, and academic self-esteem scales were used to compare the impact of cooperative versus individ ualistic learning. Although the scales are intercorrelated, they are sufficiently independent to be treated as unique domains. The MSCS was normed on a sample for which the ages ranged from 9 years to college age; participants represented 17 cities in each of the major regions of the United States. Social Self-Concept is the sum of the individual s feelings regarding his or her social self. Internal consistency was reported at .90. Test-retest reliability at 4 weeks was estimate d at .79. The Competence scale of the MSCS measures an individual s generalizations about his or her competence resulting from attempts to solve problems, attain goals, produce desired outcomes, and function effectively. Internal consistency for this scale was reported at .87. Test-retest reliability at 4 weeks was estim ated at .76. The Academic Self-Concept Scale measures the sum of the individual s feelings regarding total academic functioning. Internal consistency was reported at .91. Test-retest reliability at 4 weeks was estimated at .81. Overall, the MS CS is supported as an assessment tool for self-concept (Murphy, Impara, & Plake, 1999). The MSCS scales used have an equal number of positively and negatively worded items. For example, the first item is positively worded: I am usually a lo t of fun to be with. The second item is an example of an item that is negatively worded: People do not seem to be interested in talking with me. Negatively worded items are reverse scored so that higher point values are awarded when the

student disagrees with negative statements. High scores indicate high self-conce pt, and low scores indicate lower self-concept. Procedure The present study compared individualistic learning with cooperative learning in groups of two and four on three curriculum units focusing on alcohol, tobacco, and drug abuse. Each unit consisted of two instructional sessions, each

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 263 lasting 90 min, and one test. Before the study, students were tested on their knowledge on alcohol, smoking, and drug abuse to verify that the material to be taught was unknown to them. Any concepts that the students already knew were eliminated from the curriculum units to ensure that participants studied on ly new content during the instructional sessions. Students were randomly assigned to conditions, stratifying for ability, gender, class, and self-esteem. Each con dition was assigned a separate classroom comparable in size. Four teachers participated in the study and were rotated across conditions. During the four days a week that participants and teachers were not involved in the study, they studied the normal curriculum without using cooperative learning. The normal instructional method was whole class, direct instruction. The contents of the instructional un its were related to health education and were identical across the three conditions. The topic of the first two lessons was the risks and damages from smoking, the topic of lessons three and four was the risks and damages from drinking alcohol, the topic of lessons five and six was the risks and damages from using drugs. The six learning sessions were conducted one week apart and were held on the same day each week. Each condition met in a different classroom. Each session was 90 minutes long and began with a 10-minute introduction by the teacher concerning the topic of the lesson and about how students assigned to the different experimental conditions were expected to work. In each condition, students were instructed to (a) read the assigned material, one paragraph at the time; (b) explain the content of the paragraph in their own words; (c) generate a question about the principal point(s) of the paragraph; and (d) answer the question. Sessions 2, 4, and 6 ended with a 20-question achievement test on the instructional unit. The tests were taken individually at the end of the each instructional unit (smoking, alcohol, and drugs). Students were told to complete the test alone without interacting with each other. The experimenter randomly observed each condition to ensure the teacher was following the protocol and the students were following the four-step procedure. At the end of the study, students took the MSCS and the social support scales of Classroom Life Measure. Analyses A repeated measure multivariate analysis of variance (RM MANOVA) was conducted to determine the effect of size of the group on achievement. Univariat e analysis of variance (ANOVAs) and planned comparisons were conducted as follow-up tests. Mutivariate analysis of variance (MANOVAs) were also conduct ed to test the effect of size of the group on social support and self-esteem. Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVAs) and planned comparison were conducted as follow-up tests. Eta squared were also calculated to give a measure of the effect sizes.

