Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Parenting Styles

Загружено:

Amanda MaraisИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Parenting Styles

Загружено:

Amanda MaraisАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Parenting styles By Amanda Marais Educational Psychologist amanda@sa-sky.co.

za

It has been shown that parents have a tendency to interact consistently with all their children over time (Eisenberg, Hofer, Spinrad, Gershoff, Valiente, Losoya, Zhou, Cumberland, Liew, Reiser and Maxon (2008:1-160). The observed stability in parenting has led to the identification of different parenting styles used by parents.

Three parenting styles were originally identified by Diana Baumrind (1971:1103): the authoritative (democratic) style, the authoritarian style and the permissive style. A fourth type, the uninvolved or neglecting style, has been identified by other researchers (Lee, Daniels and Kissinger 2006:253-259). A closer examination of parenting revealed two dimensions of parenting behaviours, demandingness and responsiveness (Diana Baumrind 1971:1103).

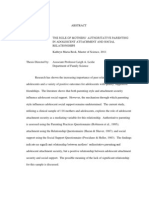

The extent to which parents demand that their child complies with certain standards is referred to as the level of demandingness in the relationship. The second dimension is responsiveness. Some parents are accepting of and responsive to their children. Parents who are very responsive, demand very little and rarely try to influence their childs behaviour (Berk 2000:563). 2.3 Parenting styles can be classified according to the extent that the style is demanding or responsive. The following diagram, based on Berks (2000:563) illustration, shows the four different parenting styles as they differ on these dimensions.

RESPONSIVE

DEMANDING

Democratic /Authoritative

Permissive

Authoritarian

Uninvolved

UNRESPONSIVE

It is generally accepted that the democratic style is the preferred style for raising children because it leads to favourable outcomes, not only for adolescents development, but also for the parent-adolescent relationship (Berk 2009:569; Garg, Levin, Urajnik and Kauppi 2005:653-661; Steinberg 2001:1-19). The democratic parent is demanding, but warm and responsive to his child (Baumrind 1971:1-103). According to Baumrind (1971:1-103), democratic parents direct the childs activities and explain the reasons for their actions.

Adolescents from democratic families are self-reliant, self-controlled, explorative and content (Baumrind 1971:1-103) and are unlikely to show externalising behaviours, or psychopathology such as anxiety disorders, depression and identity disorders (Castrucci & Gerlach 2006:217-224; Herman, Dornbusch, Herron and Herting 1997:34-67; Dwairy and Menshar 2006:103-117). In addition, the democratic approach decreases the likelihood that adolescents will experience negative social experiences, such as witnessing crime or experiencing peer provocation, for example teasing (Mazefsky and Farrell 2005:71-85). Protection from exposure to aggression in turn leads to lower levels of aggression in adolescents (Mazefsky and Farrell 2005:71-85).

UNDEMANDING

The benefits of the democratic approach for the parent-child relationship, are evident in adolescents reports of positive parent involvement, for example higher levels of parent concern, family discussion and family cohesiveness, compared to adolescent reports of other parenting styles (Garg, Levin, Urajnik and Kauppi 2005:653-661). Further, the democratic approach is associated with adolescents responsiveness to advice from their parents about decisions (Fallon & Bowles 1998:599-608; Mackey, Arnold and Pratt 2001:243-268).

Many researchers have put forward reasons for the substantial and farreaching benefits of the democratic approach. Some authors suggest that control that appears fair and reasonable to the child, not arbitrary, is far more likely to be complied with and internalised (Berk 2009:572). In addition, nurturant parents who are secure in the standards they hold for their children provide models of caring concern as well as confident, self-controlled behaviour (Berk 2009:572). Furthermore, observation of self-confident, rational parental role models, as well as parental expectations that are consistent with childrens abilities, may be reasons why democratic parenting is associated with adolescent emotional self-regulation, high self-esteem, intrinsic motivation, a sense of self-efficacy, independent problem solving, and high levels of cognitive and social development (Aunola, Stattin and Nurmi 2000:205-222; Berk 2000:563-564; Berk 2009:573).

