Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Step-By-Step Diagnostic Approach: History in Pre-Renal Failure

Загружено:

wiggmanИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Step-By-Step Diagnostic Approach: History in Pre-Renal Failure

Загружено:

wiggmanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Step-by-step diagnostic approach

ARF is diagnosed by an acutely rising urea and creatinine. Oliguria or anuria is associated with, but not a requirement for, the diagnosis. General symptoms may include nausea and vomiting. However, the condition is often asymptomatic and only diagnosed by laboratory tests. Uraemia and an altered mental status may occur but these are more commonly seen in advanced ARF and in advanced chronic kidney disease. A history of trauma or underlying disease (e.g., CHF, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and connective tissue diseases such as SLE, scleroderma, and vasculitis) may be present.

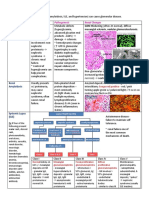

History in pre-renal failure

Patients may have a history of excessive fluid loss from haemorrhage, the GI tract (vomiting, diarrhoea), or sweating. Hospitalised patients may have insufficient replacement fluids to cover ongoing and insensible losses, especially if there is restriction of enteral input. There may be a history of sepsis or pancreatitis. Patients may present with symptoms of hypovolaemia: thirst, dizziness, tachycardia, oliguria, or anuria. Orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea may occur if they have advanced cardiac failure leading to depressed renal perfusion.

History in intrinsic renal disease

The patient may have a history of rash, haematuria, or oedema with HTN suggesting nephritic syndrome and an acute glomerulonephritis or renal vasculitis. They might have had a recent vascular intervention, which may precede ARF due to cholesterol emboli or contrast-induced injury. A history of myeloproliferative disorder such as multiple myeloma may predispose to ARF, particularly in volume-depleted patients. A history of all current medicines and any recent radiological examinations should be taken to establish any exposure to potential nephrotoxins. Allergic interstitial nephritis may be suspected in patients with a history of NSAID use or recent administration of new medicines such as beta-lactam antibiotics. Pigment-induced ARF, due to rhabdomyolysis, should be suspected in patients presenting with muscle tenderness, seizures, drug abuse or alcohol abuse, excessive exercise, or limb ischaemia (e.g., from crush injury). Medicines, including aciclovir, methotrexate, triamterene, indinavir, or sulphonamides, can cause tubular obstruction by forming crystals. Over-the-counter

medications are often overlooked, [43] and patients should be specifically queried about their use.

History in post-renal failure

Post-renal failure is more common in older men with prostatic obstruction. There is a history of urgency, frequency, or hesitancy. A history of malignancy, nephrolithiasis, or previous surgery may coincide with the diagnosis of obstruction. Obstruction caused by renal calculi or papillary necrosis typically presents with flank pain and haematuria.

Physical examination

Hypotension, HTN, pulmonary oedema, or peripheral oedema may be present. There may be asterixis or altered mental status if uraemia is present. The patient with fluid loss, sepsis, or pancreatitis may have hypotension along with other signs of circulatory collapse. Patients with glomerular disease typically present with HTN and oedema, proteinuria, and microscopic haematuria (nephritic syndrome). The presence of rash, petechiae, or ecchymoses may suggest an underlying systemic condition such as vasculitis or glomerulonephritis. Patients with acute tubular necrosis may present after haemorrhage, sepsis, drug overdose, surgery, cardiac arrest, or other conditions with hypotension and prolonged renal ischaemia. An underlying abdominal bruit may support renovascular disease. The patient with prostatic obstruction may present with abdominal distension.

Initial tests

Initial work-up should include basic metabolic profile (including urea and creatinine), ABGs and FBC, urinalysis and culture, urinary eosinophil count, urine chemistries (for fractional excretion of sodium, chloride, and urea), renal ultrasound, CXR, and ECG. CXR may reveal pulmonary oedema or cardiomegaly. ECG may demonstrate arrhythmias if hyperkalaemia is present. Bladder catheterisation is recommended in all cases of ARF, if bladder outlet obstruction cannot be quickly ruled out by ultrasound. It is diagnostic and therapeutic