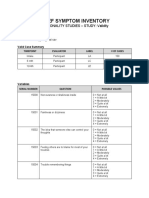

264 The Journal of General Psychology Results Achievement Results are organized by the study s hypotheses. The first variable investigated was achievement (see Table 1). The multivariate F omnibus for the time size of the group interaction was significant (Wilks Lambda =0.669, F(6, 114) =4.229, p < .001, .2 =.13). Concerning session one (lessons one and two), univariate test results showed significant differences between students assigned to experimental conditions (F(2, 59) =3.330, p =.043, .2 =.11). Students assigned to individual and cooperative learning in pairs conditions performed significantly better than students assigned to the cooperative learning in groups of four condition (F(1, 59) =4.26, p =.004, .2 =.07). No significant differences were found between the individual learning condition and the cooperative learning in pairs condition (F (1, 59) =2.19, p =.144, .2 =.038). Concerning session two (lessons three and four), univariate test results showed a significant difference between students assigne d to experimental conditions (F(2, 59) =7.222, p =.002, .2 =.20). Students assigned to the cooperative learning in pairs condition performed significantly better th an student assigned to other conditions (F(1, 59) =13.52, p< .001, .2 =.19). There were no differences between students working individually and in groups of four (F(1, 59) =1.59, p =.213, .2 =.03). Concerning session three (lessons five an d six), univariate test results also showed significant differences between studen ts assigned to experimental conditions (F(2, 59) =4.109, p =.021, .2 =.12). Students assigned to the cooperative learning conditions (pairs and groups of fo ur) TABLE 1. Scores on Achievement on the

Different Sessions and on Total Scores Variable Individuals Pairs Groups of four First unit M SD Second unit M SD Third unit M SD Total M SD 14.22 1.89 13.88 1.18 13.61 1.50 41.72 4.11 15.05 1.93 15.50 1.70 15.15 2.08 45.70 4.72 13.70 1.36 14.41 1.10 14.70 1.45 42.83 3.25 Note. Individuals, n =18; pairs, n =20; groups, n =24.

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 265 performed significantly better than students assigned to the individual conditio n (F(1, 59) =7.69, p =.007, .2 =.12). There were no significant differences between pairs and groups of four (F(1, 59) =0.74, p =.393, .2 =.012). Univariate test results for total scores showed that the difference between experimental conditions is significant (F(2, 59) =5.07, p =.009, .2 =.15). Particularly, students working in pairs obtained higher scores than students working in other conditions (F(1, 59) =9.74, p =.003, .2 =.14). No significant differences were found between students working individually and in groups of four (F(1, 59) =0.78, p =.38, .2 =.013). Social Support The second variable investigated was social support. The dimensions of peer academic support and peer personal support were included in this study (Johnson & Johnson, 1983, 1996; Johnson, Johnson & Anderson, 1983). The results appear in Table 2. The multivariate F omnibus is significant (Wilks Lambda =0.773, F(4, 116) =3.987, p =.005, .2 =.13). Results showed that the univariate F omnibus for the dimension of peer academic support was significant (F(2, 59) =8.546, p =.001, .2 =.23). Particularly, students assigned to the cooperative learning conditions displayed a higher perception of peer academic support than students assigned to the individual learning condition (F(1, 59) =17.09, p < .001, .2 =.22). No significant differences were found between students assigned to th e cooperative learning conditions (F(1, 59) =0.03, p =.867, .2 =.00). Results showed that the univariate F omnibus for the dimension of peer personal support was not significant (F(2, 59) =0.142, p =.868, .2 =.005). Self-Esteem The third variable investigated was self-esteem. The dimensions of social, academic, and competence self-esteem from the MSCS (Bracken, 1992) were TABLE 2. Scores on the Different Dimensions of

the Social Support Scales Variable Individuals Pairs Groups of four Peer academic support M SD Peer personal support M SD 2.77 0.73 3.11 0.67 3.75 0.96 3.25 0.78 3.70 0.91 3.16 0.91 Note. Individuals, n =18; pairs, n =20; groups, n =24.

266 The Journal of General Psychology TABLE 3. Scores on the Different Dimensions of the Self-Esteem Scales Variable Individuals Pairs Groups of four Social M SD Competence M SD Academic M SD 99.33 12.16 93.83 11.51 91.11 21.15 108.90 11.42 95.70 13.61 85.30 22.30 102.87 11.71 93.54 9.84 88.50 20.40 Note. Individuals, n =18; Pairs, n =20; Groups, n =24. measured in this study (see Table 3). The multivariate F omnibus is significant (Wilks Lambda =0.848, F(6, 114) =2.358, p =.022, .2 =.028). Results showed that the univariate F omnibus for the dimension of social self-esteem is significant (F(2, 59) =3.256, p =.046, .2 =.099). Particularly, students working in pairs