Parents who use an authoritarian parenting style are also demanding, but they try to shape, control and judge the behaviour and attitudes of the child in accordance with a set standard of conduct (Baumrind 1971:1-103). They value obedience as a virtue and use punishment when the childs actions or beliefs conflict with what they think is correct conduct (Berk 2000:564).

Authoritarian parents, that is parents who are detached and controlling, and less warm than other parents, have children who are more discontent, withdrawn, and distrustful than children from democratic families (Baumrind 1971:1-103). Authoritarian parenting is associated with a poor self-concept, external locus of control, low levels of self-efficacy and passive behaviour in adolescents (Aunola, Stattin and Nurmi (2000:205-222; Ingoldsby,

Schvaneveldt, Supple & Bush 2003:139-159; Lee, Daniels and Kissinger 2006:253-259). Adolescents who are passive, have an external locus of control and low levels of self-efficacy, may allow others, for example peers, to influence them (Bester & Fourie 2006:157-169; Isaksen & Roper 2008:10631087). In turn, peer influence can lead adolescents to place pressure on parents to sanction decisions and behaviour that are inconsistent with parental goals.

The authoritarian parenting style is associated with aggression in adolescents (Eldeleklioglu 2007:975-986) and abusive behaviour against parents (Cottrell & Monk 2004:1072-1095). The adolescent need for autonomy causes a reaction from parents aimed at maintaining the same level of rigid control they exercised when the child was younger. As this struggle intensifies, these adolescents use abusive behaviour in an effort to obtain a sense of power in their lives (Cottrell & Monk 2004:1072-1095).

The authoritarian parenting style is associated with psychopathology in both the parent and the child. Anxious parents are likely to use the authoritarian parenting style (Lindhout, Markus, Hoogendijk, Borst, Maingay, Spinhoven, van Dyck & Boer 2006:89-102). They have a less nurturing and more restrictive rearing style, than parents who have lower levels of anxiety. Mental health problems in parents often result in adolescents assuming a caretaker role. Taking on the responsibility for parents wellbeing can lead to resentment towards parents and increased conflict with them over a need for autonomy (Cottrell & Monk 2004:1072-1095; Laurent & Derry 1999:21-26). Parents of children with attention control disorders use the authoritarian style, probably because they are more likely to be directive, and to demand more compliance, in order to encourage socially acceptable behaviour in their highly active, impulsive children (Finzi-Dottan, Manor & Tyano 2006:103-114).

The uninvolved parenting style combines undemanding with unresponsive, rejecting behaviour (Baumrind 1971:1-103). Uninvolved parents show little commitment to caregiving, beyond the minimum effort required to feed and clothe the child. Often they are emotionally detached and depressed, and so overwhelmed by the many stresses in their lives that they have little time and

energy to spare for children. As a result, they may respond to the childs demands for easily accessible items, but do not establish rules and routines aimed at long-term goals for the childs development (Berk 2009:571). At its extreme, uninvolved parenting is a form of child maltreatment called neglect (Berk 2009:571).

The uninvolved parenting style can disrupt virtually all aspects of development, including attachment and cognition, as well as emotional and social development (Berk 2009:571; Steinberg, Blatt-Eisengart & Cauffman 2006:47-58). Adolescents whose parents rarely interact with them and do not monitor their whereabouts show poor emotional self-regulation (Berk 2009:571), are prone to develop anxiety disorders (Hale, Engels & Meeus 2006:407-417), and are often involved in drug use and delinquency (Berk 2009:571). Parents who reject their children may become targets of violence by them (Wells 1987:125-133). The hatred which is accumulated during childhood is then later expressed through either threats or reprisals (Laurent & Derry 1999:21-26).

Parents who use a permissive parenting style, are responsive, nurturant and accepting, but avoid making demands or imposing controls of any kind (Baumrind 1971:1-103). Permissive parents allow children to make many of their own decisions at an age when they are not yet capable of doing so. They can eat meals and go to bed when they feel like it and watch as much television as they want. They do not have to learn good manners or do any household chores. Although some permissive parents truly believe that this approach is best, many others lack confidence in their ability to influence their childs behaviour, and are disorganised and ineffective in running their households (Berk 2000:564).