for bladder neck obstruction in addition to providing an assessment of residual urine and a sample for analysis. Arterial blood gases are measured to confirm metabolic acidosis. A ratio of serum urea to creatinine ratio of 20:1 or higher supports a diagnosis of prerenal azotaemia, but other causes of elevated urea must be ruled out (such as druginduced elevations or GI bleeding). A fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) of <1% supports pre-renal azotaemia but may also be seen in glomerulonephritis, hepatorenal syndrome, and some cases of obstruction, as long as tubular function remains intact. The FENa is calculated as follows: (urine sodium x plasma creatinine)/(plasma sodium x urine creatinine) x 100%. A low fractional excretion of chloride and elevated fractional excretion of urea supports a diagnosis of pre-renal azotaemia. Levels lower than 2% are often seen in acute tubular necrosis (ATN), but are also seen in the presence of diuretic use, whereas levels <1% support a diagnosis of pre-renal azotaemia. The fractional excretion of chloride is calculated as follows: (urine chloride x plasma creatinine)/(plasma chloride x urine creatinine) x 100%. A fractional excretion of urea of <35% supports a diagnosis of pre-renal azotaemia and is used if the patient has had diuretic exposure. The fractional excretion of urea is calculated as follows: (urine urea x plasma creatinine)/(plasma urea x urine creatinine) x 100%. A fluid challenge may be administered with crystalloid or colloid, and is both diagnostic and therapeutic for pre-renal azotaemia if renal function improves. High urine osmolality, seen in pre-renal azotaemia, suggests maintenance of normal tubular function and response to ADH in cases of hypovolaemia. Urine sodium concentration of <20 mmols/L (20 mEq/L) suggests avid sodium retention and would be seen in renal hypoperfusion/pre-renal azotaemia. High urinary sodium is often seen in ATN, but is not exclusive to the diagnosis. Urine osmolality may be very high as the result of radiocontrast dyes and mannitol. Urinary eosinophils of more than 5% to 7% supports, but is not diagnostic for, interstitial nephritis. A renal ultrasound is ordered at onset of work-up to assist in evaluation of postobstructive causes as well as in the evaluation of renal architecture and size. It is also useful for diagnosis of underlying chronic kidney disease.

Subsequent tests

A CT scan may be required to further evaluate cases of obstruction suggested on ultrasound (e.g., possible masses or stones).

Nuclear renal flow scans can evaluate renal perfusion and function, and may be modified using captopril to evaluate for renal artery stenosis, or furosemide to evaluate for obstruction in cases of mild hydronephrosis, where obvious mechanical obstruction is uncertain. Further diagnostic tests may be determined by the suspected cause of ARF, such as cystoscopy for cases of suspected ureteral stenosis or serological evaluation (e.g., anti-streptolysin O, ESR, ANA, anti-DNA, complement, anti-glomerular basement membrane, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, acute hepatitis profile, HIV test, and cryoglobulins) if the history suggests autoimmune, vasculitis, infectious, or immune complex disease, or in cases of suspected glomerulonephritis. Novel serum and urinary biomarkers are showing potential as useful indicators for the diagnosis of acute renal failure and as predictors of mortality after acute renal failure. [44] Further studies are needed. A renal biopsy may be performed for further evaluation of ARF when the history, and physical and other studies suggest systemic disease as aetiology or when the diagnosis is unclear. Biopsies may confirm acute tubular necrosis, but are rarely done for this condition.

Вам также может понравиться

- Diagnostic Pathology of Hematopoietic Disorders of Spleen and LiverОт EverandDiagnostic Pathology of Hematopoietic Disorders of Spleen and LiverОценок пока нет

- Urinary Stones: Medical and Surgical ManagementОт EverandUrinary Stones: Medical and Surgical ManagementMichael GrassoОценок пока нет

- Cirrhosis Alcoholic Liver DiseaseДокумент10 страницCirrhosis Alcoholic Liver DiseaseSarah ZiaОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal Failure in The Hospital: Diagnosis and ManagementДокумент8 страницAcute Renal Failure in The Hospital: Diagnosis and ManagementJulio César Valdivieso AguirreОценок пока нет

- Current Concepts: Cute LiguriaДокумент5 страницCurrent Concepts: Cute Liguriakate blackОценок пока нет