displayed a higher social self-esteem than students assigned to the other learni ng conditions (F(1, 59) =5.92, p =.018, .2 =.08). No significant differences were found between students assigned to the conditions of individual and cooperative learning in groups of four (F(1, 59) =0.93, p =.337, .2 =.015). Univariate F omnibus did not show significant differences for competence (F(1, 59) =0.210, p =.812, .2 =.007) and academic self esteem (F(1, 59) =0.358, p =.701, .2 =.02). Discussion This study examined the effects of group size on achievement, social support, and self-esteem. There is considerable evidence that cooperative efforts result in higher achievement than do individualistic efforts (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, 2005). The theory underlying these results is social interdependence theory, whi ch assumes that size of group does not affect the superiority in achievement of cooperation over competitive and individualistic efforts (given that members hav e sufficient social skills). There are researchers, however, who believe that size of group does have a significant positive influence on group productivity and researchers who believe that size of group has a significant negative influence on group productivity. The results of this study provide some clarification of this issue. In examining the impact of group size on achievement, the results of this study indicate that members of both cooperative pairs and cooperative groups of four achieved significantly higher than did individuals working alone at the

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 267 end of the study (i.e., measurement point three). These results corroborate the previous research that found that individuals working in cooperative groups tend to achieve higher results than individuals working individually (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, 2005). Thus, at the end of the study, group size did not seem to influence the relationship between cooperation and achievement. In this study, however, achievement was also measured at one-third and two-thirds points in the study. This allows a more detailed analysis of the effect of group size on achievement (see Figure 1). The point of view that achievement would increase as the size of the group increased is based on the view that as more members are added to the group, the resources for achieving the group s goals also increase. The more resources available, the higher the achievement should be (Seta, Paulus, & Schkade, 1976; Thor, 1976). The results of this study do not support this point of view. Studen ts in the groups of four did not achieve higher results than students working in pa irs. From Figure 1, the view that achievement would decrease as the size of the group increases was supported by the results of the first test, on which partici pants in the individualistic condition achieved higher results than participants in th e cooperative groups of four condition. These results may be somewhat misleading. The participants in the individualistic condition were probably quite skilled in working alone, having done so for their entire school lives. The participants in the groups of four, on the other hand, probably were unskilled in organizing and coordinating the teamwork efforts of group members, as they had no previous expe rience in working in cooperative groups in school. Teamwork involves complex social skills, such as leadership, communication, trust-building, decision makin g, and conflict resolution skills (Johnson, 2009; Johnson & F. Johnson, 2009). It t akes time for participants to learn these skills and to use them appropriately. Learn ing teamwork skills and procedures should take less time in pairs than in groups of four. Thus, on the first test, individuals and groups of two achieved higher res ults than participants working in groups of four. Overall, these results support the view that the larger the group, the more likely the initial organizing of teamwo rk may interfere with completing taskwork, resulting in lower achievement results. As time passes, however, group members tend to become more skilful and more experienced in working together, and teamwork becomes automatic, thus ceasing to be a competing focus of attention to taskwork. Taskwork then tends to proceed effectively and efficiently, and members of a cooperative group tend to achieve higher than do individuals working alone. In Figure 1, by the second test given at the end of session four, participants in the groups of four achieved results of

approximately the same level as the participants working individualistically. On the third test, participants in the groups of four achieved significantly higher results than the individuals working alone. From this data it may be concluded that as groups get larger, a sufficient level of group skills and experience in worki ng together may be needed before participants in the cooperative groups will outper form participants working alone (Ortiz, Johnson, & Johnson, 1996). It should be

268 The Journal of General Psychology Test 3Test 2Test 1 12.012.513.013.514.014.515.015.516.016.5 Cor rect answers Singles Pairs Groups Achievement tests FIGURE 1. Results on achievement tests for the experimental conditions.