Parents who are noncontrolling, nondemanding and relatively warm, have children who are overly dependent, more anxious, less inclined to explore, and less self-controlled than children from democratic or authoritarian families (Baumrind 1971:1-103; Steinberg, Blatt-Eisengart & Cauffman 2006:47-58). Furthermore, a permissive parenting style is associated with abusive behaviour

from adolescents towards their parents because it often leads to a parent-child power reversal (Cottrell & Monk 2004:1072-1095, Laurent & Derry 1999:2126). Adolescents who have too much freedom and choice, learn to disregard their parents viewpoints and take total control of their own lives.

Eldeleklioglu (2007:975-986) describes a parenting style called an overprotective parenting style. The researcher is of the opinion that the overprotective attitude of parents is similar to the authoritarian parenting style, in that the parent restricts the adolescents behaviours and shows his love conditionally. Therefore, like the authoritarian family environment, the protective family environment is controlling and restrictive. An overprotective parenting style predicts aggression in adolescents (Eldeleklioglu 2007:975986). Overprotective parents fulfil their childrens smallest desires and carry out any actions that require effort from their children and every behaviour which could evoke frustration is avoided (Laurent & Derry 1999:21-26). Such parenting can lead to an escalation of the childs demands on parents and the child can develop tyrannical behaviours. In this context, the violence that these children perpetrate can also be considered a search for autonomy (Cottrell & Monk 2004:1072-1095; Laurent & Derry 1999:21-26).

Aggressive adolescents perceive that the rewards of their negative behaviours outweigh the consequences (Baron & Byrne 1994:439). Over time, a pattern forms in which adolescents learn that their intimidating tactics can be used as a successful means of coercing parents into compliance. In other words, parents may be permissive in order to avoid conflict with their adolescent children.

Another parenting style may be identified which is similar to the permissive style in that it is characterised by high levels of responsiveness, and low levels of demandingness. However, the parenting style is not determined by the parents, but rather develops because adolescent children pressurise their parents to behave in certain ways. Baumrind (1971:1-103) alludes to this type of interaction when she describes some permissive parents as those who are unable to enforce their directives, and who avoid open confrontation with their

children. In addition, Berk (2000:564) has noted that some permissive parents lack confidence in their ability to influence their childs behaviour. Further, it has been observed by many high school teachers, that some parents are aware that their adolescent is involved in delinquent acts, such as smoking or drinking alcohol, but are afraid to confront their child. Therefore, it may be that some permissive parents experience fear of their adolescent children, and are afraid to set limits on their behaviour. An additional parenting style may therefore be identified, one that is determined by the adolescent. In this parenting style the adolescent pressurises his parents in such a way that they avoid open confrontation. Parents are unable to enforce their directives, lack confidence in their ability to influence their childs behaviour, and may be afraid of their adolescent children (Eldeleklioglu 2007:975-986). Such a parenting style may be identified as a forced permissive parenting style.

Вам также может понравиться

- Parenting Styles Influence on Children's BehaviorДокумент13 страницParenting Styles Influence on Children's BehaviorJessa Elegino Bustamante100% (1)

- Baumrind's Parenting Style and Maccoby & Martin's Parenting Style TypologiesДокумент14 страницBaumrind's Parenting Style and Maccoby & Martin's Parenting Style TypologiesKathy Vilcherrez Pizarro100% (30)

- Parental Influence on Gender RolesДокумент6 страницParental Influence on Gender RolesDaka DobranićОценок пока нет

- Four Parenting Styles and Their ImpactДокумент3 страницыFour Parenting Styles and Their Impactselvyw_1100% (2)

- Perceived Parenting Styles and Social SuДокумент48 страницPerceived Parenting Styles and Social SuRodel Ramos DaquioagОценок пока нет

- Baumrind Parenting StylesДокумент1 страницаBaumrind Parenting StylesJ Iván Fernández100% (2)

- Parenting Style, Attachment Style, and Social SupportДокумент67 страницParenting Style, Attachment Style, and Social SupportAlexandra CabreraОценок пока нет

- Parenting Style DifferencesДокумент111 страницParenting Style Differencespetros_belachew75% (4)