- Usmle World Ed ObjectiveДокумент16 страницUsmle World Ed ObjectiveNisarg Patel100% (3)

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент8 страницAcute Renal FailureRohitKumarОценок пока нет

- Management of End-Stage Liver DiseaseДокумент34 страницыManagement of End-Stage Liver DiseaseAldo IbarraОценок пока нет

- Management: DiagnosisДокумент6 страницManagement: DiagnosisAhmed El-MalkyОценок пока нет

- Acrf CДокумент70 страницAcrf CHussain AzharОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney InjuryДокумент17 страницAcute Kidney InjuryCha-cha UzumakiОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент19 страницAcute Renal FailureUmmul HidayahОценок пока нет

- Metabolic Evaluation: Urine AssessmentДокумент15 страницMetabolic Evaluation: Urine AssessmentKaizer JhapzОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент34 страницыAcute Renal Failureaibaloca67% (9)

- DR - Mugalo E.L.Документ18 страницDR - Mugalo E.L.khadzx100% (2)

- Renal Disease: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)Документ5 страницRenal Disease: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)api-142637023Оценок пока нет

- Essential Update: FDA Approves First Test To Predict AKI in Critically Ill PatientsДокумент5 страницEssential Update: FDA Approves First Test To Predict AKI in Critically Ill PatientsRika Ariyanti SaputriОценок пока нет

- Secondary HypertensionДокумент9 страницSecondary HypertensionGautam JoshОценок пока нет

- Perioperative Care of The Patient With Renal FailureДокумент17 страницPerioperative Care of The Patient With Renal FailureWhempyGawenОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal Failure DXДокумент7 страницAcute Renal Failure DXfarid akbarОценок пока нет

- Done By: Dana Othman: AscitesДокумент28 страницDone By: Dana Othman: Ascitesraed faisalОценок пока нет

- Jasmin O. Dingle BSN-4y1-3CДокумент6 страницJasmin O. Dingle BSN-4y1-3CJasmn DingleОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент14 страницAcute Renal FailureBianca EmanuellaОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент33 страницыAcute Renal FailureAqsa Akbar AliОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal FailureДокумент20 страницAcute Renal Failurewilfridus erikОценок пока нет

- Urology MCQsДокумент13 страницUrology MCQsRahmah Shah Bahai83% (6)

- Acute Renal Failure in The ICU PulmCritДокумент27 страницAcute Renal Failure in The ICU PulmCritchadchimaОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Approach To Chronic Kidney DiseaseДокумент3 страницыDiagnostic Approach To Chronic Kidney DiseaseBlomblom Pow00Оценок пока нет

- Ascites: Phillip S. Ge, MD, Carlos Guarner, MD, PHD, and Bruce A. Runyon, MDДокумент12 страницAscites: Phillip S. Ge, MD, Carlos Guarner, MD, PHD, and Bruce A. Runyon, MDTere DelgadoОценок пока нет

- Coursematerial 136Документ13 страницCoursematerial 136Nyj QuiñoОценок пока нет

- Laporan Kasus TLS (Tumor Lisis Sindrome)Документ58 страницLaporan Kasus TLS (Tumor Lisis Sindrome)Petrus IriantoОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney FailureДокумент2 страницыAcute Kidney FailureKunjan ShahОценок пока нет

- Indications For TransplantДокумент4 страницыIndications For TransplantDorina EfrosОценок пока нет

- Lecture 2. Acute Renal FailureДокумент85 страницLecture 2. Acute Renal FailurePharmswipe KenyaОценок пока нет

- Inter'Medic AKIДокумент48 страницInter'Medic AKIMAHEJS HDОценок пока нет

- Emergencia UrologicaДокумент13 страницEmergencia UrologicaEduardo DV MunizОценок пока нет

- Renal FailureДокумент41 страницаRenal Failure12046Оценок пока нет

- Ascitis PDFДокумент17 страницAscitis PDFLeonardo MagónОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Approach To Patients With Cholestatic Jaundice: ReviewДокумент11 страницDiagnostic Approach To Patients With Cholestatic Jaundice: ReviewdanaogreanuОценок пока нет