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 269 noted, however, that the subject matter did vary for each test, with the first t est being on smoking, the second test being on alcohol, and the third test being on illegal drugs. There is a possibility that it was the subject matter studied and not the development of the group that accounted for the achievement results; but because participants were randomly assigned to conditions, this possibility is very smal l. The teachers, furthermore, made a special effort to make the units equivalent. The results of this study do not confirm the novelty effect, which states that participants who have never worked in cooperative learning groups before will experience increased interest and motivation because it was something new. While the learning situation was novel and different from what they have usually exper ienced, any increase in interest and motivation seems to have been overpowered by the difficulties in mastering teamwork and taskwork simultaneously. The second issue studied was the impact of size of cooperative group on perceived peer academic and personal support. Social support may be aimed at enhancing another person s success (academic social support) or at providing suppo rt on a more personal level (personal social support). It was expected that more peer academic and personal social support would be found in a group of four than in a pair, and more peer academic and personal support would be found in a pair than in individualistic learning. The results of this study, however, found that both working in pairs and fours produced equivalent amounts of academic peer support and that both cooperative conditions resulted in greater peer academic support than did individualistic learning. The results corroborate the previous research on academic social support (Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989). Social support has been found to be related to achievement, successful problem-solving, persistence on challenging tasks under frustrating conditions, retention, lack of cognitive interference during problem solving, attendance or lack of absenteeism, academic and career aspirations, more appropriate seeking of assistance, and greater compliance with regimens and behavioral patterns that increase productivity (Bowlby, 1969; Cohen & Willis, 1985; Johnson, 1981; Johnson & Johnson, 1983; Sarason, Levine, Basham, & Sarason, 1983; Sarason, Sarason, & Linder, 1983; Wallston, Alagna, DeVellis, & DeVillis, 1983). It has also been found to promote physical health, psychological health, and successful coping with stress and adversity (Johnson & F. Johnson, 2009). The many benefits derived from feeling academically supported by peers may be just as available to members of pairs as to members of groups of four. The lack of significant differences on perceived peer personal support contradicts the previous research (Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989). This counter finding may be because of the short history of working together in the cooperati ve groups. More time may be needed for personal support to form. The third issue studied was the impact of size of group on self-esteem. Three

aspects of self-esteem were examined: social, competence, and academic selfestee m. The results indicated that there were no significant differences among

270 The Journal of General Psychology conditions for competence and academic self-esteem. In regard to social selfeste em, participants working in cooperative pairs had higher self-esteem than participan ts in the individualistic and groups of four conditions. It seems that social self-esteem (i.e., a self-image of being effective and skilful in social relatio nships) responded more to a single relationship than from having three groupmates (which provided more opportunity to communicate, provide leadership, and exert influenc e). Perhaps the complexity of working in a group of four may have caused participants to feel somewhat inept socially. Working with a partner seems to ha ve a powerful effect on social self-esteem. More is not necessarily better when it comes to social self-esteem. The results of this study provide important implications for social interdepende nce theory. One of the mediating conditions between cooperation and achievement is competence in interpersonal and small group skills (Johnson & R. Johnson, 2005; Johnson & R. T. Johnson, 1989). As it is more complex to coordina te efforts in large than in small groups, it seems that size of group does affect t he outcomes of cooperative efforts, at least initially. Until group members develop the skills and perfect the procedures needed to coordinate and organize the effo rts of group members, the full potential of cooperation may not be used. In addition , there are few studies that have used task interdependence as the operationalizat ion of cooperation. This study provides evidence that task interdependence is effect ive in creating cooperation among participants. Besides having theoretical relevance, the results of this study have practical implications for the use of cooperative learning. When teachers are using cooper ative learning with inexperienced or unskilled participants, they may wish to begin with pairs. In this study, pairs signficantly outperformed groups of four on the first test. Working in pairs seems to be simpler than working in groups of f our. Once participants master the skills and procedures needed to coordinate efforts, the size of the group may not matter. When teachers wish to promote academic social support among participants, whether the group size is two or four does no t seem to matter. When teachers wish to promote participant social self-esteem, pairs seem to be advisable. The more personal interaction with one other person

seems to benefit participants

sense of social self-worth.

The results of this study are limited by the nature of the sample, the procedure s used to implement cooperative and individualistic learning, the nature of the instruments used to measure achievement, social support, and self-esteem, and experimental methodology. The findings of this study should be replicated with different populations using a variety of measures. Finally, it should be noted that the findings of any one study must be considered tentative, awaiting furthe r research and replications. In summary, the results of this study indicate that cooperative efforts tend to promote higher achievement than individualistic efforts. This does not mean, however, that all cooperative groups will outperform individuals under all condi tions. It is somewhat of a paradox as resources increase, so do the difficulties

Bertucci, Conte, Johnson, & Johnson 271 in coordinating behavior. The larger the cooperative group, the longer it may ta ke for group members to develop the procedures and skills needed to work together effectively and, therefore, the longer it may be before learning in a cooperativ e group is more effective than learning alone. In addition, increases in group siz e does not mean that academic social support and social self-esteem will also increase; especially when teachers wish to increase social self-esteem, they may wish to keep the size of cooperative groups small. AUTHOR NOTES Andrea Bertucci is a cognitive psychologist. His reaserch interests are cooperative learning, conflict resolution, and research methodology. He received his PhD from the Univ ersity of Cagliari. Stella Conte is a professor of general psychology at the University of Cagliari. Her research interests are cooperative learning, animal behavior, research metho dology, and marketing. She received her doctoral degree in cognitive psychology from La Sapienza University in Rome. David W. Johnson is a professor of educational psychology at the University of Minnesota. He is a codirector of the Cooperative Learning Center. His research interests include cooperation and competition, conflict resolution, and peace ps ychology. He received his master s degree and doctoral degrees in social psychology from Col umbia University. Roger T. Johnson is a professor of education at the University of Minnesota. He is codirector of the Cooperative Learning Center. His research interests include cooperation and competition, conflict resolution, and inquiry learning. He received his doct oral degree from the University of California, Berkeley. REFERENCES Bales, R., & Strodtbeck, F. (1951). Phases in group problem solving. Journal of Abnormal and Social