- Parenting StylesДокумент21 страницаParenting StylesmoonhchoiОценок пока нет

- Parenting Style Impacts Child Self-RegulationДокумент30 страницParenting Style Impacts Child Self-RegulationningruanantaОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Parenting Styles of Primary Caregiver On Emotional Intelligence and Resilience of Adolescents in MumbaiДокумент54 страницыThe Impact of Parenting Styles of Primary Caregiver On Emotional Intelligence and Resilience of Adolescents in MumbaiRajshree FariaОценок пока нет

- Helping siblings get alongДокумент3 страницыHelping siblings get alongbernardОценок пока нет

- Child's Development PDFДокумент12 страницChild's Development PDFAndreea ZahaОценок пока нет

- Parenting StyleДокумент61 страницаParenting StyleNorhamidah AyunanОценок пока нет

- Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Practices: Development of A New MeasureДокумент12 страницAuthoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Practices: Development of A New MeasureAlexandra LazărОценок пока нет

- Parental Authority and Its Effects On The Aggression of ChildrenДокумент6 страницParental Authority and Its Effects On The Aggression of ChildrenapjeasОценок пока нет

- Discipline Is Not A Dirty Word PDFДокумент51 страницаDiscipline Is Not A Dirty Word PDFPrincess IsraelОценок пока нет

- ARENDELL, T. Co-Parenting - A Review of LiteratureДокумент60 страницARENDELL, T. Co-Parenting - A Review of LiteratureJoão Horr100% (1)

- Study - Children With Intellectual DisabilitiesДокумент134 страницыStudy - Children With Intellectual DisabilitiesClaire Wyatt100% (2)

- Early Childhood DevelopmentДокумент2 страницыEarly Childhood Developmentapi-262346997Оценок пока нет

- The 4 Parenting StylesДокумент4 страницыThe 4 Parenting StylesJeff Moon100% (3)

- Parenting Style InventoryДокумент8 страницParenting Style Inventoryvinsynth100% (1)

- Parenting Styles in Relation To Self-Esteem and SCДокумент37 страницParenting Styles in Relation To Self-Esteem and SCKaiser04Оценок пока нет

- Gender Differences in The Relationships Among Parenting Styles and College Student Mental HealthДокумент7 страницGender Differences in The Relationships Among Parenting Styles and College Student Mental HealthghostlatОценок пока нет

- Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale Bers 2Документ2 страницыBehavioral and Emotional Rating Scale Bers 2api-4911621110% (2)

- Speech Outline SamplelДокумент4 страницыSpeech Outline SamplelAna Karina AuadОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Parenting Styles On Personality: A Review of LiteratureДокумент5 страницThe Effect of Parenting Styles On Personality: A Review of LiteratureIJAR JOURNALОценок пока нет

- Child ObservationДокумент6 страницChild Observationatubbs76100% (1)

- Diana Baumrind Defined Four Types of Parenting Styles Through Her StudiesДокумент5 страницDiana Baumrind Defined Four Types of Parenting Styles Through Her StudiesgeneraseanОценок пока нет

- Parenting Styles and It's Correlation To The Academic Performance of The StudentsДокумент66 страницParenting Styles and It's Correlation To The Academic Performance of The StudentsARMY RM IKONIC YUNHYEONG100% (3)

- Selected Developmental Screening Tools A Resource For Early EducatorsДокумент60 страницSelected Developmental Screening Tools A Resource For Early EducatorsEva Sala RenauОценок пока нет

- Effects of Parenting Style On Children DevelopmentДокумент22 страницыEffects of Parenting Style On Children DevelopmentVasiliki Kalyva50% (2)

- The Influence of Parental Behaviour On Adolescent's Emotional Development in The Bamenda II Sub-Division of The North West Region of CameroonДокумент9 страницThe Influence of Parental Behaviour On Adolescent's Emotional Development in The Bamenda II Sub-Division of The North West Region of CameroonEditor IJTSRDОценок пока нет

- Shared Parenting: A Guide For Parents Living ApartДокумент23 страницыShared Parenting: A Guide For Parents Living Apartsiul128100% (1)