- Management of Ascites in Cirrhosis: AdvancesinclinicalpracticeДокумент10 страницManagement of Ascites in Cirrhosis: AdvancesinclinicalpracticeSergiu ManОценок пока нет

- 2019-The Case For Uric Acid-Lowering Treatment in Patient in Patients With Hyperuricemia and CKDДокумент9 страниц2019-The Case For Uric Acid-Lowering Treatment in Patient in Patients With Hyperuricemia and CKDCinantya Meyta SariОценок пока нет

- Dpi Intro Irc Ira TBCДокумент8 страницDpi Intro Irc Ira TBCVictor TullumeОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney InjuryДокумент20 страницAcute Kidney InjuryTishya MukherjeeОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal Failure/ Gagal Ginjal Akut: Tunggul Adi P., M.SC., Apt. Lab Farmasi Klinik, Farmasi, FKIK, UNSOEDДокумент27 страницAcute Renal Failure/ Gagal Ginjal Akut: Tunggul Adi P., M.SC., Apt. Lab Farmasi Klinik, Farmasi, FKIK, UNSOEDPramita Purbandari100% (1)

- Fulminant Hepatic FailureДокумент10 страницFulminant Hepatic FailureAira Anne Tonee VillaminОценок пока нет

- Acute Liver Failure-1Документ40 страницAcute Liver Failure-1elizabethОценок пока нет

- Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Obstruction and Hydroneph PDFДокумент32 страницыClinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Obstruction and Hydroneph PDFAmjad Saud0% (1)

- 6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisДокумент55 страниц6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisAnonymous vUEDx8100% (1)

- Cirrhosis Hours: 5. Working Place: Classroom, Hospital Wards. QuestionsДокумент5 страницCirrhosis Hours: 5. Working Place: Classroom, Hospital Wards. QuestionsNahanОценок пока нет

- Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jan 1 67 (1) :67-74.: January 1, 2003 Table of ContentsДокумент13 страницAm Fam Physician. 2003 Jan 1 67 (1) :67-74.: January 1, 2003 Table of ContentsaanyogiОценок пока нет

- Aetiology: Save Time & Improve Your PDP On Patient - Co.ukДокумент9 страницAetiology: Save Time & Improve Your PDP On Patient - Co.ukBaihaqi SaharunОценок пока нет

- Acute Tubular Necrosis PuputДокумент7 страницAcute Tubular Necrosis Puputganesa ekaОценок пока нет

- 1866-Jepson - ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY EARLY IDENTIFICATION FOR PROMPT MANAGEMENTДокумент3 страницы1866-Jepson - ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY EARLY IDENTIFICATION FOR PROMPT MANAGEMENTYaiza Garcia CasadoОценок пока нет

- Perioperative Oliguria and ATNДокумент22 страницыPerioperative Oliguria and ATNmhelmykhafagaОценок пока нет

- Ascitis ImportanteДокумент17 страницAscitis Importantedanyescalerapumas24Оценок пока нет

- MRCP 2 Nephrology NOTESДокумент74 страницыMRCP 2 Nephrology NOTESMuhammad HaneefОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney Injury & Chronic Kidney Disease: Amir Syahmi Derrick Ezra NGДокумент45 страницAcute Kidney Injury & Chronic Kidney Disease: Amir Syahmi Derrick Ezra NGDerrick Ezra NgОценок пока нет

- AASLD Practice Guidelines For Ascites in CirrhosisДокумент9 страницAASLD Practice Guidelines For Ascites in CirrhosisSalman AlfathОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney Injury: On Completion of This Chapter, The Learner Will Be Able ToДокумент9 страницAcute Kidney Injury: On Completion of This Chapter, The Learner Will Be Able TojhcacbszkjcnОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney InjuryДокумент23 страницыAcute Kidney InjuryBaraka SayoreОценок пока нет

- Surgery PackratДокумент46 страницSurgery PackratRicardo Nelson100% (4)

- NBME 18 AnswersДокумент202 страницыNBME 18 AnswersTony Lǎo Hǔ Chen86% (37)

- Robinson Pathology Chapter 20 KidneyДокумент11 страницRobinson Pathology Chapter 20 KidneyElina Drits100% (1)