Psychology, 46, 485 495. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. London: Hogarth. Bracken, B. A. (1992). Multidimensional self concept scale.Austin,TX: PRO-ED. Brislin R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185 216. Cohen, S., & Willis, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypoth esis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310 357. Deutsch, M. (1962). Cooperation and trust: Some theoretical notes. In M.R. Jones (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 275 320. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Fox, D. (1985). Psychology, ideology, utopia, and the commons. American Psychologist, 40, 48 58. Geen, R. (1976). Test anxiety, observation, and range of cue utilization. Britis h Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 15, 253 259. Geen, R. (1980). The effects of being observed on performance. In P. Paulus (Ed. ), Psychology of group influence (pp. 61 97). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Johnson, D. W. (1981). Student-student interaction: The neglected variable in ed ucation. Educational Researcher, 10, 5 10. Johnson, D. W. (2009). Reaching out: Interpersonal effectiveness and self-actualization (10th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. (2009). Joining together: Group theory

and group skills (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1996). Meaningful and manageable assessment through cooperative learning. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

272 The Journal of General Psychology Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (2005). New developments in social interdependence theory. Psychology Monographs, 131(4), 285 358. Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1983). Social interdependence and perceived ac ademic and personal support in the classroom. Journal of Social Psychology, 120, 77 82. Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and competition. theory and research. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T. & Anderson, D. (1983). Social interdependence and classroom climate. Journal of Psychology, 114, 135 142. Kerr, N. (1989). Illusions of efficacy: The effects of group size on perceived e fficacy in social dilemmas. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 287 313. Lew, M., Mesch, D., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1986). Positive interdependen ce, academic and collaborative-skills group contingencies and isolated students. Ame rican Educational Research Journal, 23, 476 488.

Morgan, B., Coates, G., & Rebbin, T. (1970). The effects of Phlebotomus fever on sustained performance and muscular output (Tech. Rep. No. ITR-70-14). Louisville, KY: University of Louisville, Performance Research Laboratory. Murphy, L. L., Impara, J. C., & Plake, B. S. (Eds.). (1999). Tests in print V. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ortiz, A., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1996). The effect of positive goal and resource interdependence on individual performance. Journal of Social Psychology, 136(2), 243 249. Sarason, I., Levine, H., Basham, R., & Sarason, B. (1983). Assessing social supp ort: The social support questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 127 139. Sarason, I., Sarason, B., & Linder, K. (1983). Assessed and experimentally provided social support. Technical Report, Seattle: University of Washington. Seta, J. J., Paulus, P. B., & Schkade, J. K. (1976). Effects of group size and p

roximity under cooperative and competitive conditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(1), 47 53. Stephan, F., & Mishler, E. (1952). The distribution of participation in small gr oups: An exponential approximation. American Sociological Review, 17, 598 608. Thor, E. (1976). The function of group size and ability level on solving a multi dimensional complementary task. Journal f Personality and Social Psychology, 34(5), 805 808. Wallston, B., Alagna, S., DeVellis, B., & DeVellis, R. (1983). Social support an d physical health. Health Psychology, 2, 367 391. Watson, G., & Johnson, D. W. (1972). Social psychology: Issues and insights. Philadelphia: Lippincott. Webb, N., & Farivar, S. (1994). Promoting helping behavior in cooperative small groups in middle school mathematics. American Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 369 395. Wechsler, D. (1997). WISC-R: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children (V. di Rubini, E. Padovani, & F. Firenze, Trans.). OS, Organizational Specialist. Wegerif, R., Mercer, N., & Dawes, L. (1999). From social interaction to individu al reasoning: An empirical investigation of a possible sociocultural model of cognitive develo pment. Learning and Instruction, 9, 493 516.