- Child Responsibility Attributions PDFДокумент38 страницChild Responsibility Attributions PDFisusovabradavicaОценок пока нет

- Parenting Style Assessment PDFДокумент4 страницыParenting Style Assessment PDFAbyssman ManОценок пока нет

- Paq QuestДокумент3 страницыPaq QuestnurmalajamaludinОценок пока нет

- Guidance On Undertaking A Parenting Capacity AssessmentДокумент10 страницGuidance On Undertaking A Parenting Capacity AssessmentJamie MccОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Parenting Styles and Self Esteem Among Secondary School StudentsДокумент6 страницRelationship Between Parenting Styles and Self Esteem Among Secondary School StudentsEditor IJIRMF100% (1)

- Children's Needs Parenting Capacity - 2nd EditionДокумент276 страницChildren's Needs Parenting Capacity - 2nd EditionFrancisco Estrada100% (2)

- Socialization Practices and Child Competence DimensionsДокумент38 страницSocialization Practices and Child Competence Dimensionscalmeida_31100% (1)

- Child Observation ReportДокумент5 страницChild Observation Reportapi-323831182Оценок пока нет

- Family Assessment Part BДокумент9 страницFamily Assessment Part Bapi-546372896100% (1)

- Emotional Autonomy ScaleДокумент12 страницEmotional Autonomy Scalenandha7922100% (3)

- Attachment Styles: REF No: 554-3270 (SA-Jr Approval)Документ3 страницыAttachment Styles: REF No: 554-3270 (SA-Jr Approval)Danial AriffОценок пока нет

- Baumrind Et Al., 2010Документ46 страницBaumrind Et Al., 2010Aundraya MurdoccaОценок пока нет

- Clinical Report Psychological MaltreatmentДокумент10 страницClinical Report Psychological Maltreatmentapi-341212290Оценок пока нет

- Co-Parenting After DivorceДокумент6 страницCo-Parenting After DivorceSam Hasler100% (5)

- Barber, B. K. (1996) - Parental Psychological Control. Revisiting A Neglected Construct. Child Development, 67 (6), 3296-3319 PDFДокумент25 страницBarber, B. K. (1996) - Parental Psychological Control. Revisiting A Neglected Construct. Child Development, 67 (6), 3296-3319 PDFDavid VargasОценок пока нет

- Case Study: Alaina, A Career Counseling Study.Документ11 страницCase Study: Alaina, A Career Counseling Study.Aurora Borealiss0% (1)

- Erik Erickson TheoryДокумент4 страницыErik Erickson TheoryMuhammad Ather Siddiqi100% (1)

- Social Media and Body Image-6Документ7 страницSocial Media and Body Image-6api-537842821Оценок пока нет

- Parenting EcologicaДокумент459 страницParenting EcologicaNeiler OverpowerОценок пока нет

- Validation of Short Form of Alabama Parenting QuestionnaireДокумент17 страницValidation of Short Form of Alabama Parenting QuestionnaireDijuОценок пока нет

- BYI II Tool ReviewДокумент4 страницыBYI II Tool ReviewAhmed Al-FarОценок пока нет

- Attachment Theory: Mother-Infant BondingДокумент3 страницыAttachment Theory: Mother-Infant BondingRessie Joy Catherine Felices100% (2)

- Interventions To Decrease Verbal AggressionДокумент112 страницInterventions To Decrease Verbal Aggressionapi-202351147Оценок пока нет

- The Impact of Parenting Styles On Social-Emotional Development of Pupils: A Correlational StudyДокумент24 страницыThe Impact of Parenting Styles On Social-Emotional Development of Pupils: A Correlational StudyHanna BulaclacОценок пока нет

- Using Problems to Develop Wisdom and CompassionДокумент2 страницыUsing Problems to Develop Wisdom and Compassionali ilker bekarslanОценок пока нет

- Jasteow 1905 The Subconscious (BOOK)Документ572 страницыJasteow 1905 The Subconscious (BOOK)hoorieОценок пока нет

- Seminar On Premarital SexДокумент2 страницыSeminar On Premarital Sexnichtemp1813Оценок пока нет