- MHD Exam 5 MaterialДокумент122 страницыMHD Exam 5 Materialnaexuis5467100% (1)

- KDIGO AKI Guideline PDFДокумент141 страницаKDIGO AKI Guideline PDFAbigail LucasОценок пока нет

- Prioritization of Nursing Care PlansДокумент10 страницPrioritization of Nursing Care PlansgoyaОценок пока нет

- Renal Notes Step 2ckДокумент34 страницыRenal Notes Step 2cksamreen100% (1)

- NBM18Q&AДокумент11 страницNBM18Q&AIlse Pol TRuizОценок пока нет

- KDIGO AKI Guideline DownloadДокумент141 страницаKDIGO AKI Guideline DownloadSandi AuliaОценок пока нет

- 7 Urinary Disorders - 2012 - Small Animal Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods Fifth EditionДокумент30 страниц7 Urinary Disorders - 2012 - Small Animal Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods Fifth EditionNarvarte Hospital Veterinario de EspecialidadesОценок пока нет

- Renal Osmosis HY Pathology Notes ATF - ATFДокумент109 страницRenal Osmosis HY Pathology Notes ATF - ATFTran Thai Huynh NgocОценок пока нет

- Harrison MCQ NephrologyДокумент7 страницHarrison MCQ Nephrologydrtpk80% (15)

- Approachtoelectrolyte Abnormalities, Prerenal Azotemia, AndfluidbalanceДокумент15 страницApproachtoelectrolyte Abnormalities, Prerenal Azotemia, AndfluidbalanceCecilia GrayebОценок пока нет

- Morena E. Dail, RMT, MT (Amt), Mls (Ascpi) : Mors CodeДокумент53 страницыMorena E. Dail, RMT, MT (Amt), Mls (Ascpi) : Mors CodemeriiОценок пока нет

- Week 7. Renal Pathology Continued.Документ9 страницWeek 7. Renal Pathology Continued.Amber LeJeuneОценок пока нет

- Exam #4 - Urinary and Renal-1Документ14 страницExam #4 - Urinary and Renal-1aerislina100% (6)

- The Hepatorenal Syndrome: 11 Pathophysiology and Treatment Ofascites andДокумент27 страницThe Hepatorenal Syndrome: 11 Pathophysiology and Treatment Ofascites andJose JulcaОценок пока нет

- CRFДокумент50 страницCRFKevin MontoyaОценок пока нет

- Notes On Renal Function Tests by Dr. Ashish Jawarkar ContactДокумент26 страницNotes On Renal Function Tests by Dr. Ashish Jawarkar ContactChaht RojborwonwitayaОценок пока нет

- Acute Kidney InjuryДокумент8 страницAcute Kidney InjuryRohitKumarОценок пока нет

- Clinical Chemistry Lecture NPNДокумент5 страницClinical Chemistry Lecture NPNmizunoОценок пока нет

- Clinical Chemistry I Tests TableДокумент4 страницыClinical Chemistry I Tests TableZoe Tagoc100% (3)

- Acute Renal Failure Lecture 1 Critical Care NursingДокумент52 страницыAcute Renal Failure Lecture 1 Critical Care NursingDina Rasmita100% (2)

- 1.2 Cardinal Manifestations of Renal Disease DR MoraДокумент36 страниц1.2 Cardinal Manifestations of Renal Disease DR MoraJewelОценок пока нет

- Acute Renal Failure-Step23C - 1Документ28 страницAcute Renal Failure-Step23C - 1DEBJIT SARKARОценок пока нет

- Renal Pathology Lectures - PPT SeriesДокумент267 страницRenal Pathology Lectures - PPT SeriesMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.100% (12)

- Renal Diseases " Review "Документ22 страницыRenal Diseases " Review "api-3827876Оценок пока нет

- MCQs in Fluid and Electrolyte Balance With AnswersДокумент50 страницMCQs in Fluid and Electrolyte Balance With AnswersAbdulkadir Waliyy Musa100% (2)

- Article 1 PDFДокумент4 страницыArticle 1 PDFSally TareqОценок пока нет

- Chronic Renal Failure in Horses PDFДокумент20 страницChronic Renal Failure in Horses PDFMarcela SolarteОценок пока нет