Original manuscript received October 20, 2009 Final version accepted January 6, 2010

Copyright of Journal of General Psychology is the property of Taylor & Francis L td. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyrigh t holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Copyright of Journal of General Psychology is the property of Taylor & Francis L td. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyrigh t holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Literature ReviewДокумент11 страницLiterature Reviewkaleemmib80% (10)

- Scientific Evidence For ReincarnationДокумент2 страницыScientific Evidence For ReincarnationS.r. SarathОценок пока нет

- Resume - Sheetal Khandelwal 2yr Exp TGT - Maths and ScienceДокумент4 страницыResume - Sheetal Khandelwal 2yr Exp TGT - Maths and Sciencekamal khandelwalОценок пока нет

- Lesson 1Документ2 страницыLesson 1api-299789918Оценок пока нет

- Topic: Critical Incident Technique: Presenter: Asma ZiaДокумент25 страницTopic: Critical Incident Technique: Presenter: Asma Ziazia shaikhОценок пока нет

- Discuss Gender Bias in PsychologyДокумент2 страницыDiscuss Gender Bias in PsychologyNaciima Hassan100% (1)

- Values S3Документ5 страницValues S3Alice KrodeОценок пока нет

- Section 2 - WeeblyДокумент13 страницSection 2 - Weeblyapi-469406995Оценок пока нет

- CommunicationДокумент92 страницыCommunicationAnaida KhanОценок пока нет

- Does Dancehall Music Have A Negative Impact On The YouthsДокумент2 страницыDoes Dancehall Music Have A Negative Impact On The YouthsDanielle Daddysgirl WhiteОценок пока нет

- It's Good To Blow Your Top: Women's Magazines and A Discourse of Discontent 1945-1965 PDFДокумент34 страницыIt's Good To Blow Your Top: Women's Magazines and A Discourse of Discontent 1945-1965 PDFRenge YangtzОценок пока нет

- NCM 102NTheories in Health EducationДокумент51 страницаNCM 102NTheories in Health EducationBernadette VillacampaОценок пока нет

- Brief Symptom Inventory: Personality Studies - Study: ValidityДокумент7 страницBrief Symptom Inventory: Personality Studies - Study: ValidityKeen ZeahОценок пока нет

- Information Processing Psychology Write UpДокумент4 страницыInformation Processing Psychology Write UpJess VillacortaОценок пока нет

- Introduction To EntrepreneurshipДокумент15 страницIntroduction To Entrepreneurshipwilda anabiaОценок пока нет

- PPST Ipcrf Mt1-IvДокумент10 страницPPST Ipcrf Mt1-IvShemuel ErmeoОценок пока нет

- John Gottman The Relationship Cure PDFДокумент3 страницыJohn Gottman The Relationship Cure PDFDaniel10% (10)

- Social Work - InterviewДокумент2 страницыSocial Work - InterviewJoyce BaldicantosОценок пока нет

- Civic Lesson Y2 RespectДокумент1 страницаCivic Lesson Y2 RespectLogiswari KrishnanОценок пока нет

- 25 Key Slave RulesДокумент2 страницы25 Key Slave RulesBritny Smith50% (2)

- Byham DDI TargetedSelectionДокумент22 страницыByham DDI TargetedSelectionJACOB ODUORОценок пока нет

- Health EducationДокумент29 страницHealth EducationLakshmy Raveendran100% (1)

- Addis - Mental Time Travel - (2020)Документ27 страницAddis - Mental Time Travel - (2020)M KamОценок пока нет

- The Example of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai: How To Watch A Hindi FilmДокумент4 страницыThe Example of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai: How To Watch A Hindi FilmSameer JoshiОценок пока нет

- The Artist Is PresentДокумент10 страницThe Artist Is Presentsancho108Оценок пока нет

- Chandra Man I NewДокумент2 страницыChandra Man I NewChandramani SinghОценок пока нет

- Psychological Testing - PPT (Joshua Pastoral & Camille Organis)Документ15 страницPsychological Testing - PPT (Joshua Pastoral & Camille Organis)Allysa Marie BorladoОценок пока нет

- Hildegard Peplau's Interpersonal Relations TheoryДокумент8 страницHildegard Peplau's Interpersonal Relations TheoryLord Pozak Miller100% (2)

- Cogat 7 Sample Test PDFДокумент9 страницCogat 7 Sample Test PDFAmir Inayat Malik100% (1)

- Basic 2 Lead Small Teams PDFДокумент46 страницBasic 2 Lead Small Teams PDFMylina FabiОценок пока нет