- Unit Kesehatan Sekolah Sehat Jiwa Uks Haji ProgramДокумент10 страницUnit Kesehatan Sekolah Sehat Jiwa Uks Haji ProgramarhanОценок пока нет

- Ad and IMC Chapter 5 NotesДокумент61 страницаAd and IMC Chapter 5 Notesteagan.f02Оценок пока нет

- Approaches To Industrial Relation PPT Bba Class PresentationДокумент14 страницApproaches To Industrial Relation PPT Bba Class PresentationmayankОценок пока нет

- Symposium BullyingДокумент28 страницSymposium BullyingJackielyn CatallaОценок пока нет

- Character Reference - John BBДокумент3 страницыCharacter Reference - John BBjohn BrightОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 WorksheetДокумент3 страницыChapter 2 WorksheetjessОценок пока нет

- MCGREGOR Group 8 QuintoДокумент45 страницMCGREGOR Group 8 QuintoLalai SharpОценок пока нет

- Writing Your PTSD Stressor StatementДокумент4 страницыWriting Your PTSD Stressor StatementBillLudley5100% (2)

- Engstrom Mirror Case StudyДокумент4 страницыEngstrom Mirror Case StudySai Sujith PoosarlaОценок пока нет

- Juvenile Delinquency and Crime Prevention 4 5 21Документ66 страницJuvenile Delinquency and Crime Prevention 4 5 21Rj Mel King DonggonОценок пока нет

- FPT UNIVERSITY- CAMPUS CAN THO INTERNSHIP EXPERIENCESДокумент4 страницыFPT UNIVERSITY- CAMPUS CAN THO INTERNSHIP EXPERIENCESAnh ThưОценок пока нет

- The French SpidermanДокумент3 страницыThe French SpidermanKEVINОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Lesson 2 Learning Principles On Development, Social, and Individual DifferencesДокумент7 страницChapter 1 Lesson 2 Learning Principles On Development, Social, and Individual Differenceswilmalene toledoОценок пока нет

- Studying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturyДокумент22 страницыStudying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturybobОценок пока нет

- IMPACT OF LOW S-WPS OfficeДокумент7 страницIMPACT OF LOW S-WPS OfficeCharlie BaguioОценок пока нет

- The Assertiveness Inventory Assessment ToolДокумент3 страницыThe Assertiveness Inventory Assessment Toolsimranarora2007Оценок пока нет

- Clements - Learning Theories AnalysisДокумент10 страницClements - Learning Theories Analysisapi-196648808Оценок пока нет

- What is an Emotion? William James AnalysisДокумент19 страницWhat is an Emotion? William James AnalysisGrahmould Haul100% (1)

- A Parent-Report Instrument For Identifying One-Year-Olds Risk TEAДокумент20 страницA Parent-Report Instrument For Identifying One-Year-Olds Risk TEADani Tsu100% (1)

- Piaget&eriksonДокумент23 страницыPiaget&eriksonrayhana hajimОценок пока нет

- Results and Discussions: Fort San Pedro National High School Sto. Rosario ST., Iloilo CityДокумент22 страницыResults and Discussions: Fort San Pedro National High School Sto. Rosario ST., Iloilo CityCrizJohnG.PaclibarОценок пока нет

- Daily Affirmation For Love 365 Days of Love in Thought and ActionДокумент270 страницDaily Affirmation For Love 365 Days of Love in Thought and ActionGabrielaMilas100% (1)

- Reaching Students Through Creative Teaching: Synectics ModelДокумент19 страницReaching Students Through Creative Teaching: Synectics ModelCroco latoz100% (1)

- How Temperament Affects Children and ParentsДокумент6 страницHow Temperament Affects Children and ParentsJúОценок пока нет

- Principles of ManagementДокумент8 страницPrinciples of ManagementAbidullahОценок пока нет

- Lesson 6 - Actions and ConsequencesДокумент8 страницLesson 6 - Actions and ConsequencesJM JarencioОценок пока нет

- The Psychosocial Adjustment To Illness Scale (Pais) : DerogatisДокумент15 страницThe Psychosocial Adjustment To Illness Scale (Pais) : DerogatisM.Fakhrul KurniaОценок пока нет